Abstract

When the hunter-gatherers finally started settling down as farmers, infectious diseases started scourging them. The earlier humans could differentiate sporadic diseases like tooth decay, tumors, etc., from the infectious diseases that used to cause outbreaks and epidemics. The earliest comprehension of infectious diseases was primarily based on religious background and myths, but as human knowledge grew, the causes of these diseases were being probed. Similarly, the taxonomy of infectious diseases gradually changed from superstitious prospects, like influenza, signifying disease infliction due to the “influence of stars” to more scientific ones like tuberculosis derived from the word “tuberculum” meaning small swellings seen in postmortem human tissue specimens. From a historical perspective, we identified five categories for the basis of the microbial nomenclature, namely phenotypic characteristics of microbe, disease name, eponym, body site of isolation, and toponym. This review article explores the etymology of common infectious diseases and microorganisms’ nomenclature in a historical context.

Keywords: Etymology, Infectious diseases, Microbial nomenclature, Phenotypic characteristics, Eponym, Toponym

1. Background

Hot, dry winds forever blowing,

Dead men to the grave-yards going:

Constant hearses,

Funeral verses;

Oh! What plagues—there is no knowing! .

(Philip Freneau, Philadelphia, 1793)

There was a time in the history of humankind when infectious diseases used to strike with such ferocities that villages and cities used to be wiped out of human residents. In Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, the emergence of any infectious disease outbreak was accompanied by extensive horror among the masses resulting in abandoning their living abode and running away- favoring the transformation of a local phenomenon into a pandemic. People were utterly oblivious to the underlying cause of those dreadful diseases and even ignorant of their treatment and prevention. The misery is reflected in the above verses of a poem titled “Pestilence,” written in the backdrop of an outbreak of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793.

Etymology is the study of the origin of the word from its roots and its development through times till its present form. The birth of microbiology has its roots in Europe; therefore, the microbes’ nomenclatures are primarily derived from old Greek and Latin languages, and therefore, many science students are oblivious to the true meanings of those names. Thus, this research will not only explain the meanings of the names of infectious diseases and microbes but will also bridge the gap between their nomenclature and pathogenesis, highlighting the untiring work of the scientists who unfolded the mysteries of horrible infectious diseases of the past. In this article, we will endeavor to trace the etymology of the current names of the major infectious diseases and the nomenclature of some medically important microbes from historical perspectives.

2. The etymology of some common infectious diseases’ names

A gradual shift from hunter-gatherers to more settled agriculture living among humans started around 10,000 BCE (Hart-Davis 2012). Living in the settled agriculture communities had definite advantages of livestock domestication, better community protection, more food, etc. Yet, it was also accompanied by hazards of acquisition and spread of infectious diseases. The problem was compounded when the world population started to increase, with the surfacing of glitches like wars, famine, mass migrations, human exploration for new lands, etc., thus, the ground for the spread of infectious diseases was laid down. For example, when sea routes were utilized for trading captive laborers from Africa to New World, there was an exchange of some lethal infectious diseases between those continents and subsequently bartering diseases to Europe with drastic consequences. Diseases like malaria, yellow fever, cholera, plague, and influenza had killed more human beings than the combined casualties of the World Wars and other major battles fought in the history of humankind.

The word disease (dis-ease) is an antonym meaning lack of ease. One disease that has scourged mankind since antiquity is malaria. The name originates from the medieval Italian words mal for bad and aria for air. The Romans had noticed that this disease was more prevalent around the marshlands, believing it to be due to inhalation of the dirty fumes from those swamps (Rawal 2020). However, they were not aware of the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of malaria at that time. Another dreadful disease with very high mortality rates was the plague that had rampaged the world, especially in Europe. It was initially called the Black Death because of the appearance of dark blots on the victims’ skin signifying subcutaneous hemorrhages (Duncan and Scott 2005). In the Middle Ages, the word plague was used for any fast-spreading illness. The word originates from the Latin word Plaga which means Stroke or Wound (Ketchell May 14, 2020). The disease was named perhaps due to the rapidity with which plague used to afflict the human population akin to killing and wounding a large number of soldiers on battlefields in a shorter time.

Influenza has an astrological connection, and the name might have been derived from an Italian phrase influenza coeli meaning the influence of heaven or stars (Strauss 23 June 2014). Another viewpoint states the word Influenza being the precursor of the Latin word “influentia,” which means “To Flow into.” It was believed in Medieval times that an invisible fluid from stars caused disease in the human population (Wickramasinghe 2020). Ancient civilization noted the appearance of comets or other celestial phenomena preceding dreadful diseases like plague or Influenza. Many researchers still debate today that the contagions, suspended in the outer earth atmosphere, are showered on earth in the cosmic dust from the movement of comets/ asteroids/ meteorites, etc. (Wickramasinghe 2010). The modern English word “influence” is also derived from it.

The disease cholera has also caused multiple pandemics with significant morbidity and mortality. Till the nineteenth century, the word cholera was used for any diarrheal disease of humans. This word has its roots in Ancient Greek kholéra from cholē, which means bile, or the phrase cholēdra meaning gutter (Kousoulis 2012). Both words cue profuse diarrhea and bilious vomiting accompanying the illness. The word dysentery is of ancient Greek origin devised by Hippocrates in which dys stands for bad/ abnormal/ difficult and entera for intestines/ bowel. Poliomyelitis is a disease of antiquity, and it derives its name from the Greek word polio, which means grey, myelo for the spinal cord, and itis as a suffix for inflammation. Histopathological changes noted exclusively in the grey matter of the spinal cord was the reason behind this term.

In history, Tuberculosis is associated with the tragic death of famous personalities. On Feb 3rd, 1830, after seeing blood spots during a bout of cough, John Keats said, “That drop of blood is my death warrant. I must die” (Smith 2004); he died of tuberculosis a year later. Known as Romantic disease in the past, tuberculosis was once called phthisis from the Greek word phthoe, which means shriveling of organic matter after exposure to intense heat. This is the clinical presentation of untreated tuberculosis we know today as cachexia. It was also called consumption for the same reason. The word tuberculosis originates from the Latin botanical term tuber, which describes a solid, underground rounded outgrowth from a stem, such as a potato. The word tubercle is from the tuberculum, which is diminutive of the tuber, signifying small swelling, while osis is a suffix describing a disease process (Markel 2012). This reflects the small swellings seen in postmortem specimens of tuberculosis-affected tissues, mainly the lungs of the deceased.

There is perhaps no period in human history devoid of any sexually transmitted infection. Gonorrhea is one of the oldest diseases known to humankind. It was also called Claps due to clapping sensation experienced by the victim of disease during micturition (Jose et al., 2020), or due to the treatment protocol in the pre-antibiotic era when the penis of the patient was used to be clapped between two hands of the physician or slapped against the board to force out the pathological discharge (Wooldridge 2022). Alternate views claim it to be a derivative of the French word clapier, which means brothel. Galen first coined the word gonorrhea, denoting the Greek word gonos for seeds and rhea indicating flow. The urethral discharge in gonorrhea was mistakenly believed to be semen-thought to contain seeds for the future creation of human beings. The word gonad is also derived from gonos which means the organs producing seeds (testes and ovaries).

The records of Dengue fever date back to the Chinese Chin Dynasty around 240–420 CE, when this disease was called “Water Poison,” indicating its relation to flying insects dwelling on water. The word Dengue might have been derived from a Spanish Swahili phrase, “ki denga pepo,” which translates as “Sudden, cramp-like seizure of evil spirit,” (Guzman et al., 2008). Another viewpoint suggests that Dengue fever is a restructured local dialect of the term “Dandy Fever” from Barbados Caribbean islands since the 1800 s (Bardi and Jason 2022), which meant “stiffness and dread of motions” (an important clinical feature of the disease). Table 1 depicts some important infectious disease names with the etymological association.

Table 1.

Major Infectious Diseases’ origin of the name and historical correlation.

| S.No | Disease Name | Word of origin with English meanings | Etymological comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anthrax | The Greek word “anthrax” means Charcoal (Palasiuk and Kolodnytska 2020) | Relates to the color of the scab of skin lesions |

| 2 | Botulism | Medieval Latin “botulus” for Sausage | Food from which the organism was the first isolated (Erbguth and Nauman 2000) |

| 3 | Tetanus | From Romanized Ancient Greek, “tetanos” that means taut | Clinical feature of muscle spasm |

| 4 | Varicella | Latin word “varicella” is diminutive of variola (smallpox) | Smaller skin lesions compared to smallpox |

| 5 | Zoster | Greek “zoster” for belt/ girdle | A belt-like skin lesion is seen in herpes zoster |

| 6 | Diphtheria | Greek “diphthera” means prepared hide or leather (Mansfield et al., 2018) | The leather-like tough membrane formed in the throat |

| 7 | Leprosy | Greek “léprā” stands for scaly skin lesions | Clinical features of the disease |

| 8 | Measles | Middle English “masel” for the little spot | Skin lesions |

| 9 | Mumps | English “Mump” meaning to mutter, or Iceland “mumpa” meaning to “fill mouth too much” (Charles Patrick Davis 2022) | Characteristics articulation sound of the patient likened to talking with a mouth full of potato. |

| 10 | Pertussis | Latin “per” for intensive & “tussis” for cough | Clinical features of the disease |

| 11 | Q fever | English “query fever.” | To replace original epithets like Abattoir Fever to discourage defaming the cattle industry |

| 12 | Rabies | Latin “rabere” (to rage) or Sanskrit “rabhas” (to do violence) (Beran 2017) | Clinical features seen in canines and human cases |

| 13 | Rubella | New Latin “ruber” for red | Color of skin rash |

| 14 | Syphilis | Greek word “syphilus” was first used in 1530 by Italian physician and poet Hieronymus Fracastorius in a poem (Spitzer 1955) | A Greek mythological character of shepherd believed to be the first sufferer of the disease |

| 15 | Trachoma | Greek “trάcuma” that stands for roughness | Pathological changes in eyes mucosa |

| 16 | Typhus | Greek “typhos” means stupor, smoke, blind | Clinical features of the disease |

| 17 | Typhoid | Greek “typhoid” means typhus like | Initially thought to be typhus but later differentiated as a separate entity |

3. Microbial nomenclature and etymological background

The microbial nomenclature follows a binomial system with established laid down rules (Low et al., 2015). The binomial system allows the microbes to be assigned genus names followed by species names and sub-species if there exists one. Viruses are not considered living beings, and they do not follow the binomial system of nomenclature. In our research, we identified five broad categories for the basis of microbial nomenclature. These include Phenotypic characteristics of microbe, disease process/symptoms produced, Eponym (name of scientist/ researcher/ patients), site of isolation, and finally, Toponym (Name of place where the organism was first isolated or identified).

3.1. Phenotypic characteristics of the microbe

3.1.1. Nomenclature based on wet mount appearance of microbes

The development and improvement of the first compound microscope in late 1600 by Antony van Leeuwenhoek opened a new insight into the unseen world of microbes. The enthusiastic scientists started observing everything under the microscope. The initial microscopic observations were primarily focused on the wet mount preparation of various specimens, e.g., drops of ponds, lakes, rainwater, etc. The first fascinating characteristic of tiny living creatures that caught the eyes of the observers was their motility. Early scientists devised a now obsolete term “infusoria” for any minute motile aquatic creatures, and one of its types was a single-celled organism called “monas”. Many microbial names were later coined based on these monads, and some still exist in medicine, e.g., Pseudomonas (False Monas) (Palleroni 2010), Aeromonas (Gas producing Monas), Trichomonas (hairy Monas or scientifically flagellated monas), Stenotrophomonas (Greek steno means narrow, trophos meaning feed and monas; depicting limited feeding range of the organism).

Similarly, Vibrio is derived from the Latin word “vibrare,” which means to vibrate or move rapidly (Dorland 2012). This name is reflective of the rapid shooting star-like motility seen in this genus. The Greek word “akineto,” which means non-motile, was Latinized to “acineto” with a change in Greek “k” to Latin “c” sound in the nomenclature of Acinetobacter (Trüper 1999). Entamoeba is a unicellular organism belonging to phylum protozoa. The name is derived from the Greek word entos, meaning ‘within’ and amoibe, which translates as “change, alteration.” This is the classical description of the parasite, which keeps on changing its shape. The term Entamoeba was coined to differentiate the free-living freshwater amoeba feeding upon algae and plankton from Entamoeba that primarily live inside the living host tissues mainly the intestine (Lakna 2017). Yet another parasite called Acanthamoeba has a different etymological background. The Greek word akantha means spike/thorn which depicts the characteristic thorny appearance of the parasite due to its tapering sub-pseudopodia (Walker et al., 2011).

Two microorganisms belonging to the phylum spirochetes are best visualized by darkfield microscopy. Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, is named from the Greek trepo, signifying to rotate/ to turn and nema, which means thread. This is based upon the thin structure and peculiar rotatory motility of the microbe (Pogliani and Ollhoff 2021). The species name pallidum is from the Latin word pallidus, meaning pale yellow-green. The other spirochete Leptospira interrogans has an interesting reason for its name. Leptos in ancient Greek means fine or thin, whereas spira in Latin translates as the coil. The tight coil of this spirochete is reflected in its name. The species nomenclature interrogans was proposed by Surgeon A. M. Stimson in 1907 due to this organism’s resemblance to the English question mark sign (Stimson 1907).

3.1.2. Nomenclature based on stained smear of pathogen/isolate

Hematoxylin, carmin, aniline dyes were used to stain the prokaryote before Danish physician Dr. Hans Christian Jaochim Gram in 1884 invented Gram Staining (Madani 2003). In 1880, Scottish Surgeon Sir Alexander Ogston observed pus from a patient with a knee abscess under the microscope and identified a microorganism he called Staphylococcus. The Greek word staphyle means a bunch of grapes, and kokkos stands for berry (Licitra 2013) because the staphylococci appear in clusters on stained smears. This conformed to an earlier term, Streptococcus, coined by Austrian surgeon Theodor Billroth in 1877, who observed Streptococci in chains. The Greek word streptos means twisted or chain, and kokkos for berry (Cavaillon and Legout 2022).

Fungi had long been identified by their mycelial structure, and any microbe that showed branching filaments were considered fungus in the past. One example is Mycoplasma, which Louis Pasteur discovered while studying Pleuropneumonia in felines in 1843, calling the causative organism a Pleuropneumonia-like organism. Mycoplasma stands for the Greek word mykes, meaning fungus and plasma (formed or shaped), and was first used by A. B. Frank in 1889 while studying the legume root-nodule organisms. However, Julien Nowak in 1929 used this term for the causative organism of bovine Pleuropneumonia due to its mycelial configuration (Krass and Gardner 1973). Other microbes with similar fallacies include the agents like Mycobacterium (Fungus bacterium), Actinomyces (Ray-fungus), Streptomyces (Chain fungus), etc. The true fungus penicillium borrowed its name from Latin penicillus, which means paintbrush, exactly how it looks under a microscope as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Shows the arrangement of phialides and conidia of penicillium fungus on the right side which looks like a paintbrush shown on the left. The penicillium microscopic picture was taken from the Public Health Image Library CDC (URL: https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=19048)

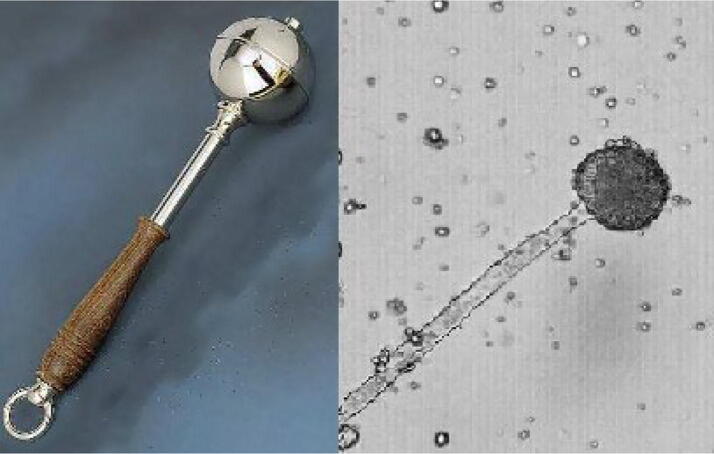

An Italian priest and biologist, Pier Antonio Micheli, named fungus Aspergillus on its resemblance to the aspergillum-a holy water sprinkler (Yu 2010) as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Shows the stalk and the vesicle of Aspergillus fungus on the right side that resembles the holy water sprinkler (aspergillum) on the left side. The picture of aspergillum was taken from the Wikipedia web page (URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aspergillum).

The introduction of Romanowsky and other stains paved the way to the revelation of microorganisms not visible by ordinary Gram staining or wet mount preparation. In 1885, two Italian physicians, Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli, working on malaria, proposed the genus name plasmodium for the causative agent of the disease, the word derived from Late Latin plasma that means mold or formation. The word plasmodium is a botanical term earlier used for the vegetative stage of slime mold of Class Myxomycetes, which appears as a single multi-nucleated cell (Bruce-Chwatt 1987, Britannica February 3, 2010). This resemblance was so striking to the schizont stage of malarial parasites containing multiple merozoites that the term plasmodium was incorrectly adopted and accepted. Similar terminology used for other microbes includes anaplasma from Greek ana for no and plasma for shape, meaning no shape, Toxoplasma from Greek toxon for arc/ bow, and plasma for shape/ form, also pointing towards the bow-shaped tachyzoites. The species falciparum has interesting etymology where Latin falx or falci translates as sickle and parum for like or equal to another (Tiwari and Sinha 2021). This beautifully transcribes the banana-shaped or sickle-shaped gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum seen on Romanowsky stains. The other specie vivax derives its name from the Latin word vīvō meaning to live/to be alive, while -āx (inclined to) is an adjective expression of the verb vīvō. The literal meaning is long-lasting, which hints the longevity of vivax species infection in the host due to its hypnozoites stage causing relapses.

3.1.3. Nomenclature based upon the colonial appearance of the microorganism

Many colonial characteristics were attributed in naming the genus or species of prokaryotes that can grow on artificial culture media. For example, in Staphylococcus aureus, the species name aureus points towards the golden colonies seen on culture medium, and in the Latin language, aurum means gold. Similarly, the species name cereus in Bacillus cereus depicts the waxy colonial appearance of the colonies as cereus in Latin means wax or candle. We are familiar with the word cerumen which is another word for earwax. The colonies of Bacteriodes fragilis demonstrate fragility under certain conditions that led to its species name fragilis.

The scientists studying Proteus were mesmerized by its ability to change shape from small rod to elongated multi-nucleated form teeming with flagella, a characteristic observable on enriched media as swarming strains. The terminology is based upon a Greek mythology character named Proteus who could assume any shape he desired to escape the captor (Armbruster and Mobley 2012). Another interesting phenomenon displayed by prokaryotes is pigment production on the solid enriched culture media. The nomenclature of many bacterial species reflects this trend. For example, the rapid pigment decay in culture medium seen among genus Serratia led to its name marcescens-Latin word meaning decay (Nazzaro 2019). Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces a plethora of pigments on the nutrient agar, but it is most commonly associated with greenish pigment production. The word aeruginosa is derived from the Latin word aerūgō for copper rust and -ōsus added to make adjective of the noun meaning an abundance of copper rust (Talon 2012).

Some microorganisms are named for the biochemical properties of their colonies grown on solid or liquid media. For example, Citrobacter means citrate utilizing rod, species name maltophilia in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia means maltose loving for its maltose fermentation property, another species hydrophila which means water-loving is named due to its propensity to grow in freshwater. The genus Hemophilus in Greek means blood-loving. This name was designated because this bacterium failed to grow on ordinary nutrient agar but grew substantively on medium enriched with blood. The history of the naming of Candida albicans is a fascinating one. The word Candida is borrowed from the Latin word toga candida, which refers to white toga worn by the Roman senators while albicans means to whiten (Vila et al., 2020). Both words essentially denote the white color of the colony of this yeast.

3.1.4. Nomenclature based on electron microscopic appearance of microorganisms

The invention of the first electron microscope in 1931 in Germany paved the way for examining ultra-structures of cells and, more importantly, the study of viruses that were not possible with ordinary compound microscopes. Quite a few viruses were named based on their electron microscopic morphology, e.g., Rotavirus (rota means wheel in modern Latin), Coronavirus in Latin means crown virus for the virus spike proteins resembled the diverging narrow bands seen in the radiant crowns. Similarly, Rhabdoviridae, seen as bullet-shaped in electron microscopy, borrowed its name from the Ancient Greek word rhabdos which means rod. On the other hand, Arenavirus derived its name from Latin arenosus, meaning “sandy,” which reflects the grainy appearance of the ribosomes derived from the host cells. Table 2 depicts some microorganisms’ nomenclature with their microscopic appearances.

Table 2.

Word of origin, meanings, and etymological comments for some common microorganisms’ names based upon microscopic appearance.

| S. No. | Name of microorganism | Word of origin with English meanings | Etymological comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacillus | Diminutive of Latin baculus meaning Little Rod/ wand | The square edges of bacillus look like a wand |

| 2 | Clostridium | Greek klostír for spindle or spinner | Central or subterminal spore gives pathogen a spindle stick appearance |

| 3 | Corynebacterium | Ancient Greek korúnē for club or mace | The resemblance of bacteria to baseball club |

| 4 | Campylobacter | Greek kampulos means bent | Bacilli curved at ends |

| 5 | Helicobacter | Ancient Greek hélix means a spiral shape | The spiral appearance of the bacterium |

| 6 | Chlamydia | Greek khlamys for short mantle | The incorrect assumption that this bacteria cloaks the nucleus of infected cells (Byrne 2003) |

| 7 | Sporothrix | Ancient Greek sporá for seed and thríx for hair | The arrangement of spores along the hyphae likened to seeds along a hair |

| 8 | Cryptococcus | Greek krypto (hidden), kokkos (berry) | The large capsule surrounding the yeast cell |

| 9 | Pneumocystis | Ancient Greek pneúmōn for lungs and kústis for bladder or pouch | The predilection of organisms’ cysts for lung tissues |

| 10 | Cryptosporidium | Greek krypto for hidden and sporidium for small spore | Very small oocysts of parasites usually not visible except Ziehl Neelsen Staining |

3.1.5. Nomenclature based on the gross appearance of the parasites

Most parasites belonging to the phylum Platyhelminthes and Nemathelminthes are visible to the naked eye. The initial naming of these parasites was based upon their gross morphological appearance. For example, Ascaris derived its name from the Greek word askaris, which means intestinal worm, whereas the species name lumbricoides means resembling an earthworm. This was based upon the observation that Ascaris lumbricoides had a striking resemblance to a common soil-dwelling earthworm. One of the hookworms, Ancylostoma, is composed of two words from the ancient Greek language; ankúlos, which means curved/ crooked, and stoma for the mouth. The morphology of this parasite showed a characteristic curved appearance of the mouth part. Trichinella spiralis is another nematode whose name reflects its gross appearance. Trichinella is from the Greek word trichinos, which means made of hair, while -ella is a diminutive suffix. The worm is so tiny that it appears as a very small thread with a naked eye. The species name spiralis is reflective of the curled-up shape of the larval form of this parasite in the muscle tissue of the host.

There are two species of Taenia that have interesting reasoning for their nomenclature. Taenia is from the Greek word tainia, which means tape or ribbon (gross appearance of the parasite) (Viljoen 1937), while the origin of the species name solium might have originated from the French “Solitaire,” which means solitary. When the scientists studied this worm, they observed that on most occasions, an individual is infected with only one specimen of the adult worm at one time (Andrade-Filho, 2011). This led to the naming of this parasite as a solitary tapeworm. When scientists encountered another look-alike species of Taenia, they found it plump, fatter, and larger than the T. solium; hence they named it saginata, which in Latin language means well-fed (Henry 2017). This reflected the naming of the second species of Taenia compared to the earlier discovered T. solium on gross appearance. However, the literature shows that solitary worm infection of humans is not limited to T. solium but can also be seen in T. saginata infestation (Haind Fadel 2022).

The fluke Schistosoma is second only to malaria if we consider the number of individuals it infects and disables worldwide. The adult male, 15–20 mm long, has a gynecophoral canal where the slender female resides. The groove of the gynecophoral canal of the male fluke gives it a mistaken appearance of a split body. This morphological appearance of the adult male is reflected in its name Schistosoma, a name proposed by David Friedrich Weinland in 1858, which comprises two Greek phrases; schistos means split and soma means the body (Di Bella et al., 2018).

3.2. Disease process or symptoms produced

If we closely look at the nomenclature of the microorganism following the binomial system, we will find that many microbes’ species names are the disease names or the symptoms they produce in humans or lower animals. For example, in the case of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Vibrio cholerae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bacillus anthracis, Shigella dysenteriae, Bordetella pertussis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Chlamydia trachomatis, the species name denotes the major diseases the particular microorganism produces (e.g., in above cases, diphtheria, cholera, pneumonia, anthrax, dysentery, pertussis, tuberculosis, trachoma). Few names, however, deserve elucidation and will be discussed in detail.

Streptococcus agalactiae is an important cause of meningitis and pneumonia in the neonatal period and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. During the golden era of microbiology, when every disease was suspected of being caused by unseen microbes, scientists tried to find the etiology of a disease in cattle associated with low milk production. That disease used to involve 15–40 % of the herd with significant losses to the dairy industry in America. A streptococcus was isolated in the lab from the infected cows’ udders, which was named agalactiae; a is prefix meaning no, and galactos mean milk (Chen 2019). This signifies the organism responsible for the absence of milk production in the cattle.

The pre-antibiotic era witnessed many horrific infectious diseases associated with the penetrating wounds inflicted in wars or accidents. One such condition was called gas gangrene, when the infected tissue used to develop gangrene and gas production evident by wound crepitus. When the causative agent was discovered, it was named Clostridium perfringens. The species name perfringens is a Latin epithet that comprises two words: per means through, and frango means to shatter or break in pieces. This was reflective of the histopathological appearance of the gangrenous tissue that displayed coagulative and liquefactive necrosis of the myocytes. Another pathogen that causes rapid fulminant septicemia following wound infection is Vibrio vulnificus. The species name vulnificus is a Latin compound word consisting of two phrases: vulnus, which means a wound, and facere, which translates as to make. Any healthy individual who sustains trauma in seawater develops serious wound infection on exposure to this organism which is the basis of its name.

Entamoeba histolytica is associated with the destruction of the tissue with resultant ulceration or pus formation. The species name histolytica is derived from two Greek words, histos, which translates as tissue, and luein, which means to dissolve. This name is attributed to the lytic properties of this parasite on tissues. Similarly, the species name of Brucella abortus is due to the causation of abortion primarily in cattle. Haemophilus influenzae was named so because it was once thought that this bacterium is the cause of the disease influenza- the species name influenzae in the Greek language means one that causes influenza. The Greek phrase para has many meanings, but in the context of the microbial names, it interprets in the English language as ‘resembling’ or ‘like’ and is used in many microbes’ species names, e.g., parainfluenza (resembling Influenza), parapertussis (resembling pertussis), paratyphoid (typhoid like), paratuberculosis (tuberculosis like), etc. The Greek work para has another connotation in the genus name of the trematode Paragonimus westermani, which signify as ‘nearby/ close to’, while gonimus is from the Greek word gonos which means seeds, and, in this context, the phrase gonimus means fertility organs-testes and ovaries. As testes and ovaries are very close to each other in this parasite, so was the reason for its name.

Herpesviruses are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in human beings, and herpes simplex virus is considered the single most common infectious agent that inflicts humankind today. The word herpes was initially coined for any spreading skin lesion and included conditions like skin cancers, fungal skin infections, bacterial infections like erysipelas, etc. The word herpes is derived from Greek Erpein, which means to creep (Scott 1986). The species name simplex was first used by Daniel Sennert, who classified three types of herpes infections; Herpes simplex, Herpes miliaris, and Herpes exedens, with mild differences in their description (Beswick 1962). He used the term Herpes simplex for skin lesions that ulcerate. The term Herpes simplex survived till today, albeit changing its meaning and description, whereas the others were lost in the dust of times.

Smallpox was one of the most dreadful diseases on the face of the earth that wreaked havoc in humankind since antiquity. The disease name was once considered a death sentence for the victim. The name of the disease still persists in the memories of a small subset of surviving people born before the 1970 s and on the faces of those inflicted by it as pox scars. The word pox means any disease characterized by eruptive sores. The word pox is from the old English word pockes (plural of pocke), which means pustules. The word smallpox was designated to differentiate it from syphilis, called great pox. The causative organism of the smallpox disease is called variola virus, which in the Latin language means pustule and is probably derived from the word Varus which means pimple (Männikkö, 2011b).

The Chickenpox virus was once considered a milder presentation of smallpox. One hypothesis about its terminology suggests that the disease’s milder intensity was probably coward to express itself as smallpox and hence chickenpox. The alternate theory suggests that the old English word for itch was “Giccan,” while in the middle English word, it was called “Icchen” (Sirni 2014). So, the phrase chickenpox might have been derived from these older English words as Giccanpox or Icchenpox. Another assumption is that chickenpox lesions resemble chickpeas and hence derive its name. A similar sonant virus name Chikungunya is usually associated with non-eruptive illness. The word Chikungunya is from Makonde, northern Mozambique, and southeast Tanzania, which translates as “that which bends up.” This reflects the stooped posture resulting from painful arthritis seen in this disease (Schwartz et al., 2014).

3.3. Eponyms

During the golden era of microbiology, there was a practice of specifying the microbes’ nomenclature to the scientist’s name who discovered it or worked on it. There was a race among the scientists to lead the discovery of a causative organism of a particular infectious disease and publish the results in the scientific journal. During a deadly outbreak of plague in June 1894 in Hong Kong, two teams from rival institutes arrived to investigate the cause of the plague. The first to arrive was the Japanese team from Robert Kochs Institute headed by Shibasaburo Kitasato, while the second was the French team from Pasteur Institute led by Alexender Yersin. Despite the government’s full support to the Japanese team, Shibasaburo Kitasato’s work lacked focus. Wrong specimens were drawn for isolation of causative organism, conclusions were drawn in haste, while the description of the causative organism of plague was inaccurate and confusing.

On the other hand, Alexender Yersin focused his work on isolating the organism from the buboes of the deceased patients. His description was correct, comprehensive, and backed by the Pasteur Institute (Butler 2014). However, the isolated organism was initially named Bacterium pestis, changing to Bacillus pestis, then Pasteurella pestis. Finally, the services of Alexender Yersin were acknowledged posthumously, and the bacillus was named Yersinia pestis.

Klebsiella was first described by Carl Friedländer in 1882 in a patient who died of pneumonia, and for a few years, it was called Friedländer’s bacillus. In 1885, Trevisan devised the genus name Klebsiella in honor of German physician Edwin Klebs, who, although did not work on this bacterium, his services in microbiology were great. Edwin Kleb’s main work was related to Corynebacterium diphtheriae which he, along with Friedrich August Johannes Löffler, discovered as the cause of diphtheria. The Corynebacterium diphtheriae was initially called KLB (Klebs Loffler Bacillus).

Dysentery was once a disease of high mortality and considered a disease of war and famine. Genus Shigella is the most important cause of bacillary dysentery. Its discovery is credited to a Japanese physician Kiyoshi Shiga who isolated it from dysentery patients in an epidemic in Japan in the late nineteenth century. Kiyoshi Shiga used the serum of the patient to show that it agglutinated the bacillus isolated from the stool specimen of the same patient but failed to agglutinate with the serum collected from healthy people (Lampel et al., 2018). The organism was later named Shigella dysentery type 1. Simon Flexner, in 1898 isolated a bacillus from dysentery patients in two US Army soldiers, which was similar to the Shiga bacillus, but it failed to agglutinate the serum of Shigella dysentery patients, so this organism was named Flexner’s bacilli and later Shigella flexneri. Subsequently, Carl Sonne in 1915 in Denmark and Major J.S.K. Boyd of the British Royal Army Medical Corps in 1929 in India isolated new species of Shigella that were later named Shigella sonnei and Shigella boydii, respectively.

A German-Austrian pediatrician named Theodor Escherich worked on the infants’ fecal samples and isolated many bacteria. He proposed the name Bacterium coli commune for a motile, Gram-negative gas-producing bacillus. This was later named Escherichia coli (Minodier 2011). He did isolate a bacterium from infants’ stool samples suffering from dysentery but discarded it as a contaminant because those organisms did not produce gas in carbohydrate media. It is speculated that the organism he isolated was most likely Shigella, and had he probed further, one wonders that the name of Shigella might have been Escherichia today.

David Bruce was an Australian-borne British doctor who joined Royal Army Medical Corps in 1884 as a pathologist. When he was stationed at Valletta, Malta, there was an outbreak of fever among British soldiers called Malta fever. He was appointed as the head of the commission to investigate the cause of Malta fever. The commission isolated an organism from the British soldiers that was called Micrococcus melitensis and later Brucella melitensis. The commission also established the link of this bacterium with unpasteurized goat milk. In 1993, he investigated sleeping sickness in Africa and identified Trypanosoma as the cause of illness and tsetse fly as a disease vector. The protozoan was named Trypanosoma brucei after his name.

The first successful launch of a commercial steamboat is credited to Robert Fulton, an American engineer, who in 1807 traveled on his steamboat carrying passengers on Hudson River (Hartenberg 2022). An Italian Monk, Serafino Serrati, in 1795 ran the world’s first steamboat on Arno River, but his scientific discovery was largely ignored in his lifetime. Serratia bacterium was discovered in Italy in 1819. An Italian pharmacist working on the pigment of this bacterium named it Serratia to highlight the world of his countryman’s scientific work on steamboat (Nazzaro 2019).

Table 3 shows the list of eponyms for common microbes.

Table 3.

Eponyms and etymological comments for some common microorganisms.

| S. No. | Microbial nomenclature | Name of Scientist/ Person | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C. fruendii | A. Freund | The species name was credited to microbiologist A. Freund who first discovered the fermentation product trimethylene glycol |

| 2 | Salmonella | Daniel Elmer Salmon | Salmonella was named after USA veterinary doctor Daniel Elmer Salmon for his services in veterinary microbiology. His research assistant Theobald Smith in 1885, first isolated Salmonella choleraesuis. |

| 3 | Burkholderia | Walter Burkholder | Walter Burkholder, a USA plant pathologist, isolated an organism from onion bulb rot disease in 1950, which he named Pseudomonas cepacia, that later was named Burkholderia cepacia. |

| 4 | Acinetobacter baumannii | Prof. Paul and Linda Baumann | Prof. Paul and his wife Linda Baumann first isolated the bacterium in 1968, now called Acinetobacter baumannii. |

| 5 | Bordetella | Jules Bordet | A Belgium immunologist Jules Bordet and his brother-in-law Octave Gengou successfully isolated the bacterium in 1906 from the sputum specimen of his son suffering from whooping cough. |

| 6 | Neisseria | Albert Ludwig Sigesmund Neisser | A German physician working as a dermatologist discovered the causative agent of gonorrhea in 1879. Also, he co-discovered the agent of Leprosy with Gerhard Armauer Hansen |

| 7 | Gardnerella | Hermann L. Gardner | An American bacteriologist isolated this bacterium in 1955 from vaginal samples of women suffering from vaginitis. He named it Hemophilus vaginalis which was later changed to Gardnerella vaginalis in his honor in 1984 |

| 8 | Borrelia burgdorferi | Amédée Borrel & Willy Burgdorfer | Dr. Willy Burgdorfer, an American zoologist/ microbiologist, identified spirochetes in Ixodes ticks and established the cause of Lyme disease in 1982. Amédée Borrel was a French cytopathologist who studied spirochetes and wrote papers on their classification based on morphology. A Dutch bacteriologist named the borrelia genus in 1907 for Amédée Borrel’s work on the classification of spirochetes |

| 9 | Rickettsia prowazekii | Howard Tayler Ricketts, Stanislaus von Prowazek | A Brazilian microbiologist da Rocha-Lima in his publication in 1916, used the term Rickettsia prowazekii to honor the work of American pathologist Howard Taylor Ricketts who died of typhus in 1910 while doing his research, and his colleague Stanislaus von Prowazek who also died of epidemic typhus in 1915 while studying typhus outbreak in Germany prison hospital. |

| 10 | Coxiella burnetii | H.R. Cox, Frank MacFarlane Burnet | Australian virologist Frank MacFarlane Burnet worked on this organism and contracted the illness. He isolated this organism from a patient in 1937, while H.R. Cox, an American bacteriologist, isolated this organism from ticks in 1938. |

| 11 | Epstein-Barr virus | Michael A. Epstein & Y. M. Barr | Michael Anthony Epstein-a British pathologist isolated and grew a virus on cell lines with his Irish coworker Yvonne Barr in 1963 from a sample of a patient with Burkitt lymphoma from Uganda |

| 12 | BK virus | A Sudanese patient | The initials of a 29-year-old patient from which the virus was first isolated in 1971 |

| 13 | JC virus | John Cunningham | The virus was isolated from John Cunningham, suffering from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

| 14 | Sporothrix schenkii | Benjamin Schenck | An American medical student at John Hopkins hospital isolated fungus from a patient’s hand in 1896 |

| 15 | Pneumocystis jirovecii | Prof. Otto Jirovec | A Czechoslovak scientist who, in 1953, first discovered this organism as a cause of pulmonary disease. |

| 16 | Giardia lamblia | Prof. A. Giard & Dr. F. Lambl | Prof. A. Giard was a French biologist who, in 1882, described flagellated protozoa as the cause of common diarrheal illness. Vilém Dušan Lambl was a Czech physician who, in 1859, first published the microscopic drawing of this parasite from the stool sample of a child. |

| 17 | Leishmania donovani | Sir W.B. Leishman & Charles Donovan | A British Royal Army Pathologist, Sir W.B. Leishman, in 1903, while examining spleen specimens of kala-azar patients in India, found oval bodies of protozoa. Similar protozoal structures were also described independently by Charles Donovan in kala-azar patients in India. |

| 18 | Naegleria fowleri | F.P.O. Nägler & Malcolm Fowler | Austrian bacteriologist F.P.O. Nägler first described the life cycle of amoeba passing through the flagellate form. An Australian physician Malcolm Fowler in 1970, first isolated the microbe from the brain tissue of a patient with encephalitis. |

| 19 | Schistosoma mansoni | Sir Patrick Manson | A Scottish physician is credited with describing many infectious parasitic diseases, namely Mansonella perstans, Mansonella ozzardi, Schistosoma mansonii, and many more. |

3.4. Host or body site where microbes are isolated

Historically, there had been a trend to designate a microbe’s genus or more commonly specie name in relation to the host from where it was first isolated or to the body site from where these are regularly found. As an example, the species name of Cryptosporidium hominis signifies that it primarily spread among humans to humans to differentiate from Cryptosporidium parvum that is a zoonosis (Giles et al., 2009). This is in contrast to Toxoplasma gondii, which was first isolated from a rodent Ctendactylus gundi. However, species names of many microbes were designated on the human body anatomical organs from where these are regularly found or cause disease. Examples include Escherichia coli (colon), Ancylostoma duodenale (duodenum), Campylobacter jejuni (jejunum), Helicobacter pylori (pylorus of the stomach), Gardnerella vaginalis, and Trichomonas vaginalis (vagina). In the case of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium, the species name faecalis and faecium both signify feces-the specimen which harbors it most. Strongyloides stercoralis was first isolated from the stool samples of soldiers with diarrhea returning from Vietnam. The Latin word stercus means excrement/ dung, and the name was designated because it was observed in the feces of those infected with this worm.

Staphylococcus epidermitidis is predominantly found on skin epidermis, hence the species’ name. In contrast, the other specie saprophyticus is named so as it was found to be growing on dead and decaying matter. The isolation of Streptococcus pyogenes from the pus specimen resulted in naming this organism. First isolated from onions inflicted by onion rot plant disease, Burkholderia cepacia (onion) was named so (Burkholder 1950), although this organism is an important cause of lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients. One species of Brucella was commonly contracted from pigs, and the organism was named Brucella suis due to this association. A similar association is speculated for calling the organism Taenia solium, where the word solium in the old Latin language also means pig-related. The other etymological association of this parasite is discussed elsewhere in this article.

One organism deserves narration from a historical perspective. Legionella pneumophila was first isolated among patients attending the American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976 (Winn, 1988). The pneumonia outbreak occurred in older soldiers who participated in the convention, and the disease was called a mystery illness at that time. However, the investigations pointed out colonization of cooling towers of the air conditioning system of Bellevue Stratford Hotel by Legionella pneumophila that started the outbreak.

3.5. Toponym

Genus or species names of some microbes are named so in relation to the place from where these were first discovered or geographic location where these microbes were once/ are still endemic. The Vibrio cholerae biotype ElTor was first isolated from the pilgrims returning from Makkah near Al Tur Sinai Egypt in 1905 (Chastel 2007). The new strain was named Vibrio cholerae ElTor because it was a different biotype from the earlier prevalent classic one. Similarly, in 1883, Robert Koch, working in the German Cholera Commission in Egypt, identified a bacterium responsible for Egyptian eye disease (Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis), later named Haemophilus aegyptius. The Latin word aegyptius means “pertaining to Egypt.”

Certain viruses that cause outbreaks are named after the location where these were first isolated. For example, the Zaire Ebolavirus disease was first noticed in an outbreak in Yambuku, Democratic Republic of Congo, in 1976 near a village along the Ebola River. Similarly, in 1947, while researching sylvatic yellow fever disease in Zika forests in Uganda, a virus was accidentally discovered in a febrile rhesus monkey (Gubler et al., 2017). Later, this virus was linked to the outbreak of microencephaly and anencephaly in babies born to pregnant ladies infected with this virus. The virus was named Zika virus after its place of discovery.

The bacteria belonging to the genus Providencia are Gram-negative urease-positive pathogens that are an important cause of urinary tract and healthcare-associated infections. This bacterium was named to delineate Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, United States, where Stuart et al. in 1951 did research on this and related microbes (Charbek 2019). Table 4 enlists toponyms of some common microorganisms with brief etymological descriptions.

Table 4.

Microbial toponyms and brief comments about geographic relationship.

| S. No. | Microbial nomenclature | Geographic location | Brief description of the topographic relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marburg virus | Marburg, Germany | In 1967, an outbreak of viral hemorrhagic fever in Marburg affected 30 individuals, including a veterinarian who had contact with the tissues of a sick monkey (Slenczka and Klenk 2007). |

| 2 | St. Louis Encephalitis virus | St. Louis, Missouri | In 1933, a massive outbreak of encephalitis with high mortality occurred in St. Louis, Missouri, and surrounding counties (Luby 1979). |

| 3 | Coxsackievirus | Coxsackie, New York | While investigating suspected poliomyelitis outbreak, the virus was discovered in 1947 at a small town called Coxsackie on the Hudson River, Greene County, NY |

| 4 | Brucella melitensis | Latin word melitensis means “From Malta” | The species name denotes the place from where the organism was first found, i.e., the island of Malta (Melita) |

| 5 | Francisella tularensis | Tulare, California | In 1911, two researchers discovered the bacterium at Tulare County, California Männikkö, 2011a |

| 6 | Schistosoma japonicum | Japan | This parasite was once endemic in Katayama district, Hiroshima, Japan. Katayama fever was another name for this disease. |

| 7 | Schistosoma mekongi | Mekong river basin | The first case of schistosomiasis was discovered along the Mekong River lower basin stretching from Lao to Cambodia. |

| 8 | Mycobacterium africanum | Africa | A predominant specie that causes almost 40 % of pulmonary tuberculosis cases in West African countries |

| 9 | Mycobacterium kansasii | Kansas | In 1952, the pathogen was first isolated from two patients with chronic tuberculosis-like disease at Kansas City General Hospital, Kansas, Missouri. |

| 10 | Leishmania braziliensis | Brazil | Isolation of Leishmania parasite from patients in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, in 1909 |

| 11 | Trypanosoma brucei Rhodesian | Rhodesia (Zambia) | The specie was isolated in 1909 from the blood of an Englishman in Zambia (“Rhodesia”) (Baker 1995) |

| 12 | Trypanosoma brucei Gambians | Gambia | The specie was isolated from the blood sample of an Englishman in 1901 in the Gambia |

| 13 | Necator americanus | United States | Predominant hookworm disease in the United States |

| 14 | Clonorchis sinensis | Sinensis in Latin means “From China.” | Predominant liver fluke found in China |

| 15 | Brugia malayi | Malay Archipelago | First isolated from the Malay Archipelago, which consists of the world’s largest islands between the Indian ocean and Pacific Ocean (Islands of Indonesia, Philippines, Sumatra, New Guinea, etc.) |

| 16 | Dracunculus medinensis | Related to Madina, KSA | The disease was once endemic in the Holy city of Madina, KSA. |

4. Conclusions

The nomenclature of infectious diseases and their causative microorganisms reflects a continuum of understanding of humankind, from once a mysterious unseen wrath of the demons to a more scientific description of contagions that can be fingerprinted in laboratories today. This metamorphosis of humans’ knowledge from mere superstitions to the current scientific illumination is not of short span but stretches around many millennia or probably the history of humanity itself. The microbes’ names reflect the failure and success stories of the scientists and the efforts they put in to bring forth the hidden world of microbes and save humankind from the horrors of the infectious diseases of the past.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, Majmaah University for supporting this research (Project number R-2022-296).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Andrade-Filho J.d.S. Analogies in medicine: intruder noodles. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2011;53(6):345. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652011000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster C.E., Mobley H.L. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10(11):743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J.R. The subspecific taxonomy of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasite. 1995;2(1):3–12. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1995021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi, A.S., Jason, S., 2022, 17 January 2020. “How Did Dengue Get Its Name? | Think Global Health.” Retrieved 26 April 2022, 2022, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/how-did-dengue-get-its-name.

- Beran G.W. CRC Press; Handbook of zoonoses: 2017. Rabies and infections by rabies-related viruses; pp. 307–357. [Google Scholar]

- Beswick T. The origin and the use of the word herpes. Med. Hist. 1962;6(3):214–232. doi: 10.1017/s002572730002737x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britannica, T. (February 3, 2010). Plasmodium. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Bruce-Chwatt L. Falciparum nomenclature. Parasitology today (Personal ed.) 1987;3(8):252. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder W.H. Sour skin, a bacterial rot. Phytopathology. 1950;40:115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Butler T. Plague history: Yersin’s discovery of the causative bacterium in 1894 enabled, in the subsequent century, scientific progress in understanding the disease and the development of treatments and vaccines. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20(3):202–209. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G.I. Chlamydia uncloaked. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100(14):8040–8042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533181100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaillon J.-M., Legout S. Louis Pasteur: Between Myth and Reality. Biomolecules. 2022;12(4):596. doi: 10.3390/biom12040596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbek, E. (2019, Jul 16, 2019). “Providencia Infections.” Medscape Retrieved 22 March 2022, 2022,, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/226541-overview.

- Chastel C. The centenary of the discovery of the vibrio El Tor (1905) or dubious beginnings of the seventh pandemic of cholera. Histoire des Sciences Médicales. 2007;41(1):71–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.L. Genomic insights into the distribution and evolution of group B streptococcus. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1447. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles Patrick Davis, M. D. P. (2022, 29 March 2021). “Medical Definition of Mumps.” MedicineNet Retrieved 26 April 2022, 2022, from https://www.medicinenet.com/mumps/definition.htm.

- Di Bella S., Riccardi N., Giacobbe D.R., Luzzati R. History of schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) in humans: from Egyptian medical papyri to molecular biology on mummies. Pathogens and global health. 2018;112(5):268–273. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2018.1495357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorland W.A.N. PA, Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2012. Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C.J., Scott S. What caused the Black Death? Postgrad. Med. J. 2005;81:315–320. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbguth F.J., Nauman M. LETTER TO THE EDITOR On the First Systematic Descriptions of Botulism and Botulinum Toxin by Justinus Kerner (1786–1862) Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 2000;9(2):218–220. doi: 10.1076/0964-704X(200008)9:2;1-Y;FT218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles M., Chalmers R., Pritchard G., Elwin K., Mueller-Doblies D., Clifton-Hadley F. Cryptosporidium hominis in a goat and a sheep in the UK. Vet. Rec. 2009;164(1):24. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D.J., Vasilakis N., Musso D. History and Emergence of Zika Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;216(suppl_10):S860–S867. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, M. G., A. B. Perez, O. Fuentes and G. Kouri (2008). Dengue, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. H. K. Heggenhougen. Oxford, Academic Press: 98-119.

- Haind Fadel, M. D. (2022, 5 October 2020). “Taenia saginata.” Microbiology & parasitology Parasites-gastrointestinal (not liver) Retrieved 27 April 2022, 2022, from https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/parasitologytaeniasaginata.html.

- Hart-Davis A. Penguin; 2012. History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. [Google Scholar]

- Hartenberg, R. S. (2022, 20 February 2022). “Robert Fulton | Biography, Inventions, & Facts.” Retrieved 4 May 2022, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Fulton-American-inventor.

- Henry R. Etymologia: Taenia saginata. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23(12):2029. [Google Scholar]

- Jose P.P., Vivekanandan V., Sobhanakumari K. Gonorrhea: Historical outlook. Journal of Skin and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2020;2(2):110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ketchell, M. (May 14, 2020). “Stay alert, infodemic, Black Death: the fascinating origins of pandemic terms.” The Conversation Retrieved 21 July 2021, from https://theconversation.com/stay-alert-infodemic-black-death-the-fascinating-origins-of-pandemic-terms-138543.

- Kousoulis A.A. Etymology of cholera. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18(3):540. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.111636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krass C.J., Gardner M.W. Etymology of the term mycoplasma. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1973;23(1):62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lakna. (2017, 2017-12-13). “Difference Between Amoeba and Entamoeba | Definition, Habitat, Features, Similarities and Differences.” PEDIAA Retrieved 26 April 2022, 2022, from https://pediaa.com/difference-between-amoeba-and-entamoeba/.

- Lampel K.A., Formal S.B., Maurelli A.T. A brief history of Shigella. EcoSal Plus. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0006-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licitra G. Etymologia: Staphylococcus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19(9):1553. [Google Scholar]

- Low N., Stroud K., Lewis D.A., Cassell J.A. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.; 2015. Mind your binomials: a guide to microbial nomenclature and spelling in Sexually Transmitted Infections. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby J.P. St. Louis encephalitis. Epidemiol. Rev. 1979;1(1):55–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani K. Dr. Hans Christian Jaochim Gram: inventor of the Gram stain. Primary Care Update for OB/GYNS. 2003;10(5):235–237. [Google Scholar]

- Männikkö N. Etymologia: Francisella tularensis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17(5):799. [Google Scholar]

- Männikkö N. Etymologia: Variola and Vaccination. Emerging Infectious Disease journal. 2011;17(4):680. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.ET1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield M.J., Sugiman-Marangos S.N., Melnyk R.A., Doxey A.C. Identification of a diphtheria toxin-like gene family beyond the Corynebacterium genus. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(16):2693–2705. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markel, H. (2012). “The Origin Of The Word ‘Tuberculosis’.” Science Friday Retrieved 7/24/2021, 2021, from https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/the-origin-of-the-word-tuberculosis/.

- Minodier P. Escherichia coli [esh”ə-rikʹe-ə coʹlī] Euro Surveill. 2011;16:19815. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro G. Etymologia: Serratia marcescens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25(11):2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palasiuk H., Kolodnytska O. ETYMOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF DEVELOPING FUTURE PHYSICIANS’TERMINOLOGICAL COMPETENCE AS A PEDAGOGICAL PROBLEM. Meдичнa. 2020;ocвiтa(2):103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Palleroni N.J. Wiley Online Library; 2010. The pseudomonas story. [Google Scholar]

- Pogliani F.C., Ollhoff R.D. Etymologia: Treponema. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27(4):1006. [Google Scholar]

- Rawal D. An overview of natural history of the human malaria. Int J Mosq Res. 2020;7(2):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K.L., Giga A., Boggild A.K. Chikungunya fever in Canada: fever and polyarthritis in a returned traveller. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2014;186(10):772–774. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott T.M. Historical Aspects of Herpes Simplex Infections: Part 1. Int. J. Dermatol. 1986;25(1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirni, C. D. (2014). “How Chickenpox got its name.” Today I Found. Feed your brain Retrieved 10/20/2021, 2021, from http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2014/04/chickenpox-got-name/.

- Slenczka W., Klenk H.D. Forty years of Marburg virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196(Supplement_2):S131–S135. doi: 10.1086/520551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. The Strange Case of Mr. Keats's Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38(7):991–993. doi: 10.1086/381980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer L.E.O. THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE TERM “SYPHILIS”. Bull. Hist. Med. 1955;29(3):269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, A. M. (1907). “Note on an organism found in yellow-fever tissue.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970): 541-541.

- Strauss, M. (23 June 2014). “The Craziest Scientific Theory About What Causes Flu Pandemics.” Gizmodo Retrieved July 24 2021, 2021, from https://gizmodo.com/do-flu-viruses-originate-in-outer-space-1594561609.

- Talon D. Etymologia: Pseudomonas. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:1241. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Sinha A. Etymologia: Falciparum. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27(2):470. [Google Scholar]

- Trüper H.G. How to name a prokaryote?: Etymological considerations, proposals and practical advice in prokaryote nomenclature. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1999;23(2):231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Vila T., Sultan A.S., Montelongo-Jauregui D., Jabra-Rizk M.A. Oral candidiasis: a disease of opportunity. Journal of Fungi. 2020;6(1):15. doi: 10.3390/jof6010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, N. F. (1937). “Cysticercosis in swine and bovines, with special reference to South African conditions.”.

- Walker G., Dorrell R.G., Schlacht A., Dacks J.B. Eukaryotic systematics: a user's guide for cell biologists and parasitologists. Parasitology. 2011;138(13):1638–1663. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010001708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe N. Solar Cycle, Maunder Minimum and Pandemic Influenza. Journal of Infectious Diseases & Case Reports SRC/JIDSCR-143. 2020;3 [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe R.J., a. C. Comets and Contagion: Evolution and Diseases From Space. Journal of Cosmology. 2010;7:1750–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Winn W.C., Jr Legionnaires disease: historical perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1988;1(1):60–81. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, A. (2022, 2022-03-07). “Why is Gonorrhea Called the Clap: The History- K Health.” Retrieved 26 April 2022, 2022, from https://khealth.com/learn/std/why-is-gonorrhea-called-the-clap/.

- Yu J.-H. Regulation of development in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycobiology. 2010;38(4):229–237. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.4.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- (26 February 2020). “Monas.” 8 August 2021, from https://species.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Monas&oldid=7405966.

- (2018-09-27). “Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.” VetBact: Veterinary bacteriology: information about important bacteria, 2021-8-9, from https://www.vetbact.org/?artid=159#.