Abstract

The major antigenic protein 1 fragment B (MAP1-B) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the diagnosis of Cowdria ruminantium infections was validated to determine cutoff values and evaluate its diagnostic performance with sheep and goat sera. Cowdria-infected populations consisted of 48 sheep and 44 goats, while the noninfected populations consisted of 64 sheep and 107 goats. Cutoff values were determined by two-graph receiver-operating characteristic (TG-ROC) curves. The cutoff value was set at 31 and 26.6% of the positive control reference samples for sheep and goat sera, respectively. The test’s diagnostic performance was evaluated with measurements of the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of the ROC curves and by the valid range proportion (VRP). The AUCs were 0.978 for sheep sera and 0.989 for goat sera. The VRP for both sheep and goat sera was approximately 1.0. The intermediate range (IR), which defines results that are neither positive nor negative, was 0 for goat sera and 2.81 for sheep sera. In an ideal test, the AUC and VRP would be 1.0 and the IR would be 0. In this study these parameters were close to those of an ideal test. It is concluded that the MAP1-B ELISA is a useful test for the diagnosis of C. ruminantium infection in small ruminants.

Cowdriosis (or heartwater) is a tick-borne disease of ruminants caused by the rickettsia Cowdria ruminantium and is transmitted by ticks of the genus Amblyomma. The disease is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean and is a main obstacle to livestock development in the tropics (7, 30). Clinical signs and macroscopic postmortem changes are not pathognomonic for the disease, and diagnosis is based on the detection of rickettsial organisms in the cytoplasms of endothelial cells in brain capillaries. Antemortem tests for detecting C. ruminantium include animal subinoculation, cell culture isolation, serodiagnostic tests, DNA hybridization, and PCR. Serodiagnostic methods, such as the indirect fluorescent antibody test, immunoblotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), have been hampered by cross-reactions with Ehrlichia species (18, 22, 24). However, the use of recombinant major antigenic protein 1 (MAP1) of C. ruminantium has been recently introduced, and an indirect ELISA based on a specific fragment of this protein (fragment B, referred to herein as MAP1-B) has been developed (32). Cross-reactions were dramatically reduced, although sera from dogs infected with Ehrlichia canis and sera from human patients infected with Ehrlichia chaffeensis were also positive in this ELISA. Another recent study, using a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA for detecting MAP1, confirmed cross-reactions with E. canis, E. chaffeensis, and a newly discovered Ehrlichia-like organism from white-tailed deer (21). Furthermore, it has also been shown that E. chaffeensis can experimentally infect wild ruminants such as white-tailed deer (5). A preliminary validation of the MAP1-B ELISA was done by studying antibody profiles of C. ruminantium infections in domestic ruminants (25, 32).

Central to any serological assay is the determination of the diagnostic cutoff value. It is common practice to determine cutoff values for (i) reactions of a noninfected reference population with the addition of 2 or 3 standard deviations to the mean value or (ii) the doubling of the mean optical density readings of the negative reference sera on each ELISA plate (26). The first method is assumed to lead to a specificity of 97.5% (2); however, this assumption holds true only for normally distributed test variables (12), and the second method seems to have no statistical grounds. A cutoff value has to differentiate two subpopulations of infected and noninfected controls with defined operating characteristics (13). Recently a new approach to defining test cutoff values and performance had been proposed (13). The new approach utilizes the conventional receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) principle, modified in such a way that the test sensitivity and specificity can be read directly from these plots, unlike the conventional ROC plots. The modified ROC plot is known as a two-graph ROC (TG-ROC). TG-ROC was developed as a template within a standard spreadsheet computer program, and it provides a clear and comprehensible approach to the problems of selecting cutoff values and identifying intermediate results in ELISA tests (10). TG-ROC analysis also provides other indices, such as efficiency (9), Youden’s index (35), and likelihood ratio (LR) (28), for further cutoff value optimization. These indices are useful measures for minimizing the number of false positives and false negatives.

The aims of this study were (i) to calculate cutoff values for the MAP1-B ELISA for the diagnosis of cowdriosis with TG-ROC, (ii) to compare these values to those determined by conventional methods with sheep and goat serum samples, and (iii) to compare the performance of the MAP1-B ELISA for the diagnosis of cowdriosis in experimentally infected sheep and goats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. ruminantium isolates.

The following C. ruminantium isolates (from the following locations) were used in this study: Senegal (Senegal), Lutale (Zambia) (19), Umpala (Mozambique) (1), Gardel (Guadeloupe) (31), and Crystal Springs (Zimbabwe) (4) and Ball 3 (14), Kümm (8), Kwanyanga (23), and Welgevonden (6) (all from South Africa).

Experimental animals.

Forty-eight adult female Tesselaar sheep, all nonpregnant and 12 to 18 months old, were used as the infected reference sheep population. The animals were challenged with different C. ruminantium isolates by needle infection 1 month after vaccination with an attenuated Cowdria isolate originating from Senegal (17, 20). Twenty-four sheep were challenged with the Senegal isolate, four with Welgevonden, and five sheep each with the Umpala, Lutale, Gardel, and Ball 3 isolates. The sera used in this study were collected between 4 and 8 weeks postchallenge. The infected reference population of Saanen goats was composed of 44 goats, of both sexes and 12 to 18 months old, experimentally infected by needle challenge with one of several isolates of C. ruminantium: Gardel (n = 1), Senegal (n = 16), Lutale (n = 1), Ball 3 (n = 5), Kwanyanga (n = 5), Kümm (n = 8), Crystal Springs (n = 3), and Welgevonden (n = 5). The infective dose of the different isolates was previously determined in experimental animals. All animals were tested serologically prior to infection and were shown to be negative. The animals had never been exposed to ticks and were born and bred in The Netherlands. The noninfected reference population of sheep consisted of 64 adult Tesselaar sheep, and the noninfected reference population of goats consisted of 107 Saanen goats. As with the infected reference population, the noninfected animals had never been exposed to ticks and were born and bred in The Netherlands.

Recombinant MAP1-B antigen.

The immunogenic region of the MAP1 protein (MAP1-B) was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli with expression vector pQE9, as a fusion protein with six histidine residues added at the N terminus (32). Recombinant MAP1-B was purified with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose under denaturing conditions as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.).

ELISA.

One hundred microliters per well was used in all the steps described below. MAP1-B antigen was diluted (1.4 μg/ml) in coating buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3 [pH 9.6]) and immobilized onto 96-well ELISA plates (Microlon Multibind immunoassay plates; Greiner Labortechnik, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) by incubation for 1 h at 37°C and then stored overnight at 4°C. Plates were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.3, supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% nonfat dry milk [PBSTM]) (Protifar; Nutricia, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands). Plates were washed three times with PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and subsequently incubated with sera (diluted 1:200) in PBSTM for 1 h at 37°C. All samples were analyzed in duplicate on the same plate. Plates were washed three times with PBST and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with rabbit anti-goat or rabbit anti-sheep antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (RαG/IgG[H+L]/PO or RαSh/IgG[H+L]/PO; Nordic, Tilburg, The Netherlands) diluted in PBSTM (rabbit anti-goat antibodies, 1:1,500; rabbit anti-sheep antibodies, 1:1,750). ELISA plates were washed three times with PBST, and freshly prepared ABTS [2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid)] substrate was added.

Color development was allowed for 30 min in the dark, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm with an ELISA reader (Ceres UV 900 C; Biotek Instruments BV, Abcoude, The Netherlands). Each plate contained one positive and one negative reference serum sample. The means of the duplicate measurements were calculated, and the optical density was expressed as a percentage positive (PP) value of the reference positive control.

ROC plots.

ROC plots were constructed by using the vector of 1-Spj, where Spj is the test specificity at a cutoff value (dj) on the x axis and the vector of corresponding sensitivity (Sej) values on the y axis.

The performance of the test was evaluated by calculating the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of the ROC plot. The AUC is given by the test statistic U of the Mann-Whitney U test (15) and is determined by the following equation: AUC = U/np · nn, where U = np · nn + [nn · nn + 1)/2] − R, R is the rank sum of the noninfected sample, and np and nn are the numbers of infected and noninfected animals, respectively.

TG-ROC analysis.

TG-ROC analysis was carried out with the template described by Greiner et al. (13). For the construction of TG-ROC plots, the measurement range (MR), as observed for each pair of reference populations, was evenly divided into 250 intervals, with the resulting limits termed cutoff values (dj). Sej and Spj were calculated for each threshold dj value obtained. The resulting matrix of dj and the corresponding percentages of Sej and Spj were plotted to represent the two observed parameters over the specified range of PP values. The intersection of the sensitivity curve with the specificity curve is at (d0,θ0) and is called the “point of equivalence,” whereby cutoff value d0 yields equivalent test parameters (Sej = Spj = θ0). Two alternative cutoff values, which are the lower and upper limits of the intermediate range (IR), are defined at an accuracy level of 95%. In this study, the IR upper and lower limits were nonparametrically defined as the 95th and 5th percentile of the noninfected and infected reference populations, respectively. The valid range proportion (VRP) was determined as (MR− IR)/MR, where MR is calculated by PPmax− PPmin, with PPmax and PPmin being the highest and lowest ELISA PP values in the combined populations of infected and noninfected animals for each species.

The results for the noninfected reference populations of sheep and goats were used to calculate cutoff values (means ± 2 or 3 standard deviations). The negative reference sample on the ELISA test plates was used to determine cutoff values by the method of twice the negative.

Efficiency, Youden’s index, and LRs.

Three indices were calculated for further cutoff value optimization. Efficiency (at cutoff value dj) was calculated as follows: Efj = P · Se + (1 − P) · Spj, where P denotes the proportion of the reference infected sample. Youden’s index was determined by the following equation: Jj = (ad − bc)/(a + b)(c + d), where the sum of a and b is the number of infected animals a is the number of correctly diagnosed infected animals and b is the number of false negatives) and the sum of c and d is the number of noninfected animals (d is the number of correctly diagnosed animals and c is the number of false positives) at cutoff value dj. Positive and negative LRs (LR+ and LR−, respectively) for each cutoff value (dj) were calculated by the following equations: LR+ = Sej/(1 − Spj) and LR− = (1 − Sej)/Spj. The ratios were logarithmically transformed to give a symmetry, with a log(LR+) of 0 and a log(LR−) of 0 for a test yielding no information and a log(LR+) of ∞ and a log(LR−) of −∞ for an ideal test. The values of the indices were then plotted against the cutoff value.

RESULTS

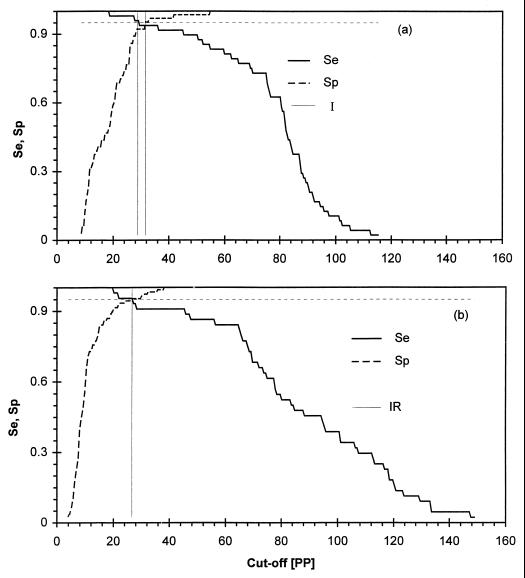

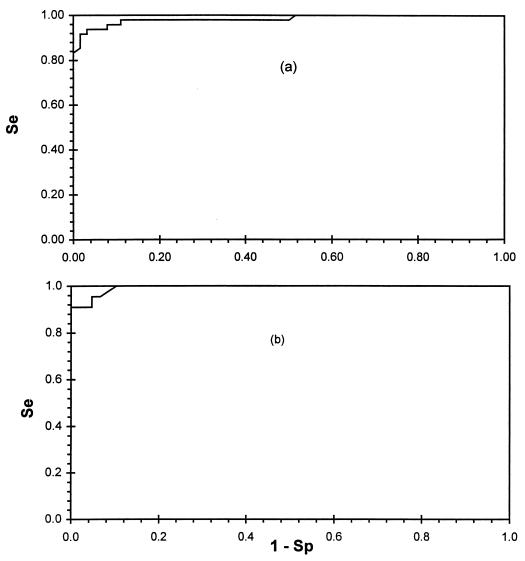

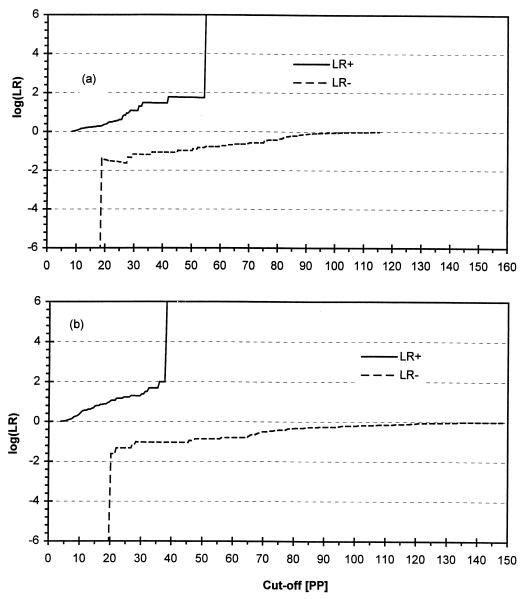

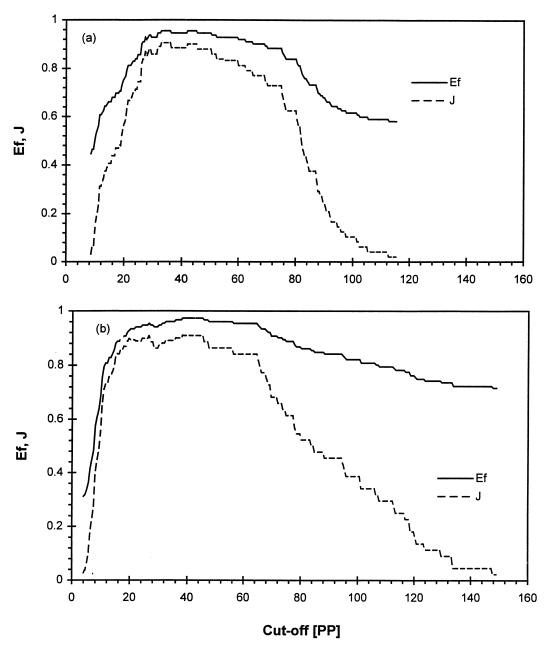

PP values for the infected and noninfected reference sheep and goat populations were tested for normality and showed significant skewness (P < 0.05). Therefore, the nonparametric option of the TG-ROC analysis was used (13). Table 1 summarizes the results of the MAP1-B ELISA for the populations of sheep and goats. The cutoff values resulting in equal sensitivity and specificity, as well as two alternative cutoff values for definition of the IR, were read directly from the TG-ROC plot in Fig. 1 and are shown in Table 2. The VRP was approximately 1.0 for sheep as well as for goats. The IR for goat sera was zero, because at cutoff value d0, sensitivity and specificity are both greater than 95%. The sensitivity and specificity measures of the test at cutoff value d0 are shown in Table 3. Calculated cutoff values for sheep and goats varied considerably according to the different methods shown in Table 3. The cutoff values calculated by TG-ROC analysis for sheep (d0 = 31.0) and for goats (d0 = 26.6) were close to those calculated as the mean plus twice the standard deviation (assuming normal distribution of the data). The performance of the test as measured by the AUC of the ROC plots was very close to 1: 0.978 for sheep and 0.989 for goats (Fig. 2). The LRs in Table 3 were calculated from the TG-ROC analysis and are displayed in Fig. 3, which shows graphs of the LRs over the entire range of possible cutoff values within the measurement range. The efficiency of the test, measured by efficiency and Youden’s index, is shown in Fig. 4. The closer to 1 the indices are, the better the test’s performance at a given cutoff value, dj.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive indices for the results of the MAP1-B ELISA for infected and noninfected reference populations of sheep and goatsa

| Measurement | % of sera positive from:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected

|

Noninfected

|

|||

| Sheep (48) | Goats (44) | Sheep (64) | Goats (107) | |

| Mean | 77.1 | 83.4 | 18.8 | 11.5 |

| Median | 81.6 | 81.1 | 18.9 | 9.2 |

| SD | 21.2 | 35.6 | 8.8 | 7.7 |

| Minimum | 18.2 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 3.3 |

| Maximum | 115.2 | 148.5 | 54.5 | 37.6 |

Results are expressed as percentages of an internal positive control. The number of animals in each group is indicated in parentheses.

FIG. 1.

TG-ROC analysis of MAP1-B ELISA results for sheep (a) and goat (b) sera. The IR is determined by using one cutoff value at 95% sensitivity (Se) and another at 95% specificity (Sp).

TABLE 2.

Results of TG-ROC analysisa

| Measurement | Result of TG-ROC analysis (CI) on sera from:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Goats | |

| θ0 | 94.5 | 95.4 |

| d0 | 31.0 (27–50) | 26.6 (20–36) |

| IR | 2.8 (0–36) | 0 |

| Upper limit | 31.7 (27–54) | 26.2 (20–36) |

| Lower limit | 28.8 (18–45) | 26.5 (19–45) |

| VRP | 0.97 (0.662–1) | 1 |

θ0, point of equivalence where specificity is equal to sensitivity at cutoff value d0; lower limit, 5th percentile of the percent positivity of the infected population; upper limit, 95th percentile of the percent positivity of the noninfected population. The 95% confidence internal (CI) is shown where appropriate.

TABLE 3.

Cutoff values determined by different methods with their corresponding sensitivities, specificities, and LRsa

| Result | Source of sera | Mean + 2 SDs | Mean + 3 SDs | 2× negative | TG-ROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutoff | S | 36.34 | 45.11 | 17.54 | 31.00 |

| G | 26.90 | 31.26 | 13.48 | 26.60 | |

| Sensitivity (%) | S | 94 | 87 | 100 | 94.50 |

| G | 90 | 90 | 100 | 95.40 | |

| Specificity (%) | S | 97 | 98 | 50 | 94.50 |

| G | 95.40 | 98 | 80 | 95.40 | |

| LR+ | S | 4.48 | 6.05 | 1.22 | 2.27 |

| G | 3.47 | 4.48 | 1.65 | 3.32 | |

| LR− | S | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| G | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

S, sheep sera; G, goat sera; SD, standard deviation for the noninfected reference population; mean, mean value of the negative reference population; 2× negative, twice the value of the negative reference population; LR+, positive LR; LR−, negative LR. The sensitivities, specificities, and LRs were calculated by TG-ROC analysis.

FIG. 2.

ROC plots of MAP1-B ELISA results for sheep (a) and goat (b) sera. The AUCs are 0.978 and 0.989, respectively (maximum AUC = 1.0).

FIG. 3.

Logarithm of negative (LR−) and positive (LR+) LRs plotted as a function of the selected cutoff value with sheep (a) and goat (b) sera.

FIG. 4.

Youden’s index (J) and efficiency (Ef) of the MAP1-B ELISA as a function of the selected cutoff value for sheep (a) and goat (b) sera.

DISCUSSION

The aims of this study were to determine cutoff values by TG-ROC analysis, to compare them to those obtained by previously used methods, and to evaluate the performance of the MAP1-B ELISA for the diagnosis of C. ruminantium infections in sheep and goats.

The establishment of a reliable cutoff value is essential for a serological test to be useful in differentiating infected and noninfected animals. The assembly of the reference population used for the calculation of a cutoff value is a critical procedure: the sample size has to be large enough to provide the desired statistical power, and moreover, the reference population has to be representative of the target population (12). In order to compensate for various factors that may influence the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, R. Jacobson (16) suggested the use of at least 300 known positive and 1,000 known negative samples, which numbers are very difficult to obtain under experimental conditions. We conducted this study with the minimal number of positive samples required for a meaningful analysis. We did not have any further positive samples in stock (sera from 48 sheep and 44 goats), but a significant number of noninfected samples (sera from 64 sheep and 107 goats) were available. The latter precondition is very difficult to realize for ELISA tests designed for the screening of tropical infectious diseases: control sera from animals in regions where heartwater is not endemic are guaranteed to be disease free but might not be representative of the target population; on the other hand, negative sera from animals in regions where heartwater is endemic might not be guaranteed to be disease free (33, 34). Previously, determination of cutoff values for the MAP1-B ELISA has mainly been done by doubling the PP value of a reference noninfected sample included on each plate. As shown in Table 3, doubling the PP value of the reference noninfected serum results in a very low specificity and low positive LR for the test. Hence, a single reference sample can serve as an internal test control but can hardly be considered an adequate representation of a noninfected population. Mondry et al. (25) based their cutoff values for the MAP1-B ELISA on the frequency distribution of PP values for a noninfected population in the Caribbean. In their study, cutoff values were determined graphically on the basis of an acceptable number of false-positive results. The authors, however, did not explain how an acceptable number of false positives was defined. The values obtained were fixed at 50% positive for sheep and goats. An overall specificity of 99.4% was reported, but the effect of the cutoff value on the test sensitivity was not investigated in a large enough population of known infected animals.

TG-ROC plots are graphs that show the relationship between the sensitivity and specificity of a test wherein the definition of a positive test is modified over the entire range of obtained values. ROC curves make it possible to compare the quality of the tests with the quality of other quantitative tests and allow a systematic and objective choice of optimal cutoff values (29). Reporting only one value for sensitivity and specificity provides a possibly misleading and even hazardous oversimplification of accuracy. Similarly, calculating just a few sensitivity and specificity pairs provides only a glimpse of a test’s real diagnostic abilities (36). The TG-ROC method was originally tested on data obtained with an ELISA for the detection of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi (13) and also was used to evaluate another ELISA test for the diagnosis of maedi-visna virus (3), giving encouraging results.

Given the difficulties of obtaining animals not exposed to Cowdria or ticks in areas where cowdriosis is endemic, we recommend that the cutoff values for these areas be those given by the mean plus 2 standard deviations, if negative samples from regions of endemicity are available, or to use cutoff d0 (31.0 and 26.6% positive for sheep and goats, respectively [Tables 2 and 3]), if no such sera are available. The method using the mean plus 2 standard deviations gave results that are quite similar to those obtained by the TG-ROC method. However, a cutoff value should be determined with defined diagnostic accuracy (13), which is not the case with the conventional methods. In this study, the values of d0 correspond to the efficiency and Youden’s index’s highest values (Fig. 4). In TG-ROC plots (Fig. 1) an option is given such that the cutoff values can be chosen to suit the required level of accuracy and the effect of the selected cutoff value on the sensitivity and specificity of the test can be read directly from the plots. Likewise, the efficiency, Youden’s index, and LRs for the MAP1-B ELISA can be read directly from the plots in Fig. 3 and 4 for a selected cutoff value. Youden’s index has a value of 0 whenever a diagnostic test gives the same proportion of positives for both infected and noninfected groups (35).

The IR used to describe nonpositive and nonnegative test results was 2.81 for sheep and 0 for goats. The IR is 0 in cases where the θ0 is greater than 95%, because the lower limit of the IR is greater than the upper limit. In this study, the IR for goats was 0; hence, over 95% of the goats were correctly diagnosed. The interpretation of intermediate test results depends on the specific diagnostic purpose of the test. Because of the ambiguity of borderline results, it is appropriate to consider only one cutoff value and indicate the test parameters (Se, Sp, and LR) for a given cutoff value selected for an epidemiological situation. In clinical diagnosis, the values that fall between the IR limits would require testing by a confirmatory assay or retesting for detection of seroconversion (16, 27).

The VRP and θ0 are independent of any selected cutoff value and are, therefore, good measures for test comparison (13). In this study the VRP and θ0 were reasonably high (Table 2) for both sheeps and goats, indicating the high performance of this ELISA in classifying the animals according to their true health status. It can be concluded that 95% of individual test results are valid, because the VRP was close to 1.0 for both species.

Another convenient way to quantify the diagnostic accuracy of a test is to express its performance by AUC measurements of ROC plots. This is a quantitative, descriptive expression of how close the ROC curve is to the perfect one (AUC = 1.0) (36). AUCs in ROC curves provide an index of accuracy by demonstrating the limits of a test’s ability to discriminate between the alternative state of health and the complete spectrum of operating conditions, unlike in TG-ROC plots, where the VRP is limited to 95% accuracy. The MAP1-B ELISA showed high performance because the index AUCs were 0.978 and 0.989 for sheep and goat sera, respectively. From these results (VRP, AUC, and IR), the test appears to have no differences in its diagnostic performance for sheep and goats.

Decisions regarding cutoff values for this ELISA should be reviewed as more data become available, since experimental infections sometimes produce an overoptimistic estimate of accuracy. Analysis similar to that done with sheep and goat sera needs to be done for bovine samples, and work on this has already been started in our laboratory. The effect of the cutoff values on the antibody profiles of ruminants should also be investigated for further cutoff value optimization.

Studies have shown that age is positively correlated with seropositivity but not with the detection of the parasite when a Trypanosoma antibody-detecting ELISA was used in an area in Uganda where trypansomiasis is endemic (11). In addition to age, many other factors (such as sex, breed, state of pregnancy, nutritional state, previous chemotherapy, passive immunization, and self-cured infections) may also influence the cutoff value. Further validation of the test precision needs to be done according to the ISO 5725-1986 international procedure, with interlaboratory comparisons of the ELISA results.

In this study we have attempted to calculate cutoff values by using known positive and negative experimental sera. It will be of great interest to repeat this study using samples from animals exposed to infected Amblyomma ticks under field conditions to check whether our cutoff values (determined with experimental animals) are also applicable to the situation in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. W. C. A. Cornelissen and Mirjam Nielen for critically reading the manuscript; Daan Vink for providing the noninfected goat reference samples, and the staff of the experimental animal facility for good care of the experimental animals.

This research was carried out within the framework of the Concerted Action project on Integrated Control of Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases of the INCO-DC program of the European Union under contract IC18-CT95-0009 and was supported by INCO-DC project IC18-CT95-0008 on Integrated Control of Cowdriosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asselbergs, M., and F. Jongejan. Personal communication.

- 2.Barajas-Rojas J A, Riemann H P, Franti C E. Notes about determining the cut-off value in enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Prev Vet Med. 1993;15:231–233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boshoff C H, Dungu B, Williams R, Vorster J, Conradie J D, Verwoerd D W, York D F. Detection of Maedi-Visna virus antibodies using a single fusion transmembrane-core p25 recombinant protein ELISA and a modified receiver-operating characteristic analysis to determine cut-off values. J Virol Methods. 1997;63:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(96)02114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrom B, Yunker C E. Improved culture conditions for Cowdria ruminantium (Rickettsiales), the agent of heartwater disease of domestic ruminants. Cytotechnology. 1990;4:285–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00563789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson J E, Childs J E, Biggie K L, Moore C, Stallknecht D, Shaddock J, Bouseman J, Hofmeister E, Olson J G. White-tailed deer as a potential reservoir of Ehrlichia spp. J Wildl Dis. 1994;30:162–168. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-30.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Plessis J L. A method for determining the Cowdria ruminantium infection rate of Amblyomma hebraeum: effects in mice injected with tick homogenates. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1985;52:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Plessis J L, Bezuidenhout J D, Ludemann C J. The immunization of calves against heartwater: subsequent immunity both in the absence and presence of natural tick challenge. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1984;51:193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Plessis J L, Kümm N A L. The passage of Cowdria ruminantium in mice. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1971;42:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galen R S. Use of predictive value theory in clinical immunology. In: Rose N R, Friedman H, Fahey J L, editors. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1986. pp. 966–970. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greiner M. Two-graph receiver operating characteristic (TG-ROC): a Microsoft-EXCEL template for the selection of cut-off values in diagnostic tests. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:145–146. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00078-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greiner M, Bhat T S, Patzelt R J, Kakaire D, Schares G, Dietz E, Bohning D, Zessin K H, Mehlitz D. Impact of biological factors on the interpretation of bovine trypanosomosis serology. Prev Vet Med. 1997;30:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(96)01088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiner M, Franke C R, Bohning D, Schlattmann P. Construction of an intrinsic cut-off value for the sero-epidemiological study of Trypanosoma evansi infections in a canine population in Brazil: a new approach towards an unbiased estimation of prevalence. Acta Trop. 1994;56:97–109. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiner M, Sohr D, Gobel P. A modified ROC analysis for the selection of cut-off values and the definition of intermediate results of serodiagnostic tests. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00121-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haig D A. Note on the use of white mouse in the transport of strains of heartwater. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1952;23:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley J A, McNeil B J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson R. Office International des Epizooties Standards Commission (ed.), Manual of standards for diagnostic tests and vaccines. 3rd ed. Paris, France: Office International des Epizooties; 1996. Principles of validation of diagnostic assays for infectious diseases; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jongejan F. Protective immunity to heartwater (Cowdria ruminantium infection) is acquired after vaccination with in vitro-attenuated rickettsiae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:729–731. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.729-731.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jongejan F, de Vries N, Nieuwenhuijs J, Van Vliet A H M, Wassink L A. The immunodominant 32-kilodalton protein of Cowdria ruminantium is conserved within the genus Ehrlichia. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop. 1993;46:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongejan F, Uilenberg G, Franssen F F, Gueye A, Nieuwenhuijs J. Antigenic differences between stocks of Cowdria ruminantium. Res Vet Sci. 1988;44:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jongejan F, Vogel S W, Gueye A, Uilenberg G. Vaccination against heartwater using in vitro attenuated Cowdria ruminantium organisms. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop. 1993;46:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz J B, DeWald R, Dawson J E, Camus E, Martinez D, Mondry R. Development and evaluation of a recombinant antigen, monoclonal antibody-based competitive ELISA for heartwater serodiagnosis. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1997;9:130–135. doi: 10.1177/104063879700900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logan L L, Holland C J, Mebus C A, Ristic M. Serological relationship between Cowdria ruminantium and certain Ehrlichia. Vet Rec. 1986;119:458–459. doi: 10.1136/vr.119.18.458. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKenzie P K I, van Rooyen R F. The isolation and culture of Cowdria ruminantium in albino mice. In: Whitehead G B, Gibson J D, editors. International Congress on Tick Biology and Control. Grahamstown, South Africa: Rhodes University; 1981. pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahan S M, Tebele N, Mukwedeya D, Semu S, Nyathi C B, Wassink L A, Kelly P J, Peter T, Barbet A F. An immunoblotting diagnostic assay for heartwater based on the immunodominant 32-kilodalton protein of Cowdria ruminantium detects false positives in field sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2729–2737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2729-2737.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mondry R, Martinez D, Camus E, Liebisch A, Katz J B, Dewald R, van Vliet A H M, Jongejan F. Validation and comparison of three enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the detection of antibodies to Cowdria ruminantium infection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;849:262–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson M D, Turner A, Warnock D W, Llewellyn P A. Computer-assisted rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the serological diagnosis of aspergillosis. J Immunol Methods. 1983;56:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simel D L, Feussner J R, DeLong E R, Matchar D B. Intermediate, indeterminate, and uninterpretable diagnostic test results. Med Decis Making. 1987;7:107–114. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8700700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith R D. Evaluation of diagnostic tests. In: Smith R D, editor. Veterinary clinical epidemiology. Stoneham, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegeman J A, de Jong M C, van der Heijden H M, Elbers A R, Kimman T G. Assessment of the quality of tests for the detection of antibodies to Aujeszky’s disease virus glycoprotein gE in a target population by the use of receiver operating characteristic curves. Res Vet Sci. 1996;61:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5288(96)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uilenberg G. Heartwater (Cowdria ruminantium infection): current status. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1983;27:427–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uilenberg G, Camus E, Barre N. A strain of Cowdria ruminantium isolated in Guadeloupe (French West Indies) Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop. 1985;38:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Vliet A H M, van der Zeijst B A M, Camus E, Mahan S M, Martinez D, Jongejan F. Use of a specific immunogenic region on the Cowdria ruminantium MAP1 protein in a serological assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2405–2410. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2405-2410.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voller A. Serodiagnosis of tropical parasitic diseases with special reference to the standardization of labeled reagent tests. Dev Biol Stand. 1985;62:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voller A, Bidwell D E, Bartlett A, Edwards R. A comparison of isotopic and enzyme-immunoassays for tropical parasitic diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1977;71:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(77)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youden D. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zweig M H, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem. 1993;39:561–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]