Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the 9-year journey of a group of language and literacy researchers in establishing and cultivating Research–Practice Partnerships (RPPs). Those interested in incorporating implementation science frameworks in their research may benefit from reading our exploration into this type of work and our lessons learned.

Method:

We showcase how a group of researchers, who are committed to collaboration with school practitioners, navigated building and scaling RPPs within educational systems necessary for our long-term implementation work. We provide details and illustrative examples for three, distinct, mutually beneficial, and sustainable partnerships.

Results:

Three different practice organizations are represented: (1) a single metropolitan school, (2) a small metropolitan school district, and (3) a large metropolitan school district, highlighting specific priorities and needs depending on the type of practice organization. Each partnership has distinct research and practice goals related to improving language and literacy outcomes in children. We describe how the researchers assisted with meeting the partner practice organizations' goals and engaged in capacity building while producing rigorous scientific knowledge to inform clinical and educational practice. Additionally, we discuss how research priorities and strategies were pivoted in the past year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, illustrating our commitment to the partnerships and how to respond to challenges to guarantee long-term sustainability.

Conclusion:

By discussing three distinctive partnerships, we demonstrate the various ways researchers can approach RPPs and grow them into mutually beneficial collaborations and support implementation goals.

As discussed in the prologue of this clinical forum and other recent special issues or supplements, there is a great momentum in the field of communication sciences and disorders to close the research-to-practice gap, specifically through the incorporation of implementation science (Douglas et al., 2015; Goldstein & Olswang, 2017; Olswang & Goldstein, 2017; Olswang & Prelock, 2015). Evidence-based practices that are proven to be efficacious by researchers are only likely to be effective and sustainable in settings where implementation of these practices is explicitly targeted in a collaborative and focused way. The field of implementation science studies the strategies that facilitate the adoption of evidence-based practices into routine practice. Ideally, assessment and intervention research should include simultaneous or subsequent implementation science methods to identify the implementation practices that best meet the needs of the settings and practitioners. This requires researchers to engage in building equitable and sustainable research collaborations with key stakeholders. As such, this clinical focus article will specifically review one framework for creating collaborative research opportunities, that is, RPPs (Coburn et al., 2013). In this clinical focus article, we describe how we applied an RPP framework across diverse educational settings throughout the United States to successfully build collaborative relationships that have resulted in implementation science outcomes such as the development of infrastructures to support universal screening and promote early identification of students who may be at risk of language and literacy difficulties. Additionally, these partnerships have generated mutually beneficial joint research objectives that have led to ongoing federally and privately funded longitudinal and cross-sectional research studies.

RPPs Within Implementation Science

An important aspect of implementation science is the incorporation of relevant stakeholders, also referred to as “operational partners” by Bauer and Kirchner (2020). These operational partners can be found at multiple hierarchical levels within an organization and serve to contextualize and inform practice needs where change may occur (Huang et al., 2018; Proctor et al., 2009). The individual-level operational partner is the consumer or provider of evidence-based practices or practice innovations (e.g., interventions, assessments, and service delivery models). In the field of communication sciences and disorders, this would be the patient, client, student, family/caregiver, the individual speech-language pathologist (SLP) or teacher. The team-level operational partner would include the delivery system or practice setting of the evidence-based practice or practice innovation such as the clinic, hospital, or school. Lastly, the organizational level is the larger administrative system in which the team is situated to support and sustain the evidence-based practice or innovation for long-term implementation. Some organizational-level operational partners could be a large school district or health care network in which the team operates. Importantly, when conducting clinical research, inclusion of operational partners at all levels is ideal to best align researcher priorities and practitioner expectations and needs.

In implementation research, these stakeholder partners play critical and active roles where they assist with designing or implementing the study. This contrasts with more traditional clinical practice research where operational partners typically play more distal roles as either facilitators of the study or those observed in the study. In recognition of this key ingredient to successful dissemination and implementation efforts, several frameworks for initiating research partnerships with stakeholders at various levels have emerged. Huang et al. (2018) conducted a review to summarize frameworks and methodologies for development of partnerships, engagement, and collaboration strategies in dissemination and implementation research in health care. They report essentials for positive partnerships include a shared understanding, a community of trust, and operationalizing shared decision-making processes.

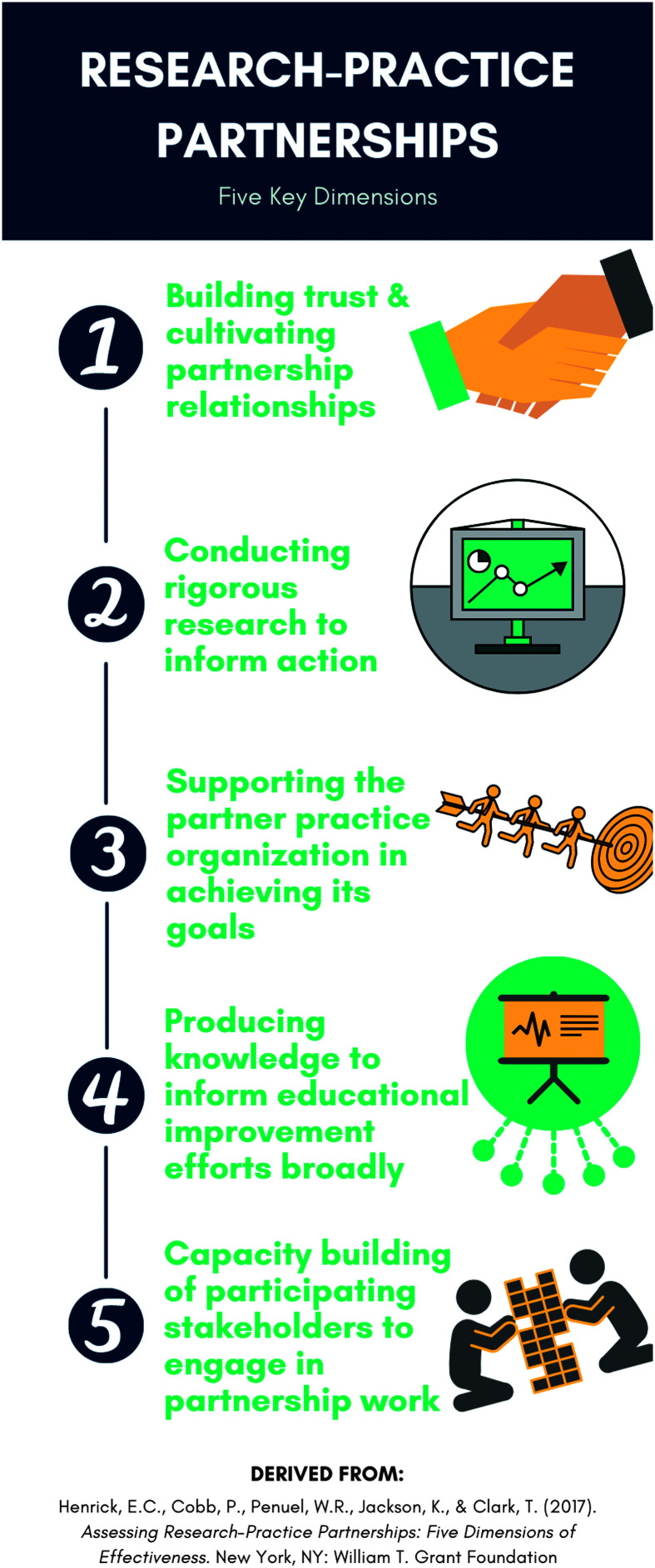

Understanding and improving “real-world” practice outcomes is foundational to implementation science, and RPPs help connect practice outcomes by engaging in stakeholder collaborations (Coburn et al., 2013; Tseng et al., 2017). Henrick et al. (2017) proposed five critical dimensions for successful partnership building that could be useful in assessing RPPs applied in education. These include but are not limited to (a) building trust and cultivating partnership relationships; (b) conducting rigorous research to inform action; (c) supporting the partner practice organization in achieving its goals; (d) producing knowledge that can inform educational improvement efforts more broadly; and (e) building the capacity of participating researchers, practitioners, practice organizations, and research organizations to engage in partnership work (Henrick et al., 2017; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The five key dimensions of Research–Practice Partnerships.

RPPs differ significantly from traditional collaborations between researchers and practice partners. Unlike traditional research collaborations that typically have a short-term focus to meet the narrow goals of a researcher, RPPs are (a) long term, (b) mutualistic, (c) intentional, (d) focus on problems of practice that include investigative solutions to improve outcomes, and (e) produce original analyses (Coburn et al., 2013). RPPs have primarily been applied in education and social work settings for university partnerships with educational and/or state agencies to address the associated challenges of practice (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Goldstein et al., 2019; Joubert, 2006).

Farrell et al. (2018) conducted a descriptive study on RPPs applied in the educational setting and funded by the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences to determine the potential benefits of such collaborations. Overall, nearly all the surveyed researchers and practitioners reported that their partnerships provided new ideas or frameworks for implementation and/or support by local policymakers. Moreover, these partnerships helped support the development of professional development, programming, and/or practices that were designed to fit the unique needs of the educational stakeholders. Additionally, practitioners reported that they (a) would participate in another RPP in the future, (b) shifted in their engagement with research, and (c) had a new and better understanding of how to incorporate research into their practice. Similarly, researchers reported that they (a) would also participate in RPPs in the future, (b) shifted in their understanding of the contextual factors faced by practitioners, and (c) increased their understanding of the value of including practitioner perspectives in the research process. These findings highlight the significant contribution of RPPs in implementation science. RPPs provided the opportunity for researchers to understand the real-world needs of practitioners, including the supports needed and barriers to be eliminated for successful implementation of evidence-based practices.

In addition to insights of the benefits of informal collaboration, Farrell et al. (2018) found that the overwhelming majority of RPPs (26 of 27 RPPs) had formalized infrastructure agreements, and these structures were often set up well before formal grant funding was secured. The commonly reported elements of these infrastructure agreements included data-sharing plans, memorandums of understanding, broad research agendas, and decision-making boards. These findings were reported to be useful for researchers and practitioners who, although interested in engaging in partnership research endeavors, were initially concerned that funding would need to be in place to launch and maintain successful collaborations. This formal agreement structure was related to Farrell et al.'s (2018) additional findings that the top two conditions for successful implementation of an RPP were mutual organizational interest and trust among the partners. These findings are in line with Coburn et al.'s (2013) findings that maintaining mutualism and building trust were necessary strategies for tackling challenges faced by RPPs to sustain them long term and essential for RPP success.

Overall, the findings of Coburn et al. (2013) and Farrell et al. (2018) provide insights to how RPPs can be useful frameworks for creating bidirectional relationships with mutual benefits such as knowledge transfer and improved implementation outcomes (as outlined in the study of Proctor et al., 2011). These partnerships can support improved understanding by both researchers and practitioners to help close both the research-to-practice and practice-to-research gaps.

Practical Considerations When Engaging in RPPs

Building sustainable RPPs can be challenging and requires considerable commitment from both researchers and practitioners. It is especially difficult when practitioners are practicing within organizational systems that have multiple stakeholders' interests to consider. Schools within the United States have federal and state regulations they must follow, as well as local school board and parent demands they must attend to. Funding for public education is tied to performance on high stakes assessments, and yet, practitioners are struggling to meet these demands due to a myriad of challenges with limited organizational support (Christian-Brandt et al., 2020). Exacerbating challenges include alarming rates of secondary trauma and burnout by educators and service providers alike due to working with children who are experiencing a high incidence of adverse childhood events such as food insecurity and domestic violence (Borntrager et al., 2012; Caringi et al., 2015; Hydon et al., 2015). Contrastively, researchers have academic institutional productivity demands to obtain extramural research funding and continuously publish rigorous scientific journal articles. These research output expectations can impede the desire to initiate and nurture time-consuming RPPs as they may not yield publishable scientific data for many years. Moreover, despite its potential for high clinical practice impact, there have historically been few funding mechanisms to support long-term RPP work.

Although we recognize that the constraints on practitioners and researchers can stifle interest and capacity to participate in RPPs, we believe that the promising outcomes of RPPs are worth the effort. We submit that taking risks to explore collaborative research frameworks such as RPPs can have high-impact payoffs for the students, families, and language and literacy providers and educators. Furthermore, committing to engage in collaborative research efforts, such as RPPs, provides opportunities for researchers to engage in implementation research. Like the examples discussed regarding school practitioner experiences and expectations, RPPs provide opportunities to directly examine various determinants acting as barriers to evidence-based practice implementation. Additionally, RPPs have the potential to improve practitioner participation in research in both traditional and implementation research.

A familiar lament of researchers is the difficulty in identifying and recruiting potential research participants (see Gul & Ali, 2010). For communication sciences and disorders researchers, we see similar challenges recruiting in our local communities despite tremendous efforts to send out recruitment notices via SLPs, educators, local schools, libraries, social media, and online parent groups. To those who are on the receiving end of these recruitment efforts, these calls for participation can feel overwhelming and misguided when they are struggling to meet their everyday demands. Yet, many do heed the call and will assist in recruitment or participate in research but then find themselves disappointed if there is no follow-up or maintenance of the relationship once the recruitment or study has commenced. This inability to maintain relationships could be the result of various demands on researchers as previously described or lack of support and infrastructures necessary for sustainability. Unfortunately, these researchers can be seen as “drive-by” researchers versus invested community partners and can color potential future collaborations or participation even if researchers want to create lasting collaborations.

Given the research supporting RPPs and the importance of implementation science for the integration and sustainability of evidence-based practice in the fields of education and communication sciences and disorders, the researchers in this clinical focus article chose to apply an RPP framework in their own educational research agendas. The following is a description of how the key elements of an RPP framework were applied across a variety of school settings over differing periods of time and most recently through a large-scale, multisite, and longitudinal educational research study across two states. We begin by describing the researchers and the three practice organizations that came together to create and nurture partnerships. We then discuss how we used the five dimensions of RPPs (Henrick et al., 2017) in building our partnerships, our successes and challenges, and the lessons we've learned along the way.

RPPs: A Look at Sustainable Examples

The Researchers

Our commitment to prioritizing partnering with educational systems is borne from the fact that all the lead researchers served as clinicians, conducted clinical practice research, and/or worked actively in schools prior to serving in their current university-level research positions. Although not a necessary component for successful RPPs, this group believes that our knowledge and recognition of school-based ecosystems and their relevant stakeholders was and continues to be a key guiding factor in our record of successful RPPs. As highlighted in the study of Douglas and Burshnic (2019) and any determinant framework used in implementation science (see Nilsen, 2015), a necessary and important component to implementation science is seeking out the practitioner's perspective to understand the unique contextual factors that support or hinder the uptake of clinical practice. Having experienced some of these contextual factors ourselves provides us unique insights that can lead to an understanding and respect of the practitioners' experience. We believe this respect and understanding has helped us in forming successful RPPs. By acknowledging the complex nature and demands on the key players of these systems, we build a greater capacity for science-based innovation to improve outcomes for children with language and literacy difficulties.

Identifying Practice Partners

When seeking operational partners to engage in an RPP, it is important to identify potential change agents. Change agents are an individual or group who facilitates and manages planned change or innovation brought about through a deliberate process intended to increase the likelihood of acceptance and implementation, and the potential benefit (Havelock, 1973). These change agents can be found at many levels in educational settings such as in administration or staff working with individuals, teams, or organizations. A knowledge broker is one type of change agent who promotes, facilitates, and supports knowledge translation efforts (Dobbins et al., 2019). One way in which a knowledge broker may function is to provide links between researchers and practitioners—essential in facilitating communication and knowledge sharing among the relevant stakeholders. In educational systems, knowledge brokers might be at any of the three organizational levels. One example of a knowledge broker might be a single SLP who attends a continuing education event and presents current empirical findings and resources related to curriculum or assessment that were shared at the event to their colleagues at a single school. Another example might be a school district administrator who sits on steering committees or task forces with university faculty for planning and rollout of state education legislation. Both examples illustrate how these individuals could be open to collaborations if approached by researchers.

When forming our RPPs, we first identified and contacted potential knowledge brokers at targeted practice organizations. Importantly, some RPPs are not formed to target a specific research question in mind; instead, they may have the shared goal to identify problems of practice and seek out and test potential solutions. In the examples that follow, the researchers and practice organizations shared interest in improving general and special education practices for children with language and literacy difficulties. Specifically, the practice organizations were seeking assistance with addressing new legal requirements around early identification and support of students with literacy disabilities such as developmental language disorder (DLD) and dyslexia. They deemed our research timely, relevant, and useful for their staff and students. This was important because, we, the researchers, seek to create partnerships that not only further our own research agendas but also address problems of practice and promote positive change in educational systems.

For our purposes, we sought knowledge brokers who were already serving in roles that assisted with cultivating a culture that valued evidence-based practice or facilitated capacity building in their teams or organizations. It is important to note, however, that not all contacts with knowledge brokers were successful. The main reason for this was that the priorities of the practice organization did not immediately align with those of the researchers. This is a valuable reminder that, although all educational systems in the United States aim to provide high-quality language and literacy instruction and intervention, not all schools may be interested in or have the capacity and support to engage with the specific curricular programs or interventions proposed by researchers. For this clinical focus article, we focus on three practice organizations we built RPPs with successfully.

The Practice Organizations

Each practice organization had unique needs and student populations that they served. They spanned two distinct regions of the United States, an expansive metropolitan region in New England, and a smaller metropolitan region serving the rural Northwest. The student populations across these practice organizations included the full spectrum of socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and language status. Teacher training was also varied in that one region required master's degrees for teaching certifications and the other only required a bachelor's degree. Overall, the practice organizations represented diverse populations and voiced distinct needs.

Although the start of these partnerships varied, all the partnerships we highlight in this clinical focus article engaged in current studies investigating long-term outcomes of young school-age children with and without DLD and/or dyslexia. The timing for the start of these studies was favorable for two main reasons. First, the Science of Reading movement (Defining Movement, 2021) has made great advances in promoting evidence-based practice in language and literacy, pushing school districts to improve their practices. Second, most states in the United States passed special laws that mandated early screening and support of students with learning disabilities such as dyslexia. These reasons contributed to the practice organizations' interest in our studies and how we could support their language and literacy practices.

Each practice organization resulted in a distinct partnership with different beginnings, unique requirements and commitments, variable levels of interaction, and potential long-term trajectories. Despite the varied engagements and objectives in all three partnerships, we chose to highlight these three because they all successfully met one specific objective, that is, the early identification of students who may be at risk of DLD and/or dyslexia. They did this by committing to participate in our ongoing large National Institute of Health (NIH) multisite grant where we administered researcher-developed language and literacy classroom-based screenings to all their kindergarten classrooms.

Although each operational partner discussed is at the organizational level, we chose to discuss these partnerships in chronological order, which also highlights that over time they have increased in size (e.g., from a single school to a large metropolitan school district). For many, the entry point for creating RPPs may be small, with a single school. Over time, with experience and alignment of priorities, RPPs can be expanded to include larger organizations and secured grant funding to support these collaborative efforts. Highlighting this will hopefully encourage researchers interested in pursuing this type of work to start where they are, even if it is reaching out to a single knowledge broker and getting that first meeting with leadership in a small organization. Furthermore, our RPPs illustrate how to start a research partnership and adjust expectations as needed to promote mutual trust, sustainability, and shared outcomes.

Practice Organization 1: A Public Elementary School

This operational partner was at the organizational level: a single pre-kindergarten through 5th grade elementary school (~4,000 enrolled students) in a small urban city (~20,000 population). Our initial knowledge broker was a veteran SLP at the school who was also an alumnus of one of our institutions and worked as a site clinical supervisor for SLP graduate clinicians. One of our researchers initiated a meeting with her and the school principal in 2012 to discuss mutual language and literacy interests and potential research collaborations. This SLP subsequently served as a liaison during the first research project at this school from 2013 to 2015. Our initial knowledge broker eventually retired, and we were able to sustain this RPP by continuing to build our relationship with the school leadership team, the principal and vice principal, who have been in these positions since the start of the RPP in 2012. Overall, this ongoing partnership has spanned 9 years and three different grant-funded (by the Institute of Education Sciences, the NIH, and a local accounting firm) research projects.

Practice Organization 2: A Small Metropolitan Public School District

This operational partner was also at the organizational level; however, this time, it was a school district for pre-kindergarten through the 12th grade (~9,200 enrolled students) in a small metropolitan city (~70,000 population). Our initial knowledge broker was a district administrator, with SLP experience, whose oversight included the elementary school special education branch of the district. Starting in 2016, we initiated meeting on a regular basis (approximately 1 time each semester) over 2 years to discuss the needs of the school district and areas of mutual concern. Over the course of 2018, additional knowledge brokers, the district lead SLP and district special education director, were added to the conversations and have continued as our initial knowledge broker retired. Overall, this ongoing partnership has been thriving for 5 years and has resulted in collaboration on a large, NIH-funded research project.

Practice Organization 3: A Large Metropolitan Public School District

Most recently, in 2018, we have formed a partnership with a large metropolitan school district (~95,000 enrolled students) in a large urban city (~185,000 population) to improve educational practices for children with language and literacy difficulties. Our initial knowledge broker was a district administrator who attended a presentation given by one of our researchers at a local conference and initiated the partnership by putting us in touch with district leaders who were interested in forming a partnership with experts in language and literacy. The connection was timely for both the district and the researchers as we had just been awarded a large federal grant and were looking for additional school partners to conduct research on long-term outcomes in children with DLD and/or dyslexia, and the district was seeking expert support for the new state mandate on dyslexia screening. Thus far, this partnership has been ongoing for 3 years, and we have worked collaboratively on one large, NIH-funded research project and have begun a second NIH-funded research project.

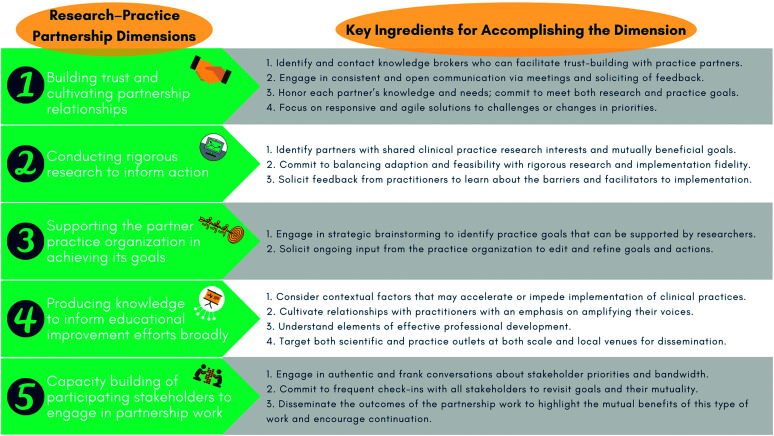

Assessing Partnerships Using the Five Dimensions of Effective RPPs

Based on the needs of these operational partners, our paths for each partnership have looked different, yet throughout, these partnerships have aligned with the five dimensions of effective RPPs proposed by Henrick et al. (2017) and shown in Figure 1. These dimensions can guide researchers and practitioners in their relationship building and collaboration. In this section, we unpack each dimension, summarizing key ingredients we have identified for each (see Figure 2) and providing exemplars from our three RPPs to illustrate how these dimensions can be achieved and how they might look different depending on the partnership.

Figure 2.

Key ingredients for accomplishing the Research–Practice Partnership dimensions.

1. Building Trust & Cultivating Partnership Relationships

Repeatedly, it has been reported that building and maintaining trust between partners is a key indicator of successful partnerships. Mutual respect, effective communication, and a willingness to adapt are integral to building trust. In each of our RPPs, a trusted member of the organization was identified and helped us establish trust within the organization and its leaders. For example, with the first practice organization, our initial contact was to the school's SLP who was an alumnus of one of our academic institutions and a leader in the school. For two of our practice organizations, we initially and strategically reached out to stakeholders who were familiar with the scope of practice of SLPs and potentially interested in discussing how to improve language and literacy outcomes for students. We hoped this common understanding and shared interest would promote relationship-building with these potential knowledge brokers and, in turn, increase our credibility when they facilitated meetings with school and district leadership. With the third practice organization, initial connections were made due to our outreach and dissemination efforts we routinely engage in. Presenting our research at local conferences provides opportunities to share our expertise and meet practitioners who are interested in our work. Once we were able to establish mutual trust and understanding of our goals, this knowledge broker facilitated meetings with district leaders. Overall, it was important to focus on building trust and strong relationships among all team members at the outset for each of our partnerships regardless of the initial practitioner connection.

The goals and priorities of each practice organization also influence the cultivation of the relationship. With the first practice organization, the goal of supporting students in their language and literacy development has remained over the years, but the focus on specific priorities in support of this goal has pivoted as necessary throughout our partnership. Through open and frequent communication, we have established trust within this partnership to support and meet shifting research and practice goals. Most recently, we have shifted to providing supplemental language comprehension interventions to second graders because the practitioners felt they were seeing positive outcomes in their decoding instruction but needed targeted support to improve comprehension outcomes. For Practice Organization 2, we began by meeting regularly to discuss needs leading to the formation of a panel of district representatives who could meet to outline plans and goals over the long term. However, after several months of meeting and planning language and literacy intervention trainings and potential research projects, our priorities had to quickly shift to meet the immediate district need of assisting with universal dyslexia screening due to the passing of state legislation. This was not a specific research goal for us but could easily be incorporated into a recent NIH-funded research project on early identification of children with DLD and/or dyslexia. With Practice Organization 3, the priorities of the practice organization (i.e., assistance with dyslexia screening) prompted their reaching out to us at a conference. Their needs led to establishing the relationship quickly, but trust-building efforts such as solicitation of feedback from the organization and frequent meetings were continuous. Now that a trusted and sustaining partnership has been established, new discussions around potential solutions for meeting the needs of dual-language learners and systematic pathways to bridge general and special education instruction are the focus of future collaborative work. In all cases, the emphasis on clear communication of our respective priorities and supporting the practice organization's goals has assisted in building trust.

For all our RPPs, we cultivated these relationships using the following steps. First, we decided to schedule frequent meetings (usually monthly) with our partners to support progress, make decisions, and solve problems. Second, we aimed to create an open and safe space for all team members (e.g., knowledge brokers, organizational leadership, practitioners, researchers, and research staff) to share their opinions and perspectives, to cultivate respect, and to recognize the value of varied expertise—researchers know science and practitioners know practice. Third, it was important for all team members to understand each other's work demands and to set realistic goals. This last condition is particularly important during unexpected circumstances that may affect the progression of a partnership.

One example of unexpected circumstances is the COVID-19 pandemic that forced most schools to shut down and pivot to virtual or hybrid learning and paused many in-person research activities. The pandemic has changed the educational and research landscapes and overwhelmed many school districts. However, amid so much uncertainty, one thing remained constant: It was imperative to continue efforts in improving general and special education practices to support all students. Understanding the demands of our partners led to our decision to pivot to online kindergarten screening to identify DLD and dyslexia risk. Adjusting our routines, process, and research activities as needed was imperative for continued success in our partnerships. These endeavors would not have been possible without trust and continuous understanding of each other's needs and challenges.

In summary, we learned through our three RPPs that every practice organization will have a different level of interest and capacity for engaging in partnership work, as well as varying practice priorities that will impact the initiating and building of trusting relationships. Our experiences also suggest that it is important for research partners to understand that, for some practice organizations, their needs might necessitate immediate focus on the organization's practice goals and/or engagement in research. While for other practice organizations, extensive meetings and discussions surrounding needs, barriers, and facilitators to practice may be necessary before launching research projects or producing knowledge to inform practice broadly. Yet, for some practice organizations, engaging in partnership work may not be a current priority despite researchers having funding for research or support and knowledge to give in the organization's practice goals. Our RPPs have taught us that the key ingredients to building trust and cultivating relationships include (a) efforts to identify and initiate contact with a knowledge broker who can facilitate trust-building with organizational leaders; (b) engaging in consistent and open communication via meetings and soliciting feedback; (c) honoring each partner's knowledge and needs, demonstrating a commitment to working together to meet both research and practice goals; and (d) responsive and agile solutions to challenges or changes in priorities.

2. Conducting Rigorous Research to Inform Action

Effective RPPs include a research focus that balances rigor with feasibility in the practice organization. Finding the right balance between scientific rigor and feasibility is a necessary component to maintaining a mutually beneficial partnership. Without it, we cannot expect that schools will successfully implement and sustain practices that benefit students with learning disabilities.

For our partnerships, the question of balancing rigor and feasibility became especially relevant during the implementation of whole-classroom screeners to identify kindergarten students who may be at risk for DLD and dyslexia for one of our federally funded grants. While we aimed for rigor in our methods by standardizing our administration protocols, we also needed to ensure that screening was feasible in all classrooms. The schools in our practice organizations varied greatly across and within the districts in terms of their characteristics and capacity to support universal screening practices. Whole-classroom screening can be a quick way to screen all students at once; however, contextual factors that are not reflected in administration protocols may hinder successful implementation. For example, many kindergarten classrooms had larger-than-usual enrollments that required additional staff and support to facilitate implementation of the screening. Furthermore, teachers had to introduce additional elements during administration to support students who needed breaks or were inattentive, such as interrupting administration or using additional prompts. These shifts in the research protocol illustrate the importance of adaption of clinical practices for adoption in real-world settings and how to balance scientific rigor and fidelity with adaption necessary for high levels of implementation.

One meaningful way for achieving implementation outcomes such as acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility is to seek input from practitioners who are more knowledgeable than researchers about the environments they work in and populations they serve. For example, we solicited input from teachers to determine facilitators and barriers to the implementation of our screeners during COVID-related remote learning (Komesidou et al., 2022). Teachers reported that the screeners were quick, easy to use, and readily accessible. In addition, they appreciated that students could complete them independently and that parents could experience this process. Teachers, however, raised concerns about the screening timing, preparation required, specific technical features, and appropriateness for certain populations (e.g., bilingual students). Overall, these findings demonstrate the need to collect feedback from teachers and use it to tailor screening practices to unique settings. In doing that, we can achieve a balance between rigor and feasibility and guarantee the uptake of universal screening in schools.

In summary, we learned through our three RPPs that researchers must align scientific rigor with practice realities to increase the likelihood of feasibility and generate useable results. Our experiences also suggest that it is important to solicit perspectives of school staff around practice implementation in the planning, piloting, and execution phases of research to better understand their routine practice and specify strategies for adaptation. This intentional act has the potential to improve implementation outcomes in our field to close the research-to-practice gap. Our RPPs have taught us that the key ingredients to conducting rigorous clinical practice research includes (a) efforts to identify partners with shared clinical practice research interests and mutually beneficial goals, (b) commitment to balancing adaption and feasibility with rigorous research and implementation fidelity, and (c) solicitation of feedback from practitioners to learn about the barriers and facilitators to implementation.

3. Supporting the Partner Practice Organization in Achieving Its Goals

RPPs provide research and evidence to support improvements by identifying strategies and informing implementation of strategy deployment. During partnership meetings, the goals of both the researchers and the partner practice organization need to be discussed to ensure that efforts are mutually beneficial. Practitioners will be more willing to engage in RPPs if they know that researchers are willing to support them in achieving their goals and not just research agendas. For example, recent state legislation in the states where our partners resided have required schools to screen all kindergarten children for dyslexia. However, our partner practice organizations requested more guidance on identifying evidence-based screening tools for the age range and disorder and on the subsequent implementation of a universal screening process. State mandates gave very little guidance for schools on how to select and administer appropriate screening tools. We surveyed empirical literature and advised our partner practice organizations on currently available screening tools for dyslexia along with their pros and cons. Additionally, we proposed to use our researcher-developed screening instrument, which showed promising results for identifying children at risk for DLD and dyslexia in kindergarten. Ultimately, our partner practice organizations decided to administer our screening tool in their kindergarten classrooms which ensured they would meet the new legal requirements for screening while simultaneously assisting us in validating it.

Another example in our pursuit to support the goals of our partners was through the creation and provision of professional development to help staff expand their knowledge and use of the Science of Reading (Defining Movement, 2021). All three practice organizations were interested and helped facilitate professional development seminars for their teachers, SLPs, special education service providers, instructional aides, and administrators. Additionally, these seminars provided an opportunity to engage with practitioners to determine the social validity (i.e., acceptability) of our screening instrument in the practice partner organizations. Although feasibility is an important marker for potential uptake of an evidence-based practice, social validity of the practice is necessary for successful and sustainable implementation (Miramontes et al., 2011; Strain et al., 2012). Comparatively, social validity relates to the professional goals and ideologies of practitioners. Professional development seminars assisted us in gauging their beliefs, values, and goals within the context they practice. Using this information, we adapted our measure as needed to reach the highest possible implementation fidelity. This, in turn, assisted the practice organizations in meeting their practice goals of abiding by the state requirements to screen children in kindergarten for dyslexia using psychometrically sound measures.

In summary, we learned through our three RPPs that supporting our partner practice organization is an ongoing process and one that relies on careful planning, implementation, and evaluation of proposed activities. Our experience also suggests that it is possible to support the practice goals of the practice organization in mutually beneficial ways, such as our screening tool validation efforts that also met the legal requirements for universal screening. Additionally, providing professional development events can help practice organizations meet their practice goals while also providing opportunities for researchers to seek out important practitioner perspectives. Our RPPs have taught us that key ingredients to supporting the partner practice organization in achieving their goals include (a) engaging in strategic brainstorm meetings to identify clinical practice goals that can be supported by researchers and (b) soliciting ongoing input from the practice organization to edit and refine goals and actions.

4. Producing Knowledge to Inform Educational Improvement Efforts Broadly

Dissemination plans are integral to RPPs and should be developed together to ensure dissemination to the broader research community and to support scaleup of the rigorous research at the partner practice organization and similar targeted settings. In all our RPPs, not only are the researchers committed to publishing and disseminating their research findings in traditional peer-reviewed forums—deemed important in the university and grant-funding worlds—but the researchers also worked with partner practice organizations to disseminate in contexts considered important in their worlds. These efforts included, but were not limited to, presenting the partnership results to relevant stakeholder groups and organizations that directly affect policy and curriculum for the schools and districts within their state and regions. With these partnerships, we are in a unique position to advance work on real-world implementation and reduce the research-to-practice gap.

In one RPP, the findings of the large multisite randomized control trial supported the creation of a free classroom-based (tier 1) language comprehension curriculum to improve reading outcomes (Language and Reading Research Consortium, n.d.) available for easy download from the Internet by any practitioner. Additionally, it resulted in scientifically published research on the language basis of reading highlighting the dissemination of our project findings in both practitioner and research contexts. Subsequent projects utilized this curriculum to study its effectiveness as a small group (tier 2) and intensive (tier 3) intervention, further informing clinical practice. Most recently, this has led to the dissemination of our methods through a paper under review (Curran et al., 2021) discussing the use of the Minimal Intervention Needed for Change approach (Glasgow et al., 2014) to design studies or adapt interventions to real-world clinical settings.

In relation to our large NIH multisite grant work across all three practice organizations, we have found that we have sufficient knowledge about the benefits of universal screening, but we do not have enough evidence on how to implement and sustain screening practices in a diverse range of schools. As part of our efforts to promote scaleup, we have also created professional development sessions to train practitioners in our partner organizations to implement screening practices. Additionally, thanks to our recent efforts, we are now starting to gain insight into barriers and facilitators for sustainable screening practices (Komesidou et al., 2022). To our knowledge, ours is the first study to discuss specific factors that can hinder or facilitate implementation of DLD and dyslexia screening.

These past few years have reiterated that the translation of research findings into routine practice is a complex task requiring systematic methods of inquiry aimed at improving the fit of a program within the local context. This includes personalized dissemination attempts such as community-based presentations and professional development events. In these localized contexts, we can incorporate knowledge gleaned from the partnership showcasing the utility and feasibility of our screening and intervention practices for adoption and potential scaleup. Additionally, the knowledge produced from these partnerships has resulted in conducting two large-scale federally funded research grants focused on understanding the mechanisms related to language and literacy development, screening, and intervention for literacy disabilities; one small business–funded intervention study; and commitment to extend the work by partnering on a newly funded federal grant to study small-group language intervention.

In summary, through our three RPPs, we learned a lot about how to produce and disseminate knowledge that can lead to educational improvement efforts. In fact, this clinical focus article serves one of our goals to disseminate this knowledge to assist others who wish to engage in similar work and influence much needed change in research, practice, and policy. Our RPPs have taught us that the key ingredients to producing knowledge to inform educational improvement efforts broadly require thoughtful dissemination plans that include (a) consideration of contextual factors that may accelerate or impede implementation of clinical practices, (b) cultivating relationships with our practitioners with an emphasis on amplifying their voices, (c) understanding of elements of effective professional development, and (d) targeting both scientific and practice outlets at both scale and local venues.

5. Capacity Building of Participating Stakeholders to Engage in Partnership Work

Successful and sustainable RPPs reflect a partnership culture in which there is a shared commitment to both research and practice success across all stakeholders: researchers, practitioners, practice organizations, and research organizations. Practitioners and practice organizations need to see the benefit of engaging in rigorous research and translating that research to improve practice and outcomes for their patients or students. Researchers need to see the value in understanding the perspectives and contexts of the practitioners and the organizations they practice in so that practices can be made accessible, feasible, and maintain adequate fidelity.

In all three of our RPPs, our practice partners were engaged in and provided support for scheduling, space, and coordination of research, and felt ownership in the successful implementation and results of the researcher-driven clinical initiatives. Similarly, the researchers were committed to building the capacity of the partner practice organizations through ongoing and open discussions and more formally through the creation and deployment of professional development series, which met some of the practice goals of the practice organizations. These extensive researcher-developed continuing education opportunities resulted in helping the partner practice organizations and practitioners to better understand the science of reading and how to administer language and literacy screening, assessment, and interventions accordingly.

As for the researchers, we developed useful skills in managing partnerships, communicating with stakeholders, and mitigating conflicts. These partnerships also provided opportunities for undergraduate and graduate communication sciences and disorders students, as well as doctoral and postdoctoral research fellows, to engage in and lead various research and practice activities while learning about the unique ecosystems of schools in the United States and gaining an appreciation of the intricacies of implementation in real-world practice settings. Finally, this work has solidified the urgency of preventive frameworks for the timely identification and support of students with language and literacy disabilities and long overdue changes in traditional research methods for both the researchers and practitioners involved.

In summary, over the last 9 years and three RPPs, we learned that building the capacity of both research and practice partners to engage in partnership work is an ongoing and dynamic process. Our experience also suggests that, when both partners feel that the partnership is mutually beneficial, they are more likely to sustain and expand the partnership long term. Our RPPs have taught us that the key ingredients to building capacity for and engaging in partnership work include (a) authentic and frank conversations about stakeholder priorities and bandwidth, (b) frequent check-ins with all stakeholders to revisit goals and their mutuality, and (c) efforts to disseminate the outcomes of the partnership work to highlight the mutual benefits of this type of work and encourage continuation.

Discussion

Overall, these three partnerships have resulted in (a) the finalization of a free and effective language comprehension whole-classroom curriculum for prekindergarten through third grade (https://larrc.ehe.osu.edu/curriculum/), (b) efforts to early identify children at risk for language and literacy difficulties by piloting a researcher-developed screening tool (Hogan et al., 2021), (c) new initiatives to bring implementation science into schools, (d) increased knowledge among practitioners about the science and practice of reading, and (e) a newly funded federal grant using a randomized control trial to establish the efficacy of a small-group (tier 2) intervention for first and second grade students at risk for language and literacy difficulties (NIH R01 DC018823). In our work, it is important to maintain some flexibility in our planning to meet our research goals and our partners' practice goals. Flexibility balances rigor with adaptability and ensures that RPPs are indeed mutually beneficial. Using this approach, we have sustained our RPPs through the strain of COVID-19 pandemic school closures. Most notably, the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the importance of the commitment of research partners to support practice partner organizations in achieving their goals. The ever-changing experiences and challenges faced by schools during the pandemic were, at best, overwhelming and, at worst, a crisis to education and learning. Certainly, the changes to instruction impacted research agendas. By pivoting to support our practice organization partners in their needs to meet legislation requirements despite being virtual or hybrid, however, we were able to also advance our research by trialing new digital methods that could improve reach and feasibility overall.

Our RPPs showcase three distinct partnerships that exemplify long-term and sustainable research–practice collaborations and the potential ripple effects in the community, based on professional development, clinical training, and dissemination of knowledge to improve clinical practice. Thus far, these organizational level RPPs have spanned three distinct projects across multiple tiers of instruction and modalities. They have created opportunities for graduate students in our research and clinical training programs to receive practical experiences in assessment, intervention, and interprofessional collaboration. They also informed similar projects in other school districts to address the needs of students with language and literacy difficulties. Most importantly, these RPPs demonstrate the need for consistent and honest interactions with school administrators and relevant stakeholders, in times of funding and no funding, to create system-level changes and achieve mutual goals.

Researchers and practitioners interested in building partnerships in service of improving implementation of clinical practice processes can use Henrick's five dimensions of RPPs as a guidepost for initiating and sustaining such partnerships. Starting with the first dimension of building trust by having open and frequent conversations, managing both partners' expectations, striving for aligned goals and mutual benefits and keeping the relationship health as central to the partnership are foundational to successful collaborations.

Conclusions

In this clinical focus article, we discussed our continuous efforts to build and sustain RPPs with schools across the United States. These RPPs have resulted in improved practices for researchers and practitioners and have yielded usable knowledge to inform others who may be interested in conducting similar work. We detailed three unique examples of RPPs and their partnership activities, and we showcased specific examples using the five dimensions of RPPs to illustrate the effectiveness of these partnerships. In addition, we discussed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our work and how we continued meeting our research priorities while supporting our partner organizations' goals. Overall, our collective efforts have yielded improved early school-age language and literacy screening procedures, as well as classroom and small group language interventions with potential for not only implementation but also sustainable adoption by our partner practice organizations and beyond. The benefits of these RPPs extend beyond the immediate impact on the research and practice partners. By engaging in these partnerships, several insights have been gleaned that we believe can be generalized to other contexts. Practitioners and researchers working in settings different than educational systems can apply the five RPP dimensions when assessing their partnerships and may find collaboration principles and examples discussed relevant and useful in their work to close the research-to-practice gap.

Acknowledgments

Funding for some of the research projects described in this clinical focus article include Institute of Education Sciences Reading for Understanding Research Initiative (R305F100002; PIs: Justice, Gray, Catts, & Hogan), National Institutes of Health R01 grant mechanism (R01 DC016895; PIs: Hogan & Wolter), and an RSM Foundation Grant (PIs: Hogan & Komesidou). The authors also wish to thank their partner practice organizations (school districts and elementary schools) and the teachers, staff, students, and caregivers that supported our research efforts and built meaningful relationships with them.

Funding Statement

Funding for some of the research projects described in this clinical focus article include Institute of Education Sciences Reading for Understanding Research Initiative (R305F100002; PIs: Justice, Gray, Catts, & Hogan), National Institutes of Health R01 grant mechanism (R01 DC016895; PIs: Hogan & Wolter), and an RSM Foundation Grant (PIs: Hogan & Komesidou).

References

- Bauer, M. S. , & Kirchner, J. (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Research, 283, 112376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager, C. , Caringi, J. C. , van den Pol, R. , Crosby, L. , O'Connell, K. , Trautman, A. , & McDonald, M. (2012). Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2012.664862 [Google Scholar]

- Caringi, J. C. , Stanick, C. , Trautman, A. , Crosby, L. , Devlin, M. , & Adams, S. (2015). Secondary traumatic stress in public school teachers: Contributing and mitigating factors. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(4), 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2015.1080123 [Google Scholar]

- Christian-Brandt, A. S. , Santacrose, D. E. , & Barnett, M. L. (2020). In the trauma-informed care trenches: Teacher compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and intent to leave education within underserved elementary schools. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C. E. , & Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16631750 [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C. E. , Penuel, W. R. , & Geil, K. E. (2013). Research-practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in school districts. William T. Grant Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED568396.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Curran, M. , Komesidou, R. , & Hogan, T. P. (2021). Less is more: Implementing the ‘Minimal Intervention Needed for Change (MINC)' approach to increase contextual fit of speech-language interventions. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/pu6sa [DOI] [PubMed]

- Defining Movement. (2021). The science of reading: A defining guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

- Dobbins, M. , Greco, L. , Yost, J. , Traynor, R. , Decorby-Watson, K. , & Yousefi-Nooraie, R. (2019). A description of a tailored knowledge translation intervention delivered by knowledge brokers within public health departments in Canada. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0460-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, N. F. , & Burshnic, V. L. (2019). Implementation science: Tackling the research to practice gap in communication sciences and disorders. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_PERS-ST-2018-0000 [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, N. F. , Campbell, W. N. , & Hinckley, J. J. (2015). Implementation science: Buzzword or game changer. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), S1827–S1836. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-15-0302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, C. C. , Davidson, K. L. , Repko-Erwin, M. , Penuel, W. R. , Quantz, M. , Wong, H. , Riedy, R. , & Brink, Z. (2018). A descriptive study of the IES Researcher–Practitioner Partnerships in Education Research Program: Final report (Technical report no. 3) (p. 111). National Center for Research in Policy and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. E. , Fisher, L. , Strycker, L. A. , Hessler, D. , Toobert, D. J. , King, D. K. , & Jacobs, T. (2014). Minimal intervention needed for change: Definition, use, and value for improving health and health research. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-013-0232-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H. , McKenna, M. , Barker, R. M. , & Brown, T. H. (2019). Research–practice partnership: Application to implementation of multitiered system of supports in early childhood education. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_PERS-ST-2018-0005 [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H. , & Olswang, L. (2017). Is there a science to facilitate implementation of evidence-based practices and programs? Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 11(3–4), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17489539.2017.1416768 [Google Scholar]

- Gul, R. B. , & Ali, P. A. (2010). Clinical trials: The challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(1–2), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock, R. G. (1973). The change agent's guide to innovation in education. Educational Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Henrick, E. C. , Cobb, P. , Penuel, W. R. , Jackson, K. , & Clark, T. (2017). Assessing research-practice partnerships: Five Dimensions of effectiveness. William T. Grant Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, T. P. , Komesidou, R. , Wolter, J. A. , Ricketts, J. , & Alonzo, C. N. (2021). Using the simple view of reading to identify risk for developmental language disorder and dyslexia [Manuscript in preparation] .

- Huang, K.-Y. , Kwon, S. C. , Cheng, S. , Kamboukos, D. , Shelley, D. , Brotman, L. M. , Kaplan, S. A. , Olugbenga, O. , & Hoagwood, K. (2018). Unpacking partnership, engagement, and collaboration research to inform implementation strategies development: Theoretical frameworks and emerging methodologies. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydon, S. , Wong, M. , Langley, A. K. , Stein, B. D. , & Kataoka, S. H. (2015). Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(2), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert, L. (2006). Academic-practice partnerships in practice research: A cultural shift for health social workers. Social Work in Health Care, 43(2–3), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v43n02_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komesidou, R. , Feller, M. , Wolter, J. A. , Ricketts, J. , Rasner, M. , Putman, C. , & Hogan, T. P. (2022). Educators' perceptions of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of screeners for developmental language disorder and dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Language and Reading Research Consortium. (n.d.). Let's Know! Curriculum. Retrieved May 26, 2021, from https://larrc.ehe.osu.edu/curriculum/

- Miramontes, N. Y. , Marchant, M. , Heath, M. A. , & Fischer, L. (2011). Social validity of a positive behavior interventions and support model. Education and Treatment of Children, 34(4), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2011.0032 [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olswang, L. B. , & Goldstein, H. (2017). Collaborating on the development and implementation of evidence-based practices: Advancing science and practice. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 11(3–4), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17489539.2017.1386404 [Google Scholar]

- Olswang, L. B. , & Prelock, P. A. (2015). Bridging the gap between research and practice: Implementation science. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), S1818–S1826. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-14-0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E. K. , Landsverk, J. , Aarons, G. , Chambers, D. , Glisson, C. , & Mittman, B. (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E. K., Silmere, H. , Raghavan, R. , Hovmand, P. , Aarons, G. , Bunger, A. , Griffey, R. , & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain, P. S. , Barton, E. E. , & Dunlap, G. (2012). Lessons learned about the utility of social validity. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2012.0007 [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, V. , Easton, J. Q. , & Supplee, L. H. (2017). Research-practice partnerships: Building two-way streets of engagement. Social Policy Report, 30(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2017.tb00089.x [Google Scholar]