Abstract

Background and Aims

Radiofrequency ablation is a commonly used treatment for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), but postoperative rehabilitation exercises are needed to reverse left ventricular structural and functional abnormalities. This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the intervention effect of exercise training in patients with AF after radiofrequency ablation.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify articles in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from January 1, 2010 to December 1, 2021. The mean difference with 95% CI was pooled for continuous variables. We used Review Manager 5.3 for the standard meta-analysis. This study followed the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Results

Ten randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included, with a total of 892 patients with AF. The quality of one study was grade A, and the rest were grade B. The results of the meta-analysis showed that the improvement of 6 min walking distance (MD = 34.42, 95% CI: 3.20 to 65.63, P=0.03), peak oxygen uptake (MD = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.14 to 2.78, P < 0.001), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (MD = 0.09, 95% CI:0.01–0.17, P=0.02), resting heart rate (MD = −4.50, 95% CI: −8.85 to −0.14, P=0.04), and physical component summary (PCS) (MD = 3.00, 95% CI: 0.46 to 5.54, P=0.02) in the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion

Exercise training can improve the level of exercise endurance and cardiac function in patients. However, the results were limited by the quantity and quality of the studies. Large samples and high-quality studies are still needed to verify its long-term efficacy.

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, and its morbidity and mortality show an increased tendency with age [1, 2]. It can cause heart failure, stroke, thromboembolism, and other serious life-threatening events [3]. According to a survey [4], there are about 8 million cases of AF in China, accounting for about 0.77%. AF has become an important health problem that affects global health and hinders social and economic development. The current treatments for AF include drug therapy and surgical treatment (radiofrequency ablation (RFA)). Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) RFA has become the first choice for treating AF due to its minor trauma and fast postoperative recovery [5]. However, there is a recurrence rate of about 30% after catheter ablation [6]. Even after secondary ablation, the recurrence rate is as high as 7% to 24% [4], and postoperative intervention is still required to improve the structure and function of the heart.

Postoperative patient management focuses on controlling heart rate and rhythm, reducing the risk of stroke and related adverse cardiovascular events, and improving lifestyle. However, there is a lack of emphasis on routine exercise therapy after AF. Exercise rehabilitation is a comprehensive assessment of individual health, physical strength, cardiovascular function, exercise tests, and risk stratification. Doctors prescribe the corresponding exercise prescriptions to help patients recover physically and mentally. Several studies [7, 8] have confirmed that exercise rehabilitation plays a vital role in improving coronary heart disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and other cardiovascular diseases, but few studies report exercise rehabilitation used in AF patients after RFA. There are no systematic studies to clarify its role in the management of AF, and no guidelines or consensus have been formed. Previous studies on the impact of exercise rehabilitation on AF focused on the whole population of AF, and there was no meta-analysis after AF ablation. This study aimed to explore the improvement effect of exercise on patients with AF after RFA and to provide evidence for the formulation of postoperative rehabilitation training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A literature review was conducted in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Library Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, Web of Science, CINAHL EBSCO, PubMed, Scopus, CBM, China Knowledge Network, WanFang, and VIP databases to identify eligible publications in Chinese and English. The search period was from January 2010 to July 2021. The Chinese search keywords were “atrial fibrillation,” “exercise,” “aerobic exercise,” “resistance training,” “exercise training,” “exercise rehabilitation,” and “activity.” The English search keywords were “atrial fibrillation,” “aerobic exercise,” “exercise rehabilitation,” “training/exercise” and “randomized controlled trial.” We also manually searched the references of relevant reviews, systematic reviews, and included studies to identify other potentially eligible studies.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) Study type: randomized controlled trials (RCTs). (2) Patients: adult patients 18 years of age or older who suffered from AF and received RFA, with informed consent obtained. (3) Interventions: the control group received routine care, including drugs, RFA, psychological counseling, health education, and discharge guidance; the experimental group implemented a structured exercise program on the basis of the corresponding control group, including aerobic, resistance exercise training, joint training (aerobic and resistance), functional electrical stimulation, and physical therapy of inspiratory muscle training. (4) Outcomes: 6-minute walking distance (6MWD), peak oxygen uptake (peak VO2), resting heart rate, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and quality of life.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) The full text was not available; (2) relevant outcome indicators were not mentioned or unclearly expressed; (3) duplicate publications; and (4) animal studies, case reports, comments, abstracts, meeting minutes, and editorials.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers conducted the articles' screening processes and extracted the required information. If there were any disagreements, a third reviewer was consulted to make a final decision. The content of the information included: (1) authors and their country, publication year; (2) number of study participants, grouping; (3) intervention measures: intervention content, intervention frequency/period of each group; and (4) outcome indicators. The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used to evaluate the quality of RCTs, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selectivity reporting, and other sources of bias [9]. If the included literature ultimately met the above items with low bias, its quality grade was A; if it partially conformed to these items with moderate bias, its quality grade was B; and if it was utterly noncompliant, its quality grade was C, and such a study should be excluded.

2.4. Data Analysis

The Review Manager (RevMan 5.3) software was used for the meta-analysis. The mean difference (MD) with 95% CI was pooled for continuous variables. The significance level was set at 0.05, with a 2-tailed test used. The I2 statistic was used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies, and a value of >50 indicated significant heterogeneity. Because of the small number of studies, we did not test publication bias because any test would have had low power to distinguish between chance and real asymmetry. We assessed the risk of bias in individual studies using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. The quality and consistency of the results were assessed by calculating the combined effects after excluding each selected study. We performed this meta-analysis in compliance with the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

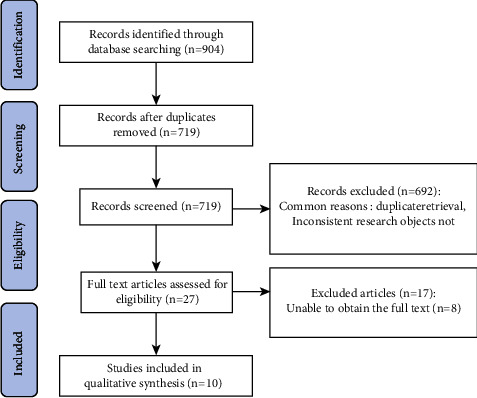

A total of 904 articles were retrieved. After removing 185 duplicate articles by NoteExpress software, ten RCTs were finally included [10–19], including eight in English [10–12, 15–19] and two in Chinese [13, 14]. The flow chart of literature screening is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature screening.

3.2. Basic Characteristics of the Included Studies

A total of 892 patients were included in this study, including 445 patients in the experimental group and 447 patients in the control group. The basic characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Included studies | Country | Age | Sample size | Intervention measures | Intervention frequency | Intervention period | Outcome indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | Control group | Experimental group | Control group | Experimental group | Control group | |||||

| Osbak et al. [10] | Denmark | 69.5 ± 7.3 | 70.9 ± 8.3 | 24 | 23 | Cycling, walking on stairs, running, balling, and interval training | Habitual physical activity | 3 times/w, 30 min/each time | 12 w | ①④ |

| Lakkireddy et al. [11] | USA | 60.6 ± 11.5 | 63.9 ± 7.6 | 49 | 53 | Yoga training combined with medication | Routine care measures | 2 times/w; 60 min/times | 12 w | ④ |

| Wahlstrom et al. [12] | Sweden | 64 ± 7 | 63 ± 8 | 33 | 36 | Yoga training combined with medication | Routine drug treatment | 1 time/w; 60 min/times | 12 w | ④⑤ |

| Cao et al. [13] | China | 50.9 ± 6.23 | 51.08 ± 5.81 | 55 | 55 | Aerobic exercise, mainly walking | Routine interventions | 3 times/w | 1 y | ①③ |

| Chen et al. [14] 2019 | China | 51.2 ± 7.4 | 50.6 ± 7.6 | 60 | 62 | Aerobic exercise, mainly walking | Routine medication and health education | 3-4 times/w, performed every other day | 1 y | ①③ |

| Malmo et al. [15] | Norway | 56 ± 8 | 62 ± 9 | 26 | 25 | Aerobic exercise, mainly walking/running | Routine habitual exercise | 3 times/w; 45 min/ | 12 w | ②③④⑤ |

| Risom et al. [16] | Denmark | 60 ± 9 | 59 ± 12.25 | 105 | 105 | Sports training and psychological education and consultation | Routine care measures | 3 times/w | 12 w | 1 |

| Kato et al. [17] | Japan | 67 ± 10 | 65 ± 8 | 28 | 31 | Moderate-intensity endurance and resistance training | Routine care measures | 3 times/w; 30 min/times | 6 m | ①②③④ |

| Joensen et al. [18] | Denmark | 62.2 ± 10 | 60.2 ± 8.9 | 28 | 24 | Interval training combined with rehabilitation education | Routine treatment | 2 times/w; 1 h/time | 12 w | ①② |

| Skielboe et al. [19] | Denmark | 61.4 ± 3 | 63.8 ± 3.3 | 37 | 33 | High-intensity exercise | Traditional low-intensity exercise | 2 times/w; 60 min/time | 12 w | 1 |

Note: 6MWD: 6-minute walking distance; peak VO2: peak oxygen uptake; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; quality of life: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS).

3.3. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

Among the collected literature, one study [12] was grade A, and the rest were grade B, with moderate overall quality. Eight studies [11–13, 15–19]described randomization methods; four studies [11, 12, 16, 17] described random allocation concealment; three studies [10, 12, 16] mentioned blinding methods, but only one [12] involved blinding of participants, personnel, and assessment; one study [16] had data loss. During the follow-up period, twenty-six patients in the experimental group and twenty-seven in the control group withdrew from the study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

| Included studies | Randomization methods | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Completeness of outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants and personnel | Assessment | ||||||

| Osbak et al. [10] | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Lakkireddy et al. [11] | Dice rolling | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Wahlstrom et al. [12] | Dice rolling | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Cao et al. [13] | Number method | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Chen et al. [14] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Malmo et al. [15] | Computer | Unclear | No | Yes | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Risom et al. [16] | Computer | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Incomplete | No | Unclear |

| Kato et al. [17] | Computer | Yes | No | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Joensen et al. [18] | Number method | No | No | Yes | Complete | No | Unclear |

| Skielboe et al. [19] | Computer | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Complete | No | Unclear |

3.4. Meta-Analysis Results

3.4.1. 6-Minute Walking Distance (6MWD)

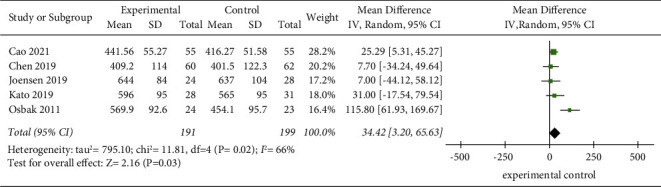

Five studies [10, 13, 14, 17, 18] evaluated the effect of exercise on the 6MWD of AF patients. Given that the trials pooled together are not drawn from the same population and also given the considerable clinical heterogeneity between the studies, only random-effects model should be used throughout the whole study and for all the analysis (I2 = 66%, P=0.02). The results showed that the 6MWD of the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group (MD = 34.42, 95% CI: 3.20 to 65.63, Z = 2.16, P=0.03) (Figure 2). The sensitivity analysis showed that the study by Osbak et al. [10] was the cause of the heterogeneity of the results, but the analysis results did not change, indicating that the results were stable, as shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of the 6MWD between the two groups.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of exercise on the 6MWD of AF patients.

| Included studies | Heterogeneity test | Overall effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P | MD (95% CI) | |

| Original meta-analysis | 66 | 0.02 | 34.42 [3.20 to 65.63] |

| (Deleted) Joensen et al. [18] | 73 | 0.01 | 40.81 [3.40 to 78.23] |

| (Deleted) Kato et al. [17] | 75 | 0.008 | 35.96 [−3.31 to 75.22] |

| (Deleted) Osbak et al. [10] | 0 | 0.80 | 21.53 [5.48 to 37.59] |

| (Deleted) Cao et al. [13] | 74 | 0.01 | 38.94 [−8.55 to 86.43] |

| (Deleted) Chen et al. [14] | 72 | 0.01 | 41.92 [2.91 to 80.92] |

3.4.2. Peak Oxygen Uptake (Peak VO2)

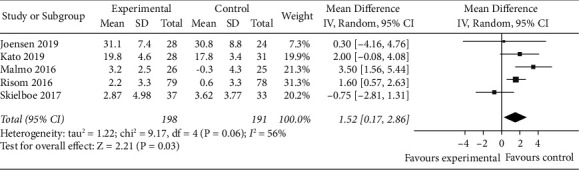

A total of five studies [15–19] reported the effect of exercise on peak VO2 of AF patients. The random-effects model was selected for meta-analysis (P=0.06, I2 = 56%). The results showed that the peak VO2 of the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (MD = 1.52, 95% CI: 0.17 to 2.86, Z = 2.21, P < 0.05) (Figure 3). The sensitivity analysis showed that the study by Skielboe et al. [19] was responsible for the heterogeneity of the results, but there was no change in the analysis, indicating that the results were stable, as shown in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of peak VO2 between the two groups.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of exercise on the peak VO2 of AF patients.

| Included studies | Heterogeneity test | Overall effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P | MD (95% CI) | |

| Original meta-analysis | 56 | 0.06 | 1.52 [0.17 to 2.86] |

| (Deleted) Joensen et al. [18] | 66 | 0.03 | 1.61 [0.13 to 3.09] |

| (Deleted) Kato et al. [17] | 63 | 0.07 | 1.36 [−0.38 to 3.10] |

| (Deleted) Malmo et al. [15] | 37 | 0.19 | 1.05 [−0.19 to 2.29] |

| (Deleted) Risom et al. [16] | 67 | 0.03 | 1.42 [−0.68 to 3.51] |

| (Deleted) Skielboe et al. [19] | 12 | 0.33 | 2.01 [1.07 to 2.96] |

3.4.3. Resting Heart Rate

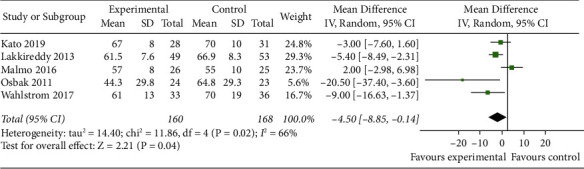

Five studies [10–12, 15, 17] evaluated the effect of exercise on the resting heart rate of AF patients. The heterogeneity between these studies was considerable (I2 = 66%, P=0.02). The meta-analysis using the random-effects model showed that the resting heart rate of the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group (MD = −4.50, 95% CI: −8.85 to −0.14, Z = 2.02, P=0.04) (Figure 4). The sensitivity analysis showed that the study by Malmo et al. [15] was the cause of the heterogeneity of the results, but the analysis results did not change, indicating that the results were stable, as shown in Table 5.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of resting heart rate between the two groups.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of exercise on resting heart rate of AF patients.

| Included studies | Heterogeneity test | Overall effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P | MD (95% CI) | |

| Original meta-analysis | 66 | 0.02 | −4.50 [−8.85 to −0.14] |

| (Deleted) Kato et al. [17] | 74 | 0.009 | −5.48 [−11.63 to 0.67] |

| (Deleted) Lakkireddy et al. [11] | 71 | 0.02 | −4.77 [−11.18 to 1.64] |

| (Deleted) Malmo et al. [15] | 40 | 0.17 | −5.92 [−9.63 to −2.21] |

| (Deleted) Osbak et al. [10] | 63 | 0.04 | −3.52 [−7.44 to 0.41] |

| (Deleted) Wahlstrom et al. [12] | 70 | 0.02 | −3.62 [−8.50 to 1.26] |

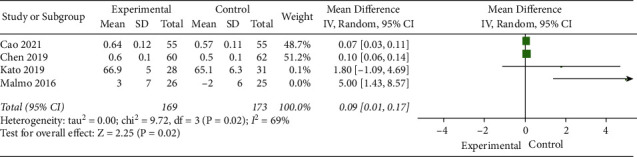

3.4.4. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF)

Four studies [13–15, 17] evaluated the effect of exercise on the LVEF of AF patients. The random-effects model was selected for meta-analysis (I2 = 69%, P=0.02). The results showed that LVEF in the experimental group was significantly better than that of the control group (MD = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.17, Z = 2.25, P=0.02) (Figure 5). The sensitivity analysis showed that the study by Malmo et al. [15] was the cause of the heterogeneity of the results, but the analysis results did not change, indicating that the results were stable, as shown in Table 6.

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of left ventricular ejection fraction between the two groups.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of exercise on the left ventricular ejection fraction of AF patients.

| Included studies | Heterogeneity test | Overall effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P | MD (95% CI) | |

| Original meta-analysis | 69 | 0.02 | 0.09 [0.01 to 0.17] |

| (Deleted) Kato et al. [17] | 76 | 0.02 | 0.09 [0.01 to 0.16] |

| (Deleted) Malmo et al. [15] | 19 | 0.29 | 0.09 [0.05 to 0.12] |

| (Deleted) Cao et al. [13] | 77 | 0.01 | 1.85 [−0.88 to 4.57] |

| (Deleted) Chen et al. [14] | 77 | 0.01 | 1.84 [−0.91 to 4.59] |

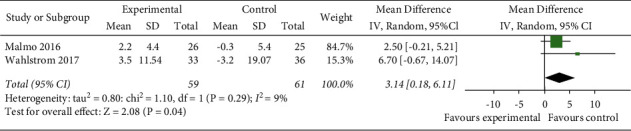

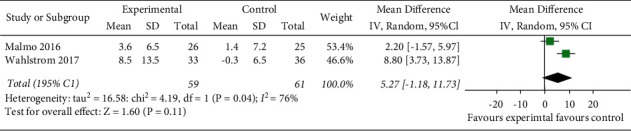

3.4.5. Changes in the Quality of Life

Two RCTs [12, 15] used SF-36 to evaluate the improvement in quality of life in AF patients with exercise. The random-effects model was selected for the meta-analysis. (I2 = 9%, P=0.29). The meta-analysis showed that the physical condition of the experimental group was better than that of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (MD = 3.14, 95% CI: 0.18 to 6.11, Z = 2.08, P=0.04) (Figure 6). The random-effects model was selected, and the improvement of MCS in the experimental group was lower than that of the control group. The difference was not statistically significant (MD = 5.27, 95% CI: −1.18 to 11.73, P=0.11) (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of physical component summary of the two groups.

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of the comparison of mental component summary of the two groups.

4. Discussion

RFA is an internationally recognized treatment method to prevent the onset of AF and can effectively maintain normal sinus rhythm for paroxysmal AF and persistent AF. Its primary benefit is to reduce the symptoms related to arrhythmia and improve the quality of life [20–22]. However, studies have found that several risk factors can affect the outcome of RFA, including the type of AF, duration, and complications (such as hypertension, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and sleep apnea syndrome). Currently, cardiac rehabilitation, which focuses on exercise rehabilitation, has been proven to play a positive role in controlling disease risk factors such as coronary heart disease, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction after PCI, and heart transplantation [23, 24]. However, few reports are available on patients receiving exercise rehabilitation after RFA, and the rehabilitation effect is still unknown.

This study explored the effect of exercise on patients with AF after RFA by meta-analysis. The results showed that compared with the control group, planned exercise rehabilitation could significantly improve the exercise tolerance, cardiac function, and physical condition of patients after RFA. The reason was that exercise rehabilitation could improve vascular endothelial function, be anti-inflammatory, reduce myocardial remodeling, and improve myocardial ischemia and antithrombotic effects, thereby effectively reducing the risk factors of AF [25].

Exercise intervention can significantly improve the exercise tolerance level of AF patients after RFA. This study carried out a quantitative analysis of 6MWD and peak VO2 indicators, which were the best indicators for evaluating exercise tolerance. The study results were consistent with Morseth et al. [26], who proposed that aerobic exercise could improve the exercise endurance of patients and the physical condition of patients with heart disease after surgery. The report of the postphysical condition is consistent with the conclusion. The reason might be related to the improvement of cardiac output, the increase of peripheral skeletal muscle oxygen utilization, and the correlation between 6MWD and oxygen uptake, thereby improving the exercise tolerance of patients after surgery.

Exercise can improve the heart function of AF patients after RFA. LVEF is one of the indicators reflecting the systolic function of the heart. Regular exercise can increase myocardial glucose uptake, promote the utilization of myocardial substrates, increase cardiac output, and improve left ventricular remodeling. This is especially important for AF patients, who can benefit from the improved systolic function. It is consistent with the effect of exercise intervention in the study by Yagishita et al. [27]. Resting heart rate is a relatively simple and direct indicator of understanding heart function. This study showed that AF patients receiving RFA had their resting heart rate decreased after exercise. The reason might be that exercise inhibited the vagus nerve of the heart activity and the sympathetic nerve activity was weakened [28], which improved the cardiac neuromodulation mechanism. Meanwhile, exercise caused adaptive changes in the structure of myocardial fibers, increased contractility, and strengthened blood supply, thereby reducing the burden on the heart.

Exercise can improve the physical condition of AF patients after RFA. In this study, PCS and MCS were used to reflect the quality of life of patients. After exercise, the physical condition of the patients improved, but their mental condition did not. Relevant studies have confirmed that exercise improves physical condition, but there are controversies about its role in mental health. Nourmohammadi et al. [29] reported that compared with the experimental group, the control group had higher mental health and euphoria levels, while Reed et al. [30] believed that after exercise rehabilitation, patients' mental health levels improved. The reason might be related to the severity of AF and the mode of exercise intervention, such as physical therapist-ledexercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (PT-X), prescription physical activity (PAP) [31], and whether the selection of exercise type was based on the patients' wishes. This indicates that in improving the quality of life of AF patients after RFA, medical staff should increase the initiative of patients, allow them to participate in the formulation of exercise programs, and pay attention to the subjective experience of patients during exercise to promote the mental and physical health of patients.

Due to individual differences among patients with AF, such as age restriction, gender difference, and multiple diseases, the selection of exercise patterns and exercise intensity for patients should be personalized. It is recommended to conduct an individualized pre-exercise evaluation before prescribing exercise to identify whether the patient has high-risk groups with an increased risk of exercise-related sudden death and other cardiovascular events. An RCT study showed that low-intensity and high-intensity exercise increased the exercise capacity of cardiovascular patients by 16% and 14%, respectively [19], thereby reducing the symptoms and burden of AF. Studies have confirmed that the comprehensive care of AF by the ABC pathway plays a potential role in reducing the risk of major adverse consequences [32]. Therefore, some researchers suggest that exercise rehabilitation and the ABC approach can be used together to highlight the advantages of each and maximize the benefits of postoperative prognosis and rehabilitation in patients with AF.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the inconsistency of various exercise schemes included in the study, we cannot further explore the impact of different motion characteristics on the results through subgroup analysis. Secondly, the heterogeneity of AF and the different severity of symptoms among different AF subtypes lead to large population differences and make it difficult to measure the burden of AF. Because the full text of the eight studies was not available, some important evidence may have been omitted. The included literature lacks sufficient evidence to determine the impact of exercise rehabilitation on the risk of postoperative death or hospitalization of AF. It is recommended to strengthen the research on postoperative complications of AF in the later stages. In the future, long-termfollow-ups will be conducted with standard exercise intervention programs, as well as conducting large-scale experimental studies on single and multiple exercise strategies to understand whether exercise intervention has a long-term impact on the indicators in this study and other important clinical results and to provide an effective clinical basis for the promotion of exercise intervention for AF patients after RFA.

To sum it up, the controversy on the role of exercise for AF patients after RFA mainly focuses on whether high-intensity exercise will lead to a poor prognosis, and the effects of mild- and medium-intensity exercise on prevention and treatment have been confirmed [33]; i.e., exercise intervention has positive significance for exercise tolerance, cardiac function, and physical condition of patients with AF. In the future, the formulation of exercise programs should be based on full evaluation, follow the principles of individualization and structuralization, and the decision should be made by both doctors and patients so that the form of exercise, exercise intensity, and frequency of exercise can meet the actual needs of patients, thereby improving patients' participation in sports, helping them maintain long-term exercise, and achieving the purpose of improving the prognosis of patients.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the Shanghai Putuo District Health Committee Research Project (No. 2021PTGL016) and the Shanghai Tongji Hospital National Natural Cultivation Project (No. GJPY2146).

Data Availability

All data are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lip G. Y. Heart rate variability in atrial fibrillation: the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. European Journal of Clinical Investigation . 2019;8(2):83–86. doi: 10.1111/eci.13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinese Association of Research Hospitals. The Chinese expert consensus statement on surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation 2020. Chinese Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery . 2021;37(3):129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinese Medical Association. Guideline for primary care of atrial fibrillation (2019) Chinese Journal of General Practitioners . 2020;19(6):465–473. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S. Comprehensive management of atrial fibrillation. Chinese Journal of Cardiology . 2019;47(8):593–594. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripathi B., Arora S., Kumar V., et al. Temporal trends of in-hospital complications associated with catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the United States: an update from Nationwide Inpatient Sample database (2011–2014) Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology . 2018;29(5):715–724. doi: 10.1111/jce.13471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun H., Zhou C. Research progress of risk prediction models recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. Practical Journal of Cardiac Cerebral Pneumal and Vascular Disease . 2021;29(7):136–140. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knuuti J., Wijns W., Saraste A., et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal . 2020;41(3):407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols S., McGregor G., Breckon J., Ingle L. Current Insights into exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic heart failure. International Journal of Sports Medicine . 2021;42(1):19–26. doi: 10.1055/a-1198-5573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gotzsche P. C., et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ . 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osbak P. S., Mourier M., Kjaer A., Henriksen J. H., Kofoed K. F., Jensen G. B. A randomized study of the effects of exercise training on patients with atrial fibrillation. American Heart Journal . 2011;162(6):1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakkireddy D., Atkins D., Pillarisetti J., et al. Effect of yoga on arrhythmia burden, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the YOGA My Heart Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2013;61(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahlstrom M., Rydell Karlsson M., Medin J., Frykman V. Effects of yoga in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation -a randomized controlled study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing . 2017;16(1):57–63. doi: 10.1177/1474515116637734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao P., Sun C., Ge W. Impacts of aerobic exercise on left ventricular structure, function, and exercise tolerance of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation. China Modern Doctor . 2021;59(7):10–12+16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X., Chen Y., Dong J. Effect of aerobic walking exercise after radiofrequency ablation on rehabilitation and life quality of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients. Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation . 2019;34(2):82–86. doi: 10.3870/zgkf.2019.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malmo V., Nes B. M., Amundsen B. H., et al. Aerobic interval training reduces the burden of atrial fibrillation in the short term: a randomized trial. Circulation . 2016;133(5):466–473. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Risom S. S., Zwisler A. D., Rasmussen T. B., et al. Cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care for patients treated with catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: results of the randomized CopenHeartRFA trial. American Heart Journal . 2016;181:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato M., Ogano M., Mori Y., et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for patients with catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled clinical trial. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology . 2019;26(18):1931–1940. doi: 10.1177/2047487319859974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joensen A. M., Dinesen P. T., Svendsen L. T., et al. Effect of patient education and physical training on quality of life and physical exercise capacity in patients with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation: a randomized study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine . 2019;51(6):442–450. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skielboe A. K., Bandholm T. Q., Hakmann S., Mourier M., Kallemose T., Dixen U. Cardiovascular exercise and burden of arrhythmia in patients with atrial fibrillation - a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One . 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170060.e0170060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pluymaekers N. A., Dudink E. A., Luermans J. G., et al. Early or delayed cardioversion in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine . 2019;380(16):1499–1508. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1900353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyong J., Amit G., Adler A. J., et al. Efficacy and safety of ablation for people with nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . 2016;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012088.pub2.CD012088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packer D. L., Mark D. B., Robb R. A., et al. Effect of catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2019;321(13):1261–1274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein E., Maisel S., Maysent K., Taub P. R. Cardiac rehabilitation for coronary artery disease: latest updates. Current Opinion in Cardiology . 2021;36:556–564. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyuno E., Iso Y., Tsujiuchi M., et al. Impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on the mid-term outcomes of patients after acute myocardial infarction treated with current acute-phase management and optimal medical therapy. Heart Lung & Circulation . 2021;30(9):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2021.03.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keteyian S. J., Ehrman J. K., Fuller B., Pack Q. R. Exercise testing and exercise rehabilitation for patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention . 2019;39(2):65–72. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morseth B., Løchen M. L., Ariansen I., Myrstad M., Thelle D. S. The ambiguity of physical activity, exercise and atrial fibrillation. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology . 2018;25(6):624–636. doi: 10.1177/2047487318754930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yagishita A., Yamauchi Y., Sato H., et al. Improvement in the quality of life and exercise performance in relation to the plasma B-type natriuretic peptide level after catheter ablation in patients with asymptomatic persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation Journal . 2017;81(4):444–449. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-16-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudink E. A. M. P., Erkuner O., Berg J., et al. The influence of progression of atrial fibrillation on quality of life: a report from the Euro Heart Survey. EP Europace . 2018;20(6):929–934. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nourmohammadi Z., Khalifehzadeh-Esfahani A., Eftekhari M., Sanei H. The effect of aerobic physical rehabilitation on the quality of life in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation; A randomized controlled clinical trial study. ARYA Atheroscler . 2019;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.22122/arya.v15i1.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed J. L., Clarke A. E., Faraz A. M., et al. The impact of cardiac rehabilitation on mental and physical health in patients with atrial fibrillation: a matched case-control study. Canadian Journal of Cardiology . 2018;34(11):1512–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borland M., Bergfeldt L., Nordeman L., et al. Exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation improves physical fitness in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation—a randomized controlled study. Translational Sports Medicine . 2020;3(5):415–425. doi: 10.1002/tsm2.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romiti G. F., Pastori D., Rivera-Caravaca J. M., et al. Adherence to the “atrial fibrillation better care” pathway in patients with atrial fibrillation: impact on clinical outcomes-A systematic review and meta-analysis of 285,000 patients. Thrombosis & Haemostasis . 2022;122(3):406–414. doi: 10.1055/a-1515-9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Professional Committee of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation of Chinese Rehabilitation Medical Association. Chinese expert consensus on cardiac rehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi . 2021;60(2):106–116. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20200312-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included within the article.