Abstract

Background

Uveitis is the most common extra‐articular manifestation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and a potentially sight‐threatening condition characterized by intraocular inflammation. Current treatment for JIA‐associated uveitis (JIA‐U) is largely based on physician experience, observational evidence and consensus guidelines, resulting in considerable variations in practice.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors used for treatment of JIA‐U.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Ovid MEDLINE; Embase.com; PubMed; Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS); ClinicalTrials.gov, and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We last searched the electronic databases on 3 February 2022.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing TNF inhibitors with placebo in participants with a diagnosis of JIA and uveitis who were aged 2 to 18 years old.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodology and graded the certainty of the body of evidence for seven outcomes using the GRADE classification.

Main results

We included three RCTs with 134 participants.

One study conducted in the USA randomized participants to etanercept or placebo (N = 12). Two studies, one conducted in the UK (N = 90) and one in France (N = 32), randomized participants to adalimumab or placebo. All studies were at low risk of bias. Initial pooled estimates suggested that TNF‐inhibitors may result in little to no difference on treatment success defined as 0 to trace cells on Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN)‐grading; or two‐step decrease in activity based on SUN grading (estimated risk ratio (RR) 0.66; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.21 to 2.10; 2 studies; 43 participants; low‐certainty evidence) or treatment failure defined as a two‐step increase in activity based on SUN grading (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.01 to 7.15; 1 study; 31 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Further analysis using the individual trial definitions of treatment response and failure suggested a positive treatment effect of TNF inhibitors; a RR of treatment success of 2.60 (95% CI 1.30 to 5.20; 3 studies; 124 participants; low‐certainty evidence), and RR of treatment failure of 0.23 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.50; 3 studies; 133 participants). Almost all the evidence was on adalimumab and the evidence on etanercept was very limited. For secondary outcomes, one study suggests that adalimumab may have little to no effect on risk of recurrence after induction of remission at three months (RR 2.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 20.45; 90 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) and visual acuity, but the evidence is very uncertain; mean difference in longitudinal logMAR score change over six months was ‐0.01 (95% CI –0.06 to 0.03) and ‐0.02 (95% CI –0.07 to 0.03) using the best and worst logMAR measurement, respectively (low‐certainty evidence). Low‐certainty evidence from one study suggested that adalimumab treatment results in reduction of topical steroid doses at six months (hazard ratio 3.58; 95% CI 1.24 to 10.32; 74 participants who took one or more topical steroid per day at baseline). Adverse events, including injection site reactions and infections, were more common in the TNF inhibitor group. Serious adverse events were uncommon.

Authors' conclusions

Adalimumab appears to increase the likelihood of treatment success and decrease the likelihood of treatment failure when compared with placebo. The evidence was less conclusive about a positive treatment effect with etanercept. Adverse events from JIA‐U trials are in keeping with the known side effect profile of TNF inhibitors. Standard validated JIA‐U outcome measures are required to homogenize assessment and to allow for comparison and analysis of multiple datasets.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Adalimumab; Adalimumab/adverse effects; Arthritis, Juvenile; Arthritis, Juvenile/complications; Arthritis, Juvenile/drug therapy; Etanercept; Etanercept/adverse effects; Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors; Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors/adverse effects; Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; Uveitis; Uveitis/drug therapy; Uveitis/etiology

Plain language summary

[Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)‐associated uveitis: how well do tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors work?]

Key messages

Adalimumab appears to be beneficial for the treatment of JIA‐associated uveitis while the evidence is very limited to etanercept. We did not find enough evidence to say whether these medications prevent vision loss; however, the studies may not have been long enough to detect changes in vision. Side‐effects from TNF inhibitors are usually mild, although rare serious side effects can occur.

What is juvenile idiopathic arthritis‐associated uveitis?

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic condition in childhood and causes inflammation of the joints (arthritis). Some people with JIA also develop inflammation of the eye, known as uveitis. If not adequately detected and treated, uveitis can lead to permanent eye damage, visual impairment, or blindness.

How is JIA‐associated uveitis treated?

There are several types of medications for treating JIA‐associated uveitis. A group of medications called tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are among the treatments used for JIA and JIA‐associated uveitis. These treatments target a protein called 'tumor necrosis factor' that causes inflammation. These medications suppress the immune system to reduce inflammation and prevent eye damage.

What did we want to find out?

The main aim of this review was to determine whether TNF‐inhibitors can improve the symptoms of JIA‐associated uveitis and to summarize the possible harms of these treatments.

What did we do?

We searched the medical literature for studies comparing TNF inhibitor to placebo for JIA‐associated uveitis. We summarized the evidence for our pre‐defined outcomes and graded our confidence in the evidence. Given that included studies did not measure or report our pre‐defined outcomes, we additionally summarized the evidence as report by the individual studies

What did we find?

We identified three relevant studies that included 134 participants. Two studies investigated a TNF inhibitor called adalimumab and one study investigated a TNF inhibitor called etanercept. Each study measured the effect of the medications differently from one another, so it was difficult to compare the studies and draw conclusions. Our initial analysis showed no clear difference between TNF inhibitors and placebo with regard to the risk of treatment success or treatment failure. On reviewing outcomes assessed in the individual studies, TNF inhibitors improved the chance of treatment success and reduced the risk of treatment failure when compared with placebo. One study showed that more patients taking adalimumab than placebo were able to reduce the number of eye drops used, suggesting that the adalimumab may have reduced inflammation.

Medication‐related side effects including injection site reactions and infections were generally mild and were more common in the TNF inhibitor group. Serious adverse events were uncommon but were also seen more often in the TNF inhibitor groups. The overall side effects were similar to those commonly seen in the medications in other diseases.

What does it mean?

Our review suggests that adalimumab, one TNF inhibitor, increases the chance of improving ocular symptoms of uveitis and decrease the chance of worsening uveitis when compared with placebo.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

The evidence is current to 3 February 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| TNF inhibitors compared with placebo for participants with JIA‐associated uveitis | |||||||

| Patient or population: Participants with a diagnosis of JIA and uveitis who are aged 2 to 18 years old Settings: University hospitals and tertiary care hospitals Intervention: TNF inhibitors (Etanercept or Adalimumab) Comparison: Placebo | |||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks*1 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||||

| Proportion of participants with success, defined as 0 to trace cells or 2‐step decrease in activity SUN‐grading (range: 0 to 4+, higher score indicates severe condition) at 2 or 6 months | 250 per 1000 | 165 per 1000 (53 to 525) |

RR 0.66 (95%CI 0.21 to 2.10) | 43 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

Post hoc analysis using the individual trial definitions of treatment response shows a RR of treatment success of 2.60 (95% CI 1.30 to 5.20; 3 studies; 124 participants); the effect was in favor of adalimumab over placebo while evidence on etanercept was very limited | |

| Risk of failure defined as 2‐step increase in activity in SUN grading (range: 0 to 4+, higher score indicates severe condition) at 2 or 6 months | 67 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (1 to 477) |

RR 0.31 (95%CI 0.01 to 7.15) | 31 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

Post hoc analysis using the individual trial definitions of treatment failure of 0.23 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.50; 3 studies; 133 participants); the effect was in favor of adalimumab over placebo while evidence on etanercept was very limited | |

| Risk of recurrence and mean time‐to‐recurrence after induction of remission at 2 or 6 months | See comments. | ‐ | ‐ |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2 |

3 months of disease control with a subsequent disease flare (RR 2.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 20.45; 90 participants; SYCAMORE) | ||

| Mean change from baseline in logMAR visual acuity at 6 months*2 | The mean logMAR in the placebo group was 0.05 using the best (the lowest value) logMAR measurement, and 0.07 using the worst (the highest value) logMAR measurement | Mean longitudinal logMAR over 6 months was on average 0.01 logMAR lower (95% CI –0.06 to 0.03) using the best (the lowest value) logMAR measurement, and on average 0.02 lower (95% CI –0.07 to 0.03) using the worst (the highest value) logMAR measurement | ‐ | 90 (1) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

Another study reported median logMAR visual acuity at baseline and month 2 (ADJUVITE) | |

| Mean change from baseline in number of topical or systemic steroids at 6 months*2 | No data on mean change in number of topical or systemic steroids were available. | ‐ | ‐ |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

Hazard ratio for the reduction to zero drops 3.58 (95% CI 1.24 to 10.32; 74 participants) in participants taking one or more drops at baseline (SYCAMORE) | ||

| Frequency and nature of adverse effects | Ocular complications | See comments. | ‐ | 134 (3) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 |

1 cataract, 1 macular oedema, 4 elevated ocular pressure, 1 vision loss and 1 ocular hypertonia in 83 participants intervention arm; 1 vision loss and 1 ocular hypertonia in 51 participants in placebo arm | |

| Infection | No data on antibiotics use. | ‐ | |||||

| Systemic complication | See comments. | ‐ | 122 (2) |

Injection site reaction (rate ratio 9.88; 95% CI 4.69 to 20.78) and gastrointestinal disorders (rate ratio 4.78; 95% CI 2.72 to 8.38) | |||

| Hospitalization, surgical or medical procedures | See comments. | ‐ | 90 (1) |

1 testicular exploration, 1 antiviral prophylaxis in adalimumab arm | |||

|

*1The assumed risk is based on the estimate in the control group. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). *2The estimates is based on the analyses presented in the included study. CI: confidence interval; JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis; logMAR: logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; RR: risk ratio; SUN: standardization of uveitis nomenclature; TNF: tumor necrosis factor | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

1Downgraded two levels for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals.

2Downgraded one level for indirectness of evidence.

Background

Description of the condition

Uveitis is inflammation of the vascular middle layer of the eye that includes the iris, choroid, and retina (Jabs 2005). Pediatric uveitis is a potentially sight‐threatening inflammatory condition; up to 86% of those affected have been reported to develop ocular complications and 35% of cases result in vision loss (Rosenberg 2004; Rothova 1996). The most common systemic association of pediatric uveitis is juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). JIA is the most common childhood chronic inflammatory disease, with a prevalence of 16 to 150 cases per 100,000 population (Prakken 2011). Uveitis is the most common extra‐articular manifestation of JIA and occurs in up to 30% of children with JIA (Clarke 2016). Uveitis is also a cause of high morbidity and long‐term organ damage in JIA (Vastert 2014); it may precede onset of arthritis in 3% to 7% of children with JIA (Sen 2017).

Despite the strong association between JIA and uveitis, the cause of uveitis is not fully understood. Uveitis is diagnosed most frequently in the subtype of JIA with relatively fewer joint involvement. JIA‐uveitis (JIA‐U) is most often a chronic anterior uveitis; patients may be completely asymptomatic, yet have significant inflammation that can lead to permanent ocular damage and loss of vision (Sen 2017). Based on consensus standards, strict screening guidelines for eye examinations among patients with JIA are recommended in order to optimize early detection and treatment of JIA‐U (Angeles‐Han 2019; Constantin 2018).

The first‐line treatment for JIA‐U is topical or systemic glucocorticoids, or both. If inflammation is inadequately controlled after three months of steroids, systemic immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) is initiated. Methotrexate is well established as the first line IMT (Angeles‐Han 2019; Angeles‐Han 2019a; Constantin 2018; Simonini 2013; Smith 2021; Solebo 2020). Most contemporary treatment guidelines recommend tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for patients with inflammatory disease that is refractory to methotrexate. Other commonly used IMT includes azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, leflunomide, calcineurin inhibitors, and interleukin inhibitors (Angeles‐Han 2019; Angeles‐Han 2019a; Constantin 2018; Heiligenhaus 2019; Smith 2021; Solebo 2020).

Description of the intervention

TNF inhibitors have been used as IMT in adults and children with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, including JIA‐U. Four monoclonal anti‐TNF antibodies are commercially available: infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol. Etanercept is the only commercially available anti‐TNF receptor fusion protein.

Adalimumab and golimumab are fully human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibodies. Infliximab is a mouse‐human chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Certolizumab pegol is a pegylated Fab fragment of humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Etanercept is a fusion protein of the Fc region of human IgG1 and human TNF receptor 2. Infliximab is administered intravenously or subcutaneously, whereas the other four TNF inhibitors are administered subcutaneously (Cordero‐Coma 2015).

Adalimumab and etanercept have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in JIA. Adalimumab is the only TNF inhibitor that is FDA‐approved for treatment of non‐infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis in adults and children two years of age and older. (Gerriets 2020).

How the intervention might work

TNF is a pro‐inflammatory cytokine that plays an essential role in the immune system. It acts as a pivotal upstream trigger of an immune cascade that leads to cell activation and trafficking, cytokine and chemokine production, and initiation of apoptotic pathways (Keystone 2010). Although it is a key mediator that maintains homeostasis in the immune system, high systemic levels of TNF lead to vascular decompensation, inflammation, and organ injury (Beutler 1985). Dysregulation of inflammatory pathways triggered by cytokines such as TNF is thought to be the underlying mechanism that results in immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases, including non‐infectious uveitis.

TNF is produced by both immune and non‐immune cells, depending on the nature of the stimulus. It is synthesized as a transmembrane protein that is converted by an enzyme and released as a soluble fraction. Both membrane and soluble forms of TNF are biologically active (Khera 2012). Activities of TNF are mediated through binding to TNF receptors I and II (TNFR1 and TNFR2), which are present in most cells, including pigment epithelial cells of the iris, ciliary body, and retina (Cordero‐Coma 2015; Khera 2010).

Under normal physiologic conditions, TNF is consumed, so it is not detectable in the serum of healthy individuals. Following an inflammatory stimulus, serum levels of TNF can rise significantly, as it is produced in large quantities by activated cells (Cordero‐Coma 2015). TNF levels in both serum and aqueous humor are elevated in individuals with uveitis (Keystone 2010; Santos Lacomba 2001). The levels of TNF correlate with the severity of disease (Khera 2010). Intravitreal injection of TNF can induce uveitis in animal models (Fleisher 1990; Gregory 2013). Persistent elevation of TNF in aqueous humor leads to tissue damage by reactive oxygen species, breakdown of blood ocular barrier, and upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor leading to angiogenesis (Santos Lacomba 2001).

TNF inhibitors neutralize soluble TNF and some additionally can initiate antibody‐dependent and complement‐dependent cytotoxicity through binding to transmembrane TNF‐expressing cells (Horiuchi 2010). In the experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU) model, TNF inhibition leads to reduced cell trafficking into the retina and prevention of tissue destruction (Dick 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

At present, considerable variations exist in how JIA‐U is treated. Due to the relative lack of clinical trials on JIA‐U, treatment for JIA‐U is based on physician experience, observational studies and consensus guidelines. Even among published clinical studies, there is significant heterogeneity around outcome measures of JIA‐U (Mastrangelo 2019). Several consensus statements have been published in Europe and North America based on expert recommendations. The majority of the expert panels were rheumatologists rather than ophthalmologists. In addition, differences are present among suggested standards of care (Angeles‐Han 2019; Angeles‐Han 2019a; Constantin 2018; Heiligenhaus 2019; Smith 2021; Solebo 2020). Despite these limitations, treatment with TNF inhibitors is becoming a mainstay for methotrexate refractory JIA‐U. We aim with this review to evaluate evidence from randomized controlled trials, to explore possible outcome measures that can be easily converted to clinical utility, and to create a framework for reviewing new IMTs.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐inhibitors used for treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis uveitis (JIA‐U).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included trials that enrolled participants with a diagnosis of JIA‐U who were aged 2 to 18 years old.

We also included one study that involved participants aged older than 18 years (number unknown) as well as two participants with idiopathic chronic anterior uveitis (ICAU) (ADJUVITE). We were unable to access data that excluded the patients over 18 years of age or those with ICAU and elected to include all participants in this study. This decision was made on the basis of the small number of patients with ICAU included and our understanding of the similarities between JIA‐U and ICAU with regard to the clinical course and response to treatment (Heiligenhaus 2020).

Types of interventions

Interventions: TNF inhibitors (anti‐TNFs), including:

adalimumab;

etanercept;

infliximab;

golimumab;

certolizumab.

We accepted anti‐TNFs used at any dosing schedule as tested in the included trials. Studies in which participants received co‐interventions such as methotrexate were included provided the co‐interventions were applied similarly in all treatment groups.

Comparison intervention: placebo or background methotrexate without anti‐TNFs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Treatment success or failure at two to six months

-

Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria score for anterior chamber (AC) cell grading (SUN 2005)

Success defined as 0 to trace cells on SUN‐grading; or two‐step decrease in activity based on SUN‐grading

Failure defined as two‐step increase in activity SUN‐grading

As post hoc analyses, we additionally attempted to examine success and failure as defined in individual trials. These definitions are summarized in Appendix 1.

Secondary outcomes

We assessed secondary outcomes and adverse effects at two to six months. For all outcomes, whether longer‐term data were available (i.e. longer than six months), we also analyzed and report them at the longest follow‐up time.

Efficacy

Risk of recurrence and mean time‐to‐recurrence after induction of remission

Mean change from baseline in visual acuity, measured using tools appropriate for age

Mean change from baseline in quality of life (QoL) measures (note that there are no universally accepted vision‐related QoL instruments for children)

Mean change from baseline in Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)

Mean change from baseline in JIA arthritis flare/response measured by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) score

Mean change from baseline in number or change of dosage of topical or systemic steroid medications

Need for periocular steroids.

Adverse effects

Development of ocular complications

Cataracts, band keratopathy, posterior synechiae, macular edema, epiretinal membrane, hypotony, decrease in vision, elevated eye pressure, optic neuritis, scleritis

Infections

Incidence of antibiotic use as a measure of infection

Systemic complications

Blood or lymphatic system disorder (e.g. neutropenia, raised levels of autoantibodies), severe allergic reactions, injection site condition, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory disorders, new inflammatory disease, neoplasia, multiple sclerosis/demyelination

Hospitalization, surgical or medical procedures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the following electronic databases for RCTs. There were no restrictions to language or year of publication. The electronic databases were last searched on 3 February 2022.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (the latest issue) (Appendix 2).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to present) (Appendix 3).

Embase.com (1947 to present) (Appendix 4).

PubMed (1948 to present) (Appendix 5).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (1982 to present) (Appendix 6).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (Appendix 7).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp) (Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We searched the lists of references of included studies for additional trials. We did not search conference abstracts for the purposes of this review, as many eyes and vision conference abstracts were included in Embase, which we searched as part of the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

After removal of duplicates, two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts of all records identified as a result of the searches using Covidence (Covidence). The review authors classified each record as 'relevant,' 'possibly relevant,' or 'not relevant' based on the eligibility criteria; we retrieved the full‐text articles for records considered 'relevant' or 'possibly relevant.' Two review authors then independently evaluated the full‐text articles for inclusion of the study in the review. In case of questions regarding the eligibility of a study, we contacted the study authors to obtain additional information (ADJUVITE; Alexeeva 2018; EUCTR2010‐020423‐51‐DE; Tynjälä 2011). If the authors did not respond within two weeks, we planned to classify the study as 'awaiting classification'. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between two review authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from the full‐text reports from eligible studies, including the following information: study methods, participant characteristics, interventions, outcomes, results, and other information. We collected data in sufficient detail to facilitate the description of the included studies, construct tables and figures, assess risk of bias, and conduct synthesis. We used Covidence for data extraction (Covidence). We attempted to contact study authors to request missing information or for clarification (ADJUVITE; SYCAMORE). When the authors did not respond within two weeks, we proceeded with the available information. In case of any discrepancies in data extraction between review authors, consensus was reached through discussion. We exported the collated data into RevMan Web 2019.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias with the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool, following the guidance in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019b). Discrepancies between review authors were resolved by discussion.

We considered the following domains of bias:

bias arising from the randomization process;

bias due to deviations from intended interventions;

bias due to missing outcome data;

bias in measurement of the outcome;

bias in selection of the reported result.

We followed the recommended algorithms to reach an overall risk of bias assessment for each trial. The overall risk of bias had three categories: 'low risk of bias,' 'high risk of bias,' or 'some concerns.'

Measures of treatment effect

We conducted data analysis using the guidance in Chapter 9 (McKenzie 2019) and Chapter 10 (Deeks 2019) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019a). We estimated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data, such as the primary outcome defined as success or failure. We did not calculate the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs for continuous outcomes for visual acuity, or the standardized mean difference (SMD) for QoL scores due to insufficient data provided. We did not estimate any hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CIs for time‐to‐event data (time‐to‐recurrence) for the same reason. We present the estimates derived from the original analysis in one study (SYCAMORE) when only one study reported the specific outcome. We used the rate ratio to compare the rate of adverse events per person‐year in intervention and control groups.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the study participant. Both eyes of all participants were included in one study (Smith 2005), and 17 (28%) participants in the adalimumab and eight (27%) participants in the placebo group were enrolled bilaterally in another study (SYCAMORE). It was unclear how the study eye was chosen when both eyes were included (e.g. average of eyes and worse eye etc.). In future updates, if both eyes of participants are randomized (to the same or different interventions), we will extract the results that account for correlation between eyes. If the primary studies fail to consider the correlation between two eyes, we will exclude those studies in a sensitivity analysis. If we include multi‐arm studies, we will determine (i) which intervention groups are relevant to this review, (ii) which intervention groups are relevant to the meta‐analysis, and (iii) how the study will be included in the meta‐analysis if more than two groups are relevant. We will refer to Chapter 23 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for guidance regarding including variants on randomized trials (Higgins 2019c).

Dealing with missing data

When desired data were missing (e.g. missing full‐text trial report, missing information regarding study methods, missing summary data for an outcome, or individual participants missing from the summary data), we contacted the authors of the primary trials to request the information of interest. When the study investigators did not respond within two weeks, we proceeded with the available information and assessed the impact of the missing data on the overall interpretation of results. We did not exclude any studies because of missing data. In dealing with missing data, we followed the recommendations in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies by analyzing the study characteristics and risk of bias assessment. We evaluated statistical heterogeneity by assessing overlap of CIs for effect estimates calculated for individual studies and the I2 statistic. As recommended in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019), we used the following thresholds for the interpretation of I2:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not examine the risk of reporting bias by comparing the outcomes defined in the trial protocol or trial registration with those presented in the full‐text publication or report of the study because we only included three studies. In future updates when 10 or more studies are included in an analysis, we will assess small‐study effect, which could be due to reporting bias, using a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

As only three studies were included, we used a fixed‐effect model. In future updates, we will analyze data using a random‐effects model when more than three studies are included. If we are unable to conduct meta‐analysis due to heterogeneity, we will report a narrative or tabulated summary of the data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform a subgroup analysis according to the type of JIA due to lack of data available:

polyarticular;

oligoarticular;

anti‐nuclear antibodies (ANA) status.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not re‐run meta‐analysis by excluding studies at high risk of bias to determine the effect estimate because all three included studies were at low risk of bias.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a summary of findings table to present the main findings of the review, including key information concerning the certainty of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the summary of available data on the main outcomes (e.g. number of participants, studies that measured the main outcome) according to the guidelines in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2019). Two review authors (WR and JJ) independently performed the GRADE assessment to evaluate the certainty of the review findings (GRADEpro GDT). We graded the certainty of evidence as 'high,' 'moderate,' 'low,' or 'very low' based on (i) high risk of bias among included studies, (ii) indirectness of evidence, (iii) unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, (iv) imprecision of results, and (v) high probability of publication bias.

We included the following outcomes in the summary of findings' table.

Proportion of participants with success at three months, as defined by SUN grading

Risk of failure at three months, as defined by SUN grading

Risk of recurrence and mean time‐to‐recurrence after induction of remission

Mean change from baseline in visual acuity, QoL score, ACR score, andJADAS (Choice is hierarchical in this order).

Mean change from baseline in number of topical or systemic steroids

Frequency and nature of adverse effects.

Results

Description of studies

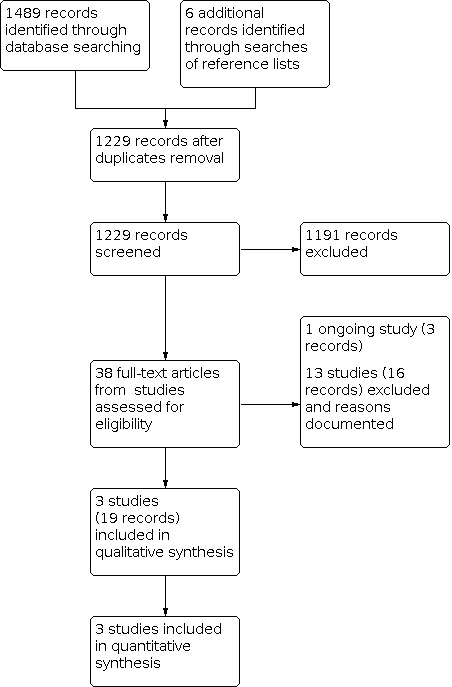

A study selection flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

The electronic databases were searched on 3 February 2022, yielding 1489 records. We additionally found six associated records after we searched the reference lists of included studies. After removing duplicates, we screened 1229 titles and abstracts. Thirty‐eight full‐text reports were retrieved for further review. After full‐text screening, we included three studies (19 records), identified one ongoing study (three records) and excluded 13 studies (16 records) with reasons. We contacted the investigators of four studies to clarify study eligibility. One ongoing study is a multicenter, international randomized controlled trial (RCT) that plans to randomize 118 participants with juvenile idiopathic uveitis (JIA‐U) who are aged two years or older to either continue adalimumab or discontinue adalimumab and receive a placebo (ADJUST). The study started in 2020 and is estimated to complete in 2023.

Included studies

We included three studies with a total of 134 randomized participants. The number of eyes included was unclear because the method of study eye was chosen (e.g. average of two eyes or one eye) was not reported from one study (Smith 2005). Two studies used adalimumab as the investigational medicinal product (ADJUVITE; SYCAMORE), while one used etanercept (Smith 2005). The details of the included studies are shown in Characteristics of included studies.

In one study conducted in France, 32 participants aged four years or older who had chronic, active anterior uveitis associated with JIA or idiopathic (N = 2) and did not respond to previous topical steroid therapy and methotrexate (MTX) were enrolled (ADJUVITE). Participants were randomized to placebo or adalimumab (16 participants in each arm) at a dose of 24 mg/m2 (participants aged less than 13 years) or 40 mg (participants aged 13 years or older). Participants received subcutaneous injections every other week according to their randomized allocations during a double‐blind period of two months, followed by an open‐label period of 10 months during which all participants received adalimumab treatment. The median age of participants was 9.5 years (range 4.9 to 29.1 years), and there were participants aged more than 18 years. The study investigators received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. Another study conducted in the USA enrolled 12 children (mean and median age of 11 years, ranged from 6 to 15 years old) with active uveitis who met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) diagnostic criteria for JIA (Smith 2005). Seven and five participants were randomized to receive either subcutaneous injections of etanercept at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg or placebo, respectively, twice‐weekly during the six‐month masked treatment phase. The third study included 115 eyes of 90 participants (mean age 8.9 ± 3.9 years) with JIA‐associated uveitis were treated and followed in 14 sites in the UK (SYCAMORE). Sixty participants received subcutaneous injection of adalimumab at a dose of 20 mg or 40 mg according to body weight every two weeks, and 30 participants received matching placebo. The trial regimens were continued until treatment failure or 18 months. Authors of this study received non‐financial support from AbbVie Inc. (the Marketing Authorization holder).

The three studies applied the different definitions of treatment success and failure described in Appendix 1. In one study, the primary end point was treatment response at month two, which was defined as a reduction of at least 30% of ocular inflammation quantified by laser flare photometry in the initially more severely inflamed eye without worsening of cell counts or protein flare on slit lamp examination according to Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria (ADJUVITE). In Smith 2005, treatment success was defined as a reduction of anterior chamber cells to 0 or trace using corticosteroid drops less than three times daily, or a 50% reduction in the number of dosage of other anti‐inflammatory medications without an increase in inflammation. The primary endpoint was the time to treatment failure assessed by a multicomponent intraocular inflammation score in SYCAMORE.

Excluded studies

We excluded 13 studies after full‐text review and documented the reasons for exclusion in the "Characteristics of excluded studies" table. In summary, we excluded seven studies due to ineligible study design (i.e. not RCTs), four studies due to the ineligible participants (i.e. adult participants, or not participants with uveitis), and two studies due to the ineligible comparators (i.e. not placebo).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the following domains of risk of bias by using the RoB 2 tool for the primary outcomes (i.e. treatment success or failure).

Bias arising from the randomization process

We judged all three studies as at low risk of bias for this domain. In one study, randomization was performed by using a secure, 24‐hour, web‐based system centrally controlled by the Clinical Trials Research Centre to ensure allocation concealment (SYCAMORE). In another study, participants were randomized at baseline in a 2:1 fashion to receive etanercept or placebo (Smith 2005). Baseline characteristics between intervention groups appeared to be balanced in both studies. One study used a computer‐generated random allocation sequence developed at Paris Descartes Clinical Research Unit (ADJUVITE). Although some baseline characteristics including the proportion of patients with bilateral uveitis or cataract, were unbalanced between intervention groups, imbalance was not likely related to the randomization process, but due to chance as this study had a small sample size (N analyzed = 31, 16 in the treatment group and 15 in the placebo group).

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions

Participants, investigators and study personnel were masked to treatment assignments in SYCAMORE. Participants received identical and prefilled vials in this study. In Smith 2005, clinic staff and study investigators were masked to the study medications for the duration of the study. In the "double‐blind" design, participants and investigators were masked to treatment assignments and blinded injections were applied during the masked phase from day zero to month two (ADJUVITE). Appropriate analyses were performed to estimate the effect of assignment to intervention in all included studies. We judged all three studies as having a low risk of bias for this domain.

Bias due to missing outcome data

Outcome data for the primary end point were available for all, or nearly all participants who underwent randomization. We judged all studies at low risk of bias.

Bias in measurement of the outcome

In ADJUVITE, outcome assessors, first an ophthalmologist and then a pediatrician or a rheumatologist, were masked to each other, but it was unclear whether they were masked to the treatment assignments. We had some concerns for this domain. We judged the remaining two studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain. In Smith 2005, clinic staff and study investigators were masked to the study medication. The outcome assessors were masked to the intervention assignments throughout SYCAMORE. The same methods of measurement, definition, time points were applied for each group.

Bias in selection of the reported result

One study published a protocol and registered the study in a trial registry (SYCAMORE). Although the pre‐specified outcome was modified, the rationale and justification were provided; the primary endpoint was presented using "hazard ratio" for treatment failure because the median time to treatment failure was not reached in the adalimumab group during the planned study period (18 months). Relative risks were also used to compare the overall cumulative incidence of treatment failure in adalimumab versus placebo. The trial registers were publicly available for the remaining studies (ADJUVITE; Smith 2005). These studies were powered to detect differences in success rates, which were the primary efficacy outcomes compared and reported as planned. We judged all three studies as having low risk of bias for this domain.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See:Table 1

Primary outcome

Treatment success at two to six months

Two included studies provided data for treatment success defined as zero to trace cells; or two‐step decrease in activity in SUN‐anterior cell (AC) grading. In one study, two (28.6%) participants in the etanercept arm and two (40%) participants in the placebo arm had AC cell grades of trace or less while receiving topical corticosteroids three times per day at month six (risk ratio (RR) 0.71; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15 to 3.50; 1 study; 12 participants; Analysis 1.1)(Smith 2005). ADJUVITE evaluated response to treatment at the end of a two‐month double‐blind phase. One participant with active arthritis in the placebo arm was withdrawn at day zero without taking any treatment and was excluded from the published analysis. Two (13%) and three (20%) participants were qualified as responders in the adalimumab and the placebo arm, respectively (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.12 to 3.24; 31 participants; Analysis 1.1). A pooled analysis of two studies suggested that TNF inhibitor may have little or no effect on treatment success (RR 0.66; 95%CI 0.21 to 2.10; 43 participants; Analysis 1.1; Figure 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors versus placebo (per review protocol), Outcome 1: Treatment success defined as 0 to trace cells; or 2‐step decrease in activity using in SUN anterior chamber (AC) cell grading

2.

We additionally assessed this outcome using the primary success or response measure as defined by each individual trial. These definitions are summarized in Appendix 1. One group of study investigators used a multicomponent intraocular inflammation score (including a quantified laser flare photometry result) at two months (ADJUVITE). By these methods, they identified 9 of 16 (56%) responders on adalimumab and 3 of 15 (20%) on placebo (RR 2.81; 95% CI 0.94 to 8.45; 31 participants; Analysis 2.1). Another study used a different predefined multicomponent intraocular inflammation score at six months and identified 3 of 7 (43%) of the patients in the etanercept arm and 2 of 5 (40%) in the placebo arm (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.27 to 4.23; 12 participants; Analysis 2.1) as successfully treated (Smith 2005). This outcome closely reflected the SUN definition of response and required a 50% reduction of antiinflammatory medications (Liu 2005). One study reported treatment response at six months but did not clearly define treatment response (SYCAMORE). Twenty of 54 (37%) adalimumab and 3 of 27 (11%) placebo participants responded (RR 3.33; 95% CI 1.09 to 10.24; 81 participants; Analysis 2.1). Nine participants were excluded from the analyses because they had not reached the six‐month time point. Pooled analysis of three studies suggests TNF inhibitor may increase the probability of treatment success (RR 2.60; 95%CI 1.30 to 5.20; 3 studies; 124 participants); most of the evidence available was on adalimumab over placebo (RR 3.11; 95%CI 1.40 to 6.90; 2 studies; 112 participants), while the evidence on etanercept compared with placebo was very limited (RR 1.07: 95%CI 0.27 to 4.23; 1 study; 12 participants)(Analysis 2.1; Figure 3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors versus placebo (per individual study protocol), Outcome 1: Treatment success/response defined by individual study

3.

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading one level due to imprecision of results (−2).

Treatment failure at two to six months

One included study provided data for treatment failure defined as two‐step increase in activity SUN AC grading. In this study, no treatment failures in the adalimumab group and one treatment failure in placebo group were observed at two months (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.01 to 7.15; 1 study; 31 participants; Analysis 1.2) (ADJUVITE).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors versus placebo (per review protocol), Outcome 2: Treatment failure defined as 2‐step increase in SUN anterior chamber (AC) cell grading

We additionally assessed this outcome using treatment failure as defined by each individual trial (Appendix 1). One study used a two‐step increase in activity SUN‐anterior cell (AC) grading as the primary determinant of treatment failure (ADJUVITE). In another study, one participant (20%) in etanercept group and one participant (14%) in placebo group (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.06 to 8.90; 12 participants; Analysis 2.2) experienced treatment failure according to their predefined multicomponent outcome measure (including anterior chamber inflammation, anti‐inflammatory medication doses and development of site threatening ophthalmic lesions) (Smith 2005). In the third study, using a predefined multicomponent intraocular inflammation score (including anterior chamber inflammation, anti‐inflammatory medication doses and poor treatment adherence), 6 of 60 (10%) participants in adalimumab group and 15 of 30 (50%) in the placebo group (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.46; 1 study; 90 participants; Analysis 2.2) had treatment failure at 6 months (SYCAMORE). Pooled analysis of three studies suggests that TNF inhibitor may reduce the risk of treatment failure compared with placebo (RR 0.23, 95%CI 0.11 to 0.50; 133 participants). Most of this evidence regarded adalimumab (RR 0.21; 95%CI 0.09 to 0.47; 2 studies; 121 participants), whereas the evidence on etanercept was very limited (RR 0.71, 95%CI 0.06 to 8.90; 12 participants)(Analysis 2.2; Figure 4).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors versus placebo (per individual study protocol), Outcome 2: Treatment failure/flare defined by individual study

4.

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results.

Secondary outcomes

Risk of recurrence and mean time‐to‐recurrence after induction of remission

No included study examined time to recurrence, but one study provided the data on number of participants having disease flares (as defined by worsening on standardized uveitis nomenclature criteria) following three months of disease control (SYCAMORE). One of the 30 participants in the placebo group (3%) and 5 of the 60 participants in the adalimumab group (8%) experienced three months of disease control with a subsequent disease flare; adalimumab had no effect on this outcome (RR 2.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 20.45).

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as very low, downgrading two levels for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (−2) and one level for indirectness (−1).

Mean change from baseline in visual acuity, measured using tools appropriate for age.

One included study with 90 participants reported the data on change in visual acuity (SYCAMORE). The authors performed two analyses; the data were analyzed either using the best (the lowest value) logMAR measurement (analysis 1) or the worst (the highest value) logMAR measurement (analysis 2) when two eyes were involved. When one eye was involved, the single logMAR result was used. Joint modeling suggested that the treatment effects of adalimumab on the longitudinal logMAR change score over six months were –0.01 (95% CI –0.06 to 0.03) (analysis 1) and –0.02 (95% CI –0.07 to 0.03) (analysis 2), implying that there was no important difference between the treatments, that is one letter or less. These estimates were adjusted for failure because of treatment dropout from the trial. Inferences remained similar following sensitivity analyses. In another study, median logMAR visual acuity was 0.1 (range −0.2 to 1.3) in the adalimumab arm (N = 16) and 0.0 (range −0.2 to 1.0) in the placebo group (N = 15) at baseline, and 0.15 (range −0.10 to 1.10) in the adalimumab arm (N = 16) and 0.00 (range −0.10 to 0.60) in the placebo group ( N =15) at month two (ADJUVITE).

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results (−2).

Mean change from baseline in quality of life (QoL) measures

One included study presented the data on QoL measures by using the Childhood Health Questionnaire psychosocial subscale (CHQ PsS; scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better or more positive health states) and Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ; scores range from 0 to 3, with lower scores indicating better outcomes) (masked and open‐label phases) (SYCAMORE). The authors reported that the estimated treatment effects on longitudinal CHQ PsS and CHAQ scores were 2.69 (95% CI –0.26 to 5.86) and –0.14 (95% CI –0.32 to 0.01), respectively. The confidence intervals were consistent with no evidence of difference between the two interventions.

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals (−2).

Mean change from baseline in Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)

One included study examined the JADAS (SYCAMORE). Most participants entered the study with minimal arthritis and JADAS values were only minimally affected. Longitudinal treatment effects over six months for JADAS 10, 27 and 71 scores were ‐0.35 (95% CI ‐0.79 to ‐0.005), ‐0.34 (95% CI ‐0.78 to 0.03) and ‐0.36 (95% CI ‐0.80 to ‐0.0004), respectively.

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results (−2).

Mean change from baseline in JIA arthritis flare/response measured by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) score

One included study reported ACR pediatric scores (ACR pedi) (SYCAMORE). An ACR Pedi 30 response is defined as at least a 30% improvement from baseline in three of six variables, with no more than one remaining variable worsening by >30% (Consolaro 2016). Similarly, the ACR Pedi 50, 70, 90 and 100 response definitions require 50%, 70%, 90% and 100% improvement, respectively, in at least three core set variables without worsening of more than one variable by greater than 30%. Longitudinal treatment effects over six months were comparable between two treatment groups in ACR 30 = ‐0.70 (95% CI ‐1.86 to 0.52), ACR 50 = ‐0.65 (95% CI ‐1.74 to 0.44), ACR 70 = ‐0.61 (95% CI ‐1.89 to 0.74), ACR 90 = ‐0.46 (95% CI ‐3.38 to 2.46) and ACR 100 = ‐1.23 (95% CI ‐2.34 to ‐0.14).

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results (−2).

Mean change from baseline in number or change of dosage of topical or systemic steroid

One included study investigated the change in dosage of topical and systemic steroid doses (SYCAMORE). At baseline, six participants (five in the adalimumab group and one in the placebo group) were taking systemic glucocorticoids (median dose of 0.14 mg per kg per day of prednisone). Three of the participants in the adalimumab group ceased systemic glucocorticoids (median duration 18.1 weeks) and one participant in the placebo group stopped taking systemic glucocorticoids after 5.6 weeks.

The evidence suggests that adalimumab may result in a reduction of topical steroid doses. Of participants taking two or more drops of topical glucocorticoids per day at baseline, 23 (51%) participants in the adalimumab group and three (17%) participants in the placebo group demonstrated a reduction to less than two drops (hazard ratio for reduction 3.72; 95% CI 1.09 to 12.71; 63 participants). Similarly, 23 (47%) in the adalimumab group compared to four (16%) in the placebo group, who were taking one or more drops at baseline, had a reduction to zero drops (hazard ratio 3.58; 95% CI 1.24 to 10.32; 74 participants).

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results (−2).

Need for periocular steroids

None of the included studies evaluated this outcome.

Adverse effects

Three included studies with 134 participants reported adverse events. In Smith 2005, no serious adverse events were reported; ADJUVITE reported that no treatment‐related serious adverse events were observed. In SYCAMORE, the rate of serious adverse events was 0.29 events per patient‐year (95% CI 0.15 to 0.43) and 0.19 events per patient‐year (95% CI 0.00 to 0.40) in the adalimumab and placebo group, respectively.

Development of ocular complications

The three included studies with 134 participants provided data on different ocular complications. In SYCAMORE, participants on adalimumab developed cataract (one event), macular edema (one event) and elevated ocular pressure (seven events in four participants). All events were deemed 'not related' to the investigational medicinal product. No ocular complications were observed in the placebo group. In Smith 2005, two participants (one etanercept and one placebo) experienced a 10‐letter (0.2 logMAR) vision loss in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA). In ADJUVITE, two participants (one in the adalimumab group and one in the placebo group) developed ocular hypertonia.

Infections

All included studies provided data on infections, although none of the studies described the incidence of antibiotic use as a measure of infection (ADJUVITE; Smith 2005; SYCAMORE).

Systemic complications

Two included studies reported data on systemic complications.

One study reported treatment‐related and non‐treatment‐related systemic complications (SYCAMORE), while the other did not clarify whether complications were related or not related to the treatment (ADJUVITE). The pooled analyses of these studies suggested that adalimumab may increase the risk of having injection site reactions (rate ratio 9.88; 95% CI 4.69 to 20.78) and gastrointestinal disorders (rate ratio 4.78; 95% CI 2.72 to 8.38)(Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors versus placebo (per review protocol), Outcome 3: Systemic adverse events

We were not able to combine the data from two studies for the following systemic adverse events because number of events was zero in either or both arms. Five events of blood or lymphatic system disorders were observed in adalimumab arm (one non‐treatment‐related increased tendency to bruise, three lymphadenopathy, one neutropenia) in one study (SYCAMORE), and one case of cervical adenitis in adalimumab arm was reported in the other study (ADJUVITE). Eighty (42 related to treatment) and seven (2 related to treatment) respiratory disorders were observed in the adalimumab and placebo arms, respectively, in SYCAMORE (rate ratio 11.43; 95% CI 5.28 to 24.74); one respiratory adverse event (cough) was reported in ADJUVITE. Five participants in adalimumab arm experienced neoplasia (skin papilloma) (one event each participant, four were recognized as treatment related)(SYCAMORE).

Hospitalization, surgical or medical procedures

One included study included data on hospitalizations, surgical and medical procedures (SYCAMORE):

adalimumab two events (one testicular exploration, one antiviral prophylaxis) (0 deemed related to the investigational medicinal product);

placebo zero events.

We judged the certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgrading two levels for imprecision of results (−2).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review aimed to review and synthesize available evidence from randomized controlled trials(RCTs) on anti‐tumor necrosis factor (TNF) treatments for juvenile idiopathic ‐uveitisJIA‐U. Three RCTs with 134 participants were included (ADJUVITE; Smith 2005; SYCAMORE). We identified one ongoing study for which outcome data have not been reported and thus not included in this review (ADJUST).

The primary outcome time point was changed from 'three months' to 'two to six months' given a lack of data at three months reported from the included studies.

Our analysis of predefined primary outcomes, treatment success and failure did not demonstrate a beneficial effect of TNF inhibitors. Sample sizes were small and there was heterogeneity in outcome measures among the studies. One study showed that a greater proportion of participants on adalimumab were able to taper topical steroids compared to placebo.

Post hoc, we also analyzed the primary outcomes using each individual trial's definition of treatment response and failure. This demonstrated a positive effect of TNF inhibitors for both outcomes. Almost all the evidence was on adalimumab and was very limited for etanercept.

There was no apparent treatment effect on outcomes such as uveitis recurrence, visual acuity, quality of life or ocular complications, although not all of these outcomes were consistently reported among the included studies. The relatively short follow‐up times and small sample sizes limit the ability to detect any differences in such outcomes. Only one study reported on arthritis activity composite measure outcomes (Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response); only a small proportion of patients had active arthritis and clinically meaningful differences were not noted between the adalimumab and placebo groups.

Adverse events including injection site reactions and infections were more common in the TNF inhibitor group. Serious adverse events were uncommon, but also seen more frequently in the active groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this review, we were not able to pool the results for the initial prespecified outcomes due to lack of standardized outcome measures. A post hoc analysis was therefore performed using the individual outcomes measures as defined by each trial. Heterogeneity of populations, treatment regimens and outcome measures make meaningful comparisons between studies challenging (Mastrangelo 2019). This issue has been identified and is being addressed by childhood uveitis working groups; standardized definitions for response to treatment have been recently proposed (Foeldvari 2019) and classification criteria for JIA‐U established (SUN Working Group 2021).

We contacted authors to acquire additional data to assess our outcome measures but were either not able to access further data (ADJUVITE; Smith 2005) or were unable to extract these measures despite a review of anonymized individual patient data (SYCAMORE). Further review of original data could be used for reanalysis in future review updates.

This review included patients with JIA‐U and a few patients with: idiopathic chronic anterior uveitis (ICAU). Given the rarity of these conditions and the similarities with regard to their physiology and response to treatment, it seemed reasonable to pool these patients (Heiligenhaus 2020). Many patients had relatively low levels of inflammation at inclusion and most were biological treatment‐naive. Extrapolation of these results to patients with severe or refractory disease may be somewhat limited.

Only two anti‐TNF medications were included in this analysis. Anti‐TNF monoclonal antibodies have subtle differences between one and another, so caution must be taken when extrapolating these results to other medications in this class.

As well as challenges with pooling results due to differing outcome measures, several important outcome measures such as quality of life assessments were inconsistently reported. This is perhaps due to a lack of reproducible, valid and child‐appropriate patient‐reported outcome measures (Solebo 2019). Child‐specific measures have been proposed but have not yet been broadly adopted (Cassedy 2020).

Quality of the evidence

The three included studies were graded as low risk of bias in most domains. We graded the certainty of evidence to be low or very low, downgrading due to imprecision as only one or two studies provided the outcome data for pre‐specified outcomes. This review included one study in which a few participants with ICAU (6.5%) were also enrolled. We elected to include this study on the basis of a few ICAU participants and known similarity between JIA‐U and ICAU (Heiligenhaus 2020). However, we downgraded one level for certainty of primary outcome evidence due to indirectness.

Potential biases in the review process

We used standard Cochrane methodology to minimize bias to conduct this systematic review. An information specialist performed highly sensitive database searches to identify potentially eligible studies. We reported our findings to follow Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) standards for the reporting of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews (editorial-unit.cochrane.org/mecir). Several protocol changes were made post hoc given the unavailability of data from included studies for the initial outcome measures and time points. None of the review authors had any financial conflict of interest. One author is a site principal investigator for ADJUST, which is noted to be an ongoing study relevant to this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Conclusive outcomes were hard to establish due to small sample sizes and differing definitions of treatment response and failure. Using our primary analysis, we were not able to extract data for the majority of included participants and did not identify a clear treatment effect. A post hoc analysis that was more inclusive with regard to outcomes measures allowed us to assess all included studies and showed a beneficial effect on response and failure that favored TNF inhibitor treatment. Adalimumab studies resulted in positive efficacy outcomes while evidence was inconclusive on etanercept.

Previous systemic reviews of treatment of chronic uveitis have suggested a positive treatment effect for anti‐TNF monoclonal antibodies (particularly adalimumab and infliximab) compared with fusion proteins (etanercept), although they have not adhered to Cochrane methodology and have been largely reliant on observational studies. One review published in 2014 assessed rates of improvement according to the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria among children with chronic childhood uveitis, the majority of whom had JIA‐U (Simonini 2014). Twenty‐two retrospective chart reviews and one randomized controlled trial (Smith 2005) were included. The reviewers estimated response rates of 87% (95% CI 75% to 98%) for adalimumab, 72% (95% CI 64% to 79%) for infliximab, and 33% (95% CI 19% to 47%) for etanercept. A recent systemic review on adult chronic uveitis identified three hig‐ quality placebo‐controlled RCTs (two adalimumab, one etanercept) (Leal 2019). In keeping with observations from pediatric studies, the authors concluded that adalimumab decreases the risk of worsening visual acuity and improves ocular inflammation outcomes, while etanercept does not.

These findings are supported by large‐scale patient registries;a recent Italian registry described 153 JIA‐U patients refractory to standard immunosuppressive therapy and using anti‐TNF treatment with at least two years of follow‐up data (Cecchin 2018). Almost half achieved clinical remission and rates of flare and ocular damage were significantly decreased compared to pre‐anti‐TNF treatment. Contemporary cohorts with access to biologic therapies have also identified lower rates of visual impairment and ocular damage when compared to historical data (Cann 2018).

The role of etanercept in JIA‐U is less clear, with mixed results across retrospective cohort studies and registries. A cohort study published in 2007 examined the efficacy of infliximab and etanercept among 45 patients with JIA‐U (Tynjala 2007). Infliximab was found to be superior with regard to inflammatory activity improvement and frequency of uveitis flares. Uveitis developed for the first time in four patients taking etanercept (2.2/100 patient years) and one patient taking infliximab (1.1/100 patient years). Additionally, a North American study identified two cases of incident uveitis among etanercept‐treated patients (N = 48) and none among infliximab‐exposed patients (N = 22) (Saurenmann 2006). There have been several other reports of a first manifestation or recurrence of JIA‐U occurring among patients treated with etanercept (Heiligenhaus 2019). On the other hand, a German registry of 3467 biologic‐treated JIA patients found a very low rate of uveitis and no association with etanercept (Foeldvari 2019). These discrepant findings perhaps may be partially explained by the placebo effect given the uncontrolled nature of these studies and a high background placebo rate. For context, the reported placebo "response" rate according to the individual trial primary efficacy outcome was 20% in ADJUVITE, 40% in Smith 2005 and 17% in SYCAMORE. The background use of concomitant non‐biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (particularly methotrexate) may also confound these data.

The discrepant findings between anti‐TNF monoclonal antibodies and anti‐TNF fusion proteins are consistent with the known properties of these medications. TNF inhibitors down regulate the pro‐inflammatory TNF pathway via differing mechanisms. Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab bind to soluble and membrane‐bound TNF leading to soluble TNF neutralization as well as antibody‐dependent and complement‐dependent cytotoxicity. Certolizumab also binds to soluble and cell‐bound TNF but does not induce complement activation, cytotoxicity or apoptosis to the same extent. Fusion proteins such as etanercept deplete circulating TNF by acting as a competitive soluble TNF receptor but do not cause cytotoxicity (Cordero‐Coma 2015; Nesbitt 2007). There are several hypotheses to explain the superior efficacy of monoclonal antibodies compared to fusion proteins including the relative inability of fusion proteins to inhibit TNF signaling events, irreversibly neutralize soluble TNF and induce apoptosis of activated monocytes and T‐cells (Nicolela 2020; Wallis 2005).

For these reasons, contemporary consensus guidelines suggest against using etanercept for the treatment of JIA‐U (Angeles‐Han 2019; Angeles‐Han 2019a; Constantin 2018; Heiligenhaus 2019).

There were no new concerning safety signals in the included trials. The observed side effects were consistent with the known profile of anti‐TNF medications and with previous trials in diseases such as JIA (Lovell 2000; Lovell 2008).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The small number of eligible studies that had enrolled small numbers of participants and challenges with extracting heterogenous outcome measures limited our ability to perform planned analysis. On assessment of all available randomized trials, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors appear to be effective in increasing treatment response and decreasing flare when compared to placebo. Two studies on adalimumab showed a positive treatment effect, while the results were inconclusive with regard to outcomes including visual acuity and ocular complications although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are typically designed to avoid these adverse events through pre‐defined safety protocols. The duration of the included trials may not have been long enough to detect such outcomes. Adverse events attributable to TNF inhibitors in juvenile idiopathic arthritis‐associated uveitis (JIA‐U) trials are in keeping with the known side effect profile of these medications.

Implications for research.

This review highlights some challenges with studying childhood uveitis. Heterogeneity of outcome measures is a major issue that limits pooling of results and accurate comparisons between studies (Mastrangelo 2019). While specific clinical questions may demand the use of differing outcome measures, we advocate inclusion of some standard measures in the future trials and other comparative studies. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria provide a useful framework for objectively recording aspects of ocular inflammation but fall short of providing a complete assessment (Jabs 2005). Work towards developing and validating disease‐specific and child‐appropriate outcome measures is welcomed. Outcome domains including response to treatment, inactive disease state and damage have been recently proposed by an interdisciplinary working group (Foeldvari 2019). These are important outcomes in the context of highly effective contemporary treatments and a treat‐to‐target approach to inflammatory diseases. Additional patient‐focussed outcomes such as medication‐related toxicity and disease specific health‐related quality of life outcomes should also be considered.

The clinical course, treatment, and response to corticosteroids and disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is similar between patients with JIA‐U and childhood onset antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive idiopathic uveitis (Heiligenhaus 2020). Given the rarity of these conditions and the difficulties with performing pediatric RCTs, it may be reasonable to pool these groups and design studies with mixed populations in addition to pooling outcomes from studies of each condition.

Monoclonal anti‐TNF agents should be analyzed separately to anti‐TNF fusion proteins given their inherent pharmacological and clinical differences. As other TNF‐inhibitors, such as golimumab, emerge as treatments for JIA (Brunner 2018), specific analyses on their efficacy in JIA‐U should be examined.

Ongoing studies may add important information regarding the efficacy of existing medications such as adalimumab (ADJUST). Future reviews should aim to include existing studies and may need access to anonymized individual patient data in order to extract adequate outcome data.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 12, 2020

Risk of bias

Risk of bias for analysis 1.1 Treatment success defined as 0 to trace cells; or 2‐step decrease in activity using in SUN anterior chamber (AC) cell grading.

| Study | Bias | |||||||||||

| Randomisation process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall | |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | |

| ADJUVITE | Low risk of bias | “The random assignment sequence stratified on age (<13 or ≥13 years) and using blocks of size four was computer‐generated at Paris Descartes Clinical Research Unit.” “Some differences between both group can be noticed such as the proportion of patients with bilateral uveitis, cataract or on MTX treatment at baseline.” No tests for between group differences reported. The study is small and differences are likely due to chance. |

Low risk of bias | "Blinded injections were realised in consultation at day (D)0, D14, month (M)1 visit and at home at D42."; "At each visit, there was an assessment by two investigators, first an ophthalmologist, then a paediatrician or a rheumatologist, to check the absence of contraindication to maintain the patient in the trial and to assess treatment tolerance. These two assessors were blinded to each other following D0 visit and the first injection of study treatment."; "Treatment effect size was presented as a relative risk and 95% CI using a log‐binomial regression model." | Low risk of bias | "All but one patient received at least one study treatment injection; the latter withdrew from study before the first administration and was thus excluded from ITT population." | Some concerns | "The primary outcome was response to treatment at the end of double‐blind period (M2), defined as a reduction of at least 30% of ocular inflammation quantified by LFP without worsening of cell counts or protein flare on SL examination according to SUN criteria, in the assessable eye with more severe baseline inflammation."; "Method of analysis by laser flare photometry (Kowa FM‐500, Kowa Compagny, Ltd., Electronics and Optics Divison, Tokyo, Japan)" "At each visit, there was an assessment by two investigators, first an ophthalmologist, then a paediatrician or a rheumatologist, to check the absence of contraindication to maintain the patient in the trial and to assess treatment tolerance. These two assessors were blinded to each other following D0 visit and the first injection of study treatment." | Low risk of bias | The analysis plan for primary outcome reported in trial register was matched with the final report. | Low risk of bias | Please see the datails in each bias domain |

| Smith 2005 | Low risk of bias | Participants were randomized at baseline in a 2:1 fashion to receive etanercept or placebo. No statistical comparison results between the two intervention groups were reported. The participant accrual period was closed earlier than expected due to a failure to meet its projected accrual goal of 15 participants through 18 months of enrollment. | Low risk of bias | Participants would discontinue the randomized treatment and either withdraw from the study or initiate open‐label etanercept if they met a failure or safety outcome within the (first 6 month) masked portion of the study. Clinic staff and study investigators remained masked to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. Differences in event rates between the 2 groups were tested using a 2‐sided Fisher's exact test. | Low risk of bias | Data for the primary end point were available for all the participants who underwent randomization. | Low risk of bias | The primary outcomes for successful treatment of uveitis were a reduction of anterior chamber cells to 0 or trace while using corticosteroid drops < 3 times a day or a 50% reduction in the number of dosage of other anti‐inflammatory medications without an increase in inflammation. The standardization of grading anterior chamber cellular infiltration was not reported in the article but might be an objective tool in clinical routine. Clinic staff and study investigators remained masked to treatment assignments for the duration of the study. | Low risk of bias | The study was powered to detect differences in success rates, which were the primary efficacy outcomes compared and reported. | Low risk of bias | Please see each domain shown above. |

Risk of bias for analysis 1.2 Treatment failure defined as 2‐step increase in SUN anterior chamber (AC) cell grading.

| Study | Bias | |||||||||||

| Randomisation process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall | |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | |

| ADJUVITE | Low risk of bias | “The random assignment sequence stratified on age (<13 or ≥13 years) and using blocks of size four was computer‐generated at Paris Descartes Clinical Research Unit.” “Some differences between both group can be noticed such as the proportion of patients with bilateral uveitis, cataract or on MTX treatment at baseline.” No tests for between group differences reported. The study is small and differences are likely due to chance. |

Low risk of bias | “Blinded injections were realised in consultation at day (D)0, D14, month (M)1 visit and at home at D42.” “The double‐blind phase lasted from D0 until M2, except in the case of dropout from the trial. From visit M2, all patients who continued the trial received adalimumab treatment during 10 months (open‐labelled phase). Visits were held at M3, M4, M6, M9 and M12.” “All statistical analyses were undertaken using R V.2.11.1 software, and in accordance with the statistical analysis plan prespecified before the lock of the database. Statistical tests were two‐sided and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Primary outcome was compared between groups using ×2 test. Primary analysis was done on the ITT population, with patients who prematurely ended double‐blind period or non‐assessable patients considered as non‐responders. No other imputation method of missing data was considered due to the small sample size. Treatment effect size was presented as a relative risk and 95%CI using a log‐binomial regression model.” |