Abstract

The diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) of metal ion (Mn+) during the repeated solid-to-liquid (StoL) plating and liquid-to-solid (LtoS) stripping processes intensifies fatal dendrite growth of the metallic anodes. Here, we report a new solid-to-solid (StoS) conversion electrochemistry to inhibit dendrites and improve the utilization ratio of metals. In this StoS strategy, reversible conversion reactions between sparingly soluble carbonates (Zn or Cu) and their corresponding metals have been identified at the electrode/electrolyte interface. Molecular dynamics simulations confirm the superiority of the StoS process with accelerated anion transport, which eliminates the DLA and dendrites in the conventional LtoS/StoL processes. As proof of concept, 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 exhibits a high zinc utilization of ca. 95.7% in the asymmetry cell and 91.3% in a 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 || Ni-based full cell with 80% capacity retention over 2000 cycles. Furthermore, the designed 1-Ah pouch cell device can operate stably with 500 cycles, delivering a satisfactory total energy density of 135 Wh kg−1.

A 91% zinc utilization is achieved via solid-to-solid metallic conversion electrochemistry.

INTRODUCTION

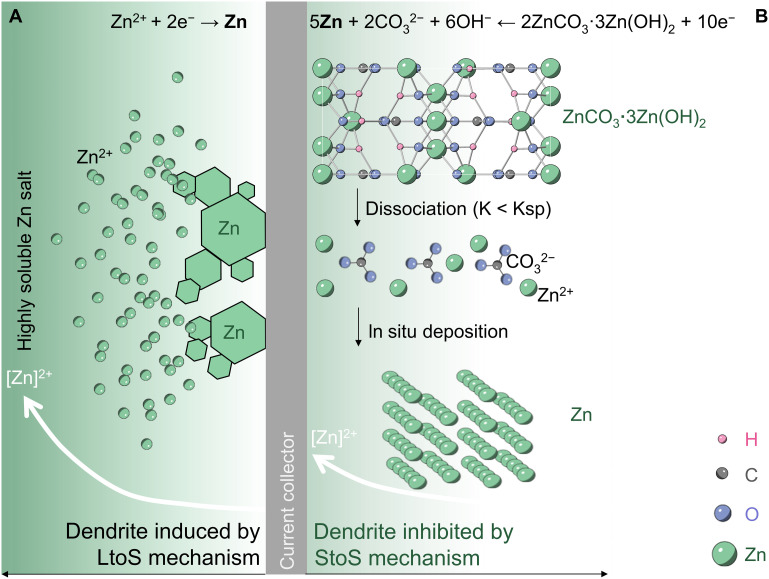

Metal-based (Zn, Cu, Fe, Al, etc.) rechargeable aqueous batteries have attracted extensive attention for a number of desirable characteristics such as high theoretical energy density, environmental friendliness, intrinsic safety, high abundance, and recyclability (1–5). Thereinto, Zn anode particularly features high theoretical capacity (820 mAh g−1 or 5855 mAh cm−3), low toxicity, and moderate working potential, i.e., −0.76 V versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), which is neither too high to degrade battery working voltage nor too low to trigger severe hydrogen evolution reaction (6). However, the Zn anode suffers from fatal dendrite growth, which is a complicated process and related to the electric/ion field, desolvation, nucleation, etc. Especially, for the liquid-to-solid (LtoS) electrochemical Zn deposition process [either Zn2+ in the neutral electrolyte or Zn(OH)42− in the strong alkaline electrolyte], the diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) intensifies the disordered fractals without apparent symmetry (see illustration in Fig. 1A), i.e., the notorious dendrite growth process (7, 8). Since the popularity of alkaline manganese-zinc primary batteries, tremendous efforts have been devoted to their secondary systems (9–11). Unfortunately, researchers have experienced arduous exploration, twists, and turns for decades, while the development is plagued by the high solubility of Zn(OH)42− in the strong alkaline electrolytes, which undergo DLA-triggered dendrite growth (10). Similarly, considerable efforts have also been pursued recently to suppress the dendrite growth in neutral electrolytes, such as additives in electrolyte (12–14), utilization of functional separator (15), adjustment on charging mode (16), selection of concentrated electrolytes (3, 17), construction of artificial solid-electrolyte interfaces (18–22) and three-dimensional porous Zn metal architectures (23, 24), and design of plating substrate (25). Although the issues are mitigated to some extent in the neutral electrolytes with specific solution environments or charge/discharge protocols, the DLA-oriented dendrite growth still cannot be exempted (6). Ultimately, the inevitable DLA that derived from the solid-to-liquid (StoL) Zn dissolution and LtoS Zn electrodeposition remains unsolved in either alkaline or neutral electrolyte. Attempts to convert the StoL and LtoS processes in the Zn metal battery might be promising to radically eliminate the dendrite problem.

Fig. 1. Schematics of charge storage mechanism at metallic Zn anodes.

(A) Traditional Zn metal anode with plating/stripping LtoS/StoL reaction process. (B) Sparingly soluble 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 anode with StoS reaction process.

Unfortunately, the oxidation products of the metallic anode are usually soluble, and Mn+ can diffuse easily from the surface of the electrode into the electrolyte, generating a concentration gradient. Inspiringly, two aqueous battery systems with metal-based anodes have been successfully commercialized without concerns about the dendrite growth, scilicet lead-acid battery and nickel-cadmium battery (11, 26). Concretely, for the lead-acid rechargeable batteries, during the discharge, Pb metal anode loses electrons to form Pb2+, and then Pb2+ reacts in situ with the available sulfuric acid on the electrode/electrolyte interface and nucleates to PbSO4 crystals (27, 28). Correspondingly, the dissociated Pb2+ from PbSO4 is converted to Pb in close proximity to the PbSO4 crystal during the charge process. As described above, the reaction mechanism of lead-acid battery is overall a solid-to-solid (StoS) conversion process instead of the StoL or LtoS process, and thus, the DLA effect is negligible (29). Note that the StoS process forming a sparingly soluble discharge product has a positive impact on receding the DLA effect, which is one of the initiators of dendrite formation and growth in aqueous metallic batteries. Therefore, it can be inferred that converting the conventional StoL/LtoS process to the StoS process is of great potential to eliminate the dendrite in metallic anode battery systems. As a consequence, the poor reversibility caused by the dendrite can also be solved, corporately enhancing the utilization of anode materials.

In this work, instead of relying on traditional StoL metallic anodes, we deploy sparingly soluble metal carbonates and a unique StoS conversion reaction to construct dendrite-exempt aqueous batteries. This new electrochemistry can suppress the DLA effect due to the preferred anion transport rather than the cation long-range diffusing between the electrode and electrolyte and renders long cycle stability. Specifically, during the discharge process, the sparingly soluble carbonate is in situ reduced to metal, while in the charging process the metal reacts with the available CO32− and OH− in the electrolyte and nucleates to form xMn/2CO3·yM(OH)n crystals adjoining the metal particles, instead of the Mn+ diffusion into the electrolyte causing concentration difference. Benefitting from this new design, the sparingly soluble carbonates, 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2, can be charged/discharged with 95.7% utilization and without dendrite growth for 3500 cycles. A full aqueous zinc-nickel battery constructed on the basis of this new anode design delivers a high zinc utilization of 91.3% and energy density of 270 Wh kg−1 (the total mass of both cathode and anode active materials) and long life span over 2000 cycles. Last, a commercial-grade 1-Ah prototype pouch cell presents an energy density of 135 Wh kg−1 and 90% capacity retention after 500 cycles based on this novel design. This work might open a new window toward ultrastable and safe aqueous batteries.

RESULTS

Mechanism of dendrite-exempt StoS zinc conversion electrochemistry

In selecting the new sparingly soluble Zn salts, the inorganic compounds are regarded as promising candidates because of their water stability compared with the organic Zn salts (30). Referring to the Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, the insoluble or slightly soluble inorganic salts like ZnCO3 and basic zinc carbonate could be potential candidates (31). ZnCO3 is soluble in strong alkaline solutions, slightly soluble under neutral conditions, and relatively stable in weak alkaline environments. When dissolving in a weak alkaline solution, ZnCO3 tends to precipitate into basic zinc carbonate. Fortunately, the basic zinc carbonate [with a chemical formula of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2] actually shows sparing solubility in neutral and weak alkaline solutions and structural stability without dehydration at room temperature (31). It seems reasonable to choose the sparingly soluble carbonates as active materials for stable anodes without the DLA effect.

It is worth noting that the molar volumes of the discharge and charge products of the anode are different in this system. Similar to a lead-acid battery, the volume change of the electrode may result in the shedding of active materials and ultimately lead to capacity decay. To fulfill this challenge, a graphene buffer is introduced as a composite electrode. The graphene not only provides nucleation sites in inhibiting the aggregation of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 during the chemical synthesis but also serves as a conductive buffer network in releasing the volume change during electrochemical charging/discharging (28, 32, 33). Therefore, 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2@graphene (ZZG) composite electrode was prepared designedly through a simple precipitation reaction. The structural characterizations of ZZG can be found in fig. S1 and note S1. As the basic carbonates are soluble in strong alkali (50 g in 1 M KOH), a weak alkaline K2CO3 aqueous solution (pH 12.27) was chosen to shape the slightly soluble environment in the performance evaluation. The existence of moderate CO32− and OH− in the solution would balance the kinetics of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 to Zn StoS reaction.

Inspired by the reaction mechanism of lead-acid battery and nickel-cadmium battery, we first speculate the detailed electrochemical processes of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 as follows: (i) During the electrochemical reduction process, the dissociated Zn2+ is deposited in the vicinity of the initial sites of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2. Then, the solubility product (Q = 0.042 g liter−1) of basic zinc carbonate is less than its solubility product constant (Ksp), and the rest of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 dissociates continually to replenish the consumed Zn2+ and balance the Ksp. (ii) During the oxidation process, the Zn metal loses electrons to Zn2+ and reacts with the available CO32− and OH−, forming 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 crystals. This StoS process keeps Zn anchored in situ to eliminate the DLA effect (as illustrated in Fig. 1B).

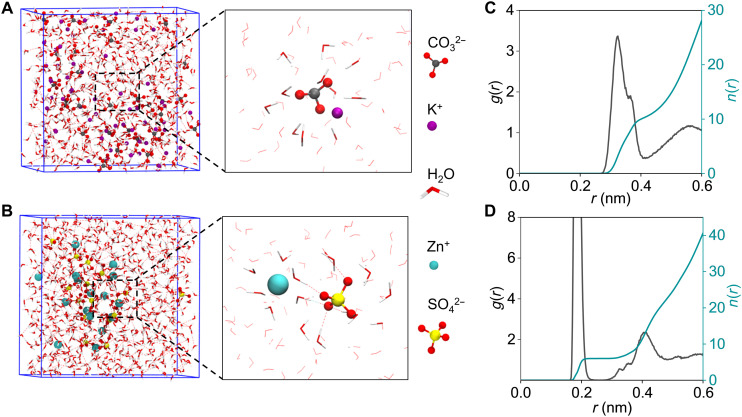

To certify the above supposition, molecular dynamics simulations and corresponding electrochemical tests were then carried out to analyze solvation and ion transport in the concerned K2CO3 electrolyte (Fig. 2A). On the basis of mean square displacement calculations, the calculated diffusion coefficient of CO32− and OH− anions in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte is 2.540 (±0.037) × 10−6 cm2 s−1 and 9.563 (±2.550) × 10−6 cm2 s−1, respectively, which are much higher than that of Zn2+ cation in 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte (Fig. 2B and figs. S2 and S3), i.e., 0.893 (±0.496) × 10−6 cm2 s−1. Namely, the proposed system would benefit from the fast anion transport of CO32− and OH− anions without the plague from the insufficient ion supply, which causes the DLA of Zn2+ during traditional LtoS Zn electrodeposition. Further analysis of molecular dynamics simulation results indicates that the first solvation shell of Zn2+ locates at around 2 Å with a coordination number of about six, while for CO32− the first peak of C─O (water) coordination appears at around 3.5 Å away from C, as demonstrated in Fig. 2 (C and D). The solvation shell of CO32− are about 10 water molecules, but it is not rigid compared with that of Zn2+, as indicated by the radial distribution functions. The hydrogen bonding of the surrounding water molecules and those coordinated with Zn2+ would slow down the diffusion of Zn2+. As a consequence, 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte delivers a high ionic conductivity (235 mS cm−1 at 25°C and 67 mS cm−1 at −20°C; see fig. S4) and a high CO32− transference number based on the Bruce-Vincent-Evans equation (see details in fig. S5), which should benefit the electrochemical performances.

Fig. 2. Molecular dynamics simulation of the local solvation environment.

Simulation box and the enlarged snapshots of (A) K2CO3 and (B) ZnSO4. (C) Radial distribution functions for the C atom of CO32−─O and (D) Zn2+─O collected from molecular dynamics simulations.

To further identify the relationship between ion transport and in situ StoS Zn conversion reaction, the potentiostatic measurement of the diffusion current i versus t−1/2 during the oxidation process is shown in fig. S6, based on the Randles-Sevcik equation (34)

| (1) |

where , A, F, n, and D are the surface concentration of Zn2+ species equilibrium with the metal, the area of the electrode (1 cm2), the Faraday constant, the apparent number of electrons transferred (2e−), and the diffusion coefficient of rate-limiting species, i.e., Zn2+ (0.893 × 10−6 cm2 s−1), respectively. The oxidation can be considered to be a reversible 2e− electrochemical process. The value is calculated to be about 1.6 × 10−4 M at −1.2 V versus SHE. As the solubility of basic zinc carbonate is about 0.042 g liter−1 (corresponding to 8.0 × 10−5 M) (30), the corresponding concentration of Zn2+ dissociated by the dissolved basic zinc carbonate should be 4.0 × 10−4 M [2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 ↔ 5Zn2+ + 2CO32− + 6OH−], which is higher than that of . Therefore, Zn2+ survives in the solution for a certain period of time before reacting with CO32− to form the basic zinc carbonate phase. This indicates that the electrochemical reduction of Zn2+ in K2CO3 solution proceeds under diffusion control. The reaction of Zn oxidation can continue through the diffusion of Zn2+ ions via the pore channels of the porous basic zinc carbonate. In addition, the diffusion coefficient difference between Zn2+ and CO32− suppresses the Zn2+ long-range diffusion from electrode to electrolyte during the traditional StoL Zn dissolution process. Similarly, the potentiostatic measurement of i versus t−1/2 during the reduction process is also tested, as shown in fig. S7 and note S2. It can be seen that most of the diffusion currents are generated by the diffusion of CO32−, which is consistent with the calculation results of a faster diffusion coefficient of CO32−. Due to the fast diffusion coefficient of CO32−, the diffusion of Zn2+ is very limited; therefore, the Zn2+ DLA from the electrolyte to electrode in the traditional LtoS Zn electrodeposition process can be inhibited. To better understand the process of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 ↔ 5Zn, a rotating disk electrode technique was used (see fig. S8 and relevant analyses in note S3), demonstrating diffusion-controlled processes for both the reduction of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 → 5Zn and the oxidation of 5Zn → 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2.

Electrochemical property of the StoS zinc conversion electrochemistry

The electrochemical performance of the sparingly soluble salt anode was investigated using a three-electrode test system, in which a piece of Zn metal sheet and a HgO/Hg electrode (0.095 V versus SHE) served as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. The cyclic voltammetric (CV) curves at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1 show a pair of redox peaks located at about −1.15 and −1.06 V versus SHE (fig. S9). The potential of −1.15 V should be ascribed to the reduction of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2, and that of −1.06 V corresponds to the oxidation of Zn metal. Figure 3A and fig. S10 show the typical galvanostatic profiles of the ZZG electrode at 0.5 C (1 C = 480 mA g−1). The charge/discharge plateaus can be easily discerned at the current density of 0.5 C, in accordance with the reduction/oxidation peaks of CV curves. The initial discharge capacity is about 510 mAh g−1 with an ultraflat plateau of ca. −1.15 V versus SHE. Here, the extra capacity should be ascribed to the side reactions, for example, the hydrogen evolution. The initial charge capacity is 465 mAh g−1 with an ultraflat plateau of ca. −1.05 V versus SHE, corresponding to a superior initial Coulombic efficiency of 91.2%. Here, the zinc utilization of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 is as high as 95.7% in the asymmetric cell, considering a theoretical specific capacity of 488.3 mAh g−1 based on 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 → 5Zn (see fig. S10 and calculations in note S4). To validate the effectiveness of the specific StoS mechanism in improving zinc utilization, the preliminary electrochemical performances with metallic Zn as the original active material were also investigated. Not surprisingly, the metallic Zn also delivers a reversible capacity of 734 mAh g−1 [based on the mass of Zn, 5Zn → 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2] and a high zinc utilization of 89.5%, considering a theoretical specific capacity of 819.8 mAh g−1 (fig. S11). We also observed that the ZZG can deliver high reversibility when coupling with the inert counter electrodes of Pt (fig. S12).

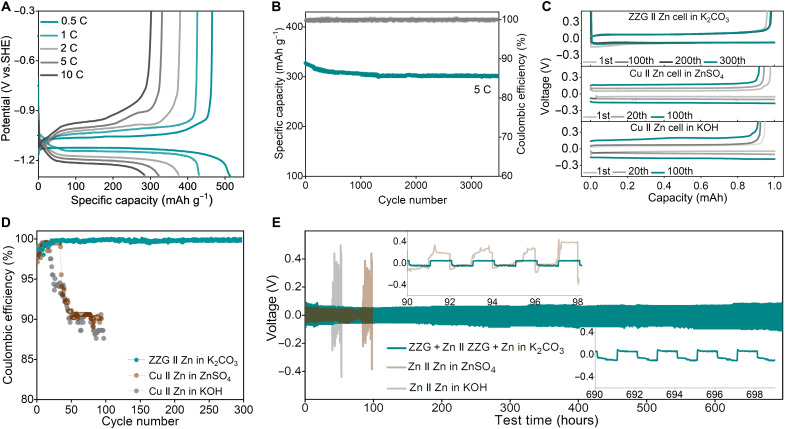

Fig. 3. Electrochemical characterizations of the sparingly soluble salt anode.

(A) Galvanostatic discharge-charge curves of the ZZG electrode in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte at different rates within −0.3 and −1.3 V versus SHE. (B) Long cycle stability of the ZZG anode in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte at 5 C within −0.3 and −1.3 V versus SHE. (C) Charge-discharge voltage gap of ZZG || Zn and Cu || Zn asymmetric cells in different electrolytes at different cycles with a current density of 1 mA cm−2 and a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. (D) Corresponding Coulombic efficiency for the cycling performance. (E) Long-term galvanostatic cycling performances of a symmetrical ZZG + Zn || ZZG + Zn cell in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte and Zn || Zn cell in 6 M KOH with a saturated ZnO electrolyte at 1 mA cm−2 with an areal capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. Insets are enlarged figures at different testing time.

Moreover, the discharge capacities of ZZG remain 432, 386, 328, and 281 mAh g−1 at current densities of 1, 2, 5, and 10 C, respectively, indicating a superb rate capability. The as-designed composite is capable of suffering 3500 full discharge/charge cycles at 5 C while sustaining high Coulombic efficiency near 100% and maintaining 80% capacity (Fig. 3B). The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (figs. S13 and S14) indicate the fast charge transfer and ion diffusion of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 nanoparticles and the ZZG, suggesting the kinetic contribution from both the nanosized structure and the conductive graphene substrate. The excellent solid-solid interfacial compatibility between 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 and Zn further contributes to the rate capability and reversibility of the phase change (fig. S15). To ensure the high Coulombic efficiency and long-term cycling stability, In2O3 and Bi2O3 powders were added to the electrode to suppress the concomitant hydrogen evolution reaction (figs. S16 and S17). In contrast, the capacity retention remains only 83% after 120 cycles without In2O3 and Bi2O3 addition (fig. S18).

The Zn reduction/oxidation Coulombic efficiency of ZZG in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte was investigated further using a ZZG || Zn asymmetric cell in Fig. 3C. In contrast, the Zn plating/stripping Coulombic efficiency of traditional Zn metal in 6 M KOH with saturated ZnO and 1 M ZnSO4 electrolytes was also investigated using Cu || Zn asymmetric cells with a current density of 1 mA cm−2 and an areal capacity of 1 mAh cm−2. Obviously, the ZZG || Zn cell shows a stable reduction plateau of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 → 5Zn (corresponding to Zn plating in traditional Zn metal anode Zn2+ → Zn) and an oxidation plateau of 5Zn → 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 (corresponding to Zn stripping in traditional Zn metal anode Zn → Zn2+). The capacity remains at 0.998 mAh after 300 cycles (Fig. 3C). However, the Zn plating/stripping overpotentials of Cu || Zn asymmetric cell in KOH and ZnSO4 electrolytes increase quickly, and corresponding stripping capacities decrease sharply. After the initial cycle, the Coulombic efficiency of the ZZG || Zn cell in K2CO3 electrolyte quickly increased to >99.0% within 10 cycles and finally stabilized at 99.8% after 50 cycles (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the Zn plating/stripping Coulombic efficiency of traditional Zn metal in KOH and ZnSO4 electrolytes quickly dropped after 20 cycles, which can be ascribed to the formation of Zn dendrite. The StoS Zn plating/stripping stability was also evaluated using a symmetric cell configuration in Fig. 3E. Note that ZZG symmetric cell is not workable because of the lack of an oxidation pair, so we applied ZZG + Zn || ZZG + Zn (ZZG and Zn powder mixed with a mass ratio of 1:1) for the demonstration. The Zn plating/stripping stability of traditional Zn metal in ZnSO4 and KOH electrolytes was also evaluated using Zn || Zn symmetric cells. The ZZG + Zn || ZZG + Zn symmetric cell cycling at an areal capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 shows high reversibility and stability over 700 hours, while the Zn || Zn symmetric cell collapses after only 60 hours in the KOH electrolyte and 100 hours in ZnSO4 electrolytes. When cycling at an areal capacity of 4 mAh cm−2, a stable operation within 200 hours can still be achieved, as shown in fig. S19. Furthermore, the symmetric cell based on half-reduced ZZG electrodes also shows high reversibility and stability over 400 hours (fig. S20). However, when cycled in 6 M KOH with a saturated ZnO electrolyte, an erratic voltage response with a rapid short circuit occurred after only 102 cycles (fig. S21). The results further reveal the effectiveness of the special StoS conversion mechanism in suppressing the dendrite growth.

In situ characterization of structural and morphological evolution

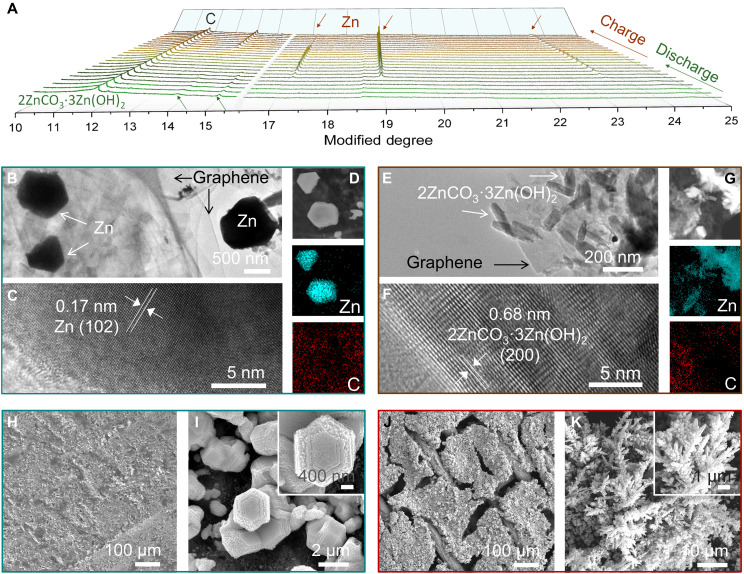

To elucidate the reaction mechanism of the ZZG anode, the structural and morphological evolution of ZZG electrodes during charge/discharge were investigated via ex situ and in situ synchrotron x-ray powder diffraction (XRD) measurements, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and in situ optical microscopy. According to in situ synchrotron XRD results (Fig. 4A), 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 is reduced to Zn metal during the discharge process, while the Zn metal is oxidized to form 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 crystals during the charge process, which can be clearly observed in a fully charged/discharged state (fig. S22). Specifically, there are almost no remaining diffraction peaks from 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2, suggesting that almost all 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 should be reduced to Zn. The reactions of the 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 electrode can be formulated as

| (2) |

Fig. 4. Morphologies of the ZZG anode after cycling in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte.

(A) In-situ synchrotron XRD patterns of the 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 anode during the discharge/charge process. (B to D) TEM and HRTEM images and energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) mapping of the ZZG electrode after discharge. (E to G) TEM and HRTEM images and EDX mapping of the ZZG electrode after charge. (H and I) Top-view SEM images of the ZZG electrode after 3500 cycles. (J and K) Top-view SEM images of the metallic Zn electrode after 50 cycles in 6 M KOH with a saturated ZnO electrolyte.

Accordingly, when 2 M K2CO3 aqueous electrolyte is adopted, the corresponding theoretical electrode potential of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 ↔ 5Zn would be −1.11 V, corresponding to the CV and galvanostatic charge/discharge curves.

Aside from the structural analysis by in situ XRD, the morphology changes of the ZZG electrode during cycles in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte were further monitored. At the fully discharged state, the reduced Zn particles are independently scattered on the graphene sheet substrate, exhibiting a hexagonal shape (Fig. 4, B to D, and fig. S23). After charging, the Zn particles are oxidized to 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 with uniform rice-like granules (about 100 nm) evenly distributed on the graphene sheet (Fig. 4, E to G), which is very similar to the pristine ZZG. After 100 cycles, the ZZG electrode exhibits dendrite-free characteristics without obvious aggregation (figs. S24 and S25), which remains as a porous feature without whiskers at the discharge state even after 3500 cycles (Fig. 4, H and I, and fig. S26A). Furthermore, in situ optical visualization observations of the ZZG electrode show the absence of protrusions at the edges or on the surface, except for a few small bubbles (fig. S27). In contrast, the Zn surface in 6 M KOH with a saturated ZnO electrolyte presents a porous structure with needle-like dendrites after 50 cycles (Fig. 4, J and K, and fig. S26B). This difference should be ascribed to the special StoS mechanism, which effectively suppresses the dendrite growth. In addition, the graphene serves as a conductive buffer network to accommodate the volume change of 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 particles during the electrochemical charging/discharge processes (figs. S25 and S28), which is beneficial to the cycle stability of the ZZG electrode.

To show the universality of the special StoS metallic conversion electrochemistry, we also evaluated the electrochemical performances of CuCO3·Cu(OH)2, which shares semblable physical and chemical peculiarities with 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2. CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene composite was prepared by a facile precipitation reaction. The XRD pattern (fig. S29) reveals the high purity of the formed monoclinic phase (Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards no. 02-0153). The as-prepared CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene electrode exhibits a high reversible capacity of ca. 474 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C, corresponding to high copper utilization of near 99% (fig. S30A). In addition, the capacity retention is as high as 95% after 1000 cycles (fig. S30B). Besides, the side-view SEM image demonstrates that the surface of CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene electrode is also free of dendrite growth after 1000 cycles (fig. S31). Thus, the StoS metallic conversion electrochemistry is proved to be adequate to avoid DLA influence, suppressing dendrite growth effectively compared with the StoL/LtoS electrochemistry.

The above analyses demonstrate that the sparingly soluble Zn or Cu carbonates can be reversibly charged/discharged, forming their representative metals. Specifically, in the reduction process, the sparingly soluble Zn or Cu carbonate crystals are in situ reduced to metal and release CO32− and OH− adjoining the electrode/electrolyte interface; vice versa, the metal oxidation processes are reversible. Hence, the DLA effect is evitable via the preferred anion transport rather than the cation of Zn2+/Cu2+ long-range diffusing between electrode and electrolyte. The StoS process has shown its superiority over the traditional LtoS process in getting rid of the DLA and dendrites, which should be of immediate interest and beneficial to the practical metrics of aqueous batteries.

Device evaluation based on StoS zinc conversion electrochemistry

Recently, attention has been attracted by the alkaline nickel-zinc battery for its impressive theoretical energy density, for example, 372 Wh kg−1 based on the charge state active material and 311 Wh kg−1 based on the discharge state active material (23, 35). The imposing electrochemical performance of the ZZG anode reported in this study makes the new generation of rechargeable zinc-based aqueous batteries possible. Here, Ni0.95Co0.03Zn0.02(OH)2 was applied in the cathode (fig. S32) (36). The first step is to optimize the electrolyte. It is found that the electrochemical performance of the cathode in pure 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte is worse than that in 1 M KOH electrolyte, including peak current, voltage hysteresis, and capacity (results are presented in fig. S33 and note S5). Hence, to activate the Ni-based cathode, a small amount of KOH was introduced into the K2CO3 electrolyte. The CV peak current density of cathode in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.01 M KOH electrolyte is higher than that in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte, but the CV curves cannot coincide well (fig. S34). Specifically, the peak current density increases to 9.5 A g−1 in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, and the CV curves remain similar from the first to the fifth cycle, suggesting that the Ni-based cathode can be fully activated. The discharge capacity in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte is about 248 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C after the initial charge/discharge cycle and remains about 175 mAh g−1 at 10 C (fig. S34, C and D). It is found that after activation in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH, the Ni0.95Co0.3Zn0.2(OH)2 cathode can also exhibit high specific capacity and good cycling stability in 2 M K2CO3 electrolyte (fig. S34, E and F). The electrochemical characteristic of the ZZG composite was also measured with different KOH addition. In 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte, the CV curves of ZZG in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte almost overlap during 2 to 5 cycles, and the capacity retention of ZZG || Zn asymmetric cell is 0.997 mAh after 50 cycles, suggesting its high reversibility (fig. S35). In comparison, the peak intensity of ZZG decreases in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.2 M KOH electrolyte, which is supposed to be related to the solubility change of ZZG in such electrolytes with more alkaline (fig. S36). Therefore, 0.1 M KOH addition is considered optimal for a full-cell evaluation by considering both the activity of Ni-based cathode and the reversibility of the ZZG anode.

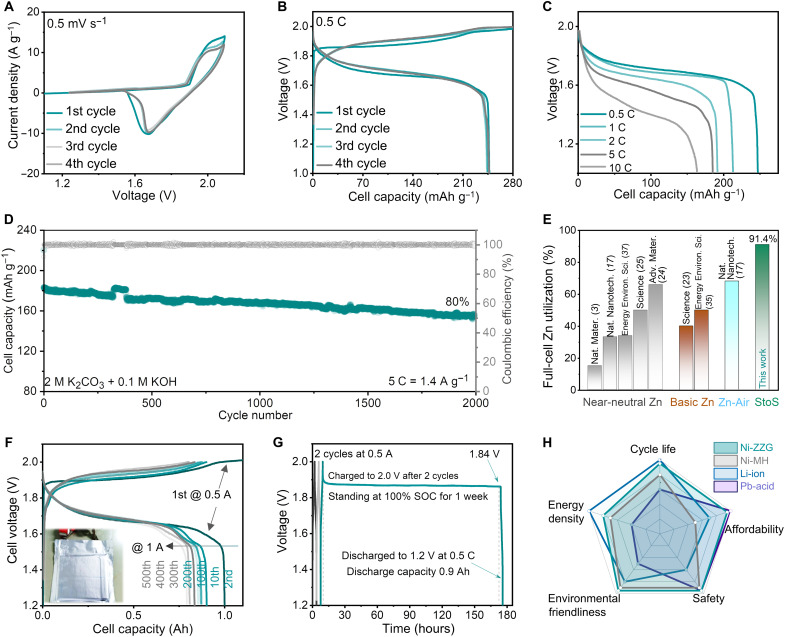

On the basis of the above optimization, a full cell with Ni-based cathode, ZZG anode, and 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte can be constructed using compact Swagelok-type batteries (named Ni-ZZG battery). The possible practical reaction processes of the full cell are preliminarily discussed in note S5. Considering the specific capacity of cathode and anode, the mass ratio between Ni-based cathode and ZZG anode was set as 1.8:1 with a cathode active material mass load of 70 mg cm−2, in which the anode capacity exceeds 5% that of the cathode to prevent the hydrogen evolution reaction. The CV curves of the full cell show that an anodic peak and a cathodic peak were located at 1.90 and 1.69 V under a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1, respectively (Fig. 5A). The redox process is highly reversible, as evidenced by the overlapped CV curves and charge/discharge curves after the first cycle. As depicted in Fig. 5B, the battery can obtain a well-retained discharge capacity of 248 mAh g−1. Furthermore, the Ni-ZZG battery shows a superb rate capability, achieving high average discharge capacities of 220, 190, 185, and 170 mAh g−1 at 1, 2, 5, and 10 C, respectively (Fig. 5C). The battery exhibits good low-temperature and overcharge performances (fig. S37). In comparison with the Pb-acid and Ni-Cd metal-based batteries, there is no obvious memory effect in the StoS conversion electrochemistry, suggesting its wider application prospect (fig. S38). The full cell also exhibits imposing long cycle stability, with high capacity retention of 80% after 2000 cycles at 5 C (Fig. 5D). The cycling stability of the full cell should benefit from the high reversibility of the ZZG anode as evidenced above.

Fig. 5. Electrochemical performances of the Ni-ZZG full cell in 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH electrolyte and 1-Ah pouch cell.

(A) CV curves of the full cell at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1 between 1.1 and 2.1 V. (B) Galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of the full cell (the battery was fully charged at 0.5 C for 2 hours and then discharged to 1.0 V at 0.5 C). (C) Rate capability of the full cell (the battery was fully charged at 0.5 C for 2 hours and then discharged at different rates to 1.0 V). (D) Long cycle stability of the full cell at 5 C within 1.0 and 2.0 V. (E) Zinc utilization of different Zn-based devices in a scale of full cells. (F) Galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of the pouch cell (the battery was first fully charged at 0.5 C for 2 hours and then discharged to 1.2 V at 0.5 C to be fully activated). (G) Charge retention capacity of a full cell evaluated by resting for 1 week at 100% state of charge after two cycles at 0.5 A, followed by full discharge. (H) State-of-the-art comparison of different batteries.

In addition, zinc utilization in the full cell is calculated to be as high as 91.3%, which is among the highest values compared with those of the reported values (see Fig. 5E, table S2, and calculations in note S4) (3, 17, 23–25, 35, 37). Note that most of the previous work applied impractical full-cell components using excess Zn to prevent its premature depletion. Here, we take the metrics of zinc utilization on a scale of a full cell. Owing to the high zinc utilization, an energy density of more than 270 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 152 W kg−1 can be achieved on the basis of the mass of both cathode and anode active materials (see calculation method in note S6). Benefitting from the lean-electrolyte design, the energy density of the full cell is as high as 164 Wh kg−1, based on the mass of electrolyte and active materials. The values outperform those of the reported Zn batteries and most of the developed aqueous batteries (table S3), such as Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O || Zn (150 Wh kg−1 at 60 W kg−1) (2), Li2Mn2O4 || Zn (180 Wh kg−1 at 43 W kg−1) (3), VOPO4 || Zn (100 Wh kg−1 at 95 W kg−1) (17), Zn2(OH)VO4 || Zn (140 Wh kg−1 at 70 W kg−1) (24), β-MnO2 || Zn(254 Wh kg−1 at 197 W kg−1) (38), LiMn2O4 || Mo6S8 (100 Wh kg−1 at 45 W kg−1) (39), LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 || Li4Ti5O12 (165 Wh kg−1 at 82 W kg−1) (40), LiCoO2 || Mo6S8 (80 Wh kg−1 at 150 W kg−1) (41), and LiCoO2 || Li4Ti5O12 (130 Wh kg−1 at 150 W kg−1) (42). For a universality exploration, a full cell based on CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene anode and Ni0.95Co0.03Zn0.02(OH)2 cathode was also demonstrated. The mass ratio between the cathode and anode was set to 1.9:1.0. Such a cell delivers a highly reversible capacity of nearly 246 mAh g−1 with two discharge plateaus at 0.90 and 0.55 V (fig. S39). The full cell also exhibits a high copper utilization rate near 98% and capacity retention of 92.0% after 1000 cycles at 5 C. Apparently, the StoS metal conversion electrochemistry enables a full cell with excellent cycle life, high efficiency, and unprecedented metallic anode utilization.

To verify the device feasibility, a pouch-type Ni-ZZG device was also fabricated in ambient air condition. The battery delivers a capacity of 1 Ah at a charge/discharge current of 0.5 A, which corresponds to a high energy density of 135 Wh kg−1 (Fig. 5F). After 500 cycles at a charge/discharge current of 1 A, the battery exhibits 90% capacity retention. As known, self-discharge is severe for traditional Ni-Zn batteries because the by-product of self-discharge is soluble in its strong basic electrolyte, which results in continuous self-discharge (23). The Ni-ZZG battery, however, exhibits an acceptable self-discharge with 90% capacity retention after a rest for 1 week (Fig. 5F). The low self-discharge of Ni-ZZG full cell is a prerequisite for its practical application. Last, the practical metrics of the Ni-ZZG battery, including the cycle life, energy density, environmental friendliness, safety, and affordability, were evaluated in comparison with other commercial battery systems (Fig. 5H). It can be concluded that the Ni-ZZG battery might be a promising alternative to these battery systems on some occasions, considering the advantages of intrinsic safety, low cost, nontoxicity, and electrochemical stability.

DISCUSSION

We have adopted the sparingly soluble salts as an anode active material in the weak alkaline electrolyte, which is proven effective in eliminating the detrimental metal dendrite growth and improving significantly the utilization ratio, which has been a common challenge for aqueous metal-based batteries. The novel StoS conversion reaction mechanism eliminates the limits due to metal cation diffusions in conventional LtoS reactions. Benefiting from that, 2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 and CuCO3·Cu(OH)2 can exhibit long cycle life without Zn or Cu dendrite growth. When coupled with Ni-based cathode, the Ni-ZZG battery full cell exhibits a high zinc utilization of more than 91%, prolonged life span of more than 2000 cycles, and a superior energy density of 270 Wh kg−1. Such a StoS conversion electrochemistry may provide a new path to solve the utilization and dendrite problems of metallic anodes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

2ZnCO3·3Zn(OH)2 and graphene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. ZZG was thus prepared by a precipitation reaction: 50 mg of graphene was dispersed in 50 ml of distilled water by ultrasonic treatment. Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (5.95 g) was dissolved. Then, 1 M K2CO3 solution was dropped into the above solution at a feeding speed of 1 ml min−1 until the pH reached 6.5. The whole process was operated under vigorous magnetic stirring. Afterward, the precipitated powders were collected by filtration and washed with distilled water and ethanol. Last, the powders were dried at 60°C overnight to obtain the product of ZZG. The content of graphene in the ZZG composition is about 2 weight % (wt %).

CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene composite was prepared by a precipitation reaction. Graphene (50 mg) was dispersed in 50 ml of distilled water by ultrasonic. Then, 2 g of CuSO4·5H2O was dissolved. KHCO3 solution (1 M) was dropped in the above solution at a feeding speed of 1 ml min−1 under magnetic stirring until the pH reached 8.5. The precipitated powders were collected by filtration and washed with distilled water and ethanol. Last, the powders were dried at 60°C overnight to obtain the product of CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene. The content of graphene in the CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene composition is also about 2 wt %.

Ni0.95Co0.3Zn0.2(OH)2 was prepared by a coprecipitation reaction. Briefly, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in distilled water with a molar ratio of Ni:Co:Zn = 95:3:2, and the concentration of the solution is 1 M. The mixed solution was put into a long-neck round-bottom flask. Simultaneously, 1 M solution of KOH was pumped into the flask until the pH reached 8.5 at a feeding speed of 1 ml min−1 under magnetic stirring. The reaction was conducted at 50°C and maintained for one night. Then, the coprecipitated powders were collected by filtration and washed with distilled water and ethanol. Last, the powders were dried at 60°C overnight.

Material characterizations

XRD patterns were obtained on Bruker Smart 1000 (Bruker AXS Inc.) using Cu Kα radiation with an airtight holder from Bruker. The morphology of the sample and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping were investigated by field-emission SEM (Oxford Instruments X-Max Extreme). TEM, high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), and EDS mapping were performed on a JEOL ARM200CF microscope at 200 kV. All of the samples for ex situ SEM, TEM, and XRD were recovered from aqueous Swagelok-type cells after electrochemical cycles. The operando in situ synchrotron XRD was recorded in the powder diffraction beamline of the Australian Synchrotron with a beamline wavelength (λ) of 0.6885 Å in transmission mode. An in-house–designed cell was used for the data collection with x-ray transparent windows by Kapton film.

Electrochemical measurements

The ZZG electrodes were prepared by mixing 85% active materials powder, 5% graphite, 4% carbon black, 1% In2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), 1% Bi2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), and 4% polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) in Milli-Q water. The slurry mixture was then coated on a brass screen (150 mesh, area mass of 15 mg cm−2) and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene electrodes were prepared by mixing 85% active materials powder, 5% graphite, 5% carbon black, and 5% PTFE in water. The slurry mixture was then coated on a stainless steel screen (150 mesh, area mass of 20 mg cm−2) and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. Then, all anode electrodes were compressed under a pressure of 0.1 MPa to guarantee good contact between active materials and conductive additives. The typical mass loading was about 40 mg cm−2. Ni0.95Co0.3Zn0.2(OH)2 was prepared by mixing 85% active materials powder, 5% graphite, 5% carbon black, and 5% PTFE in water. The slurry mixture was then cast into nickel foam (with a thickness of 2 mm and area mass of 30 mg cm−2) and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. Then, all cathode electrodes were compressed under a pressure of 5 MPa. The typical mass loading is about 70 mg cm−2. Glass fiber was used as a separator (with a thickness of 1 mm). The amount of electrolyte was controlled under a lean-liquid level of about 60 μl in volume in the Ni-ZZG full batteries.

The ZZG || Zn asymmetric cell was assembled with ZZG electrode and Zn powder electrode. The Zn powder electrode was prepared by mixing 85% Zn powder, 5% graphite, 4% carbon black, 1% In2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), 1% Bi2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), and 4% PTFE in Milli-Q water. The slurry mixture was then coated on a brass screen (150 mesh, area mass of 15 mg cm−2) and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. The Cu || Zn asymmetric cell was assembled with Cu foil as the working electrode and Zn powder as the counter electrode. The ZZG + Zn || ZZG + Zn symmetric cell was assembled with ZZG + Zn electrode. The ZZG + Zn electrode was prepared by mixing 47.5% Zn powder, 47.5% ZZG powder, 5% graphite, 4% carbon black, 1% In2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), 1% Bi2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), and 4% PTFE in water. The slurry mixture was then coated on a brass screen (150 mesh, area mass of 15 mg cm−2) and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. The Zn || Zn symmetric cell was assembled with Zn powder electrode.

CV was carried out using a CHI 600E electrochemical workstation. The electrochemical performances of CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene were investigated using a three-electrode test system between 0.1 and −0.6 V versus SHE, in which a Pt sheet and a HgO/Hg electrode served as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. The volume of electrolyte in the three-electrode tests is about 5 ml. The charge-discharge experiments were performed on a Land BT2000 battery test system (Wuhan) at room temperature. The galvanostatic charge/discharge of the ZZG anode was carried out between −0.3 and −1.3 V versus SHE. The galvanostatic charge/discharge of CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene anode was carried out between 0.1 and −0.6 V versus SHE. For the cathode rate performances, the half cells were first fully charged at 0.5 C (1 C = 280 mA g−1) and then discharged to a cutoff potential of 0.3 V versus SHE, at different current densities from 0.5 to 10 C. Before the full battery was assembled, the cathode was first fully charged at 0.5 C (1 C = 280 mA g−1) and then discharged to a cutoff potential of 0.3 V versus SHE to fully activate Ni0.95Co0.3Zn0.2(OH)2. For the Ni-ZZG full-cell rate performances, the batteries were first fully charged at 0.5 C (1 C = 280 mA g−1 based on the cathode) and then discharged to a cutoff potential of 1.0 V at different current densities from 0.5 to 10 C (2800 mA g−1 cathode). The long cycling tests were conducted at 5 C within 1.0 to 2.0 V. The energy and power densities were calculated on the basis of the total mass of active materials in the cathode and anode, except for a special illustration. For the Ni0.95Co0.3Zn0.2(OH)2-CuCO3·Cu(OH)2@graphene full cell, the long cycling tests were conducted at 5 C within 0 to 1.4 V. The CO32− transfer number of electrolyte was calculated by Bruce-Vincent-Evans equation: t(CO32−) = (Iss/I0)·(V − I0·R0)/(V − Iss·Rss), where I0 is the initial current and Iss is the steady-state current of the ZZG + Zn || 2 M K2CO3 || ZZG + Zn symmetrical cell after polarization for 2800 s at an applied polarization voltage of 10 mV. R0 and Rss are the initial interfacial resistance and steady-state interfacial resistance after the polarization process, respectively.

Pouch-type Ni-ZZG full batteries were fabricated by stacked technology. The cathode was prepared by mixing 93% active materials powder, 3% graphite, 2% carbon black, and 2% PTFE in water. The slurry mixture was then cast into nickel foam and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. Typically, the mass loading of the cathodes is about 108 mg cm−2. The electrodes were compressed under a pressure of 5 MPa, followed by cutting into rectangles with a size of 40 mm × 20 mm. The anode was prepared by mixing 91% ZZG powder, 3% graphite, 2% carbon black, 1% In2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), 1% Bi2O3 powder (99.99% purity, 500 mesh), and 2% PTFE in water. The slurry mixture was then coated on a brass mass and dried at 70°C overnight in a vacuum oven. The typical mass loading of ZZG was about 60 mg cm−2. All electrodes were compressed under a pressure of 0.1 MPa, followed by cutting into rectangles with a size of 41 mm × 21 mm. The negative-to-positive active material capacity ratio was controlled to 1.05. Five cathodes, six anodes, and nine separators (43 mm × 23 mm) were then stacked layer by layer. Four grams of 2 M K2CO3 + 0.1 M KOH weak alkaline electrolyte was injected and allowed to stand for one night, followed by the sealing of pouch batteries. Before testing, the batteries were first fully charged at 0.5 A and then discharged to a cutoff potential of 1.0 V to activate the battery. The cycling tests were conducted at 1 A within a voltage range of 1.2 to 2.0 V.

Computational methodology

GROMACS software (43, 44) was used to perform the classical molecular dynamics simulations and the AMBER force field together with the TIP3P water model. A cubic box of 30 Å was used, and periodic boundary conditions were set in all three directions. The electrostatic interactions were computed using particle-mesh Ewald methods. A cutoff length of 1.0 nm was used for both electrostatic interactions and nonelectrostatic interactions in real space. The integration time step was 1 fs. The temperature and pressure coupling were performed in V-rescale and Parrinello-Rahman methods, respectively. These systems were minimized by the steepest descent method to limit the maximum force within 1000.0 kJ/(mol·nm), followed by equilibration in NVT ensemble for 1 ns at 298.15 K. A simulation of 10 ns in NPT ensemble at 1 bar was performed to reach the equilibrium (N, number of particles; V, volume; P, pressure; T, temperature). The resulting temperature, pressure, and density of these systems are displayed in fig. S2, which validates the simulation setups. Last, a 10-ns production simulation in a preequilibrated NPT ensemble was run for a postprocessing analysis of mean square displacement and radial distribution functions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52102261; 22109029), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210942), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (22ZR1403600), Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (20KJB150007), and Changzhou Science and Technology Young Talents Promotion Project (KYZ21005). D.C. thanks the financial support from Fudan University (nos. JIH2203010 and IDH2203008/003).

Author contributions: Z.H. and D.C. conceived the idea. Z.X. and W.Z. carried out the synthesis. Z.H., T.Z., J.L., and H.J.F. carried out the material characterizations and electrochemical evaluation. X.L. performed the simulations. Z.H., D.C., Y.Q., and D.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S39

Tables S1 to S3

Notes S1 to S6

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Pan H., Shao Y., Yan P., Han K. S., Nie Z., Wang C., Yang J., Li X., Bhattacharya P., Mueller K. T., Liu J., Reversible aqueous zinc/manganese oxide energy storage from conversion reactions. Nat. Energy 1, 1–7 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kundu D., Adams B. D., Duffort V., Vajargah S. H., Nazar L. F., A high-capacity and long-life aqueous rechargeable zinc battery using a metal oxide intercalation cathode. Nat. Energy 1, 1–8 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F., Borodin O., Gao T., Fan X., Sun W., Han F., Faraone A., Dura J. A., Xu K., Wang C., Highly reversible zinc metal anode for aqueous batteries. Nat. Mater. 17, 543–549 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song M., Tan H., Chao D., Fan H. J., Recent advances in Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802564 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao D., Zhou W., Xie F., Ye C., Li H., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.-Z., Roadmap for advanced aqueous batteries: From design of materials to applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4098 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu C., Li B., Du H., Kang F., Energetic zinc ion chemistry: The rechargeable zinc ion battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 933–935 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita M., Sano M., Hayakawa Y., Honjo H., Sawada Y., Fractal structures of zinc metal leaves grown by electrodeposition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 286–289 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grier D., Ben-Jacob E., Clarke R., Sander L.-M., Morphology and microstructure in electrochemical deposition of zinc. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 1264–1267 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLarnon F. R., Cairns E. J., The secondary alkaline zinc electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 138, 645–656 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bass K., Mitchell P., Wilcox G., Smith J., Methods for the reduction of shape change and dendritic growth in zinc-based secondary cells. J. Power Sources 35, 333–351 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 11.T. B. Reddy, Linden’s Handbook of Batteries (McGraw-Hill, 2011), vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao J., Long J., Li B., Li X., Zhang S., Hua F., Zeng X., Yang Z., Pang W., Guo Z., Toward high-performance hybrid zn-based batteries via deeply understanding their mechanism and using electrolyte additive. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1903605 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q., Luan J., Fu L., Wu S., Tang Y., Ji X., Wang H., The three-dimensional dendrite-free zinc anode on a copper mesh with a zinc-oriented polyacrylamide electrolyte additive. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15841–15847 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun P., Ma L., Zhou W., Qiu M., Wang Z., Chao D., Mai W., Simultaneous regulation on solvation shell and electrode interface for dendrite-free Zn ion batteries achieved by a low-cost glucose additive. Angew. Chem. 133, 18395–18403 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan Z., Liu X., Xu W., Duan Y., Zhang H., Li X., Negatively charged nanoporous membrane for a dendrite-free alkaline zinc-based flow battery with long cycle life. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J., Yin J., Zhang D., Li G., Block D. C., Tang T., Zhao Q., Liu X., Warren A., Deng Y., Jin S., Marschilok A. C., Takeuchi E. S., Takeuchi K. J., Rahn C. D., Archer L. A., Spontaneous and field-induced crystallographic reorientation of metal electrodeposits at battery anodes. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1122 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao L., Li D., Pollad T., Deng T., Zhang B., Yang C., Chen L., Vatamanu J., Hu E., Hourwitz M. J., Ma L., Ding M., Li Q., Hou S., Gaskell K., Fourkas G. T., Yang X.-Q., Xu K., Borodin O., Wang C., Fluorinated interphase enables reversible aqueous zinc battery chemistries. Nat. Nanotech. 16, 902–910 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao J., Li X., Zhang S., Yang F., Zeng X., Zhang S., Bo G., Wang C., Guo Z., Designing dendrite-free zinc anodes for advanced aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2001263 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z., Hu J., Han L., Wang Z., Wang H., Zhao Q., Liu J., Pan F., A MOF-based single-ion Zn2+ solid electrolyte leading to dendrite-free rechargeable Zn batteries. Nano Energy 56, 92–99 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie X., Liang S., Gao J., Guo S., Guo J., Wang C., Xu G., Wu X., Chen G., Zhou J., Manipulating the ion-transfer kinetics and interface stability for high-performance zinc metal anodes. Energ. Environ. Sci. 13, 503–510 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao L., Li D., Deng T., Li Q., Wang C., Hydrophobic organic-electrolyte-protected zinc anodes for aqueous zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19292–19296 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui Y., Zhao Q., Wu X., Chen X., Yang J., Wang Y., Qin R., Ding S., Song Y., Wu J., Yang K., Wang Z., Mei Z., Song Z., Wu H., Jiang Z., Qian G., Yang L., Pan F., An interface-bridged organic–inorganic layer that suppresses dendrite formation and side reactions for ultra-long-life aqueous zinc metal anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16594–16601 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker J. F., Chervin C. N., Pala I. R., Machler M., Burz M. F., Long J. W., Rolison D. R., Rechargeable nickel–3D zinc batteries: An energy-dense, safer alternative to lithium-ion. Science 356, 415–418 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao D., Zhu C., Song M., Liang P., Zhang X., Tiep N. H., Zhao H., Wang J., Wang R., Zhang H., Fan H. J., A high-rate and stable quasi-solid-state zinc-ion battery with novel 2D layered zinc orthovanadate array. Adv. Mater. 30, e1803181 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J., Zhao Q., Tang T., Yin J., Quilty C. D., Renderos G. D., Liu X., Deng Y., Wang L., Bock D. C., Jaye C., Zhang D., Takeuchi E. S., Takeuchi K. J., Marschilok A. C., Archer L. A., Reversible epitaxial electrodeposition of metals in battery anodes. Science 366, 645–648 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes P. P., Stamenkovic V. R., Past, present, and future of lead–acid batteries. Science 369, 923–924 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.H. Bode, Lead-Acid Batteries (John Wiley and Sons Inc., 1977). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Y., Yang J., Hu J., Wang J., Liang S., Hou H., Wu X., Liu B., Yu W., He X., Kumar R. V., Lead-carbon batteries: Synthesis of nanostructured PbO@C composite derived from spent lead-acid battery for next-generation lead-carbon battery (Adv. Funct. Mater. 9/2018). Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1870056 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.D. Pavlov, Lead-Acid Batteries: Science and Technology, D. Pavlov, Ed. (Elsevier, 2011), pp. 29–114. [Google Scholar]

- 30.W. M. Haynes, CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (CRC Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 31.J. G. Speight, Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry (McGraw-Hill Education, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z., Yuan T., Pu X., Yang H., Ai X., Xia Y., Cao Y., Symmetric sodium-ion capacitor based on Na0. 44MnO2 nanorods for low-cost and high-performance energy storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 10, 11689–11698 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J., Chen M., Zhang L., Jiang J., Yan J., Huang Y., Lin J., Fan H. J., Shen Z. X., A flexible alkaline rechargeable ni/fe battery based on graphene foam/carbon nanotubes hybrid film. Nano Lett. 14, 7180–7187 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randles J. E., A cathode ray polarograph. Part II. The current-voltage curves. Trans. Faraday Soc. 44, 327–338 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou W., Zhu D., He J., Li J., Chen H., Chen Y., Chao D., A scalable top-down strategy toward practical metrics of Ni–Zn aqueous batteries with total energy densities of 165 W h kg−1 and 506 W h L−1. Energ. Environ. Sci. 13, 4157–4167 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uñates M. E., Folquer M. E., Vilche J. R., Arvia A. J., The influence of foreign cations on the electrochemical behavior of the nickel hydroxide electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 139, 2697–2704 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang G., Zhu J., Yan B., Li Q., Chen A., Chen Z., Wang X., Xiong B., Fan J., Xu J., Zhi C., Gradient fluorinated alloy to enable highly reversible Zn-metal anode chemistry. Energ. Environ. Sci. 15, 1086–1096 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang N., Cheng F., Liu J., Wang L., Long X., Liu X., Li F., Chen J., Rechargeable aqueous zinc-manganese dioxide batteries with high energy and power densities. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suo L., Borodin O., Gao T., Olguin M., Ho J., Fan X., Luo C., Wang C., Xu K., “Water-in-salt” electrolyte enables high-voltage aqueous lithium-ion chemistries. Science 350, 938–943 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F., Borodin O., Ding M. S., Gobet M., Vatamanu J., Fan X., Gao T., Eidson N., Liang Y., Sun W., Greenbaum S., Xu K., Wang C., Hybrid aqueous/non-aqueous electrolyte for safe and high-energy li-ion batteries. Joule 2, 927–937 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang F., Lin Y., Suo L., Fan X., Gao T., Yang C., Han F., Qi Y., Kang X., Wang C., Stabilizing high voltage LiCoO2 cathode in aqueous electrolyte with interphase-forming additive. Energ. Environ. Sci. 9, 3666–3673 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada Y., Usui K., Sodeyama K., Ko S., Tateyama Y., Yamada A., Hydrate-melt electrolytes for high-energy-density aqueous batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 1–9 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abraham M. J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J. C., Hess B., Lindahl E., GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pronk S., Páll S., Schulz R., Larsson P., Bjelkmar P., Apostolov R., Shirts M. R., Smith J. C., Kasson P. M., Van Der Spoel D., Hess B., Lindahl E., GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 29, 845–854 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kresse G., Furthmuller J., Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S39

Tables S1 to S3

Notes S1 to S6

References