Abstract

Introduction

Surgical complications after primary or interval debulking surgery in advanced ovarian cancer were investigated and associations with patient characteristics and surgical outcomes were explored.

Material and methods

A population‐based cohort study including all women with ovarian cancer, FIGO III–IV, treated with primary or interval debulking surgery, 2013–2017. Patient characteristics, surgical outcomes and complications according to the Clavien–Dindo (CD) classification system ≤30 days postoperatively, were registered. Uni‐ and multivariable regression analyses were performed with severe complications (CD ≥ III) as endpoint. PFS in relation was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

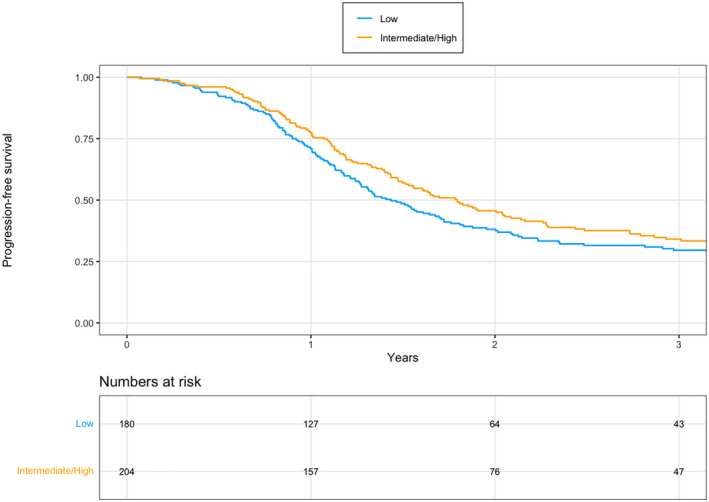

The cohort included 384 women, where 304 (79%) were treated with primary and 80 (21%) with interval debulking surgery. Complications CD I–V were registered in 112 (29%) patients and CD ≥ III in 42 (11%). Preoperative albumin was significantly lower in the CD ≥ III cohort compared with CD 0–II (P = 0.018). For every increase per unit in albumin, the risk of complications decreased by a factor of 0.93. There was no significant difference in completed chemotherapy between the cohorts CD 0–II 90.1% and CD ≥ III 83.3% (P = 0.236). In the univariable analysis; albumin <30 g/L, primary debulking surgery, complete cytoreduction and intermediate/high surgical complexity score (SCS) were associated with CD ≥ III. In the following multivariable analysis, only intermediate/high SCS was found to be an independent significant prognostic factor. Low (n = 180) vs intermediate/high SCS (n = 204) showed a median PFS of 17.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 15.2–20.7) vs 21.5 months (95% CI 18.2–25.7), respectively, with a significant log‐rank; P = 0.038.

Conclusions

Advanced ovarian cancer surgery is associated with complications but no significant difference was seen in completion of adjuvant chemotherapy when severe complications occur. Importantly, our study shows that intermediate/high SCS is an independent prognostic risk factor for complications. Low albumin, residual disease and primary debulking surgery were found to be associated with severe complications. These results may facilitate forming algorithms in the decision‐making procedure of surgical treatment protocols.

Keywords: debulking, epidemiology, ovarian cancer, postoperative complications, residual disease, surgery, survival

Abbreviations

- CD

Clavien–Dindo

- CI

confidence interval

- FIGO

Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d'Obstetrique

- IDS

interval debulking surgery

- NACT

neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- PDS

primary debulking surgery

- PFS

progression‐free survival

- SCS

surgical complexity score

- SQRGC

Swedish Quality Register for Gynecological Cancer

Key message.

Advanced ovarian cancer surgery is associated with complications where albumin was found to be a predictor and surgical complexity score an independent prognostic risk factor. Importantly, severe complications do not appear to affect completion of adjuvant chemotherapy.

1. INTRODUCTION

A major management shift has taken place during the last decades in the surgical treatment of advanced ovarian cancer, with emphasis on radical debulking surgery performed by experienced surgeons. With more complex and radical debulking surgery, aiming for complete cytoreduction with no residual disease (R0), it is conceivable that complications may increase and affect the following adjuvant treatment. Previous studies have tried to investigate whether complications increased as surgery became more complex. These studies seem to agree that the proportion of complications is associated with complex surgeries, but uncertainty remains as to whether this will affect survival. 1 , 2 , 3 However, every severe complication entails suffering for the patient and potentially delays the time to adjuvant chemotherapy. Importantly, such a delayed start of chemotherapy has been shown to impair overall survival. 4

First line treatment for ovarian cancer is considered to be primary debulking surgery (PDS), followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and, in selected cases, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by interval debulking surgery (IDS). 5 The surgical aim is to increase the number of patients for whom complete cytoreduction is achieved, minimize surgical complications and potentially reduce short‐time mortality/morbidity. 6 , 7 , 8 There is an ongoing debate concerning which type of surgery is preferable to provide as effective a treatment as possible with minimal complications. 3 , 9 An appealing idea is to evaluate every patient prior to surgery using certain parameters to predict who would be at too high a risk for complications and choose treatment based on a risk calculation. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology recently published guidelines for the perioperative management of advanced surgery, recommending an individual risk assessment prior to surgery and suggesting a number of perioperative strategies to minimize the risk of adverse events. 10 Researchers have suggested potential risk factors associated with complications such as obesity, albumin level, number of surgical procedures performed and age. 2 , 11 , 12 , 13 Nevertheless, these are still unclear and further studies are needed to identify clinically useful predictors identifying which patient benefits from advanced surgery in order to reduce the number of complications and possibly increase survival.

The aim of this study was to investigate and assess complications after surgery for advanced stages of ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer in a complete population‐based cohort and the to identify possible associations between severe complications and patient characteristics, valuable when designing individual treatment protocols. These results would enhance our knowledge concerning surgical side effects and minimize the risk of severe complications and improve outcome.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Data source

This is a regional population‐based cohort study based on prospectively and consequently registered data from the Swedish Quality Register for Gynecological Cancer (SQRGC). The SQRGC started in 2008 and has close to 100% coverage every year in the Western Sweden healthcare region compared with the Swedish National Cancer Registry. Reporting to the Swedish National Cancer Registry is mandatory and since all citizens in Sweden have a personal identification number, all diagnosed individuals can be found. The Swedish National Cancer Registry has over 95% coverage of all malignant tumors, 99% are morphologically verified. 14 Predefined variables possibly associated with complications were identified and registered and were chosen according to previous studies and clinical experience. 2 , 11 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 A majority of the predefined variables could be retrieved directly from the SQRGC. When a variable was missing in the registry, two doctors completed the dataset by reviewing medical records. The predefined variables added through medical records by one doctor were: preoperative albumin level, body mass index, smoking and details about the complications. Patients were followed until November 2020 or death, whichever came first. Time of death was collected from the Swedish national population register.

The Western Sweden healthcare region (1.9 million inhabitants) has one tertiary hospital, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, and the primary treatment of advanced ovarian cancer was centralized in 2011.

2.2. Study cohort and clinical variables

All women ≥ 18 years registered in the SQRGC and diagnosed with ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer, Federation Internationale de Gynaecologie et d'Obstetrique (FIGO) stage III and IV where PDS or IDS had been performed between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2017 were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria were if PDS or IDS registered in the SQRGC were considered emergency surgery or surgery intended for diagnosis only when reviewed. Staging was performed by the FIGO classification from 1988 to 2013 and from 2014 for the following years. 19 Categorization concerning the degree of surgery was performed according to Aletti and grouped into low (0–3), intermediate (4–7) and high (≥8) surgical complexity score (SCS). 1 The gynecologic oncology surgeon responsible, registered whether complete cytoreduction (R0) was achieved or not (R > 0) into the SQRGC at the time of surgery.

Body mass index was calculated from the weight measured closest to surgery and registered in the medical records, but not earlier than a month before surgery. The latest albumin during the month before surgery was included. Albumin <30 g/L was considered low in our uni‐ and multivariable analyses and the cut‐off level was chosen since it has been used in previous exploring studies. 2 , 17 Only current smoking was recorded; ex‐smokers were considered non‐smokers. The patient's health status prior to surgery was recorded according to the World Health Organization performance status and registered in the SQRGC at the time of surgery. Length of hospital stay was defined as the number of full days from surgery to hospital discharge to home.

Most women treated with PDS received adjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin AUC 5 and paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 intravenously every third week for six cycles, with the aim to start chemotherapy within 21 days of surgery. The treatment was evaluated at cycles 3 and 6. Women treated with NACT had IDS performed after three to four cycles of chemotherapy. Treatment was planned according to the Swedish national guidelines. 20 Bevacizumab was implemented in 2013 for women with residual disease at PDS or IDS and for high‐risk patients in accordance to the results of the ICON‐7 study. 21 , 22 First line chemotherapy was categorized into five subgroups: “Platinum Taxane combination+Platinum other”, “Platinum Taxane Bevacizumab combination”, “Non‐Platinum”, “No chemotherapy” and “Missing.” “Platinum other” is a combination of those treated with only carboplatin, those who received only carboplatin initially where paclitaxel was added later and those who had an allergic reaction to paclitaxel after a few cycles.

2.3. Complications

To classify surgical complications, the Clavien–Dindo (CD) classification system was used. 23 Complications CD 0–II were compared with CD ≥ III in the statistical assessment, since severe complications, defined as CD ≥ III, were considered the most clinically relevant. Complications within 30 days of surgery were included to try to exclude chemotherapy effects on complications. Each patient's worst complication was extracted from the SQRGC, validated through medical records and categorized.

2.4. Survival

Progression‐free survival (PFS) of 3 years, to register the complete cohort, was chosen as a measure of survival defined as time to progression, recurrence or death. If there was no information about progression/recurrence in the SQRGC, one gynecologic oncology surgeon reviewed the medical records to investigate whether there was progression/recurrence and to specify the progression/recurrence date. Data on progression/recurrence was recorded in November 2020 and defined using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in combination with CA‐125. Mortality within 90 days after surgery was analyzed in the complete cohort and collected from the Swedish national population register.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Three‐year PFS was calculated comparing low vs intermediate/high SCS and PDS vs IDS, with 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Kaplan–Meier method. Log‐rank type test was used to test the difference in PFS between cohorts. Welch's t‐test, Chi‐square test and Fisher's test were used to test associations between groups. Chi‐square and Fisher's test were used for categorical variables and Welch's t‐test for continuous variables. If data was missing, that patient was excluded from that variable analysis. A result was considered statistically significant if the P‐value was <0.05 with a two‐sided test. To estimate the probability of complications, we used a logistic regression model; univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression were performed to evaluate effect and potential risk factors for severe complications. The program used for statistical calculations was R statistical software version 4.0.3.

3. RESULTS

In total, 405 women were identified in the SQRGC with advanced stages of ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer (hereafter referred to as ovarian cancer), eight (2.0%) of whom were excluded due to no surgical treatment and 13 (3.2%) since only explorative surgery had been performed without tumor resection, for example emergency ileus or diagnostic surgery. There were 384 patients treated with PDS or IDS who were included in the final study cohort and‐further analyzed. Patient and tumor characteristics are presented in detail in Table 1. Categorization of surgery was performed according to Aletti and modified to suit the surgical procedures performed in the study, described in Table 2. In the total cohort of 384 women, 121 (31.5%) upper abdominal surgeries were performed.

TABLE 1.

Clinical patient characteristics of surgically treated advanced ovarian cancer, 2013–2017

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 384 (100) |

| Median age, years (range) | 66.0 (20.0–89.0) |

| Preoperative WHO performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 86 (22.4) |

| 1 | 235 (61.2) |

| 2 | 53 (13.8) |

| 3 | 7 (1.8) |

| 4 | 2 (0.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Median preoperative CA‐125, units/ml (range) | 523 (3–48 000) |

| Missing, n (%) | 30 (7.8) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |

| Yes | 35 (9.1) |

| No | 329 (85.7) |

| Missing | 20 (5.2) |

| Preoperative BMI, n (%) | |

| <19 | 15 (3.9) |

| 19–29 | 282 (73.4) |

| ≥30 | 65 (16.9) |

| Missing | 22 (5.7) |

| Median preoperative albumin, g/L (range) | 35.0 (16.0–46.0) |

| Missing | 63 (16.4) |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | |

| IIIA | 15 (3.9) |

| IIIB | 9 (2.3) |

| IIIC | 275 (71.6) |

| IV | 84 (21.9) |

| X | 1 (0.3) |

| Primary surgery, n (%) | |

| PDS | 304 (79.2) |

| IDS | 80 (20.8) |

| Complete cytoreduction at PDS or IDS, n (%) | |

| Yes (R0) | 187 (48.7) |

| No (R >0) | 196 (51.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Operating hospital, n (%) | |

| Tertiary hospital | 290 (75.5) |

| County hospital | 94 (24.5) |

| Surgical complexity score, n (%) | |

| Low | 180 (46.9) |

| Intermediate | 141 (36.7) |

| High | 63 (16.4) |

| Median length of hospital stay, days (range) | 8.0 (0–145) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| 1st line chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Platinum Taxane combination+Platinum other | 296 (77.1) |

| Platinum Taxane Bevacizumab combination | 76 (19.8) |

| Non‐Platinum | 2 (0.5) |

| No chemotherapy | 7 (1.8) |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) |

| Completed 1st line chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 343 (89.3) |

| No | 32 (8.3) |

| No chemotherapy | 7 (1.8) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) |

| Number of complications within 30 days of surgery, n (%) | |

| Clavien–Dindo 0 | 272 (70.8) |

| Clavien–Dindo I–II | 70 (18.2) |

| Clavien–Dindo IIIA | 22 (5.7) |

| Clavien–Dindo IIIB | 14 (3.6) |

| Clavien–Dindo IVA | 3 (0.8) |

| Clavien–Dindo IVB | 2 (0.5) |

| Clavien–Dindo V | 1 (0.3) |

| 90‐Day mortality, n (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (1.0) |

| No | 380 (99.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IDS, interval debulking surgery; PDS, primary debulking surgery; WHO, World Health Organization.

TABLE 2.

Modified Aletti surgical complexity score

| 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points |

| Hysterectomy and salpingo‐oophorectomy | Cholecystectomy | Rectum amputation | Total peritonectomy |

| Appendectomy | Colon resection | Liver segment resection | |

| Lymph node dissection, pelvic | Partial gastrectomy | Cystectomy | |

| Lymph node dissection, inguinal | Splenectomy | Pancreatic resection | |

| Lymph node dissection, paraaortic | Liver resection | ||

| Omentectomy | Bladder resection | ||

| Peritonectomy, abdomen | Diaphragm resection | ||

| Peritonectomy, pelvis | Nephrectomy | ||

| Resection small intestine | Peritonectomy, diaphragm | ||

| Umbilical hernia repair | |||

| Abdominal wall reconstruction |

3.1. Complications

In the final study cohort 304 (79%) women were treated with PDS and 80 (21%) with IDS. There was a total of 112 (29%) CD I–V complications registered and 42 (11%) complications graded as CD ≥ III within 30 days of surgery in the complete cohort. Detailed descriptions concerning all complications CD ≥ III are described in Table 3. There were 36 complications categorized as CD III, five as CD IV and one death, CD V (Table 3). The most common complication was pleural fluid with drainage, 4.2% (n = 16).

TABLE 3.

Description of most severe complication per patient within 30 days of surgery

| Total n = 384 (%) | |

| CD classification | |

| CD 0–II | 342 (89.1) |

| CD ≥ III | 42 (10.9) |

| Description complications CD III–V | |

| CD IIIA | 22 (5.7) |

| Pleural fluid, drainage | 16 (4.2) |

| Hydronephrosis, nephrostomy | 2 (0.5) |

| Wound resutured in LA | 1 (0.3) |

| Wound seroma, drainage in LA | 1 (0.3) |

| Wound infection, cleansed in LA | 2 (0.5) |

| CD IIIB | 14 (3.6) |

| Intraabdominal bleeding, surgical intervention | 2 (0.5) |

| Intraabdominal abscess, drainage | 1 (0.3) |

| Vaginal vault abscess, drainage | 2 (0.5) |

| Wound hematoma, resutured | 1 (0.3) |

| Wound dehiscence, resutured | 2 (0.5) |

| Intra‐abdominal abscess, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| Stoma necrosis, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| Urinary tract injury, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| Intraabdominal abscess and bleeding, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| Suspected anastomosis leakage, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| Anastomosis leakage, surgical intervention | 1 (0.3) |

| CD IVA | 3 (0.8) |

| Bleeding diaphragm, surgical intervention, intensive care | 1 (0.3) |

| Pulmonary failure, intensive care | 2 (0.5) |

| CD IVB | 2 (0.5) |

| Anastomosis leakage, surgical intervention, intensive care | 1 (0.3) |

| Sepsis, multiple organ failure, intensive care | 1 (0.3) |

| CD V | 1 (0.3) |

| Sepsis, multiple organ failure, cardiac arrest | 1 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: CD, Clavien–Dindo; LA, local anesthesia.

Patient and disease characteristics in the cohort with no or mild complications, defined as CD 0–II (n = 342), were compared with those in patients with severe complications (CD ≥ III) (n = 42) and results are shown in detail in Table 4. There was a tendency that women with severe complications were younger with a median age of 63.5 years compared with the CD 0–II group with a median age of 66.5 years, although the difference was not statistically significant.

TABLE 4.

Clinical characteristics of complications CD 0–II vs CD ≥ III within 30 days of surgery

| CD 0–II, n = 342 | CD ≥ III n = 42 | Total, n = 384 | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.553 a | |||

| Median (range) | 66.5 (20.0–89.0) | 63.5 (42.0–84.0) | 66.0 (20.0–89.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 64.5 (11.9) | 63.5 (10.5) | 64.4 (11.7) | |

| Preoperative CA‐125 (units/ml) | 0.641 a | |||

| Median (range) | 482 (3–48 000) | 873 (45–32 000) | 523 (3–48 000) | |

| Mean (SD) | 1550 (3600) | 1940 (5020) | 1600 (3780) | |

| Missing, n (%) | 28 (8.2) | 2 (4.8) | 30 (7.8) | |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L) | 0.018 a , * | |||

| Median (range) | 36.0 (16.0–46.0) | 32.0 (20.0–44.0) | 35.0 (16.0–46.0) | |

| Mean (SD) | 34.1 (6.0) | 31.3 (6.3) | 33.8 (6.0) | |

| Subgroups, n (%) | 0.113 b | |||

| <30 | 69 (20.2) | 13 (31.0) | 82 (21.4) | |

| ≥30 | 218 (63.7) | 21 (50.0) | 239 (62.2) | |

| Missing | 55 (16.1) | 8 (19.0) | 63 (16.4) | |

| Preoperative BMI, n (%) | 0.258 c | |||

| <19 | 13 (3.8) | 2 (4.8) | 15 (3.9) | |

| 19–29 | 255 (74.6) | 27 (64.3) | 282 (73.4) | |

| ≥30 | 55 (16.1) | 10 (23.8) | 65 (16.9) | |

| Missing | 19 (5.6) | 3 (7.1) | 22 (5.7) | 1.000 c |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 31 (9.1) | 4 (9.5) | 35 (9.1) | |

| No | 293 (85.7) | 36 (85.7) | 329 (85.7) | |

| Missing | 18 (5.3) | 2 (4.8) | 20 (5.2) | |

| Preoperative WHO performance status, n (%) | 0.219 c | |||

| Grade 0 | 76 (22.2) | 10 (23.8) | 86 (22.4) | |

| Grade 1 | 213 (62.3) | 22 (52.4) | 235 (61.2) | |

| Grade 2 | 45 (13.2) | 8 (19.0) | 53 (13.8) | |

| Grade 3 | 6 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (1.8) | |

| Grade 4 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | 0.298 c | |||

| IIIA | 15 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 15 (3.9) | |

| IIIB | 7 (2.0) | 2 (4.8) | 9 (2.3) | |

| IIIC | 247 (72.2) | 28 (66.7) | 275 (71.6) | |

| VI | 72 (21.1) | 12 (28.6) | 85 (22.9) | |

| X | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Primary surgery, n (%) | 0.025 c , * | |||

| PDS | 265 (77.5) | 39 (92.9) | 304 (79.2) | |

| IDS | 77 (22.5) | 3 (7.1) | 80 (20.8) | |

| Complete cytoreduction at PDS or IDS, n (%) | 0.049 b , * | |||

| Yes (R0) | 173 (50.6) | 14 (33.3) | 187 (48.7) | |

| No (R >0) | 168 (49.1) | 28 (66.7) | 196 (51.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Surgical complexity score, n (%) | 0.014 b , * | |||

| Low (0–3) | 169 (49.4) | 11 (26.2) | 180 (46.9) | |

| Intermediate (4–7) | 121 (35.4) | 20 (47.6) | 141 (36.7) | |

| High (≥8) | 52 (15.2) | 11 (26.2) | 63 (16.4) | |

| Operating hospital, n (%) | 0.934 b | |||

| Tertiary hospital | 259 (75.7) | 31 (73.8) | 290 (75.5) | |

| County hospital | 83 (24.3) | 11 (26.2) | 94 (24.5) | |

| Completed 1st line chemotherapy, n (%) | 0.236 b , d | |||

| Yes | 308 (90.1) | 35 (83.3) | 343 (89.3) | |

| No | 26 (7.6) | 6 (14.3) | 32 (8.3) | |

| No chemo | 6 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (1.8) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| 90‐Day mortality, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.9) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (1.0) | |

| No | 339 (99.1) | 41 (97.6) | 380 (99.0) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | <0.001 a , * | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.70 (9.1) | 16.0 (10.5) | 9.50 (9.5) | |

| Median (range) | 8.00 (0–145) | 13 (2.0–52.0) | 8.00 (0–145) | |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CD, Clavien–Dindo; IDS, interval debulking surgery; PDS, primary debulking surgery; WHO, World Health Organization.

Tested by Welch's t‐test.

Tested by Chi‐square test.

Tested by Fisher's test.

Test excludes “No chemo.”

Statistically significant.

Preoperative albumin was significantly lower in the CD ≥ III cohort (median 32 g/L vs 36 g/L, P = 0.018). Significantly more women with severe complications had high SCS (≥8) (26.2% vs 15.2%, P = 0.014) and longer hospital stays (median 13 days vs 8 days, (P < 0.001). Complications CD ≥ III were significantly more common in women treated with PDS (P = 0.025) and significantly smaller number of women with complete cytoreduction had a severe complication compared with those with residual disease after surgery (P = 0.049), as shown in Table 4. There was no statistically significant difference in completed chemotherapy treatment between CD 0–II and CD ≥ III (91.1%, n = 308, vs 83.3%, n = 35, respectively, P = 0.236) (Table 4).

3.2. Regression analysis

Uni‐ and multivariable regression analyses with CD ≥ III as endpoint were performed (n = 384). Covariates were: preoperative albumin, timing of surgery (PDS or IDS), postoperative residual disease (R0 or R >0), and SCS (low, intermediate or high) (Table 5). The analyzed variables were selected as they were considered potential confounders when assessing the results of the statistical analysis between the cohorts (Table 4). Univariable regression analysis showed albumin, PDS, R0, and both intermediate and high SCS to be associated with severe complications (Table 5). The association between albumin and complications indicated a linear relation and for every increase per unit in albumin, the risk of severe complications decreased by a factor of 0.93. In the following multivariable analysis, only SCS was an independent risk factor for severe complications (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Uni‐ and multivariable logistic regression analysis of the complete cohort (n = 384) with complications CD ≥ III as endpoint

| Variables | CD ≥ III univariable regression analysis | CD ≥ III multivariable regression analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P‐value | OR (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| Preoperative albumin level (g/L) | ||||

| <30 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≥30 | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.012* | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.180 |

| Primary surgery | ||||

| IDS | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| PDS | 3.78 (1.32–15.92) | 0.030* | 4.70 (0.88–86.99) | 0.143 |

|

Complete cytoreduction at PDS or IDS |

1.0 |

1.0 | ||

| No (R >0) | ||||

| Yes (R0) | 0.49 (0.24–0.94) | 0.036* | 0.47 (0.20–1.04) | 0.068 |

| Surgical complexity score | ||||

| Low (0–3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Intermediate (4–7) | 2.54 (1.19–5.67) | 0.018* | 2.62 (1.05–7.21) | 0.047* |

| High (≥8) | 3.25 (1.32–8.02) | 0.010* | 4.11 (1.39–12.94) | 0.012* |

Abbreviations: CD, Clavien–Dindo; PDS, primary debulking surgery; IDS, interval debulking surgery.

Statistically significant.

3.3. Mortality and progression‐free survival

In the complete study cohort, four women died within 90 days. One died within 30 days and was registered as CD V (Table 3). The remaining three women did not have any registered complications greater than CD II.

The median PFS for the cohort of low SCS (n = 180) was 17.2 months (95% CI 15.2–20.7) compared with intermediate/high SCS (n = 204) of 21.5 months (95% CI 18.2–25.7); there was no significant difference when calculating the difference with 95% CI, although a statistical difference between the cohorts was found when log‐rank testing was performed (P = 0.038), as shown in Figure 1. For the PDS cohort, the median PFS was 21.4 months (95% CI 18.7–25.0) compared with 14.7 months (95% CI 12.7–18.3) for IDS; a significant difference was found with both 95% CI and log‐rank test (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) in all women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with primary debulking surgery or interval debulking surgery in 2013–2017, comparing low surgical complexity score (SCS) with intermediate/high SCS. The median PFS was 17.2 months (95% CI 15.2–20.7) in the low SCS cohort vs 21.5 months (95% CI 18.2–25.7) in the intermediate/high SCS cohort. Log‐rank test: P = 0.038

4. DISCUSSION

This study is one of the largest ovarian cancer cohorts and, to our knowledge, the first population‐based study cohort investigating surgical complications and their associations to patient characteristics and oncologic outcome. Our main findings are that SCS is an independent risk factor for severe complications and albumin is proposed to be a valuable predictor for severe complications. Furthermore, severe complications do not appear to affect completion of adjuvant chemotherapy significantly.

Surgical complications are associated with attempts towards complete cytoreduction and complex debulking surgery in advanced ovarian cancer in the effort to improve outcome. Notably, there is clear evidence that survival increases if complete cytoreduction is achieved at PDS or IDS 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 and studies evaluating complications and their associations should be considered important. Studying and analyzing complications are complex, as the women selected for advanced surgery have been clinically stratified according to risk and this causes a bias per se. The importance of individual preoperative risk assessment is emphasized in recently published guidelines by the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology. 10 We believe that covering a complete population is important to try to understand the risks of complications.

To be able to avoid severe complications it is important to understand which factors matter the most. Age is known as a major risk factor for complications, shown by Wright et al. in 2011 investigating ovarian cancer surgery; women <50 years old (n = 28 651) had a complication rate of 17.1% compared with 29.7% at age 70–79 and 31.5% at age ≥80. 11 This knowledge has most likely affected the way we assess patients preoperatively. In our study, we found a tendency for women in the CD ≥ III group to be younger than in the CD 0–II group. Interestingly, we found that complete cytoreduction does not increase the risk of complications, but residual disease does. One may consider our complete resection rate to be somewhat low, but our study represents a complete surgically treated population cohort. Moreover, a high tumor burden or a frail patient may be reasons for residual disease at surgery and may explain a higher risk of severe complications. The rate of severe complications differs in published studies, from 19.7% in a study by Fagotti et al. to 4.9% in a study by Di Donato et al. 28 , 29 The differences may depend on patient selection, surgical approach and how complications are reported and measured. According to previous studies, frailty is common in advanced ovarian cancer patients and results in a higher degree of severe complications and an affected survival. 18 , 30 Patients where a high frailty score was combined with an intermediate/high SCS were shown to have a higher risk of severe complications in a study by Di Donato et al.29 Inci et al. showed that frail patients had five times higher risk of complications. 30

In a study comparing women with residual disease 1–10 mm after PDS with women with R0 after IDS by Ghirardi et al., the rate of complications was 15%, which is similar to our rates. The women treated with PDS had a higher rate of both intraoperative complications (16.9% vs 1.3%) and postoperative complications (28.8% vs 2.0%) compared with those treated with IDS. Women treated with PDS were also younger and had a higher SCS. 9 Their results are confirmed by our findings that showed that PDS and a higher SCS resulted in more complications but, as expected, we found a significant difference in PFS between PDS and IDS, which has been shown in previous studies. 31 , 32 Furthermore, Aletti et al. have shown in a subgroup of 194 women with advanced ovarian cancer that a high SCS resulted in major complications in 63% of patients. 2 This subgroup was further analyzed and identified factors such as a high tumor burden or stage IV, ASA ≥ 3, albumin ≤30 g/L and age ≥ 75. Importantly, albumin is a known marker for nutritional status and was also significantly lower in our study cohort with severe complications.

Deciding which patient should receive which treatment is still a key issue. According to Swedish national guidelines, every patient with suspected advanced ovarian cancer is discussed at weekly regional multidisciplinary board meetings, which have decided on PDS, NACT or best supportive care since 2012. 33 In our region, the general recommendation has been to plan for PDS rather than NACT, even if the tumor burden is large. NACT is usually planned at age over 75 in combination with comorbidities, albumin <20 g/L or very affected general condition, but no formal algorithm is used. There have been no major changes in clinical praxis during the study period. The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center published an algorithm that triages patients with advanced ovarian cancer into high‐ or low‐risk surgery using radiologic assessment and selective laparoscopy. When the algorithm was used, 75% of the patients achieved complete cytoreduction and 94% optimal resection, defined as ≤1 cm residual disease. In the total population, 83% were treated with PDS and 17% with NACT, but in the high‐risk group, 51% received PDS and 49% NACT, with a complete cytoreduction rate of 54% and an optimal resection rate of 95%. 34 Our study differs somewhat, being a complete population‐based cohort, but we had a similar proportion of PDS (79%) and NACT (21%) and a complete total cytoreduction rate of 49%.

Another factor that may affect both complications and survival is the way healthcare is organized. We have previously shown a higher relative survival in advanced ovarian cancer after centralized primary treatment in a tertiary center with specialized surgeons. 35 , 36 Interestingly, Wright et al. have shown that high‐volume hospitals are associated with increased complication rates (24.6%) compared with low‐volume hospitals (20.4); however, the risk of death after a complication during the index hospital stay was significantly higher at the low‐volume hospital (8.0% vs 4.9%). 37 In comparison we found a very low 90‐day mortality rate of 1% (n = 4) and only one death within 30 days in our study that was performed after centralization in 2013–2017, which could be considered to be ensuring patient safety.

PFS was chosen as a survival measure in our study, instead of relative or overall survival, since the oncologic treatment of recurrence may have changed during the study period and could have affected the analyses and results of relative and overall survival. When comparing PFS between low vs intermediate/high SCS, which was the prognostic variable found predicting severe complications, we found no statistically significant difference in PFS with 95% CI, but when an additional log‐rank test was performed, there was a significant difference between the groups. A high SCS is most likely associated with a higher portion of complete cytoreduction and may affect PFS favorably.

One strength of our study is that it includes a complete population‐based cohort of advanced ovarian cancer treated with surgery, giving us the opportunity to map out severe complications and risk factors. Moreover, the high coverage and prospectively registered surgical outcomes together with a unique setting in a country with personal identification numbers enable valid follow‐up analyses. The generalizability of our study could be debated but may be considered adequate since it is a population‐based study where all patients undergoing surgery are represented. The limitations of our study are that some study variables possibly predicting complications were missing to some extent even in the medical records, which may have affected the results. The missing variables were, however, evenly distributed between the CD 0–II and CD ≥ III cohorts. Furthermore, we did not have full access to information on comorbidities that may affect the risk of complications, so we used the World Health Organization performance status as a surrogacy measure for frailty in an attempt to compensate for this. Complications are a noted quality indicator in the ESGO guidelines 10 and should be reported as side effects to advanced ovarian cancer surgery. Hopefully, future nationwide studies on complications will be able to address the important issue of the effect of complications on survival.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study shows that complex surgery in advanced ovarian cancer is associated with complications, although these complications do not seem tohave a significant effect on the completed adjuvant chemotherapy. Albumin <30 g/L, R >0, PDS, and both intermediate and high SCS was found to be associated with severe complications. Intermediate/high SCS was found to be an independent significant factor predicting severe complications and may affect PFS. The risk of complications should be taken into consideration when performing personalized treatment recommendations and forming algorithms. We hope to encourage further research on the possible impact of large cohorts of advanced ovarian cancer and surgical complications on survival.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

8. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Project development, data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing: CP. Data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing: HM. Data management, data analysis, manuscript editing: CS. Project development, manuscript editing: MJ and PA. Project development, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing: PD‐K.

9. ETHICS STATEMENT

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg approved the study, dates of approval February 26, 2015 and March 23, 2017 (Dnr 946–14, T283‐17). All included patients approved participation in the SQRGC.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank colleagues at Södra Älvsborgs Hospital in Borås, Norra Älvsborgs Hospital in Trolllhättan, Skaraborgs Hospital in Skövde, Hallands Hospital Varberg and Halmstad for their help with access to medical records and for reporting data of all women with ovarian, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal cancer to the SQRGC.

Palmqvist C, Michaëlsson H, Staf C, Johansson M, Albertsson P, Dahm‐Kähler P. Complications after advanced ovarian cancer surgery—A population‐based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:747–757. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14355

Funding information

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN2017/594, 190523, 19‐0524, 20 1346 PjF); Cancera Foundation; grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish Government and the county councils, the ALF‐agreement (ALFGBG‐813171/965702, ALFGBG‐435001, VGR 248481); the Swedish Research Council (2020‐02204); the King Gustav V Jubilee Clinic Research Foundation (2020: 333); and Hjalmar Svenssons Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Podratz KC, Cliby WA. Relationship among surgical complexity, short‐term morbidity, and overall survival in primary surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(676):e1‐e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aletti GD, Eisenhauer EL, Santillan A, et al. Identification of patient groups at highest risk from traditional approach to ovarian cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:23‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Narasimhulu DM, Thannickal A, Kumar A, et al. Appropriate triage allows aggressive primary debulking surgery with rates of morbidity and mortality comparable to interval surgery after chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:681‐687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hofstetter G, Concin N, Braicu I, et al. The time interval from surgery to start of chemotherapy significantly impacts prognosis in patients with advanced serous ovarian carcinoma ‐ analysis of patient data in the prospective OVCAD study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:15‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright AA, Bohlke K, Armstrong DK, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer: Society of Gynecologic Oncology and American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3460‐3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy vs primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open‐label, randomised, controlled, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kobal B, Noventa M, Cvjeticanin B, et al. Primary debulking surgery vs primary neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high grade advanced stage ovarian cancer: comparison of survivals. Radiol Oncol. 2018;52:307‐319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiofalo B, Bruni S, Certelli C, Sperduti I, Baiocco E, Vizza E. Primary debulking surgery vs. interval debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer: review of the literature and meta‐analysis. Minerva Med. 2019;110:330‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghirardi V, Moruzzi MC, Bizzarri N, et al. Minimal residual disease at primary debulking surgery vs complete tumor resection at interval debulking surgery in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a survival analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:209‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fotopoulou C, Planchamp F, Aytulu T, et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology guidelines for the peri‐operative management of advanced ovarian cancer patients undergoing debulking surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:1199‐1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright JD, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, et al. Defining the limits of radical cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:467‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smits A, Lopes A, Das N, et al. Surgical morbidity and clinical outcomes in ovarian cancer – the role of obesity. BJOG. 2016;123:300‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cham S, Chen L, St Clair CM, et al. Development and validation of a risk‐calculator for adverse perioperative outcomes for women with ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220(6):571.e1‐e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talbäck M. The completeness of the Swedish cancer register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:27‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chi DS, Zivanovic O, Levinson KL, et al. The incidence of major complications after the performance of extensive upper abdominal surgical procedures during primary cytoreduction of advanced ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:38‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patankar S, Burke WM, Hou JY, et al. Risk stratification and outcomes of women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:62‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumar A, Torres ML, Cliby WA, et al. Inflammatory and nutritional serum markers as predictors of peri‐operative morbidity and survival in ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3673‐3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar A, Langstraat CL, DeJong SR, et al. Functional not chronologic age: frailty index predicts outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147:104‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mutch DG, Prat J. 2014 FIGO staging for ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:401‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Regionala Cancer Centrum i Samverkan. Nationellt vårdprogram äggstockscancer. [Ovarian cancer‐ National care program.]. In Swedish. 2020;ed2020. https://cancercentrum.se/samverkan/cancerdiagnoser/gynekologi/aggstock/vardprogram/ [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484‐2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:928‐936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vergote I, Coens C, Nankivell M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs debulking surgery in advanced tubo‐ovarian cancers: pooled analysis of individual patient data from the EORTC 55971 and CHORUS trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1680‐1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade‐Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray‐Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO‐OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux pour les etudes des cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115:1234‐1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Gostout BS, et al. Aggressive surgical effort and improved survival in advanced‐stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:77‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta‐analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1248‐1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fagotti A, Ferrandina MG, Vizzielli G, et al. Randomized trial of primary debulking surgery vs neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (SCORPION‐NCT01461850). Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:1657‐1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di Donato V, Di Pinto A, Giannini A, et al. Modified fragility index and surgical complexity score are able to predict postoperative morbidity and mortality after cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:4‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inci MG, Anders L, Woopen H, et al. Frailty index for prediction of surgical outcome in ovarian cancer: results of a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:396‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dahm‐Kähler P, Holmberg E, Holtenman M, et al. Implementation of National Guidelines increased survival in advanced ovarian cancer ‐ a population‐based nationwide SweGCG study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161:244‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Angeles MA, Cabarrou B, Gil‐Moreno A, et al. Effect of tumor burden and radical surgery on survival difference between upfront, early interval or delayed cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2021;32:e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Regionala Cancer Centrum i samverkan. Äggstockscancer‐Nationellt vårdprogram. [Ovarian cancer‐ National care program.] In Swedish 2014.

- 34. Straubhar AM, Filippova OT, Cowan RA, et al. A multimodality triage algorithm to improve cytoreductive outcomes in patients undergoing primary debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer: a memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center team ovary initiative. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158:608‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palmqvist C, Staf C, Mateoiu C, Johansson M, Albertsson P, Dahm‐Kähler P. Increased disease‐free and relative survival in advanced ovarian cancer after centralized primary treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159:409‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dahm‐Kahler P, Palmqvist C, Staf C, Holmberg E, Johannesson L. Centralized primary care of advanced ovarian cancer improves complete cytoreduction and survival ‐ a population‐based cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Siddiq Z, et al. Failure to rescue as a source of variation in hospital mortality for ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3976‐3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]