Introduction

Telemental health (TMH) is an equitable, cost-effective, and growing medium for delivering psychosocial and pharmacological treatments to youth and families (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry on Telepsychiatry, 2017; Batastini et al., 2016; Langarizadeh et al., 2017; Myers & Comer, 2016; Myers et al., 2017). The 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic pressured the mental health field to scale up its TMH presence with no plan or infrastructure (Golberstein et al., 2020; Ramtekkar et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). This left many clinicians, with little to no experience with TMH, to learn a new paradigm of treatment delivery “on the fly” with few resources (Scharff et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). As TMH infrastructure expansions will likely remain in place, clinicians must now not only deliver treatments with established clients, but also begin new therapeutic relationships entirely over TMH (Romani et al., 2021; Silver et al., 2020; Weinberg, 2020). Research suggests that relationship building skills can be improved with targeted training (Crits-Cristoph et al., 2006; Karver et al., 2006; Russell et al., 2008; Sotero et al., 2017), and there is a need for clinician-identified training tools (Buckman et al., 2021). Thus, development of a tool that meaningfully distills important recommendations and guidance on how to build and maintain relationships with youth clients over TMH fills a critical gap in the literature.

Building a relationship in psychotherapy is a critical aspect of therapy engagement and the therapeutic alliance, both of which are linked to client and service outcomes (e.g., symptom and diagnostic improvement, cost, satisfaction, Becker et al., 2015, 2018; Karver et al., 2006; Lindsey et al., 2013; McLeod, 2011). While many conceptualizations of the therapeutic relationship exist, this review defines the therapeutic relationship as the socio-emotional bond between a clinician and client, hereafter referred to as the TMH relationship. Building a therapeutic relationship with youth in clinical settings can be a challenge (Campbell & Simmonds, 2011). The shift to TMH complicates relationship-building by adding unique factors into the mix, like navigating technology, novel methods of therapeutic communication (e.g., texting, e-mail), engaging youth from afar, and “Zoom fatigue” (Sanderson et al., 2020; Simpson et al., 2021; Wade et al., 2020; Wiederhold, 2020).

Initial research on the TMH relationship focused on whether or not the TMH relationship can be built, and whether this relationship is equivalent to the in-person relationship (Myers et al., 2017; Simpson & Reid, 2014). An accumulating body of research over the past decade has empirically assessed the nature of the therapeutic relationship in TMH with youth (Baggett et al., 2017; Goldstein & Glueck, 2016; McGill et al., 2017). Investigators have repeatedly found clear evidence that the therapeutic relationship can be built over TMH and that these relationships are largely equivalent to those built in-person (McGill et al., 2017; Sucala et al., 2012). This link holds true regardless of the modality of TMH delivery (i.e., clinician delivering services to a remote site or directly to the client’s home; Baggett et al., 2017; Carpenter et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2013; Germain et al., 2010; Himle et al., 2012; Ricketts et al., 2016).

Efforts have moved past asking the question of “whether” TMH relationships can be built and have advanced to asking “how” TMH relationships can be formed and sustained (e.g., Goldstein & Glueck, 2016). Multiple manuals, empirical papers, reports, and commentaries (hereafter referred to as “works”) have outlined helpful techniques, behaviors, and considerations for building TMH relationships (hereafter referred to as “recommendations”). A number of other works focus on anecdotal or practice-based knowledge, which also hold considerable value (e.g., Myers, 2013). No single guide has systematically reviewed and combined these recommendations, with a focus on TMH with youth and families, into a practical tool for clinicians.

In order to address the need for TMH clinician training tools, this review focuses on two primary aims. First, we aimed to conduct a systematic review of literature that critically informs relationship-building between clinician and youth via TMH. Second, we aimed to distill themes and recommendations found during the systematic review into one cohesive, clinician-friendly training resource (Supplementary Material 1).

Method

Search Strategy

PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science Social Sciences Index were searched on April 14, 2020. The following search strings were used to identify literature published between 2000 and 2020:

videoconferencing psychotherapy OR teletherapy OR telepsychotherapy OR telehealth OR telemental health OR telepsychiatry OR telemedicine OR mhealth OR ehealth AND child OR youth OR teen* or adolescent AND alliance OR relationship OR rapport OR therapeutic relationship

Inclusion Criteria

Relevant rcommendations from outside of the field of psychology and psychiatry were included if they appeared in the review (speech pathology and internal medicine). Works met the following inclusion criteria (a) English language, (b) focused at least in part on youth, (c) included recommendations for building TMH relationships, and (d) were peer-reviewed or edited (e.g., book chapters, technical reports). Studies were not coded for quality; this decision was made because the reviewed documents ranged significantly in terms of scope, methodology, and purpose.

Literature Review

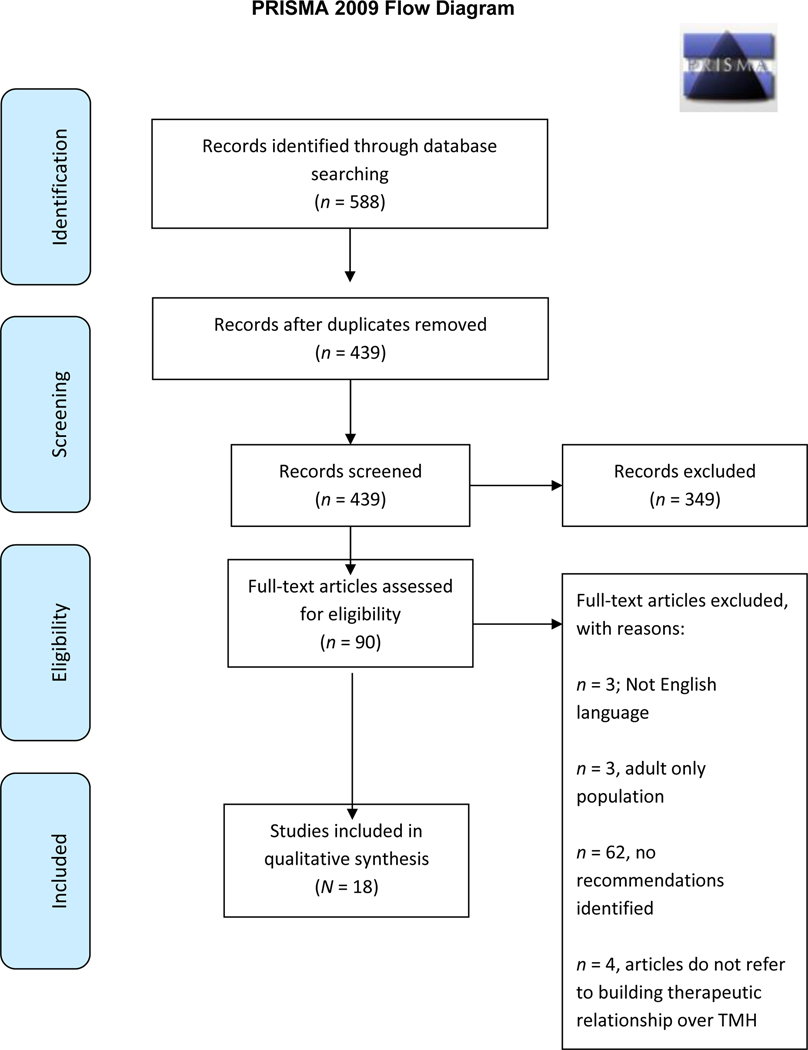

Works were assessed for inclusion by three doctoral-level clinical psychologists: one 31-year-old White Latinx man, one 30-year-old White woman, and one 32-year-old White woman. Three search engines yielded 588 works for review. Of those, 149 were duplicates, leaving 439. Next, Abstrackr (Wallace et al., 2012), an online software, was used to organize and conduct the abstract review. The abstract review excluded 59 articles, leaving 90 for full-text review. Of these 90, 72 were excluded due to not being English language, not focused on youth, or containing no recommendations. The final sample included N = 18 works, denoted by superscript in the reference section. See Figure 1 for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) flow diagram that summarizes inclusion and exclusion decisions.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Coding of Work Characteristics

Articles were single coded by the first author for basic descriptive information, including: Year of publication, publishing journal or book, methodology (quantitative, qualitative, review, or other), discipline (psychology, psychiatry, medicine, speech and language, other), TMH treatment type (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), and delivery modality (provider connecting to client’s home, at a remote site, or no focus on delivery modality, referred to as “multiple/overlapping”).

Recommendation Extraction

Recommendations were extracted and placed into a spreadsheet, with the first author extracting recommendations from 100% of the sample, and the second and third authors each extracting a distinct 50%. Recommendations and corresponding sources were copied verbatim into a spreadsheet (Supplementary Material 2 – Appendix B).

Recommendation Grouping and Distillation

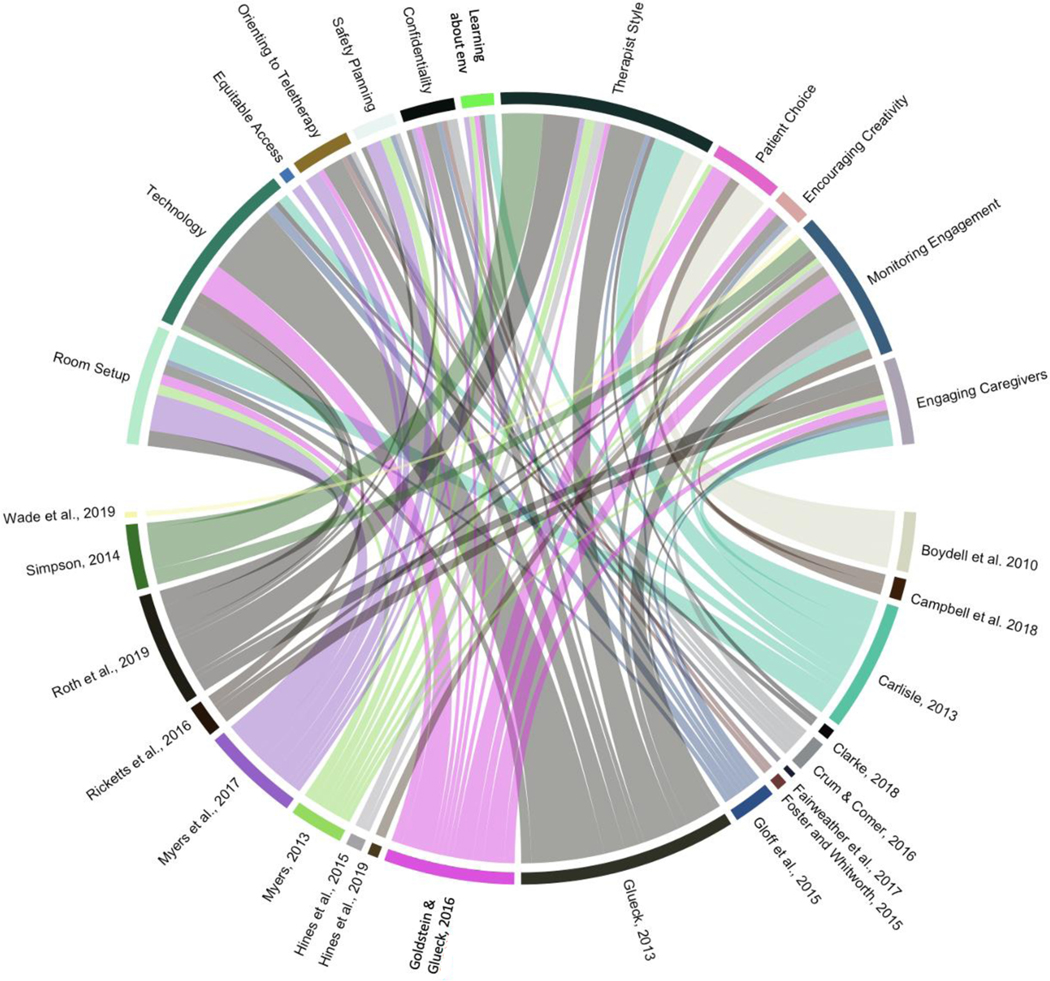

Next, the first author thematically grouped recommendations based upon content (e.g., setting up the room, technology-related considerations). The second and third authors provided consensus feedback on each theme and discussed and resolved disagreements, ensuring that recommendations within themes were concise and thematically similar. All articles contributed to multiple themes (see Figure 2). Figure 2 is a chord diagram (circlize; Gu, 2014; R Core Team, 2020; RStudio Team, 2020), which is a data visualization method used to easily see the connection between the themes and works from which they were distilled. It also provides a practical way to evaluate which themes have received the most attention in the literature.

Figure 2.

Chord Diagram Representing Relation Between Number of Recommendations in Each Theme and Academic Works

Notes. Learning about env = learning about child’s environment

Clinician Guide Creation

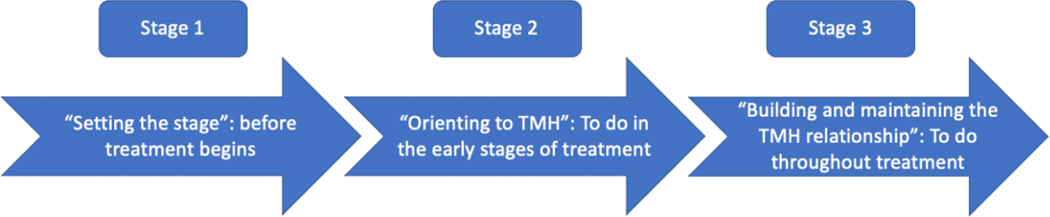

The list of recommendations was distilled using the following methods. First, duplicate recommendations were removed. Authors then rewrote recommendations to avoid plagiarism and increase readability for a clinical audience. Then, each theme was placed into chronological order from intake to termination, using the following stages (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Graphical Representation of the Temporal Model

setting the scene, or actions that should occur prior to beginning a TMH treatment course;

introducing telehealth, or actions to be done in the beginning of a treatment course;

keeping youth engaged, or actions to be done throughout the treatment course.

The resultant list of themes and recommendations were formatted into a visually appealing 10-page document for clinicians (see Supplementary Material 1), using Canva (canva.com), an online graphic design platform, and freely available images from the web-based image repository Unsplash (unsplash.com).

Results

Description of Current Sample

Work Characteristics.

The sample consisted of 18 works which included 195 recommendations. All works were published between 2010–2020, using numerous methodologies: qualitative (n = 5, 27.8%), quantitative (n = 1, 5.6%), mixed-methods (n = 2, 11.1%), reviews (n = 4, 22.2%), book chapters (n = 2, 11.1%), commentaries (n = 2, 5.6%), a case report (n = 1, 5.6%), and a report/guideline document (n = 1, 5.6%). Multiple models of TMH delivery were represented, including: (a) therapy from a provider to a remote site (e.g., school, clinic; n = 3, 16.7%), (b) therapy from a provider to a client’s home (n = 3, 16.7%), (c) psychiatric consultation to a remote site (n = 1, 5.6%), or (d) a lack of emphasis on a specific delivery model (n = 11; 61.1%). Only three works focused on a specific type of therapy (Fairweather et al., 2019; Ricketts et al., 2016; Wade et al., 2019). The most frequently represented discipline was broadly characterized as telemental health (n = 10, 55.6%), with a minority of foci in psychiatry, psychotherapy, speech/language, and telemedicine nursing. A descriptive summary of studies appears in Supplementary Material 2 – Appendix A.

Stages, Themes, and Recommendations

Stage 1: Setting the Scene.

This stage includes recommendations that should be considered and planned prior to the beginning of TMH.

Room Setup.

A number of works (n = 7; 39%) noted the importance of room setup. Recommendations differed slightly based upon the delivery model (e.g., clinician home to remote site versus to client’s house, etc.) but offered consistent themes. At the clinician site, adequate lighting, privacy, and décor were frequently cited as important. At the client’s site (home, classroom, library, or medical examination room), recommendations related to room size, tailoring the layout of the room to the purpose of the session (e.g., structuring a room for an assessment versus a therapy session), and choice of toys and activities (e.g., reducing loud, multi-component toys).

Technology.

Technology was a common theme (n = 8, 44%), including four major technology considerations, including (a) bandwidth, (b) camera, (c) documentation, and (d) microphone.

Bandwidth.

Bandwidth recommendations were consistently set to a minimum of 384 kb/second.

Camera.

Camera placement recommendations differed based upon model delivery. At the clinician’s site, works suggested using the picture-in-picture feature to best understand how a client is observing your environment, and whether anything about the environment is inappropriate or distracting. Works recommended keeping the clinician’s device on a flat surface at eye level, rather than on a clinician’s lap or somewhere with distracting continuous movement. Recommendations for cameras at the client site were similar. If the client camera is able to pan, zoom, and tilt, clinicians can use these features to conduct behavioral observations of the client and caregiver. Cameras should also be placed in a way that best fits the purpose of the assessment; facilitated by collaborating with the client or caregiver.

Documentation.

Documentation practices emerged as important due to the importance of eye contact. Performing documentation during a session, particularly if the clinician’s eyes are diverted from the camera, may make the clinician appear distracted and adversely impact the therapeutic relationship, especially if the client feels that the clinician is not attending to them. If clinicians decide to document during session, works recommend creating a visual array on the clinician’s computer that makes it appear that they are looking into the camera (e.g., aligning the documentation window near the camera). Works also recommended that clinicians use “soft keys,” a digital keyboard that minimizes typing sounds generated by raised keys.

Microphone.

Microphone considerations are important for ensuring clear communication. Recommendations include minimizing or reducing noise by using a noise machine, closing windows/doors to outdoor and common areas, and asking the client if they are hearing feedback or other sounds. Clinicians should perform a test run to assess the clarity of their microphone.

Ensuring Equitable Access.

While not a major focus of the reviewed works (n = 1; 6%), ensuring equitable access to therapy rooms is critical to serve a diverse array of clients if the clinician is connecting with a client at a remote site. Clinicians should assess whether the client has any mobility challenges (e.g., wheelchairs) that will limit the client at the remote site.

Stage 2: Introducing and Orienting Youth to TMH.

Orienting youth and their families to TMH helps generate mutual understanding and expectations between youth and clinicians, contributing to a warm and effective TMH relationship. This stage includes recommendations for introducing TMH and its structure to youth (n = 6; 33%). A developmentally appropriate script may be useful for clinicians’ initial TMH encounter (see Glueck, 2013 for an exceptional example of a script). Recommendations also include providing a logistic and conceptual orientation to TMH and associated utilities (e.g., Zoom, Skype for Business), letting the client and caregivers explore offered features (e.g., learning together how to use a whiteboard feature) with the clinician’s help, continuing to assess and troubleshoot logistical or technological problems, collaborating on a plan for technological failures (e.g., a back-up phone number), discussing the similarities and differences in in-person and TMH treatments, and discussing what treatment will look like overall and week-to-week.

Appropriate Safety Planning.

Clear and appropriate safety planning is a legal and ethical requirement that can have a significant impact on the therapeutic relationship, particularly when expectations about abuse reporting and communication with clients and caregivers were not previously understood (Berk & Clarke, 2019; Klaus et al., 2009). Safety planning was frequently highlighted as an important theme (n = 5, 28%). Recommendations focused upon clear, direct, and continuous communication about safety planning and limits of confidentiality, the necessity of training staff in safety and risk assessment over TMH, creating a plan with caregivers, clients, or staff at a remote site, and researching emergency contacts in the client’s area. Several works recommended that a trustworthy adult be in the same building as youth during any therapy sessions in case safety concerns emerge.

Ensuring Confidentiality and Privacy.

Issues related to confidentiality differ when delivering services into family homes, schools, and other remote sites (DeLuca et al., 2020; Luxton et al., 2011; Myers et al., 2017). Ensuring confidentiality was a major focus of multiple works (n = 7; 39%). It is important to discuss privacy and limits of confidentiality in accord with clinician guidelines and applicable laws with regard to what may or may not be shared, and with whom. At the client’s site, it is important to assess clients’ comfort level with family members overhearing therapy sessions, troubleshoot a more private space, assure clients of their rights to privacy, and disclose whether or not a session will be recorded or if a passive observer will be watching. Encouraging the use of a chat feature and headphones may help address confidentiality and privacy.

Learning About Child’s Environment/Culture.

The environment in TMH can be drastically different than in-person therapy (n = 5, 28%). Understanding a client’s environment and culture is a critical component of evidence-based therapy (Huey & Polo, 2008; Kataoka et al., 2010; Kazak et al., 2010). Further, learning about a client’s intersecting identities can increase understanding of family and client beliefs, customs, and values (Goldstein & Glueck, 2016; Myers, 2013). It is helpful to engage clients, caregivers, and workers at remote sites about ecologically important factors, such as through the use of structured questions (e.g., the Cultural Formulation Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or informal consultation. For instance, youth and families in rural areas are more likely to attempt and complete suicide by firearm than youth from suburban or urban areas (Fontanella et al., 2015; Rivara, 2015). Thus, while it is always important to ask about access to firearms, safety planning with rural families may be more complicated than with a family that has little access to or experience with firearms (see Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee, 2012; Rivara, 2015 for more considerations on this topic). These assessments can inform case conceptualization and treatment planning (see Christon et al., 2015 for a more thorough discussion), and provide fodder to the clinician for engaging youth within their socio-environmental context.

Stage 3: Building Rapport.

This theme refers to clinician behaviors that may facilitate youth and family engagement throughout the TMH treatment course.

Clinician Style.

Clinician style was referenced by a majority of papers (n = 11; 61%), focused on clinician’s use of self-disclosure, formality or attitude, vocal style, eye contact, and reciprocal communication through frequent check-ins. One important and frequent recommendation referred to an increased use of non-verbal communication. TMH can limit the client’s view of the clinician, obfuscating body language. Works recommended an open body posture, increased levels of nonverbal communication (e.g., more expressive affect, hand gestures, or enthusiasm in voice), adjusting the distance of the clinician’s camera using the picture-in-picture function, and an increased emphasis on exploring the client’s changes in body language and non-verbal communication.

Maximizing Client’s Agency.

The importance of providing autonomy, choice, or collaboration was mentioned by four works (22%). These recommendations included clear discussions of informed consent and privacy (so a client can choose to disclose or not disclose information), encouraging use of coping activities that harness their environment (e.g., sitting in a favorite chair), frequently asking about client preferences for therapeutic content, and providing the client with appropriate opportunities to guide treatment (e.g., taking control of a whiteboard or drawing application).

Encourage Creativity/Arts.

The use of expressive arts in the context of evidence-based practice may help to engage youth (Stuckey & Nobel, 2010). Thus, encouraging the use and sharing of creativity and expressive arts was a focus of four works (22%),such as creating and sharing virtual and physical artwork over TMH. This allows clients to demonstrate skills that they value, encourages healthy emotional expression, and fosters a common experience between the client and clinician.

Monitoring and Encouraging Participation.

Half of the reviewed works provided recommendations for monitoring and encouraging engagement (n = 12, 67%). For instance, it may be helpful to check in with clients frequently about whether or not a specific activity is energizing or draining for them, whether they have a preference for any activity, and whether or not they feel comfortable discussing content or engaging in certain activities. It may be helpful to monitor the relationship by administering measures of the therapeutic alliance (e.g., Ardito & Rabellino, 2011; Connors et al., 2020; Scott & Lewis, 2015). It is can also be helpful to integrate aspects of behaviorism and gamification (i.e., engaging and interactive patterns that rely on reinforcement strategies; e.g., Pramana et al., 2018), such that rewards and reinforcers are used to increase and retain engagement (Gosch et al., 2006; Piacentini et al., 2006; Pramana et al., 2018). The creation and use of colorful, engaging, and collaborative handouts and activities (e.g., drawing the cognitive-behavioral triangle together on a virtual whiteboard), may encourage client engagement. Finally, it may be useful to use a client’s favorite online resources as rewards or breaks, such as appropriate music, videos, photos, or game website.

Engaging Caregiver and Family Involvement.

Effectively engaging caregivers and families is a critical piece of TMH, particularly when delivered in the home (n = 7, 39%). Some youth have multiple caregivers, siblings, and extended family in the home during a treatment session (Brown et al., 2020; Myers et al., 2017). Understanding caregivers’ perspectives, engagement, and perceived role in assessment and treatment of youth is necessary for high quality care (Myers et al., 2017). It may be helpful to engage caregivers as models and behavioral managers, coach them in-vivo with parenting skills, and ask about difficult-to-observe behaviors, including tics or eye contact. It is also important to determine when a caregiver should not be present, such as if the caregiver is distracting, distressing, or engaging in treatment-interfering behaviors (e.g., interrupting a trial of exposure with response prevention), and for privacy. It may be helpful to engage a sibling for “in-vivo” coaching of specific skills (e.g., taking a break, relaxation skills). Clinicians should assess and engage those adults who are in a disciplinary or caregiving role with a client (e.g., extended family living in the home). These individuals may have helpful perspectives of behavioral or relational dynamics. Some may be asked to model (e.g., a breathing exercise) or coach (e.g., problem-solving steps) behaviors or skills. Finally, some works suggested that the TMH relationship with caregivers may benefit from more frequent contact (e-mail or phone calls) than is typical in in-person treatment.

Discussion

This paper systematically reviewed a diverse sample of academic works related to building TMH relationships, identified themes, distilled recommendations, and presented a clinician guide for training and supervision purposes. We identified 12 general themes and 195 recommendations. There was good consistency in the recommendations across papers, though no single work identified recommendations from all themes, and no single work included all recommendations included in this review.

In addition to the recommendations gleaned from the literature, clinicians should strive to regularly assess the TMH relationship throughout treatment in order to identify what is and is not working to build the TMH relationship. Available tools for measuring the therapeutic relationship can be completed by multiple informants (Elvins & Green, 2008; McLeod, 2011; Murphy & Hutton, 2018), as the TMH relationship may influence outcomes differentially based upon the informant and type of therapy (Ardito & Rabellino, 2011; Bickman et al., 2012, McLeod, 2011). These ratings can be reviewed and explored in supervision, consultation, or with the client during session as part of a measurement feedback system (Connors et al., 2020; Hawley & Garland, 2008; Scott & Lewis, 2015).

A complete review of tools for measuring the therapeutic relationship is beyond the scope of this review; however, some reviews have compiled relevant measures that can be completed by the clinician and the client (Elvins & Green, 2008; McLeod, 2011; Murphy & Hutton, 2018). This also calls importance to an overall lack of communal resources for clinicians. Hines et al., (2015) specifically discusses the potential for a centralized database with resources for conducting TMH sessions with youth. One such resource is Wikiversity, a crowd-sourcing tool that has collected and summarized logistic and therapy resources to be used in TMH (https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Helping_Give_Away_Psychological_Science/Telepsychology). The authors of this review collaborated with this effort in a recent tip sheet on the topic of building TMH relationships (Kroll et al., 2020; Seager van Dyk et al., 2020; E.A. Youngstrom, personal communication, March 21, 2020) and will submit the peer-reviewed reference to this clinician guide to Wikiversity and ResearchGate in order to disseminate these efforts. Dissemination platforms and crowd-sourcing will be critical in the maintenance of a large TMH workforce.

This review has important considerations for research on TMH. First, researchers may wish to use themes identified in this review to begin identifying and studying the most salient practical aspects of TMH relationship-building. For instance, in the technology theme, it is likely that the TMH relationship would suffer if the internet connection was slower than suggested, but to our knowledge no empirical data confirm this hypothesis. This is important because it is unlikely that all providers and clients have access to similar resources and infrastructure for conducting TMH, especially when considering rurality and urbanicity. The field will need to consider whether specific standards should be placed upon agencies to enforce minimal technology requirements for TMH providers.

Second, measures used to assess the therapeutic relationship need to be psychometrically assessed in the context of TMH and “hybrid” forms of therapy (Lopez & Schwenk, 2021; Mishkind et al., 2020; Mishkind, Shore, & Schneck, 2021). Given that measures of the therapeutic relationship were created with an in-person relationship in mind, re-assessing the psychometric properties of these measures with clients being seen entirely remotely or in a “hybrid” format (i.e., some combination of remote and in-person therapy) will strengthen confidence in these measures and elucidate potential differences in the measurement of therapeutic relationships across these contexts.

Finally, the chord diagram (Figure 3) is a helpful way for researchers to identify areas of TMH that need further study. For instance, research on Learning About Child’s Environment/Culture and Ensuring Equitable Access were rarely discussed in detail, preventing us from distilling practical recommendations. Further research efforts may focus on disseminating widely accessible training resources to help clinicians learn specific questions or areas (e.g., values) of cultural/ecological relevance, such as the cultural formulation interview for DSM-5. There is also a striking lack of studies related to equitable access of TMH services or to perceptions of TMH among underrepresented or minoritized youth (i.e., Black, Indigenous, youth of color, gender and sexual minority youth, neurodivergent youth, or youth with disabilities; e.g., Craig et al., 2021). Some examples exist in the adult literature (George et al., 2012). Future research may, for example, investigate the impact of using the closed captioning feature accessible in some telehealth platforms for youth with hearing loss.

Though telehealth formats are often touted as a way to increase access to care (Menon & Belcher, 2020), reliance on expensive technology and high-speed internet may, in part, widen gaps in access (Darrat et al., 2021; Lame et al., 2021). To advance toward truly equitable access to care, research and policy should focus on youth with inconsistent or no access to wireless internet and/or telehealth-capable technologies (e.g., smart phone), a lack of housing or housing that does not allow for privacy, and other socioeconomic barriers (Valenzuela et al., 2020). While some regulations may be placed on practices (e.g., minimum internet speed), the field must turn its attention to how to reach—and engage—frequently overlooked youth with significant access barriers.

A significant limitation of this review is that relationship-building methods in and of themselves have rarely been empirically tested. This review also did not assess the quality of empirical works, as the heterogeneity of the sample did not allow for such comparison. Additionally, the identified themes were grouped based upon practicality, and it is likely the case that some recommendations could have been placed into multiple themes. A future review could use a Q-sort or modified Delphi procedure to begin distilling the basic practice elements of building TMH relationships (see Becker et al., 2015; Chorpita et al., 2005; Garland et al., 2008; McLeod et al., 2017 for examples). The focus of such research should also aim to identify which of these recommendations have garnered consistent evidence to their utility and effectiveness and identify the relative importance of recommendations based upon the development span. For instance, perhaps exaggerated non-verbal cues are instrumental with younger children, but off-putting to teenagers. This work would help clinicians best tailor their strategies to the developmental needs of the youth with whom they are working.

The TMH field is young and its future remains unclear. The field does not yet understand the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the trajectory of TMH support from funding agencies, government entities, insurance companies, and health and mental healthcare organizations. Despite this, the need for high quality TMH services—and digestible, evidence-informed resources such as this clinician guide—are clearly critical for supporting the future of child mental health practice.

Supplementary Material

References

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry on Telepsychiatry (2017). Clinical update: telepsychiatry with children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 875–893. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardito RB, & Rabellino D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 270. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett K, Davis B, Feil E, Sheeber L, Landry S, Leve C, & Johnson U. (2017). A randomized controlled trial examination of a remote parenting intervention: engagement and effects on parenting behavior and child abuse potential. Child Maltreatment, 22(4), 315–323. 10.1177/1077559517712000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, De Andrade ARV, Athay MM, Chen JI, De Nadai AS, Jordan-Arthur BL, & Karver MS (2012). The relationship between change in therapeutic alliance ratings and improvement in youth symptom severity: whose ratings matter the most? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(1–2), 78–89. 10.1007/s10488-011-0398-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batastini AB, King CM, Morgan RD, & McDaniel B. (2016). Telepsychological services with criminal justice and substance abuse clients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Services, 13(1), 20. 10.1037/ser0000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Boustani M, Gellatly R, & Chorpita BF (2018). Forty years of engagement research in children’s mental health services: Multidimensional measurement and practice elements. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 1–23. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1326121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Lee BR, Daleiden EL, Lindsey M, Brandt NE, & Chorpita BF (2015). The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 30–43. 10.1080/15374416.2013.814543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk MS, & Clarke S. (2019). Safety planning and risk management. In Berk RF(Ed.) Evidence-based treatment approaches for suicidal adolescents: Translating science into practice (pp. 63–84). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Boydell KM, Volpe T, & Pignatiello A. (2010). A qualitative study of young people’s perspectives on receiving psychiatric services via televideo. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(1), 5–11. 10.1007/s12553-017-0189-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, & Koppels T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104699. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman JE, Saunders R, Leibowitz J, & Minton R. (2021). The barriers, benefits and training needs of clinicians delivering psychological therapy via video. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campbell AF, & Simmonds JG (2011). Therapist perspectives on the therapeutic alliance with children and adolescents. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 24(3), 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Theodoros D, Russell T, Gillespie N, & Hartley N. (2019). Client, provider and community referrer perceptions of telehealth for the delivery of rural paediatric allied health services. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 27(5), 419–426. 10.1111/ajr.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle LL (2013). Child and adolescent telemental health. In Myers K. & Turvey CL (Eds.), Telemental health: Clinical, technical and administrative foundations for evidence-based practice (pp. 197–222). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter AL, Pincus DB, Furr JM, & Comer JS (2018). Working from home: An initial pilot examination of videoconferencing-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth delivered to the home setting. Behavior Therapy, 49(6), 917–930. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cejas I, Coto J, Sanchez C, Holcomb M, & Lorenzo NE (2021). Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Adolescents With Hearing Loss. Otology & Neurotology, 42(4), e470–e475. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000003006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, & Weisz JR (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5–20. 10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christon LM, McLeod BD, & Jensen-Doss A. (2015). Evidence-based assessment meets evidence-based treatment: An approach to science-informed case conceptualization. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 36–48. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CS (2018). Telepsychiatry in Asperger’s syndrome. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 35(4), 325–328. 10.1017/ipm.2017.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors EH, Douglas S, Jensen-Doss A, Landes SJ, Lewis CC, McLeod BD, … & Lyon AR (2020). What gets measured gets done: How mental health agencies can leverage measurement-based care for better patient care, clinician supports, and organizational goals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–16. 10.1007/s10488-020-01063-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee. (2012). Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1416–e1423. 10.1542/peds.2012-2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Leung VW, Pascoe R, Pang N, Iacono G, Austin A, & Dillon F. (2021). AFFIRM Online: Utilising an Affirmative Cognitive–Behavioural Digital Intervention to Improve Mental Health, Access, and Engagement among LGBTQA+ Youth and Young Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1541. 10.1177/1077559517712000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Crits-Christoph K, Narducci J, Schamberger M, & Gallop R. (2006). Can therapists be trained to improve their alliances? A preliminary study of alliance-fostering psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 16(3), 268–281. 10.1080/10503300500268557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crum KI, & Comer JS (2016). Using synchronous videoconferencing to deliver family-based mental healthcare. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(3), 229–234. 10.1089/cap.2015.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrat I, Tam S, Boulis M, & Williams AM (2021). Socioeconomic disparities in patient use of telehealth during the coronavirus disease 2019 surge. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 147(3), 287–295. 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.5161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca JS, Andorko ND, Chibani D, Jay SY, Rakhshan Rouhakhtar PJ, Petti E, … & Akouri-Shan L. (2020). Telepsychotherapy with youth at clinical high risk for psychosis: Clinical issues and best practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 304–331. 10.1037/int0000211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvins R, & Green J. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: An empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1167–1187. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather GC, Lincoln MA, & Ramsden R. (2017). Speech-language pathology telehealth in rural and remote schools: the experience of school executive and therapy assistants. Rural and Remote Health, 17(3), 1–13. 10.22605/RRH4225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella CA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Phillips GS, Bridge JA, Lester N, Sweeney HA, & Campo JV (2015). Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996–2010. JAMA Pediatrics. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PH, & Whitworth JM (2005). The role of nurses in telemedicine and child abuse. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 23(3), 127–131. 10.1097/00024665-200505000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KA, Duke DC, & Harris MA (2013). Behavioral health care for adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes via Skype: does working alliance remain intact? Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 7(3), 727–735. 10.1177/193229681300700318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hawley KM, Brookman-Frazee L, & Hurlburt MS (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain V, Marchand A, Bouchard S, Guay S, & Drouin MS (2010). Assessment of the therapeutic alliance in face-to-face or videoconference treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(1), 29–35. 10.1089/cyber.2009.0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloff NE, LeNoue SR, Novins DK, & Myers K. (2015). Telemental health for children and adolescents. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(6), 513–524. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1086322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glueck D. (2013). Establishing therapeutic rapport in telemental health. In Myers K. & Turvey CL(Eds.), Telemental health: Clinical, technical and administrative foundations for evidence-based practice (pp. 29–46). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Wen H, & Miller BF (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein F, & Glueck D. (2016). Developing rapport and therapeutic alliance during telemental health sessions with children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(3), 204–211. 10.1089/cap.2015.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosch EA, Flannery-Schroeder E, Mauro CF, & Compton SN (2006). Principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in children. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(3), 247–262. 10.1891/jcop.20.3.247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, & Brors B. (2014). circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics, 30(19), 2811–2812. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretier E, Minassian S, Benoit L, & Moro MR (2020). Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113264. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, & Garland AF (2008). Working alliance in adolescent outpatient therapy: Youth, parent and therapist reports and associations with therapy outcomes. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(2), 59–74. 10.1007/s10566-008-9050-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hines M, Bulkeley K, Dudley S, Cameron S, & Lincoln M. (2019). Delivering quality allied health services to children with complex disability via telepractice: Lessons learned from four case studies. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31(5), 593–609. 10.1007/s10882-019-09662-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hines M, Lincoln M, Ramsden R, Martinovich J, & Fairweather C. (2015). Speech pathologists’ perspectives on transitioning to telepractice: What factors promote acceptance? Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 21(8), 469–473. 10.1177/1357633X15604555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Freitag M, Walther M, Franklin SA, Ely L, & Woods DW (2012). A randomized pilot trial comparing videoconference versus face-to-face delivery of behavior therapy for childhood tic disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(9), 565–570. 10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, … & Bullmore E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ Jr, & Polo AJ (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301. 10.1080/15374410701820174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Novins DK, & Santiago CD (2010). The practice of evidence-based treatments in ethnic minority youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19(4), 775–789. 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Hoagwood K, Weisz JR, Hood K, Kratochwill TR, Vargas LA, & Banez GA (2010). A meta-systems approach to evidence-based practice for children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 65(2), 85–97. 10.1037/a0017784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton DD, June JD, & Kinn JT (2011). Technology-based suicide prevention: current applications and future directions. Telemedicine and e-Health, 17(1), 50–54. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman JB, Fields S, & Bickman L. (2006). Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 50–65. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus NM, Mobilio A, & King CA (2009). Parent–adolescent agreement concerning adolescents’ suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(2), 245–255. 10.1080/15374410802698412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JL, Martinez RG, Seager van Dyk IS, Emerson ND, Bursch BB (2020). COVID-19 Tips: Building rapport with adults via telehealth. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340414789_COVID-19_Tips_Building_Rapport_with_Adults_via_Telehealth

- Lame M, Leyden D, & Platt SL (2021). Geocode maps spotlight disparities in telehealth utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(3), 251–253. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langarizadeh M, Tabatabaei MS, Tavakol K, Naghipour M, Rostami A, & Moghbeli F. (2017). Telemental health care, an effective alternative to conventional mental care: A systematic review. Acta Informatica Medica, 25(4), 240–246. 10.5455/aim.2017.25.240-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Brandt NE, Becker KD, Lee BR, Barth RP, Daleiden EL, & Chorpita BF (2014). Identifying the common elements of treatment engagement interventions in children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(3), 283–298. 10.1007/s10567-013-0163-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, & Schwenk S. (2021). Technology-based mental health treatment and the impact on the therapeutic alliance update and commentary: How COVID-19 changed how we think about telemental health. Current Research in Psychiatry, 1(3), 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- McGill BC, Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, Ellis SJ, Robertson EG, & Cohn RJ (2017). Therapeutic alliance and group cohesion in an online support program for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: lessons from “Recapture Life”. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6(4), 568–572. 10.1089/jayao.2017.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD (2011). Relation of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(4), 603–616. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Sutherland KS, Martinez RG, Conroy MA, Snyder PA, & Southam-Gerow MA (2017). Identifying common practice elements to improve social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes of young children in early childhood classrooms. Prevention Science, 18(2), 204–213. 10.1007/s11121-016-0703-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon DU, & Belcher HM (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic Health Disparities and Pediatric Health Care—The Promise of Telehealth. JAMA Pediatrics. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkind MC, Shore JH, Bishop K, D’Amato K, Brame A, Thomas M, & Schneck CD (2020). Rapid conversion to telemental health services in response to COVID-19: experiences of two outpatient mental health clinics. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(7), 778–784. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkind MC, Shore JH, & Schneck CD (2021). Telemental Health Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Virtualization of Outpatient Care Now as a Pathway to the Future. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(7), 709–711. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R, & Hutton P. (2018). Practitioner Review: Therapist variability, patient-reported therapeutic alliance, and clinical outcomes in adolescents undergoing mental health treatment–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(1), 5–19. 10.1111/jcpp.12767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K. (2013). Telepsychiatry: time to connect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(3), 217–219. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, Nelson EL, Rabinowitz T, Hilty D, Baker D, Barnwell SS, … & Bernard J. (2017) American Telemedicine Association practice guidelines for telemental health with children and adolescents. Telemedicine and e-Health, 23(10), 779–804. 10.1089/tmj.2017.0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, & Comer JS (2016). The case for telemental health for improving the accessibility and quality of children’s mental health services. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(3), 186–191. 10.1089/cap.2015.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, March JS, & Franklin ME (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In Kendall PC (Ed.) Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures (pp. 297–321). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pramana G, Parmanto B, Lomas J, Lindhiem O, Kendall PC, & Silk J. (2018). Using mobile health gamification to facilitate cognitive behavioral therapy skills practice in child anxiety treatment: open clinical trial. JMIR Serious Games, 6(2), e9. 10.2196/games.8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H, Wade M, & Browne DT (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. 10.1037/amp0000660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Ramtekkar U, Bridge JA, Thomas G, Butter E, Reese J, Logan E, … & Axelson D. (2020). Pediatric telebehavioral health: a transformational shift in care delivery in the era of COVID-19. JMIR Mental Health, 7(9), e20157. 10.2196/20157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts EJ, Goetz AR, Capriotti MR, Bauer CC, Brei NG, Himle MB, … & Woods DW (2016). A randomized waitlist-controlled pilot trial of voice over Internet protocol-delivered behavior therapy for youth with chronic tic disorders. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 22(3), 153–162. 10.1177/1357633X15593192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP (2015). Youth suicide and access to guns. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(5), 429–430. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani PW, Kennedy SM, Sheffield K, Ament AM, Schiel MA, Hawks J, & Murphy J. (2021). Pediatric Mental Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions of the Delivery of Partial Hospitalization and Outpatient Services via Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 1–14. 10.1080/23794925.2021.1931985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DE, Ramtekkar U, & Zeković-Roth S. (2019). Telepsychiatry: a new treatment venue for pediatric depression. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 28(3), 377–395. 10.1016/j.chc.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA: URL http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Shirk S, & Jungbluth N. (2008). First-session pathways to the working alliance in cognitive–behavioral therapy for adolescent depression. Psychotherapy Research, 18(1), 15–27. 10.1080/10503300701697513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson WC, Arunagiri V, Funk AP, Ginsburg KL, Krychiw JK, Limowski AR, … & Stout Z. (2020). The nature and treatment of pandemic-related psychological distress. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50, 251–263. 10.1007/s10879-020-09463-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, & Lewis CC (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seager van Dyk IS, Kroll JL, Martinez RG, Emerson ND, Bursch BB (2020). COVID-19 Tips: Building rapport with youth via telehealth. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340066049_COVID-19_Tips_Building_Rapport_with_Youth_via_Telehealth

- Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Murray AL, Nivette A, Hepp U, … & Eisner M. (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. 10.1017/S003329172000241X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff A, Breiner CE, Ueno LF, Underwood SB, Merritt EC, Welch LM, … & Pieterse AL (2020). Shifting a training clinic to teletherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: a trainee perspective. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–11. 10.1080/09515070.2020.1786668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Sasser T, Schoenfelder Gonzalez E, Vander Stoep A, & Myers K. (2020). Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 30(7), 404–413. 10.1089/cap.2020.0062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver Z, Coger M, Barr S, & Drill R. (2020). Psychotherapy at a public hospital in the time of COVID-19: Telehealth and implications for practice. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–9. 10.1080/09515070.2020.1777390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SG, & Reid CL (2014). Therapeutic alliance in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A review. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22(6), 280–299. 10.1111/ajr.12149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotero L, Cunha D, da Silva JT, Escudero V, & Relvas AP (2017). Building alliances with (in)voluntary clients: A study focused on therapists’ observable behaviors. Family Process, 56(4), 819–834. 10.1111/famp.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HL, & Nobel J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254–263. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucala M, Schnur JB, Constantino MJ, Miller SJ, Brackman EH, & Montgomery GH (2012). The therapeutic relationship in e-therapy for mental health: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(4), e110. 10.2196/jmir.2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, Jiao D, Song R, Ma L, … & Liu, S. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592–598. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela J, Crosby LE, & Harrison RR (2020). Commentary: reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic and health disparities in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 839–841. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Raj SP, Moscato EL, & Narad ME (2019). Clinician perspectives delivering telehealth interventions to children/families impacted by pediatric traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(3), 298–306. 10.1037/rep0000268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Gies LM, Fisher AP, Moscato EL, Adlam AR, Bardoni A, … & Williams T. (2020). Telepsychotherapy with children and families: Lessons gleaned from two decades of translational research. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 332. 10.1037/int0000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, & Trikalinos TA (2012). Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr. Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium, 819–824. 10.1145/2110363.2110464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg H. (2020). Online group psychotherapy: Challenges and possibilities during COVID-19—A practice review. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 24(3), 201–211. 10.1037/gdn0000140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold BK (2020). Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom fatigue”. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(7), 437–438. 10.1089/cyber.2020.29188.bkw [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.