| Diretriz da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia sobre a Análise e Emissão de Laudos Eletrocardiográficos – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| O relatório abaixo lista as declarações de interesse conforme relatadas à SBC pelos especialistas durante o período de desenvolvimento deste posicionamento, 2021. | |

| Especialista | Tipo de relacionamento com a indústria |

| Acácio Fernandes Cardoso | Nada a ser declarado |

| Adail Paixao Almeida | Nada a ser declarado |

| Alfredo José da Fonseca | Nada a ser declarado |

| Andrés R. Pérez-Riera | Nada a ser declarado |

| Antonio Luiz Pinho Ribeiro |

|

| Braulio Luna Filho | Nada a ser declarado |

| Bruna Affonso Madaloso |

|

| Carlos Alberto Pastore | Nada a ser declarado |

| Carlos Alberto Rodrigues de Oliveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Cesar José Grupi | Nada a ser declarado |

| Claudio Pinho |

|

| Dalmo Antônio Ribeiro Moreira |

|

| Elisabeth Kaiser | Nada a ser declarado |

| Epotamenides Maria Good God | Nada a ser declarado |

| Francisco Faustino de Albuquerque Carneiro de França | Nada a ser declarado |

| Gabriela Miana de Mattos Paixão | Nada a ser declarado |

| Gilson Soares Feitosa Filho | Nada a ser declarado |

| Horacio Gomes Pereira Filho | Nada a ser declarado |

| João A Pimenta de Almeida | Nada a ser declarado |

| Jose Claudio Lupi Kruse | Nada a ser declarado |

| José Grindler | Nada a ser declarado |

| Jose Luis Aziz |

|

| Marcelo Garcia Leal | Nada a ser declarado |

| Marcos Sleiman Molina |

|

| Mirella Facin | Nada a ser declarado |

| Nancy Maria Martins De Oliveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Nelson Samesima | Nada a ser declarado |

| Patricia Alves de Oliveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Paulo César Ribeiro Sanches | Nada a ser declarado |

| Ricardo Alkmim Teixeira |

|

| Severiano Atanes Netto | Nada a ser declarado |

Sumário

Introdução

1. Normatização para Análise e Emissão do

Laudo Eletrocardiográfico

1.1. Normatização para Análise Eletrocardiográfica

1.2. O Laudo Eletrocardiográfico

1.2.1. Laudo Descritivo

1.2.2. Laudo Conclusivo

1.2.3. Laudo Automatizado

1.2.4. Laudo Via Internet

2. Avaliação da Qualidade Técnica do Traçado

2.1. Critérios de Avaliação Técnica dos Traçados

2.1.1. Calibração do Eletrocardiógrafo

2.1.2. Troca de Eletrodos

2.1.2.1. Posicionamento Trocado dos Eletrodos

2.1.2.1.1. Eletrodos dos MMSS Trocados entre Si

2.1.2.2. Eletrodo dos MMII trocado por um eletrodo de um dos MMSS

2.1.2.3. Troca de Eletrodos entre Braço Esquerdo e Perna Esquerda

2.1.2.4. Troca de Eletrodos Precordiais

2.1.2.5. Eletrodos V1 e V2 Mal Posicionados

2.1.3. Outras Interferências

2.1.3.1. Tremores Musculares

2.1.3.2. Neuroestimulação

2.1.3.3. Frio, Febre, Soluços, Agitação Psicomotora

2.1.3.4. “Grande Eletrodo” Precordial

2.1.3.5. Oscilação da Linha de Base

2.1.3.6. Outras Interferências Elétricas e Eletromagnéticas

2.1.3.7. Alterações Decorrentes de Funcionamento Inadequado de

Softwares e Sistemas de Aquisição de Sinais Eletrocardiográficos

Computadorizados

3. A Análise do Ritmo Cardíaco

3.1. Análise da Onda P, Frequência Cardíaca e Ritmo

3.1.1. Definição do Ritmo Sinusal (RS)

3.1.2. Frequência da Onda P Sinusal

3.2. Análise das Alterações de Ritmo Supraventricular

3.2.1. Definição de Arritmia Cardíaca

3.2.2. Arritmia Supraventricular

3.2.3. Presença de Onda P Sinusal

3.2.3.1. Arritmia Sinusal (AS)

3.2.3.2. Bradicardia Sinusal (BS)

3.2.3.3. Bloqueio Sinoatrial de Segundo Grau

3.2.3.4. Bloqueios Interatriais (BIA)

3.2.3.5. Taquicardia Sinusal (TS)

3.2.4. Ausência de Onda P Antes do QRS

3.2.4.1. Fibrilação Atrial (FA)

3.2.4.2. Flutter Atrial

3.2.4.3. Ritmo Juncional

3.2.4.4. Extrassístole Juncional

3.2.4.5. Taquicardia por Reentrada Nodal Comum (TRN)

3.2.4.6. Taquicardia por Reentrada Atrioventricular Ortodrômica (TRAV)

3.2.5. Presença da Onda P Não Sinusal Antes do QRS

3.2.5.1. Ritmo Atrial Ectópico (RAE)

3.2.5.2. Ritmo Atrial Multifocal (RAM)

3.2.5.3. Ritmo Juncional

3.2.5.4. Batimento de Escape Atrial

3.2.5.5. Extrassístole Atrial (EA)

3.2.5.6. Extrassístole Atrial Bloqueada ou Não Conduzida

3.2.5.7. Taquicardia Atrial (TA)

3.2.5.8. Taquicardia Atrial Multifocal (TAMF)

3.2.5.9. Taquicardia por Reentrada Nodal Incomum

3.2.5.10. Taquicardia de Coumel

3.2.6. Pausas

3.2.6.1. Parada Sinusal (PS)

3.2.6.2. Disfunção do Nó Sinusal (DNS)

3.2.7. Classificação de Taquicardias Supraventriculares Baseadas no

Intervalo RP

3.2.8. Arritmias Supraventriculares com Complexo QRS Alargado

3.2.8.1. Aberrância de Condução

3.2.8.2. Extrassístole Atrial com Aberrância de Condução

3.2.8.3. Taquicardia Supraventricular com Aberrância de Condução

3.2.8.4. Taquicardia por Reentrada Atrioventricular Antidrômica

4. Condução Atrioventricular

4.1. Definição da Relação Atrioventricular (AV) Normal

4.1.1. Atraso da Condução Atrioventricular (AV)

4.1.1.1. Bloqueio AV de Primeiro Grau

4.1.1.2. Bloqueio AV de Segundo Grau Tipo I (Mobitz I)

4.1.1.3. Bloqueio AV de Segundo Grau Tipo II (Mobitz II)

4.1.1.4. Bloqueio AV 2:1

4.1.1.5. Bloqueio AV Avançado ou de Alto Grau

4.1.1.6. Bloqueio AV do Terceiro Grau ou BAV Total (BAVT)

4.1.1.7. Bloqueio AV Paroxístico

4.1.2. Pré-Excitação Ventricular

4.1.3. Outros Mecanismos de Alteração da Relação AV Normal

4.1.3.1. Dissociação AV

4.1.3.2. Ativação Atrial Retrógrada

5. Análise da Ativação Ventricular

5.1. Ativação Ventricular Normal

5.1.1. Definição do QRS Normal

5.1.2. Eixo Elétrico Normal no Plano Frontal

5.1.3. Ativação Ventricular Normal no Plano Horizontal

5.1.4. Análise das Alterações de Ritmo Ventricular

5.1.4.1. Definição de Arritmia Cardíaca

5.1.4.2. Arritmia Ventricular

5.1.4.3. Análise das Arritmias Ventriculares

5.1.4.3.1. Extrassístole Ventricular (EV)

5.1.4.3.2. Batimento(s) de Escape Ventricular(es)

5.1.4.3.3. Ritmo de Escape Ventricular – Ritmo Idioventricular

5.1.4.3.4. Ritmo Idioventricular Acelerado (RIVA)

5.1.4.3.5. Taquicardia Ventricular (TV)

5.1.4.3.5.1. Taquicardia Ventricular Monomórfica

5.1.4.3.5.2. Taquicardia Ventricular Polimórfica (TVP)

5.1.4.3.5.3. Taquicardia Ventricular Tipo Torsade des Pointes (TdP)

5.1.4.3.5.4. Taquicardia Ventricular Bidirecional

5.1.4.3.5.5. Quanto à Duração

5.1.4.3.6. Batimento de Fusão

5.1.4.3.7. Batimento com Captura Supraventricular Durante

Ritmo Idioventricular

5.1.4.3.8. Parassístole Ventricular (PV)

5.1.4.3.9. Fibrilação Ventricular (FV)

5.1.4.4. Critérios de Diferenciação entre as Taquicardias de

Complexo QRS Alargado

6. Sobrecargas das Câmaras Cardíacas

6.1. Sobrecargas Atriais

6.1.1. Sobrecarga Atrial Esquerda (SAE)

6.1.2. Sobrecarga Atrial Direita (SAD)

6.1.3. Sobrecarga Biatrial (SBA)

6.1.4. Sobrecarga Ventricular Esquerda (SVE)

6.1.4.1. Critérios de Romhilt-Estes

6.1.4.2. Índice de Sokolow Lyon

6.1.4.3. Índice de Cornell

6.1.4.4. Peguero-Lo Presti

6.1.4.5. Alterações de Repolarização Ventricular

6.1.5. Sobrecarga Ventricular Direita (SVD)

6.1.5.1. Eixo do QRS

6.1.5.2. Onda R Ampla

6.1.5.3. Morfologia qR ou qRs

6.1.5.4. Morfologia rsR’

6.1.5.5. Repolarização Ventricular

6.1.5.6. Critério de SEATTLE para SVD

6.1.6. Sobrecarga Biventricular

6.1.7. Diagnóstico Diferencial do Aumento de Amplitude do QRS

7. Análise dos Bloqueios (Retardo, Atraso de Condução)

Intraventriculares

7.1. Bloqueios Intraventriculares

7.1.1. Bloqueio do Ramo Esquerdo (BRE)

7.1.1.1. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo em Associação com Sobrecarga

Ventricular Esquerda

7.1.1.2. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo em Associação com Sobrecarga

Ventricular Direita (ao Menos 2 dos 3 Critérios)

7.1.2. Bloqueio do Ramo Direito (BRD)

7.1.2.1. Atraso Final de Condução

7.1.3. Bloqueios Divisionais do Ramo Esquerdo

7.1.3.1 Bloqueio Divisional Anterossuperior Esquerdo (BDAS)

7.1.3.2. Bloqueio Divisional Anteromedial Esquerdo (BDAM)

7.1.3.3. Bloqueio Divisional Posteroinferior Esquerdo (BDPI)

7.1.4. Bloqueios Divisionais do Ramo Direito

7.1.4.1. Bloqueio Divisional Superior Direito (BDSRD)

7.1.4.2. Bloqueio Divisional Inferior Direito (BDIRD)

7.1.5. Associação de Bloqueios

7.1.5.1. BRE Associado ao BDAS

7.1.5.2. BRE Associado ao BDPI

7.1.5.3. BRD Associado ao BDAS

7.1.5.4. BRD Associado ao BDPI

7.1.5.5. BRD Associado ao BDAS e BDAM

7.1.5.6. BDAS Associado ao BDAM

7.1.5.7. Bloqueio de Ramo Mascarado

7.1.6. Situações Especiais Envolvendo a Condução Intraventricular

7.1.6.1. Bloqueio Peri-infarto

7.1.6.2. Bloqueio Peri-isquemia

7.1.6.3. Fragmentação do QRS (fQRS)

7.1.6.4. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo Atípico

7.1.6.5. Bloqueio Intraventricular Parietal ou Purkinje/Músculo ou Focal

8. Análise do ECG nas Coronariopatias

8.1. Critérios Diagnósticos da Presença de Isquemia Miocárdica

8.1.1. Presença de Isquemia

8.1.2. Isquemia Circunferencial ou Global

8.1.3. Alterações Secundárias

8.2. Critérios Diagnósticos da Presença de Lesão

8.3. Definição das Áreas Eletricamente Inativas (AEI)

8.4. Análise Topográfica da Isquemia, Lesão e Necrose

8.4.1. Análise Topográfica das Manifestações Isquêmicas ao ECG (Meyers)

8.4.2. Análise topográfica das manifestações isquêmicas pelo ECG em

associação à ressonância magnética

8.4.3. Correlação Eletrocardiográfica com a Artéria Envolvida

8.5. Infartos de Localização Especial

8.5.1. Infarto do Miocárdio de Ventrículo Direito

8.5.2. Infarto Atrial

8.6. Diagnósticos Diferenciais

8.6.1. Isquemia Subepicárdica

8.6.2. Infarto Agudo do Miocárdio (IAM) com Supra de ST

8.7. Associação de Infarto com Bloqueios de Ramo

8.7.1. Infarto de Miocárdio na Presença de Bloqueio de

Ramo Direito (BRD)

8.7.2. Infarto do Miocárdio na Presença de Bloqueio de

Ramo Esquerdo (BRE)

9. Análise da Repolarização Ventricular

9.1. Repolarização Ventricular

9.1.1. Repolarização Ventricular Normal

9.1.1.1. Ponto J

9.1.1.2. Segmento ST

9.1.1.3. Onda T

9.1.1.4. Onda U

9.1.1.5. Intervalo QT (QT) e Intervalo QT Corrigido (QTc)

9.1.2. Variantes da Repolarização Ventricular Normal

9.1.2.1. Padrão de Repolarização Precoce (RP)

10. O ECG nas Canalopatias e Demais Alterações

Genéticas

10.1. A Genética e o ECG

10.1.1. Canalopatias

10.1.1.1. Síndrome do QT Longo Congênito

10.1.1.2. Síndrome do QT Curto

10.1.1.3. Síndrome de Brugada

10.1.1.4. Taquicardia Catecolaminérgica

10.1.2. Doenças Genéticas com Acometimento Primário Cardíaco

10.1.2.1. Cardiomiopatia (Displasia) Arritmogênica de

Ventrículo Direito

10.1.2.2. Cardiomiopatia Hipertrófica

10.1.3. Doenças Genéticas com Acometimento Secundário Cardíaco

10.1.3.1. Distrofia Muscular

11. Caracterização das Alterações Eletrocardiográficas

em Situações Clínicas Específicas

11.1. Condições Clínicas que Alteram o ECG

11.1.1. Ação Digitálica

11.1.2. Alterações de ST-T por Fármacos

11.1.3. Alternância Elétrica

11.1.4. Alternância da Onda T

11.1.5. Comprometimento Agudo do Sistema Nervoso Central

11.1.6. Comunicação Interatrial (CIA)

11.1.7. COVID-19

11.1.8. Derrame Pericárdico

11.1.9. Dextrocardia

11.1.10. Dextroposição

11.1.11. Distúrbios Eletrolíticos

11.1.11.1. Hiperpotassemia

11.1.11.2. Hipopotassemia

11.1.11.3. Hipocalcemia

11.1.11.4. Hipercalcemia

11.1.12. Doença Pulmonar Obstrutiva Crônica (DPOC)

11.1.13. Drogas Antiarrítmicas

11.1.13.1. Amiodarona

11.1.13.2. Propafenona

11.1.13.3. Sotalol

11.1.14. Efeito Dielétrico

11.1.15. Embolia Pulmonar

11.1.16. Fenômeno de Ashman (ou de Gounaux-Ashman)

11.1.17. Hipotermia

11.1.18. Hipotireoidismo

11.1.19. Insuficiência Renal Crônica

11.1.20. Pericardite

11.1.21. Quimioterápicos

12. O ECG em Atletas

12.1. A Importância do ECG do Atleta

12.1.1. Achados Eletrocardiográficos Normais (Grupo 1)

12.1.2. Achados Eletrocardiográficos Anormais (Grupo 2)

12.1.3. Achados Eletrocardiográficos Limítrofes (Grupo 3)

13. O ECG em Crianças

13.1. Introdução

13.2. Aspectos Técnicos

13.3.Parâmetros Eletrocardiográficos e suas Variações

13.3.1. Frequência Cardíaca e Ritmo Sinusal

13.3.1.1. Possíveis Alterações

13.3.1.1.1. Arritmia Sinusal

13.3.1.1.2. Taquicardia Sinusal

13.3.1.1.3. Bradicardia Sinusal

13.3.1.1.4. Outras Bradicardias

13.3.2. A onda P e a Atividade Elétrica Atrial

13.3.2.1. Possíveis Alterações

13.3.2.1.1. Sobrecargas Atriais

13.3.2.1.2. Ritmo Juncional

13.3.3. Intervalo PR e a Condução Atrioventricular

13.3.3.1. Possíveis Alterações

13.3.3.1.1. Bloqueios Atrioventriculares

13.3.3.1.2. Intervalo PR curto e Pré-excitação Ventricular

13.3.4. Atividade Elétrica Ventricular

13.3.4.1. Possíveis Alterações

13.3.4.1.1. Alterações do Eixo e da Amplitude do QRS

13.3.4.1.2. Alterações das Ondas Q

13.3.4.1.3. Distúrbios da Condução Intraventricular

13.3.4.1.4. Onda Épsilon e a Cardiomiopatia Arritmogênica do

Ventrículo Direito

13.3.5. Repolarização Ventricular

13.3.5.1. Intervalo QT

13.3.5.1.1. Possíveis Alterações

13.3.5.1.1.1. Síndrome do QT Longo

13.3.5.1.1.2. Síndrome do QT Curto

13.3.5.2. Segmento ST

13.3.5.2.1.1. Desnivelamentos do Segmento ST

13.3.5.2.1.2. Repolarização Precoce

13.3.5.2.1.3. Padrão eletrocardiográfico de Brugada

13.3.5.3. Onda T

13.3.5.4. Onda U

13.4. Distúrbios do Ritmo Cardíaco

13.5. Reconhecimento do Situs, da Posição Cardíaca e da

Inversão Ventricular

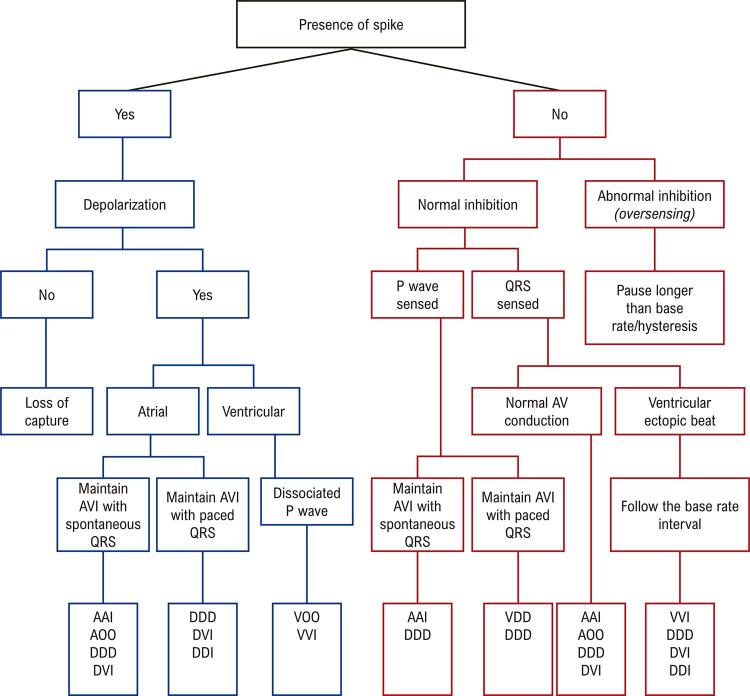

14. O ECG durante Estimulação Cardíaca Artificial

14.1. Estimulação Cardíaca Artificial (ECA)

14.1.1. Termos Básicos

14.1.2. Análise das Características Eletrocardiográficas dos DCEI

15. Tele-eletrocardiografia

Referências

Introdução

A revisão das diretrizes de eletrocardiografia deve-se ao fato do surgimento de avanços no entendimento de diversas doenças, com repercussões importantes no traçado eletrocardiográfico. Alguns podem imaginar que a interpretação do eletrocardiograma (ECG) não teve mudanças ao longo do tempo; certamente esquecem as doenças recentemente descritas e outras cujos mecanismos eletrofisiológicos foram melhor entendidos na atualidade. Alguns parâmetros eletrocardiográficos são considerados importantes marcadores prognósticos na doença de Chagas, além de ser possível identificar alterações consideradas como preditores de mortalidade na população geral (idade ao ECG - ECG-age). Uma questão crucial é: quando indicar a realização de um ECG?

O ECG é um exame simples, barato e não invasivo. Permite uma ideia da condição cardíaca do indivíduo e pode eventualmente identificar situações de risco de morte súbita. Assim, o achado de um ECG dentro dos limites da normalidade permite antecipar que a função ventricular deve estar normal ou próxima disto, fato importante no primeiro contato com o paciente.

Achamos que todas as pessoas deveriam ter um ECG em algum momento da vida, que somente fosse repetido segundo necessidade clínica. Algumas diretrizes colocam indicação IIb para a realização do ECG em indivíduos assintomáticos da população geral, e classe IIa na presença de hipertensão e ou diabetes. 1

A possibilidade de transmissão dos exames através da internet permitiu a difusão da tecnologia por diversas regiões carentes do nosso país e um melhor padrão de atendimento assistencial. Nos últimos anos, observou-se um aumento significativo de estudos (com milhões de ECG’s analisados) sobre inteligência artificial e sistemas de interpretação automática como ferramentas adicionais para a eletrocardiografia. Alguns resultados conseguiram demonstrar a capacidade destes novos sistemas em identificar determinadas arritmas, bem como predizer seu aparecimento, além de desfechos como acidente vascular encefálico (isquêmico).

Assim, esperamos que esta versão ajude o médico clínico e/ou cardiologista na emissão dos laudos eletrocardiográficos de maneira uniforme, permitindo fácil entendimento e padronização da linguagem.

1. Normatização para Análise e Emissão do Laudo Eletrocardiográfico

1.1. Normatização para Análise Eletrocardiográfica

Para a correta interpretação eletrocardiográfica, três características devem ser consideradas:

Idade: as características do ECG variam com a faixa etária e acontecem no recém-nascido (RN), lactente, crianças e adolescentes até cerca dos 16 anos de idade. Nos dois primeiros grupos essas alterações são mais rápidas (Seção 13). Também os idosos podem apresentar ondas T negativas em V1, de forma isolada e às vezes em V2. 2

Biotipo: Os indivíduos longilíneos tendem a ter o coração verticalizado e os eixos resultantes principalmente da onda P e do complexo QRS comumente orientados para a direita com rotação horária nas derivações do plano frontal. Já nos brevilíneos, com corações horizontalizados, esses desvios costumam ser para a esquerda (plano frontal).

Sexo: nos adultos do sexo feminino é comum observar ondas T negativas em precordiais direitas, inclusive com QTc maiores que os do sexo masculino e as crianças.

1.2. O Laudo Eletrocardiográfico 1 , 3 - 5

1.2.1. Laudo Descritivo

Análise do ritmo e quantificação da frequência cardíaca;

Análise da duração, amplitude e morfologia da onda P e duração do intervalo PR;

Determinação do eixo elétrico de P, QRS e T;

Análise da duração, amplitude e morfologia do QRS;

Análise da repolarização ventricular e descrição das alterações do ST-T, QT e U, quando presentes.

1.2.2. Laudo Conclusivo

Deve conter a síntese dos diagnósticos listados nesta diretriz. Abreviaturas em laudos, textos científicos, protocolos, etc., poderão ser utilizadas, entre parênteses, após a denominação, por extenso, do diagnóstico.

1.2.3. Laudo Automatizado

Com o desenvolvimento tecnológico, nos últimos anos, houve uma melhora importante na acurácia das medidas automáticas dos aparelhos disponíveis, tornando a interpretação automatizada uma ferramenta auxiliar importante no laudo médico. Ainda assim, é fundamental a conferência destas métricas automáticas por uma revisão médica, já que o laudo é um ato médico. A simples utilização das aferições automáticas (métricas e vetoriais), assim como os laudos provenientes desses sistemas, sem revisão, não são recomendadas.

1.2.4. Laudo Via Internet

Os sistemas de Tele-ECG, 6 - 8 enviam os ECGs realizados à distância para os Centros de Referência para laudo. A técnica de execução dos ECGs (Unidades executoras), bem como a interpretação e os laudos (Centros de Referência), deverão seguir as mais recentes diretrizes nacionais e internacionais. Eles são parte integrante da Telecardiologia, que também abarca outros exames da especialidade, que são executados, registrados e transmitidos de um ponto a outro para interpretação à distância, como por exemplo, monitoração de marca-passo, Holter, gravador de eventos, entre outros. Dentre os vários benefícios da telecardiologia temos:

Pré-atendimento ao paciente em seu local de origem;

Redução do tempo e custo dispendido pelo paciente;

Maior rapidez na triagem por especialistas;

Acesso a especialistas em acidentes e emergências;

Facilita gerenciamento dos recursos de saúde;

Na reabilitação, aumenta a segurança do paciente pós-cirúrgico;

Cooperação e integração de pesquisadores para compartilhamento de registros clínicos;

Acesso a programas educacionais de formação e qualificação.

Segundo vários autores, a telecardiologia foi identificada como uma atividade social e economicamente vantajosa para os prestadores de serviço, pagadores e pacientes. Reconhecidamente é uma ferramenta útil para os locais afastados dos grandes centros.

2. Avaliação da Qualidade Técnica do Traçado

2.1. Critérios de Avaliação Técnica dos Traçados

2.1.1. Calibração do Eletrocardiógrafo

Nos aparelhos analógicos a verificação da calibração se faz sempre necessária. O padrão normal deve ter 1 mV (10 mm). Nos aparelhos mais modernos (computadorizados com traçados digitalizados), a verificação do padrão do calibrador é realizada automaticamente. Os filtros devem seguir as normas internacionalmente aceitas, principalmente da AHA. Para os filtros de alta frequência de, no mínimo, 150 Hz para os grupos de adultos e adolescentes. Para crianças, até 250 Hz. Filtros com essas frequências mais baixas podem interferir na captação das espículas de marcapassos. Filtro de baixa frequência utiliza-se 0,05Hz. Alguns aparelhos usam filtros de fase bidirecional. 9

2.1.2. Troca de Eletrodos

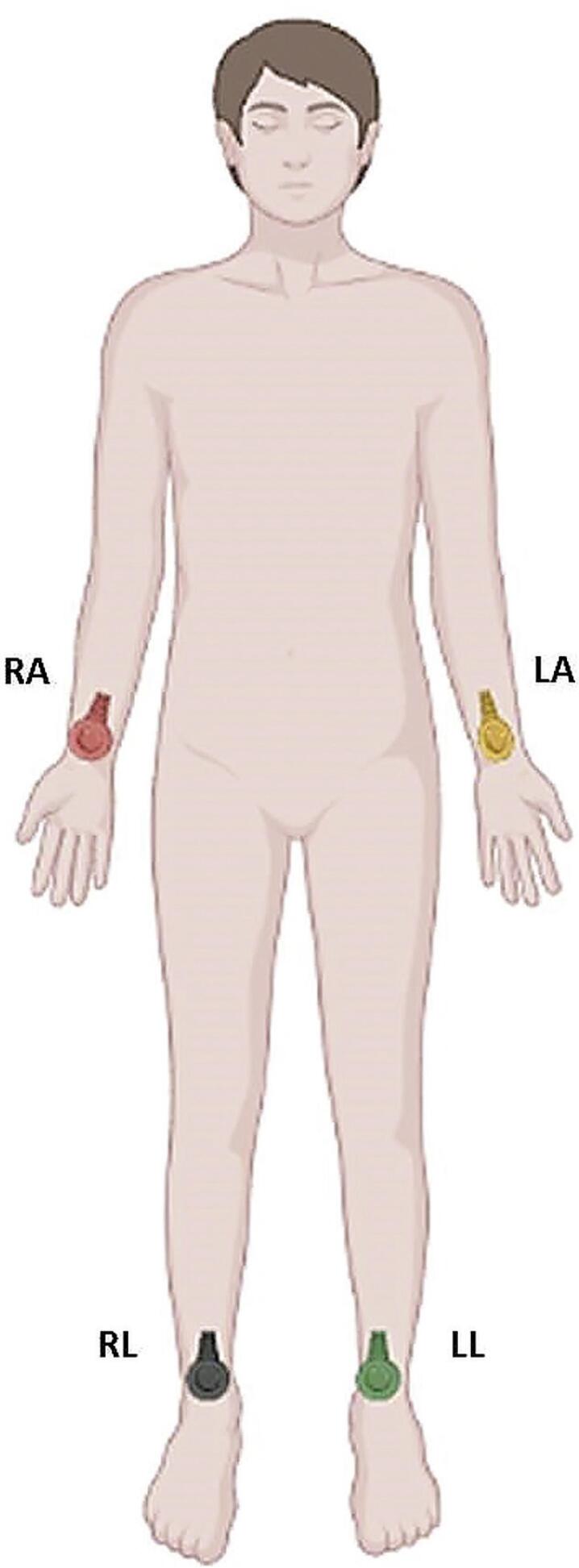

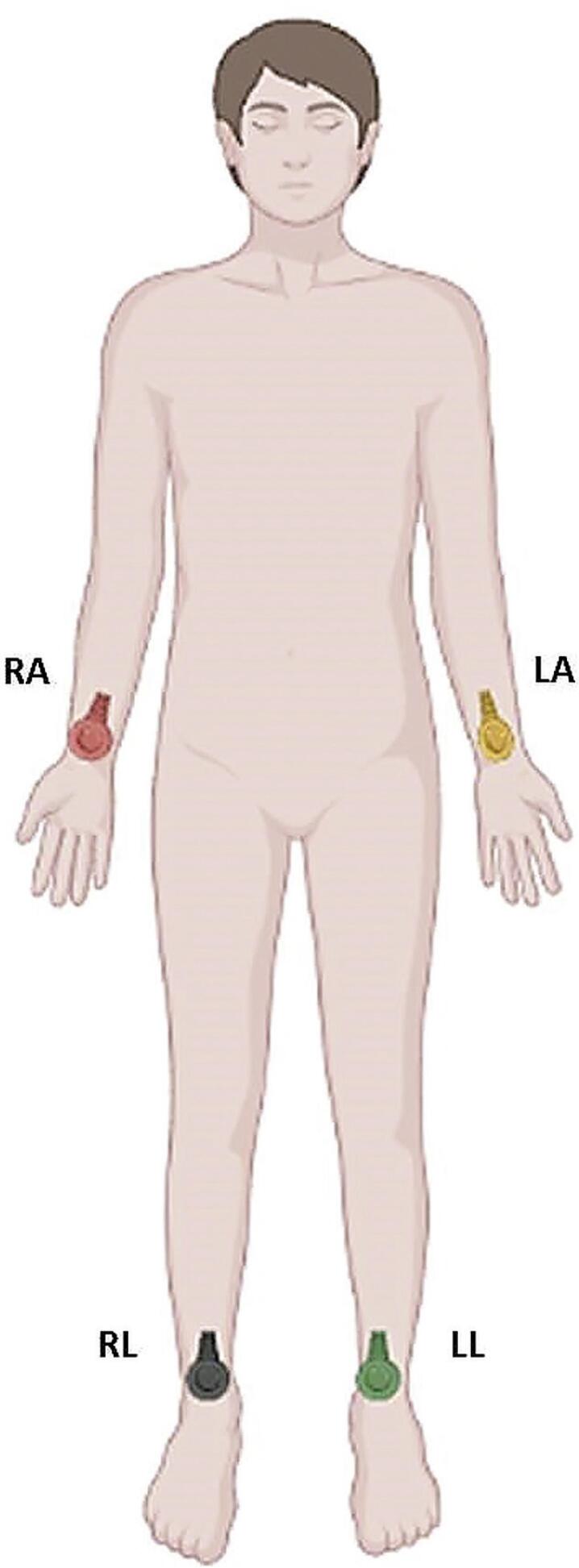

A Figura 2.1 mostra a posição correta dos eletrodos periféricos (braço direito (RA), braço esquerdo (LA), perna direita (RL) e perna esquerda (LL)) com suas respectivas cores vermelho, amarelo, preto e verde).

Figura 2.1. Localização dos eletrodos periféricos. RA: braço direito; LA: braço esquerdo;

RL: perna direita; LL: perna esquerda.

2.1.2.1. Posicionamento Trocado dos Eletrodos

2.1.2.1.1. Eletrodos dos MMSS Trocados entre Si

Apresentam derivações D1 com ondas negativas e aVR com ondas positivas.

2.1.2.2. Eletrodo dos MMII trocado por um eletrodo de um dos MMSS

Linha isoelétrica ou amplitude de ondas muito pequenas em D2 (braço direito) ou D3 (braço esquerdo). A troca dos eletrodos dos membros superiores com os dos inferiores mostra esse padrão em D1, pois produz uma diferença de potencial desprezível nos membros superiores.

2.1.2.3. Troca de Eletrodos entre Braço Esquerdo e Perna Esquerda

É a troca de mais difícil identificação. O SÂQRS tende a desviar-se para a esquerda. Pode parecer um ECG normal, mas produz as seguintes alterações:

onda P invertida em D3;

D1 e D2 trocam de posição. D1 tem voltagem de QRS mais ampla e menor em D2;

em D3 invertem-se P, QRS e T. Também são trocadas as posições de aVL com aVF. A derivação aVR não se altera.

2.1.2.4. Troca de Eletrodos Precordiais

Alteração da progressão normal da onda R de V1 a V6.

2.1.2.5. Eletrodos V1 e V2 Mal Posicionados

Eletrodos V1 e V2 posicionados incorretamente acima do segundo espaço intercostal podem produzir padrão rSr’ simulando atraso final de condução, ou morfologia rS de V1 a V3 e onda P negativa em V1, simulando SAE.

2.1.3. Outras Interferências

2.1.3.1. Tremores Musculares

Tremores musculares podem interferir na linha de base, mimetizando alterações eletrocardiográficas como flutter atrial e fibrilação ventricular 10 no paciente parkinsoniano.

2.1.3.2. Neuroestimulação

Portadores de afecções do SNC que necessitam do uso de dispositivos de estimulação elétrica artificial podem apresentar artefatos que mimetizam a espícula de marcapasso cardíaco.

2.1.3.3. Frio, Febre, Soluços, Agitação Psicomotora

São outras condições que produzem artefatos na linha de base e podem mimetizar arritmias como fibrilação atrial e flutter atrial.

2.1.3.4. “Grande Eletrodo” Precordial

A utilização de gel condutor em faixa contínua no precórdio, resultando num traçado igual de V1-V6, correspondente à média dos potenciais elétricos nestas derivações. 3

2.1.3.5. Oscilação da Linha de Base

Pode ser provocada por qualquer eletrodo mal fixado, movimentação dos membros, pela respiração ou em exames realizados com o paciente em cadeira de rodas. Nesse último caso outros artefatos também podem ser registrados.

2.1.3.6. Outras Interferências Elétricas e Eletromagnéticas

Esta resulta de interferências de linhas elétricas, equipamentos elétricos e telefonia celular. Para a realização do ECG deve-se solicitar ao paciente que retire todos os objetos metálicos e o telefone celular guardado na vestimenta. Os marca-passos transcutâneos podem produzir espícula, que pode ser confundida como falsa captura. O filtro utilizado também é de grande importância porque, às vezes, cria uma falsa falha de comando criando uma pausa representada por uma linha isoelétrica entre dois batimentos. 11 - 12

2.1.3.7. Alterações Decorrentes de Funcionamento Inadequado de Softwares e Sistemas de Aquisição de Sinais Eletrocardiográficos Computadorizados

A aquisição de dados por sistemas computadorizados, em alguns aparelhos eletrocardiográficos mais antigos, pode apresentar, raramente, problemas específicos e ainda não totalmente conhecidos. Como exemplo, na ausência de sinal eletrocardiográfico em um dos eletrodos, o sistema pode contrabalançar os outros sinais adquiridos e criar complexos QRS bizarros. Aparelhos eletrocardiográficos de 12 derivações simultâneas que possuem aferições automáticas de durações das ondas P e QRS podem apresentar medidas superestimadas das mesmas. Isso ocorre pois o software utiliza a onda mais precoce e a mais tardia dentre as 12 derivações para gerar tal medida.

3. A Análise do Ritmo Cardíaco

3.1. Análise da Onda P, Frequência Cardíaca e Ritmo

Estudos populacionais sobre valores de normalidade dos parâmetros eletrocardiográficos são utilizados há muitos anos como referência para nossa população, mesmo sabendo que diferenças étnicas têm influência sobre o que é considerado normal. Em 2017, dentre as diversas informações obtidas pelo estudo ELSA-Brasil, foi publicado estudo sobre valores da normalidade para a população brasileira sem doença cardíaca. 13

Os parâmetros que serão abordados no item 3 referem-se ao ECG de adulto. O ECG pediátrico será abordado no item 13.

3.1.1. Definição do Ritmo Sinusal (RS)

Ritmo fisiológico do coração, que se origina no átrio direito alto, observado no ECG de superfície pela presença de ondas P positivas nas derivações D1, D2 e aVF, independentemente da presença ou não do complexo QRS. O eixo de P pode variar entre 0° e +90°. A onda P normal possui amplitude máxima de 2,5 mm e duração igual ou inferior a 110 ms. Podem ocorrer modificações de sua morfologia dependentes da frequência cardíaca, bem como da sua orientação (SÂP) nas derivações observadas. 14

3.1.2. Frequência da Onda P Sinusal

A faixa de normalidade da frequência cardíaca em vigília é entre 50 bpm e 99 bpm. 14 - 16

3.2. Análise das Alterações de Ritmo Supraventricular

3.2.1. Definição de Arritmia Cardíaca

Alteração da formação e/ou condução do impulso elétrico através do miocárdio. 17 Após a definição (ou não) da presença do ritmo sinusal, busca-se a presença de arritmia cardíaca.

3.2.2. Arritmia Supraventricular

Ritmo que se origina acima do feixe de His. A identificação do local de origem da arritmia será usada sempre que possível. Quando não, será empregado o termo genérico supraventricular.

3.2.3. Presença de Onda P Sinusal

3.2.3.1. Arritmia Sinusal (AS)

Geralmente fisiológica, depende do sistema nervoso autônomo, e caracteriza-se pela variação dos intervalos PP entre 160 ms e 220 ms, durante o ritmo sinusal. A variação fásica é a relacionada com a respiração (comum na criança) e a não fásica não possui essa relação.

3.2.3.2. Bradicardia Sinusal (BS)

Refere-se ao ritmo sinusal com frequência inferior a 50 bpm.

3.2.3.3. Bloqueio Sinoatrial de Segundo Grau

O bloqueio de saída de segundo grau da despolarização sinusal faz com que ocorra a ausência de inscrição da onda P em um ciclo. O bloqueio sinoatrial do tipo I (BSAI) se caracteriza por ciclos PP progressivamente mais curtos até que ocorra o bloqueio. O bloqueio sinoatrial tipo II (BSA II) não apresenta diferença entre os ciclos PP e a pausa corresponde a 2 ciclos PP prévios. Os bloqueios sinoatriais de primeiro grau não são visíveis ao ECG convencional. Os bloqueios de terceiro grau serão observados na forma de ritmo de escape atrial ou juncional.

3.2.3.4. Bloqueios Interatriais (BIA)

Retardo da condução entre o átrio direito e o esquerdo, que pode ser classificado em primeiro grau (duração da onda P maior ou igual a 120 ms), segundo grau (padrão transitório) e terceiro grau ou avançado (onda P com duração maior ou igual a 120 ms, bifásica ou “plus-minus” em parede inferior, relacionado a arritmias supraventriculares e síndrome de Bayés). 18 , 19

3.2.3.5. Taquicardia Sinusal (TS)

Refere-se ao ritmo sinusal com frequência superior (ou igual) a 100 bpm.

3.2.4. Ausência de Onda P Antes do QRS

3.2.4.1. Fibrilação Atrial (FA)

A atividade elétrica atrial desorganizada, com frequência atrial entre 450 e 700 ciclos por minuto e resposta ventricular variável. A linha de base pode se apresentar isoelétrica, com irregularidades finas, grosseiras ou por um misto destas alterações (ondas “ f ”). A ocorrência de intervalos RR regulares indica a existência de dissociação atrioventricular. Para a denominação da resposta ventricular, num ECG com FA, deve-se calcular a FC (bpm) a partir de um traçado de 6 s (número de QRS neste período multiplicado por 10). Assim, teremos as seguintes possibilidades de resposta ventricular:

Ritmo de FA com baixa resposta ventricular, quando a FC estiver menor ou igual a 50 bpm;

Ritmo de FA com controle adequado da FC (em repouso), quando a resposta ventricular estiver entre 60 e 80 bpm;

Ritmo de FA com controle leniente (ou inadequado) da FC (em repouso), quando a resposta ventricular estiver entre 90 e 110 bpm;

Ritmo de FA com resposta ventricular elevada, quando a FC estiver maior a 110 bpm.

3.2.4.2. Flutter Atrial

Atividade elétrica atrial organizada (macrorreentrante) que utiliza extensa região do átrio direito, sendo uma delas o istmo cavotricuspídeo (ICT). O ICT pode ser utilizado tanto no sentido anti-horário (90% dos casos) como no sentido horário (10%). Em ambas as situações, denomina-se flutter atrial comum (por utilizar o ICT). Quando no sentido horário, é chamado de comum reverso. No flutter atrial comum, as conhecidas ondas “F” apresentam frequência entre 240 e 340 bpm, bem como um padrão característico das mesmas: aspecto em dentes de serrote, negativas nas derivações inferiores e, geralmente, positivas em V1. Graus variados da condução AV podem ocorrer, sendo que quando superiores a 2:1 facilitam a observação das ondas “F”. Já no flutter atrial reverso, as ondas “F” possuem frequências mais elevadas entre 340 e 430 bpm. As ondas “F” são, além de positivas nas derivações inferiores, mais alargadas. Ao ECG, não é possível a diferenciação entre o flutter atrial comum reverso e uma taquicardia atrial esquerda (com origem na veia pulmonar superior direita). O chamado Flutter atrial incomum é aquele que não utiliza o ICT, portanto, está incluída nessa classificação a taquicardia atrial cicatricial, a taquicardia da veia cava inferior e a taquicardia por reentrada no anel mitral (todas são muito difíceis de serem diagnosticadas pelo ECG (recebem o nome genérico de taquicardia atrial).

3.2.4.3. Ritmo Juncional

Trata-se de ritmo de suplência ou de substituição originado na junção AV, com QRS iguais ou ligeiramente diferentes aos de origem sinusal. Trata-se de aberrância pela origem diferente do estímulo e não aberrância fásica, que depende do estímulo ser alterado pela fase 3 (precoce) ou 4 (tardio) do potencial de ação. Pode apresentar-se sem onda P visível ao ECG. Estas “posições” da onda P devem-se às velocidades de condução do estímulo elétrico aos átrios e aos ventrículos. Ao chegar antes aos ventrículos, e depois aos átrios, a onda P fica localizada dentro ou após o complexo QRS. Quando a frequência for inferior a 50 bpm é designado ritmo juncional de escape. Quando a frequência for superior a 50 bpm é chamado de ritmo juncional ativo e, se acima de 100 bpm, é chamado de taquicardia juncional.

3.2.4.4. Extrassístole Juncional

Batimento ectópico precoce originado na junção AV. São três as possíveis apresentações eletrocardiográficas:

Onda P negativa nas derivações inferiores com intervalo PR curto;

Ausência de atividade atrial pregressa ao QRS (onda P dentro do QRS);

Onda P negativa nas derivações inferiores após o complexo QRS.

O complexo QRS apresenta-se de morfologia e duração similar ao do ritmo basal, embora aberrâncias de condução possam ocorrer (ver itens 3.2.8.1 e 3.2.8.2).

3.2.4.5. Taquicardia por Reentrada Nodal Comum (TRN) 20

Esta taquicardia utiliza a estrutura do nó atrioventricular; e tem como mecanismo eletrofisiológico a reentrada nodal. Um circuito utiliza a via rápida, no sentido ascendente, e o outro utiliza a via lenta, no sentido descendente. Se o QRS basal for normal estreito, durante a taquicardia poderemos notar pseudo-ondas “s” em parede inferior e morfologia rSr’ (pseudo r’) em V1, que refletem a ativação atrial no sentido nó AV / nó sinusal. Essa ativação retrógrada atrial, em sua maioria, ocorre em até 80 ms após o início do QRS (RP<80ms). Muitas vezes a onda de ativação atrial está dentro do QRS e, dessa forma, não é observada no ECG. A TRN comum é muito semelhante, ao ECG, com a TAV ortodrômica que será detalhada a seguir. Utiliza-se o intervalo RP para se fazer essa distinção entre elas. Nos casos de TRN com QRS alargado, faz-se necessário o diagnóstico diferencial com taquicardias de origem ventricular.

3.2.4.6. Taquicardia por Reentrada Atrioventricular Ortodrômica (TRAV)

Esta taquicardia por reentrada utiliza o sistema de condução normal no sentido anterógrado e uma via anômala no sentido retrógrado. O QRS da taquicardia geralmente é estreito e a onda P retrógrada, geralmente localizada no segmento ST, pode apresentar-se com morfologia diversa, dependendo da localização da via acessória. O intervalo RP é superior a 80 ms.

3.2.5. Presença da Onda P Não Sinusal Antes do QRS

3.2.5.1. Ritmo Atrial Ectópico (RAE)

O ritmo atrial ectópico corresponde a uma atividade atrial em localização diversa da região anatômica do nó sinusal. Desta forma, a onda P apresenta-se com morfologia (polaridade) diferente daquela que caracteriza o ritmo sinusal.

3.2.5.2. Ritmo Atrial Multifocal (RAM)

Ritmo originado em focos atriais múltiplos, com frequência cardíaca inferior a 60 bpm, reconhecido eletrocardiograficamente pela presença de, pelo menos, 3 morfologias de ondas P e 3 diferentes intervalos PR. Os intervalos PP e PR, frequentemente, são variáveis, habitualmente observa-se uma P para um QRS, podendo ocorrer ondas P bloqueadas.

3.2.5.3. Ritmo Juncional

Mencionado no item 3.2.4.3, caracteriza-se pelas ondas P negativas nas derivações DII, DIII e aVF, além do intervalo PR curto. Quando a frequência for inferior a 50 bpm é designado ritmo juncional de escape. Quando a frequência for superior a 50 bpm é chamado de ritmo juncional ativo e, se acima de 100 bpm, é chamado de taquicardia juncional.

3.2.5.4. Batimento de Escape Atrial

Durante uma interrupção temporária do automatismo sinusal normal, é possível observar um batimento “de suplência”, de origem atrial, consequente a esta inibição do nó sinusal. Caracteriza-se por ser um batimento tardio, de origem atrial, portanto com onda P de morfologia diferente da sinusal.

3.2.5.5. Extrassístole Atrial (EA)

Batimento ectópico atrial precoce. Pode reciclar o ciclo PP basal. Usa-se a sigla ESV para extrassístole supraventricular.

3.2.5.6. Extrassístole Atrial Bloqueada ou Não Conduzida

Batimento ectópico de origem atrial que não consegue ser conduzido ao ventrículo, não gerando, portanto, complexo QRS. A não condução pode ser devida à precocidade acentuada da EA, que encontra o sistema de condução intraventricular em período refratário, ou devido a doença do sistema de condução His-Purkinje. Estas EA bigeminadas, não conduzidas, podem gerar bradicardia.

3.2.5.7. Taquicardia Atrial (TA)

Ritmo atrial originado em região diversa do nó sinusal, caracterizado pela presença de onda P distinta da sinusal com frequência atrial superior a 100 bpm. É comum a ocorrência de condução AV variável.

3.2.5.8. Taquicardia Atrial Multifocal (TAMF)

Apresenta as mesmas características do ritmo atrial multifocal, com frequência atrial superior a 100 bpm.

3.2.5.9. Taquicardia por Reentrada Nodal Incomum

O local de origem e o circuito são similares à TRN comum (3.2.4.5), mas o sentido de ativação atrial e ventricular, pelas vias lenta e rápida, é inverso, motivo pelo qual a ativação atrial retrógrada se faz temporalmente mais tarde, com o característico intervalo RP maior que o PR. Desta forma, a TRN incomum não é um diagnóstico diferencial com a TRN comum, nem com a TAV ortodrômica.

3.2.5.10. Taquicardia de Coumel

Taquicardia supraventricular mediada por uma via anômala com condução retrógrada exclusiva e decremental. Caracteriza-se por uma taquicardia com intervalo RP longo e é diagnóstico diferencial com as descritas nos itens 3.2.5.7 e 3.2.5.9.

3.2.6. Pausas

Define-se pausa pela ausência de onda P e complexo QRS em um intervalo superior a 1,5 s e passa a apresentar importância clínica quando maior que 2,0 s. A ocorrência de pausas no traçado pode relacionar-se à presença de parada sinusal, extrassístole atrial não conduzida, bloqueio sinoatrial e bloqueio atrioventricular.

3.2.6.1. Parada Sinusal (PS)

Corresponde a uma pausa na atividade sinusal superior a 1,5 vezes o ciclo PP básico.

3.2.6.2. Disfunção do Nó Sinusal (DNS)

A incapacidade do nódulo sinusal em manter uma frequência cardíaca superior às necessidades fisiológicas para a situação do momento denomina-se disfunção do nó sinusal. Ao ECG, essa anormalidade (ou disfunção) do nó sinusal é entidade que engloba a pausa sinusal, o bloqueio sinoatrial, a bradicardia sinusal, ritmos de substituição, a fibrilação atrial, o flutter atrial, a síndrome bradi-taqui, etc. 21

3.2.7. Classificação de Taquicardias Supraventriculares Baseadas no Intervalo RP

Intervalo RP é uma medida comumente realizada para caracterizar uma taquicardia supraventricular. A mensuração é feita a partir do complexo QRS até a onda P seguinte (RP). A depender da posição desta onda P, podemos ter um RP curto (onda P encontra-se antes da metade de dois QRS) ou um RP longo (onda P encontra-se após a metade de dois QRS). Assim, as taquicardias paroxísticas supraventriculares podem ser divididas em:

Taquicardia com RP’ curto (habitualmente até 120-140ms), como observado na taquicardia por reentrada nodal comum e na taquicardia por reentrada via feixe anômalo;

Taquicardia com RP’ longo, como observado na taquicardia atrial, na taquicardia por reentrada nodal incomum e na taquicardia de Coumel (reentrada por feixe anômalo de condução retrógrada exclusiva e decremental). 22

3.2.8. Arritmias Supraventriculares com Complexo QRS Alargado

3.2.8.1. Aberrância de Condução

Um estímulo supraventricular que encontra dificuldade de propagação regional no sistema de condução, gerando um QRS com morfologia diferente, em comparação ao complexo QRS de base, o qual pode apresentar padrão de bloqueio de ramo, de bloqueio divisional ou associação de ambos.

3.2.8.2. Extrassístole Atrial com Aberrância de Condução

Batimento atrial reconhecido eletrocardiograficamente por apresentar onda P precoce seguida de QRS com morfologia de bloqueio de ramo, bloqueio divisional ou associação de ambos.

3.2.8.3. Taquicardia Supraventricular com Aberrância de Condução

Denominação genérica para as taquicardias supracitadas que se expressem com condução aberrante.

3.2.8.4. Taquicardia por Reentrada Atrioventricular Antidrômica

A taquicardia por reentrada utiliza uma via acessória no sentido anterógrado e o sistema de condução no sentido retrógrado. O QRS é aberrante e caracteriza-se pela presença de pré-excitação ventricular. O diagnóstico diferencial deve ser feito com taquicardia ventricular. A observação da despolarização atrial retrógrada 1:1 é importante para o diagnóstico da via anômala, e a dissociação AV para o de taquicardia ventricular.

4. Condução Atrioventricular

4.1. Definição da Relação Atrioventricular (AV) Normal

O período do início da onda P ao início do QRS determina o intervalo PR, tempo em que ocorre a ativação atrial e o retardo fisiológico na junção atrioventricular (AV) e/ou sistema His-Purkinje, cuja duração é de 120 a 200 ms, considerando FC de até 90 bpm. O intervalo PR varia de acordo com a FC e a idade, existindo quadros de correção.

4.1.1. Atraso da Condução Atrioventricular (AV) 23 - 26

Ao estudarmos os atrasos, é importante lembrar da característica eletrofisiológica normal do nódulo AV, denominada condução decremental. Essa propriedade refere-se à redução da velocidade de condução do estímulo elétrico no nó AV e pode ser estimada por meio do intervalo PR no ECG convencional. Esse intervalo é considerado normal no adulto quando se encontra entre 120 a 200 ms e depende muito da idade e da frequência cardíaca.

Os atrasos da condução atrioventricular (AV) ocorrem quando os impulsos atriais sofrem retardo ou falham em atingir os ventrículos.

Anatomicamente, esses atrasos podem estar localizados no próprio nódulo AV (bloqueio nodal), no tronco His–Purkinje (bloqueio intra-His) ou abaixo dele (bloqueio infra-His). Geralmente os atrasos nodais apresentam-se com complexos QRS estreitos (< 120 ms) e possuem bom prognóstico, e podem ser expressos pelo aumento do intervalo PR. Por outro lado, é comum que os atrasos intra e infra-His cursem com complexos QRS alargados e pior evolução. Não é comum, nesses casos, a presença de intervalo PR normal.

Salientamos que o nó AV sofre importante influência do sistema nervoso autônomo, portanto, nas situações em que haja predominância do tônus parassimpático (durante sono, atletas), pode-se observar bloqueio AV de 1º grau e/ou bloqueio AV de 2º grau tipo I, sem haver lesão do nó AV.

4.1.1.1. Bloqueio AV de Primeiro Grau

Nesta situação, o intervalo PR é superior a 200 ms em adultos, para FC entre 50 a 90 bpm.

4.1.1.2. Bloqueio AV de Segundo Grau Tipo I (Mobitz I)

Nesta situação, o alentecimento da condução AV é gradativo (fenômeno de Wenckebach). Tipicamente, existe aumento progressivo do intervalo PR, sendo tais acréscimos gradativamente menores, até que a condução AV fique bloqueada e um batimento sinusal não consiga ser conduzido. Há, portanto, um gradual aumento do intervalo PR com concomitante encurtamento dos intervalos RR até uma onda P ser bloqueada. Pode ocorrer repetição desse ciclo por períodos variáveis, quando é possível notar que o intervalo PR após o batimento bloqueado será o menor dentre todos, e o que o sucede terá o maior incremento percentual em relação aos posteriores. A frequência de bloqueio pode ser variável, por exemplo, 5:4, 4:3, 3:2.

4.1.1.3. Bloqueio AV de Segundo Grau Tipo II (Mobitz II)

Nesta situação, existe uma interrupção súbita da condução AV. Nota-se condução AV 1:1 com intervalo PR fixo e, repentinamente, uma onda P bloqueada, seguida por nova condução AV 1:1 com PR semelhante aos anteriores. A localização desse bloqueio localiza-se na região intra/infra His-Purkinje.

4.1.1.4. Bloqueio AV 2:1

Caracteriza-se pela alternância de uma onda P conduzida e outra bloqueada de origem sinusal. A maior parte desse bloqueio localiza-se na região intra/infra His-Purkinje. Deve-se excluir o diagnóstico de extrassístoles atriais não conduzidas.

4.1.1.5. Bloqueio AV Avançado ou de Alto Grau

Nesta situação, existe condução AV em menos de 50% dos batimentos sinusais, sendo em proporção 3:1, 4:1 ou maior. Geralmente, a presença de condução AV é notada pelo intervalo PR constante em cada batimento seguido de um QRS. A maior parte desse bloqueio localiza-se na região intra/infra His-Purkinje. Podem acontecer escapes juncionais.

4.1.1.6. Bloqueio AV do Terceiro Grau ou BAV Total (BAVT)

Neste caso, os estímulos de origem sinusal não conseguem chegar aos ventrículos e despolarizá-los, fazendo com que um foco abaixo da região de bloqueio assuma o comando ventricular. Não existe, assim, correlação entre a atividade elétrica atrial e ventricular (dissociação atrioventricular), o que se traduz no ECG por ondas P não relacionadas ao QRS. A frequência do ritmo sinusal é maior que a do ritmo de escape. O bloqueio AV do terceiro grau pode ser intermitente ou permanente. Bloqueios com origem supra-hissiana podem apresentar-se com escapes de morfologia semelhantes ao do ECG basal, enquanto que a origem infra-hissiana evidencia complexos QRS largos como escapes.

4.1.1.7. Bloqueio AV Paroxístico

É a ocorrência, de forma súbita e inesperada, de uma sucessão de ondas P bloqueadas.

4.1.2. Pré-Excitação Ventricular 27 - 30

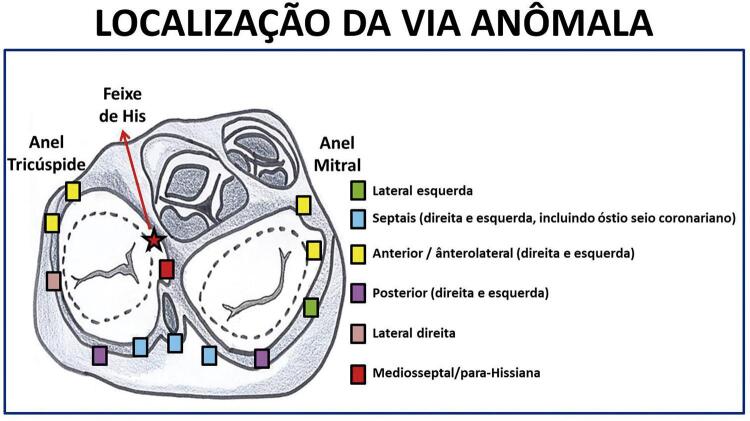

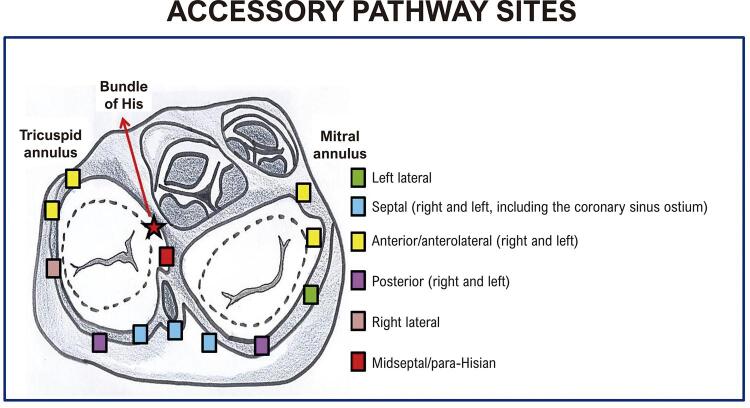

Em pacientes com pré-excitação, feixes musculares persistem, de permeio ao tecido fibroso, servindo como vias acessórias da condução do estímulo elétrico entre os átrios e os ventrículos. Essas vias extras podem estar em qualquer parte do anel atrioventricular ( Figura 4.1 ). São características do padrão clássico: intervalo PR menor que 120 ms durante o ritmo sinusal em adultos e menor que 90 ms em crianças (variando com a idade e a frequência cardíaca); entalhe da porção inicial do complexo QRS (onda delta), que interrompe a onda P ou surge imediatamente após seu término; duração do QRS maior que 120 ms em adultos e maior que 90 ms em crianças; alterações secundárias de ST e T. Na presença desses achados eletrocardiográficos, a presença de taquicardia paroxística supraventricular sintomática configura a Síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW). A via acessória pode ser localizada anatomicamente pelo ECG. As vias laterais esquerdas são as mais comuns (50% dos casos), seguidas das posterosseptais (25%), laterais direitas (15%) e anterosseptais (10%). As regiões anteriores do anel atrioventricular são superiores, assim, vias acessórias nessa localização determinam ativação no sentido supero-inferior, com positividade da onda delta nas derivações inferiores. Já a região basal posterior é inferior, dessa maneira vias acessórias aí situadas geram ativação anômala que foge dessa região, com consequente negatividade da onda delta nas derivações inferiores. Mais raramente, deve-se fazer o diagnóstico diferencial com a situação de PR curto sem onda delta, presente na síndrome de Lown-Ganong-Levine, 31 e o PR normal com pré-excitação ventricular, presentes nas vias fascículo ventriculares, como na variante de Mahaim. 32

Figura 4.1. Possíveis localizações das vias anômalas nos anéis tricúspide e mitral.

As vias anômalas podem ser categorizadas quando o complexo QRS é predominantemente positivo (R) em V1 e V2, o que indica uma via acessória à esquerda, e quando o QRS é negativo (QS ou rS), a via encontra-se à direita. As vias laterais esquerdas manifestam-se no ECG através de onda delta negativa nas derivações D1 e/ou aVL, positiva nas derivações D2, D3 e aVF, e em V1 e V2. As vias anômalas direitas apresentam onda delta positiva nas derivações D1, D2 e aVL e, geralmente, negativa nas derivações D3 e aVF, assim como em V1. O eixo elétrico do QRS no plano frontal é desviado para a esquerda. Já as vias posterosseptais apresentam ao ECG onda delta negativa em D2, D3 e aVF. A importância do reconhecimento das localizações das vias anterosseptais e mediosseptais está relacionada à sua proximidade ao feixe de His, trazendo maior risco durante a ablação com cateter. Em ambas as localizações, a onda delta é positiva nas derivações D1, D2 e aVL, além de negativa em D3 e aVR e positiva/isoelétrica em aVF, com eixo elétrico do QRS normal. Em 80%, a transição R/S ocorre em V2. 32

A análise dos complexos QRS em V1 e V2 fará a diferenciação se estão à direita ou à esquerda. 33

Existem vários algoritmos para a localização da via acessória, baseados na polaridade do QRS ou da via anômala. 34 - 36

Devemos lembrar que entidades podem simular a presença de pré-excitação (falsos WPW) como a cardiomiopatia hipertrófica e formas familiares de depósito septal de glicogênio (doença de Fabry).

4.1.3. Outros Mecanismos de Alteração da Relação AV Normal

4.1.3.1. Dissociação AV

A dissociação AV tem como causas os seguintes mecanismos: substituição, interferência, bloqueio atrioventricular e dissociação por arritmia. 37 Ocorrem dois ritmos dissociados, sendo um atrial, geralmente sinusal, com PP regular, e outro de origem juncional ou ventricular, também com RR regular. A frequência destes focos pode ser similar (dissociação isorritmica). O ritmo ventricular pode ser hiperautomático.

4.1.3.2. Ativação Atrial Retrógrada

A ativação do átrio origina-se a partir de um estímulo juncional ou ventricular, com condução retrógrada, geralmente pelo nó AV ou por uma via anômala. Observa-se QRS seguido de onda P negativa nas derivações inferiores.

5. Análise da Ativação Ventricular

5.1. Ativação Ventricular Normal

5.1.1. Definição do QRS Normal

O complexo QRS é dito normal quando a duração for inferior a 120 ms em todas as derivações e amplitude entre 5 e 20 mm nas derivações do plano frontal e entre 10 e 30 mm nas derivações precordiais, com orientação normal do eixo elétrico. 38 , 39

5.1.2. Eixo Elétrico Normal no Plano Frontal

Os limites normais do eixo elétrico do QRS no plano frontal situam-se habitualmente entre -30° e +90°.

5.1.3. Ativação Ventricular Normal no Plano Horizontal

Tem como característica a transição da morfologia rS, característica de V1, para o padrão qR típico do V6, onde observa-se um progressivo aumento da amplitude da onda r e, concomitantemente, uma gradual redução da onda de V2 até V6. Os padrões intermediários de RS (zona de transição) habitualmente ocorrem em V3 e V4. 16

5.1.4. Análise das Alterações de Ritmo Ventricular

5.1.4.1. Definição de Arritmia Cardíaca

Arritmia cardíaca pode ser definida como uma alteração da frequência, formação e/ou condução do impulso elétrico através do miocárdio. 17

5.1.4.2. Arritmia Ventricular

Arritmia ventricular é uma arritmia de origem abaixo da bifurcação do feixe de His, habitualmente expressa por QRS alargado.

5.1.4.3. Análise das Arritmias Ventriculares

5.1.4.3.1. Extrassístole Ventricular (EV) 40

Apresenta-se como batimento originado precocemente no ventrículo, geralmente com pausa pós extrassistólica, quando recicla o intervalo RR. Na ausência de pausa, é chamada de extrassístole ventricular interpolada. As EV geralmente apresentam duração do QRS superior a 120ms. Excepcionalmente (EVs com origem no septo ventricular ou próximas do sistema de condução) podem apresentar-se com duração inferior a 120ms. Em relação à forma, podem ser classificadas em monormórficas (quando apresentam a mesma morfologia) ou polimórficas (apresentam mais de uma morfologia) e de acordo com sua inter-relação podem ser denominadas de isoladas, pareadas, em salvas, bigeminadas, trigeminadas, quadrigeminadas ou ocultas.

5.1.4.3.2. Batimento(s) de Escape Ventricular(es)

Batimento(s) de origem ventricular, tardio(s) por ser(em) de suplência. Surge(m) em consequência da inibição temporária de ritmos anatomicamente mais altos.

5.1.4.3.3. Ritmo de Escape Ventricular – Ritmo Idioventricular

Trata-se de ritmo com origem nos ventrículos, com FC inferior a 40 bpm, ocorrendo em substituição a ritmos anatomicamente mais altos que foram inibidos ou bloqueados.

5.1.4.3.4. Ritmo Idioventricular Acelerado (RIVA)

Este ritmo origina-se no ventrículo (QRS alargado), tendo FC superior a 40 bpm (entre 50 e 130 bpm, mais usualmente entre 70 e 85 bpm), em consequência de automatismo aumentado. Não é ritmo de suplência, competindo com o ritmo basal do coração. Costuma ser autolimitado e está relacionado à doença isquêmica miocárdica (reperfusão/isquemia). 41

5.1.4.3.5. Taquicardia Ventricular (TV)

A taquicardia ventricular (TV) é um ritmo ventricular que se apresenta com três ou mais batimentos sucessivos com frequência cardíaca acima de 100 bpm.

5.1.4.3.5.1. Taquicardia Ventricular Monomórfica

Caracteriza-se por uma TV com morfologia uniforme na mesma derivação.

5.1.4.3.5.2. Taquicardia Ventricular Polimórfica (TVP)

Ritmo de origem ventricular, rápido, com QRS de três ou mais morfologias. Apresenta 2 padrões característicos: Torsade des Pointes (TdP) e a chamada taquicardia ventricular polimórfica verdadeira. 42

5.1.4.3.5.3. Taquicardia Ventricular Tipo Torsade des Pointes (TdP)

Trata-se de taquicardia com QRS largo, polimórfica, geralmente autolimitada, com QRS “girando” em torno da linha de base (torção das pontas). Normalmente, é precedida por ciclos longo-curto (extrassístole - batimento sinusal – extrassístole) e observa-se, durante o ritmo sinusal, intervalo QT longo, o qual pode ser congênito ou secundário a fármacos, distúrbios eletrolíticos ou determinadas doenças cardíacas. 43

5.1.4.3.5.4. Taquicardia Ventricular Bidirecional 44

Trata-se de taquicardia de origem ventricular que, ao conduzir-se para o ventrículo, apresenta-se com o ramo direito bloqueado constantemente (raramente BRE) e as divisões anterossuperior e posteroinferior do ramo esquerdo bloqueadas alternadamente, batimento a batimento. No plano frontal do ECG alternam-se um batimento com QRS positivo, seguido de outro com QRS negativo, sucessivamente (gerando o aspecto bidirecional). Esta arritmia está relacionada a quadros de intoxicação digitálica, doença miocárdica grave por cardiomiopatia avançada e casos sem cardiopatia estrutural, como a taquicardia catecolaminérgica familiar, sendo prenúncio de taquicardia ventricular polimórfica nestes indivíduos.

5.1.4.3.5.5. Quanto à Duração

Classificação de acordo com sua duração em segundos: taquicardia sustentada (TVS) ou não sustentada (TVNS), se o período da arritmia for ou não superior a 30 s e/ou sem sintomas de instabilidade hemodinâmica.

5.1.4.3.6. Batimento de Fusão

Corresponde a batimento originado nos ventrículos que se funde com o batimento supraventricular. Ao ECG, apresenta onda P seguida de QRS alargado, que é a soma elétrica do batimento supraventricular com a extrassístole ventricular (morfologia híbrida entre o batimento supraventricular e o de origem ventricular). Os batimentos de fusão são encontrados nas seguintes situações: pré-excitação ventricular, taquicardia ventricular, parassistolia e extrassistolia ventricular.

5.1.4.3.7. Batimento com Captura Supraventricular Durante Ritmo Idioventricular

Trata-se de batimento originado no átrio que consegue ultrapassar o bloqueio de condução (anatômico ou funcional) existente na junção AV e despolarizar o ventrículo totalmente ou parcialmente, gerando no último caso um batimento de fusão.

5.1.4.3.8. Parassístole Ventricular (PV)

Corresponde ao batimento originado no ventrículo em foco que compete com o ritmo sinusal do coração (marca-passo paralelo que apresenta bloqueio de entrada permanente e de saída ocasional), sendo visível eletrocardiograficamente por apresentar frequência própria, batimentos de fusão e períodos inter-ectópicos com um múltiplo comum e períodos de acoplamento variável. 45

5.1.4.3.9. Fibrilação Ventricular (FV)

Caracteriza-se por ondas bizarras, caóticas, de amplitude e frequência variáveis. Clinicamente, corresponde a uma das formas de apresentação da parada cardiorrespiratória. Este ritmo pode ser precedido de taquicardia ventricular ou Torsade des Pointes , que degeneraram em fibrilação ventricular.

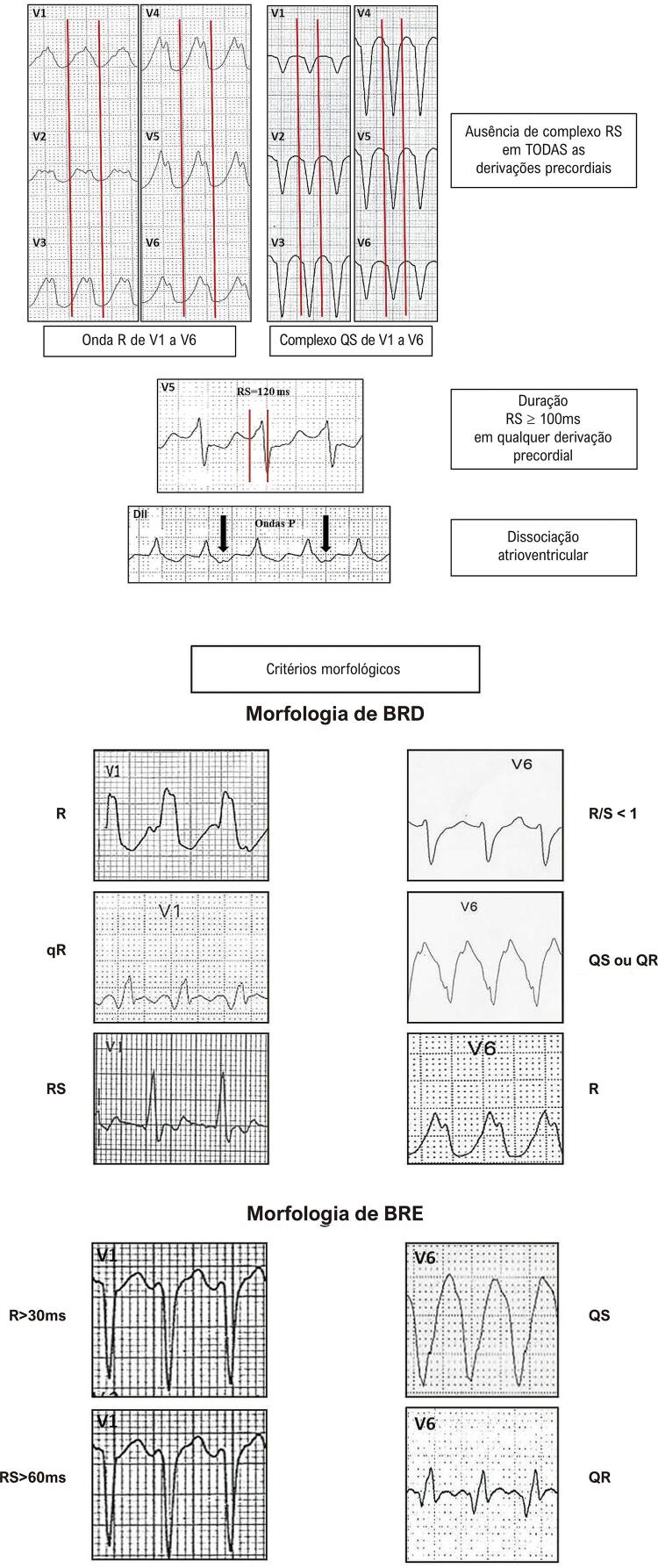

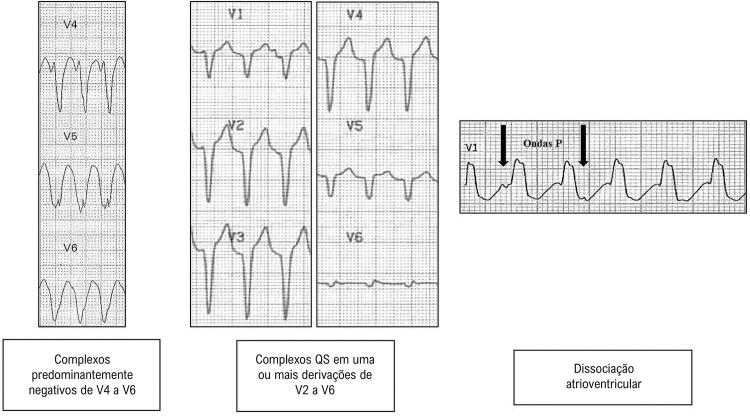

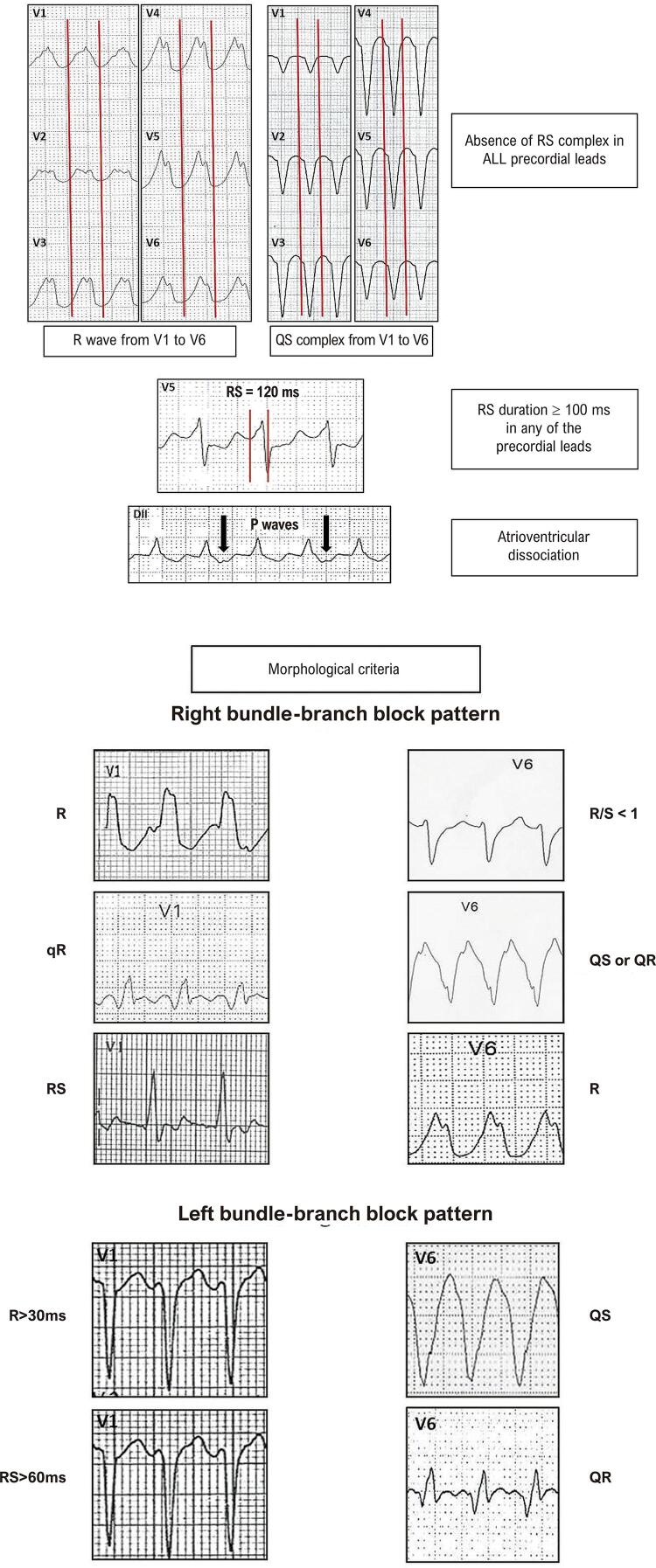

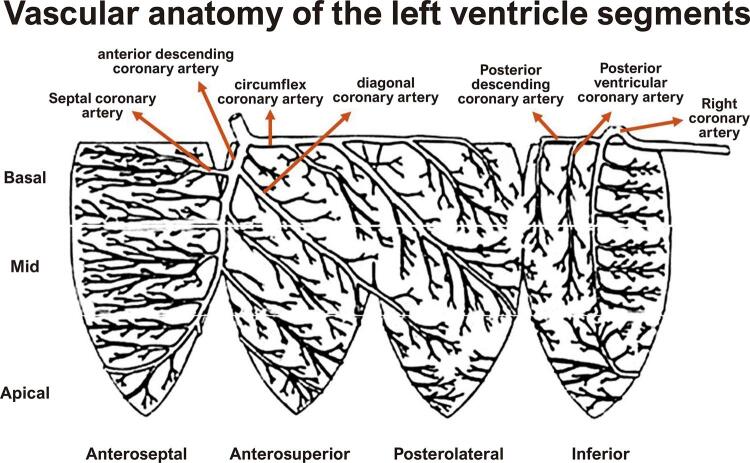

5.1.4.4. Critérios de Diferenciação entre as Taquicardias de Complexo QRS Alargado 46-57

A maioria das taquicardias com complexo QRS largo (80%) é de origem ventricular. A presença de cardiopatia estrutural reforça esta possibilidade. Os achados de dissociação AV (frequência ventricular maior que a atrial), a presença de batimentos de fusão e/ou captura ventricular (com QRS diferente) sugerem fortemente o diagnóstico de TV. Existem algoritmos, como os de Brugada e de Vereckei 48 (mais utilizados), que auxiliam essa diferenciação na ausência desses sinais ( Tabela 5.1 ). 49 - 54 ECG’s com os achados dos critérios de Brugada e Steuer, para o diagnóstico de TV, são exemplificados nas Figuras 5.1 e 5.2, respectivamente.

Tabela 5.1. Critérios eletrocardiográficos para diferenciação entre taquicardia supraventricular com aberrância e taquicardia ventricular.

| Autor | Wellens 49 (1978) | Brugada 46 (1991) | Steuer 51 (1994) | Vereckei 54 (2008) | Pava 55 (2010) | Jastrzebski 56 ou Escore TV (2016) | Santos Neto 57 (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achados e Etapas da Analise para cada Algoritmo | Dissociação AV | Ausência RS precordiais | Complexos QRS predominantemente negativos de V4 a V6 | R inicial aVR | Duração 3 50ms início QRS até pico R em DII | Onda R dominante em V1 | Polaridade predominantemente negativa nas 4 derivações: DI, DII, V1, V6 |

| QRS > 140 ms (BRD) | RS 3 100ms | Complexo QS em uma ou mais derivações de V2 a V6 | r ou q inicial > 40ms | r inicial > 40ms em V1 ou V2 | Polaridade predominantemente negativa em 3 das 4 derivações | ||

| QRS > 160 ms (BRE) | Dissociação AV | Dissociação AV | Entalhe descendente em QRS predominantemente negativo | Entalhe onda S em V1 | Polaridade predominantemente negativa em 2 das 4 derivações | ||

| Eixo QRS além de -30 o | Critérios morfológicos | Relação Vi/Vt ≤ 1 | R inicial aVR | ||||

| QRS mono ou bifásico em V1 (BRD) | Duração ≥50ms início QRS até pico R em DII | ||||||

| QR ou QS em V6 (BRE) | Ausência RS precordiais | ||||||

| Dissociação AV |

Figura 5.1. Exemplos dos quatro critérios de Brugada para o diagnóstico de taquicardia ventricular.

Figura 5.2. Critérios de Steuer para o diagnóstico de taquicardia ventricular.

6. Sobrecargas das Câmaras Cardíacas

6.1. Sobrecargas Atriais

6.1.1. Sobrecarga Atrial Esquerda (SAE)

Aumento da duração da onda P igual ou superior a 120 ms, na derivação D2, com intervalo entre os componentes atriais direito e esquerdo maior ou igual a 40 ms. Onda P com componente negativo aumentado (final lento e profundo) na derivação V1. A área da fase negativa de pelo menos 0,04 mm/s, ou igual ou superior a 1 mm 2 , constitui o Índice de Morris, que apresenta melhor sensibilidade que o critério isolado de duração aumentada.

6.1.2. Sobrecarga Atrial Direita (SAD)

A onda P apresenta-se apiculada com amplitude acima de 0,25 mV ou 2,5 mm. Na derivação V1 apresenta porção inicial positiva > 0,15 mV ou 1,5 mm. São sinais acessórios e indiretos de SAD: Peñaloza-Tranchesi (complexo QRS de baixa voltagem em V1 e que aumenta de amplitude significativamente em V2) e Sodi-Pallares (complexos QR, Qr, qR ou qRS em V1). Raramente isolada, frequentemente é associada à SVD.

6.1.3. Sobrecarga Biatrial (SBA)

Associação dos critérios SAE e SAD.

6.1.4. Sobrecarga Ventricular Esquerda (SVE) 58 - 68

Apesar do ecocardiograma apresentar elevada acurácia na identificação da SVE, o ECG, quando alterado, tem importante significado prognóstico. Dentre os critérios existentes, temos:

6.1.4.1. Critérios de Romhilt-Estes 66

Por este critério existe SVE quando se atinge 5 pontos ou mais no escore que se segue. Dentre as limitações para a utilização deste escore temos a presença de bloqueio de ramo esquerdo e/ou fibrilação atrial, taquicardia atrial, flutter atrial e bloqueio de ramo direito.

Critérios de 3 pontos – aumento de amplitude do QRS (maior ou igual a 20 mm no plano frontal e/ou maior ou igual a 30 mm no plano horizontal); padrão de strain na ausência de ação digitálica; e índice de Morris;

Critério de 2 pontos – desvio do eixo elétrico do QRS além de -30º;

Critérios de 1 ponto – aumento do tempo de ativação ventricular (TAV) ou deflexão intrinsecoide além de 40 ms; aumento da duração do QRS (>90 ms) em V5 e V6; e padrão “ strain” sob ação do digital.

6.1.4.2. Índice de Sokolow Lyon 60

É considerado positivo quando a soma da amplitude da onda S na derivação V1 com a amplitude da onda R da derivação V5/V6 for >35 mm. Nos jovens, este limite pode ser de 40 mm. Não deve ser utilizado em atletas.

6.1.4.3. Índice de Cornell 58

Quando a soma da amplitude da onda R na derivação aVL, com a amplitude da onda S de V3 for >28 mm em homens e 20 mm em mulheres.

6.1.4.4. Peguero-Lo Presti 67 , 68

Este critério é considerado positivo quando a soma da amplitude da maior onda S das 12 derivações com a onda S de V4 é ≥ 28 mm em homens e ≥ 23 mm em mulheres.

6.1.4.5. Alterações de Repolarização Ventricular

Onda T achatada nas derivações esquerdas (D1, aVL, V5 e V6) ou padrão tipo strain (infradesnivelamento do ST ≥ 0,5 mm e onda T negativa e assimétrica).

6.1.5. Sobrecarga Ventricular Direita (SVD) 69 - 72

6.1.5.1. Eixo do QRS

Eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal, localizado à direita de +110º no adulto.

6.1.5.2. Onda R Ampla

Presença de onda R de alta voltagem em V1 e V2 e ondas S profundas nas derivações opostas (V5 e V6).

6.1.5.3. Morfologia qR ou qRs

A morfologia qR ou qRs em V1 (ou V1 e V2) é um dos sinais mais específicos de SVD e apontam sobrecarga ventricular direita sistólica com aumento da pressão intraventricular.

6.1.5.4. Morfologia rsR’

Padrão trifásico (rsR’), com onda R‘ proeminente nas precordiais direitas V1 e V2 e sugere sobrecarga ventricular diastólica com aumento do volume da câmara.

6.1.5.5. Repolarização Ventricular

Padrão strain de repolarização nas precordiais direitas (V1, V2 e, às vezes, V3) (infradesnivelamento do segmento ST acompanhado da onda T negativa).

6.1.5.6. Critério de SEATTLE para SVD

Soma de R de V1 + S V5-V6 >10,5 mm (e desvio de eixo à direita >120°).

6.1.6. Sobrecarga Biventricular

Eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal desviado para a direita, associado a critérios de voltagem para SVE;

- ECG típico de SVD, associado a um ou mais dos seguintes elementos:

- b.1) Ondas Q profundas em V5 e V6 e nas derivações inferiores;

- b.2) R de voltagem aumentada em V5 e V6;

- b.3) S de V1 e V2 + R de V5 e V6 com critério positivo de Sokolow;

- b.4) Deflexão intrinsecoide em V6 igual ou maior que 40 ms;

Complexos QRS isodifásicos amplos, de tipo R/S > 50 mm, nas precordiais intermediárias de V2 a V4 (fenômeno de Katz-Wachtel).

6.1.7. Diagnóstico Diferencial do Aumento de Amplitude do QRS 73

A sobrecarga ventricular é a situação onde mais comumente ocorre o aumento da amplitude do QRS. No entanto, o QRS pode estar aumentado em indivíduos normais nas seguintes situações:

Crianças, adolescentes e adultos jovens;

Longilíneos;

Atletas;

Mulheres mastectomizadas;

Vagotonia.

7. Análise dos Bloqueios (Retardo, Atraso de Condução) Intraventriculares

7.1. Bloqueios Intraventriculares 74 , 75

Embora a denominação “bloqueio de ramo” esteja bem estabelecida na literatura, o que ocorre são diversos graus de atrasos na propagação intraventricular dos impulsos elétricos, determinando mudanças na forma e na duração do complexo QRS. Essas mudanças na condução intraventricular podem ser fixas ou intermitentes, frequência-dependentes. Os bloqueios podem ser causados por alterações estruturais do sistema de condução His-Purkinje ou do miocárdio ventricular (necrose, fibrose, calcificação, lesões infiltrativas ou pela insuficiência vascular), ou funcionais, devido ao período refratário relativo de parte do sistema de condução gerando a aberrância da condução intraventricular.

7.1.1. Bloqueio do Ramo Esquerdo (BRE) 76 , 77

a) QRS alargados com duração ≥120 ms como condição fundamental (as manifestações clássicas do BRE, contudo, expressam-se em durações iguais ou superiores a 130 ms para mulheres e iguais ou superiores a 140 ms para homens);

Ausência de “q” em D1, aVL, V5 e V6; variantes podem ter onda “q” apenas em aVL;

Ondas R alargadas e com entalhes e/ou empastamentos médio-terminais em D1, aVL, V5 e V6;

Onda “r” com crescimento lento de V1 a V3, podendo ocorrer QS;

Deflexão intrinsecoide em V5 e V6 ≥50 ms;

Eixo elétrico de QRS entre -30° e +60°;

Depressão de ST e T assimétrica em oposição ao retardo médio-terminal.

7.1.1.1. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo em Associação com Sobrecarga Ventricular Esquerda 78 - 79

O diagnóstico eletrocardiográfico de sobrecarga ventricular esquerda, em associação ao bloqueio de ramo esquerdo, não é simples devido às modificações do complexo QRS inerentes ao BRE. Os estudos mostram resultados variáveis sobre a acurácia dos critérios eletrocardiográficos para SVE.

Sobrecarga atrial esquerda;

Duração do QRS >150 ms;

Onda R em aVL >11 mm;

Ondas S em V2 >30 mm e em V3 >25 mm;

SÂQRS além de -40° graus;

Presença de Índice de Sokolow-Lyon ≥35 mm.

7.1.1.2. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo em Associação com Sobrecarga Ventricular Direita 80 (ao Menos 2 dos 3 Critérios)

Baixa voltagem nas derivações precordiais;

Onda R proeminente terminal em aVR;

Relação R/S em V5 menor que 1.

7.1.2. Bloqueio do Ramo Direito (BRD) 81 , 82

QRS alargados com duração ≥120 ms como condição fundamental;

Ondas S empastadas em D1, aVL, V5 e V6;

Ondas qR em aVR com R empastada;

rSR’ ou rsR’ em V1 com R’ espessado;

Eixo elétrico de QRS variável, tendendo para a direita no plano frontal;

Onda T assimétrica em oposição ao retardo final de QRS.

7.1.2.1. Atraso Final de Condução

A expressão atraso final de condução poderá ser usada quando o distúrbio de condução no ramo direito for muito discreto. Pode ser uma variante dos padrões de normalidade.

7.1.3. Bloqueios Divisionais do Ramo Esquerdo 83 - 92

A presença de atraso que acomete, além do ramo esquerdo (tronco), as divisões deste, podem gerar desvios do SÂQRS para cima/esquerda (BDAS) ou para a baixo/direita (BDPI).

7.1.3.1 Bloqueio Divisional Anterossuperior Esquerdo (BDAS) 83 - 87

Eixo elétrico de QRS ≥ -45°;

rS em D2, D3 e aVF com S3 maior que S2; QRS com duração <120 ms;

Onda S de D3 com amplitude maior ou igual a 15 mm;

qR em D1 e aVL com tempo da deflexão intrinsecoide ≥ 50 ms ou qRs com “s” mínima em D1;

qR em aVL com R empastado;

Progressão lenta da onda r de V1 até V3;

Presença de S de V4 a V6.

7.1.3.2. Bloqueio Divisional Anteromedial Esquerdo (BDAM) 88 - 90

Morfologia qR em V1 a V4;

Onda R ≥15 mm em V2 e V3 ou desde V1, crescendo para as derivações precordiais intermediárias e diminuindo de V5 para V6;

Salto de crescimento súbito da onda “r” de V1 para V2 (“rS” em V1 para R em V2);

Duração do QRS <120 ms;

Ausência de desvio do eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal;

Ondas T, em geral negativas nas derivações precordiais direitas.

Todos esses critérios são válidos na ausência de SVD, hipertrofia septal ou infarto lateral.

7.1.3.3. Bloqueio Divisional Posteroinferior Esquerdo (BDPI) 83 - 85 , 91 , 92

Eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal orientado para a direita >+90°;

qR em D2, D3 e aVF com R3>R2 e deflexão intrinsecoide >50 ms;

Onda R em D3 >15 mm (ou área equivalente);

Tempo de deflexão intrinsecoide aumentado em aVF, V5-V6 maior ou igual a 50 ms;

rS em D1 com duração <120 ms; podendo ocorrer progressão mais lenta de “r” de V1 – V3;

Onda S de V2 a V6.

Todos esses critérios são validos na ausência de tipo constitucional longilíneo, SVD e área eletricamente inativa lateral. 80 , 91

7.1.4. Bloqueios Divisionais do Ramo Direito 82

7.1.4.1. Bloqueio Divisional Superior Direito (BDSRD)

rS em D2, D3 e aVF com S2>S3 (o que diferencia do BDAS do ramo esquerdo);

Rs em D1 com onda s>2mm, rS em D1 ou D1, D2 e D3 (S1,S2,S3) com duração <120 ms;

S empastado em V1- V2 / V5 – V6 ou, eventualmente, rSr’ em V1 e V2;

qR em avR com R empastado.

7.1.4.2. Bloqueio Divisional Inferior Direito (BDIRD)

Onda R em D2 > onda R de D3;

rS em D1 com duração <120 ms;

Eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal orientado para a direita >+90°;

S empastado em V1 - V2 / V5 - V6 ou, eventualmente, rSr’ em V1 e V2;

qR em aVR com R empastado.

Na dificuldade de reconhecimentos dos bloqueios divisionais direitos, pode ser utilizado o termo “atraso final da condução intraventricular”.

7.1.5. Associação de Bloqueios 93

7.1.5.1. BRE Associado ao BDAS

Bloqueio do ramo esquerdo com eixo elétrico de QRS no plano frontal orientado para esquerda, além de -30°, sugere a presença de BDAS.

7.1.5.2. BRE Associado ao BDPI

Bloqueio do ramo esquerdo com eixo elétrico de QRS desviado para a direita e para baixo, além de + 60°, sugere associação com BDPI, ou SVD, ou cardiopatia congênita.

7.1.5.3. BRD Associado ao BDAS

Bloqueio do ramo direito associado ao bloqueio divisional anterossuperior do ramo esquerdo - padrões comuns aos bloqueios descritos individualmente. 94 , 95

7.1.5.4. BRD Associado ao BDPI

Bloqueio do ramo direito associado ao bloqueio divisional posteroinferior do ramo esquerdo – padrões comuns aos bloqueios descritos individualmente; suspeita-se desta associação quando o SÂQRS encontra-se a + 120° ou mais para a direita.

7.1.5.5. BRD Associado ao BDAS e BDAM

Bloqueio de ramo direito associado ao bloqueio divisional anteromedial e anterossuperior – os padrões para estas associações seguem os mesmos critérios para os bloqueios individualmente.

7.1.5.6. BDAS Associado ao BDAM

Esta associação segue os mesmos critérios para os bloqueios individualmente.

7.1.5.7. Bloqueio de Ramo Mascarado 96 , 97

Bloqueio de ramo direito mais comumente com morfologia de R ou rR´ em V1 associado à morfologia de bloqueio de ramo esquerdo com BDAS esquerdo nas derivações do plano frontal. A onda s de D1 habitualmente está ausente ou não é maior que 1 mm.

Na presença das associações acima descritas, observa-se habitualmente acentuação nos desvios dos eixos.

7.1.6. Situações Especiais Envolvendo a Condução Intraventricular

7.1.6.1. Bloqueio Peri-infarto 98

Aumento da duração do complexo QRS na presença de uma onda Q anormal devido ao infarto do miocárdio nas derivações inferiores ou laterais, com aumento da porção final do complexo QRS e de oposição à onda Q (isto é, complexo QR).

7.1.6.2. Bloqueio Peri-isquemia 98 , 99

Quando há um aumento transitório na duração do complexo QRS acompanhado do desvio do segmento ST visto na fase aguda.

7.1.6.3. Fragmentação do QRS (fQRS) 99 , 100

Presença de entalhes na onda R ou S em 2 derivações contíguas na ausência de bloqueio de ramo, ou quando na presença deste, o encontro de mais de 2 entalhes. Na presença de QRS estreito é melhor visualizada nas derivações inferiores principalmente D3 e aVF. Este diagnóstico deve ser muito bem avaliado quando aparece na onda S em V1 e V2 (deve ser diferenciado dos atrasos finais de condução). Quanto maior o número de derivações com fragmentação, pior o prognóstico.

7.1.6.4. Bloqueio de Ramo Esquerdo Atípico 101

Quando da ocorrência de infarto em paciente com bloqueio de ramo esquerdo prévio, temos a presença de ondas Q profundas e largas, padrão QS em V1-V4 e QR em V5-V6, com fragmentação do QRS.

7.1.6.5. Bloqueio Intraventricular Parietal ou Purkinje/Músculo ou Focal 102

Quando o distúrbio dromotrópico localiza-se entre as fibras de Purkinje e músculo, observado em grandes hipertrofias e cardiomiopatias. Pode associar-se ao BDAS esquerdo ou SVE e a duração do QRS ≥120 ms sem apresentar morfologia de BRE ou BRE com BDAS esquerdo.

8. Análise do ECG nas Coronariopatias

Importante salientar que o ECG normal não exclui a presença de evento coronário, devendo-se seguir a orientação clínica específica para síndromes coronarianas agudas. 103 , 104

8.1. Critérios Diagnósticos da Presença de Isquemia Miocárdica 105

8.1.1. Presença de Isquemia

Fase hiperaguda – onda T apiculada e simétrica como apresentação inicial;

Isquemia subendocárdica – Presença de onda T positiva, simétrica e pontiaguda;

Isquemia subepicárdica – Presença de onda T negativa, simétrica e pontiaguda; atualmente atribui-se a esta alteração um padrão de reperfusão ou edema e não mais correspondendo a uma isquemia real da região subepicárdica. 106

8.1.2. Isquemia Circunferencial ou Global 107 , 108

Situação peculiar durante episódio de angina com infradesnível do segmento ST em seis ou mais derivações, com maior intensidade em V4 a V6 acompanhado de ondas T negativas, em associação a supradesnivelamento ST > 0,5mm em aVR.

8.1.3. Alterações Secundárias

São chamadas de alterações secundárias da onda T aquelas que não se enquadram na definição de ondas isquêmicas em especial pela assimetria e pela presença de outras características diagnósticas como as das sobrecargas cavitárias ou bloqueios intraventriculares.

8.2. Critérios Diagnósticos da Presença de Lesão

lesão subepicárdica – elevação do ponto J e do segmento ST, com concavidade ou convexidade (mais específica) superior deste segmento em 2 derivações contíguas que exploram a região envolvida, de pelo menos 1 mm no plano frontal e precordiais esquerdas. Para as derivações precordias V1 a V3, considerar em mulheres ≥1,5 mm, em homens acima de 40 anos ≥2,0 mm e abaixo de 40 anos ≥2,5 mm de supradesnivelamento ST; 109

lesão subendocárdica 109 – depressão do ponto J e do segmento ST, horizontal ou descendente ≥0,5 mm em 2 derivações contíguas que exploram as regiões envolvidas, aferido 60 ms após o ponto J.

Observação: o diagnóstico da corrente de lesão leva em consideração a presença concomitante de alterações da onda T e do segmento ST reconhecidas em pelo menos duas derivações concordantes.

8.3. Definição das Áreas Eletricamente Inativas (AEI)

Considera-se área eletricamente inativa aquela onde não existe ativação ventricular da forma esperada, sem configurar distúrbio de condução intraventricular. É caracterizada pela presença de ondas Q patológicas em duas derivações contíguas, com duração igual ou superior a 40 ms, associadas ou não à amplitude > 25% de todo QRS ou redução da onda R em área onde a mesma é esperada e deveria estar presente.

8.4. Análise Topográfica da Isquemia, Lesão e Necrose

8.4.1. Análise Topográfica das Manifestações Isquêmicas ao ECG (Meyers)

Parede anterosseptal – Derivações V1, V2, V3;

Parede anterior – Derivações V1, V2, V3 e V4;

Parede anterior localizada – Derivações V3, V4 ou V3-V5;

Parede anterolateral – Derivações V4 a V5, V6, D1 e aVL;

Parede anterior extensa – V1 a V6 , D1 e aVL;

Parede lateral – Derivações V5 e V6.

Parede lateral alta – D1 e aVL;

Parede inferior – D2, D3 e aVF.

Obs.: Os termos “parede posterior” e “dorsal” não deverão mais ser utilizados, em vista das evidências atuais de que o registro obtido por V7 a V9 refere-se à parede lateral. 110

8.4.2. Análise topográfica das manifestações isquêmicas pelo ECG em associação à ressonância magnética 111

Parede septal – Q em V1 e V2;

Parede anteroapical – Q em V1, V2 até V3-V6;

Parede anterior média (anteromedial) – Q (qs ou r) em D1, aVL e, às vezes, V2 e V3;

Parede lateral – Q (qr ou r) em D1, aVL, V5-V6 e/ou RS em V1;

Parede inferior – Q em D2, D3 e aVF.

Essas localizações apresentam melhor correlação anatômica nas síndromes coronárias agudas com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST e na necrose, quando presente. As localizações topográficas, descritas acima, podem apresentar variações em virtude de cardiomegalia ou alterações estruturais importantes.

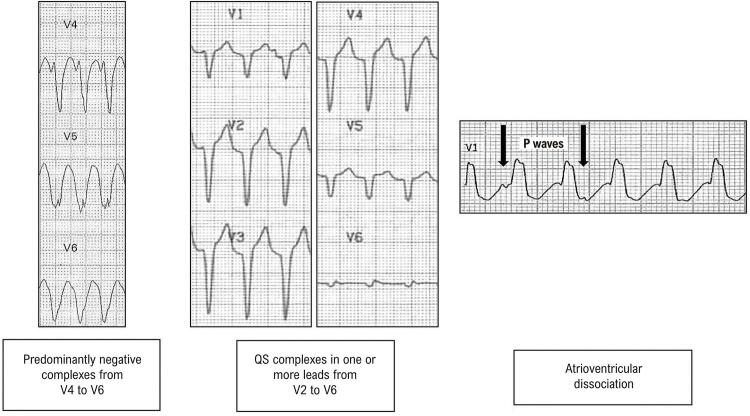

8.4.3. Correlação Eletrocardiográfica com a Artéria Envolvida ( Tabela 8.1 ) 112

Tabela 8.1. – Correlação entre derivações eletrocardiográficas e artéria culpada.

| Supra ST | Infra ST | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tronco coronária esquerda | aVR | V2-V6; I,L | |||

| Descendente anterior | antes da 1 a septal | V1 - V4 | I, L | II, III, F | |

| Descendente anterior | entre septal e diagonal | V1 - V6 | I, L | ||

| Descendente anterior longa (após crux cordis) | após septal e diagonal | V2 - V6 | I, L | V2-V6; I,L | |

| Coronária direita proximal | V4 - V6 | II < III, F | I, L, V1 - V3 | ||

| Coronária direita médio/distal | II < III, F | I, L | I, L, V1 - V3 | ||

| Coronária direita distal | II < III, F | I, L | |||

| Coronária direita (ventrículo direito) | V1, V3R, V4R | II < III, F | |||

| Circunflexa | V4 - V6 | II > III, F | I, L | V1 - V3 | |

| Circunflexa (ventrículo direito) | V1, V3R, V4R; V4 - V6 | II > III, F | I, L | ||

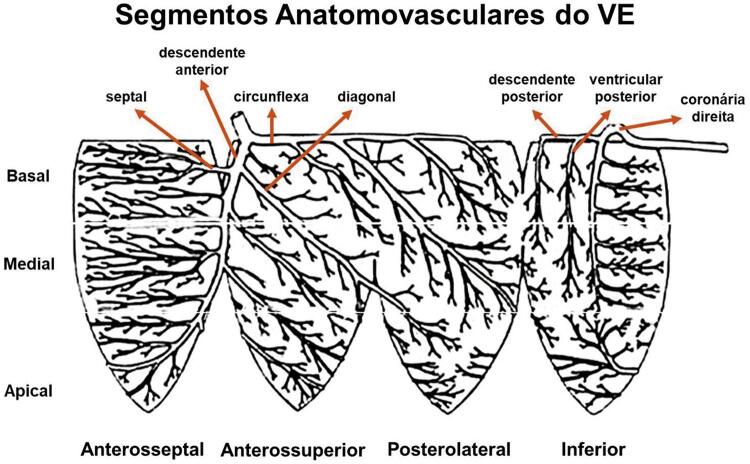

Na Figura 8.1 , encontramos a correlação entre a artéria culpada e o segmento/parede ventricular envolvido.

Figura 8.1. Correlação entre artéria envolvida e parede/segmento ventricular (modificado de Selvester RH et al.) 112 .

8.5. Infartos de Localização Especial

8.5.1. Infarto do Miocárdio de Ventrículo Direito

Elevação do segmento ST em derivações precordiais direitas (V1, V3R, V4R, V5R e V6R), particularmente com elevação do segmento ST superior a >1 mm em V4R. A elevação do segmento ST nos infartos do VD aparece por um curto espaço de tempo devido ao baixo consumo de oxigênio da musculatura do VD. Geralmente, este infarto associa-se ao infarto da parede inferior e/ou lateral do ventrículo esquerdo. 113

8.5.2. Infarto Atrial

Visível pela presença de desnivelamentos do segmento PR maiores que 0,5 mm. Pode associar-se a arritmias atriais. 114

8.6. Diagnósticos Diferenciais 115

8.6.1. Isquemia Subepicárdica

Isquemia subepicárdica deve ser diferenciada das alterações secundárias da repolarização ventricular em SVE ou bloqueios de ramos (aspecto assimétrico da onda T).

8.6.2. Infarto Agudo do Miocárdio (IAM) com Supra de ST

O infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM) com supra de ST deve ser diferenciado das seguintes situações:

repolarização precoce;

pericardite e miocardite;

IAM antigo com área discinética e supradesnível persistente (aneurisma do ventrículo esquerdo);

alguns quadros abdominais agudos como pancreatite;

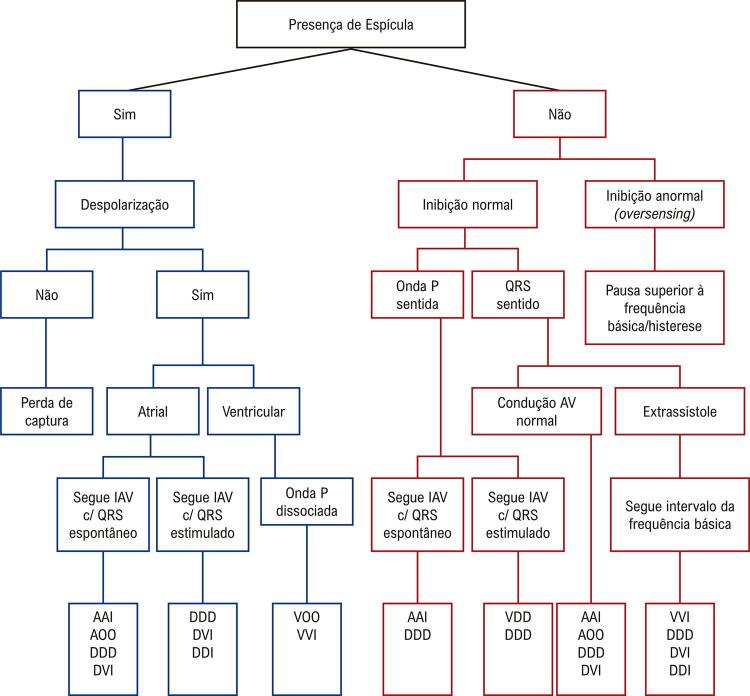

hiperpotassemia;