Summary

Up to 45% of esophageal atresia (EA) patients undergo fundoplication during childhood. Their esophageal dysmotility may predispose to worse fundoplication outcomes compared with patients without EA. We therefore compared fundoplication outcomes and symptoms pre- and post-fundoplication in EA patients with matched patients without EA. A retrospective review of patients with- and without EA who underwent a fundoplication was performed between 2006 and 2017. Therapeutic success was defined as complete sustained resolution of symptoms that were the reason to perform fundoplication. Fundoplication indications of 39 EA patients (49% male; median age 1.1 [0.1–17.0] yrs) and 39 non-EA patients (46% male; median age 1.3 [0.3–17.0] yrs) included respiratory symptoms, brief resolved unexplained events, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, recurrent strictures and respiratory problems. Post-fundoplication, therapeutic success was achieved in 5 (13%) EA patients versus 29 (74%) non-EA patients (P<0.001). Despite therapeutic success, all 5 (13%) EA patients developed postoperative sustained symptoms/complications versus 12 (31%) non-EA patients. Eleven (28%) EA patients versus 3 (8%) non-EA patients did not achieve any therapeutic success (P=0.036). Remaining patients achieved partial therapeutic success. EA patients suffered significantly more often from postoperative sustained dysphagia (41% vs. 13%; P=0.039), gagging (33% vs. 23%; P<0.001) and bloating (40% vs. 17%; P=0.022). Fundoplication outcomes in EA patients are poor and EA patients are more susceptible to post-fundoplication sustained symptoms and complications compared with patients without EA. The decision to perform fundoplication in EA patients with proven gastroesophageal reflux disease needs to be made with caution after thorough multidisciplinary evaluation.

Keywords: esophageal atresia, fundoplication, gastroesophageal reflux disease

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal atresia is a congenital anomaly which occurs in  2.4:10 000 births.1,2 As a result of esophageal dysmotility, dysphagia is common and up to 70% of these patients suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after surgical repair.3

2.4:10 000 births.1,2 As a result of esophageal dysmotility, dysphagia is common and up to 70% of these patients suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after surgical repair.3

Fundoplications are performed in up to 45% of EA patients and almost all long-gap EA patients.4–8 A fundoplication aims to reduce gastroesophageal reflux (GER) by increasing the resistance to retrograde flow at the level of the esophagogastric junction, but it thereby also hampers antegrade flow from the esophagus to the stomach.9–11 Complications include worsening of preexistent dysphagia, new-onset dysphagia, bloating, gagging/retching and feeding difficulties.7,12 Fundoplication can also increase esophageal stasis, resulting in an increased direct aspiration risk, worsening of respiratory symptoms and/or brief resolved unexplained events (BRUEs).13 In addition, dumping syndrome can occur in patients post-fundoplication.14,15 Wrap failure and recurrent GERD symptoms are reported in up to 45% of EA patients16–20 versus 4–10% in patients without EA.18

We hypothesized that fundoplication outcomes in EA patients would be worse compared with patients without EA, because of their preexistent esophageal dysmotility and abnormal esophageal anatomy. We additionally hypothesized that differences in outcomes could also be due to poor patient selection in the EA cohort due to a lack of multidisciplinary evaluation pre-fundoplication. Esophageal symptoms in EA patients are often difficult to interpret. EA patients can incorrectly be diagnosed with therapy-resistant GERD, when their symptoms may be due to esophageal dysmotility, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) or esophageal strictures.5 Performing a fundoplication in these patients therefore often does not result in symptom improvement.

In this study, we aimed to assess fundoplication indications, preoperative workup, pre- and post-fundoplication symptoms, as well as post-fundoplication complications in EA patients and compare those with results from patients without EA.

METHODS

Study subjects

EA patients (0–18 years) who underwent a fundoplication between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2017 in Sydney (Australia), Nagpur (India) or Amsterdam (The Netherlands), were included. Patients with EA type E (i.e. H-fistula without esophageal atresia) and patients who underwent esophageal replacement therapy before fundoplication were excluded.

For each EA patient, a patient without EA, with same age and gender at time of fundoplication was selected. If multiple patients were available, the patient with the closest corresponding age was selected. If a gender match was not available, only age-matching occurred.

Ethical approval in Australia and India was obtained from the local institutional review boards. Because of the observational nature of this study, AMC ethical committee judged that formal approval of a medical ethical review board was not required in The Netherlands (reference number: W20_403#20.451). According to local legislation, Dutch patients were sent an information flyer in which they were asked for permission to use their medical data for this study. Patients were given 6 weeks to opt out.

Study design

Retrospective chart review in EA patients and patients without EA who underwent a fundoplication.

Study parameters

Patient characteristics, data regarding fundoplication indication, fundoplication techniques and outcomes were collected, as well as data regarding pre- and post-fundoplication investigations (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD], pH [−impedance, pH-MII] testing and/or contrast esophagogram).

Reasons that led to the decision to perform a fundoplication were subdivided into: (i) proven GERD or typical GERD symptoms (i.e. back arching and/or gulping related to feeds in younger children, heartburn and/or chest pain in older children and/or regurgitation, erosive esophagitis or intestinal metaplasia on EGD and/or abnormal pH-MII results); (ii) recurrent strictures; (iii) respiratory symptoms; (iv) intestinal metaplasia; (v) BRUE.

Post-fundoplication complications and symptoms were categorized into:

Postoperative perforation (leakage from the distal esophagus or stomach, seen on contrast study/CT scan) and/or infection (raised inflammatory markers and requirement of antibiotic therapy);

New-onset sustained (>8 weeks) symptoms: dysphagia; bloating; gagging/retching; dumping symptoms and/or feeding difficulties;

Recurrent and sustained symptoms (> 8 weeks)

Therapeutic success was defined as ‘complete and sustained (>8 weeks) resolution of symptoms that were the primary reason to perform a fundoplication’.

Post-fundoplication, patients were categorized into one of the following therapeutic outcome groups:

Therapeutic success without development of sustained post-fundoplication symptoms/complications

Therapeutic success with development of new-onset or recurrent sustained post-fundoplication symptoms/complications

Partial therapeutic success (i.e. resolution of only a part of symptoms that were the primary reason to perform the fundoplication)

No therapeutic success at all

Statistical analysis

SPSS (IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS] Statistics for Windows, v 26.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for descriptive analyses. Data were noted as median and range or as frequency (%). Patient characteristics, preoperative symptoms, fundoplication indications and results of post-fundoplication symptoms in EA patients were compared with those of non-EA patients, using χ2 test in case of ≥10 cases and Fisher’s Exact test in case of <10 patients. Pre- versus post-fundoplication symptoms/complications were calculated using paired t-test. Comparisons of the four abovementioned treatment outcomes between EA patients and non-EA patients were calculated using χ2 test for trend. We considered a P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2017, 39 EA patients (49% male, median age 1.2 (0.1–17.0) yrs, Table 1) and 39 matched patients without EA (46% male, median age 1.3 [0.3–17.0] yrs) underwent a fundoplication. Age- and sex-matching was possible in 38/39 patients, in one case only age-matching was performed.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of patients born with EA and patients without EA

| Characteristics | EA patients | Non-EA patients | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, [%]) | Male | 19 (49) | 18 (46) | ns |

| Median age (range) | 1.2 (0.1–17.0) yrs | 1.3 (0.3–17.0) yrs | ns | |

| Median follow-up (range) | 8.0 (0.5–12.0) yrs | 7.5 (0.6–12) yrs | ns | |

| EA type (n, [%]) | Type A | 4 (10) | n/a | n/a |

| Type C | 35 (90) | n/a | n/a | |

| Type of surgical EA repair (n, [%]) | Primary | 34 (87) | n/a | n/a |

| Delayed | 5 (13) | n/a | n/a | |

| Fundoplication indication (n, [%]) | Recurrent strictures typical GERD symptoms intestinal metaplasia respiratory symptoms BRUE | 31 (79) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| 31 (79) | 39 (100) | 0.006 | ||

| 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ns | ||

| 20 (51) | 23 (59) | ns | ||

| 9 (23) | 7 (18) | na | ||

| Type of fundoplication (n, [%]) | Complete | 32 (83) | 35 (90) | ns |

| Partial | 7 (18) | 4 (10) | ns | |

| Open | 7 (18) | 6 (15) | ns | |

| Laparoscopic | 32 (83) | 33 (85) | ns | |

| Medication at time of fundoplication (n, [%]) | PPI | 38 (97) | 35 (90) | ns |

| Prokinetics | 27 (69) | 31 (79) | ns | |

| Tube feeds | 22 (56) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| H2RA | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | ns | |

| Baclofen | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ns |

EA, esophageal atresia; GI, gastrointestinal; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; H2RA, H2RA receptor antagonist.

Four EA patients (10%) suffered from congenital heart disease, 15 (38%) had associated VACTERL conditions and 1 (3%) patient was diagnosed with CHARGE syndrome. Two EA patients (5%) were prematurely born (<34 weeks).

Twenty-four (62%) patients without EA had a diagnosis of GERD, considered severe enough to perform a fundoplication, without comorbidities, whereas 15 (38%) suffered from GERD in combination with the following comorbidities: failure to thrive (n = 10, 26%), prematurely born (n = 6, 15%), anemia (n = 4, 10%), congenital diaphragmatic hernia (n = 1, 3%) or para-esophageal hernia (n = 1, 3%).

Median follow-up was 8.0 (0.5–12.0) years versus 7.5 (0.6–12.0) years for patients with- and without EA, respectively.

Preoperative symptoms and indication for fundoplication

EA patients were significantly more often on tube feeds at time of fundoplication (56% vs. 0%; P < 0.001, Table 1). Preoperative dysphagia (46% vs. 0%; P < 0.001) and feeding difficulties (28% vs. 0%; P < 0.001) were reported significantly more often in EA patients compared with non-EA patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pre and postoperative symptoms in EA patients versus controls

| Preoperative symptoms | EA patients (n = 40) | Non-EA patients (n = 40) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative symptoms | Dysphagia | 18 (46) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Gagging | 5 (13) | 1 (3) | ns | |

| Dumping | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ns | |

| Regurgitation | 25 (64) | 26 (67) | ns | |

| Feeding difficulties | 11 (28) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Bloating | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ns | |

| Failure to thrive | 22 (56) | 16 (41) | ns | |

| Postoperative symptoms, complications and post-fundoplication therapies | ||||

| Surgical complications | (leak/infection) | 7 (18) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 |

| All postoperative symptoms | Dysphagia | 32 (82) | 4 (10) | <0.001 |

| Gagging | 18 (46) | 9 (23) | ns | |

| Dumping | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | ns | |

| Regurgitation | 3 (8) | 11 (28) | ns | |

| Feeding difficulties | 15 (38) | 1 (3) | <0.001 | |

| Bloating | 16 (41) | 6 (15) | 0.022 | |

| Newly developed sustained symptoms postoperatively | ||||

| Dysphagia | 16 (41) | 4 (13) | 0.039 | |

| Gagging | 13 (33) | 9 (23) | <0.001 | |

| Dumping | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | ns | |

| Regurgitation | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | ns | |

| Feeding difficulties | 11 (28) | 1 (3) | ns | |

| Bloating | 16 (41) | 6 (15) | 0.022 | |

| Recurrent sustained symptoms | Any symptom recurrence | 36 (92) | 11 (28) | <0.001 |

| GERD | 30 (78) | 11 (28) | <0.001 | |

| Stricture | 13 (33) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 10 (25) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| Treatment for GERD post-fundoplication | PPI | 34 (88) | 11 (28) | <0.001 |

| Redo fundoplication | 4 (10) | 3 (8) | ns | |

| Esophageal replacement | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

EA, esophageal atresia; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease

Thirty-two EA patients (82%) and 24 (62%) non-EA patients had more than one indication for fundoplication. Respiratory symptoms that were believed to be a consequence of GERD and recurrent BRUEs were the reason for fundoplication in a similar number of EA versus non-EA patients (51% vs. 59% and 23% vs. 18%, respectively; Table 1). Recurrent strictures as an indication for fundoplication were only reported in EA patients (79% vs. 0%; P < 0.001). Typical GERD symptoms/complications were less frequently reported in EA patients compared with non-EA patients (82% vs. 100%; P = 0.006). One EA patient (6 year old, EA subtype A) had intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus at time of fundoplication.

Investigations performed before fundoplication

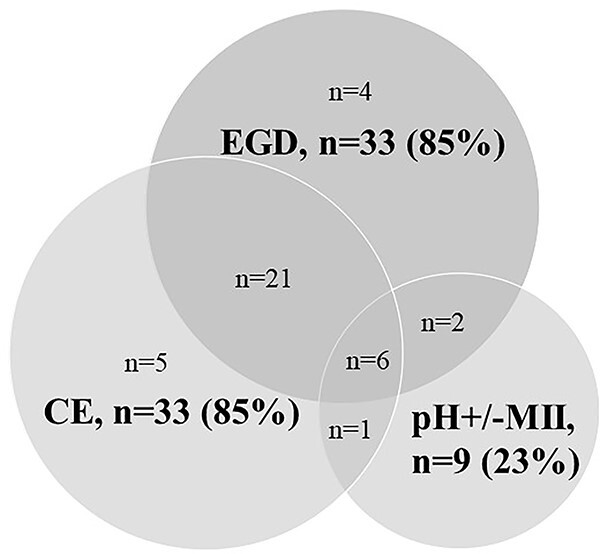

In EA patients, investigations performed before fundoplication included EGD in 33 (85%), contrast esophagogram in 33 (85%) and pH (+/−MII) measurement in 9 (23%). Six EA patients (15%) underwent all three tests (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic tests performed in EA patients before fundoplication EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; CE, contrast esophagogram; pH+/−MII = pH +/−Multichannel intraluminal impedance measurement.

In EA patients, preoperative EGD (n = 33) revealed abnormalities in 12/33 (36%) children, including esophageal strictures in 6 (18%), EoE in 4 (12%, >15 eosinophils/HPF and macroscopic furrowing and exudate), hiatal hernia in 2 (6%), intestinal metaplasia in 1 (3%) and reflux esophagitis in 1 (3%). Patients with EoE showed decrease in eosinophils (<5/HPF) on budesonide slurry; however, therapy refractory GERD with persistent symptoms, abnormal pH-MII, erosive esophagitis and intestinal metaplasia (n = 1) was still present which led to the decision to proceed with fundoplication. Contrast esophagograms (n = 34) showed strictures in 6 (18%), hiatal hernia in 2 (6%) and esophageal diverticulum in 1 (3%). Although 31 (79%) EA patients suffered from recurrent strictures (Table 1), not all of these patients had a stricture at time of preoperative screening as a result of recent dilation.

Of 9 pH-MII studies performed, 7/9 (78%) were abnormal (n = 5 positive symptom association; n = 2 positive symptom association and increased number of retrograde bolus movements; none showed elevated acid exposure times).

Twenty-six EA patients did not have any abnormality reported on any of the abovementioned preoperative tests. Despite this, the decision to proceed to fundoplication was made on clinical grounds. Of these patients, 16 underwent EGD and contrast esophagogram, 5 underwent contrast esophagogram only, 4 EGD only and 1 patient underwent pH-impedance and contrast esophagogram.

In patients without EA, 38/39 (97%) underwent preoperative testing: 38/39 underwent EGD, which revealed reflux esophagitis in 4/38 (11%) cases. Contrast esophagograms were performed in 36/39 (92%) non-EA patients, all showed normal results. None of them underwent pH-MII testing.

Fundoplication techniques

There was no significant difference in surgical techniques between both groups (Table 1). All EA patients who underwent a partial fundoplication (n = 7) had preoperative dysphagia and three of them also had EoE. EA patients who underwent a complete fundoplication suffered significantly more often from regurgitation preoperatively (P = 0.03).

Post-fundoplication complications

In one EA patient who underwent an open partial fundoplication, a gastric perforation and pleural effusion were detected 3 days post-fundoplication on CT scan. Patient underwent a relaparotomy for closure of the perforation and insertion of a chest drain. Postoperatively, he received intravenous antibiotics.

Post-fundoplication outcomes

EA patients had significantly worse fundoplication outcomes (Table 3). None of them achieved complete therapeutic success without development of symptoms/complications versus 17 (44%) non-EA patients (P < 0.001). In addition, 28% of EA patients had no therapeutic success at all versus 8% in patients without EA (P = 0.036).

Table 3.

Fundoplication outcome in EA patients

| Fundoplication outcome: | EA patients (%) | Non-EA patients (%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete therapeutic success, without development of postoperative sustained symptoms/complications | 0 (0%) | 17 (43%) | <0.001 |

| Complete therapeutic success, with development of postoperative sustained symptoms/complications | 5 (13%) | 11 (30%) | ns |

| Partial therapeutic success | 23 (60%) | 8 (20%) | 0.001 |

| No therapeutic success at all | 11 (28%) | 3 (8%) | 0.036 |

Therapeutic success = improvement of symptoms/diseases that were the reason to perform a fundoplication.

χ2 test for trend: EA patients have significantly different treatment outcomes compared with controls, P = <0.001. *Post hoc testing with χ2 test.

Regurgitation, respiratory symptoms and strictures reduced postoperatively in a significant number of EA patients (P < 0.001, P = 0.002 and P = 0.022 respectively, Table 4). In non-EA patients, typical GERD symptoms/complications and respiratory symptoms also significantly decreased (P < 0.001, Table 4).

Table 4.

Pre versus postoperative symptoms in EA patients and controls

| EA patients | Preoperative | Postoperative | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysphagia | 18 (46) | 32 (82) | <0.001 |

| Gagging | 5 (13) | 18 (46) | <0.001 |

| Dumping | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | ns |

| Regurgitation | 25 (65) | 4 (10) | <0.001 |

| Feeding difficulties | 11 (28) | 15 (38) | ns |

| Bloating | 0 (0) | 16 (40) | <0.001 |

| GERD | 31 (80) | 26 (65) | ns |

| Strictures | 30 (78) | 13 (33) | 0.008 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 22 (56) | 10 (25) | 0.002 |

| Non-EA patients | Preoperative | Postoperative | P value |

| Dysphagia | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 0.044 |

| Gagging | 1 (3) | 9 (23) | 0.010 |

| Dumping | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ns |

| Feeding difficulties | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ns |

| Bloating | 0 (0) | 6 (15) | 0.012 |

| GERD | 39 (100) | 10 (26) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 23 (59) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

EA, esophageal atresia; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Symptom recurrence occurred in significantly more EA patients (36/39 [92%]) compared with non-EA patients (11/39 [28%], P < 0.001; Table 2) after a median time of 60 (1–360) days (n = 2 missing data regarding time of symptom recurrence).

Significantly more EA patients suffered from newly developed sustained dysphagia (41% vs. 13%; P = 0.039) and bloating (40% vs. 18%; P = 0.022) compared with patients without EA (Table 2). No differences in post-fundoplication outcomes were found between EA patients who underwent a partial versus a complete fundoplication (see Supplementary File 1).

Thirty-four (87%) EA patients were back on acid suppressive therapy after a median of 60 (12–360) days versus 11 (28%) patients without EA (P = 0.05, Table 2). Of the EA patients, 4/39 (10%) underwent a redo-fundoplication within the first 3 months post-fundoplication versus 3/40 (8%) patients without EA. Esophageal replacement surgery was performed in 4/39 (10%) EA patients who suffered from recalcitrant strictures despite fundoplication (Table 2).

Discussion

In this multicenter retrospective study, we show that fundoplication outcomes in EA patients were poor, with only 13% of EA patients achieving complete therapeutic success (vs. 73% of non-EA patients). Despite this, post-fundoplication sustained symptoms/complications were present in all EA patients (vs. 41% of non-EA patients) with therapeutic success. In addition, partial- or complete symptom recurrence, and new-onset symptoms post-fundoplication were significantly more frequent in the EA cohort compared with patients without EA.

In our study, preoperative workup was often incomplete and atypical clinical presentations were considered an indication for fundoplication, despite the lack of evidence for a causal relation between GERD and symptoms. This suggests that patient selection may be an important contributing factor for these poor outcomes.

In line with our results, others have shown that a significant proportion of EA patients experience symptom recurrence post-fundoplication.16,17,21,22 A retrospective study showed similar redo-rates to our study, in patients with and without EA (13% vs. 8%).23 In that study, however, recurrent symptoms or complications post-surgery were not compared and assessed in both groups, and controls were not age-matched.23

Another pediatric study which retrospectively compared 86 EA patients with and without fundoplication, also showed poor outcome post-fundoplication in the EA cohort.8 In the same study, the vast majority remained symptomatic post-fundoplication and 13% (vs. 10% in our cohort) needed redo-fundoplication.8 Similar to our findings, patients with preoperative regurgitation or respiratory symptoms achieved only partial symptom relief post-fundoplication.8 Postoperative endoscopic results showed similar rates of reflux esophagitis and intestinal metaplasia to our study.8 Another retrospective pediatric study reported that a history of fundoplication had no effect on the likelihood of having subsequent abnormal pH-MII results or microscopic esophagitis.24

In our cohort, regurgitation and respiratory symptoms decreased significantly in the EA cohort, as well as the number of strictures post-fundoplication. A recently published study evaluating outcomes of pH-MII and EGD performed in EA patients aged 1 year showed a significant higher likelihood of having abnormal pH-MII results in patients with a history of recurrent strictures implying that GERD plays a role in stricture development.24 However, pharmacological anti-reflux therapy does not prevent the recurrence of esophageal strictures.25–27 and it was therefore hypothesized that GERD is not the sole cause of strictures.

Interestingly, in our cohort, a large proportion of patients did not have a complete multidisciplinary preoperative workup. It might well be, that some of our EA patients who had symptoms suggestive of GERD, were in fact symptomatic secondary to esophageal dysmotility, direct aspiration due to laryngeal cleft, recurrent fistula, EoE, tracheomalacia and/or feeding difficulties secondary to oral aversion. This stresses the need to perform a thorough preoperative multidisciplinary evaluation as per ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guidelines in all EA patients in whom fundoplication is being considered.5 This will help optimize patient selection and prevent patients without GERD from an unnecessary procedure with poor symptom relief and possibly new onset symptoms and/or complications. A prospective study in a cohort of EA patients that have been carefully selected for fundoplication according to the guideline recommendations, will be a first step to assess the true efficacy of fundoplication in EA patients with GERD refractory to medical anti reflux therapy.

In addition, ongoing research may provide better tools for a preoperative workup. In children without EA, small studies have shown that combined impedance-manometry testing with pressure flow analysis may be useful to predict outcome including dysphagia risk post-surgery.28,29 Trials incorporating such preoperative tools are clearly needed to better select those EA patients that will most benefit from fundoplication along with reduced risk of complications post-surgery.

A limitation of our study is its retrospective design, which may have led to underreporting of pre and postoperative symptoms and missing data regarding preoperative investigations.

Our study has several strengths too. This is the first study that examined preoperative diagnostic workup, pre- and post-fundoplication symptoms and post-fundoplication outcomes in pediatric EA patients and compared these outcomes with matched patients without EA. By collecting data from three international EA centers, we managed to build a large cohort of patients and overcome institutional selection bias.

Conclusion

Fundoplication outcomes in EA patients are poor. Symptom recurrence and new-onset symptoms post-fundoplication occurred significantly more often in EA patients compared with patients without EA. We showed that patient selection may be a factor contributing to these poor outcomes. Preoperative workup was often incomplete and fundoplications were performed despite the lack of evidence for a causal relation between GER and symptoms.

Fundoplications should only be considered in EA patients with proven GERD where no other options are available after thorough multidisciplinary evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Marinde van Lennep, Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Eric Chung, Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Ashish Jiwane, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Rajendra Saoji, Children’s Surgical and Endoscopy Center, Midas Heights, Nagpur, India.

Ramon R Gorter, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Marc A Benninga, Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Usha Krishnan, Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; Discipline of Paediatrics, School of Women’s and Children’s Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Michiel P van Wijk, Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- 1. Pedersen R N, Calzolari E, Husby S, Garne E, group EW . Oesophageal atresia: prevalence, prenatal diagnosis and associated anomalies in 23 European regions. Arch Dis Child 2012; 97(3): 227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nassar N, Leoncini E, Amar E et al. Prevalence of esophageal atresia among 18 international birth defects surveillance programs. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2012; 94(11): 893–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Lennep M, MMJ S, Dalloglio L et al. Oesophageal atresia. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5(1): 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vergouwe F W T, Ijsselstijn H, Biermann K et al. High prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after repair of esophageal atresia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16(4): 513–21.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krishnan U, Mousa H, Dall'Oglio L et al. ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of gastrointestinal and nutritional complications in children with esophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 63(5): 550–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alfaro L, Bermas H, Fenoglio M, Parker R, Janik J S. Are patients who have had a tracheoesophageal fistula repair during infancy at risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma during adulthood? J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40(4): 719–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rintala R J. Fundoplication in patients with esophageal atresia: patient selection, indications, and outcomes. Front Pediatr 2017; 5:109. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00109. eCollection 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koivusalo A I, Rintala R J, Pakarinen M P. Outcomes of fundoplication in oesophageal atresia associated gastrooesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53(2): 230–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kwiatek M A, Kahrilas P J, Soper N J et al. Esophagogastric junction distensibility after fundoplication assessed with a novel functional luminal imaging probe. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14(2): 268–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeMeester T R, Bonavina L, Albertucci M. Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Evaluation of primary repair in 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 1986; 204(1): 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Broeders J A, Rijnhart-de Jong H G, Draaisma W A, Bredenoord A J, Smout A J, Gooszen H G. Ten-year outcome of laparoscopic and conventional nissen fundoplication: randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2009; 250(5): 698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson K, Zendejas B, Kamran A et al. Predictors of anti-reflux procedure failure in complex esophageal atresia patients. J Pediatr Surg 2021; S0022–3468(21)00546–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.08.005. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slater B J, Rothenberg S S. Fundoplication. Clin Perinatol 2017; 44(4): 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bufler P, Ehringhaus C, Koletzko S. Dumping syndrome: a common problem following Nissen fundoplication in young children. Pediatr Surg Int 2001; 17(5): 351–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Samuk I, Afriat R, Horne T, Bistritzer T, Barr J, Vinograd I. Dumping syndrome following nissen fundoplication, diagnosis, and treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1996; 23(3): 235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindahl H, Rintala R, Louhimo I. Failure of the Nissen fundoplication to control gastroesophageal reflux in esophageal atresia patients. J Pediatr Surg 1989; 24(10): 985–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corbally M T, Muftah M, Guiney E J. Nissen fundoplication for gastro-esophageal reflux in repaired tracheo-esophageal fistula. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1992; 2(06): 332–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Snyder C L, Ramachandran V, Kennedy A P, Gittes G K, Ashcraft K W, Holder T M. Efficacy of partial wrap fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux after repair of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32(7): 1089–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wheatley M J, Coran A G, Wesley J R. Efficacy of the Nissen fundoplication in the management of gastroesophageal reflux following esophageal atresia repair. J Pediatr Surg 1993; 28(1): 53–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koivusalo A I, Pakarinen M P, Lindahl H G, Rintala R J. Endoscopic surveillance after repair of oesophageal atresia: longitudinal study in 209 patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 62(4): 562–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jönsson L, Dellenmark-Blom M, Enoksson O et al. Long-term effectiveness of antireflux surgery in esophageal atresia patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2019; 29(6): 521–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yasuda J L, Clark S J, Staffa S J et al. Esophagitis in pediatric esophageal atresia: acid may not always be the issue. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019; 69(2): 163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pellegrino S A, King S K, McLeod E et al. Impact of esophageal atresia on the success of fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr 2018; 198: 60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tambucci R, Isoldi S, Angelino G et al. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease 1 year after esophageal atresia repair: paradigms lost from a single snapshot? J Pediatr 2021; 228: 155–63.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donoso F, Lilja H E. Risk factors for anastomotic strictures after esophageal atresia repair: prophylactic proton pump inhibitors do not reduce the incidence of strictures. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2017; 27(1): 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stenström P, Anderberg M, Börjesson A, Arnbjornsson E. Prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors as stricture prophylaxis in infants with reconstructed esophageal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2017; 27(02): 192–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Righini Grunder F, Petit L M, Ezri J et al. Should proton pump inhibitors be systematically prescribed in patients with esophageal atresia after surgical repair? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019; 69(1): 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loots C, van Herwaarden M Y, Benninga M A, VanderZee D C, van Wijk M P, Omari T I. Gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal function, gastric emptying, and the relationship to dysphagia before and after antireflux surgery in children. J Pediatr 2013; 162(3): 566–73.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Omari T, Connor F, McCall L et al. A study of dysphagia symptoms and esophageal body function in children undergoing anti-reflux surgery. United European Gastroenterol J 2018; 6(6): 819–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.