Abstract

Adhesion molecules, which play a major role in lymphocyte circulation, have not been well characterized in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. T-lymphocyte populations, including CD3, CD4, CD28, and adhesion molecules (L selectin, LFA-1, VLA-4, and ICAM-1) were measured by flow cytometry in a cross-sectional study of 100 HIV-infected and 49 HIV-seronegative adults. HIV-infected adults had lower numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin (P < 0.0001) and VLA-4 (P < 0.01) and higher numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing LFA-1bright (P < 0.002) than did HIV-negative adults. By CD4+-lymphocyte count category (>500, 200 to 500, or <200 cells/μl), HIV-infected adults with more advanced disease had lower percentages of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin and VLA-4 and higher percentages of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing LFA-1. The percentages of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes and of CD3+ L selectin+ lymphocytes were positively correlated (Spearman coefficient = 0.86; P < 0.0001), and the percentage of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes and the CD3+ LFA-1bright lymphocyte/CD3+ LFA-1dim lymphocyte ratio were negatively correlated (Spearman coefficient = −0.92; P <0.00001). The results of this study suggest that HIV infection is associated with altered expression of adhesion molecules.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is characterized by progressive loss of CD4+ lymphocytes, increase in CD8+ lymphocytes, and major functional abnormalities in lymphocyte function (7). Prior to the development of AIDS there is homeostasis of CD3+ lymphocytes, in which CD8+ lymphocytes increase in number to compensate for the loss of CD4+ lymphocytes (16). The later progression of HIV disease is associated with major changes in T-lymphocyte populations, including loss of CD28 surface antigen from both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes (3, 5).

Lymphocyte adhesion molecules include the selectin, integrin, and immunoglobulin gene superfamilies (13, 22). L selectin (CD62L), which plays a major role in lymphocyte recirculation to peripheral lymph nodes, is normally expressed on approximately 70 to 80% of T lymphocytes (23). Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), an integrin which is expressed on virtually all peripheral blood leukocytes, including T lymphocytes, is involved in lymphocyte-endothelial cell adhesion (13). The ligands for LFA-1 are two members of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, intercellular adhesion molecules 1 (ICAM-1) and -2 (ICAM-2). Very late antigen 4 (VLA-4) is expressed on T cells and is involved in lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. The expression of these adhesion molecules during HIV infection is not well understood. We conducted a clinic-based, cross-sectional study of major T-lymphocyte populations and adhesion molecules in HIV-infected adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population consisted of a consecutive sample of HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative adults seen in the outpatient clinics at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Md. The study design was cross-sectional. After written informed consent was obtained, blood samples were collected by venipuncture. All lymphocyte populations were studied from a single blood sample drawn from each subject. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from heparinized blood with Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.), washed in Hanks’ buffered salt solution, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% sodium azide (assay buffer). Conjugated monoclonal antibodies to human CD3, CD4, CD14, CD28, CD45, L selectin (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.), LFA-1, ICAM-1 (AMAC, Westbrook, Maine), and VLA-4 (Endogen, Boston, Mass.) were used in two-color (fluorescein isothiocyanate and phycoerythrin) analyses.

PBMC were prepared according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for leukocyte immunophenotyping in HIV infection (4). One million PBMC were placed in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes, pelleted, and resuspended in 50 μl of assay buffer. The PBMC were stained with combinations of monoclonal antibodies for 20 min at 4°C. All samples were kept at 4°C and in 1% sodium azide throughout the staining process to minimize the likelihood of cell activation. The PBMC were washed twice with 1 ml of assay buffer, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, and analyzed by direct two-color immunofluorescence. Isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies from the same commercial suppliers served as controls for fluorescence marker settings and identification of nonspecific staining.

Flow cytometry was performed by using two-color (FACStar Plus; Becton Dickinson) analysis. Fluorescent microbeads (Simply Cellular and Quantum Simply Cellular beads; Flow Cytometry Standards Corporation, Research Triangle Park, N.C.) were used to calibrate the flow cytometer daily and to control for reproducibility of the assay. For each sample, 20,000 ungated events were collected. The lymphocyte population was selected by backgating for CD45bright CD14− cells from the profile of the sample stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate anti-CD45–phycoerythrin anti-CD14 such that >95% of the forward-scatter versus side-scatter lymphocyte gate was CD45bright and CD14−. Thus, >95% of the lymphocyte gate contained lymphocytes. Quadrant analysis cursors were set from each individual and adjusted from the isotype control sample so that >98% of the gated cells were double negative. Dot plots, histograms, and raw statistical information were generated from this gated lymphocyte population for each analyzed sample. Any shift in population and the presence or absence of dim cells versus bright cells were noted. The raw subset percentage value was divided by the CD45bright CD14−-lymphocyte percentage to correct for nonlymphocyte events in the lymphocyte gate. The CD4+-lymphocyte count was calculated by multiplying the absolute lymphocyte count by the corrected CD4+-lymphocyte percentage from flow cytometric analysis. The absolute lymphocyte count was measured by an automated cell counter (Coulter Diagnostics, Hialeah, Fla.) in the clinical laboratory of Johns Hopkins Hospital. In subjects with large unclassified cells, the lymphocyte count was adjusted after a manual count of a blood smear. Large unclassified cells were included in the calculation of total lymphocytes.

Comparisons of nonparametric data were made between HIV-seronegative and HIV-seropositive individuals by the Mann-Whitney U test. Within the HIV-seropositive group, individuals were divided into strata based upon the number of CD4+ lymphocytes (>500, 200 to 500, and <200 cells/μl). Lymphocyte populations were compared within these three groups by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Analysis of variance was used to examine differences between groups, adjusted by age and sex. The level of statistical significance used in this study was a P value of <0.05. Median and interquartile ranges were used to describe lymphocyte population distributions, since the distributions were asymmetric for most populations.

RESULTS

Expression of adhesion molecules on CD3+ lymphocytes.

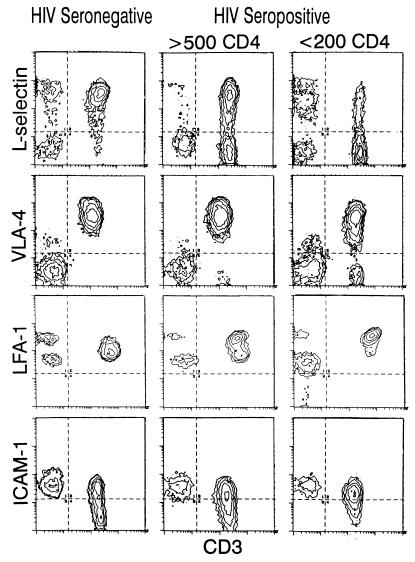

The percentages and absolute counts of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin, VLA-4, LFA-1, and ICAM-1 are shown in Table 1. HIV-seropositive individuals had significantly lower percentages and absolute counts of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin and VLA-4 than did HIV-seronegative individuals. The percentages of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing LFA-1bright and ICAM-1 were significantly higher in HIV-seropositive individuals. There was no significant difference in the absolute numbers of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing ICAM-1 between HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative individuals; however, HIV-seronegative individuals had significantly higher absolute numbers of CD3+ ICAM-1− lymphocytes than did HIV-seropositive individuals. Representative immunofluorescence histograms of adhesion molecules on CD3+ lymphocytes are shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Expression of adhesion molecules on CD3+ lymphocytes

| Marker | CD3+ lymphocytes expressing marker [median (25th-75th percentile)]

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-seronegative adults

|

HIV-seropositive adults

|

|||||||||

| na | No. (cells/μl) | P value | % | P value | na | No. (cells/μl) | P value | % | P value | |

| L selectinhigh | 49 | 1,242 (1,104-1,412) | 0.0001 | 83.1 (78.1-87.2) | 0.0001 | 100 | 513 (219-808) | 0.0001 | 56.1 (47.9-66.7) | 0.0001 |

| L selectinlow | 246 (186-339) | 0.007 | 361 (202-596) | 0.007 | ||||||

| VLA-4+ | 22 | 1,501 (1,371-1,659) | 0.01 | 98.6 (97.8-99.0) | 0.0001 | 23 | 914 (620-1,130) | 0.01 | 93.0 (80.8-96.5) | 0.0001 |

| VLA-4− | 22 (16-33) | 0.005 | 64 (51-88) | 0.005 | ||||||

| LFA-1bright | 49 | 382 (239-538) | 0.002 | 27.6 (15.5-35.3) | 0.0001 | 100 | 616 (296-938) | 0.002 | 65.1 (55.6-77.1) | 0.0001 |

| LFA-1dim | 1,097 (891-1,283) | 0.0001 | 248 (131-472) | 0.0001 | ||||||

| ICAM-1+ | 13 | 547 (336-739) | NSb | 38.3 (25.9-48.7) | 0.05 | 35 | 532 (191-708) | NS | 48.7 (37.4-55.3) | 0.05 |

| ICAM-1− | 882 (732-963) | 0.004 | 491 (296-729) | 0.004 | ||||||

n, number (n) of patients.

NS, not significant.

FIG. 1.

Representative immunofluorescence histograms of adhesion molecules and CD3 expression on lymphocytes from HIV-seronegative and HIV-seropositive individuals. Quadrant settings for the four regions were established such that <2% of positive events in the isotype control sample fell in any positive region.

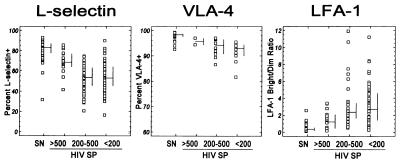

The expression of adhesion molecules on CD3+ lymphocytes was examined according to the CD4+-lymphocyte count (>500, 200 to 500, or <200 cells/μl) among HIV-seropositive individuals (Fig. 2). Lower proportions of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin were found in HIV-seropositive individuals with lower CD4+ lymphocyte counts. The proportion of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing VLA-4 tended to decrease slightly among HIV-seropositive individuals with lower CD4+ counts. With decreasing CD4+-lymphocyte counts among HIV-seropositive adults, the proportions of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing LFA-1 increased.

FIG. 2.

Expression of L selectin, VLA-4, and LFA-1 on CD3+ lymphocytes by HIV status and CD4+-lymphocyte count category. SN, seronegative; HIV SP, HIV seropositive. The bars represent the medians (horizontal) and the 25th and 75th percentiles (vertical).

Expression of CD28+ on T-lymphocyte subsets.

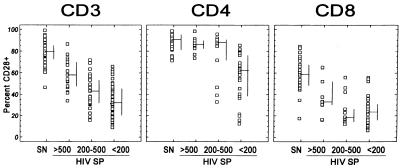

The percentages and absolute counts of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes expressing CD28+ are shown in Table 2. HIV-seropositive individuals had significantly lower absolute counts and percentages of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes expressing CD28+ than did HIV-seronegative individuals. Expression of CD28+ on CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ lymphocytes was examined according to the CD4+-lymphocyte count (>500, 200 to 500, or <200 cells/μl) among HIV-seropositive individuals (Fig. 3). Lower proportions of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing CD28+ were found in HIV-seropositive individuals with lower CD4+ lymphocyte counts. The proportions of CD4+ lymphocytes expressing CD28+ were similar among HIV-seropositive individuals with CD4+ counts of >500 and 200 to 500 cells/μl but were lower among those with CD4+ lymphocyte counts of <200 cells/μl. There was no clear trend for the proportion of CD8+ lymphocytes expressing CD28+ by CD4+ lymphocyte count.

TABLE 2.

Expression of CD28+ on T lymphocyte subsets

| Subset | Cells expressing CD28+ [median (25th-75th percentile)]

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-seronegative adults

|

HIV-seropositive adults

|

|||||||||

| na | No. (cells/μl) | P value | % | P value | na | No. (cells/μl) | P value | % | P value | |

| CD3+ CD28+ | 49 | 1,228 (1,074-1,348) | 0.0001 | 79.7 (72.4-85.6) | 0.0001 | 100 | 377 (155-578) | 0.0001 | 37.9 (29.5-52.7) | 0.0001 |

| CD3+ CD28− | 305 (215-425) | 0.0005 | 492 (245-853) | 0.0005 | ||||||

| CD4+ CD28+ | 27 | 807 (723-1,015) | 0.0001 | 90.6 (81.3-95.3) | 0.0002 | 44 | 66 (17-364) | 0.0001 | 78.6 (58.3-87.3) | 0.0002 |

| CD4+ CD28− | 88 (46-183) | 0.0004 | 26 (13-53) | 0.0004 | ||||||

| CD8+ CD28+ | 27 | 281 (208-357) | 0.002 | 58.5 (48.5-67.5) | 0.0001 | 44 | 156 (91-300) | 0.002 | 23.2 (16.1-33.9) | 0.0001 |

| CD8+ CD28− | 198 (162-252) | 0.0001 | 430 (248-803) | 0.0001 | ||||||

n, number (n) of patients.

FIG. 3.

Expression of CD28+ on CD3+-, CD4+-, and CD8+-lymphocyte subsets by HIV status and CD4+-lymphocyte count category. SN, seronegative; HIV SP, HIV seropositive. The bars represent the medians (horizontal) and the 25th and 75th percentiles (vertical).

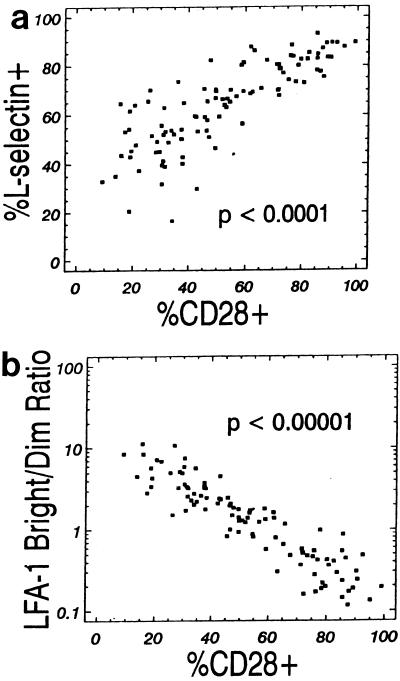

The percentages of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes and CD3+ L selectin+ lymphocytes were positively correlated (Spearman coefficient = 0.86; P < 0.0001), as shown in Fig. 4a. The percentage of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes and the CD3+ LFA-1bright lymphocyte/CD3+ LFA-1dim lymphocyte ratio were negatively correlated (Spearman coefficient = −0.92; P < 0.00001), as shown in Fig. 4b.

FIG. 4.

(a) Percentage of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.86; P < 0.0001). (b) Percentage of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes versus LFA-1bright/LFA-1dim ratio (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.92; P < 0.00001).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that the expression of L selectin and VLA-4 is decreased and the expression of ICAM-1 and LFA-1 is increased on CD3+ lymphocytes during HIV infection. A limitation of the current study is that the use of two-color analysis makes the findings regarding the expression of molecular and activation markers more inferential than if three-color analysis were used. Large unclassified cells were included in the total lymphocyte count. In HIV-infected children, these cells can make up a large proportion of lymphocytes and skew the phenotypic analysis. However, most of the HIV-infected adults did not have a large proportion of large unclassified cells.

The decreased expression of L selectin in both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes has been described in HIV-infected adults (1, 9). In HIV-infected children, a slight decrease in CD4+ CD45RA+ lymphocytes expressing L selectin has been described (18, 19), and CD8+ lymphocytes expressing both L selectin and CD45RA are markedly decreased (20). CD8+ L selectin− lymphocyte counts are elevated in HIV-infected adults and predict progression to AIDS (10). The decreased expression of L selectin on CD3+ lymphocytes suggests that leukocyte rolling along the vascular endothelium and lymphocyte circulation may be impaired during HIV infection.

In this study, HIV-infected individuals had significantly lower percentages and absolute counts of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing VLA-4 than did HIV-seronegative individuals, and advanced HIV infection was associated with a small decrease in CD3+ VLA-4+ lymphocytes. VLA-4 mediates T-cell adhesion to the vascular endothelium via two ligands, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and fibronectin (CS-1 sequence), and VLA-4 also plays a role in T-cell costimulation (21). Relatively little is known about VLA-4 on T lymphocytes during HIV infection.

The percentages of CD3+ lymphocytes expressing ICAM-1 were higher in HIV-infected individuals than in HIV-seronegative individuals in the present study, although the absolute numbers in the two groups were not significantly different. One limitation of the present study was the small sample size of those individuals in which ICAM-1 was measured. ICAM-1 is a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and appears to play a major role in monocyte-lymphocyte communication (15) as well as in the binding of lymphocytes to the vascular endothelium. No differences were noted in the expression of ICAM-1 on monocytes between HIV-infected and HIV-seronegative individuals (15).

Our finding of increased expression of LFA-1 on CD3+ lymphocytes in advanced HIV disease corroborates the findings of previous studies in which LFA-1 expression was upregulated in individuals with more advanced HIV disease (17, 24). Increased LFA-1 expression may facilitate extravasation of CD3+ through the vascular endothelium into tissues during HIV infection. LFA-1 expression is also increased in monocytes during HIV infection (15), and in vitro studies show that there is a twofold increase in LFA-1 expression on HIV-infected monocytes (6). LFA-1 is incorporated into retroviruses from host cells. Increased expression of LFA-1 by CD3+ lymphocytes could also contribute to more efficient virus infection by providing an additional ligand-receptor interaction between cell and virus. Recently it has been demonstrated that monoclonal antibodies to LFA-1 increase plasma neutralization of HIV (11).

The present study corroborates the finding that advanced HIV infection is associated with loss of both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes expressing the CD28 receptor (3, 5). HIV infection of CD4 lymphocytes appears to down-regulate the expression of CD28 (12). The CD28 molecule on CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes interacts with the B7 molecule on antigen-presenting cells to generate signals for the production of interleukin 2 and cell proliferation, and interleukin 2 production appears to be limited to CD8+ CD28+ lymphocytes (2). CD8+ CD28+ lymphocytes appear to play a role in noncytotoxic activity that inhibits HIV replication (14), while CD8+ CD28− lymphocytes have HIV-specific cytotoxic activity (8, 25). There was a high correlation between the percentages of CD3+ L selectin+ and CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes in the present study, suggesting that CD3+ CD28− lymphocytes probably do not express L selectin. The present study showed a negative correlation between the percentages of CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes and CD3+ LFA-1bright/CD3+ LFA-1dim lymphocyte ratio, suggesting that CD3+ CD28+ lymphocytes do not express LFA-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS26643, AI76234, RR00722, HD30042).

We acknowledge the assistance of Marcia Hornsberger, Tish Nance-Sproson, Deneen Esposito, Brian Yost, and Julie Grim in the collection of samples and patient information and thank Joseph Margolick for critical comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bass H Z, Nishanian P, Hardy W D, Mitsuyasu R T, Esmail E, Cumberland W, Fahey J L. Immune changes in HIV-1 infection: significant correlations and differences in serum markers and lymphoid phenotypic antigens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;64:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinchmann J E, Dobloug J H, Heger B H, Haaheim L L, Sannes M, Egeland T. Expression of costimulatory molecule CD28 on T cells in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: functional and clinical correlations. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:730–738. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caruso A, Cantalamessa A, Licenziati S, Peroni L, Prati E, Martinelli F, Canaris A D, Folghera S, Gorla R, Balsari A, et al. Expression of CD28 on CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocytes during HIV infection. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the performance of CD4+ T-cell determinations in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1992;41(RR-8):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choremi-Papadopoulou H, Viglis V, Gargalianos P, Kordossis T, Iniotaki-Theodoraki A, Kosmidis J. Downregulation of CD28 surface antigen on CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes during HIV-1 infection. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhawan S, Weeks B S, Soderland C, Schnaper H W, Toro L A, Asthana S P, Hewlett I K, Stetler-Stevenson W G, Yamada S S, Yamada K M, Meltzer M S. HIV-1 infection alters monocyte interactions with human microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:422–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg M B. Changing the natural history of HIV disease. Lancet. 1996;348:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)06231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorentino S, Dalod M, Olive D, Guillet J G, Gomard E. Predominant involvement of CD8+ CD28− lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic activity. J Virol. 1996;70:2022–2026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2022-2026.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorgi J V, Detels R. T-cell subset alterations in HIV-infected homosexual men: NIAID Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;52:10–18. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgi J V, Liu Z, Hultin L E, Cumberland W G, Hennessey K, Detels R. Elevated levels of CD38+ CD8+ T cells in HIV infection add to the prognostic value of low CD4+ T cell levels: results of 6 years of follow-up. The Los Angeles Center, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:904–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez M B, Hildreth J E. Antibody to adhesion molecule LFA-1 enhances plasma neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:4628–4632. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4628-4632.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffar O K, Smithgall M D, Wong J G, Bradshaw J, Linsley P S. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of CD4′ T cells down-regulates the expression of CD28: effect on T cell activation and cytokine production. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;77:262–270. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hynes R O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signalling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landay A L, Mackewiez C E, Lévy J A. An activated CD8+ T cell phenotype correlates with anti-HIV activity and asymptomatic clinical status. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;69:106–116. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locher C, Vanham G, Kestens L, Kruger M, Ceuppens J L, Vingerhoets J, Gigase P. Expression patterns of Fcγ receptors, HLA-DR and selected adhesion molecules on monocytes from normal and HIV-infected individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:115–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolick J B, Muñoz A, Donnenberg A D, Park L P, Galai N, Giorgi J V, O’Gorman M R, Ferbas J. Failure of T-cell homeostasis preceding AIDS in HIV-1 infection. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Nat Med. 1995;1:674–680. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng T T, Guntermann C, Nye K E, Parkin J M, Anderson J, Norman J E, Morrow W J. Adhesion co-receptor expression and intracellular signalling in HIV disease: implications for immunotherapy. AIDS. 1995;9:337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plaeger-Marshall S, Hultin P, Bertolli J, O’Rourke S, Kobayashi R, Kobayashi A L, Giorgi J V, Bryson Y, Stiehm E R. Activation and differentiation antigens on T cells of healthy, at-risk, and HIV-infected children. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:984–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plaeger-Marshall S, Isacescu V, O’Rourke S, Bertolli J, Bryson Y J, Stiehm E R. T cell activation in pediatric AIDS pathogenesis: three-color immunophenotyping. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;71:19–26. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin R L, Roederer M, Maldonado Y, Petru A, Herzenberg L A, Herzenberg L A. Altered representation of naive and memory CD8 T cell subsets in HIV-infected children. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2054–2060. doi: 10.1172/JCI117891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato T, Tachibana K, Nojima Y, D’Avirro N, Morimoto C. Role of the VLA-4 molecule in T cell costimulation. Identification of the tyrosine phosphorylation pattern induced by the ligation of VLA-4. J Immunol. 1995;155:2938–2947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Springer T A. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tedder T F, Steeber D A, Chen A, Engel P. The selectins: vascular adhesion molecules. FASEB J. 1995;9:866–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermot Desroches C, Rigal D. Leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cell subsets in HIV-1 seropositive patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90138-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vingerhoets J H, Vanham G L, Kestens L L, Penne G G, Colebunders R L, Vandenbruaene M J, Goeman J, Gigase P L, De Boer M, Ceuppens J L. Increased cytolytic T lymphocyte activity and decreased B7 responsiveness are associated with CD28 down-regulation on CD8+ T cells from HIV-infected subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]