Key Points

Question

Are the changes in approaches to radiation and chemotherapy treatment for children with cancer over time associated with changes in risk for breast cancer among long-term cancer survivors?

Findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of 11 550 female survivors of childhood cancer, the risk of breast cancer modestly decreased with time, which was largely associated with the decreased use of chest radiotherapy, although the risk was tempered by concurrent changes in other therapies.

Meaning

Ongoing efforts to both improve survival outcomes and minimize long-term toxic effects in the treatment of childhood cancer were associated with decreasing risk of breast cancer over time.

This cohort study examines the association between temporal changes in cancer treatment between 1970 and 1999 and subsequent breast cancer risk among women.

Abstract

Importance

Breast cancer is the most common invasive subsequent malignant disease in childhood cancer survivors, though limited data exist on changes in breast cancer rates as primary cancer treatments have evolved.

Objective

To quantify the association between temporal changes in cancer treatment over 3 decades and subsequent breast cancer risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 5-year cancer survivors diagnosed when younger than 21 years between 1970 and 1999, with follow-up through December 5, 2020.

Exposures

Radiation and chemotherapy dose changes over time.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Breast cancer cumulative incidence rates and age-specific standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) compared across treatment decades (1970-1999). Piecewise exponential models estimated invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) risk and associations with treatment exposures, adjusted for age at childhood cancer diagnosis and attained age.

Results

Among 11 550 female survivors (median age, 34.2 years; range 5.6-66.8 years), 489 developed 583 breast cancers: 427 invasive, 156 DCIS. Cumulative incidence was 8.1% (95% CI, 7.3%-9.0%) by age 45 years. An increased breast cancer risk (SIR, 6.6; 95% CI, 6.1-7.2) was observed for survivors compared with the age-sex-calendar-year-matched general population. Changes in therapy by decade included reduced rates of chest (34% in the 1970s, 22% in the 1980s, and 17% in the 1990s) and pelvic radiotherapy (26%, 17%, and 13% respectively) and increased rates of anthracycline chemotherapy exposures (30%, 51%, and 64%, respectively). Adjusting for age and age at diagnosis, the invasive breast cancer rate decreased 18% every 5 years of primary cancer diagnosis era (rate ratio [RR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74-0.90). When accounting for chest radiotherapy exposure, the decline attenuated to an 11% decrease every 5 years (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.99). When additionally adjusted for anthracycline dose and pelvic radiotherapy, the decline every 5 years increased to 14% (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77-0.96). Although SIRs of DCIS generally increased over time, there were no statistically significant changes in incidence.

Conclusions and Relevance

Invasive breast cancer rates in childhood cancer survivors have declined with time, especially in those younger than 40 years. This appears largely associated with the reduced use of chest radiation therapy, but was tempered by concurrent changes in other therapies.

Introduction

More than 85% of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer will survive 5 years, and as of 2018 it is estimated that more than 483 000 survivors are in the US.1 Although 5-year survival has improved over time, the annual number of excess deaths for survivors of all ages remains high because survivors of cancer have significantly elevated risk of premature mortality.2 Subsequent malignant neoplasms (SMN) are a leading cause of late mortality.3 Among cancer survivors treated in the 1970s and 1980s, breast cancer is the most frequent SMN, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer.4,5 Invasive breast cancer in survivors is often accompanied by multiquadrant ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS).6,7 Invasive breast cancer presents most often in early stages, and the distribution of stage and biology at diagnosis are similar to patients with de novo breast cancer.8,9 Breast cancer risk in this era is largely driven by exposure to chest radiation therapy (RT) in a linear risk-dose relationship, with risk affected by field, attenuated by radiation to the ovaries, and potentially modulated by exposure to alkylating agents.10,11,12,13,14,15,16 There is an independent, elevated breast cancer risk associated with increasing anthracycline chemotherapy dose.17,18,19 Importantly, survivors with a subsequent breast cancer have a substantially greater risk of dying within 10 years following diagnosis compared with women with de novo breast cancer.8,20

Approaches to childhood cancer treatment and survivorship care have evolved over recent decades.21,22 Specifically for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), treatment regimens have evolved since the 1970s. In addition to fewer survivors of HL being exposed to RT, RT now includes lower doses (10-25 Gy vs 35-45 Gy) and reductions in the breast tissue volume exposed.23,24 Conversely, there has been increasing use of multiagent chemotherapy, for both HL and all other primary diagnoses.3 Although studies suggest reduced breast cancer risk after treatment with smaller RT fields, studies with patients treated in the 1990s are limited in size and follow-up.12,14,15,25,26,27,28 We examined breast cancer risk among a large cohort of childhood cancer survivors treated over 3 decades (1970-1999) and evaluated how rates changed as treatment exposures evolved.

Methods

Study Population

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a retrospective cohort of childhood cancer survivors treated at 31 North American centers.29,30 Eligibility criteria included: (1) diagnosis of leukemia, central nervous system cancer, HL, non-HL, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, kidney tumor, or bone cancer; (2) diagnosis between 1970 to 1999; (3) younger than 21 years at diagnosis; (4) alive 5 years from diagnosis. Participating centers’ institutional review boards approved the study. Participants provided informed consent. This analysis includes 11 550 female participants.

Ascertainment of Treatment Information

Therapeutic exposures within the 5 years following childhood cancer diagnosis were ascertained through medical record abstraction.29 Cumulative anthracyclines, alkylators (presented as cyclophosphamide equivalent doses [CED])31 were ascertained.31,32,33 For chest-directed RT, the chest maximum target dose was determined by summing the prescribed dose from all overlapping chest fields.34 Chest field type was stratified by mantle, mediastinal/involved field, whole lung, spine, or other. Pelvic RT and total body irradiation were defined as yes/no.

Confirmation of Subsequent Breast Cancer

Invasive breast cancer and DCIS cases were ascertained through self or proxy report and the National Death Index. A pathologist (M.A.) and a nonauthor oncologist independently confirmed cases with pathology reports or, if they could not be obtained, medical records or death certificates.

Statistical Analysis

Survivors were considered at risk for breast cancer beginning 5 years after childhood cancer diagnosis, and ending at the earliest of death, prophylactic mastectomy (N = 27), or censoring at the most recent questionnaire completion. Breast cancer cumulative incidence was estimated using age as the time scale, treating death and prophylactic mastectomy as competing risk events that terminate the follow-up of participants at risk for subsequent breast cancer. Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) and absolute excess risk (AER) per 1000 person-years were calculated using age-, sex- and calendar-year-specific cancer incidence rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program as reference rates.35 To account for potential confounding by attained age (ie, time-dependent age during each survivor’s follow-up), SIRs were calculated stratifying on 10-year age intervals.

Multivariable piecewise-exponential models estimated relative rates (RRs) and 95% CIs of invasive breast cancer and DCIS, associated with therapeutic exposures and 5-year treatment eras, adjusting for attained age as cubic splines, age at diagnosis, and censoring individuals at the date of death or prophylactic mastectomy. Individuals with multiple primary breast cancers were included and accounted for as repeated events using generalized estimating equations.36 To assess breast cancer rates associated with treatment approach changes, the adjusted rate changes by every 5-year treatment era increment were estimated with and without adjustment for treatment variables in the same model. The CCSS expansion cohort (childhood cancer diagnosis 1987-1999) undersampled acute lymphocytic leukemia survivors to efficiently sample all diagnosis groups with a fixed resource. Analyses were weighted to account for all undersampling.

We conducted sensitivity analyses that considered late recurrence and SMN other than breast cancer as competing-risk events to remove the potential influence of treatment exposures associated with these events, which were not collected in the cohort.

We used SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute) and R statistical software (version 3.6.0, R Foundation). Statistical inferences were 2-sided and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 11 550 female survivors (median age, 34.2 years; range 5.6-66.8 years), 489 developed 583 breast cancers (Table 1). One-hundred forty-one female patients had 156 DCIS diagnosed; 384 had 427 invasive breast cancers diagnosed (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The median (range) time from primary cancer to breast cancer was 25.6 (6.7-47.4) years. The median (range) age at breast cancer diagnosis was 40.3 (19.9-62.1) years.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Female Survivors of Childhood Cancera.

| Characteristic | Total | Decade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 11 550) | BC (n = 489) | 1970-1979 | 1980-1989 | 1990-1999 | ||||

| Total (n = 2900) | BC (n = 251) | Total (n = 4156) | BC (n = 182) | Total (4,454) | BC (n = 56) | |||

| Childhood cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Leukemia | 3672 (41) | 65 (14) | 986 (34) | 30 (12) | 1599 (42) | 31 (18) | 1087 (45) | 4 (12) |

| CNS | 2002 (15) | 9 (2) | 331 (11) | 7 (3) | 684 (14) | 1 (1) | 987 (18) | 1 (2) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1476 (11) | 273 (55) | 511 (18) | 144 (57) | 482 (10) | 94 (51) | 483 (9) | 35 (59) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 659 (5) | 21 (4) | 141 (5) | 6 (2) | 247 (5) | 13 (7) | 271 (5) | 2 (3) |

| Wilms tumor | 1250 (9) | 22 (4) | 273 (9) | 14 (6) | 504 (10) | 8 (4) | 473 (8) | 0 |

| Neuroblastoma | 987 (7) | 9 (2) | 228 (8) | 6 (2) | 366 (7) | 2 (1) | 393 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Bone cancer | 993 (7) | 75 (15) | 277 (10) | 33 (13) | 370 (8) | 29 (16) | 346 (6) | 13 (22) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 511 (4) | 15 (3) | 153 (5) | 11 (4) | 204 (4) | 4 (2) | 154 (3) | 0 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||

| 0-4 | 4806 (45) | 30 (6) | 1144 (39) | 18 (7) | 1982 (46) | 12 (6) | 1680 (46) | 0 |

| 5-9 | 2460 (22) | 35 (8) | 623 (21) | 21 (8) | 941 (22) | 11 (7) | 896 (23) | 3 (5) |

| 10-14 | 2458 (19) | 180 (37) | 610 (21) | 91 (36) | 888 (19) | 65 (35) | 960 (19) | 24 (46) |

| ≥15 | 1826 (14) | 244 (49) | 523 (18) | 121 (48) | 645 (13) | 94 (51) | 658 (12) | 29 (49) |

| Age at the end of follow-upb | ||||||||

| 5-14 | 360 (3) | 0 | 85 (3) | 0 | 146 (3) | 0 | 129 (3) | 0 |

| 15-19 | 652 (6) | 1 | 77 (3) | 0 | 230 (5) | 0 | 345 (9) | 1 (2) |

| 20-24 | 1314 (13) | 12 (3) | 133 (5) | 5 (2) | 363 (8) | 1 (1) | 818 (22) | 5 (13) |

| 25-29 | 1815 (18) | 29 (6) | 186 (6) | 13 (5) | 507 (11) | 4 (2) | 1122 (30) | 4 (7) |

| 30-34 | 1978 (18) | 84 (18) | 283 (10) | 27 (11) | 843 (22) | 24 (14) | 852 (19) | 24 (41) |

| 35-39 | 2016 (16) | 117 (24) | 324 (11) | 60 (24) | 1038 (23) | 32 (17) | 654 (12) | 14 (24) |

| 40-44 | 1427 (11) | 121 (24) | 531 (18) | 61 (24) | 648 (14) | 47 (25) | 248 (5) | 8 (14) |

| 45-49 | 1045 (8) | 85 (17) | 561 (19) | 53 (21) | 458 (9) | 48 (26) | 26 | 0 |

| 50-54 | 555 (4) | 33 (7) | 372 (13) | 25 (10) | 183 (4) | 20 (11) | 0 | 0 |

| 55-59 | 306 (2) | 7 (1) | 266 (9) | 7 (3) | 40 (1) | 6 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| ≥60 | 82 (1) | 0 | 82 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chest RTc | ||||||||

| No | 7838 (78) | 148 (34) | 1688 (66) | 68 (29) | 3046 (78) | 62 (39) | 3104 (83) | 18 (37) |

| Yes | 2622 (22) | 304 (66) | 856 (34) | 167 (71) | 919 (22) | 102 (61) | 847 (17) | 35 (63) |

| Primary chest radiation field | ||||||||

| None | 7838 (78) | 148 (34) | 1688 (66) | 68 (29) | 3046 (78) | 62 (39) | 3104 (83) | 18 (37) |

| Mantle | 930 (8) | 225 (49) | 366 (14) | 121 (51) | 319 (7) | 81 (49) | 245 (5) | 23 (41) |

| Mediastinal/IFRT | 331 (3) | 25 (5) | 131 (5) | 17 (7) | 104 (2) | 5 (3) | 96 (2) | 3 (5) |

| Whole lung | 226 (2) | 23 (5) | 71 (3) | 17 (7) | 83 (2) | 5 (3) | 72 (1) | 1 (2) |

| TBI | 266 (3) | 15 (3) | 22 (1) | 1 (0) | 83 (2) | 8 (5) | 161 (4) | 6 (11) |

| Spine | 620 (5) | 6 (1) | 188 (7) | 6 (3) | 235 (6) | 0 | 197 (4) | 0 |

| Other | 249 (2) | 10 (2) | 78 (3) | 5 (2) | 95 (2) | 3 (2) | 76 (1) | 2 (4) |

| Chest radiation doses, Gyd | ||||||||

| None | 7838 (78) | 148 (34) | 1688 (67) | 68 (29) | 3046 (78) | 62 (39) | 3104 (83) | 18 (37) |

| <10 | 97 (1) | 2 (0) | 21 (1) | 1 (0) | 48 (1) | 1 (1) | 28 (1) | 0 |

| 10-19 | 622 (6) | 42 (9) | 122 (5) | 22 (9) | 239 (6) | 13 (8) | 261 (6) | 7 (13) |

| 20-29 | 734 (6) | 56 (12) | 205 (8) | 17 (7) | 211 (5) | 21 (13) | 318 (6) | 18 (32) |

| 30-39 | 628 (5) | 95 (21) | 264 (10) | 62 (26) | 224 (5) | 29 (18) | 140 (3) | 4 (7) |

| ≥40 | 520 (4) | 107 (23) | 235 (9) | 64 (27) | 191 (4) | 37 (22) | 94 (2) | 6 (11) |

| Alkylating agents | ||||||||

| No | 5133 (47) | 197 (42) | 1404 (54) | 120 (51) | 1862 (46) | 65 (38) | 1867 (45) | 12 (21) |

| Yes | 5542 (53) | 264 (58) | 1174 (46) | 117 (49) | 2185 (54) | 105 (62) | 2183 (55) | 42 (79) |

| Cyclophosphamide equivalent dose, mg/m2 | ||||||||

| 0 | 5133 (51) | 197 (48) | 1404 (61) | 120 (58) | 1862 (50) | 65 (43) | 1867 (47) | 12 (22) |

| 1-5999 | 1900 (22) | 53 (14) | 253 (11) | 16 (8) | 812 (22) | 23 (17) | 835 (26) | 14 (30) |

| 6000-17 999 | 2326 (23) | 134 (33) | 464 (20) | 59 (29) | 968 (25) | 56 (37) | 894 (22) | 19 (35) |

| ≥18 000 | 608 (5) | 23 (6) | 181 (8) | 12 (6) | 139 (3) | 4 (3) | 288 (6) | 7 (13) |

| Anthracyclines | ||||||||

| No | 5589 (47) | 251 (53) | 1804 (70) | 176 (74) | 2088 (49) | 70 (40) | 1697 (36) | 5 (9) |

| Yes | 5114 (53) | 213 (47) | 787 (30) | 63 (26) | 1963 (51) | 101 (60) | 2364 (64) | 49 (91) |

| Anthracycline cumulative dose, mg/m2 | ||||||||

| 0 | 5589 (49) | 251 (56) | 1804 (73) | 176 (76) | 2088 (51) | 70 (43) | 1697 (37) | 5 (9) |

| 1-249 | 3059 (36) | 85 (20) | 277 (11) | 16 (7) | 1100 (32) | 42 (27) | 1682 (51) | 27 (53) |

| ≥250 | 1697 (15) | 108 (24) | 406 (16) | 39 (17) | 716 (17) | 48 (30) | 575 (12) | 21 (38) |

| Pelvic radiation | ||||||||

| No | 8471 (83) | 332 (74) | 1895 (74) | 171 (73) | 3255 (83) | 120 (74) | 3321 (87) | 41 (78) |

| Yes | 1990 (17) | 120 (26) | 650 (26) | 64 (27) | 710 (17) | 44 (26) | 630 (13) | 12 (22) |

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; CNS, central nervous system; IFRT, involved field radiation therapy; RT, radiation therapy; TBI, total body irradiation.

Analyses, including reported percentages and means/medians, were weighted to account for undersampling of acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors (1987-1999).

For the BC columns, we show the distribution of age at the first BC.

Treatment exposures based on available data.

Chest dose was taken as the sum of the prescribed doses from all overlapping fields in the chest.

Eighty-six women (18%) with breast cancer had bilateral disease; 40 (8%) had synchronous breast cancer (≤12 months from first breast cancer), 44 women (9%) developed metachronous breast cancer (>12 months from first breast cancer), 2 were unknown. Sixty-three of the 86 women (73%) with bilateral breast cancer received chest RT (eTable 2 in the Supplement), 18 women (21%) had never been exposed to chest RT, 5 (6%) had missing chest RT information.

Overall, 856 (34%) of the cohort treated in the 1970s received chest RT, only 87 (17%) received it in the 1990s (Table 1). High-dose chest RT exposures (>40 Gy) decreased with time. Use of anthracyclines increased from 787 (30%) to 2364 (64%) between the 1970s and 1990s, predominantly for lower doses (1-249 mg/m2). The proportion of patients treated with pelvic RT decreased from 650 (26%) to 630 (13%), use of alkylating agents increased from 1174 (46%) to 2183 (55%).

Among HL survivors treated in the 1970s, 415 (91%) received chest RT and 58 (13%) received anthracyclines. Among those treated in the 1990s, 325 (72%) were treated with chest RT, whereas 419 (90%) were treated with anthracyclines, with 268 (63%) receiving both (eTable 3 in the Supplement). For survivors of cancers other than HL in the 1970s, 441 (21%) received chest RT and 729 (34%) received anthracyclines. In the 1990s, 522 (12%) received chest RT and 1945 (62%) received anthracyclines.

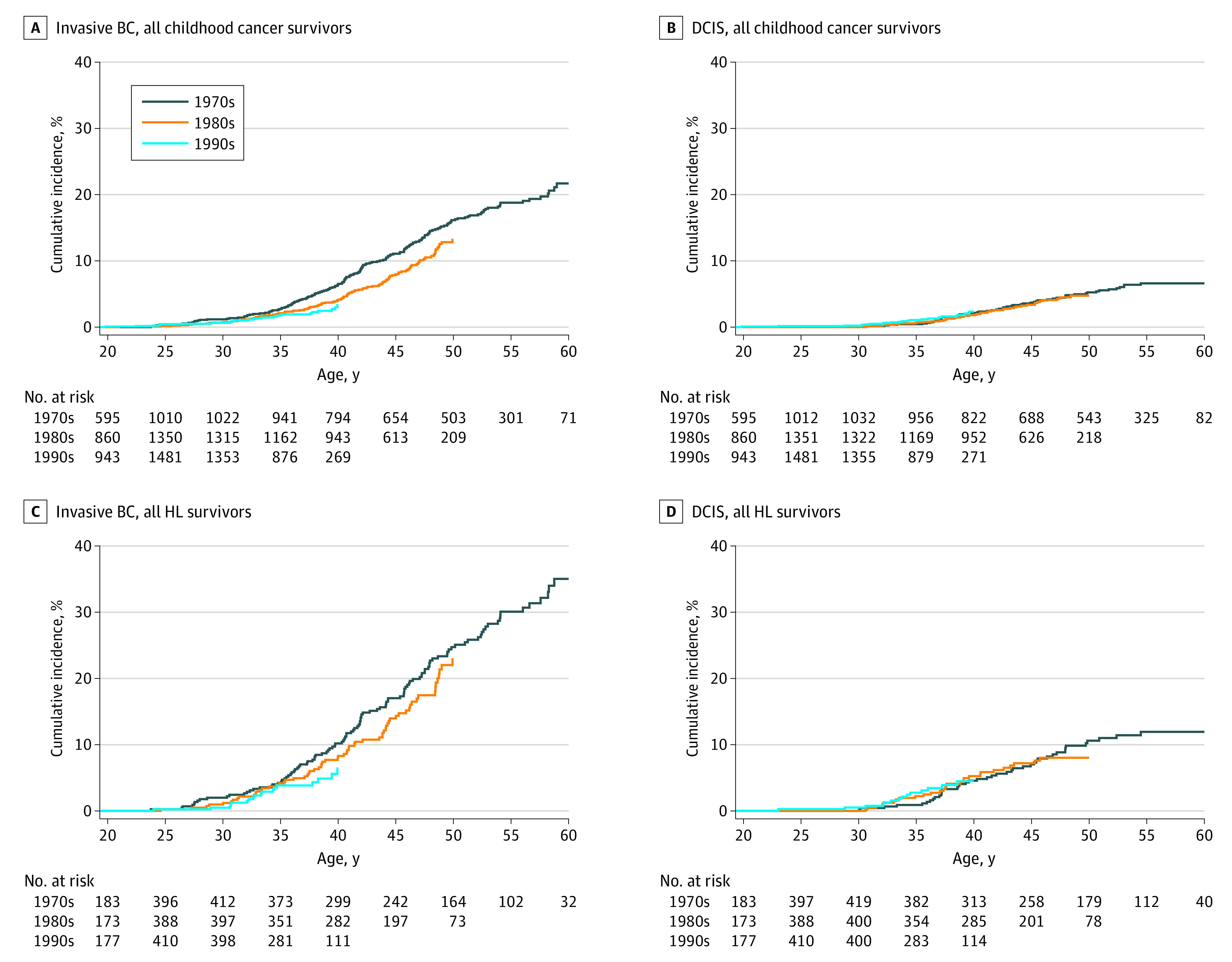

Cumulative Incidence

Overall, the cumulative incidence of breast cancer at age 35 years was 1.6% (95% CI, 1.4%-1.9%), increasing to 8.1% (95% CI, 7.4%-9.0%) by age 45 years, and 18.1% (95% CI, 16.0%-20.1%) by 55 years. For HL survivors, the cumulative incidence of breast cancer at age 35 years was 5.0% (95% CI, 3.8%-6.1%) increasing to 19.3% (95% CI, 16.7%-21.8%) at age 45 years, and to 36.8% (95% CI, 32.4%-41.0%) at 55 years. Although we did not observe a reduction in cumulative incidence of breast cancer for women diagnosed with their primary cancers between 0 and 9 years (eFigure 1, eTable 4 in the Supplement), we saw a reduction of cumulative incidence of women with invasive breast cancers across decades for women diagnosed with their primary cancer between ages 10 and 20 years (Figure 1; eFigures 2-3, eTable 5 in the Supplement). By age 40 years, the cumulative incidence was 8.4% (95% CI, 6.7%-10.0%) in the 1970s, 5.4% (95% CI, 4.2%-6.6%) in the 1980s, and 5.3% (95% CI, 3.5%-7.0%) in the 1990s (Ptrend = .002). When restricted to HL survivors (Ptrend = .06), HL survivors exposed to chest RT (Ptrend = .10), or all survivors except HL survivors (Ptrend = .03), we also observed small, nonsignificant reductions in invasive breast cancers. Notably, when survivors of diagnosed at ages 0 to 20 years are combined, a substantive decrease in breast cancer cumulative incidence was not observed by decade of diagnosis potentially due to confounding between age and decade of primary diagnosis (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Cumulative incidence of DCIS was also not significantly different between decades.

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence Curves by Treatment Decade Among Survivors Diagnosed With Primary Cancer Between Age 10 to 20 Years for Invasive Breast Cancer (BC) and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ.

Relative Rates of Subsequent Breast Cancer

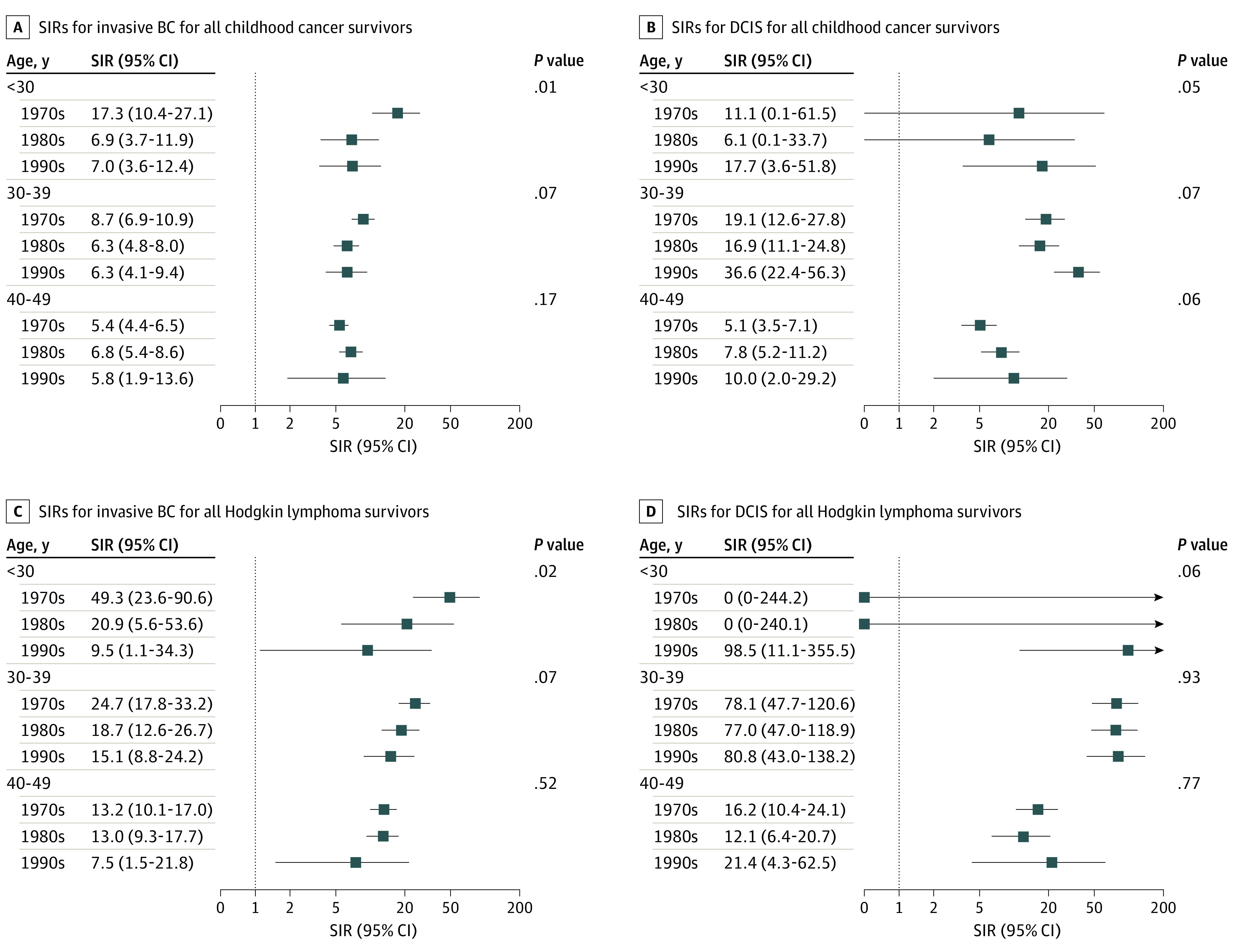

Compared with the general population, the SIR for all breast cancers in the cohort was 6.6 (95% CI, 6.1-7.2) with an AER of 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) per 1000 person-years. The SIR for invasive breast cancer was 6.1 (95% CI, 5.6-6.7) and the AER was 1.3 (95% CI, 1.2-1.4) per 1000 person-years. The SIR for DCIS was 8.5 (95% CI, 7.3-10.0); the AER was 0.5 (0.4-0.6) per 1000 person-years.

We observed a general pattern of decreasing SIRs across decades of childhood cancer diagnosis for invasive breast cancers diagnosed at a young age (≤39 years). This trend was statistically significant for invasive breast cancers diagnosed before age 30 years in the whole cohort and in HL survivors (Figure 2; eFigures 4-5, eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Standardized Incidence Ratios (SIRs) for Invasive Breast Cancer (BC) and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), by Attained Age and Decade of Initial Cancer Diagnosis.

There were no statistically significant changes in SIRs for DCIS by decade overall (or for HL survivors), but SIRs of DCIS were generally increasing over time. Of note, for survivors aged 30 to 39 years, SIRs were particularly high. For example, DCIS SIRs were particularly high among HL survivors aged 30 to 39 years (SIR, 78.1; 95% CI, 47.7-120.6 [1970s], 77.0, 95% CI, 47.0-118.9 [1980s], and 80.8, 95% CI, 43.0-138.2 [1990s]) compared with those aged 40 to 49 years (SIR, 16.2; 95% CI, 10.4-24.1 [1970s], 12.1, 95% CI, 76.4-20.7 [1980s], and 21.4. 95% CI, 4.3-62.5 [1990s]).

Risk Factors for Subsequent Invasive Breast Cancer and DCIS

In multivariable models, exposure to chest RT was associated with higher invasive breast cancer and DCIS risk (Table 2). There was an interactive effect between anthracyclines and chest RT, with high-dose anthracyclines (≥250 mg/m2) significantly associated with both invasive breast cancer and DCIS in women not exposed to chest RT (RR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.48-3.76, and RR, 4.08; 95% CI, 1.45-11.45, respectively). In women exposed to chest RT, exposure to low-dose anthracyclines was associated with elevated DCIS risk (RR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.45-4.96) but not significantly associated with invasive breast cancer risk. In women exposed to chest RT, alkylators showed a protective effect for both invasive cancers and DCIS, although statistical significance was only seen for DCIS (CED 1-5999 RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19-0.81; CED 6000-17 999 RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.31-0.94) and alkylators generally showed an increasing effect for breast cancers, with statistical significance seen with invasive breast cancer. Exposure to pelvic RT was protective for the development of invasive breast cancer (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82) but was not significantly associated with DCIS risk.

Table 2. Risk Factors for Breast Cancer Overall, Invasive Breast Cancer (BC), and DCIS According to Multivariable Analysisa.

| Variable | Any BC | Invasive | DCIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P value | RR (95% CI) | P value | RR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||||

| 0-4 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 5-9 | 1.14 (0.62-2.09) | .67 | 1.24 (0.66-2.31) | .50 | 0.98 (0.28-3.48) | .98 |

| 10-14 | 2.79 (1.72-4.51) | <.001 | 2.92 (1.76-4.84) | <.001 | 3.89 (1.56-9.74) | .004 |

| ≥15 | 2.73 (1.69-4.42) | <.001 | 3.23 (1.93-5.41) | <.001 | 2.99 (1.20-7.43) | .02 |

| Year of diagnosis, every 5 y | 0.93 (0.84-1.04) | .20 | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) | .003 | 1.10 (0.94-1.29) | .24 |

| Chest RT yes vs no | 9.07 (5.86-14.03) | <.001 | 8.44 (5.25-13.58) | <.001 | 13.33 (6.02-29.51) | <.001 |

| Anthracycline in chest RT, no | ||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 1-249 | 1.49 (0.81-2.74) | .20 | 1.66 (0.90-3.05) | .10 | 0.57 (0.11-2.89) | .49 |

| ≥250 | 2.41 (1.53-3.80) | <.001 | 2.36 (1.48-3.76) | <.001 | 4.08 (1.45-11.45) | .008 |

| Anthracycline in chest RT, yes | ||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 1-249 | 1.83 (1.23-2.70) | .003 | 1.23 (0.79-1.92) | .36 | 2.68 (1.45-4.96) | .002 |

| ≥250 | 1.44 (0.86-2.40) | .16 | 1.47 (0.91-2.37) | .12 | 1.49 (0.72-3.06) | .28 |

| CED (mg/m2) in chest RT, no | ||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 1-5999 | 1.06 (0.54-2.08) | .86 | 1.10 (0.55-2.20) | .79 | 0.41 (0.08-2.04) | .28 |

| 6000-17 999 | 1.74 (1.07-2.83) | .03 | 1.74 (1.06-2.86) | .03 | 1.48 (0.53-4.12) | .45 |

| ≥18 000 | 3.36 (1.84-6.15) | <.001 | 3.22 (1.72-6.03) | <.001 | 1.66 (0.41-6.61) | .48 |

| CED (mg/m2) in chest RT, yes | ||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 1-5999 | 0.63 (0.42-0.95) | .03 | 0.72 (0.46-1.13) | .16 | 0.39 (0.19-0.81) | .01 |

| 6000-17 999 | 0.65 (0.47-0.90) | .009 | 0.79 (0.58-1.09) | .15 | 0.54 (0.31-0.94) | .03 |

| ≥18 000 | 0.44 (0.20-0.95) | .04 | 0.50 (0.20-1.22) | .13 | 0.26 (0.06-1.19) | .08 |

| Pelvic RT yes vs no | 0.69 (0.53-0.90) | .007 | 0.62 (0.47-0.82) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.48-1.24) | .29 |

Abbreviations: CED, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; RR, relative rate; RT, radiation therapy.

In addition to the above variables in the model, attained age was adjusted in the model for each outcome using cubic splines.

In a model adjusted for age at diagnosis and attained age, the RR of invasive breast cancer per every 5-year of diagnosis era was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.74-0.90; 18% decrease every 5 years) without accounting for any treatment, but increased to 0.89 (95% CI, 0.81-0.99; 11% decrease every 5 years) once accounting for chest RT exposure, a risk factor decreasing over time, indicating the positive effect of reduction in chest RT use over time on the rate reduction (Table 3). When adjusted for anthracycline dose (a risk factor increasing over time) and pelvic RT dose (a protective factor decreasing over time), the RR attenuated to 0.86 (95% CI, 0.77-0.96; 14% decrease every 5 years), indicating the negative effect of the increase in anthracycline use and the decrease in pelvic RT use. A similar pattern was observed in HL survivors, but not in survivors of other cancers.

Table 3. Relative Rates of Invasive Breast Cancer and DCIS, per 5-Year Treatment Era, Without and With Adjustment for Treatment Variablesa.

| Adjusted treatment variables | Invasive | DCIS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P value | RR (95% CI) | P value | |

| All survivors | ||||

| Not adjusted for treatment | 0.82 (0.74-0.90) | <.001 | 1.10 (0.94-1.28) | .24 |

| Adjusted chest RT | 0.89 (0.81-0.99) | .03 | 1.22 (1.05-1.41) | .009 |

| Adjusted for chest RT, anthracycline dose, and pelvic RTb | 0.86 (0.77-0.96) | .006 | 1.13 (0.97-1.32) | .11 |

| HL survivors | ||||

| Not adjusted for treatment | 0.90 (0.80-1.01) | .07 | 1.14 (0.97-1.35) | .12 |

| Adjusted chest RT | 0.98 (0.86-1.11) | .73 | 1.20 (0.99-1.45) | .06 |

| Adjusted for chest RT, anthracycline dose, and pelvic RTb | 0.94 (0.81-1.10) | .45 | 1.03 (0.83-1.28) | .79 |

| Survivors other than HL | ||||

| Not adjusted for treatment | 0.82 (0.70-0.97) | .02 | 1.36 (1.04-1.78) | .03 |

| Adjusted chest RT | 0.83 (0.70-0.97) | .02 | 1.40 (1.06-1.84) | .02 |

| Adjusted for chest RT, anthracycline dose, and pelvic RTb | 0.79 (0.67-0.94) | .007 | 1.41 (1.08-1.85) | .01 |

Abbreviations: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; RR, relative rate; RT, radiation therapy.

All models adjusted for attained age as cubic splines and age at diagnosis. The addition of cyclophosphamide equivalent dose to the model does not change the slope of the 5-year treatment era and hence is not shown.

The mode included the interaction of chest RT by anthracycline dose.

There was an increasing trend of DCIS in 5-year increments of time (Figure 2, especially in the older age group when all survivors were considered together). This trend in DCIS was not statistically significant after adjusting for therapy exposures and doses (RR, 1.13; 13% increase per 5 years, 95% CI, 0.97-1.32; Table 3). When adjusted for chest RT alone, the trend became statistically significant (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05-1.41). These trends were consistent in survivors of HL. However, in survivors of cancers other than HL, the increased trend of DCIS by 5-year increments of diagnosis era was statistically significant, regardless of whether we accounted for chest RT alone and chest RT as well as anthracyclines and pelvic RT.

Sensitivity analyses considering late recurrence and non–breast cancer SMN as competing-risk events did not change the findings.

Discussion

As the cancer survivor population has grown, the significant risk for treatment-related health outcomes of therapies has become clear.37,38 These findings provide important insight into temporal patterns in treatment-associated breast cancer risk. When we examined the cumulative incidence of breast cancer by age and treatment era, there was no improvement in risk. With the consideration of age at childhood cancer diagnosis and attained age, we observe a significant decline in survivors’ invasive breast cancer incidence rate in more recent treatment eras. We document for the first time, to our knowledge, that this decline remains statistically significant, although slightly attenuated, after accounting for detailed cancer treatment exposures. The decline of the rate was at least in part associated with the diminished use of chest RT (and dose reductions), but the association was tempered by an increased use of anthracyclines. We also observed in women not exposed to chest RT both high doses of anthracyclines and alkylating agents were significantly associated with an increased breast cancer risk. In comparison, among women who had been treated with chest RT the effect of anthracyclines was considerably attenuated and alkylating agents appear to have the opposite effect, decreasing breast cancer risk. Further, we observed a reduction in invasive breast cancer rates among survivors with younger attained ages coupled with a substantial trend of increasing DCIS rates, especially among women exposed to chest RT.

A previous CCSS report39 showed a decline in SMN risk over time associated with reduced RT exposure. However, in a study of SMN risk after HL, Schaapveld and colleagues40 reported that despite radiation field reductions, there was no reduction in cumulative incidence of breast cancer risk by treatment era. When considering all breast cancers, our findings are supportive of those by Schaapveld et al. Yet, when considering age at diagnosis and treatment exposures, we observed invasive breast cancer risk modestly decreasing with time. These trends were also observed when restricting our analyses to HL survivors or only HL survivors treated with chest RT.

These findings suggesting an interaction of high-dose anthracyclines and breast cancer risk in women never exposed to chest RT are consistent with previous reports.17,18,19 In 2 reports17,18 risk was elevated in survivors of sarcoma and leukemia, suggestive of a germline cancer predisposition syndrome. Yet, Ehrhardt and colleagues19 found this association even when controlled for known germline cancer predisposition mutation. Also, consistent with previous observation in women not exposed to chest RT, high-dose alkylators were associated with breast cancer risk. However, in women exposed to chest RT, only low-dose alkylators were protective for DCIS. No alkylator dose category affected the risk of invasive breast cancer in women exposed to chest RT. These findings are consistent in our breast cancer risk prediction model for survivors who were treated with chest RT.41 This study found that although high doses of alkylating agents were associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer, after adjusting for endogenous estrogen exposure, there was no significant association with absolute breast cancer risk.41

In 2003, the Children’s Oncology Group developed guidelines for early breast cancer screening, and other groups followed.42,43 Although our ability to examine screening is limited in this study, we see evidence that early screening may be reducing invasive breast cancer rates. In North America and Europe, screening initiation in the general population ranges from 40 to 50 years. In our study, we observed a large number of breast cancers, including invasive cancers and DCIS cases, diagnosed prior to age 40 years. Moreover, we observed increased DCIS in women exposed to chest RT, reflecting early screening. In the general population, DCIS identification by screening is associated with overscreening; however, in childhood cancer survivors it is critical to improving outcomes. We previously reported that DCIS in survivors was associated with higher rates of mortality than de novo DCIS (77% vs 95% 10-year survival).8 Importantly, although more recent treatment eras were associated with modestly reduced rates of invasive breast cancer in childhood cancer survivors relative to those treated earlier, these rates are not reduced to the extent that breast cancer is no longer a concern. These data, taken in the context of previous studies regarding breast cancer in this population including cost-effectiveness studies,44,45 suggest that early screening still needs to occur, but a more personalized approach may be warranted beyond simply the binary exposure of chest RT.41

Limitations

Our findings should be taken in context of important limitations. With increased screening, our estimates of differences due to changing treatment exposures between decades could be attenuated. Further, patients who were diagnosed in the 1990s have not had the same length of follow-up as earlier treatment decades and many have not reached the age where breast cancer risk increases for the general population. Further, our ability to comprehensively examine all potential risk factors including family history is limited by incomplete data in the CCSS. Whole-exome sequencing is currently being undertaken in a subset of the cohort enabling future exploration of the contributions of genetic risk.46 Detailed data on survivors’ use of exogenous hormones were not available, limiting analysis of the contribution of hormone exposure. Lastly, CCSS does not include collection of treatment data for SMN, limiting our understanding of the role of treatments among those with multiple SMNs.

Conclusions

The findings of this cohort study demonstrate that invasive breast cancer risk in childhood cancer survivors decreased with time in response to adapted RT approaches, though this reduction was tempered by concurrent modification of chemotherapy approaches. We demonstrated high rates of DCIS in younger ages, which may reflect early screening. Future work should couple continued consideration of reduction of exposures associated with known breast cancer risk in up-front childhood cancer clinical trials with examining breast cancer risk associated with therapeutic approaches used after the year 2000 (eg, proton and involved node RT, immunotherapy). These data will be invaluable to minimizing risk while refining risk calculation.

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Female Survivors of Childhood Cancer with Invasive BC and DCIS

eTable 2. Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancers

eTable 3. Treatment exposures for HL survivors and all survivors other than HL

eTable 4. Cumulative incidence (%) for survivors diagnosed 0-9 years of age

eTable 5. Cumulative incidence (%) for survivors diagnosed 10-20 years of age

eTable 6. Cumulative incidence (%) by age for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS

eTable 7. SIRs (95% CI) by age by treatment decade

eFigure 1. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 0-9 years old for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS (A. All childhood cancer survivors; B. All survivors except HL)

eFigure 2. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 10-20 years old for all breast cancers

eFigure 3. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 10-20 years old for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS (A. HL survivors with chest RT; B. All survivors except HL)

eFigure 4. SIRs (95% CI) of all breast cancers by age by treatment decade in all survivors and HL survivors

eFigure 5. SIRs (95% CI) by age by treatment decade in all survivors stratified by exposure to chest radiotherapy

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, et al. Cronin KA (eds.) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2018, National Cancer Institute Bethesda, MD. based on November 2020. SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2021. Accessed June 25, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/

- 2.Williams AM, Liu Q, Bhakta N, et al. Rethinking success in pediatric oncology: beyond 5-year survival. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(20):2227-2231. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):833-842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenney LB, Yasui Y, Inskip PD, et al. Breast cancer after childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;14(8):590-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman DL, Whitton J, Leisenring W, et al. Subsequent neoplasms in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(14):1083-1095. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng AK, Garber JE, Diller LR, et al. Prospective study of the efficacy of breast magnetic resonance imaging and mammographic screening in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2282-2288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tieu MT, Cigsar C, Ahmed S, et al. Breast cancer detection among young survivors of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma with screening magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer. 2014;120(16):2507-2513. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Neglia JP, et al. Mortality after breast cancer among survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2120-2130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SEER Incidence Data . 1975-2018. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/data/

- 10.Inskip PD, Robison LL, Stovall M, et al. Radiation dose and breast cancer risk in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(24):3901-3907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Stovall M, et al. Roles of radiation dose, chemotherapy, and hormonal factors in breast cancer following Hodgkin’s disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(13):971-980. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.13.971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bruin ML, Sparidans J, van’t Veer MB, et al. Breast cancer risk in female survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: lower risk after smaller radiation volumes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4239-4246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson TO, Amsterdam A, Bhatia S, et al. Systematic review: surveillance for breast cancer in women treated with chest radiation for childhood, adolescent, or young adult cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(7):444-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swerdlow AJ, Cooke R, Bates A, et al. Breast cancer risk after supradiaphragmatic radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma in England and Wales: a National Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2745-2752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2217-2223. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark RA, Mostoufi-Moab S, Yasui Y, et al. Predicting acute ovarian failure in female survivors of childhood cancer: a cohort study in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and the St Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE). Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):436-445. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30818-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson TO, Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, et al. Breast cancer risk in childhood cancer survivors without a history of chest radiotherapy: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):910-918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teepen JC, van Leeuwen FE, Tissing WJ, et al. ; DCOG LATER Study Group . Long-term risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms after treatment of childhood cancer in the DCOG LATER Study Cohort: role of chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(20):2288-2298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrhardt MJ, Howell CR, Hale K, et al. Subsequent breast cancer in female childhood cancer survivors in the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(19):1647-1656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elkin EB, Klem ML, Gonzales AM, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of breast cancer in women with and without a history of radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a multi-institutional, matched cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2466-2473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson MM, Neglia JP, Woods WG, et al. Lessons from the past: opportunities to improve childhood cancer survivor care through outcomes investigations of historical therapeutic approaches for pediatric hematological malignancies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(3):334-343. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green DM, Kun LE, Matthay KK, et al. Relevance of historical therapeutic approaches to the contemporary treatment of pediatric solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(7):1083-1094. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donaldson SS, Link MP. Combined modality treatment with low-dose radiation and MOPP chemotherapy for children with Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(5):742-749. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.5.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oeffinger KC, Stratton KL, Hudson MM, et al. Impact of risk-adapted therapy for pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma on risk of long-term morbidity: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(20):2266-2275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien MM, Donaldson SS, Balise RR, Whittemore AS, Link MP. Second malignant neoplasms in survivors of pediatric Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with low-dose radiation and chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1232-1239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salloum E, Doria R, Schubert W, et al. Second solid tumors in patients with Hodgkin’s disease cured after radiation or chemotherapy plus adjuvant low-dose radiation. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2435-2443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koontz BF, Kirkpatrick JP, Clough RW, et al. Combined-modality therapy versus radiotherapy alone for treatment of early-stage Hodgkin’s disease: cure balanced against complications. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):605-611. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow LM, Nathan PC, Hodgson DC, et al. Survival and late effects in children with Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with MOPP/ABV and low-dose, extended-field irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(36):5735-5741. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2308-2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2319-2327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(1):53-67. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(4):229-239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green DM, Liu W, Kutteh WH, et al. Cumulative alkylating agent exposure and semen parameters in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):1215-1223. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70408-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howell RM, Smith SA, Weathers RE, Kry SF, Stovall M. Adaptations to a generalized radiation dose reconstruction methodology for use in epidemiologic studies: an update from the MD Anderson Late Effect Group. Radiat Res. 2019;192(2):169-188. doi: 10.1667/RR15201.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigter LS, Spaander MCW, Aleman BMP, et al. High prevalence of advanced colorectal neoplasia and serrated polyposis syndrome in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer. 2019;125(6):990-999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeger SLLK, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121-130. doi: 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson TM, Mostoufi-Moab S, Stratton KL, et al. Temporal patterns in the risk of chronic health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed 1970-99: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1590-1601. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2569-2582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31610-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turcotte LM, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Temporal trends in treatment and subsequent neoplasm risk among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer, 1970-2015. JAMA. 2017;317(8):814-824. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaapveld M, Aleman BM, van Eggermond AM, et al. Second cancer risk up to 40 years after treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(26):2499-2511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moskowitz CS, Ronckers CM, Chou JF, et al. Development and validation of a breast cancer risk prediction model for childhood cancer survivors treated with chest radiation: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and the Dutch Hodgkin Late Effects and LATER cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(27):3012-3021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV, eds. Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board. Childhood cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. ; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group . American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75-89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furzer J, Tessier L, Hodgson D, et al. Cost-utility of early breast cancer surveillance in survivors of thoracic radiation-treated adolescent Hodgkin lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(1):63-70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeh JM, Lowry KP, Schechter CB, et al. Clinical benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening for survivors of childhood cancer treated with chest radiation: a comparative modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):331-341. doi: 10.7326/M19-3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin N, Wang Z, Liu Q, et al. Pathogenic germline mutations in DNA repair genes in combination with cancer treatment exposures and risk of subsequent neoplasms among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(24):2728-2740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Demographic Characteristics of Female Survivors of Childhood Cancer with Invasive BC and DCIS

eTable 2. Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancers

eTable 3. Treatment exposures for HL survivors and all survivors other than HL

eTable 4. Cumulative incidence (%) for survivors diagnosed 0-9 years of age

eTable 5. Cumulative incidence (%) for survivors diagnosed 10-20 years of age

eTable 6. Cumulative incidence (%) by age for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS

eTable 7. SIRs (95% CI) by age by treatment decade

eFigure 1. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 0-9 years old for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS (A. All childhood cancer survivors; B. All survivors except HL)

eFigure 2. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 10-20 years old for all breast cancers

eFigure 3. Cumulative incidence (%) curves by treatment decade among survivors diagnosed in 10-20 years old for all breast cancers, invasive breast cancer and DCIS (A. HL survivors with chest RT; B. All survivors except HL)

eFigure 4. SIRs (95% CI) of all breast cancers by age by treatment decade in all survivors and HL survivors

eFigure 5. SIRs (95% CI) by age by treatment decade in all survivors stratified by exposure to chest radiotherapy