Significance

Money has been seen as both the root of all evil as well as an agent of freedom. How it is put to use, however, depends very much on the recipient culture. Today, many small-scale societies that have led a subsistence-based lifestyle are experiencing the influx of money. Understanding the impact of cash is fundamental to confronting current issues, planning for the future, and realizing the many ways humans have found alternative paths to reshape societies and explore new options. A 44-year perspective on changes brought about by entrance into a partial cash economy indicates both very different strategies taken by households and growing material inequalities, along with the persistence of robust traditional social, political, and gender equalities.

Keywords: Kalahari hunter-gatherers, sharing, egalitarianism, impact of money, institutional change

Abstract

Money has been portrayed by major theorists as an agent of individualism, an instrument of freedom, a currency that removes personal values attached to things, and a generator of avarice. Regardless, the impact of money varies greatly with the cultural turf of the recipient societies. For traditional subsistence economies based on gifting and sharing, surplus perishable resources foraged from the environment carry low costs to the giver compared with the benefits to the receiver. With cash, costs to the giver are usually the same as benefits to the receiver, making sharing expensive and introducing new choices. Using quantitative data on possessions and expenditures collected over a 44-y period from 1974 to 2018 among the Ju/’hoansi (!Kung) in southern Africa, former hunter-gatherers, we look at how individuals spend monetary income, how a partial monetary economy alters traditional norms and institutions (egalitarianism, gifting, and sharing), and how institutions from the past steer change. Results show that gifting declines as cash is spent to increase the well-being of individual families and that gifting and sharing decrease and networks narrow. The sharing of meals and casual gifting hold fast. Substantial material inequalities develop, even between neighbors, but social, gender, and political equalities persist. A strong tradition for individual autonomy combined with monetary income allows individuals to spend their money as they choose, adapt to modern conditions, and pursue new options. However, new challenges are emerging to develop greater community cooperation and build substantial and sustainable economies in the face of such centrifugal forces.

When I receive a fine gift, I know that the giver, no matter how far away, holds me in her heart and will see me through hard times. (Tci!xo N!a, /Kae/kae village, Botswana, 1974)

Gifting and sharing in small-scale societies are considered be the oldest and most universal of economic activities. Reciprocal gifting is used to establish relationships (1), while sharing of resources and information, giving access to land, and lending emotional support provide the content of exchange partnerships as expressed in the above quote. Numerous motivations for such economic transfers in subsistence-based economies have been proposed where the social, emotional, and economic are entwined. These include helping close biological kin, dealing with unpredictable resources, building reputations, distributing indefensible perishable resources, extending social ties, and reproducing communities. The transfer of resources is governed by cultural institutions with their accompanying norms and values, which lower the transactional costs of exchange. The terms of sharing are generally that the one who has, gives to the one who is in need, provided that the need is real (2). Widespread sharing works when communities are small and intimate (3) and when the cost of sharing perishable resources to the giver is low relative to the benefit to the receiver, for example, the sharing of meat from a large game animal.

What happens then when money enters such economies? Marx (4) saw money as an agent of individualism that breaks down bonds between individuals based on kinship and other ascribed relations. Simmel (5) shared this view but also saw money as an instrument of freedom, challenging the moral order, distancing self from others and self from objects, and generating feelings of self-sufficiency and personal freedom. Yet, he also recognized the potential of money to create instability, disorientation, and despair by wrenching away the personal values attached to things and generating avarice and individualism. However, despite the universal and intrinsic power of money to transform cultural institutions and foster individualism, responses have been shown to vary greatly depending on the cultural and institutional turf of recipient societies (6–11).

When money enters an egalitarian forager economy, it accentuates individual interests and complicates decisions about gifting and sharing. As Graeber (12) put it, money introduces “a democratization of desire” (p. 190). Wild resources that are foraged by hunter-gatherers involve limited choices for dispensation, largely the question of to whom food or other items should be given. By contrast, money opens a broad range of choices and redefines former wants as needs; it can be spent to lessen workload, broaden diet, enhance lifestyle, seek status, expand social ties, or seek reproductive advantage. In a subsistence economy, the cost to the donor of giving cash is equal to the benefit to the receiver. Moreover, money can be concealed so that who is a “have” and who is a “have not” is not always easy to discern; it can also be spent on purchases that incur debt and turn the owner into a have not. What then is the impact of the introduction of money on a hunter-gatherer society and its institutions governing kinship obligations, support networks, risk pooling, and social cohesion? Here we address four questions among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen (!Kung), with quantitative data collected over a 44-y period from 1974 to 2018 (SI Appendix, section 1). (1) How do individuals choose to spend monetary income? (2) How does entrance into a partial monetary economy alter norms and institutions? (3) Conversely, how do existing institutions steer such change? (4) Do social inequalities develop in an egalitarian society with the introduction of cash, and if so, how?

Background

Ju/’hoansi and Forager Economic Institutions.

The lives of the Ju/’hoansi, who inhabit northeastern Namibia and northwestern Botswana, are described in outstanding ethnographies and films (13–20). In the past, the Ju/’hoansi were highly mobile foragers, exploiting more than 100 species of plant foods and 40 species of animals (14). Bantu moved into the area in the 1920s, adding meat and milk to the diet of those who worked for them (21). Since the late 1970s, the Ju/’hoan lifestyle has undergone substantial change as families have settled in permanent villages with a mixed economy composed of foraging, wage labor, sale of crafts, government relief food, old-age pensions, gardening, and animal husbandry (22). Two central institutions govern or have governed Ju/’hoan economic relations, as they do in many other hunting and gathering societies worldwide: gifting and sharing. Egalitarian norms provide the social matrix underlying and regulating Ju/’hoan economic institutions.

Gifting.

Reciprocal gift exchange creates and strengthens bonds in most human societies (1, 2, 23–27). Ju/’hoan gifts, whether beads, arrows, or clothing, are initially private property such that their transfer creates or underwrites a meaningful bond. The constant flow of gifts holds information about the status of an underlying relationship that provides mutual access to resources, sharing, and other forms of assistance (28, 29). Gifts are the tip of the iceberg overlying social relations (30). Reciprocation is usually delayed and not governed by time, quantity, or quality. Gifts travel widely; hoarding is heavy when possessions must be carried on one’s back (2).

Sharing.

Sharing differs from gifting in that it is often need based, addressing economic, social, and emotional shortfalls (29–34) and building cooperation in a community. The terms that the one who has gives to the one who is in need make it impossible to indebt others. With exceptions, in most hunting and gathering societies, food that comes in large packages is shared, while daily harvest is consumed at family hearths, as reflected in camp plans (35). Rules for sharing meat and other produce vary greatly from society to society (36); however, the Ju/’hoansi do have conventions that reduce the complexities of sharing and possibilities for conflict. Gathered foods and small game are consumed largely at extended family hearths. Meat from large kills is distributed first among the hunting party, who then give it out to their primary kin and affines, who in turn distribute their portions (16, 37). In the end, everybody gets a share. Sharing requires walking a thin line between generosity, which is valued, and giving too widely, which evokes complaints about spreading resources too thinly.

Sharing does not require direct reciprocation; more generalized reciprocation is hard to measure, because it occurs in different currencies over months or even years. Individuals realize that they may win in some relationships, lose in others, and break even in most (28, 37). Sharing has been proposed to serve a number of goals: to assist close biological kin ( 38–40), to deal with unpredictable conditions through risk pooling (28, 32, 33, 41–46), to enhance reputation (47, 48), to define and reproduce communities (3, 34, 49), to extend or restrict kinship obligations (29, 34), to serve as a leveling mechanism (50, 51).

Egalitarianism.

Egalitarianism is one of the most misunderstood forms of social organization. It is not based on sameness or lack of any differences in wealth but rather on individual autonomy and respect for the contributions of others. Fried (52) proposed that in an egalitarian society, there are as many positions in any age-set grade as there are individuals capable of filling them. Egalitarian communities are held together by the complementarity of individuals with different skills. Some men and women have influence to get certain things done but do not have power over others. Individuals seek status, but those who use it to dominate are leveled by others (53).

Individual autonomy is key to understanding egalitarian societies (54–57). As Ingold (58) noted, “the basic principle is that a person’s personal autonomy should never be reduced or compromised by his or her relationship with others” (p. 406). As a Ju/’hoan named Kasupe told Lee (15), “each one of us is a headman over himself” (p. 111) (this also applies to women). Individuals can move to another village if they feel that their autonomy is curtailed (59). Socialization for individual autonomy begins in a permissive and indulgent upbringing where children are rarely directed or punished (60, 61). Cooperative child rearing in small communities breeds affection, trust, and loyalty over decades, sentiments that can override individual interest (62, 63). Equality facilitates mobility, as hierarchies do not mesh easily (64); it reduces the transactional costs of exchange, because help received cannot be used to dominate or indebt another. Among the Ju/’hoansi, individual autonomy allows families to disperse following the husband’s or wife’s hxaro connections in times of social or environmental hardship. This is important, because few other Ju/’hoan villages could support large parties for longer stays. It encourages individuals to develop their own skills and allows people to stand up for themselves in the face of abuse or attempted dominance.

Hxaro.

Hxaro is a Ju/’hoan institution that combines gifting and sharing (28, 29, 65). The exchange of gifts signals the status of an underlying relationship involving access to sharing, alternate residences, and other forms of assistance from partners who “hold each other in their hearts.” Hxaro worked because there was sufficient variation in the population and environment of the region for effective risk pooling. Through hxaro exchange, both women and men stipulated for which kin, among many, they were responsible. Hxaro partnerships involved considerable long-term planning for storing in social relationships and anticipating delayed returns. Although initially established by close consanguineous ties, relatedness became diluted as ties were passed down across generations (29); trust was generated by a solid history of mutual support.

In 1974, both men and women maintained an average of 15 partnerships with consanguineous kin who lived between 2 and 200 km away, with the average person spending 4.4 mo a year away living with hxaro partners and 69% of possessions received as hxaro gifts (28). The Ju/’hoansi realized that over the long run, some partnerships would be very productive and others less so because of stochastic events. Unproductive relations may be maintained, “because useless people often have good children,” as one Ju/’hoan put it. Gifts traveled along chains of partners linking many, while stories kept relationships vivid over months or years apart (66). Many foragers mark mutually supportive relationships with gift exchanges, although hxaro may be more a more structured system than most because of the highly variable distribution of resources in the region.

Ju/’hoansi and Their Economies.

In this case study, 1974 data from four villages in /Kae/kae in Botswana are compared with those gathered in 2017 to 2018 in Nyae Nyae in Namibia by the same methods (SI Appendix, section 1). In 1974, the Ju/’hoansi in both Botswana and Namibia belonged to one ethnic group that crossed the border regularly; some 70% of hxaro partners of /Kae/kae residents lived in Namibia. The Ju/’hoansi at /Kae/kae supported themselves largely by hunting and gathering, although 15 families alternated between /Kae/kae and temporary jobs at Tsumkwe, the South African government’s settlement scheme in Namibia.

The Ju/’hoansi of Namibia have a very different recent history (22), although in the past, they were one population with the Ju/’hoansi of Botswana, sharing social institutions, hxaro partnerships, regular visits, seasonal gatherings, and circulation of stories (66) (map 2). In the 1970s, a Bushman homeland was established by the South African government in Namibia, later called Nyae Nyae. A brief history of Nyae Nyae from the 1970s until present is given in SI Appendix, section 1.

Today, the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae are settled in some 35 to 40 villages, with a population of approximately 3,000. Villages range from 20 to 90 residents, with larger ones being segmented into smaller clusters around a central water point. Mobility is still an important part of Ju/’hoan life, as people hitch rides on the many vehicles that circulate around Nyae Nyae to visit, shop, sell crafts, or seek job opportunities. Residential changes are frequent, as people alternate between husbands’ and wives’ villages or disgruntled groups of kin set up separate village segments. The Ju/’hoansi live in very different housing styles, with traditional grass or mud huts built next to self-built modern stone houses in the villages or very rudimentary run-down cement structures constructed at Tsumkwe.

Over two-thirds of Ju/’hoan traditional land was lost to the Kaudum game park in the north and repatriated Herero in the south (22), reducing hunting and gathering to some 15 to 30% of subsistence income (67). Today, the Ju/’hoansi cannot feed their families without cash income or government assistance (SI Appendix, section 1). Small-scale animal husbandry and gardening are practiced somewhat successfully in approximately 30% of villages. Some Ju/’hoansi, largely men, engage in casual labor for construction, professional hunting, or tourism. The few educated Ju/’hoansi with government jobs are paid high salaries with benefits. One source of income available to all for approximately 4 months a year is the harvest and sale of Devil’s Claw to pharmaceutical companies for the production of analgesics. Groups of families go to the bush for weeks or months of hard work, bringing with them purchased food; most people appreciate the opportunity to make money and the respite of living a more traditional foraging lifestyle.

The Namibian government has a number of programs that make life possible in this insecure economy. Old-age pensions of N$1,300 (approximately US$70 to 80) are paid out monthly from trucks furnished with ATMs that spit out the cash upon fingerprint recognition. Welfare payments are provided for children under 18 (N$250 per child), for patients receiving tuberculosis treatment, and for disability. Finally, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy (NNC) pays modest benefits to all conservancy members once a year. There are ample opportunities to spend cash earned at the many trade stores in the district capital of Tsumkwe. Although water is secure in Nyae Nyae, food insecurity is still seasonally high, and serious seasonal hunger continues (67). Traditional hunting has declined greatly, because the skills are not being acquired by youths.

Results

How Money Is Spent: Possession Inventory.

Numerous hypotheses can be derived from behavioral ecology for monetary expenditures: feed the family, save to cover risks, spend to ameliorate lifestyle, attract mates and sexual partners, expand social networks to gain influence and security, seek status through material possessions, strengthen community, or integrate with surrounding ethnic groups. We used two methods to see how money is applied to these different ends: (1) possession inventories for 1974 and 2018 (2017 to 2018) to document all material possessions of individuals and how they were acquired in order to understand how wealth, networks, and material inequalities have changed over time and (2) documentation of cash expenditures between 2020 and 2022 to capture the uses of money from the giver’s perspective, including cash gifted and money spent on food. The possession inventory was first carried out in 1974 among 51 women and men, 15 of whom were alternates between /Kae/kae and Tsumkwe for temporary employment. /Kae/kae was a very remote community at the time, with no nearby wage labor or stores. For each possession, age, sex, kin relation, and location of giver were recorded, in addition to names and attributes of hxaro partners. These lengthy interviews, in the Ju/’hoansi language, elicited a great deal of joking, laughter, and stories. For 2018, the same method was used. For both years, spouses could separate which household possessions they and their spouses had procured.

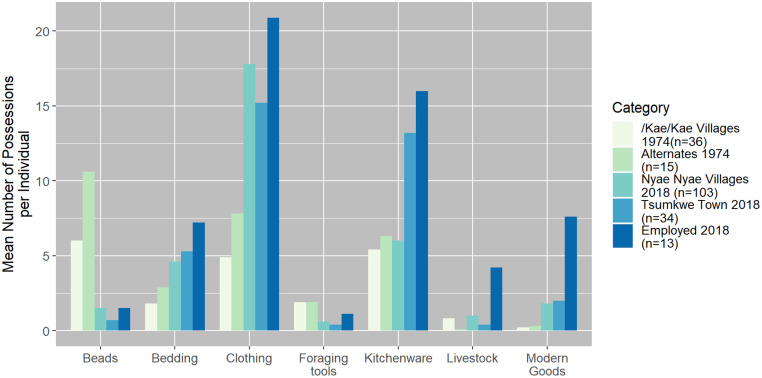

Fig. 1 sets the scene by showing assemblages of possessions in 1974 and 2018. A few trends are salient. The first is the high proportion of monetary income spent on goods providing domestic comfort in the harsh Kalahari climate: bedding, clothing, and kitchenware. The second is the decline in beadwork, an indicator of the waning of hxaro exchange and its far-flung networks. Decline in foraging tools and increases in livestock represent the switch to a mixed economy. Those with high salaries purchase modern goods to furnish their permanent houses in villages near Tsumkwe, including store-bought furniture, appliances, solar panels, metal roofing, smart phones, and used vehicles .

Fig. 1.

Material goods sought with increasing monetary income: 1974–2018.

The mean number of possessions rural villages was significantly higher in 2018 than in 1974 (t test, P < 0.00), but the difference was not as great as might be expected given increased cash income, access to stores, and greater sedentism (Table 1; full table in SI Appendix, section 4). This attests to the power of hxaro networks for moving goods in the past. Only when individuals became secured by high-paying regular jobs did the number of possessions greatly increase.

Table 1.

Mean number of possessions per individual by residence and year

| Category | 1974 ( per individual) | 2018 ( per individual) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /Kae/kae village | Alternates | Nyae Nyae village | Tsumkwe town | Employed | |

| Total | 21.1 | 29.9 | 33.4 | 37.2 | 58.6 |

| SD | 10.3 | 10.6 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 23.6 |

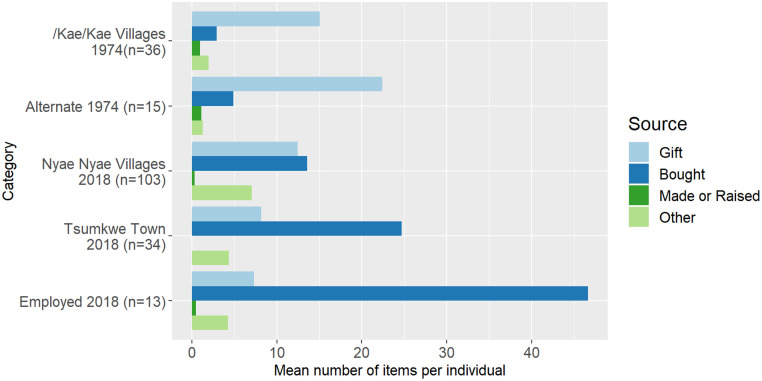

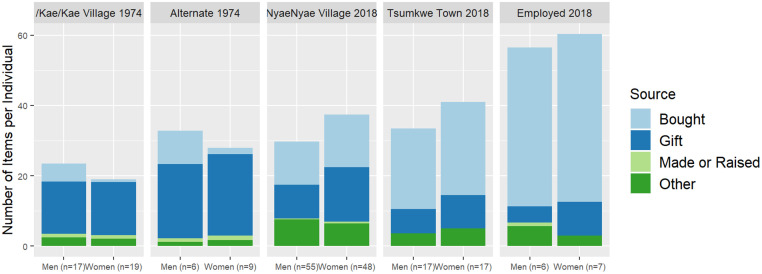

Fig. 2 gives the source of belongings by residence and year. Two differences stand out: the significant increase in purchases and decline in gifting as money becomes a more integral part of the economy. The few possessions purchased in 1974 at /Kae/kae were acquired via P.W. for sale of crafts. Alternates gifted a wide variety of purchased goods as an initial response to the jealousies caused by high cash income for the few who had temporary jobs in Namibia. This trend was to change.

Fig. 2.

Source of belongings by residence and year. Other includes non-Ju/’hoan nongovernmental organizations, tourists, and government.

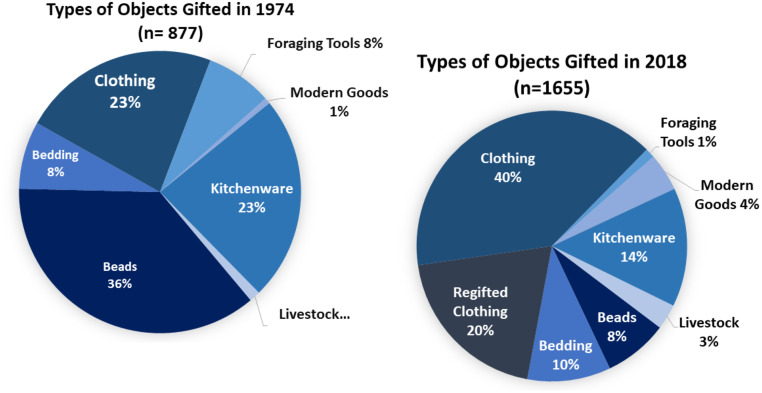

The types of goods gifted outside the household are shown in Fig. 3. The major items gifted in 1974 were highly valued beaded items that circulated widely in hxaro exchanges. Gifting of beads was relatively infrequent by 2018, although women still bought them for their own wardrobes. Cheap used clothes were by far the items most frequently given to friends and relatives in 2018. Most gifts were of lower value compared with those in 1974. Gifting of foraging tools declined in the mixed economy, while most modern store-bought goods were kept for self-use.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of types of possessions gifted by year.

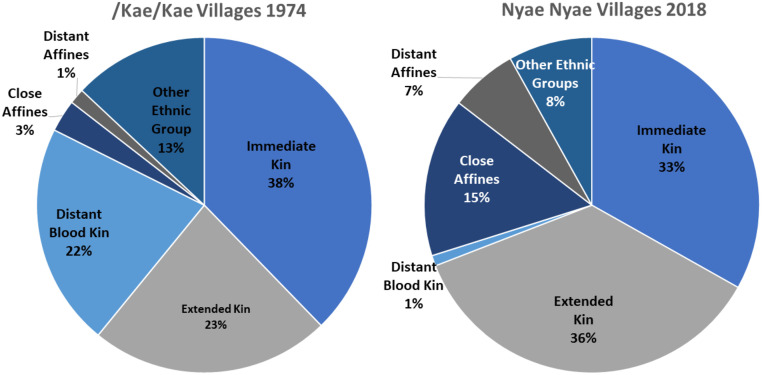

Hxaro secured ties with many partners who were not close kin and lived in distant areas in the past (28, 29). Do people use money to further expand their exchange networks for security or gain advantageous ties? Fig. 4 compares kin relations between receiver and giver between 1974 and 2018.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of kin ties between giver and receiver for 1974 and 2018 Close kin are parents, children, grandparents, and siblings. Other kin are more distant consanguineous kin.

For both years, rates of gifting with immediate kin, parents, adult children, and siblings were high. In 2018, a greater proportion of givers were extended kin: grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins (t test, P = 0.016). Hxaro was done indirectly with affinal kin in 1974, because people were said not to know the hearts of affinal kin well, but it was done directly with close affines in 2018, with increased spatial proximity. The greatest difference, however, was gifting with distant or nonkin, which dropped from 23% in 1974 to 1% in 2018 (t test, P < 0.00). It was not possible to compare spheres of exchange in kilometers between 1974 and 2018, because the border fence had blocked some movement between countries. Still, exchange networks clearly narrowed: in 1974, 187 (35%) of 538 gifts came from within the village, while by 2018, 608 (45%) of 1,337 gifts came from within (χ2 test, P < 0.00).

Documenting Expenditures.

To obtain a more comprehensive view of how money was spent from the giver’s perspective, we recorded spending for 188 Ju/’hoansi in the Nyae Nyae area soon after payday, including foodstuffs and the sharing of cash, which were not reflected in the possession inventory. The Ju/’hoansi feel that money, which is divisible and comes in fairly large quantities, falls under the practice of sharing. When gifts are desired, cash is used to purchase the appropriate material goods. This research was designed and monitored by P.W. and carried out by two highly experienced Ju/’hoan research assistants between 2020 and 2022. Expenditures were recorded soon after payday for 188 individuals. Most Ju/’hoansi gave detailed information for individual purchases and cash sharing, including location, age, gender, and relationship between giver and recipient.

Table 2 summarizes information on the various sources of cash in 2018 (SI Appendix, section 1). Table 3 addresses the question of whether the source of cash influences how it is spent.

Table 2.

Sources of cash

| Source of income | No. of individuals | Mean income per individual (N$) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casual | 9 | 942.2 | 503.5 |

| Devil’s Claw | 35 | 2,244.8 | 1,070.2 |

| Government salary | 38 | 3,562.8 | 1,395.7 |

| NNC benefits | 41 | 1,300.0 | 0.0 |

| Pension | 21 | 2,142.9 | 887.5 |

| Welfare | 44 | 888.2 | 509.5 |

US$1 = approximately N$14–15.

Table 3.

Mean individual cash expenditures by income source

| Source of income | No. of individuals interviewed | Shared | SD | Food | SD | Clothing | SD | Modern goods | SD | Debt | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casual | 9 | 194 (21) | 204 | 470 (50) | 203 | 222 (24) | 172 | 55 (6) | 167 | 11 (1) | 33 |

| Welfare | 44 | 104 (12) | 246 | 319 (36) | 190 | 192 (22) | 199 | 30 (3) | 104 | 184 (21) | 263 |

| NNC benefits | 41 | 157 (12) | 244 | 360 (28) | 204 | 153 (12) | 176 | 91 (7) | 175 | 515 (40) | 510 |

| Devil’s Claw | 35 | 559 (25) | 550 | 570 (25) | 499 | 170 (8) | 269 | 119 (5) | 268 | 479 (21) | 304 |

| Pension | 21 | 350 (16) | 363 | 463 (22) | 315 | 17 (1) | 53 | 81 (4) | 216 | 1,114 (52) | 1221 |

| Government salary | 38 | 242 (7) | 293 | 672 (19) | 431 | 196 (6) | 375 | 572 (16) | 1098 | 1,360 (38) | 899 |

Data are given as N$ (%).

The Ju/’hoansi earning casual income spend most of their cash to subsist but also maintain some sharing. Welfare also is largely applied to family needs. NNC benefits, where everybody gets the same payment at the same time, are used to purchase food and clothing and to repay debts. Pensioners accumulate significant debt, because stores extend credit to those with steady incomes; debt also shields them from requests beyond those of children and grandchildren. Money from Devil’s Claw harvest, the only income earned through cooperative efforts, has the highest percentage of income shared (t test, P < 0.000). Those on steady salaries with the highest income share a smaller percentage of their income than others (t test, P < 0.000) and incur large debts to buy expensive modern conveniences, including furniture, appliances, and sometimes used cars. This makes them have nots when asked to share. Source of income thus matters for spending. Finally, for a majority of Nyae Nyae Ju/hoansi, money has become a means to a greatly improve life conditions and is thus costly to share.

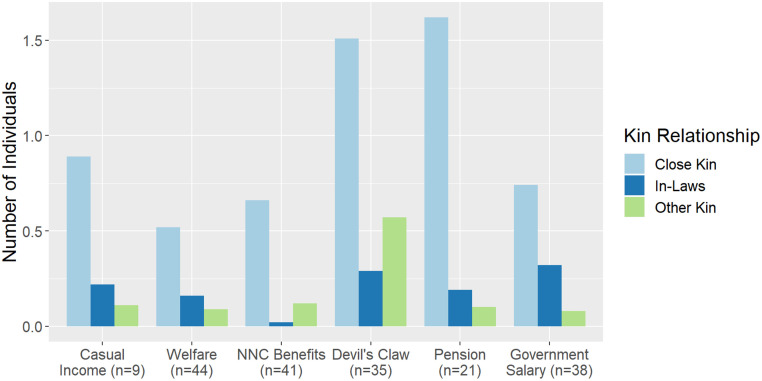

Fig. 5 identifies with whom cash is shared. Regardless of the source of cash, most sharing outside the household is with nuclear kin: parents, adult children and siblings, and grandparents. Only those who derived income from Devil’s Claw harvest shared with a significantly larger number of distant kin (t test, P = 0.003). Income from all sources was shared directly with nuclear affines, often families who provided alternate residences in nearby villages.

Fig. 5.

Kin relation of recipients of cash outside the household by source of income.

In summary, the possession and expenditure data indicate the following results. (1) Income earned from all sources is spent to purchase supplementary food for the family. (2) Money not spent on food is largely spent to ameliorate comfort and lifestyle. (3) Money is not generally spent to pursue status outside of owning a set of attractive clothing to wear on public occasions and a basic mobile phone. (4) Money is not used to attract more sexual partners (SI Appendix, section 1). Men and women with means do not divorce to seek new or more attractive spouses. (SI Appendix, section 1). (5) Money is spent by those with regular, high-salaried employment to enter the mainstream Namibian economy by building modern, store-furnished houses and purchasing used vehicles. (6) Money is not shared to extend networks.

Discussion

Impact of Money on Traditional Institutions of Giving and Sharing.

The most salient effect of the switch to a partial monetary economy is the decline in hxaro exchange. Research carried out in 1997 indicated that number of hxaro partners had already been reduced to half of 1974 levels (67). By 2018, few people knew anything about hxaro except from stories (66); gifting is still an integral part of relationships, although it is more spontaneous and casual than in the past. Why did networks decline so quickly? Formerly, when resources failed, families dispersed to live with other groups where they could hunt and gather to contribute to the food supply of the host camp. With semipermanent settlement, wild resources within range of a village are soon exhausted, so visitors can do little to contribute to the food supply of their hosts. People are more reluctant to welcome long-term visitors and share purchased food because of the many choices offered by cash (SI Appendix, section 1).

Some conventions around sharing are changing, while others remain the same. The major difference in food sharing comes from the reduction of large game hunting (SI Appendix, section 1). Meat from large game animals is still shared, following strong traditional norms in forager societies (68), but large kills are relatively rare. The meat sharing that tied together communities has been partially replaced by frequent and lively “tea and sugar parties,” open to most people present until teapots are emptied. Food cooked at extended family hearths may be shared with a few others, although the Ju/’hoansi tend to be circumspect about showing up at mealtime without reasonable grounds to do so. Unlike some hunter-gatherers today, the Ju/’hoansi do not have productive assets that can be shared, such as snowmobiles and motorboats (69). Seventeen salaried Ju/’hoansi in a population of 3,000, who live around Tsumkwe, own private vehicles. Owners do not lend vehicles but do give casual rides, with payment to help with fuel for longer trips. Phones may be loaned if the borrower pays for the units. Of course, radio programs, music, and the occasional video on a mobile phone may entertain many in the evenings.

What about cash that can come in large packages but offers so many possible choices? Obligations to very close kin are maintained; however, new conventions around sharing cash are developing, as ever more people have access to monetary income. These stipulate that individuals have full say over how to spend cash and only share once their own family’s needs and desires have been filled (SI Appendix, section 2). “When I get paid, I do get many requests. I tell my family and friends that first I will pay off my store debts and buy food, school uniforms, and other goods for the family and for myself. If no money is left, I tell them perhaps next time I can give them something. That is how I manage to have enough for myself but keep my friends.” This is reflected by the fact that for 67 (36%) of 188 payments recorded, participants reported deciding not to share with anybody in that round but to apply that payment to their own debts, needs, and wants. Five of 15 individuals mentioned that people did not share money because they liked what it could buy (SI Appendix, section 2).

New practices regarding the use of money circulate in conversations and stories around hearths where people tell of what others have bought, their own plans to earn money, and planned uses for money. Discussions often move into the arena of dreams for the future after darkness has fallen. Current attitudes toward the use of cash draw on two long-standing central principles of Ju/’hoan morality (70). One is that it is virtuous for both men and women to work hard to feed and care for their families. The other is that one should help a close circle of people to whom one has strong mutual obligations stemming from kinship ties and share something with others present when there is a surplus. Not surprisingly, the first has taken priority for cash expenditures in response to very real wants and needs, although the second was acknowledged in every statement. What has changed the most in this partial monetary economy is that former wants are now perceived as needs.

Money and Egalitarian Institutions.

Egalitarian institutions are one of the hallmarks of forager societies. As Simmel (5) suggested, money in Ju/’hoan society leads to greater personal freedom by wrenching away the personal values attached to things, but does money generate the individualism and avarice that underlie social inequalities? Money has created economic inequalities and a certain degree of acquisitiveness, but how far does this go toward breaking down other equalities? As can be seen in Fig. 6, gender inequality does not seem to have been eroded by money, even though 90% of the highest paying government jobs go to men. Women are ambitious and bring in monetary income through Devil’s Claw and crafts. There were no statistically significant differences between the number of possessions purchased by women and men from their own incomes for any year or place of residence. Women gifted significantly more than men in Nyae Nyae rural villages in 2018 only (t test, P < 0.00).

Fig. 6.

Source of possessions by gender and year.

Despite significant differences in wealth, respect and equality still hold. Ju/’hoansi in better equipped modern houses live side by side with those in traditional huts, with regular casual daily interactions and sharing of tea, tobacco, and occasional meals.

The Ju/’hoansi maintain autonomy and equality in a number of ways. They do not hire other Ju/’hoansi as household workers because of the lack of institutions to enforce accountability of workers or payment by employers. The Ju/’hoansi also do not put other Ju/’hoansi into debt, as do other populations in Namibia (71). Fewer than 6.7% of debts were to other Ju/’hoansi, because repayment to other Ju/’hoansi cannot be enforced. Leaders have long been respected within their own small kin groups. However, when the Ju/’hoansi move into positions of institutionalized authority in the NNC and decide on matters that affect all members, resentment brews (22). Kxao ≠Oma told Biesele (72) the following: “We never wanted to represent our communities. That was a White people’s idea in the first place.” There have been seven conservancy managers in the past two decades who have been voted out or quit after a variety of questionable accusations: drinking, damage to vehicles, misuse of funds, and incompetency. Others have resigned because of the inability to enforce accountability or control conservancy resources. Consequently, most managers have not been able to stay in the job long enough to gain valuable experience or knowledge, resulting in considerable costs to the Nyae Nyae conservancy.

Institutions shape the paths of innovations; institutional history matters. The changes brought about by money vary greatly between societies. In the 1970s, it seemed most unlikely that significant material inequalities would develop between those who lived side by side. At that time, the salaries of those who earned more and the goods purchased with them were widely circulated to assuage jealousies and conflicts triggered by the new wealth. However, some 40 y later, as money has settled into the economy, new conventions allow for substantial inequalities in material wealth to emerge without corresponding gender, social, or political inequalities. Why? One answer lies in the fact that the strong individual autonomy so characteristic of foraging societies is as important in a mixed economy for taking advantage of the many short-term opportunities that arise in tourism, crafts sale, casual labor, and development programs.

It is hard to know what the future will bring with low educational levels, a growing population, climate change, and land pressure from surrounding ethnic groups. There are some costs to reduced networks of gifting and sharing; however, there are also costs to maintaining broad networks and high mobility. The far-reaching networks of the past secured individuals and allowed them to move around and map onto natural resources, but they did not build stable communities that engaged in collective action. However, widespread cultural transmission is being reduced as networks narrow, such that some villages are gradually developing their own subsistence specializations and broader cooperation to fashion village cultures (SI Appendix, section 3).

With a touch of nostalgia for times past, most Ju/’hoansi feel they are better off today. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle that has been highly romanticized and popularized in the media was neither a Hobbesian nasty, brutish, and short lifestyle nor affluence without abundance (73) or paradise lost. Today, as in the past, life is still periodically very harsh and anxiety ridden. Individual autonomy has been carried forward from the past to provide a basis for new conventions that allow families to freely use money to improve their own food security and lifestyles. The challenge now is to develop greater community cooperation and collective action to produce more substantial and sustainable economies in the face of the centrifugal forces of autonomy coupled with the individualism bolstered by money.

Materials and Methods

P.W. conducted fieldwork at /Kae/kae in Botswana from 1973 to 1975 and in 1977. She interviewed 59 adults about their hxaro partners and asked men and women in the sample to bring out all of their possessions and provide information on source, including name of giver, age, sex, relationship, and residence for gifts.

P.W. returned to work with the Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae between 1996 and 2018 to track changes in population, subsistence, demography, and social networks (SI Appendix, section 1). From 2017 to 2018, P.W. repeated the possession inventory among 150 Ju/’hoansi from nine rural villages well distributed throughout the Nyae Nyae area and two scattered settlements in the town of Tsumkwe. These interviews were carried with P.W. and Ju/’hoan assistants camping in the villages and continuing discussions into the night. Information was collected on 5,465 possessions.

Between 2020 and 2022, two Ju/’hoansi, Fanie Tsemkxao and Kashe Tshao, who had worked with P.W. for 12+ years, collected data on how cash income was spent, detailing all expenditures from income earned on a recent payday for individuals at Tsumkwe and in nine other rural villages. P.W. monitored the study weekly by email and WhatsApp. The data were entered into Excel and analyzed by C.H.H. in R software (74). Figures were produced by C.H.H. using the Tidyverse package (75). The data used in all tables and figures are presented in SI Appendix, section 4.

The research was approved as exempt by the University of Utah (institutional review board 0992977). Because most participants were largely illiterate, the research was explained in the Ju/’hoan language and consent given verbally and by voluntary participation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many Ju/’hoansi in both Botswana and Namibia who helped us over the past 44 years, including the late Tomazho, Tshao ≠oma, Sebe Kxao, and N!hunkxa ≠oma, who taught P.W. how to ask questions and understand answers in the 1973 to 1977 work. For the more recent research, our collaborators /Aice N!aici, Tsemkxao/Ui, /Kaece Tshao, N!aici/Aice, /Kaece Tshao, and Charlie N!aici made invaluable contributions to the study. The NNC generously gave P.W. permission to carry out this work over the years.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2213214119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Some study data are available. (All data tables underlying figures, more complete summary statistics, and descriptions are given in SI Appendix, section 3, so that statistics can be checked. For anybody who wants to work with original data spreadsheets with data from individuals, please contact P.W., who then can get permission from the Ju/’hoansi for data sharing. That the data can be shared on the Internet is not included in institutional review board consent, as most participants are unfamiliar with the internet.

References

- 1.Mauss M., The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (Routledge, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahlins M., Stone Age Economics (Routledge, 1972). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird-David N., “Where have all the kin gone? On hunter-gatherers’ sharing, kinship and scale” in Towards a Broader View of Hunter-Gatherer Sharing, Lavi N., Friesem D., Eds. (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019), vol. N, pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx K., Capital (Penguin Random House, 1992), vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmel G., The Philosophy of Money (Routledge, 1978) pp. 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohannan P., The impact of money on an African subsistence economy. J. Econ. Hist. 19, 491–503 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyer J., Marginal Gains: Monetary Transactions in Atlantic Africa (University of Chicago Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurer B., The anthropology of money. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 35, 15–36 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parry J., Bloch M., Eds., Money and the Morality of Exchange (Cambridge University Press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchinson S., The cattle of money and the cattle of girls among the Nuer, 1930–83. Am. Ethnol. 19, 294–316 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shipton P., “Bitter money: Forbidden exchange in East Africa” in Perspectives on Africa: A Reader in Culture, History and Representation, Grinker R., Steiner C., Eds. (Blackwell, 1997), pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graeber D., Debt: The First Five Thousand Years (Melville House, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biesele M., Women Like Meat: The Folklore and Foraging Ideology of the Kalahari Ju/’hoan (Witwatersrand University Press, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee R., The! Kung San: Men, Women and Work in a Foraging Society (Cambridge University Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee R., The Dobe Ju/’hoansi (Wadsworth Thomson Learning, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall L., The! Kung of Nyae Nyae (Harvard University Press, 1976). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shostak M., Nisa: The Life and Words of a! Kung Woman (Harvard University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell N., Demography of the Dobe! Kung (Academic Press, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall J., The Hunters (film, Center for Documentary Educational Resources, 1956).

- 20.Marshall J., A Kalahari Family (film, Center for Documentary Educational Resources, 2007).

- 21.Wilmsen E., Land Filled with Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari (University of Chicago Press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biesele M., Hitchcock R., The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa (Berghahn Books, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lévi-Strauss C., The Elementary Structures of Kinship (Beacon Press, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godelier M., The Enigma of the Gift (University of Chicago Press, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komter A., Social Solidarity and the Gift (Cambridge University Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malinowski B., Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea [1922] (Routledge, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas N., Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Harvard University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiessner P., “Risk, reciprocity and social influences on! Kung San economics” in Politics and History in Band Societies, Leacock E., Lee R., Eds. (Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiessner P., “Kung San networks in a generational perspective” in The Past and Future of! Kung Ethnography, Biesele M., Gordon R., Lee R., Eds. (Helmut Buske Verlag, 1986), pp. 103–136. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas M., Isherwood B., The World of Goods (Routledge, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith D., et al. , A friend in need is a friend indeed: Need-based sharing, rather than cooperative assortment, predicts experimental resource transfers among Agta hunter-gatherers. Evol. Hum. Behav. 40, 82–89 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cronk L., et al. , “Managing risk through cooperation: Need-based transfers and risk pooling among the societies of the Human Generosity Project” in Global Perspectives on Long Term Community Resource Management, McGovern T., Cronk L., Lozny L., Eds. (Springer, 2019), pp. 41–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winterhalder B., Diet choice, risk, and food sharing in a stochastic environment. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 5, 369–392 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widlok T., “Extending and limiting selves: A processual theory of sharing” in Towards a Broader View of Hunter-Gatherer Sharing, Lavi N., Friesem D., Eds. (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019), pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.J. Yellen, Archaeological Approaches to the Present: Models for Reconstructing the Past (Academic Press, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiessner P., “Leveling the Hunter: Constraints on the status quest in foraging societies” in Food and the Status Quest, Wiessner P., Schiefenhövel W., Eds. (Berghahn Books, 1996), pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahuchet S., Food sharing among the pygmies of Central Africa. Afr. Study Monogr. 11, 27–53 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peterson N., Demand sharing: Reciprocity and the pressure for generosity among foragers. Am. Anthropol. 95, 860–874 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplan H., Gurven M., Hill K., Hurtado A. M., “The natural history of human food sharing and cooperation: A review and a new multi-individual approach to the negotiation of norms” in Moral Sentiments and Material Interests: The Foundations of Cooperation in Economic Life (2005), vol. 6, pp. 75–113. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly R., The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways (Smithsonian Inst. Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurven M., To give and to give not: The behavioral ecology of human food transfers. Behav. Brain Sci. 27, 543–559 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaplan H., Hill K., Food sharing among Ache foragers: Tests of explanatory hypotheses. Curr. Anthropol. 26, 223–246 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiessner P., Hxaro: A Regional System of Reciprocity for Reducing Risk among the! Kung San (University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, MI, 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cashdan E., Coping with risk: Reciprocity among the Basarwa of Northern Botswana. Man (Lond.) 20, 454–474 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gould R., “To have and have not: The ecology of sharing among hunter-gatherers” in Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers, Williams N., Hunn E., Eds. (Routledge, 2019), pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith E. A., “Risk and uncertainty in the ‘original affluent society’: Evolutionary ecology of resource-sharing and land tenure” in Hunter Gatherers. Vol. 1: History, Evolution and Social Change, Ingold T., Riches D., Woodburn J., Eds. (Routledge, 1988), pp. 222–251. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawkes K., Showing off: Tests of another hypothesis about men’s foraging goals. Ethol. Sociobiol. 12, 29–54 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkes K., Bliege Bird R., Showing off, handicap signaling and the evolution of men’s work. Evol. Anthropol. 11, 58–67 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myers F., “Burning the truck and holding the country: Property, time and negotiation of identity among the Pintupi Aborigines” in Hunters and Gatherers (vol 2): Property Power and Ideology, Ingold T., Riches D., Woodburn J., Eds. (Routledge, 1989), pp. 52–74. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodburn J., Egalitarian societies. Man (Lond.) 17, 431–451 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodburn J., “Sharing is not a form of exchange: An analysis of property-sharing in immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies” in Property Relations: Renewing the Anthropological Tradition, Hann C., Ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fried M., The Evolution of Political Society: An Essay in Political Anthropology (Random House; ) 1967), vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boehm C., Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior (Harvard University Press; ) 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leacock E., Women’s status in egalitarian society: Implications for social evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 19, 247–275 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gardner P., Foragers’ pursuit of individual autonomy. Curr. Anthropol. 32, 543–572 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gardner P., “Foragers with limited shared knowledge” in Towards a Broader View of Hunter-Gatherer Sharing, Lavi N., Friesem D., Eds. (McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019), pp. 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graeber D., Wengrow D., The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Penguin; ) 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ingold T., “On the social relations of the hunter-gatherer band” in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunter-Gatherers, Lee R., Daly R., Eds. (Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henriksen G., Hunters in the Barrens: The Naskapi on the Edge of the White Man’s World (Berghahn Books; ) 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Konner M., “Hunter-gatherer infancy and childhood in the context of human evolution” in Childhood: Origins, Evolution, and Implications, Meenhan C., Crittenden A., Eds. (University of New Mexico Press, 2016), pp. 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hewlett B., Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods: Evolutionary, Developmental, and Cultural Perspectives (Routledge, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hrdy S. B., Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origin of Mutual Understanding (Harvard University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hrdy S., Van Schaik C., Cooperative breeding and human cognitive evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues. 18, 175–186 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whallon R., Social networks and information: Non-“utilitarian” mobility among hunter-gatherers. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 25, 259–270 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiessner P., Hunting, healing and hxaro exchange: A long term perspective on! Kung (Ju/’hoansi) large-game hunting. Evol. Hum. Behav. 23, 1–30 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiessner P. W., Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14027–14035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiessner P., Owners of the future: Calories, cash and self-sufficiency in the Nyae Nyae area between 1996 and 2003. Vis. Anthropol. Rev. 19, 149–159 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lupo K., Schmitt D., How do meat scarcity and bushmeat commodification influence sharing and giving among forest foragers? A view from the Central African Republic. Hum. Ecol. 45, 627–641 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wensel G., “Sharing, money, and modern Inuit subsistence: Obligation and reciprocity at Clyde River, Nunavut” in The Social Economy of Sharing: Resource Allocation and Modern Hunter-Gatherers, Wenzel N. K., Hovelsrud-Broda G., Eds. (National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, 2000), pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Widlok T., Sharing by default? Outline of an anthropology of virtue. Anthropol. Theory 4, 53–70 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schnegg M., Becoming a debtor to eat: The Transformation of Food Sharing in Namibia. Ethnos Feb 17:1–21 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Biesele M., M. (2005). “Items of Ju/hoan belief and items of Ju/'hoan property” in Property and Equality: Ritualisation, Sharing, Egalitarianism, Widlok T., Tadesse W., Eds. (Berghahn Books, 2005), pp. 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suzman J., Affluence Without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 74.R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wickham H., et al. , Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Some study data are available. (All data tables underlying figures, more complete summary statistics, and descriptions are given in SI Appendix, section 3, so that statistics can be checked. For anybody who wants to work with original data spreadsheets with data from individuals, please contact P.W., who then can get permission from the Ju/’hoansi for data sharing. That the data can be shared on the Internet is not included in institutional review board consent, as most participants are unfamiliar with the internet.