Abstract

A young woman in her 20s presented with fever, abdominal pain and malodourous vaginal discharge. She was found to be in septic shock, in the setting of a recent medical abortion with subsequent intrauterine device placement. Her blood cultures grew Fusobacterium necrophorum. Despite appropriate antibiotic therapy, the fever failed to defervesce. Subsequent evaluation revealed septic thrombophlebitis of the right gonadal vein and branches of the right iliac vein. She improved with a prolonged course of targeted antimicrobial therapy.

Keywords: Infectious diseases, Obstetrics and gynaecology

Background

Fusobacterium necrophorum is a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium that is frequently associated with oropharyngeal infections and septic thrombophlebitis of the neck veins.1 While this classic presentation is referred to as Lemierre’s syndrome, the organism has also been known to cause infections in other sites, especially the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.2 Myometritis can be frequently complicated by thrombophlebitis. To our knowledge, we describe the first case of F. necrophorum myometritis following a medical abortion and intrauterine device (IUD) insertion, which was complicated by septic thrombophlebitis of the pelvic veins.

Case presentation

A woman in her 20s presented to the emergency department with a 3-day history of fever, chills, malodourous vaginal discharge and lower abdominal pain. Her medical history was notable for a medical abortion she underwent 6 weeks prior to admission, and a Mirena IUD device placement 3 weeks prior to admission. On initial evaluation, she was febrile to 101.0°F (38.3°C), tachypnoeic to 22 breaths per minute and tachycardic to 130 beats per minute, with hypotension (blood pressure 76/50 mm Hg) that was not responsive to fluid resuscitation. Physical examination revealed a young Asian woman, not in acute distress. Abdominal examination demonstrated lower abdominal tenderness, with no guarding. Pelvic examination was positive for purulent vaginal discharge, visualisation of the IUD strings, and uterine and right adnexal tenderness. The cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological and cutaneous examination was normal.

A diagnosis of septic shock secondary to myometritis was made. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for vasopressor support and further management. She was initiated on broad-spectrum antibiotics with intravenous vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam and clindamycin given potential toxic shock syndrome.

Investigations

On investigation, she was noted to have a normocytic anaemia, with neutrophilic leucocytosis (Hemoglobin 10.1 g/L, white cell count 11.2×109 cells/L, 89.5% neutrophils and platelets 180×109/L). She had a normal blood chemistry, normal renal function (creatinine 0.8 mg/dL) with lactic acidosis (4.9 mmol/L), which improved with fluid resuscitation and resolution of septic shock.

She underwent a transvaginal ultrasound which showed a malpositioned IUD with arms embedded in the myometrium and imaging findings consistent with myometritis. Her anaerobic blood cultures grew F. necrophorum. Screening for other sexually transmitted infections was negative.

Differential diagnosis

Initial differentials considered included myometritis secondary to retained products of conception, uterine abscess/collection and uterine rupture due to the recent procedures.

Treatment

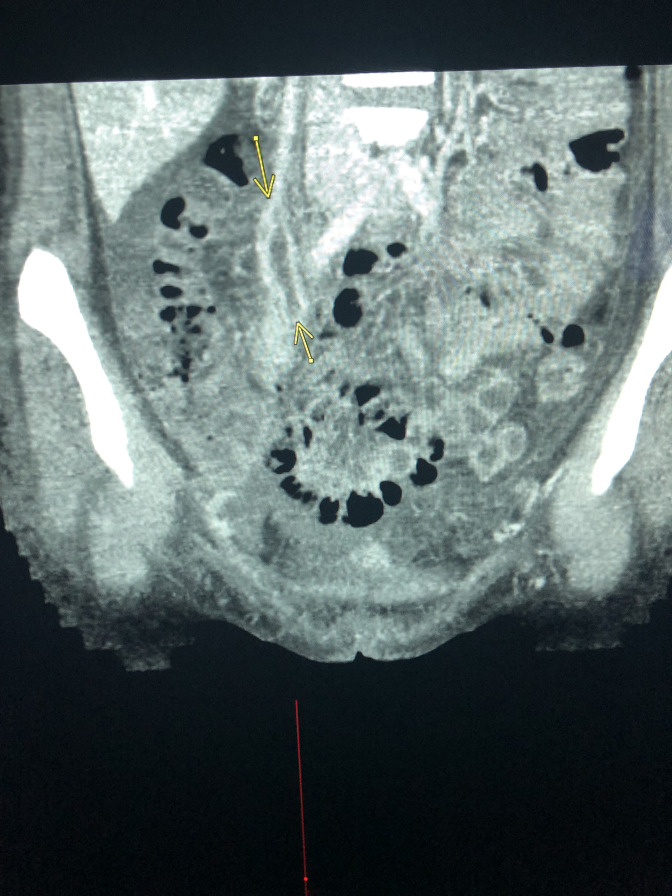

She underwent interval removal of the IUD, and her shock resolved. After blood culture identification of F. necrophorum, antibiotics were narrowed to monotherapy with metronidazole. Despite being on appropriate antimicrobial therapy, she persisted to have high spiking fevers. Given the known thrombogenic nature of Fusobacterium spp, she underwent cross sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis. CT angiogram revealed a thrombus in the right gonadal vein and branches of the right iliac vein (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sagittal view of a CT angiogram of the pelvis showing thrombi in the right gonadal vein and branches of the iliac vein (arrows).

Outcome and follow-up

Hence, a diagnosis of F. necrophorum pelvic septic thrombophlebitis secondary to a malpositioned IUD after a medical abortion was made. Antimicrobial therapy was continued, and fever resolved by day 5 of hospitalisation. She completed a 6-week course of antibiotics, and at follow-up, was doing well.

Discussion

This case report highlights an unusual presentation of septic pelvic thrombophlebitis secondary to F. necrophorum myometritis.

To our knowledge, this is the first case describing septic thrombophlebitis of the pelvis associated with a medical abortion and now one of several associated with an IUD. A recent study showed that the incidence of Fusarium species bacteraemia was estimated between 0.19% and 0.9% of all bacteraemias.3 Fusobacterium spp can colonise the genitourinary tract; however, septic thrombophlebitis of the pelvis is a rare finding and infection is much more commonly associated with internal jugular vein thrombosis for unclear reasons, although several mechanisms have been proposed. This includes haematogenous spread via the tonsillar vein resulting in thrombosis, or through invasion of the peritonsillar tissue and subsequent spread to the lateral pharyngeal space from the lymphatic system resulting in perivenous inflammation and luminal thrombosis. Alternative hypotheses include development of thrombophlebitis through translocation from tonsillar abscesses as well as alteration of the pharyngeal mucosa by bacterial organisms allowing for local invasion of F. necrophorum to the internal jugular vein.4 We suspect either the medical abortion or the subsequent IUD placement led to local F. necrophorum translocation, resulting in our patient’s pelvic findings. One prior case has described Lemierre’s syndrome occurring after a medical abortion; however, septic thrombophlebitis was isolated to the internal jugular vein and cervical cultures were positive for F. necrophorum, suggesting haematogenous dissemination.5 A separate case noted septic thrombophlebitis of the ovarian vein in a patient with an IUD present for years without recent placement or manipulation, unlike our case.6 One more recent report diagnosed septic thrombophlebitis 3 days after an IUD insertion.7 Similar to our case, clinical improvement occurred after IUD removal, and this should be considered in the management of future cases.

Fusobacteria are anaerobic gram-negative bacteria that constitute the normal flora of the oropharynx and upper respiratory tracts. In 1936, Andre Lemierre described the first cases of postanginal anaerobic septicaemias with thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular veins, going on to cause septic emboli.1 Lemierre’s syndrome, as this condition has come to be known, is generally seen in young, previously healthy adults. There has been a resurgence in recent years, which has been attributed to a decrease in antibiotic prescriptions for sore throats.8

While septic emboli to the pulmonary vessels are most common, embolisation to osteoarticular, soft tissues, genitourinary, central nervous system and endovascular sites are also well described. Primary infection of the genitourinary and gastrointestinal sites are rarer than the classical Lemierre’s syndrome and is more frequently described in older individuals with underlying comorbid conditions such as a malignancy.2 While preterm labour and chorioamnionitis can be associated with anaerobic sepsis, our case is unique in the site of infection and the occurrence in a young, previously healthy adult.9

Fusobacteria are intrinsically resistant to fluoroquinolones, macrolides, aminoglycosides and tetracyclines, and the choice of antibiotics include metronidazole and clindamycin; however, beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors harbouring activity against anaerobes such as ampicillin-sulbactam or piperacillin-tazobactam are commonly used. Antibiotics are usually prescribed for 4–6 weeks.10

Anticoagulation remains controversial, with most patients having good outcomes in spite of not receiving anticoagulation, as evidenced in a recent observational study of 82 patients.11 While the use of anticoagulation in septic pelvic thrombophlebitis has been previously cited to be beneficial, a recent randomised trial of patients with puerperal septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, failed to demonstrate differences in time to fever defervescence, duration of hospitalisation or long-term sequelae.12 Our patient did not receive anticoagulation and her fever defervesced by day 5 with a good long-term outcome on antibiotic therapy alone.

In conclusion, F. necrophorum can rarely be associated with septic myometritis and pelvic thrombophlebitis. The case also highlights the thrombogenic nature of this anaerobic bacterial infection.

Learning points.

Fusobacterium necrophorum can rarely be associated with septic myometritis and pelvic thrombophlebitis.

The case also highlights the thrombogenic nature of this anaerobic bacterial infection.

Footnotes

Contributors: KMK drafted the manuscript. WM and SCR reviewed and edited the manuscript prior to submission. KMK, WM and SCR were involved in the care of the patient. SCR gave the final approval.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Riordan T. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:622–59. 10.1128/CMR.00011-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valerio L, Zane F, Sacco C, et al. Patients with Lemierre syndrome have a high risk of new thromboembolic complications, clinical sequelae and death: an analysis of 712 cases. J Intern Med 2021;289:325–39. 10.1111/joim.13114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg EA, Venkat-Ramani T, Hewit M, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of patients with Fusobacterium bacteraemia. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:325–9. 10.1017/S0950268812000660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuppali K, Livorsi D, Talati NJ. Lemierre’s syndrome due to Fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:805–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedengran KK, Hertz J. Lemierre's syndrome after evacuation of the uterus: a case report. Clin Case Rep 2014;2:60–1. 10.1002/ccr3.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huynh-Moynot S, Commandeur D, Danguy des Déserts M, et al. [Septic shock Fusobacterium necrophorum from origin gynecological at complicated an acute respiratory distress syndrome: a variant of Lemierre's syndrome]. Ann Biol Clin 2011;69:202–7. 10.1684/abc.2011.0538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto S, Okamoto K, Okugawa S, et al. Fusobacterium necrophorum septic pelvic thrombophlebitis after intrauterine device insertion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;145:122–3. 10.1002/ijgo.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurencet M-E, Rosset-Zufferey S, Schrenzel J. Atypical presentation of Lemierre's syndrome: case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:868. 10.1186/s12879-019-4538-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czikk MJ, McCarthy FP, Murphy KE. Chorioamnionitis: from pathogenesis to treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:1304–11. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre's syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2000;2:168–73. 10.1007/s11908-000-0030-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nygren D, Elf J, Torisson G, et al. Jugular Vein Thrombosis and Anticoagulation Therapy in Lemierre's Syndrome-A Post Hoc Observational and Population-Based Study of 82 Patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8:ofaa585. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown CE, Stettler RW, Twickler D, et al. Puerperal septic pelvic thrombophlebitis: incidence and response to heparin therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:143–8. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70450-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]