Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether spectacle lens sales data can be used to estimate the population distribution of refractive error among patients with ametropia and hence to estimate the current and future risk of vision impairment.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Participants

A total of 141 547 436 spectacle lens sales records from an international European lens manufacturer between 1998 and 2016.

Methods

Anonymized patient spectacle lens sales data, including refractive error information, was provided by a major European spectacle lens manufacturer. Data from the Gutenberg Health Survey was digitized to allow comparison of a representative, population-based sample with the spectacle lens sales data. A bootstrap analysis was completed to assess the comparability of both datasets. The expected level of vision impairment resulting from myopia at 75 years of age was calculated for both datasets using a previously published risk estimation equation combined with a saturation function.

Main Outcome Measures

Comparability of spectacle lens sales data on refractive error with typical population surveys of refractive error and its potential usefulness to predict vision impairment resulting from refractive error.

Results

Equivalent estimates of the population distribution of spherical equivalent refraction can be provided from spectacle lens data within limits. For myopia, the population distribution was equivalent to the Gutenberg Health Survey (≤ 5% deviation) for levels of –2.0 diopters (D) or less, whereas for hyperopia, the distribution was equivalent (≤ 5% deviation) for levels of +3.0 D or more. The estimated rates of vision impairment resulting from myopia were not statistically significantly different (chi-square, 182; degrees of freedom, 169; P = 0.234) between the spectacle lens dataset and Gutenberg Health Survey dataset.

Conclusions

The distribution of refractive error and hence the risk of vision impairment resulting from refractive error within a population can be determined using spectacle lens sales data. Pooling this type of data from multiple industry sources could provide a cost-effective, timely, and globally representative mechanism for monitoring the evolving epidemiologic features of refractive error and associated vision impairment.

Keywords: Astigmatism, Big data, Epidemiology, Hyperopia, Myopia, Refractive error, Vision impairment

Abbreviations and Acronyms: D, diopter; GHS, Gutenberg Health Study; SE, spherical equivalent; SV, single-vision

Vision impairment is an enormous challenge internationally that is projected to worsen as a consequence of global population aging, unless significant effort is made to address the many underlying causes. Refractive error has been identified as a risk factor for the development of numerous ocular pathologies that can lead to vision impairment. Significant refractive errors, both myopic and hyperopic, are known to be amblyogenic in children.1 Higher degrees of hyperopia are a risk factor for the development of age-related macular degeneration,2 whereas higher levels of myopia are known to increase the risk of glaucoma,3 cataract,4 retinal detachment,5 and myopic maculopathy.6

The individual and societal costs of vision impairment are substantial. Societal costs can be measured by the loss of productivity7 and the need to provide adequate medical care and support to those affected by vision impairment.8 Those with vision impairment are more likely to require support in day-to-day living, sustain falls, and experience health or emotional problems that interfere with their lives.8,9 Quality of life is also significantly affected, with vision impairment having a similar impact as stroke, heart attack, and diabetes;10 even mild vision impairment is associated with reduced quality of life.11

Refractive error typically develops in childhood.12 However, the association between refractive error and vision impairment does not become apparent for many decades and is a function of refractive error type and magnitude, as well as increasing age.13, 14, 15 Myopia is the refractive error that is of most concern. It has been demonstrated that an increased lifetime risk of vision impairment accompanies all levels of myopia, but particularly higher levels.13 A recent meta-analysis indicated that 1 in 3 people with high myopia are at risk of bilateral vision impairment within their lifetimes and that even those with low to moderate myopia are at significantly increased risk of ocular disease and disability.16 Evidence is increasing that the prevalence of myopia within the population has increased over the last number of decades. The most significant increases have been observed in Asian populations,17 with some countries seeing more than 90% of children become myopic by the late teenage years.18,19 Although ethnicity seems to play a role, evidence has emerged of increasing prevalence of myopia in many populations around the world.20, 21, 22, 23

It is important to have current and easily accessible refractive error epidemiologic data to plan appropriate public health resource allocation to meet the need for correction of refractive error and treatment of any associated pathologic features, particularly in the context of a changing population burden of refractive error. The landmark article by Holden et al24 predicted that by 2050, almost 50% of the global population will be myopic, with nearly 10% of the population falling into the highly myopic category (using a threshold of –5 diopters [D]). This is of great concern given the likelihood of increased levels of vision impairment resulting from both uncorrected refractive error and the ocular pathologic features associated with myopia. Holden et al24 used existing epidemiologic studies to make their predictions. They identified the lack of epidemiologic data in “many countries and age groups, across representative geographic areas”24 as a significant limitation of their study, with predictions of high myopia prevalence particularly susceptible to the paucity of available evidence. The lack of epidemiologic data is not surprising given the time and financial investment required to carry out these studies.

Because the risk of vision loss associated with increasing refractive error is nonlinear,13,15,16 it is not sufficient to merely establish the proportion of the population affected by myopia or hyperopia. Instead, it is necessary to determine the number of individuals affected by different levels of refractive error within a population to gain a true insight into the population risk of vision impairment resulting from refractive error.

Spectacle lens sales data represent a potential source of contemporary refractive error data that, if made accessible, could provide valuable insights into the changing epidemiologic features of refractive error and associated risks of vision impairment. The value and limitations of spectacle lens sales data as an epidemiologic tool to determine refractive error distribution in a population was described previously.25 Principally, the distribution of refractive error found in spectacle lens sales data does not follow standard population distributions of refractive error because individuals with no refractive error typically do not purchase spectacles lenses; hence, those with emmetropia and near emmetropia are underrepresented in such data. The symptomatic nature of higher levels of refractive error implies that most of those affected are likely to use spectacles, particularly in high-income countries where the visual demands associated with education and employment are high and where subsidized access to eye care is available.26 Most studies of refractive error epidemiologic characteristics report their distributions across the entire range of refractive error. By concentrating analysis on the myopic and hyperopic ends or tails of the distribution, rather than the central emmetropic range of the distribution, it may be possible to use spectacle lens sales data as an epidemiologic tool. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether spectacle lens sales data can be used to estimate the population distribution of refractive error among patients with ametropia and hence to estimate the current and future impact of refractive errors on the risk of vision impairment.

Methods

Anonymized patient spectacle lens sales data were provided by a major European spectacle lens manufacturer. This dataset (n = 141 547 436) comprised lenses that had been manufactured and dispatched after an order was received from an eye care practitioner, with most lenses (> 98%) delivered within Europe. The data were collated into histogram data using the SQLite database engine (Hipp, Wyrick & Company, Inc) and analyzed using the R statistical programming language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The Technological University Dublin Research Ethics Committee approved this study, which adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient level consent was not required due to the nature of the anonymization of the data. The data provided included the spherical power, cylindrical power, and axis of the spectacle prescription, lens design, diameter, laterality (prescribed for right or left eye), and date of manufacture. For lens designs with an addition, this was also specified. The presence of an addition allowed the lenses to be separated into 2 groups, the single-vision (SV) lens group and the addition lens group. The data were validated for missing and malformed data fields, and any lenses with incomplete or invalid data were excluded. The spherical equivalent (SE) power was calculated for each lens.

Data from the Gutenberg Health Study (GHS)27 were extracted by digitizing the published results using Plot Digitiser (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/). The GHS was chosen as a comparison for several reasons. First, the GHS took place in Mainz, Germany, and the manufacturer database reflected almost exclusively European lens sales, with Germany being the largest contributor (approximately 48%). Second, because the spectacle lens data comprised a substantial proportion of reading-addition lenses typically used by older presbyopic adults28 (age typically ≥40–45 years),29 the adult age profile of the GHS (age range, 35–74 years) was comparable.

Myopia and hyperopia were analyzed using the definitions given by the GHS, that is, an SE refractive error of less than –0.50 D being considered myopic and an SE refractive error of more than 0.75 D being considered hyperopic. High myopia was defined as an SE of –6.00 D or less. The International Myopia Institute recommends the adoption of an agreed standard for myopia of –0.50 D or less,30 so results using this criterion are also reported.

To determine confidence intervals of the estimates, a bootstrapping technique was used to generate 1000 new distributions of refractive error from the SV and addition lens data, with each new distribution comprising the same original sample size as the GHS (n = 13 959). Bootstrapping is a statistical technique that involves constructing many samples by randomly drawing sets of observations from a dataset.31,32 These multiple samples can then be used to calculate test statistics and confidence intervals.31,32 The new distributions were constructed using the infer extension package for R software. With this technique, the mean number of cases for each 1-D bin value of SE was calculated along with 95% confidence intervals. This was repeated for both the myopic and hyperopic tails of the distributions, and the results were compared with the GHS distribution of refractive error.

To determine the range of refractive error values over which the bootstrap analysis should take place, the analysis was repeated with different SE starting values, starting at 0 D SE and changing in 1-D steps for both the myopic and hyperopic tails of the distribution. This allowed the deviance between the calculated 95% confidence intervals and the GHS distribution to be determined.

The final fitted bootstrapped distributions that allowed comparison with the GHS were generated. The proportion of each 1-D value of myopia and hyperopia was calculated within the range that was found to match the GHS well. The odds ratio of vision impairment resulting from myopia at each 1-D value of myopia was determined using equation 1, as described by Bullimore et al33 and was modeled on published data and models that relate refractive error and age to vision impairment risk.13,15 Vision impairment was defined as 20/67 (0.3 decimal visual acuity equivalent) or worse, the same definition used by Bullimore et al.33 The odds ratio was converted into vision impairment risk percentage using equation 2. This allowed the expected level of vision impairment by 75 years of age for a sample of 100 000 SV spectacle lens users to be calculated. This was compared with the expected level of vision impairment at 75 years of age over the same range of myopia for participants in the GHS.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Results

The spectacle lens dataset comprised 141.5 million lenses from the manufacturer sales records ranging from 1998 through 2016. Records with incomplete or missing data were excluded, and only years with complete data were included in the analysis. In total, 134.3 million spectacle lenses were included, comprising 84.6 million SV lenses and 49.7 million addition lenses.

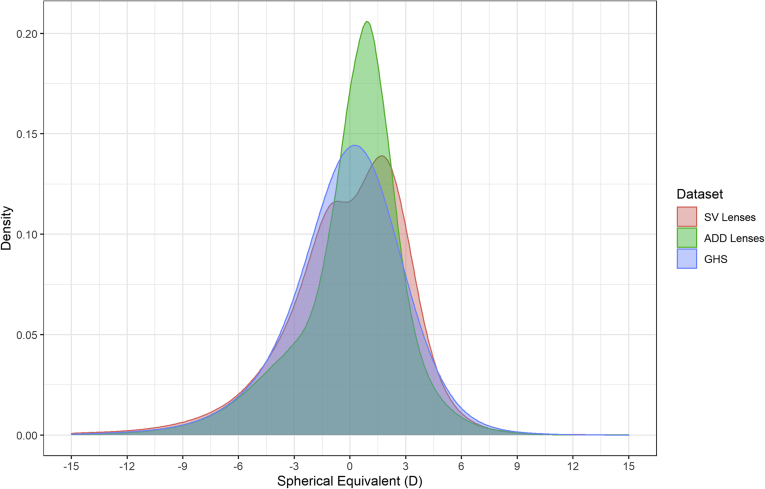

The distributions of refractive error for the SV lenses, addition lenses, and the GHS are shown in Figure 1. All distributions demonstrate the classic negatively skewed leptokurtic curve found in most studies of refractive error, with most observations centered close to emmetropia. The only exception to this pattern was the SV spectacle lenses, which were found to have a bimodal distribution with a significant notch apparent at 0 SE. Table 1 shows the proportion of myopia and hyperopia found in each dataset. The most significant difference observed was in the proportion of emmetropia present, with much lower levels in all spectacle lens datasets.

Figure 1.

The spectacle lens distribution of refractive error from manufacturer data for single-vision (SV) lenses (n = 84 561 994) and addition (ADD) lenses (n = 49 709 191) and from the Gutenberg Health Survey (n = 13 959). D = diopter.

Table 1.

Proportion of Refractive Error Types in Each Dataset

| Total Emmetropia∗ | Total Hyperopia† | Total Myopia‡ | Total Myopia§ | High Myopia|| | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All spectacle lenses | 19.1 | 44.9 | 36.0 | 38.0 | 4.8 |

| SV lenses | 15.5 | 44.9 | 39.6 | 41.7 | 5.3 |

| Addition lenses | 25.0 | 45.1 | 29.9 | 31.9 | 4.0 |

| GHS | 35.1 | 29.8 | 35.1 | 39.9 | 3.5 |

GHS = Gutenberg Health Study; SV = single-vision lenses. Data are presented as percentages.

Spherical equivalent ≥–0.50 diopter and ≤+0.75 diopter.

Spherical equivalent >+0.75 diopter.

Spherical equivalent <–0.50 diopter.

Spherical equivalent ≤–0.50 diopter.

Spherical equivalent ≤–6.00 diopters.

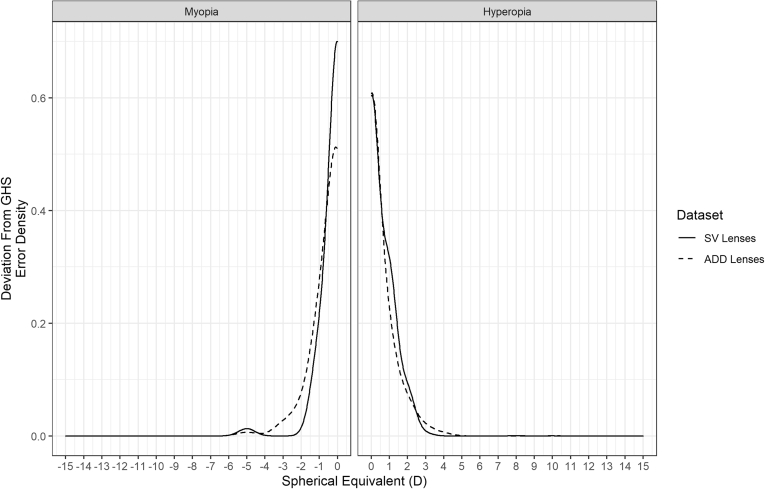

Repeating the bootstrapping technique for both the myopic and hyperopic tails of each distribution, it was found that the deviation between the actual occurrence of each 1-D value of SE for the GHS and all of the spectacle lens data sets was greatest (> 50%) at 0 D SE. The deviation reduced to 5% or less between –2 and –15 D for the myopic end of the distributions and between +3 and +15 D for the hyperopic end of the distributions (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

The deviation between bootstrapped confidence intervals and the observed occurrence of refractive error in the Gutenberg Health Survey (GHS). The deviation is greatest when starting at 0 diopter (D) spherical equivalent and trends toward 0 at higher absolute values of spherical equivalent. ADD = addition; SV = single-vision.

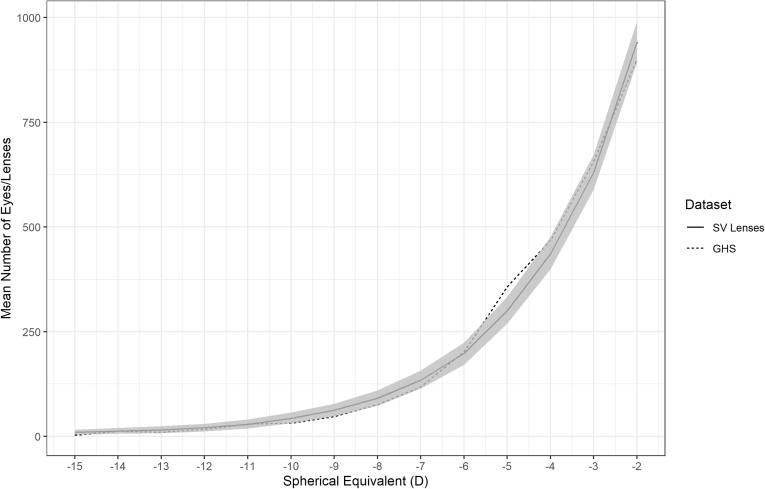

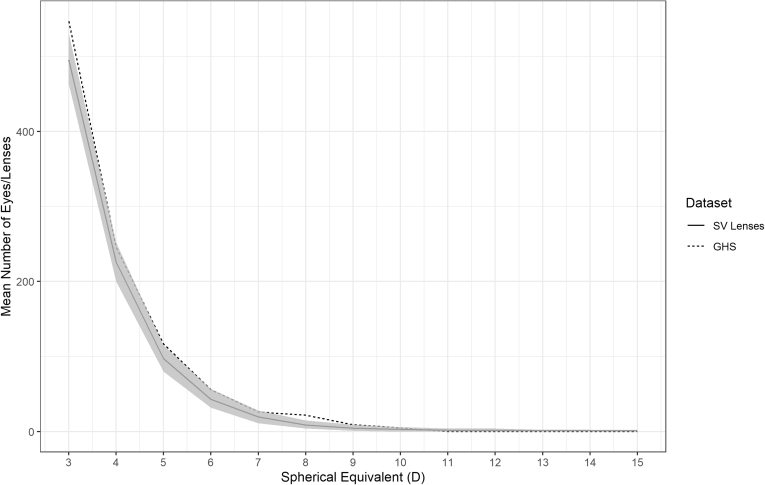

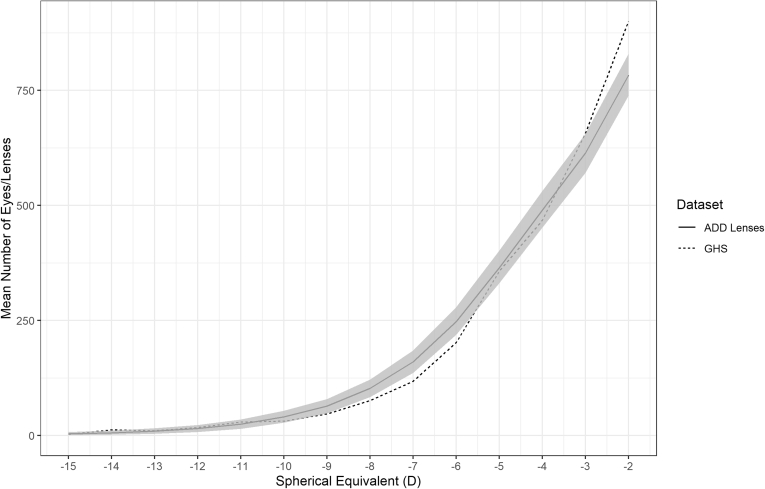

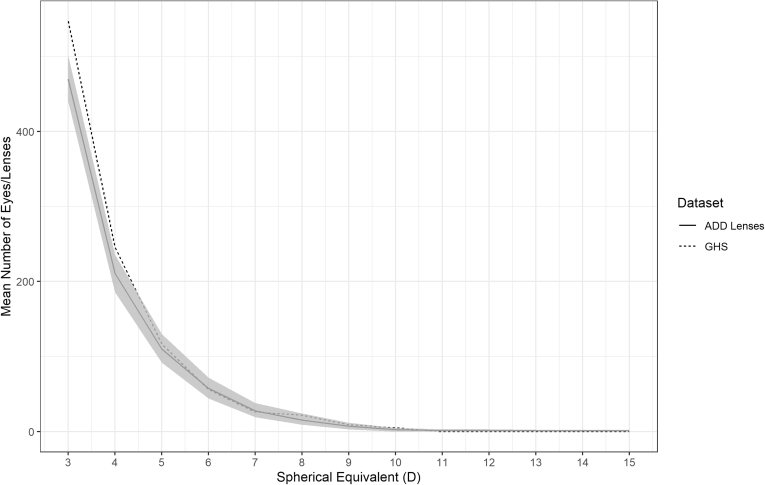

Figures 3 and 4 show the mean number of lenses with 95% confidence intervals for each 1 D from all 1000 generated distributions for the myopic and hyperopic tails of the SV lens distribution over the range of refractive error where the deviation was < 5%. Figures 5 and 6 show the mean number of lenses with 95% confidence intervals for the myopic and hyperopic tails of the addition lens distribution. These are compared with the GHS over the same range of refractive error. The GHS was found to be statistically indistinguishable from the 1000 generated distributions because it mostly sat within the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

The bootstrapped myopic mean distribution with 95% confidence intervals for single-vision (SV) lenses (solid line and shaded area) compared with the Gutenberg Health Survey (GHS; dotted line). D = diopter.

Figure 4.

The bootstrapped hyperopic mean distribution with 95% confidence intervals for single-vision (SV) lenses (solid line and shaded area) compared with the Gutenberg Health Survey (GHS; dotted line). D = diopter.

Figure 5.

The bootstrapped myopic mean distribution with 95% confidence intervals for addition (ADD) lenses (solid line and shaded area) compared with the Gutenberg Health Survey (GHS; dotted line). D = diopter.

Figure 6.

The bootstrapped hyperopic mean distribution with 95% confidence intervals for addition (ADD) lenses (solid line and shaded area) compared with the Gutenberg Health Survey (GHS; dotted line). D = diopter.

Because the tails of the spectacle lens distributions were found to match the GHS between –2 and –15 D and between +3 and +15 D, it was possible to determine the estimated risk of vision impairment at 75 years of age among myopic SV spectacle lens wearers (Table 2). Using the spectacle lens data, it was estimated that 8.18% of myopic spectacle lens wearers (n = 8179 cases per 100 000 population) will be visually impaired by 75 years of age. Over the same range of myopia in the GHS, 7.72% of individuals with myopia (n = 7720 cases per 100 000 population) were estimated to be vision impaired by 75 years of age. The estimated rates of vision impairment were not statistically significantly different (chi-square, 182; degrees of freedom, 169; P = 0.234).

Table 2.

Refractive Distribution within the Myopic Tail of the Single-Vision Spectacle Lens Data and the Gutenberg Health Study Data, Estimated Risk of Vision Impairment at 75 Years of Age from Equations 1 and 2, and Estimated Number of Individuals with Vision Impairment at 75 Years of Age per 100 000 People with Myopia of –2 Diopters or Worse for Both the Single-Vision Lens Group and Gutenberg Health Study

| Spherical Equivalent (D) | Proportion of Myopia in Single-Vision Lenses Group | Proportion of Myopia in Gutenberg Health Study | Risk of Vision Impairment at 75 Years of Age (%) | Estimated No. of Cases of Vision Impairment Resulting from Myopia per 100 000 Population at 75 Years of Age |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectacle Lens Data | Gutenberg Health Study Data | ||||

| –2 | 0.322 | 0.307 | 4 | 1219 | 1164 |

| –3 | 0.215 | 0.224 | 5 | 1067 | 1112 |

| –4 | 0.149 | 0.160 | 6 | 962 | 1032 |

| –5 | 0.102 | 0.122 | 8 | 854 | 1021 |

| –6 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 11 | 733 | 745 |

| –7 | 0.046 | 0.040 | 14 | 634 | 557 |

| –8 | 0.031 | 0.026 | 18 | 548 | 455 |

| –9 | 0.022 | 0.016 | 22 | 472 | 352 |

| –10 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 27 | 402 | 287 |

| –11 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 33 | 330 | 327 |

| –12 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 40 | 285 | 229 |

| –13 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 46 | 248 | 158 |

| –14 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 53 | 225 | 219 |

| –15 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 60 | 200 | 62 |

| Total estimated vision impairment cases per 100 000 population at 75 years of age resulting from myopia of ≤–2.00 D | 8179 | 7720 | |||

D = diopter.

Discussion

This study described a new method to estimate refractive error distribution. For SE refractive errors exceeding +3 D for hyperopia and –2 D for myopia, spectacle lens sales data can provide equivalent estimates of the distribution of refractive error to those determined by conventional population surveys of refractive error. Furthermore, by accurately estimating the shape of the hyperopic and myopic tails of the distribution outside these threshold levels, this approach can provide useful estimates of future population risks of vision impairment.

Some limitations apply with the use of spectacle lens sales data. Those with ametropia may not be corrected with spectacle lenses for numerous reasons, including, for example, lack of access to correction, a leading cause of preventable vision impairment in some parts of the world,34 or the use of alternative forms of correction such as contact lenses. A recent study from the United States indicated that most contact lens wearers also make use of spectacles, however, with only approximately 15% of contact lens wearers reporting they did not own any spectacles and more than 75% reporting their spectacle prescription provided clear vision, indicating that it was up to date.35 It is not certain that European contact lens wearers have the same habits as those in the United States; however, given the widespread availability of spectacles and contact lenses in both regions, it would be surprising if significant differences in spectacle use were found among contact lens wearers. It is also not possible to account for individuals who may have undergone refractive or cataract surgery in the current dataset. However, the literature indicates that although the rates of surgery have increased, they still represent less than 1% of all individuals.36,37 Conversely, some individuals may purchase multiple sets of spectacles; however, given the very large sample size included herein, it is unlikely that these factors would have a significant impact on the results. This is supported by the similar levels of vision impairment predicted using both the spectacle lens data and GHS data. By using multiple datasets, it may be possible to better account for individuals not captured within spectacle lens data. In Europe, statistics are published on the number of surgical procedures performed,38 with similar data available for most countries,39 which may account for those undergoing cataract and refractive surgery. Applying the same methodology to contact lens sales data can account for patients who use only contact lenses for refractive error correction.

Other limitations also apply to the use of industrial-type datasets. Drawing conclusions on subpopulations, for example, can be more difficult because spectacle lens manufacturers and other industry suppliers typically do not record data on their customers’ gender, ethnicity, or age. If these data were to be captured by manufacturers in the future, it could facilitate subpopulation analysis. However, it was previously demonstrated that lenses with a reading addition can be used to estimate a customer’s age.25 Because the relationship between increasing age and increasing refractive error is the primary driver for vision impairment resulting from refractive error,2,13,15 accurate forecasting for the population risk of vision impairment using this methodology should be possible.

Those with emmetropia are also not well represented within these data. This is not surprising because it is unlikely that individuals with minimal or no refractive error purchase spectacle lenses in any significant quantities. This can be observed by the atypical distribution of refractive error for the SV lenses in Figure 1. Another contributing factor to this atypical distribution may be the use of low plus SV lenses as a reading correction by those with emmetropic presbyopia. It was expected that the addition lens data would provide a closer match to the GHS in the emmetropic range because of the similar age profile to the GHS and the near universality of presbyopia over 50 years of age.25 A likely explanation for the deviation of the addition lens data at emmetropia in Figure 2 is the wide availability of over-the-counter reading glasses that can be used by those with emmetropia and low hyperopia, and the ability of those with low myopia to read comfortably when no correction is in place, meaning those in this range of SE are less likely to purchase progressive addition spectacle lenses. The lack of representation of those with approximately emmetropic refractive errors in our data is a significant limitation, but epidemiologic studies are best placed to establish baseline vision impairment risks for those with emmetropia or near emmetropia. In the GHS, the percentage of individuals estimated to be vision impaired by 75 years of age increases by 1.2% to 8.92% if those with myopia of more than –2.00 D SE are included in the calculations, which translates to approximately 9.38% if extrapolated to the SV spectacle lens wearers. Further modeling of the spectacle lens data may allow for more accurate estimates of the proportion of individuals in this low-myopia group, which in turn could allow a full population estimate of vision impairment resulting from myopia to be calculated. From a public health perspective, obtaining the current population burden of those with higher absolute refractive errors, especially myopia, is of particular importance because we are entering an era where myopia can reasonably be considered as a modifiable risk factor for vision impairment. These represent the individuals most at risk of vision impairment resulting from refractive error, and estimating the number of people affected by higher refractive error can allow for better public health planning.40

Because of the nature of the data, it is impossible to state how the refraction for each individual was carried out. Ideally, all refractions are carried out under cycloplegia to avoid the effects of accommodation, particularly for myopic refractions.41 It has been shown that the assessment of refractive error in adults is not significantly affected by the use of cycloplegia,42 particularly in older adults,43 those most at risk of vision impairment. The data used in this study likely represent predominantly adult populations, particularly the addition lens data from which approximate ages can be calculated,25 so the probable lack of cycloplegia should have minimal effect on the refractive error and vision impairment estimations. It should also be noted that many well-regarded population surveys of refractive error do not make use of cycloplegia,44,45 including the main comparison study used herein.27 Additionally, the probable lack of cycloplegia in this study is unlikely to be significant because the higher myopic threshold should reduce the risk of a misclassification error and is the approach suggested by the International Myopia Institute when this risk may apply.30

The comparability of the results obtained from spectacle lens data and a conventional epidemiologic study demonstrates the usefulness of industrial datasets as a public health tool in refractive error and vision impairment. The use of industrial data can potentially address the paucity of epidemiologic data available for both refractive error24 and vision impairment.46 Manufacturers with large market share for spectacle lens sales may have refractive error data that can accurately determine the number of people with ametropia in a population, and hence the risk of vision impairment resulting from refractive error, and myopia in particular.

How this methodology could be best exploited to produce ongoing estimates of the population burden of refractive error and consequential vision impairment needs to be determined. The most significant challenge is gaining access to commercial data for public health purposes. One possible solution would involve the creation of an international consortium of industry, academic, professional, intergovernmental, and nongovernmental organizations and other key stakeholder bodies. This could provide a forum for international collaboration in the form of a big data coalition and could lead to a global myopia observatory of data analytic and data visualization resources that could be used for public health planning, research, commercial, and other uses. In providing the platform to gather and merge disparate sources of industry data, this consortium could provide a readily accessible, current, and globally representative body of resources to monitor the changing epidemiologic characteristics of refractive error and associated eye disease and the impact of new treatments and public health interventions, essentially in real time. Furthermore, these resources would inform health planning decisions, would drive clinical practice reform, would stimulate industrial innovation, and ultimately would lead to better population health.

In conclusion, the distribution of refractive error within a population over a large range of refractive error can be determined using spectacle lens sales data. This provides a good alternative when population-level data on refractive error are either absent or outdated. This is a particularly useful methodology to determine the population burden of higher absolute levels of refractive error, which represents the population cohort most at risk of vision impairment resulting from refractive error. An estimation of the future risk of vision impairment resulting from myopia can also be calculated from such data.

Manuscript no. D-21-00112.

Footnotes

Disclosure(s):

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): A.O.: Employee – Carl Zeiss Vision International GmbH

S.W.: Employee – Carl Zeiss Vision International GmbH

Carl Zeiss Vision International GmbH provided the spectacle lens data used in this study free of charge to the investigator team.

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. The human ethics committees at Technological University Dublin approved the study. All research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient level consent was not required due to the nature of the anonymization of the data.

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Moore, Loughman, Flitcroft

Analysis and interpretation: Moore, Loughman, Butler, Flitcroft

Data collection: Moore, Loughman, Ohlendorf, Wahl, Flitcroft

Obtained funding: N/A; Study was performed as part of the authors' regular employment duties. No additional funding was provided.

Overall responsibility: Moore, Loughman, Flitcroft

References

- 1.Pascual M., Huang J., Maguire M.G., et al. Risk factors for amblyopia in the vision in preschoolers study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:622–629.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanya R., Kawasaki R., Tay W.T., et al. Hyperopic refractive error and shorter axial length are associated with age-related macular degeneration: The Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6247–6252. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong T.Y., Klein B.E.K., Klein R., et al. Refractive errors, intraocular pressure, and glaucoma in a white population. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanthan G.L., Mitchell P., Rochtchina E., et al. Myopia and the long-term incidence of cataract and cataract surgery: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:347–353. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yannuzzi L. Risk factors for idiopathic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashi K., Ohno-Matsui K., Shimada N., et al. Long-term pattern of progression of myopic maculopathy: a natural history study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1595–1611.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith T.S.T., Frick K.D., Holden B.A., et al. Potential lost productivity resulting from the global burden of uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:431–437. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.055673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vu H.T.V., Keeffe J.E., McCarty C.A., Taylor H.R. Impact of unilateral and bilateral vision loss on quality of life. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:360–363. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.047498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamoreux E.L., Chong E., Wang J.J., et al. Visual impairment, causes of vision loss, and falls: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:528–533. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chia E.M., Wang J.J., Rochtchina E., et al. Impact of bilateral visual impairment on health-related quality of life: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:71–76. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finger R.P., Fenwick E., Marella M., et al. The impact of vision impairment on vision-specific quality of life in Germany. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3613–3619. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flitcroft D.I. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:622–660. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tideman J.W.L., Snabel M.C.C., Tedja M.S., et al. Association of axial length with risk of uncorrectable visual impairment for Europeans with myopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1355–1363. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan C.W., Ikram M.K., Cheung C.Y., et al. Refractive errors and age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2058–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leveziel N., Marillet S., Dufour Q., et al. Prevalence of macular complications related to myopia—results of a multicenter evaluation of myopic patients in eye clinics in France. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:e245–e251. doi: 10.1111/aos.14246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haarman A.E.G., Enthoven C.A., Tideman J.W.L., et al. The complications of myopia: a review and meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:49. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.4.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan C., Ramamurthy D., Saw S. Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yotsukura E., Torii H., Inokuchi M., et al. Current prevalence of myopia and association of myopia with environmental factors among schoolchildren in Japan. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen M., Wu A., Zhang L., et al. The increasing prevalence of myopia and high myopia among high school students in Fenghua City, Eastern China: a 15-year population-based survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams K.M., Bertelsen G., Cumberland P., et al. Increasing prevalence of myopia in Europe and the impact of education. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1489–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitale S., Sperduto R.D., Ferris F.L. Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971–1972 and 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1632–1639. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bar Dayan Y., Levin A., Morad Y., et al. The changing prevalence of myopia in young adults: a 13-year series of population-based prevalence surveys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2760–2765. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hrynchak P.K., Mittelstaedt A., Machan C.M., et al. Increase in myopia prevalence in clinic-based populations across a century. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:1331–1341. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holden B.A., Fricke T.R., Wilson D.A., et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore M., Loughman J., Butler J.S., et al. Application of big-data for epidemiological studies of refractive error. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Council of Optometry and Optics Executive Committee. Blue Book 2020 Trends in Optics and Optometry - Comparative Data. European Council of Optometry and Optics. Available at: https://www.ecoo.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ECOO_BlueBook_2021_7.pdf

- 27.Wolfram C., Höhn R., Kottler U., et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in the European adult population: the Gutenberg Health Study (GHS) Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:857–861. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan C.M., Fowler C.W. Analysis of a progressive addition lens population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1989;9:163–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1989.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holden B.A., Fricke T.R., Ho S.M., et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1731–1739. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flitcroft D.I., He M., Jonas J.B., et al. IMI—defining and classifying myopia: a proposed set of standards for clinical and epidemiologic studies. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistics notes: bootstrap resampling methods. BMJ. 2015;350:h2622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter J., Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19:1141–1164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1141::aid-sim479>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bullimore M.A., Ritchey E.R., Shah S., et al. The risks and benefits of myopia control. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1561–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinmetz J.D., Bourne R.R.A., Briant P.S., et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9:e144–e160. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalmers R.L., Wagner H., Kinoshita B., et al. Is purchasing lenses from the prescriber associated with better habits among soft contact lens wearers? Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gollogly H.E., Hodge D.O., Sauver J.L., St., Erie J.C. Increasing incidence of cataract surgery: population-based study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daien V., Le Pape A., Heve D., et al. Incidence and characteristics of cataract surgery in France from 2009 to 2012: a national population study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1633–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eurostat Surgical operations and procedures performed in hospitals by ICD-9-CM source of data. 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database Available at:

- 39.Wang W., Yan W., Fotis K., et al. Cataract surgical rate and socioeconomics: a global study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5872–5881. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruiz-Medrano J., Montero J.A., Flores-Moreno I., et al. Myopic maculopathy: current status and proposal for a new classification and grading system (ATN) Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;69:80–115. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolffsohn J.S., Kollbaum P.S., Berntsen D.A., et al. IMI—clinical myopia control trials and instrumentation report. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M132. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanfilippo P.G., Chu B.S., Bigault O., et al. What is the appropriate age cut-off for cycloplegia in refraction? Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:458–462. doi: 10.1111/aos.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan I.G., Iribarren R., Fotouhi A., Grzybowski A. Cycloplegic refraction is the gold standard for epidemiological studies. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:581–585. doi: 10.1111/aos.12642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vitale S., Ellwein L., Cotch M.F., et al. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111–1119. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rim T.H., Kim S.-H., Lim K.H., et al. Refractive errors in Koreans: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2012. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2016;30:214. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.30.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourne R., Steinmetz J.D., Flaxman S., et al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9:e130–e143. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]