Abstract

Here, we report ribosomal construction of thioether-macrocyclic α/β3-peptide libraries in which β-homoglycine, β-homoalanine, β-homophenylglycine, and β-homoglutamine are introduced by genetic code reprogramming. The libraries were applied to the RaPID (Random nonstandard Peptides Integrated Discovery) selection against human EGFR to obtain PPI (protein–protein interaction) inhibitors. The resulting peptides contained up to five β3-amino acid (β3AA) residues and exhibited outstanding binding affinity, PPI inhibitory activity, and proteolytic stability, which were attributed to the β3AAs included in the peptides. This showcase work has demonstrated that the use of such β3AAs enhances the drug-like properties of peptides, providing a unique platform for the discovery of de novo macrocycles against a protein of interest.

Introduction

Peptides containing β-amino acids often display unique and strong folding abilities and therefore are referred to as foldamers.1−3 Not only peptides solely consisting of β-amino acids (β-peptides) but also the ones containing both α- and β-amino acids (α/β-peptides) show stronger folding abilities compared to α-peptides. Consequently, α/β-peptides exhibit stable helical propensities as well as turn-inducing abilities to form γ-turns and β-turns.1,4−11 Owing to the self-folding ability of such α/β-peptides, they are able to gain a favorable entropic effect compared to α-peptides and thereby potent binding affinity to target protein could be expected.11 Moreover, α/β-peptides generally have superior proteolytic stability than α-peptides because of the lack of or poor digesting ability of naturally occurring peptidases against peptide bonds involving β-amino acid(s).12−15

In order to take advantage of such characteristics of β-amino acids, efforts to enhance proteolytic stability of existing peptide drugs by replacing their α-amino acids with β-amino acids has been reported.16,17 However, in many cases, such a substituted peptide exhibits a reduced binding affinity to the target molecule in exchange for enhanced proteolytic stability. This is likely because the insertion of one extra methylene bond in the peptide main chain disrupts the parental binding mode. Alternatively, if we were able to conduct the selection campaigns of active species of α/β-peptides from scratch using their mass library, we could access de novo α/β-peptides bearing high binding affinity and proteolytic stability.

Although ribosomal incorporation of β-amino acids had been previously demonstrated, their incorporation efficiency was much lower than that of α-amino acids; therefore, consecutive and/or alternate incorporation of β-amino acids had been nearly impossible.18−22 However, this issue has been recently solved by the development of an engineered tRNA, named tRNAPro1E2, having the unique T-stem and D-arm sequences that improve the binding affinities to EF-Tu and EF-P, respectively.23−27 Consequently, the β-aminoacyl-tRNAPro1E2 complexed with EF-Tu can be efficiently delivered and accommodated to the ribosome A-site, and its slow elongation rate is compensated by the binding of EF-P to the ribosome E site. Thus, it enables alternating and even consecutive incorporation of β-amino acids.

Encouraged by the establishment of the tRNAPro1E2/EF-P system, we have recently constructed a macrocyclic α/β-peptide library containing three kinds of cyclic β2,3-amino acids (cβAA), (1S,2S)-2-ACHC, (1S,2S)-2-ACPC, and (1R,2R)-2-ACPC, and performed the RaPID (Random nonstandard Peptides Integrated Discovery) selection against human FXIIa and IFNGR1.26 We have then witnessed that one of the active thioether-macrocyclic α/β2,3-peptides containing two (1S,2S)-2-ACHC residues, whose co-crystal structure has been solved, forms a foldamer-like structure, in which the respective residues make not only β- and γ-turns but also direct contact of their cyclohexane ring with residues of FXIIa. This observation has motivated us to further explore different sequence space available in other α/β-peptides. Here, we report the construction of macrocyclic α/β3-peptide libraries consisting of β3-amino acids (β3AAs) with various sidechains at the β3 position applying to the RaPID selection.

Results

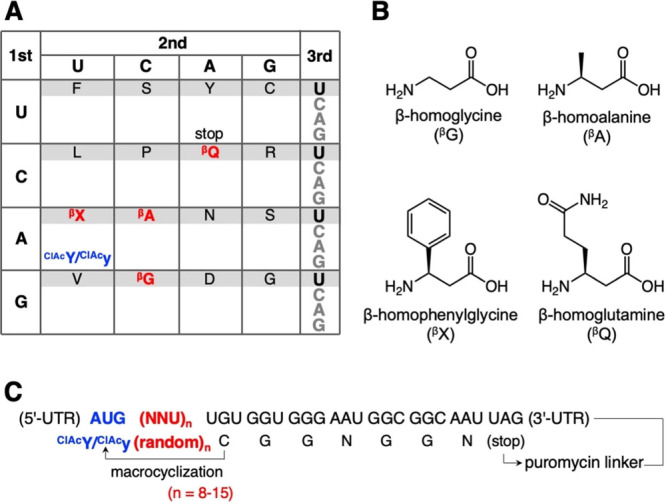

In order to construct macrocyclic α/β3-peptide libraries, we introduced four kinds of β3AAs, β-homoglycine (βG), β-homoalanine (βA), β-homophenylglycine (βX), and β-homoglutamine (βQ) at GCU, ACU, AUU, and CAU codons using precharged βG-tRNAPro1E2GGC, βA-tRNAPro1E2GGU, βX-tRNAPro1E2GAU, and βQ-tRNAPro1E2GUG, respectively (Figure 1A,B, Supplementary Figure S1A, and Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the initiator AUG codon was reprogrammed to N-(2-chloroacetyl)-l- or d-tyrosine (ClAcY or ClAcy) by using precharged ClAcY- or ClAcy-tRNAfMetCAU (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure S1B). The libraries initiated with ClAcY and ClAcy were referred to as L-library and D-library, respectively. Precharge of those nonproteinogenic amino acids onto tRNAs was performed by using flexizymes (see the Supplementary Methods section for details).28 Upon translation of the peptide libraries, a nonreducible thioether bond was spontaneously formed between the N-terminal ClAc group and a sulfhydryl group of a downstream Cys (C), thereby giving a thioether-macrocyclic scaffold. Thioether macrocyclization takes place in nearly quantitative manners regardless of the length and sequence of peptides.29,30 The template mRNA had an initiator AUG codon for ClAcY/ClAcy, followed by a repeat of 8 to 15 random NNU codons, a UGU codon for C, a GGU-GGG-AAU-GGC-GGC-AAU for (GGN)2 as a spacer, and a stop codon UAG (Figure 1C). A puromycin linker was ligated at the 3′-end of mRNA for the connection between the mRNA and the C-terminus of the corresponding peptide. For the construction of the reprogrammed translation system, referred to as the Flexible In vitro Translation (FIT) system,28 unnecessary amino acids and the corresponding ARSs, whose codons were reprogrammed (M, A, T, I, and H) or not assigned by NNU codons (Q, K, E, and W), were omitted; 11 proteinogenic amino acids (F, L, V, S, P, Y, N, D, C, R, and G) and the corresponding ARSs were included.

Figure 1.

Construct of the macrocyclic α/β3-peptide libraries bearing four kinds of β3AAs. (A) Reprogrammed genetic code used for translation of the peptide libraries. β3-amino acids and the ClAc initiator building blocks are indicated by red and blue, respectively. (B) Structures of the β3AAs used in this study. (C) Sequences of the mRNA library and the corresponding peptide library.

The RaPID selection of the α/β3-macrocyclic peptide libraries was performed against human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (hEGFR) as a target protein, which is a cancer biomarker (Supplementary Figure S2A).31 The mRNA-peptide conjugates were reverse-transcribed into mRNA-cDNA-peptide complexes and applied to the biotin-tagged hEGFR immobilized on streptavidin magnetic beads, which we call “positive selection”. The bound fractions were recovered and amplified by PCR into a cDNA library for the next round. For the second round and after, the mRNA-cDNA-peptide complexes were first applied to naked magnetic beads without hEGFR to remove bead-binding nonspecific peptides, which we call “negative selection,” prior to the positive selection. The series of the in vitro selection process were repeated for five rounds, and the recovery rate of cDNA was measured by qPCR at each round (Supplementary Figure S2B). Then, cDNA sequences and the corresponding peptide sequences at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th rounds were analyzed by next-generation sequencing. Supplementary Table S2 summarizes the top 100 most abundant peptide sequences at the 5th round and their read frequencies at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th rounds. Summation of the read frequencies for the top 100 peptides increased from 3.7% (3rd round) to 96.6% (5th round) for the L-library and from 4.3% (3rd round) to 87.6% (5th round) for the D-library, showing the enrichment of hEGFR-binding species at the later rounds. We chose four candidate peptides each from the L- and D-library for further characterizations, considering their high read frequencies and numbers of β3AAs (Table 1, L1β, L2β, L3β, L4β, D1β, D2β, D3β, and D4β). For chemical synthesis of these peptides, the C-terminal GNGGN region of the (GGN)2 spacer was omitted. If there are two or more Cys residues in the nascent peptide sequences, the nearest Cys most likely reacts with the N-terminal ClAc group to form a thioether bond, for example, those in L3β and D2β.30 The remaining Cys residues that were not utilized for macrocyclization were substituted with Ser for chemical synthesis (Table 1, positions 12 and 16 in L3β and D2β, respectively). The identities of chemically synthesized peptides were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (Supplementary Figure S3).

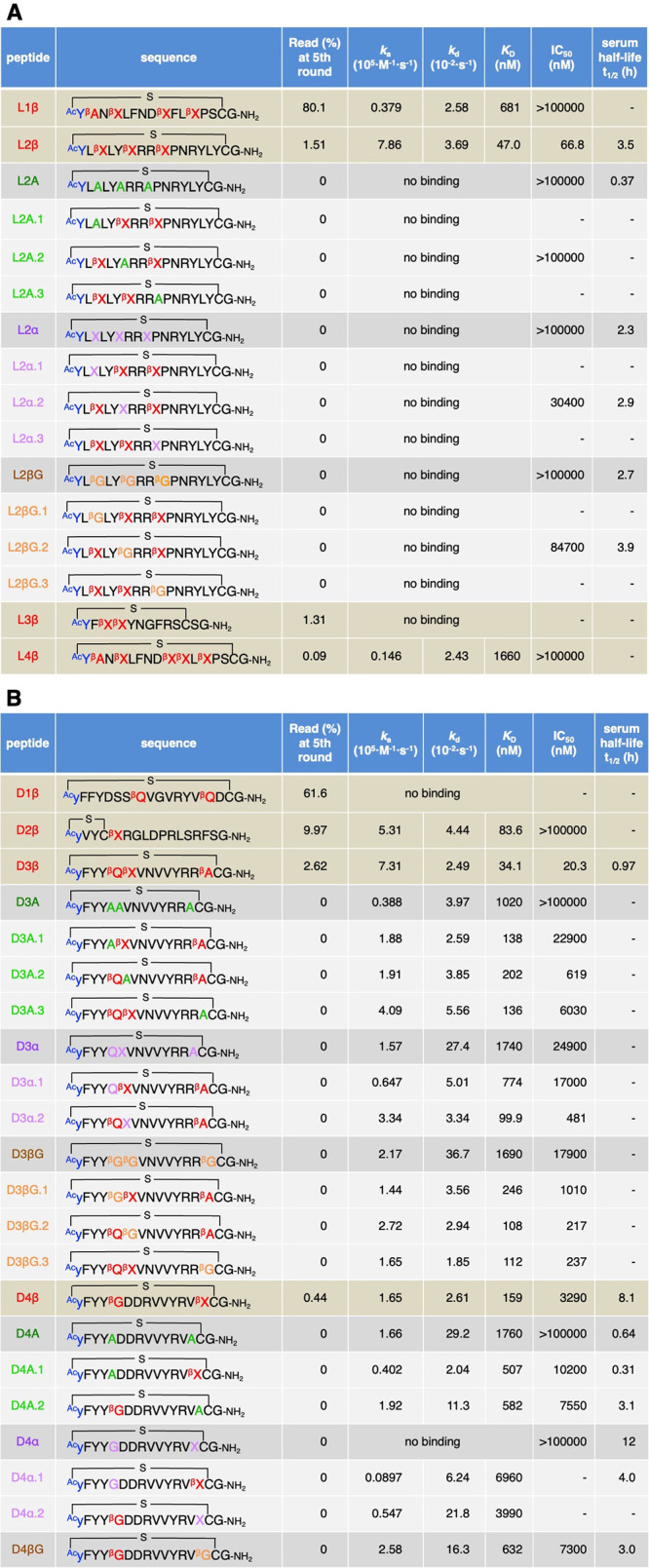

Table 1. Characterization of hEGFR-Binding Peptidesa.

Peptides obtained from L-library (A) and D-library (B). Sequences of the peptides, their read frequency at the 5th round, ka, kd, KD, IC50, and serum half-lives (t1/2) are summarized. See also Supplementary Figure S4, Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S6, Figure 3 for the raw data of SPR, inhibition assay, and serum stability assay, respectively.

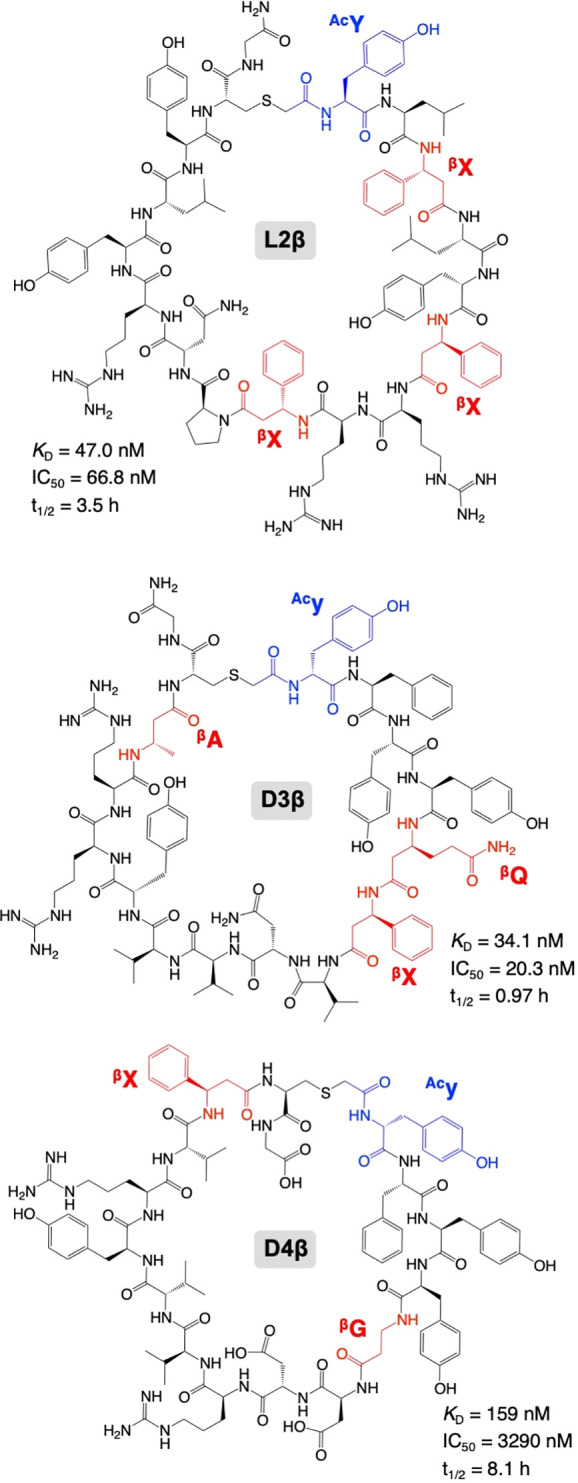

The binding affinities of the eight candidate peptides against hEGFR were evaluated by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S4A, L1–4β and D1–4β). All peptides except for L3β and D1β exhibited binding affinity to hEGFR. Notably, L2β, D2β, D3β, and D4β showed potent binding affinities to the target protein with the KD values of 47.0, 83.6, 34.1, and 159 nM, respectively. Contributions of β3AAs to the affinity of peptides, L2β, D3β, and D4β, were evaluated by their full or partial mutations. We prepared three types of mutants: (1) Ala mutants, (2) backbone-shortening mutants, and (3) sidechain-deletion mutants, where the β3AAs were replaced by (1) A, (2) cognate α-amino acids bearing the same side chain, and (3) βG, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S5, A series, α series, and βG series, respectively). Consequently, all L2β mutants showed no binding affinity in the SPR assay (Table 1A and Supplementary Figure S4B, L2A, L2A.1–3, L2α, L2α.1–3, L2βG, and L2βG.1–3), indicating that all of the three βX residues of L2β played critical roles in binding. Likewise, mutants of D3β and D4β showed 3- to 50-fold weaker affinities than their parental peptides (Table 1B and Supplementary Figure S4C, D). Full mutations of β3AAs in D3β and D4β (D3A, D3α, D3βG, D4A, and D4α) resulted in significantly weaker affinities than their partial mutations (D3A.1–3, D3α.1–2, D3βG.1–3, D4A.1–2, and D4α.1–2). These results also indicate that all β3AAs in D3β and D4β contribute to their binding activity (βQ, βX, and βA in D3β and βG and βX in D4β). Not only the longer backbone of the β3AAs but also their sidechains are indispensable for the binding affinity.

To further evaluate the contribution of β3AAs to the affinity, three additional candidate peptides that lacked β3AA were chosen and chemically synthesized for the SPR assay (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, L5, D5, and D6). Consequently, these peptides resulted in relatively low or virtually no binding affinity (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure S4A, KD = 1950 and 361 nM for L5 and D5, and no binding for D6). The lower read (%) of these peptides than those of L1–4β and D1–4β indicate that such peptides lacking β3AAs were not preferentially selected during the RaPID screening because of their weaker affinities (Supplementary Table S2, 0.06, 0.05, and 0.03% for L5, D5, and D6, respectively). Given the incorporation of β3AA is much less efficient than that of the canonical α-amino acids, translation yields of peptides bearing more β3AAs should be lower. Thus, there should be a negative selection pressure for β3-peptides during the RaPID. Nevertheless, they dominated over the peptides lacking β3AA at the 5th round of selection, indicating the contribution of β3AA to binding affinity.

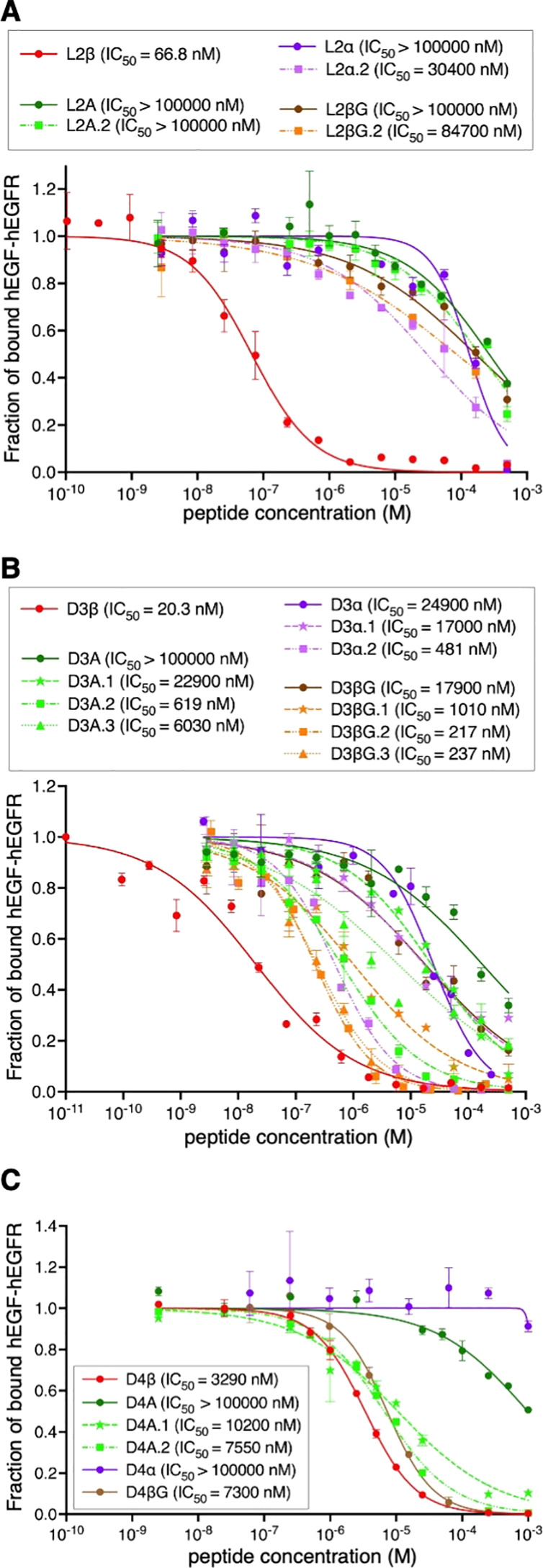

We next analyzed the PPI inhibitory activities of the parent peptides against hEGF–hEGFR interaction by means of the AlphaLISA technology, by which a fraction of bound hEGF–hEGFR was quantified (Table 1, Supplementary Table S3, Figure 2, and Supplementary Figure S6, L1β, L2β, L4β, L5, D2β, D3β, D4β, D5, and D6).32−34 Among them, L2β, D3β, D4β, and D5 showed inhibitory activities with IC50 values of 66.8, 20.3, 3290, and 1200 nM, respectively. In contrast, L1β, L4β, D2β, and L5 displayed no inhibitory activity, even though they could bind hEGFR in the SPR experiment, indicating that they bind ineffective site(s) for the PPI inhibition. L3β, D1β, and D6 were not tested with an inhibition assay because they had no binding affinity. To evaluate the contribution of β3AAs in L2β, D3β, and D4β, the inhibitory activities of their Ala mutants, backbone-shortening mutants, and sidechain-deletion mutants were also evaluated. In the case of L2β-based mutants, L2A, L2A.1, L2α, and L2βG showed virtually no inhibitory activity (Table 1A, >100000 nM). L2α.2 and L2βG.2 showed 460- and 1270-fold increase of IC50 compared to the parent L2β. Thus, βX residues of L2β are indispensable for the inhibitory activity. For the D3-based mutants, all-Ala, all-α, and all-βG mutants exhibited 1000-fold or higher IC50 values (Table 1B, D3A, D3α, and D3βG), whereas 10- to 1000-fold increase for partial mutants (Table 1B, D3A.1–3, D3α.1–2, and D3βG.1–3). Substitution of βQ with A, Q, and βG resulted in relatively higher IC50 compared to the substitution of βX and βA, indicating the importance of βQ for the activity. For the D4β-based mutants, D4A and D4α showed complete loss of the activity, whereas D4βG resulted in only 2.2-fold increase of IC50 (Table 1B). This is likely because only one substitution, βX to βG, was introduced in D4βG because the other β3AA in D4β was originally βG. Partial Ala mutants, D4A.1–2, also showed comparable values (Table 1B, 2.3- and 3.1-fold increase of IC50). Overall, we could confirm that all of the β3AA residues found in L2β, D3β, and D4β contributed to their inhibitory activities. In addition, both of the longer backbones and the sidechains of these β3AAs are requisite.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory activity of peptides against hEGF–hEGFR interaction. The fraction of bound hEGF–hEGFR was estimated by the intensity of 615 nm emission using AlphaLISA. The value in the absence of peptide is defined as 1. n = 3. See also Supplementary Figure S6 for the results of L1β, L4β, D2β, L5, and D5.

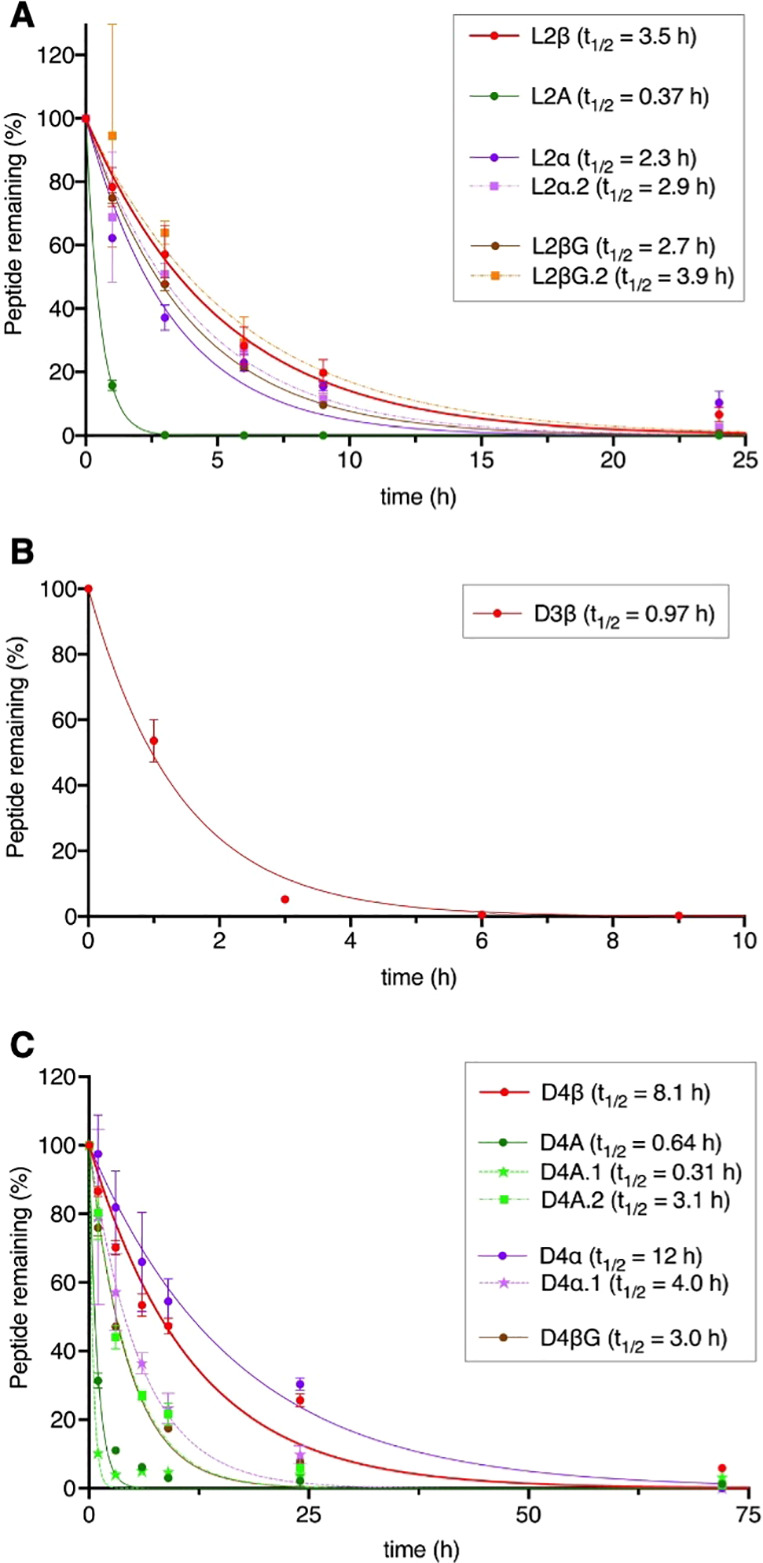

Finally, we analyzed the proteolytic stability of L2β, D3β, and D4β. These peptides were incubated in human serum at 37 °C for up to 72 h, and their half-lives (t1/2) were evaluated by LC/MS (Table 1 and Figure 3, 3.5, 0.97, and 8.1 h for L2β, D3β, and D4β). To evaluate the contributions of β3AAs to the stability, Ala mutants, backbone-shortening mutants, and sidechain-deletion mutants of L2β and D4β were also tested. Among the L2β mutants, L2A exhibited approximately 10-fold lower t1/2 value than the parent L2β (0.37 h vs 3.5 h), showing that β3AAs commit an increase in their proteolytic stability. On the other hand, backbone-shortening mutants and sidechain-deletion mutants showed relatively smaller change of stability (Table 1, 2.3, 2.9, 2.7, and 3.9 h for L2α, L2α.2, L2βG, and L2βG.2). Because X and βG are noncanonical amino acids, proteases would not efficiently recognize these residues for proteolysis. Thus, substitution of the original βX with X and βG for backbone-shortening and sidechain-deletion would not lead to large decrease of the proteolytic stability of peptides. In the case of D4β mutants, D4A.1 showed a 26-fold lower t1/2 value than the parent D4β (0.31 h vs 8.1 h), indicating the possibility that βG at the fifth position contributes to the proteolytic stability; However, substitution of this βG with G resulted in only 2-fold decrease of the stability (4.0 h for D4α.1). Substitution of βX at the 14th position with A also showed only 2.6-fold decrease (3.1 h for D4A.2). Therefore, contribution of β3AAs in this peptide to the proteolytic stability turned out to be modest.

Figure 3.

Proteolytic stability of peptides. L2β, L2A, D4β, and L4A were incubated in human serum for up to 72 h and the percentages of remaining peptides were estimated by LC/MS.

Discussion

This is the first study ever, to the best of our knowledge, that succeeded in ribosomal synthesis and application of macrocyclic peptide libraries containing multiple kinds of β3AAs. L2β, D3β, and D4β uncovered in this study show potent binding affinity, PPI inhibitory activity, and improved proteolytic stability owing to the presence of β3AAs (βG, βA, βX, and βQ) in these peptides (Table 1 and Figure 4). We have also recently reported the RaPID selection against the same hEGFR target using a d/l-hybrid macrocyclic peptide library bearing five kinds of d-α-amino acids (DAA), yielding two potent peptides, 2D and 18D, containing 5 and 6 DAAs, respectively.34 Their binding affinity and PPI inhibitory activity were KD values of 523 and 998 nM, and IC50 of 2170 and 320 μM, respectively. In comparison, L2β, D3β, and D4β exhibited approximately 10-fold stronger binding affinity (KD = 47.0, 34.1, and 159 nM) and 100–100000-fold stronger inhibitory activity (IC50 = 66.8, 20.3, and 3290 nM). Although we do not yet know the exact reason why some peptides exhibit inconsistent values between KD and IC50, it is possible that they bind slightly to an off-site of the hEGF–hEGFR interface or an allosteric site. Nevertheless, the observed PPI inhibitory activity of L2β, D3β, and D4β superior to 2D and 18D could suggest that the stronger folding ability contributed by β3AAs than DAAs could dictate more potent binding affinity because of the entropic effect. In addition, incorporation of β3AAs improved their proteolytic stability by up to 10-fold. These results showed the advantage of using macrocyclic α/β3-peptide library for screening stronger inhibitors with high proteolytic stability. Although ribosomal incorporation of cβAAs, such as 2-ACHC, has also been previously demonstrated,26 substitution of canonical α-amino acids with cβAAs would lead to loss of sidechain functionality. On the other hand, in the case of substitution with β3AA, the backbone can be extended without losing sidechain functionalities. In fact, substitution of β3AAs found in L2β, D3β, and D4β with βG resulted in significant decrease of binding affinities and inhibitory activities, showing the importance of sidechain functionalities of these β3AAs.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of representative hEGFR inhibitor peptides.

Many of the candidate peptides obtained by the sequencing had consecutive and/or alternate incorporation of β3AAs. Out of the top 200 peptide sequences (Supplementary Table S2, Top 100 each from L- and D-library), 76 peptides had consecutive/alternate β3AAs in their sequences. For instance, L3β, L4β, and D3β have consecutive β3AAs, and L1β and L4β have alternate β3AAs (Table 1). Such consecutive and alternate incorporation of β3AAs had been previously considered formidable, but the use of an engineered tRNA, tRNAPro1E2, paired with EF-P, has made it possible. This strategy enables us to set up the selection campaigns using not only α/β3-peptide libraries but also the combination of α/β3/β2,3-peptide libraries, giving us nearly infinite opportunities for the discovery of macrocyclic peptide drugs against protein targets of choice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (22H00439) and Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering) (21K18233) to T.K., and Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (20H05618) to H.S.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c07624.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Appella D. H.; Christianson L. A.; Karle I. L.; Powell D. R.; Gellman S. H. β-Peptide foldamers: robust helix formation in a new family of β-amino acid oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 13071–13072. 10.1021/ja963290l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gellman S. H. Foldamers: a manifesto. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 173–180. 10.1021/ar960298r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D. J.; Mio M. J.; Prince R. B.; Hughes T. S.; Moore J. S. A field guide to foldamers. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3893–4012. 10.1021/cr990120t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appella D. H.; Christianson L. A.; Klein D. A.; Powell D. R.; Huang X.; Barchi J. J.; Gellman S. H. Residue-based control of helix shape in β-peptide oligomers. Nature 1997, 387, 381–384. 10.1038/387381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann F.; Müller A.; Koksch M.; Müller G.; Sewald N. Are β-amino acids γ-turn mimetics? Exploring a new design principle for bioactive cyclopeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 12009–12010. 10.1021/ja0016001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strijowski U.; Sewald N. Structural properties of cyclic peptides containing cis- or trans-2-aminocyclohexane carboxylic acid. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 1105–1109. 10.1039/b312432k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malešević M.; Majer Z.; Vass E.; Huber T.; Strijowski U.; Hollósi M.; Sewald N. Spectroscopic detection of pseudo-turns in homodetic cyclic penta- and hexapeptides comprising β-homoproline. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2006, 12, 165–177. 10.1007/s10989-006-9013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guthohrlein E. W.; Malesevic M.; Majer Z.; Sewald N. Secondary structure inducing potential of β-amino acids: torsion angle clustering facilitates comparison and analysis of the conformation during MD trajectories. Biopolymers 2007, 88, 829–839. 10.1002/bip.20859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Guzei I. A.; Spencer L. C.; Gellman S. H. Crystallographic characterization of helical secondary structures in α/β-peptides with 1:1 residue alternation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6544–6550. 10.1021/ja800355p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Guzei I. A.; Spencer L. C.; Gellman S. H. Crystallographic characterization of helical secondary structures in 2:1 and 1:2 α/β-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2917–2924. 10.1021/ja808168y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrele C.; Martinek T. A.; Reiser O.; Berlicki Ł. Peptides containing β-amino acid patterns: challenges and successes in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9718–9739. 10.1021/jm5010896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frackenpohl J.; Arvidsson P. I.; Schreiber J. V.; Seebach D. The outstanding biological stability of β- and γ-peptides toward proteolytic enzymes: an in vitro investigation with fifteen peptidases. ChemBioChem 2001, 2, 445–455. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebach D.; Rueping M.; Arvidsson P. I.; Kimmerlin T.; Micuch P.; Noti C.; Langenegger D.; Hoyer D. Linear, Peptidase-resistant β2/β3-di- and α/β3-tetrapeptide derivatives with nanomolar affinities to a human somatostatin receptor, preliminary communication. Helv. Chim. Acta 2001, 84, 3503–3510. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopi H. N.; Ravindra G.; Pal P. P.; Pattanaik P.; Balaram H.; Balaram P. Proteolytic stability of β-peptide bonds probed using quenched fluorescent substrates incorporating a hemoglobin cleavage site. FEBS Lett. 2003, 535, 175–178. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook D. F.; Bindschädler P.; Mahajan Y. R.; Šebesta R.; Kast P.; Seebach D. The proteolytic stability of ‘designed’ β-peptides containing α-peptide-bond mimics and of mixed α,β-peptides: application to the construction of MHC-binding peptides. Chem. Biodivers. 2005, 2, 591–632. 10.1002/cbdv.200590039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gademann K.; Ernst M.; Hoyer D.; Seebach D. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a cyclo-β-tetrapeptide as a somatostatin analogue. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1223–1226. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar M.-I.; Purcell A. W.; Devi R.; Lew R.; Rossjohn J.; Smith A. I.; Perlmutter P. β-Amino acid-containing hybrid peptides—new opportunities in peptidomimetics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2884. 10.1039/b708507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedkova L. M.; Fahmi N. E.; Paul R.; del Rosario M.; Zhang L.; Chen S.; Feder G.; Hecht S. M. β-Puromycin selection of modified ribosomes for in vitro incorporation of β-amino acids. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 401–415. 10.1021/bi2016124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maini R.; Nguyen D. T.; Chen S.; Dedkova L. M.; Chowdhury S. R.; Alcala-Torano R.; Hecht S. M. Incorporation of β-amino acids into dihydrofolate reductase by ribosomes having modifications in the peptidyltransferase center. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1088–1096. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maini R.; Chowdhury S. R.; Dedkova L. M.; Roy B.; Daskalova S. M.; Paul R.; Chen S.; Hecht S. M. Protein synthesis with ribosomes selected for the incorporation of β-amino acids. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 3694–3706. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekster C. M.; Robertson W. E.; Walker A. S.; Soll D.; Schepartz A. In vivo biosynthesis of a β-amino acid-containing protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5194–5197. 10.1021/jacs.6b01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T.; Goto Y.; Suga H.; Murakami H. Ribosomal synthesis of peptides with multiple β-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1962–1969. 10.1021/jacs.5b12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T.; Wohlgemuth I.; Nagano M.; Rodnina M. V.; Suga H. Essential structural elements in tRNAPro for EF-P-mediated alleviation of translation stalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11657. 10.1038/ncomms11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T.; Iwane Y.; Suga H. Logical engineering of D-arm and T-stem of tRNA that enhances D-amino acid incorporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12601–12610. 10.1093/nar/gkx1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T.; Suga H. Ribosomal incorporation of consecutive β-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12159–12167. 10.1021/jacs.8b07247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T.; Sengoku T.; Hirata K.; Ogata K.; Suga H. Ribosomal synthesis and de novo discovery of bioactive foldamer peptides containing cyclic β-amino acids. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 1081–1088. 10.1038/s41557-020-0525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh T.; Suga H. Ribosomal elongation of aminobenzoic acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16518–16522. 10.1021/jacs.0c05765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y.; Shoji I.; Miyagawa S.; Kawakami T.; Katoh T.; Goto Y.; Suga H. Natural product-like macrocyclic N-methyl-peptide inhibitors against a ubiquitin ligase uncovered from a ribosome-expressed de novo library. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1562–1570. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y.; Ohta A.; Sako Y.; Yamagishi Y.; Murakami H.; Suga H. Reprogramming the translation initiation for the synthesis of physiologically stable cyclic peptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 120–129. 10.1021/cb700233t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K.; Goto Y.; Katoh T.; Suga H. Selective thioether macrocyclization of peptides having the N-terminal 2-chloroacetyl group and competing two or three cysteine residues in translation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 5783. 10.1039/c2ob25306b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loong H. H.; Kwan S. S.; Mok T. S.; Lau Y. M. Therapeutic strategies in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 58. 10.1007/s11864-018-0570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeld-Sevigny M. AlphaLISA immunoassay platform— the “no-wash” high-throughput alternative to ELISA. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2009, 7, 90–92. 10.1089/adt.2009.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasgar A.; Jadhav A.; Simeonov A.; Coussens N. P. AlphaScreen-based assays: ultra-high-throughput screening for small-molecule inhibitors of challenging enzymes and protein-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1439, 77–98. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3673-1_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi S.; Katoh T.; Yin Y.; Yamada M.; Kawai M.; Suga H. In vitro selection of macrocyclic D/L-hybrid peptides against human EGFR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5680–5684. 10.1021/jacs.1c02593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.