Abstract

Introduction

Depression and antidepressants are among risk factors for osteoporosis. However, there are still inconsistencies in literature regarding bone consequences of antidepressant drugs and the role of age and the natural decline of bone health in patients with depression.

Objective

To investigate the relationship between antidepressant and bone mineral density (BMD).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and metanalysis according to PRISMA guidelines searching on PubMed/Medline, Cochrane Database, and Scopus libraries and registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021254006) using generic terms for antidepressants and BMD. Search was restricted to English language only and without time restriction from inception up to June 2021. Methodological quality was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Results

Eighteen papers were included in the qualitative analysis and five in the quantitative analysis. A total of 42,656 participants affected by different subtypes of depression were identified. Among the included studies, 10 used serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) only, 6 involved the use of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, and 2 the combined use of more than two antidepressants. No significant studies meeting the inclusion criteria for other most recent categories of antidepressants, such as vortioxetine and esketamine. Overall, we observed a significant effect of SSRI on decrease of BMD with a mean effect of 0.28 (95% CI = 0.08, 0.39).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that SSRIs are associated with a decrease of BMD. We aim to raise clinicians’ awareness of the potential association between the use of antidepressants and bone fragility to increase monitoring of bone health.

Keywords: Antidepressants (AD), Bone health, Bone mineral density (BMD), Fracture risk, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI).

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural disarray of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture.1 According to the diagnostic criteria of WHO, osteoporosis is defined as a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of -2.5 or less and osteopenia as a BMD T-score between -1 and -2.5.2 BMD, which is usually measured with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in clinical practice, correlates with fracture risk. Fractures, especially of the hip and vertebrae, are strongly associated with reductions in BMD3 and the resulting pain, inability to walk and the reduction in the quality of life carry a high risk of adverse health outcomes and mortality in older people.4 Furthermore, the direct and indirect costs of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and the resulting fractures are estimated to grow with an important economic impact worldwide.5

Depression and antidepressant drugs have been shown to be among the risk factors for osteoporosis, being associated with both low BMD and increased fracture risk.6,7 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most utilized group of antidepressants, constituting more than 60% of all antidepressants prescribed worldwide.8 SSRIs act by inhibiting the serotonin transporter to block serotonin reuptake and prolong extracellular activity.9 Interestingly, serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter have been reported in bone, begging the question whether medications that antagonize serotonin reuptake could influence bone metabolism and consequently promote drug-induced osteoporosis.10,11 A systematic review concluded that there was insufficient evidence that SSRIs and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) adversely affect bone health.12 A meta-analysis on four studies on woman concluded that antidepressants including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and SSRIs do not have any impact on BMD.13 On the contrary, other studies found an increased risk of osteoporosis and recommended to assess bone health in patients treated with SSRIs.14 Recently, Kumar et al. suggested that SSRIs may be associated with an increased fracture risk and recommended to considerer bone health when prescribing this class of drugs.15

Currently there are inconsistencies in the literature regarding bone consequences of antidepressant drugs and the role of age and the natural decline of bone health in patients with depression.

This systematic review aims to investigate the relationship between antidepressant drugs categories, including SSRIs, SNRIs and TCAs, and BMD.

Material and methods

We conducted this systematic review according to the methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration and documented the process and results in accordance with the current most updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.16 The search strategy is available in the protocol registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021254006).

Information sources and search strategy

Studies were identified searching the electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Cochrane Database, and Scopus libraries. We combined the search strategy using the search string with MeSH terms and keywords for the topics of antidepressants and bone health combined as following: (antidepressant OR tricyclic OR SSRI OR SNRI OR “Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors” OR “Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors” OR Vortioxetine OR Esketamine) AND (“risk fracture” OR fracture OR “bone mineral density” OR BMD OR bone OR osteoporosis OR osteopenia OR “bone loss” OR “bone health” OR “bone metabolism”).

Additional internet searches were also made to identify possible unpublished studies (gray literature). In addition, hand-searches of previous reviews and references of included papers were conducted for any missing eligible studies. Search was restricted to English language only and without time restriction from inception up to June 1st, 2021. All the eligible publications have been included and cited in this review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study population and study design

We included studies using any antidepressant treatment for any psychiatric condition diagnosed according to the DSM-IV, DSM IV-TR, DSM-5 or ICD-10 or -11 criteria, or validated scales with cut-off, or clinical records where the bone metabolism, osteoporosis and/or risk of fractures has been assessed or evaluated. These patients could be under chronic antidepressant treatment or be diagnosed with an early phase of disease and could be drug-naive. We excluded studies with patients who exhibited general medical, neurological comorbidity or unclear or unverified diagnoses according to the ICD criteria. We only considered studies involving a comparator group without exposure to the antidepressant.

We included all experimental and observational study designs, apart from case reports/series, including retrospective, cross-sectional or prospective design. Narrative and systematic reviews, meta-analysis, umbrella reviews, commentaries/opinion pieces, expert opinions, editorials, letters to the editor, and book chapters were excluded.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome was the evaluation of the BMD, bone metabolism and bone health in general associated to concomitant antidepressant use. Secondary outcome was the fracture risk related to the use of any antidepressants for any psychiatric condition.

Study selection and data extraction

Identified studies were independently reviewed for eligibility by two authors (MM, GS) in a two-step-based process; a first screening was performed based on title and abstract, while full texts were retrieved for the second screening. At both stages, disagreements by reviewers were resolved by consensus or involvement of a third author (RdF). Two authors (MM and GS) independently extracted data regarding sample sizes, demographic characteristics, psychopathological ratings, daily antidepressant dosages, illness duration, types of disease, and treatment duration (mean and SD) using an ad-hoc developed data extraction spreadsheet. Before data entry, values were converted to the same unit for each parameter and weighted means for covariates were computed based on means of subgroups.

Quality assessment

The same authors who performed data extraction (MM, GS) independently assessed the quality of selected studies using the modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cross-sectional studies (Table 1).17 Disagreements by reviewers were resolved by consensus or involvement of a third author (RdF).

Table 1. Quality assessment of included studies according to the Modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

| Study Author (year) | Criteria | Total | Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Agarwal et al. (2020) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Ak et al. (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| An et al. (2013) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Couturier et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Diem et al. (2007) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Diem et al. (2013) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Dubnov-Raz et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Feuer et al. (2015) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Ham et al. (2017) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Kinjo et al. (2005) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Malik et al. (2013) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Mezuk et al. (2008) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | High |

| Misra et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Moura et al. (2014) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Rauma et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Saraykar et al. (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Williams et al. (2008) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Williams et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

Based on the total score, quality was classified as “low” (0-3), “moderate” (4-6) and “high” (7-9). Criterion number (in bold): 1, representativeness of the exposed cohort; 2, selection of the nonexposed cohort; 3, ascertainment of exposure; 4, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study; 5, comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis; 6, assessment of outcome; 7, was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur?; 8, adequacy of follow up of cohorts. Each study was awarded a maximum of one or two points for each numbered item within categories, based on the Modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale rules

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with JASP open-source software (JASP, version 0.15, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands). We conducted a publication bias and adjusted meta-analysis applying a Robust Bayesian Meta-Analysis (RoBMA) method. We used a RoBMA with Competing Publication Bias Adjustment Methods18 given the potential heterogeneity related to patient populations, interventions, comparators and the inherently large variability of the outcome variables. Indeed, this method allows to correct for publication bias to give more weight to models that are better supported by data for the effect size (ES) estimation. We calculated the final pooled ES using single studies ES and population sample size (SS).

Results

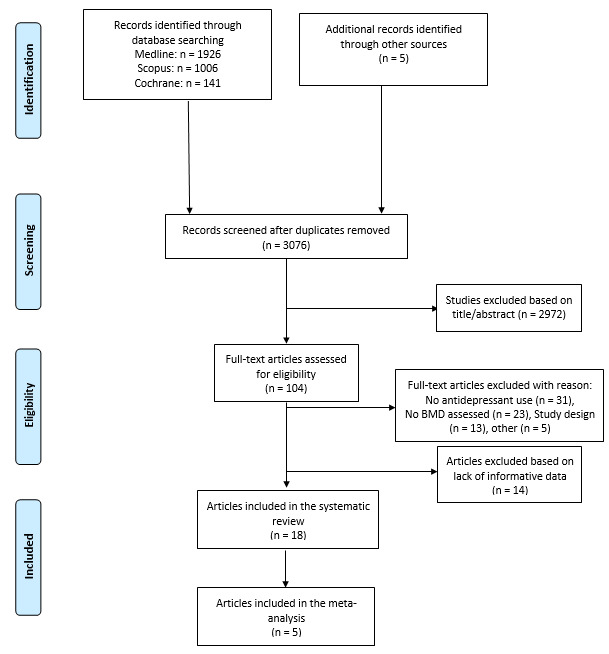

Initially, 3,076 items were identified among database and authors’ search, of which 2,972 articles were excluded in the title/abstract screening phase because they did not fulfill inclusion criteria. The full text of the remaining 104 articles were reviewed. Overall, 31 out of 104 articles were removed because they did not involve antidepressants, 23 because did not assess BMD, 13 because were editorials, letters to editors, reviews, meta-analyses, or case reports, and 5 for other reasons. Then, 14 manuscripts of the remaining 32 papers were excluded because they did not fulfill the criteria for inclusion, while the remaining 18 were included in the qualitative analysis and 5 in the quantitative analysis (Figure 1).14,19–35

Figure 1. Literature review and PRISMA flow diagram.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

Characteristics of included studies and participants

Characteristics of included studies and their participants are summarized in Table 1. The studies were carried out all over the world, counting Australia, United States of America (USA), Holland, Canada, Japan, Finland, Austria, Turkey, Israel, Korea, and are being published between 2005 and 2020. Briefly, the 18 studies included in this analysis contained data from 42,656 participants affected by different subtypes of depression. Among the included studies, 10 used SSRIs only, 6 involved the use of SSRIs and TCAs, and 2 the combined use of more than two antidepressants. However, no studies using other types of antidepressants have been identified. The studies enrolled patients of all ages, ranging from teenagers (under 18 years old) and young adults (18-35) to adults (36-64) and the elderly (over 65). The gender ratio has only been expressed by a small proportion of studies, and it tends to always be in favor of women. While the BMD, expressed in g/cm2, was reported for both case and control groups, with various differences in values in 10 studies. The BMD has been evaluated in several very different areas, including femoral neck, lumbar spine, total femur, trochanter, total body, distal forearm, mid-forearm, and tibia. The follow-up period reported in the included studies ranges from a minimum of 3 months to a maximum of 204 months. Table 2 and Table 3 show main extracted data of included studies.

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies providing T-score or Z-score (n. 6).

| Authors, year | Country | Study design | Antidepressant | Sample Size | Age of patients (mean ± SD) | Age of controls (mean ± SD) | Gender (M:F) | BMD investigation bone site | T-score main cohort (mean ± SD) | Control Group T-score (mean ± SD) | Z-score main cohort (mean ± SD) | Control Group Z-score (mean ± SD) | p | Follow-up (months) |

| Ak,2015 | Turkey | Prospective cohort study | Paroxetine | 100 | 55,0 ± 0,6 | 56,5 ± 4,2 | 0:60 | lumbar spine | -0,5 ± 1,9 | -1,4 ± 2,3 | -0,4 ± 0,6 | 0,05 ± 1,5 | N/A | 12 |

| femoral neck | 0,3 ± 0,5 | -0,5 ± 1,3 | 0,4 ± 0,5 | 0,4 ± 1,4 | ||||||||||

| Sertraline | 56,9 ± 3,2 | lumbar spine | -0,6 ± 2,2 | -0,1 ± 1,1 | N/A | |||||||||

| femoral neck | 0,3 ± 0,5 | 0,4 ± 0,9 | ||||||||||||

| Citalopram | 56,2 ± 2,6 | lumbar spine | -0,7 ± 2 | -0,4 ± 2,1 | ||||||||||

| femoral neck | -0,9 ± 0,3 | -0,8 ± 0,5 | ||||||||||||

| An,2013 | Korea | Retrospective cohort study | SSRI | 85 | 68,4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | -2,8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24 |

| Couturier,2013 | Canada | Retrospective cohort study | SSRI | 62 | 16,2 ± 1,1 | 16,0 ± 1,0 | 0:31 | N/A | N/A | N/A | -1,1 ± 1,1 | -0,5 ± 1,3 | N/A | 14 |

| Dubnov-Raz,2012 | Israel | Case-control study | SSRI | 80 | 34 ± 5,0 | 32,4 ± 5,2 | 22:18 | N/A | N/A | N/A | -0,29 ± 0,89 | -0,07 ± 0,83 | N/A | N/A |

| Malik,2013 | Austria | Cross-sectional study | SSRI | 87 | 43,5 ± 10,3 | N/A | N/A | lumbar spine | N/A | N/A | -0,3 ± 1,15 | 0,22 ± 1,27 | N/A | 60 |

| femoral neck | -0,19 ± 1,05 | 0,09 ± 0,88 | ||||||||||||

| Total hip | 0,08 ± 0,84 | 0,18 ± 0,85 | ||||||||||||

| Misra,2010 | USA | Cohort study | SSRI | 155 | 17 ± 2,3 | 16,6 ± 1,8 | 0:60 | lumbar spine | N/A | N/A | -0,83 ± 0,82 | -1,16 ± 1,05 | N/A | <6 |

| 17,9 ± 2,1 | hip | -0,45 ± 0,73 | -0,67 ± 0,94 | |||||||||||

| femoral neck | -0,59 ± 0,79 | -0,81 ± 1,03 | ||||||||||||

| whole body | -0,17 ± 0,90 | -0,49 ± 1,03 | ||||||||||||

| lumbar spine | -1,70 ± 0,77 | >6 | ||||||||||||

| hip | -1,31 ± 0,91 | |||||||||||||

| femoral neck | -1,35 ± 0,83 | |||||||||||||

| whole body | -0,85 ± 1,07 |

F: female; M: male; N/A: Not available; SD: standard deviation; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies providing the bone mineral density (BMD) (n. 12).

| Authors, year | Country | Study design | Antidepressant | Sample Size | Age of patients (mean ± SD) | Age of controls (mean ± SD) | Gender (M:F) | BMD investigation bone site | BMD main group (g/cm2) | BMD controls group (g/cm2) | p | Follow-up (months) |

| Agarwal,2020 | USA | Cross sectional cohort study | SSRI SNRI TCA | 195 | 75,7 ± 5,2 | 76,5 ± 6,3 | N/A | lumbar spine | 0,998 ± 0,052** | 1,0148 ± 0,039** | <0,05 | N/A |

| femoral neck | 0,137 ± 0,039** | 0,1272 ± 0,027** | <0,05 | |||||||||

| radius | 0,7666 ± 0,078** | 0,8047 ± 0,066** | <0,05 | |||||||||

| Diem,2007 | USA | Cohort study | TCA | 2722 | 78,6 ± 3,3 | 78,4 ± 3,7 | N/A | total hip | 0,76 ± 0,13 | 0,76 ± 0,14 | 0,99 | 60 |

| SSRI | 0,74 ± 0,15 | 0,02 | ||||||||||

| Diem,2013 | USA | Prospective cohort study | SSRI | 1972 | 49,6 ± 4,5 | 49,7 ± 3,9 | N/A | lumbar spine | 1,07 ± 0,16 | 1,05 ± 0,15 | 0,07 | 12 |

| femoral neck | 0,86 ± 0,14 | 0,82 ± 0,13 | < 0,002 | |||||||||

| total hip | 0,99 ± 0,15 | 0,94 ± 0,14 | < 0,001 | |||||||||

| TCA | 49,7 ± 4,5 | lumbar spine | 1.06 ± 0,15 | N/A | 0.07 | |||||||

| femoral neck | 0.83 ± 0,13 | < 0,002 | ||||||||||

| total hip | 0.95 ± 0,14 | < 0,001 | ||||||||||

| Feuer,2015 | USA | Cross-sectional study | SSRI | 4303 | 16,1 ± 2,4 | 15,7 ± 2,4 | N/A | lumbar | 0,92 ± 0,02 | 0,95 ± 0,01 | 0,09 | 60 |

| total femur | 0,93 ± 0,02 | 0,99 ± 0,01 | 0,016 | |||||||||

| femoral neck | 0,86 ± 0,02 | 0,91 ± 0,0 | 0,045 | |||||||||

| Ham,2017 | Netherlands | Cohort study | SSRI | 10746 | 64,1 ± 8,7 (M) | N/A | 4915:5831 | N/A | 0.004* | N/A | 0.598 (M) | 204 |

| 65,8 ± 8,7 (W) | 0.002* | 0.209 (W) | ||||||||||

| TCA | 0.007* | 0.848 (M) | ||||||||||

| 0.005* | 0.427 (W) | |||||||||||

| Kinjo,2005 | Japan | Cross-sectional study | SSRI TCA | 14646 | 54,3 ± 15,2 | 48,1 ± 19,0 | N/A | 0,95 | 0,95 | N/A | N/A | |

| Mezuk,2008 | USA | Cohort study | SSRI TCA | 98 | 71,5 ± 6,6 | N/A | 22:66 | lumbar spine | 1,17 (M) | 1,21 (M) | N/A | N/A |

| 0,88 (F) | 1,12 (F) | |||||||||||

| Moura,2014 | Canada | Prospective cohort study | SSRI SNRI | 4011 | 63,65 ± 8 | 63,43 ± 7,9 | N/A | total hip | 0,86 ± 0,14 | 0,90 ± 0,15 | N/A | 120 |

| lumbar spine | 0,94 ± 0,17 | 0,96 ± 0,18 | ||||||||||

| femoral neck | 0,71 ± 0,12 | 0,73 ± 0,12 | ||||||||||

| Rauma,2016 | Finland | Cohort study | SSRI TCA Other | 1988 | 63,6 ± 2,9 | 63,7 ± 2,8 | N/A | N/A | 0,8842 ± 0,13 | 0,8805 ± 0,12 | 0,031 | 60 |

| Saraykar,2017 | USA | Cross-sectional retrospective study | SSRI | 140 | 78,1 ± 10,5 | 77,4 ± 9,8 | N/A | femoral neck | 0,776 ± 0,031 | 0,771 ± 0,13 | 0,92 | 56 |

| spine | 1,038 ± 0,051 | 1,099 ± 0,022 | 0,393 | |||||||||

| Williams,2008 | Australia | Community-based study | SSRI | 128 | 57,5 ± 5,1 | 51,0 ± 4,8 | N/A | lumbar spine | 1,181 ± 0,163 | 1,228 ± 0,161 | 0,18 | 60 |

| femoral neck | 0,897 ± 0,143 | 0,964 ± 0,151 | 0,05 | |||||||||

| ward's triangle | 0,780 ± 0,163 | 0,831 ± 0,161 | 0,15 | |||||||||

| trochanter | 0,789 ± 0,143 | 0,816 ± 0,132 | 0,35 | |||||||||

| total body | 1,176 ± 0,100 | 1,187 ± 0,086 | 0,57 | |||||||||

| distal forearm | 0,324 ± 0,053 | 0,336 ± 0,056 | 0,32 | |||||||||

| mid-forearm | 0,696 ± 0,081 | 0,733 ± 0,075 | 0,03 | |||||||||

| Williams,2018 | Australia | Cohort study | SSRI | 1138 | 68 ± 6,5 | 61 ± 7,7 | N/A | femoral neck | 0,93 ± 0,17 | 0,99 ± 0,15 | 0,03 | 3 |

F: female; M: male; N/A: Not available; SD: standard deviation; *: mean difference; ** volumetric bone mineral density (milligrams/cubic centimeters); SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; TCA: tricyclic antidepressants.

Among the included studies, 7 reported a statistically significant difference in BMD reduction between the antidepressant exposed group and the control group. On the other hand, two papers found a clear tendency for BMD levels to decrease in the group of patients exposed to antidepressants, but without reaching statistical significance. Finally, 9 studies did not report a level of significance between groups. Regarding bone health, 12 studies reported bone density data through BMD, while 3 reported as T-score and 3 as Z-score.

Analysis of pooled effect

After dividing the studies by type of antidepressant used, analytical methods, comparators, outcome, study design, bone site and BMD evaluation method, we found only 5 comparable studies in terms of characteristics.24–27,32

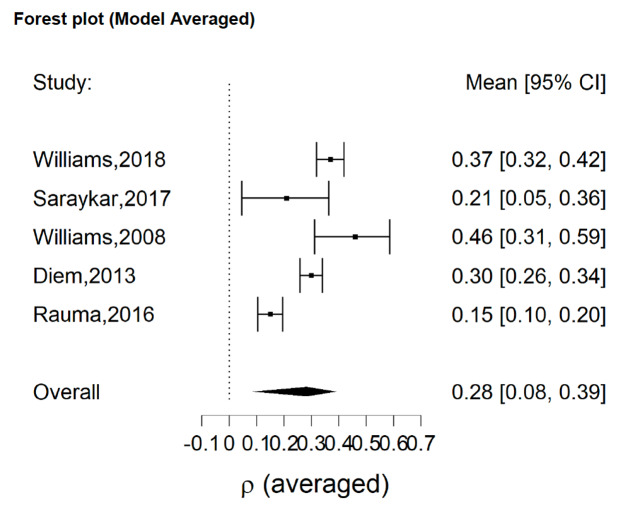

All five included studies had a significant single ES according to our analysis, with a minimum estimated effect of 0.15 (95% CI = 0.10, 0.20)24 and a maximum estimated effect of 0.46 (95% CI = 0.31, 0.59).27 Overall, we observed a significant effect of SSRI on decrease of BMD with a mean effect of 0.28 (95% CI = 0.08, 0.39) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Analysis of pooled effect of SSRI on decrease of BMD with a mean effect of 0.28 (95% CI = 0.08, 0.39).

Discussion

Considering the high worldwide use of antidepressants both in quantitative and qualitative terms, it may be desirable to increase clinicians’ awareness of their efficacy and tolerability, in order to have the largest possible knowledge of their risks and benefits, with the clinical goal to use them appropriately.36 This systematic review with meta-analysis for the first time provides evidences about the correlation between all antidepressant types use and BMD, greatly reinforcing the idea of a biological implication of antidepressants in bone turnover.37

Our search identified results mainly for SSRIs, with a little portion for SNRI and TCAs, finding no significant studies meeting the inclusion criteria for other most recent categories of antidepressants, such as vortioxetine and esketamine. This could be due to a shorter availability time to study more recently accessible drugs; moreover, it could be linked to the different mechanism of action, without a direct influence on bone metabolism.6,38 However, it is desirable that these hypotheses will be confirmed by future studies in the field.

In this regard, a large case-control study conducted in Denmark on 124,655 fracture cases and 373,962 age- and gender-matched controls examined the exposure to various antidepressants of all categories and a number of confounders on the risk of fractures, finding an increased risk only for SSRIs and TCAs, but not for vortioxetine, mirtazapine, reboxetine or other.39 This could also partly explain why over the years it has been chosen not to pursue further the analysis of these categories and we have not identified eligible studies.

In a previous systematic review, Gebara et al. highlighted that a close correlation between depression and reduction in bone density is recognized, with a consequent increased risk of fracture, but, according to the authors, the pathophysiological basis of this evidence is still far to be totally understood.37 Indeed, the authors suspect that the use of antidepressants is at the basis of the increased risk, but the evidence in this regard is not sufficient, thus calling for more in-depth research in this regard.37 On the contrary, the negative impact of SSRIs on bone health is extensively studied and supported by many evidence of efficacy both in vitro and in vivo, and by numerous literature tests, which also represents the theoretical basis of our review.6,40

A previous systematic review with meta-analysis, investigated the effect of antidepressants on BMD, however limiting the analysis to SSRIs only and not to all categories of antidepressants.41 The authors included 11 studies involving the use of SSRIs and the evaluation of BMD on the lumbar spine, the total hip and femoral neck concluding that the use of SSRIs was significantly associated with lower BMD values (SMD - 0.40; 95% CI - 0.79 to 0.00; p = 0.05) and BMD Z-scores (SMD - 0.28; 95% CI - 0.50 to - 0.05; p = 0.02) of the lumbar spine, especially in elderly.41 These findings, while differentiating for the most affected site, confirm an important role of SSRIs in bone metabolism with a significant worsening of BMD. A further meta-analysis focused on the association between the use of antidepressants and fracture risk, suggesting that SSRIs may be associated with an increased fracture risk.15 This conclusion was also confirmed by similar studies on anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders, which are per se populations at high-risk of fracture even in the absence of an antidepressants use.42,43

A large and recent cohort study conducted by Coupland and colleagues on 60,746 patients over 65 enrolled at 570 general practices in the United Kingdom demonstrated how all classes of antidepressant drug were associated with significantly increased risks of all-cause mortality, attempted suicide/self-harm, falls, fractures, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding.44 In particular, the fracture risk was higher with SSRIs, TCAs or other antidepressants by 1.58, 1.26 and 1.64 times, respectively, compared to no users. Nevertheless, the data must also be read in consideration of the overall increased risk of falls in the population and with the bias of no direct BMD evaluation. However, it is interesting to note that the use of the antidepressant increased the risk of fracture, and this could be interpreted as a possible long-term clinical result of the drug’s action on BMD. This is comparable with our results, where the observed decrease of the BMD in the SSRI users’ group is likely to contribute to an altered bone turnover with a mismatch between bone formation and resorption resulting in an overall bone loss. Our findings are in line with previous results from similar studies and they support also previous observations suggesting that SSRI use may be associated with low BMD and increased secondary long-term fracture risk.

Limitations

We acknowledge that the results of our meta-analysis suffer from some limitations as well as they are characterized by some peculiarities and strengths. First, we found only studies using SSRIs, SNRIs and TCAs, both with single and mixed agents, but no studies involving vortioxetine or esketamine or other newest antidepressants were identified, although present in the search string. Second, the great heterogeneity of the data we found in the selected studies prevented us from conducting a comprehensive quantitative analysis between them, thus reducing the final number of studies, and therefore of patients, comparable to each other. In this regard, we did not find a granularity of information that would allow us to consider specific groups of patients divided by age, gender, duration of drug intake and observation or particular risk factors. Third, the small number of studies included, and the paucity of data found in the literature avoided us from drawing definitive conclusions, which therefore remain only plausible and should be confirmed by further prospective studies designed specifically for this purpose. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the correlation between all antidepressant categories and BMD. Indeed, we did not restrict the search to a precise antidepressant category or psychiatric disorder in particular. Moreover, the obtained results, both in the qualitative and in the quantitative analysis, have a certain internal consistency and support more what has already been demonstrated by previous similar studies on the same topic.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that SSRIs are associated with a decrease of BMD. We aim to raise clinicians’ awareness of the potential association between the use of antidepressants and bone fragility to increase monitoring of bone health.

Authors’ contributions

Each author fulfils each of the authorship requirements.

MM designed the study, performed data collection and interpretation, wrote the paper, and drafted the final manuscript as submitted; RdF designed the study, performed data collection, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, wrote the paper, and drafted the final manuscript as submitted; GS performed data collection and interpretation, and wrote the paper; PDF contributed to the interpretation and analysis of data, and wrote the paper; CSG coordinated data collection and statistical analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript; OG conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript; GG conceptualized and designed the study, performed data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript as submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding Statement

The authors declare that no funding was received to perform this study.

References

- 1. Consensus development conference: Diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993;94(6):646-650. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(93)90218-e [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: Synopsis of a WHO report. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4(6):368-381. doi:10.1007/bf01622200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1254-1259. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Compston JE, McClung MR, Leslie WD. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2019;393(10169):364-376. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32112-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Cauley JA. Public Health Impact of Osteoporosis. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1243-1251. doi:10.1093/gerona/glt093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, Berk M, Williams LJ. Effects of Depression and Serotonergic Antidepressants on Bone: Mechanisms and Implications for the Treatment of Depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0323-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. Williams LJ, Pasco JA, Jacka FN, Henry MJ, Dodd S, Berk M. Depression and Bone Metabolism. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(1):16-25. doi:10.1159/000162297 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Pirraglia PA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. Trends in Prescribing of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Other Newer Antidepressant Agents in Adult Primary Care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;05(04):153-157. doi:10.4088/pcc.v05n0402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Vaswani M, Linda FK, Ramesh S. Role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in psychiatric disorders: A comprehensive review. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(1):85-102. doi:10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00338-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Bliziotes M. Update in Serotonin and Bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4124-4132. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Hodge JM, Wang Y, Berk M, et al. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors Inhibit Human Osteoclast and Osteoblast Formation and Function. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):32-39. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. Gebara MA, Lipsey KL, Karp JF, Nash MC, Iaboni A, Lenze EJ. Cause or Effect? Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Falls in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(10):1016-1028. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Schweiger J, Schweiger U, Hüppe M, et al. The Use of Antidepressive Agents and Bone Mineral Density in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1373. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Moura C, Bernatsky S, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Antidepressant use and 10-year incident fracture risk: The population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMoS). Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1473-1481. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2649-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Kumar M, Bajpai R, Shaik AR, Srivastava S, Vohora D. Alliance between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fracture risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(10):1373-1392. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-02893-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. Published online March 29, 2021:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):154. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Bartoš F, Maier M, Stanley EJ, Wagenmakers H, Doucouliagos TD. No Need to Choose: Robust Bayesian Meta-Analysis with Competing Publication Bias Adjustment Methods. PsyArXiv Prepr. Published online 2021.

- 19. Agarwal S, Germosen C, Kil N, et al. Current anti-depressant use is associated with cortical bone deficits and reduced physical function in elderly women. Bone. 2020;140:115552. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2020.115552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. Kinjo M, Setoguchi S, Schneeweiss S, Solomon DH. Bone mineral density in subjects using central nervous system-active medications. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1414.e7-1414.e12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Malik P, Gasser RW, Moncayo RC, et al. Bone mineral density and bone metabolism in patients with major depressive disorder without somatic comorbidities. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2013;44:58-63. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Golden SH, Wand G, Lee HB. Depression, Antidepressants, and Bone Mineral Density in a Population-Based Cohort. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(12):1410-1415. doi:10.1093/gerona/63.12.1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. Misra M, Le Clair M, Mendes N, et al. Use of SSRIs May Impact Bone Density in Adolescent and Young Women With Anorexia Nervosa. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(9):579-586. doi:10.1017/s1092852900000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Rauma PH, Honkanen RJ, Williams LJ, Tuppurainen MT, Kröger HP, Koivumaa-Honkanen H. Effects of antidepressants on postmenopausal bone loss — A 5-year longitudinal study from the OSTPRE cohort. Bone. 2016;89:25-31. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Saraykar S, John V, Cao B, Hnatow M, Ambrose CG, Rianon N. Association of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Bone Mineral Density in Elderly Women. J Clin Densitom. 2018;21(2):193-199. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Williams LJ, Berk M, Hodge JM, et al. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Markers of Bone Turnover in Men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2018;103(2):125-130. doi:10.1007/s00223-018-0398-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27. Williams LJ, Henry MJ, Berk M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and bone mineral density in women with a history of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(2):84-87. doi:10.1097/yic.0b013e3282f2b3bb [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28. Ak E, Bulut SD, Bulut S, et al. Evaluation of the effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: An observational cross-sectional study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(1):273-279. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2859-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29. An KY, Shin WJ, Lee KJ. The Necessity of Bone Densitometry for Patients Taking Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. J Bone Metab. 2013;20(2):95. doi:10.11005/jbm.2013.20.2.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Couturier J, Sy A, Johnson N, Findlay S. Bone Mineral Density in Adolescents With Eating Disorders Exposed to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Eat Disord. 2013;21(3):238-248. doi:10.1080/10640266.2013.779183 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31. Diem SJ. Use of Antidepressants and Rates of Hip Bone Loss in Older Women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1240. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.12.1240 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32. Diem SJ, Ruppert K, Cauley JA, et al. Rates of Bone Loss Among Women Initiating Antidepressant Medication Use in Midlife. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4355-4363. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Dubnov-Raz G, Hemilä H, Vurembrand Y, Kuint J, Maayan-Metzger A. Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and neonatal bone density. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(3):191-194. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Feuer AJ, Demmer RT, Thai A, Vogiatzi MG. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and bone mass in adolescents: An NHANES study. Bone. 2015;78:28-33. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35. Ham AC, Aarts N, Noordam R, et al. Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Bone Mineral Density Change. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(5):524-530. doi:10.1097/jcp.0000000000000756 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357-1366. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Gebara MA, Shea MLO, Lipsey KL, et al. Depression, Antidepressants, and Bone Health in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1434-1441. doi:10.1111/jgs.12945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Faquih AE, Memon RI, Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Naveed S. A Review of Novel Antidepressants: A Guide for Clinicians. Cureus. Published online March 6, 2019. doi:10.7759/cureus.4185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39. Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Other Antidepressants and Risk of Fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82(2):92-101. doi:10.1007/s00223-007-9099-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40. Tsapakis EM, Gamie Z, Tran GT, et al. The adverse skeletal effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(3):156-169. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41. Zhou C, Fang L, Chen Y, Zhong J, Wang H, Xie P. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1243-1251. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4413-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42. Solmi M, Veronese N, Correll CU, et al. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and fractures among people with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(5):341-351. doi:10.1111/acps.12556 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43. Robinson L, Aldridge V, Clark EM, Misra M, Micali N. Pharmacological treatment options for low Bone Mineral Density and secondary osteoporosis in Anorexia Nervosa: A systematic review of the literature. J Psychosom Res. 2017;98:87-97. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44. Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343(aug02 1):d4551-d4551. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]