Abstract

A significant proportion of brain tissue specimens from children with AIDS show evidence of vascular inflammation in the form of transmural and/or perivascular mononuclear-cell infiltrates at autopsy. Previous studies have shown that in contrast to inflammatory lesions observed in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) encephalitis, in which monocytes/macrophages are the prevailing mononuclear cells, these infiltrates consist mostly of lymphocytes. Perivascular mononuclear-cell infiltrates were found in brain tissue specimens collected at autopsy from five of six children with AIDS and consisted of CD3+ T cells and equal or greater proportions of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. Transmural (including endothelial) mononuclear-cell infiltrates were evident in one patient and comprised predominantly CD3+ T cells and small or, in certain vessels, approximately equal proportions of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. There was a clear preponderance of CD3+ CD8+ T cells on the endothelial side of transmural infiltrates. In active lesions of transmural vasculitis, CD3+ T-cell infiltrates exhibited a distinctive zonal distribution. The majority of CD3+ cells were also CD8+ and CD45RO+. Scattered perivascular monocytes/macrophages in foci of florid vasculitis were immunoreactive for the p24 core protein. In contrast to the perivascular space, the intervening brain neuropil was dominated by monocytes/macrophages, microglia, and reactive astrocytes, containing only scant CD3+ CD8+ cells. Five of six patients showed evidence of calcific vasculopathy, but only two exhibited HIV-1 encephalitis. One patient had multiple subacute cerebral and brainstem infarcts associated with a widespread, fulminant mononuclear-cell vasculitis. A second patient had an old brain infarct associated with fibrointimal thickening of large leptomeningeal vessels. These infiltrating CD3+ T cells may be responsible for HIV-1-associated CNS vasculitis and vasculopathy and for endothelial-cell injury and the opening of the blood-brain barrier in children with AIDS.

Neurological disease has emerged as an important manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in children. The clinical and pathological features of HIV-1-associated neurological disease in children differ considerably from those in adults, with an earlier, more severe, and, in some instances, more rapidly progressing neurological deterioration being evident in children (62, 64, 65, 68). Fifty to 80% of children with AIDS develop HIV-1-associated progressive encephalopathy, including cognitive impairment, developmental delays, psychomotor retardation, and behavioral manifestations (62). Progressive encephalopathy is associated directly with HIV-1 infection of the central nervous system (CNS) (6, 19). The majority of infected children show no evidence of CNS opportunistic infections or neoplasms (64, 68). Neuropathological evaluations have revealed that up to 40% of HIV-1-infected children exhibit HIV-1 encephalitis, similar to that observed in adult patients with AIDS, including perivascular multinucleated giant (syncytial) cells, foci of inflammatory cells, microglia, macrophages, and microglia nodules, as well as axonal and myelin degenerative changes and astrocytosis (6, 19).

One of the most characteristic pathological features of progressive CNS disease in HIV-1-infected pediatric patients is the presence of mineralization (calcification) of basal ganglia and of the frontal white matter, which is seen in over 85% of autopsy cases (11, 28, 64). This calcific vasculopathy, which involves both small vessels and large vessels, is frequently associated with HIV-1 encephalitis. In a large proportion of HIV-1-infected children, perivascular and, in certain cases, transmural mononuclear-cell infiltrates (vasculitis) consisting primarily of lymphocytes are concomitantly observed with mineralization of vessels (calcific vasculopathy) (13, 59, 62, 64, 68). The prevailing view is that vascular inflammation precedes calcific vasculopathy and is triggered by an immune response (13, 17, 59, 64, 65, 68). In addition, intimal fibroplasia of large- and medium-sized leptomeningeal arteries is also found in HIV-1-infected children, although it is seen considerably less frequently (13, 17, 59, 64, 65, 68). Cerebrovascular disease is commonly observed in HIV-1-infected children and may lead to stroke (13, 17, 59, 64, 68).

A major difference in neuropathological findings between adult patients and children with HIV-1 is that angiocentric mononuclear-cell infiltrates of the CNS, composed primarily of lymphocytes, are observed at autopsy in a substantial proportion of HIV-1-infected children (13, 17, 59, 64, 65, 68). Sharer et al. (64) reported vascular or perivascular inflammation involving small- or medium-sized arteries or veins in the brains of 5 of 11 HIV-1-infected children (ages 4 months to 11 years). In contrast to inflammatory lesions observed in HIV-1 encephalitis (where monocytes/macrophages are the prevailing mononuclear cells), these perivascular and/or transmural infiltrates are composed mostly of lymphocytes (64). In HIV-1-infected patients, cerebral vascular inflammation has been demonstrated without any evidence of an infectious cause, other than HIV-1 infection, and is distinctly different from HIV-1 encephalitis (26, 62, 77). Besides the morphological evaluation that these perivascular and/or transmural infiltrates contain lymphocytes, there is no other information on their characterization.

We report here the phenotypic characterization of perivascular and transmural mononuclear-cell infiltrates in the CNS of HIV-1-infected children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded brain tissue specimens collected at autopsy from six children with AIDS at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children were used in this study. The clinical systemic and neurological characteristics of these patients, as well as their treatment statuses, are described in Table 1. None of the patients exhibited coexistent opportunistic CNS infections or malignancy as determined by detailed clinical, pathological, neurological, and microbiological studies.

TABLE 1.

Patients’ histories of relevant medical and neurological clinical manifestations and their treatmenta

| Patient no. | Age | Clinical systemic manifestations | Neurological manifestations | Neurological diagnosisb | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 yr | FTT, oral thrush, asthma, LIP, pneumonia, anemia, lymphadenopathy | Acute onset of lethargy, ptosis, nystagmus, left gaze preference, ataxia | Acute encephalopathy | Corticosteroids |

| 2 | 3 yr | Oral thrush, LIP, gastroenteritis, UT1, thrombocytopenia, anemia, HAS, lymphadenopathy | Microcephaly, mild DD, mild spastic diparesis | Chronic static encephalopathy | i.v. IgG, corticosteroids |

| 3 | 36 mo | FTT, oral thrush, pneumonia, hepatitis, HSM, pancreatitis, coagulopathy, lymphadenopathy | Microcephaly, profound DD, severe spastic quadriparesis | Chronic markedly progressive encephalopathy | ZDV, ddI |

| 4 | 11 yr | Prematurity, meningitis and pneumonia at 1 year, deafness, hepatomegaly, hypertension, disseminated atypical mycobacterial infection, lymphadenopathy | Microcephaly, mild MR, moderate spastic quadriparesis | Chronic static encephalopathy | ZDV, i.v. IgG |

| 5 | 5 mo | FTT, oral thrush, Candida esophagitis, pneumocystis and CMV pneumonia, hepatitis, myocarditis and enteritis | Microcephaly, mild DD | Chronic static encephalopathy | i.v. IgG |

| 6 | 6 mo | FTT, oral thrush, pneumocystis pneumonia, gastroenteritis, CHF, HSM, anemia, lymphadenopathy | Microcephaly, mild DD, central hypotonia, mild spastic quadriparesis | Chronic static encephalopathy | ZDV, i.v. IgG |

All patients were male. Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral treatment; CHF, congestive heart failure; DD, developmental delay; ddI, didanosine; FTT, failure to thrive; HSM, hepatosplenomegaly; i.v., intravenous; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis; MR, mental retardation; UTI, urinary tract infection; ZDV, zidovudine.

Based on retrospective interpretation of available clinical data.

Tissue samples.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 5-μm-thick sections from the cerebrum, including grossly discernible lesions and multiple areas of the neocortex and limbic structures (hippocampus, amygdala, septal nuclei, and nucleus basalis of Meynert), hemispheric white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, subthalamus, and hypothalamus, as well as mesencephalon, pons, medulla, and cerebellum, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and with Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet for general histological evaluation. Special stainings for bacteria, mycobacteria, spirochetes, and fungi were performed and in all cases were negative.

MAbs.

The following monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were employed in this study: anti-CD3 MAb (clone PS-1; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom); anti-CD8 MAb (clone C8/144B; Dako, Glustrop, Denmark), anti-CD45RO MAb (clone UCHL1; Novocastra), anti-CD68 MAb (clone KP1; Dako), and anti-HIV p24 core protein (clone Kal-1; Dako). A mixture of two MAbs to cytomegalovirus (CMV) (clones DD69 and CCH2; Dako) and a mixture of four MAbs to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (clones CS1, CS2, CS3, and CS4; Dako) were used to evaluate coinfection.

Immunoperoxidase procedure.

The avidin-biotin complex (ABC)—immunoperoxidase procedure (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) was used as previously described (56). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min. Sections were incubated with normal horse serum, and the primary MAb, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, was then applied (at optimal concentrations according to the manufacturer’s specifications). Subsequently, sections were incubated with biotinylated, affinity-purified anti-immunoglobulin G (IgG), and then with ABC reagent (avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase). Diaminobenzidine was then used as a peroxidase substrate. Sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Antigen retrieval, achieved by heating tissue sections in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, was used for the purpose of staining with anti-CD3, anti-CD8, anti-CD45RO (certain experiments only), and anti-CD68 MAbs. Trypsin treatment was used for the anti-CMV and anti-EBV antibodies. In control slides, the primary MAbs were replaced by unrelated MAbs of the same Ig isotype, and all were nonreactive.

Analysis.

Manual counting was carried out independently by two observers (C.D.K. and J.F., who were blinded to the identity of the specimens) at an original magnification of ×400 with a gridded ocular lens. First, angiocentric mononuclear-cell infiltrates were identified at a low magnification. Subsequently, two histological patterns were identified, on the basis of the following criteria: (i) transmural vasculitis/endothelitis (TVE), defined as a distinct morphological pattern in which mononuclear cell infiltrates are found in the entire thickness of the vessel wall, including the endothelial lining; and (ii) perivascular (PV) infiltrates, mononuclear-cell infiltrates adjacent or around, but not through or across, the wall of the blood vessel (inflammatory cuffing). It should be noted that the transmural pattern is always associated with a perivascular component.

Mononuclear-cell infiltrates were rated on H&E preparations as follows: ++++, >130 mononuclear inflammatory cells per 10 high-power fields (HPF); +++, 100 to 129 mononuclear inflammatory cells per 10 HPF; ++, 10 to 99 mononuclear inflammatory cells per 10 HPF, +, <10 mononuclear inflammatory cells per 10 HPF; or −, no mononuclear inflammatory cells.

A determination of cell counts of positive cells recognized by any given antibody was made from the total number of immunostained cells in angiocentric foci containing TVE and/or PV infiltrates and, where appropriate, in conjunction with the total number of labelled cells in the intervening neuropil (modified from the procedure of Tyor et al. [72]). For each antibody, between 10 and 20 angiocentric foci were analyzed, as appropriate, at the original magnification of ×400. The distribution of CD3+, CD8+, CD45RO+, and CD68+ cells in TVE and PV infiltrates and in neuropil was determined immunohistochemically and rated as follows: ++++, >130 positive cells per 10 HPF; +++, 100 to 129 positive cells per 10 HPF; ++, 10 to 99 positive cells per 10 HPF; +, <10 positive cells per 10 HPF; or −, no positive cells. From 146 to 984 mononuclear cells were counted for these determinations. Interobserver agreement was within 15% (k = 0.82).

Vasculopathy was defined as disease of blood vessels irrespective of underlying etiology or pathogenesis. Two morphologically distinct forms were identified: (i) calcific vasculopathy, characterized by mineralized deposits (presumably calcium and iron salts) on the vessel walls and perivascular spaces; and (ii) intimal fibroplasia, characterized by extensive fibroproliferative changes with stenosis and/or obliteration of the vascular lumens.

Stroke in the context of this study was defined as a cerebral infarction, i.e., denoting an occlusive, rather than a hemorrhagic, nature. Temporally, it was either recently superimposed-on subacute or old. The anatomic extent of stroke was rated as follows: +++, a multifocal, multi-infarct state (more than three anatomically defined infarcts involving both cerebral hemispheres, i.e., cerebral cortex, hemispheric white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, brain stem, and cerebellum); ++, two infarcts involving one cerebral hemisphere; or +, a single, isolated infarct (not applicable in this series).

HIV-1 encephalitis is defined as cerebral inflammation involving gray matter (cortex and basal ganglionic, thalamic, hypothalamic, and subthalamic nuclei), hemispheric white matter, brain stem, and cerebellum. Histological hallmarks include scattered microglial nodules, perivascular multinucleated giant cells (representing cytopathic syncytia of monocytes/macrophages, as well as frequently displaying localization of HIV-1 antigens, such as p24 core protein), astrocytosis, diffuse (albeit somewhat circumscribed) myelin pallor, and a generalized, predominantly central brain atrophy.

RESULTS

Neuropathological findings.

Vascular inflammation of various proportions, characterized by mononuclear-cell infiltrates, was found in brain tissue specimens collected at autopsy from five of six children with AIDS (patients 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6). These results are summarized in Table 2. Anatomically, mononuclear-cell infiltrates were evident primarily in basal ganglionic regions, as well as in thalamic, subthalamic, and hypothalamic regions, deep hemispheric white matter, segmental portions of mesencephalon, and pons. TVE and PV histological patterns were recognized on the basis of the criteria described in Materials and Methods. PV infiltrates were found in five of six patients (no. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6). Patient 1 exhibited both TVE and PV infiltrates. Veins, and to a lesser extent arteries, of all calibers (small, medium and large) were involved, and they contained mostly perivascular cuffs of lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 1 and 2).

TABLE 2.

Angiocentric mononuclear-inflammatory-cell infiltrates in HIV-1-associated CNS disease in children: TVE, PV, vasculopathy, and stroke

| Patient no.a | Age | Mononuclear cell infiltratesb | Vasculopathyc | Stroked | Other neuropathological findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 yr | ++++ (TVE, PV) | Calcific vasculopathy | +++a | |

| 2 | 3 yr | ++ (PV) | Calcific vasculopathy Intimal fibroplasia, MCA, ACA | +b | |

| 3 | 8 yr | − | Calcific vasculopathy, severe | − | HIV-1 encephalitise |

| 4 | 11 yr | ++ (PV) | Calcific vasculopathy | − | Microcephaly; focal thrombosis and calcification of small meningeal vessels |

| 5 | 5 mo | ++ (PV) | Calcific vasculopathy | − | HIV-1 encephalitis |

| 6 | 6 mo | + (PV) | Not significant | − | Brain atrophy, numerous microglia cells in gliotic cerebral white matter; glioneuronal heterotopia, cerebellar white matter, incidental |

All patients were male.

TVE and PV infiltrates were defined as described in Materials and Methods.

Vasculopathy was defined as described in Materials and Methods.

Stroke in the context of this study was defined as cerebral infarction, i.e., denoting an occlusive, rather than a hemorrhagic, nature. Temporally, it is either recently superimposed-on subacute (a) or old (b). Anatomic extent was rated as described in Materials and Methods.

HIV-1 encephalitis was defined as described in Materials and Methods.

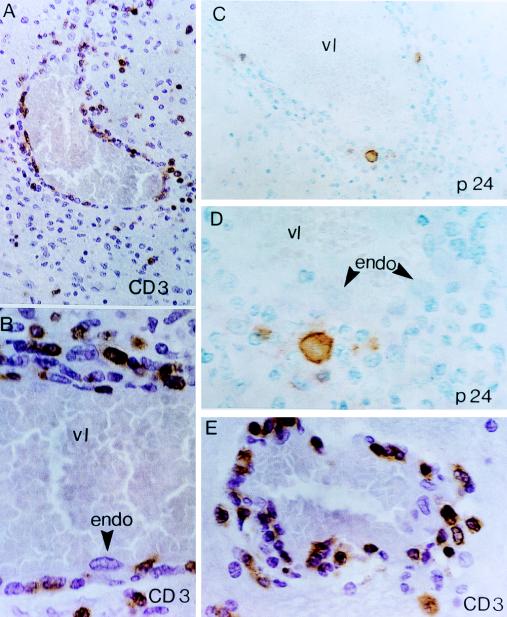

FIG. 1.

Mononuclear, predominantly lymphocytic vasculitis affecting medium-sized cerebral vessels in a 2-year-old HIV-1-infected child (patient 1) with multifocal cerebral infarcts. Medium-sized veins display a TVE pattern of inflammation. (A, B, and E) CD3+ T-cell infiltrates show a distinct proclivity for the walls and endothelial lining (endo) of intraparenchymal veins. The adjacent perivascular rim is composed of CD3+ T cells admixed with morphologically distinct monocytes/macrophages. vl, vascular lumen. (A) A representative field. The surrounding neuropil is dominated by cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage, including microglia, and contains only rare CD3+ T lymphocytes. (C and D) Localization of HIV-1 p24 core protein in scattered perivascular monocytes/macrophages in a blood vessel with TVE. The transmural infiltrate consists predominantly of lymphocytes (cells with smaller, slightly more hyperchromatic nuclei). Note the contiguous relationship of p24-positive monocytes, p24-negative lymphocytes, and p24-negative endothelial cells (arrowheads). ABC-immunoperoxidase was used for all panels; panels A, B, and E were counterstained with H&E, and panels C and D were counterstained with methyl green. Original magnifications, ×400 (A and C) and ×1,000 (B, D, and E).

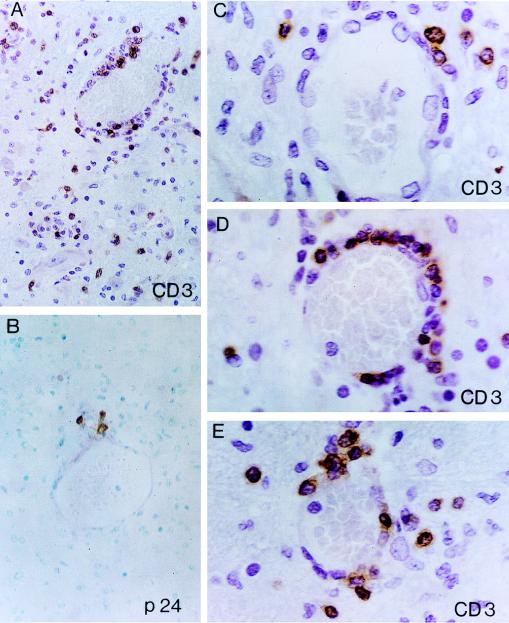

FIG. 2.

Mononuclear, predominantly CD3+ T-cell vasculitis affecting small-sized cerebral vessels (patient 1). (A, C, D, and E) Angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates exhibit a characteristic TVE pattern (note the similarity of the patterns in Fig. 1A, B, and E). (A) Sparsely distributed and relatively scant CD3+ cell infiltrates are present in the intervening neuropil of deep gray matter (thalamus). Note a single CD3+ T cell encroaching on the axon hillock of a large projection-type thalamic neuron (lower left field of the photomicrograph). (C, D, and E) Incremental gradations of angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates in cerebral small-sized vessels. (C) Scant perivascular (periadventitial) CD3+ T cells; intact vessel wall and endothelial cell lining. (D) Zonal (corona-like) distribution of CD3+ T cells along the circumference of the vessel wall (TVE). A CD3−, spindle-appearing endothelial cell is conspicuous on the luminal side and is encroached by CD3+ T cells. (E) Overt TVE infiltration by CD3+ T cells. Note two back-to-back PV monocytes/macrophages (cells with large vesicular nuclei). (B) Cluster of p24-positive monocytes/macrophages around a small intraparenchymal vein exhibiting less-prominent angiocentric infiltrates. ABC-immunoperoxidase was used for all panels; panels A and C to E were counterstained with H&E, and panel B was counterstained with methyl green. Original magnifications, ×400 (A and B) and ×1,000 (C to E).

One of these five patients (no. 1) exhibited a widespread and pronounced nonnecrotizing vasculitis, primarily affecting veins of all sizes. These lesions contained TVE mononuclear cell infiltrates which also extended into the endothelium (endothelitis) (Table 2; Fig. 1A, B, and E; Fig. 2A and C to E). Multifocal, recently superimposed-on subacute ischemic infarcts involving cortical, subcortical, and brain stem structures were present in the CNS of this patient. They exhibited features of liquefactive necrosis with resorption by massive accumulations of foamy macrophages.

A second patient (no. 2) showed, in addition to PV mononuclear cell infiltrates, fibrointimal thickening of the middle cerebral arteries (MCA) and anterior cerebral arteries (ACA) associated with two old infarcts in their corresponding territories. The larger one was a cortical cystic infarct with white matter extension involving the left frontal lateral convexity in the territorial distribution of the MCA, while the second was a smaller, lacunar-type infarction involving the deep hemispheric white matter in the border zone of the deep perforators of the MCA and ACA.

The cerebral infarcts demonstrated pathologically at postmortem were not readily apparent on clinical examination in either patient 1 or 2. Patient 1 (multiple, multifocal, recently superimposed-on subacute, principally subcortical infarctions) presented with an acute encephalopathy with brain stem signs, whereas patient 2 (bilateral, old or cavitary white matter infarcts) had spastic diparesis. The latter might have been associated with subclinical infarcts involving the deep periventricular cerebral white matter.

Cerebral vasculopathy was found in five of six patients (Table 2). Moderate to severe mineralization (calcification) of intraparenchymal blood vessels and perivascular spaces was present in the basal ganglia and hemispheric white matter of five of six patients (no. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). Two of the five children with pathological evidence of calcific vasculopathy were on antiretroviral treatment (patients 3 and 4) (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, the child with chronic markedly progressive encephalopathy (no. 3) had severe calcific vasculopathy.

Two patients (no. 3 and 5) (Table 2) exhibited HIV-1 encephalitis, which was defined as described in Materials and Methods. Only one of the two children with HIV-1 encephalitis (patient no. 3) was diagnosed with chronic markedly progressive encephalopathy. The second patient (no. 5) had a chronic static encephalopathy. There was no evidence of opportunistic infection(s) or malignancy in the CNS in any of the six patients.

Angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates.

PV mononuclear cell infiltrates in brain tissue specimens from five of six children with AIDS (no. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6) were composed of CD3+ T cells and equal or greater proportions of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages (Table 3; Fig. 1 to 3). The majority of CD3+ cells were also CD8+, as determined by immunohistochemical staining of adjacent tissue sections (Fig. 3).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of CD3+, CD8+, CD45RO+, and CD68+ cell infiltrates in HIV-1-associated CNS disease in children

| Patient no. | Angiocentric infiltrates

|

Infiltrates in brain neuropil

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+ | CD8+ | CD45RO+ | CD68+ | CD3+ | CD8+ | CD45RO+ | CD68+ | |

| 1 | ++++ (TVE > PV)a | ++++ (TVE > PV) | +++ (PV > TVE)b | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++++e |

| 2 | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV)c | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV) | − | − | + | +++e |

| 3 | − | − | − | + (PV) | − | − | − | ++f |

| 4 | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV) | − | − | + | ++f |

| 5 | ++ (PV) | ++ (PV) | NDd | ++ (PV) | − | − | ND | ++f |

| 6 | + (PV) | + (PV) | ND | + (PV) | − | − | ND | ++f |

TVE > PV, TVE is predominant compared to PV infiltrates. Blood vessel walls and endothelia comprise predominantly CD3+ CD8+ T cells, particularly on the endothelial (adluminal) side, but also contain CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. The majority of the CD3+ CD8+ T cells are also CD45RO+. The contiguous perivascular spaces are packed with CD68+ monocytes/macrophages admixed with various proportions (equal or lesser numbers) of CD3+ CD8+ T cells.

PV > TVE, predominantly PV distribution of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages in angiocentric infiltrates. However, CD68+ monocytes/macrophages also participate in the TVE infiltrates, together with CD3+ CD8+ T cells.

PV, solely perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrates consisting of CD3+ CD8+ T cells and CD68+ monocytes/macrophages, as described in the text.

ND, not determined.

CD68 localization in monocytes/macrophages.

CD68 localization in microglia (rod-shaped, ramified, parenchymal stellate cells).

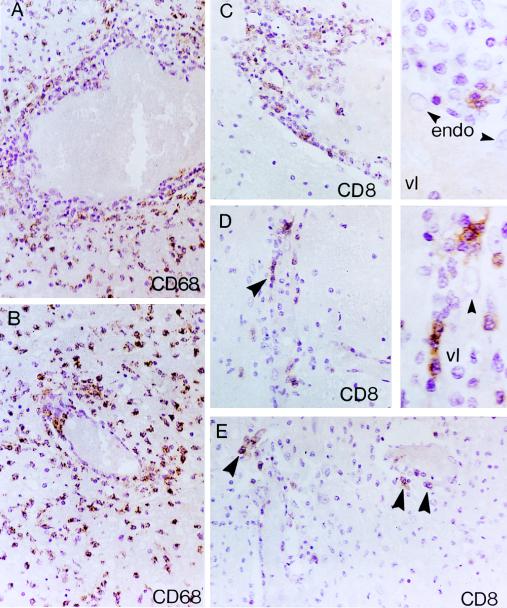

FIG. 3.

Patient no. 1 (A and B) Distribution of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages in TVE involving medium-sized (A) and small-sized (B) cerebral vessels. (A) A zonal angiocentric pattern of inflammation characterized by a rim of CD68− TVE and, to a lesser degree, PV lymphocytic infiltrates, surrounded by an outer zone consisting predominantly of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. (B) A small vessel exhibiting focal TVE involvement by CD68+ monocytes/macrophages. The intervening brain neuropil (A and B) is dominated by heavy accumulations of CD68+ cells. (C to E) Distribution of CD8+ lymphocytes in TVE involving medium-sized (C) and small-sized (D and E) vessels. (C) Distribution of CD8+ cells in TVE and PV. Note the distinct predilection of CD8+ lymphocytes for the inner portions of TVE in juxtaposition to the endothelial lining (arrowheads) (see also right insets in panels C and D). Also note the paucity of CD8+ T cells in the intervening neuropil. endo, endothelial cells; vl, vessel lumen. ABC immunoperoxidase and counterstaining with H&E were used for all panels. Original magnifications, ×400 (A to D) and ×1,000 (insets in panels C and D).

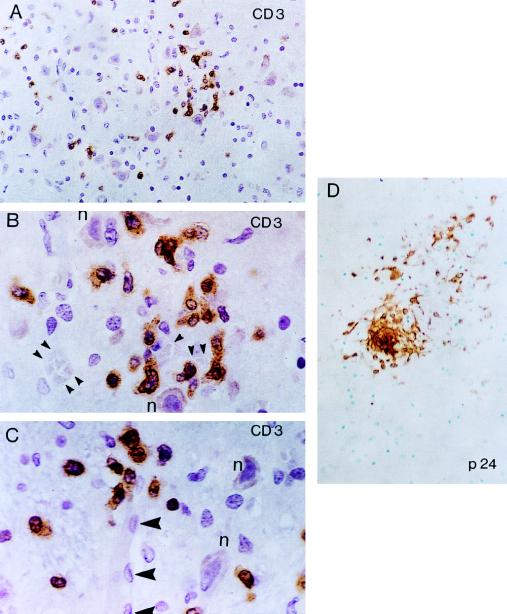

TVE mononuclear-cell infiltrates were evident in patient 1 and consisted predominantly of CD3+ T cells (Fig. 1A, B, and E; Fig. 2A and C to E) and lesser or, in certain vessels, approximately equal proportions of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 3A and B). CD3+ T-cell TVE infiltrates exhibited a characteristic zonal distribution. The majority of the CD3+ T cells were also CD8+ (Fig. 3C to E). There was a clear preponderance of CD3+ CD8+ infiltrating T cells on the endothelial (adluminal) side of TVE (Fig. 1A, B, and E; Fig. 2A and C to E; Fig. 3C to E). The adjacent perivascular spaces were packed with cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage (CD68+) and equal or, in certain foci, lesser proportions of CD3+ CD8+ T cells similar to those described above for the exclusively PV infiltrates. The intervening brain neuropil was dominated by CD68+ monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 3A and B), microglia (CD68+), and reactive astrocytes and contained only sparsely distributed and relatively scant CD3+ CD8+ infiltrates (Fig. 4A). The latter were consistently found in areas neighboring florid vasculitis. In areas of parenchymal infiltration, CD3+ T cells were found close to CNS microvessels (Fig. 4B and C). However, given the rich vascularity of the brain, particularly the deep gray matter (e.g., thalamus), a perivascular origin of CD3+ T cells may be difficult to prove by light microscopy and immunohistochemical staining, at least with respect to microvessels. By contrast, in lesions featuring a focal, solely perivascular pattern of CD3+ infiltrates, i.e., without TVE infiltrates, such as in patients 2, 4, 5, and 6, there was a paucity or complete lack of CD3+ cells in the neuropil, aside from certain rare CD3+ T lymphocytes found amid microglial nodules (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Patient no. 1. (A) Focal, scant CD3+ T-cell parenchymal infiltrates are demonstrated in the thalamus. (B and C) At a higher magnification, note the relationship of these infiltrates to cerebral microvessels (arrowheads). Note the relationship of CD3+ T cells to the nearby neuronal cell bodies (n). (D) Localization of HIV-1 p24 core protein in a microglial nodule from a patient with neuropathological changes consistent with HIV-1 encephalitis. ABC-immunoperoxidase was used for all panels; panels A to C were counterstained with H&E, and panel B was counterstained with methyl green. Original magnifications, ×400 (A and D) and ×1,000 (B and C).

CD45RO+ cells were examined in four patients (no. 1, 2, 3, and 4) (Table 3), and their numbers were found to be in the same range as those of CD3+ CD8+ T cells. The topographic distribution of CD45RO+ cells in brain tissue sections from these patients mirrored that of the CD3+ CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Localization of p24 was observed in two main settings: (i) perivascular monocytes/macrophages in areas of intense vasculitis, particularly involving veins (Fig. 1B and C and 2B); and (ii) in microglial nodules from areas consistent with HIV-1 encephalitis (Fig. 4D). No immunoreactivity was detected with anti-CMV or anti-EBV antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Perivascular and transmural mononuclear cell infiltrates found in the absence of opportunistic infections or malignancy in the CNS of HIV-1-infected children were comprised primarily of CD3+ CD8+ T cells and, to a lesser extent, CD45RO+ cells. CD45RO is a late activation antigen expressed on primed T cells that are becoming CD45RO+ CD45RA− as a result of antigenic stimulation. Virgin T lymphocytes are CD45RO− (2). Certain non-T cells are also CD45RA+ (2).

Studies of brain tissues from adult asymptomatic HIV-1-infected individuals who died accidentally of unnatural causes (31–33, 36), including an individual who was iatrogenically infected (15), revealed that the CNS is infected by HIV-1 at the time of primary infection (for reviews, see references 15 and 33). This results in an inflammatory response in the CNS, characterized by extensive mononuclear-cell infiltrates comprised primarily of T cells and, to a lesser degree, of monocytes/macrophages. Vasculitis, leptomeningitis, activation of microglial cells in brain parenchyma, increased expression of HLA class II, and production of cytokines have all been documented in the CNS of these patients (for a review, see reference 33). However, the mechanism of entry of the virus into the CNS remains to be elucidated. A commonly proposed mechanism involves the “Trojan horse” hypothesis (1, 20, 52a, 61), which theorizes that monocytes, latently infected by HIV-1, carry the virus into the CNS by crossing the blood-brain barrier and infiltrating the perivascular space, and these cells mature into macrophages and produce virus in the CNS. Lackner suggested that T cells may also be involved in initial HIV-1 infection of the CNS (44). It has been reported that T-cell lymphoblasts can enter the CNS of naive rats randomly and transiently and, in the absence of antigenic stimulation, exit in 1 or 2 days (37). Along these lines, migration of CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals across endothelial-cell monolayers was significantly increased compared to that of CD4+ T cells from normal donors (7). Chemokines (47), cytokines (25), and HIV-1 proteins (Tat and gp160) (9, 16, 48) may facilitate the entry of the virus across the blood-brain barrier. Similar results of early infection of the CNS have been observed with simian and feline immunodeficiency viruses (12, 43).

Our studies suggest that in TVE, T cells transverse the entire thickness of the vessel wall and are present in the intima. The underlying mechanisms, as well as the question of concomitant endothelial injury, remain to be investigated.

In contrast to the findings of angiocentric CNS infiltrates in HIV-1-infected children (13, 17, 59, 64, 65, 68), vasculitis and leptomeningitis are generally no longer found in the CNS of adult AIDS patients with late-stage disease (30, 33). However, “sequelae of transient cerebral vasculitis and leptomeningitis” (33) are evident (30–33). Fibrous thickening and mineralization of the walls of blood vessels have been reported in the CNS of these patients, consistent with a healing process after vascular injury (30–33). It appears that in adult AIDS patients the inflammatory reaction and the mononuclear cell infiltrates are transient (30–33). In contrast, in a substantial proportion of HIV-1-infected children, perivascular and, in certain cases, transmural infiltrates are found in the CNS at autopsy (13, 17, 59, 64, 65, 68). In this study, HIV-1-associated CNS vasculitis was observed in five of six patients, none of whom was preselected for the presence of vascular inflammation. This incidence is higher than that reported in the literature (64, 65, 68), i.e., approximately 30% of pediatric patients. However, the incidence of such lesions in children with AIDS may be underestimated, since there have been no studies that specifically address the incidence of angiocentric lymphocytic infiltrates in the context of TVE and/or PV patterns in the pediatric AIDS population. The reasons for the differences between pediatric and adult patients are not known and may include the relative immaturity of the immune system at the time of infection or significant changes in the development of the T-cell repertoire in the thymus due to virus-induced thymic injury in utero (42a).

Vasculitis, characterized by mononuclear-cell infiltration of blood vessels, is a systemic disease that affects multiple organs, including the CNS (26, 28, 64), peripheral nerves, skeletal muscle, and skin, in HIV-1-infected children and adults (11, 24, 27, 28, 45, 77). Angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates of the CNS of HIV-1-infected children closely resemble the benign lymphocytic angiitis variant of the T-cell syndrome designated angiocentric immunoproliferative lesions (28, 39). The latter, together with the related diffuse infiltrative CD8 lymphocytosis syndrome (3, 11, 38), is common in adult HIV-1 patients (3, 11). There are histological and phenotypic similarities between the HIV-1-associated angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates in the CNS of HIV-1-infected children and those found in the CNS of adult patients with AIDS. In the present study, the localization of p24-positive perivascular monocytes is similar to the p24-positive lymphohistiocytic cells and endothelial cells in CNS lymphomatoid granulomatosis (3), in which p24 localization was confined to areas of vasculitis but was absent from cerebral blood vessels that were devoid of inflammatory infiltrates.

Little is known about vascular inflammation and the role of T cells in CNS vascular/endothelial injury in HIV-1-infected individuals. Gray et al. suggested that the perivascular T-cell infiltrates are not due to an immune response to a productive HIV-1 infection, because their presence is not associated with the appearance of multinucleated giant cells and because the viral load in the CNS is very low during the inflammatory response (33). This suggests that the basis of the T-cell response may be autoimmune. It has been proposed that the extensive immune dysregulation that takes place during the initial and intermediate phases of HIV-1 infection may lead to autoimmune conditions (62). However, autoimmune mechanisms may be a more frequent cause of peripheral nervous system neuropathies than CNS disease (62). These neuropathies are commonly observed in HIV-1-infected patients (69) and may be related to autoimmune vasculitis (45).

Alternatively, these CNS-infiltrating lymphocytes may represent an anti-HIV-1 response that is responsible, at least in part, for containing viral infection. However, it is unclear whether HIV-1 might trigger vasculitis and, in particular, what antigenic determinants are recognized by infiltrating CD3+ T cells. Cerebrovascular endothelial cells can be infected by HIV-1, and this occurs through a CD4/galactosylceramide-independent mechanism (4, 49–51, 60, 75), although viral replication may be minimal (60). However, certain HIV-1 strains have been reported to selectively infect brain endothelial cells (50). We did not detect p24 staining in endothelial cells even in lesions with florid transmural infiltrates, in agreement with the report of Poland et al., who did not find p24 antigen or transcripts in human brain-derived endothelial cells infected with HIV-1 in vitro (60). HLA class I expression on endothelial cells, macrophages, and oligodendroglia and HLA class II expression on macrophages, oligodendroglia, and occasional endothelial cells are upregulated in patients with HIV-1 encephalitis (1). HLA class II expressing cerebrovascular endothelial cells can effectively present antigen to T cells (23). Activated endothelial cells may present viral peptides, in the context of HLA class I or class II, to T cells and may trigger a T-cell response targetted against blood vessels, particularly during the initial phase(s) of the infection. Microglia, monocytes/macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells are infected with HIV-1 (for a review, see reference 21). Neurons in adults are thought to be spared of HIV-1 infection (35, 66), although HIV-1 occasionally is found in pyramidal neurons (53) and can infect fetal neurons (74). Restricted replication of HIV-1 has been also detected in astrocytes (67, 71).

Recently, it was reported that transgenic mice carrying a replication-defective HIV-1 provirus with selective deletion of the gag, pol, and env genes developed extensive vasculopathy associated with the proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMC) of blood vessels in several organs, including the brain, leading to thickening of the intima and media (70). The hypertrophic vessel walls were infiltrated by T cells of unknown specificity and some plasma cells, while the endothelium was not affected. It is not known whether SMC can be infected with HIV-1 or whether HIV-1 gene expression can be detected in SMC of HIV-1-infected patients. It has been suggested that brain microvascular SMC treated with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) can present antigen to CD4+ T cells (22). On the other hand, T cells infiltrating blood vessels, either in HIV-1-transgenic mice or in HIV-1-infected patients, may be autoimmune, that is, specific for host antigens that may be expressed by SMC or endothelial cells. HIV-1-specific T cells, due to molecular mimicry, may recognize as viral a self-determinant cross-reacting with the virus. Molecular mimicry is defined as the presence of common epitopes on microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, etc.) and host proteins (54, 55, 76) and may result in the development of autoimmune disease. Molecular mimicry appears to play a role in several autoimmune diseases (54). Extensive molecular mimicry has been observed between a number of HIV-1 and host proteins (8, 18, 29).

HIV-1 induces strong HLA class I-restricted cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses which are mostly mediated by CD8+ T cells (for reviews, see references 42 and 57). CTL play an important role in controlling HIV-1 infection; and their appearance correlates well with the decline of viremia, while their loss coincides with disease progression (reviewed in references 42 and 57). T cells recognize several peptides derived from structural (e.g., Env, Gag, and Pol) or regulatory (e.g., Nef and Tat) HIV-1 antigens in association with either MHC class I (reviewed in references 42 and 57) or class II (42, 73) and are clonally expanded during primary HIV-1 infection. However, these CTL clones disappear later, perhaps due to clonal exhaustion (52, 58), whereas the viral epitope is still present. CTL control HIV-1 either by lysing HIV-1-infected cells (10) or by noncytolytic suppression of HIV-1 replication (5, 10, 14, 46) via chemokines (14) or cytokines (5). The role of CTL in CNS pathology of HIV-1 infection is unclear. HIV-1-specific CTL have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-1-infected patients (40, 63), produce tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interleukin-4 (41) and may contribute to the elevated levels of TNF-α (72) and IFN-γ (34) found in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Whether CTL lyse CNS cells either directly and/or indirectly, through the production of cytokines, is not clear at present.

In conclusion, we report here the presence of angiocentric CD3+ T-cell infiltrates in the CNS of HIV-1-infected children. These T cells may be responsible, at least in part, for endothelial cell injury (78) and for the opening of the blood-brain barrier in HIV-1-infected children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Eleanor Naylor Dana Charitable Trust to E.L.O.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achim C L, Morey M, Wiley C A. Expression of major histocompatibility complex and HIV antigens within the brain of AIDS patients. AIDS. 1991;5:535–541. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbar A N, Terry L, Timmus A, Beverly P C, Janossy G. Loss of CD45R and gain of UCHL1 reactivity is a feature of primed T cells. J Immunol. 1988;140:2171–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders K H, Latta H, Chang B S, Tomizasu V, Quddusi A S, Vinters H V. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis and malignant lymphoma of the central nervous system in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:326–334. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagasra O, Lavi E, Bobroski L, Khalili K, Pestaner J P, Tawadros R, Pomerantz R J. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 in the central nervous system of infected individuals: identification by the combination of in situ polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. AIDS. 1996;10:573–585. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baier M, Werner A, Bannert N, Metzner K, Rurth R. HIV suppression by interleukin-16. Nature. 1995;378:563. doi: 10.1038/378563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belman A L, Ultmann M H, Horoupian D, Novick B, Spiro A J, Rubinstein A, Kurtzberg D, Cone-Wesson B. Neurological complications in infants and children with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:560–566. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birdsall H H, Trial J, Lin H J, Green D M, Sorrentino G W, Siwak E B, Dejong A L, Rossen R D. Transendothelial migration of lymphocytes from HIV-1-infected donors—a mechanism for extravascular dissemination of HIV-1. J Immunol. 1997;158:5968–5977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracci L, Ballas S K, Spreafico A, Neri P. Molecular mimicry between the rabies virus glycoprotein and human immunodeficiency virus-1 gp120-cross-reacting antibodies induced by rabies vaccination. Blood. 1997;90:3623–3628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bragardo M, Buonfiglio D, Feito M J, Bonissoni S, Redoglia V, Rojo J M, Ballester S, Portoles P, Garbarino G, Malavasi F, Dianzani U. Modulation of lymphocyte interaction with endothelium and homing by HIV-1 gp120. J Immunol. 1997;159:1619–1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buseyne F, Fevrier M, Garcia S, Goudeon M L, Riviere Y. Dual function of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clone: inhibition of HIV replication by noncytolytic mechanisms and lysis of HIV-infected CD4+ cells. Virology. 1996;225:248–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese L H, Estes M, Yen-Lieberman B, Proffitt M R, Tubbs R, Fishleder A J, Levin K H. Systemic vasculitis in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:569–576. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakrabarti L, Hutrel M, Maire M A, Vazeux R, Dormont D, Montagnier L, Hurtrel B. Early viral replication in the brain of SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:1273–1280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho E S, Sharer L R, Peress N S, Little B. Intimal proliferation of leptomeningeal arteries and brain infarcts in patients with AIDS. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1987;46:385. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factor produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis L, Hjelle B, Miller V E, Palmer D L, Llewellyn A L, Merlin T L, Young S A, Mills R G, Wachsman W. Early brain invasion in iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology. 1992;42:1736–1739. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhawan S, Puri R K, Kumar A, Duplan H, Masson J M, Aggarwal B B. HIV-1 tat protein induces the cell surface expression of endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in human endothelial cells. Blood. 1997;90:1535–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson, D. W., A. L. Belman, Y. D. Park, C. Wiley, D. S. Horoupian, J. Llena, K. Kure, W. D. Lyman, R. Morecki, and S. Mitsudo. 1989. Central nervous system pathology in pediatric AIDS: an autopsy study. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 97(Suppl. 8):40–57. [PubMed]

- 18.Eddleston M, de La Torre J C, Xu J Y, Dorfman N, Notkins A, Zolla-Pazner S, Oldstone M B. Molecular mimicry accompanying HIV-1 infection: human monoclonal antibodies that bind to gp41 and to astrocytes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:939–944. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein L G, Sharer L R, Oleske J M, Connor E M, Goudsmit J, Bagdon L, Robert-Guroff M, Koenigsberger M R. Neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in children. Pediatrics. 1986;78:678–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein L G, Gendelman H E. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of the central nervous system: pathogenetic mechanisms. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:429–436. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein L G, Gendelman H E, Lipton S A. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 neuropathogenesis. In: Berger J R, Levy R M, editors. AIDS and the nervous system. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabry Z, Waldschmidt M M, VanDyk L, Moore S A, Hart M N. Activation of CD4+ lymphocytes by syngeneic brain microvascular smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:1099–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabry Z, Hart M N. Antigen presentation at the cerebral microvasculature. In: Pardridge W M, editor. The blood-brain barrier: cellular and molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Raven; 1993. pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farthing C F, Staughton R C, Roland-Payne C M E. Skin disease in homosexual patients with acquired immunodeficiency virus (HTLV III) disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1985.tb02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiala M, Looney D J, Stins M, Way D D, Zhang L, Gan X H, Chiapelli F, Schweitzer E S, Shapsak P, Weinand M, Graves M C, Witte M, Kim K S. TNF-α opens a paracellular route for HIV-1 invasion across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med. 1997;3:553–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank Y, Lim W, Kahn E, Farmer P, Gorey M, Pahwa S. Multiple ischemic infarcts in a child with AIDS, varicella zoster infection, and cerebral vasculitis. Pediatr Neurol. 1989;5:64–67. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(89)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gherardi R, Lebargy F, Gaulard P, Mhiri C, Bernaudin J F, Gray F. Necrotizing vasculitis and HIV replication in peripheral nerves. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:685–686. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gherardi R, Belec L, Mhiri C, Gray F, Lescs M-C, Sobel A, Gullevin L, Wechsler J. The spectrum of vasculitis in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. A clinicopathologic evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1164–1174. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golding H, Shearer G M, Hillman K, Lucas P, Manischewitz J, Zajac R A, Clerici M, Gress R E, Boswell R N, Golding B. Common epitope in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) I-GP41 and HLA class II elicits immunosuppressive autoantibodies capable of contributing to immune dysfunction in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:1430–1435. doi: 10.1172/JCI114034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray F, Gherardi R, Keohane C, Favolini M, Sobel A, Poirier J. Pathology of the central nervous system in 40 cases of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1988;14:365–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1988.tb01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray F, Lescs M-C, Keohane C, Paraire F, Marc B, Durogon M, Gherardi R. Early brain changes in HIV infection: neuropathological study of 11 HIV seropositive, non-AIDS cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:177–185. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray F, Hurtrel M, Hurtrel B. Early central nervous system changes in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1993;19:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray F, Scaravilli F, Everall I, Chretien F, An S, Boche D, Adle-Biassette H, Wingertsmann L, Durigon M, Hurtel B, Chiodi F, Bell J, Lantos P. Neuropathology of early HIV-1 infection. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffin D, McArthur J, Comblath D. Neopterin and interferon-gamma in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV-associated neurologic disease. Neurology. 1991;41:69–74. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harouse J M, Kunsch C, Hartle H T, Laughlin M A, Hoxie J A, Wigdahl B, Gonzalez-Scarano F. CD4-independent infection of human neural cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1989;63:2527–2533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2527-2533.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassine D, Gray F, Chekroun R, Chretien F, Marc B, Durigon M, Schouman-Claeys E. Early brain changes in HIV infection. Postmortem MRI findings and pathological correlation in asymptomatic HIV seropositive non-AIDS cases. J Neuroradiol. 1995;22:148–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hickey W F, Hsu B L, Kimura H. T-lymphocyte entry into the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 1991;28:254–260. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490280213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itescu S, Brancato L J, Buxbaum J, Gregersen P K, Rizk C C, Scott-Croxson T, Solomon G E, Winchester R. A diffuse CD8 lymphocytosis syndrome in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: a host immune response associated with HLA-DR5. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:3–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaffe E S. Pathologic and clinical spectrum of post-thymic T-cell malignancies. Cancer Invest. 1984;2:413–424. doi: 10.3109/07357908409040316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jassoy C, Johnson R P, Navia B A, Worth J, Walker B D. Detection of a vigorous HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in cerebrospinal fluid from infected persons with AIDS dementia complex. J Immunol. 1992;149:3113–3119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jassoy C, Harrer T, Rosenthal T, Navia B A, Worth J, Johnson R P, Walker B D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes release gamma interferon, tumor necrosis alpha (TNF-α), and TNF-β when they encounter their target antigens. J Virol. 1993;67:2844–2852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2844-2852.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson R P, Walker B D. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus infection: responses to structural proteins. Curr Top Microb Immunol. 1994;189:35–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78530-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.Katsetos, C. D., et al. Unpublished data.

- 43.Lackner A A, Vogel P, Ramos R A, Kluge J D, Marthas M. Early events in tissues during infection with pathogenic (SIVmac239) and nonpathogenic (SIVmac1A11) molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:428–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lackner A A. Neuroinvasion and neuropathogenesis of HIV infection. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:12–14. . (editorial.) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipkin W I, Parry G, Kiprov D, Abrams D. Inflammatory neuropathy in homosexual men with lymphadenopathy. Neurology. 1985;35:1479–1483. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.10.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackewicz C E, Yang L C, Lifson J D, Levy J A. Non-cytolytic CD8 T cell anti-HIV responses in primary HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1994;344:1671–1673. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller M D, Krangel M S. Biology and biochemistry of the chemokines: a family of chemotactic and inflammatory cytokines. Crit Rev Immunol. 1992;12:17–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitola S, Sozzani S, Luini W, Primo L, Borsatti A, Weich H, Bussolino F. Tat-human immunodeficiency virus-1 induces human monocyte chemotaxis by activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1. Blood. 1997;90:1365–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moses A V, Bloom F E, Pauza C D, Nelson J A. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human brain capillary endothelial cells occurs via a CD4/galactosylceramide-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10474–10478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moses A V, Nelson J A. HIV infection of human capillary endothelial cells—implications for AIDS dementia. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(06)80262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moses A V, Stenglein S G, Strussenberg J G, Wehrly K, Chesebro B, Nelson J A. Sequences regulating tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 for brain capillary endothelial cells map to a unique region on the viral genome. J Virol. 1996;70:3401–3406. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3401-3406.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moss P A, Rowland-Jones S L, Frodsham P M, McAdam S, Giangrande P, McMichael A J, Bell J I. Persistent high frequency of human immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T cells in peripheral blood of infected donors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5773–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52a.Nottet H S, Persidsky Y, Sasseville V G, Nukuna A N, Bock P, Zhai Q H, Sharer L R, McComb R D, Swindells S, Soderland C, Gendelman H E. Mechanisms for the transendothelial migration of HIV-1-infected monocytes into brain. J Immunol. 1996;156:1284–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nuovo G J, Gallery F, MacConnell P, Braun A. In situ detection of polymerase chain reaction-amplified HIV-1 nucleic acids and tumor necrosis factor-alpha RNA in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:659–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oldstone M B. Molecular mimicry and autoimmune disease. Cell. 1987;50:819–820. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oleszak E L, Leibowitz J. Immunoglobulin Fc binding activity is associated with the mouse hepatitis virus E2 peplomer protein. Virology. 1990;176:70–80. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90231-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oleszak E L, Katsetos C D, Kuzmak J, Varadhachary A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis infection. J Virol. 1997;71:3228–3235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3228-3235.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pantaleo G, Fauci A S. Immunopathogenesis of HIV infection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:825–854. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pantaleo G, Soydens H, Demarest J F, Vaccarezza M, Graziosi C, Paolucci S, Daucher M B, Cohen O J, Denis F, Biddison W E, Sekaly R P, Fauci A S. Evidence of rapid disappearance of initially expanded HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell clones during primary HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9848–9853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park Y D, Belman A L, Kim T-S, Kure K, Liena J F, Lantos G, Bernstein L, Dickson D W. Stroke in pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:303–311. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poland S D, Rice G P, Dekaban G A. HIV-1 infection of human brain-derived microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. J AIDS Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:437–445. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Power C, McArthur J C, Johnson R T, Griffin D E, Glass J D, Perryman S, Chesebro B. Demented and nondemented patients with AIDS differ in brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope sequences. J Virol. 1994;68:4643–4649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4643-4649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Price R W. Neurological complications of HIV infection. Lancet. 1996;348:445–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)11035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sethi K K, Naher H, Stroehmann I. Phenotypic heterogeneity of cerebrospinal fluid derived HIV-specific and HLA-restricted cytotoxic T cell clones. Nature. 1988;335:178–181. doi: 10.1038/335178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharer L R, Epstein L G, Cho E-S, Joshi V V, Meyenhofer M F, Kankin L F, Petito C K. Pathologic features of AIDS encephalopathy in children: evidence for LAV/HTLV-III infection of brain. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharer L R, Cho E S. Neuropathology of HIV infection: adults versus children. Progr AIDS Pathol. 1989;1:131–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharer L R, Saito Y, Epstein L G, Blumberg B M. Detection of HIV-1 DNA in pediatric AIDS brain tissue by two-step ISPCR. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4:283–285. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(06)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharer L R, Saito Y, Da Cunha A, Ung P C, Gelbard H A, Epstein L G, Blumberg B M. In situ amplification and detection of HIV-1 DNA in fixed pediatric AIDS brain tissue. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:614–617. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharer L R, Saito Y, Blumberg B M. Neuropathology of human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of the brain. In: Berger J R, Levy R M, editors. AIDS and the nervous system. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 461–471. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simpson D M, Olney R K. Peripheral neuropathies associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurol Clin. 1992;10:685–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tinkle B T, Ngo L, Luciw P A, Maciag T, Jay G. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated vasculopathy in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1997;71:4809–4814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4809-4814.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tornatore C, Chandra R, Berger J R, Major E O. HIV-1 infection of subcortical astrocytes in the pediatric central nervous system. Neurology. 1994;44:481–487. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tyor W R, Glass J, Griffin J, Becker P, McArthur J, Bezman L, Griffin D. Cytokine expression in the brain during acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:349–360. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wentworth P A, Steimer K S. Characterization of human CD4+ HIV-SF2 Nef-specific T cell clones for antigen processing and presentation requirements and for cytotoxic activity. Vaccine. 1994;12:885–894. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wigdahl B, Guyton R A, Sarin P S. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of the developing human nervous system. Virology. 1987;159:440–445. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiley C A, Schrier R D, Nelson J A, Lampert P W, Oldstone M B. Cellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus infection within the brains of acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7089–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wucherpfennig K W, Strominger J L. Molecular mimicry in T-cell mediated autoimmunity: viral peptides activate human T-cell clones specific for myelin basic protein. Cell. 1995;80:695–705. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yanker B A, Skolnik P R, Shoukimas G M, Gabuzda D H, Sobel R A, Ho D D. Cerebral granulomatous angiitis associated with isolation of human T lymphotropic virus type III from the central nervous system. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:362–364. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zietz C, Hotz B, Sturzl M, Rauch E, Penning R, Lohrs U. Aortic endothelium in HIV-1 infection: chronic injury, activation, and increased leukocyte adherence. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1887–1898. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]