Abstract

Purpose

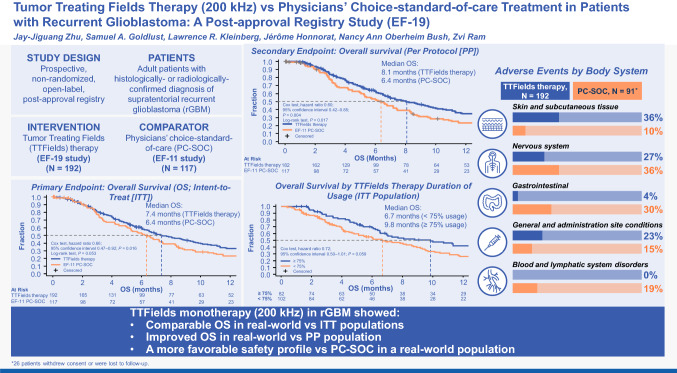

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy, a noninvasive, anti-mitotic treatment modality, is approved for recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM) and newly diagnosed GBM based on phase III, EF-11 (NCT00379470) and EF-14 (NCT00916409) studies, respectively. The EF-19 study aimed to evaluate efficacy and safety of TTFields monotherapy (200 kHz) vs physicians’ choice standard of care (PC-SOC; EF-11 historical control group) in rGBM.

Methods

A prospective, post-marketing registry study of adults with supratentorial rGBM treated with TTFields therapy was conducted. Primary endpoint was overall survival (OS; intent-to-treat [ITT] population) and secondary endpoint was OS per-protocol (PP). Subgroup and toxicity analyses were conducted.

Results

Median OS (ITT population) was comparable with TTFields monotherapy vs PC-SOC (7.4 vs 6.4 months, log-rank test P = 0.053; Cox test hazard ratio [HR] [95% CI], 0.66 [0.47–0.92], P = 0.016). The upper-bound HR (95% CI) was lower than pre-defined noninferiority (1.375 threshold). In the PP population, median OS was significantly longer for TTFields monotherapy vs PC-SOC (8.1 vs 6.4 months; log-rank test P = 0.017; Cox test HR [95% CI], 0.60 [0.42–0.85], P = 0.004). TTFields therapy showed increased benefit with extended use (≥ 18 h/day [averaged over 28 days]). TTFields therapy-related adverse events (AEs) by body system were lower vs PC-SOC: mainly mild-to-moderate skin AEs.

Conclusion

In the real-world setting, TTFields monotherapy showed comparable (ITT population) and superior (PP population) OS vs PC-SOC in rGBM. In line with previous results, TTFields therapy showed a favorable safety profile vs chemotherapy, without new safety signals/systemic effects.

Trial registration: NCT01756729, registered December 20, 2012.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-022-00555-5.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM; grade-IV isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 [IDH1] wildtype glioma [1, 2]) is the most common locally invasive and aggressively infiltrative primary malignant brain tumor [3–6], making total resection implausible.

Historically, standard adjuvant therapy in newly diagnosed GBM (ndGBM) has been based on the Stupp protocol, comprising maximal safe resection/biopsy, followed by radiation therapy [RT] with concomitant and 6–12 months maintenance temozolomide (TMZ) [7].

In contrast, optimal management of patients with recurrent GBM (rGBM) has traditionally been less well defined. Recommended treatment options include craniotomy with/without carmustine implant, laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) [8], stereotactic radiosurgery [9], or salvage RT followed by systemic therapy [10], (i.e., TMZ [11], nitrosoureas [e.g., carmustine or lomustine] [12, 13], and bevacizumab [14]). However, once tumors progress after first-line therapy, treatment options are limited and results are often unsatisfactory, making management of rGBM a considerable challenge [15].

Tumor Treating Fields therapy (TTFields, Optune®; Novocure.® GmbH; device manufacturer) is a first-in-class, noninvasive, loco-regional cancer treatment approved for use in ndGBM, rGBM and malignant pleural mesothelioma [16, 17]. TTFields are electric fields generated by a portable medical device that is designed to be integrated into daily life, while maintaining patients’ quality of life, and delivered via scalp-placed arrays [2, 18]. TTFields work by disrupting normal localization and function of polar components within cells, and specifically target cancer cells due to characteristics that distinguish them from healthy cells and tissue [19–24]

Since its approval in the European Union (EU), US, Japan, and China [16, 25–28], TTFields therapy concomitant with maintenance TMZ has been incorporated into the GBM treatment paradigm, expanding treatment options for this patient population with high unmet needs. Additionally, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend TTFields therapy (category 1 recommendation) for adult patients with ndGBM [29, 30].

Results from the EF-14 (NCT00916409) study formed the basis for approval for use in ndGBM. EF-14 demonstrated significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) for TTFields therapy concomitant with TMZ (6.7 months) vs TMZ alone (4.0 months) and a significantly improved overall survival (OS) for TTFields therapy concomitant with TMZ (20.9 months) vs TMZ alone (16.0 months) [31]. Additionally, 5-year OS rates were more than double that of TMZ alone (5% vs 13%; P = 0.04) [31].

Additionally, the EF-11 study, in which TTFields therapy was compared with best standard of care (SOC) in patients with rGBM, also showed improvements in outcomes and formed the basis for approval in rGBM [32]. TTFields therapy has also shown clinical efficacy in a range of other solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, liver, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer, when used concomitantly with systemic therapies and alongside radiation [33–38]. Clinical and real-world data demonstrate that TTFields therapy has a favorable safety profile, characterized by a low rate of systemic adverse events (AEs) compared with chemotherapeutic regimens. AEs related to TTFields therapy are predominantly dermatologic in nature and can be managed with appropriate prophylaxis and intervention [31, 32, 39–41].

Here we report the results of a prospective, open-label, multi-site, post-marketing registry study of patients with rGBM treated with TTFields monotherapy (200 kHz), evaluating efficacy and safety vs the physicians’ choice SOC (PC-SOC) EF-11 study cohort arm (historical control group).

Methods

Study design

The EF-19 (NCT01756729) study was a prospective, open-label, multi-site, post-marketing registry study designed to compare the efficacy and safety of TTFields monotherapy in patients with rGBM to PC-SOC (historical control group) from the EF-11 study. The recruitment period was approximately 24 months and follow-up period was 12 months from last patient recruited. Patient follow-up was conducted according to standard practices at each participating center; evaluation of AEs, vital signs, and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) (where available) were performed at each follow-up appointment. Patients were also seen by a Novocure-trained Device Support Specialist (DSS) once per month during follow-up.

Study population

The treatment population was comprised of patients already enrolled in the PRiDe registry (which includes all patients in the US treated with TTFields therapy, commercially), therefore, patients were recruited to this study from either the outpatient clinic or inpatient hospital setting at any certified TTFields therapy center in the US. All patients provided written consent for use of their data in the registry, including protected health information.

Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the supplementary material. Adult patients (≥ 22 years of age) with a histologically or radiologically confirmed diagnosis of supratentorial rGBM, per Macdonald’s criteria [25] with KPS score of ≥ 70 enrolled in the PRiDe registry were eligible. The control arm comprised patients from the PC-SOC cohort of the EF-11 study [32].

Study treatment

Continuous TTFields (200 kHz) were generated using the NovoTTF-100A system and delivered for ≥ 18 h/day, for a minimum of 4 weeks, through scalp-placed arrays which remained in place during treatment (arrays could be removed during treatment breaks and during routine array changes). Patients carried/wore the field generator and battery in a bag connected to the arrays whilst receiving treatment, as these components are essential for the generation of TTFields. Before TTFields therapy was initiated, patients/caregivers were provided with education and training on TTFields therapy usage by certified physician/nurse staff. To educate patients and caregivers on operating the device independently, access to a designated DSS (service by device manufacturer, Novocure®) and hotline assistance (24 h/day) were provided to patients for additional technical support. All treatment was delivered on an outpatient basis. Arrays were supplied in individual sterile packages for hygienic application. Array changes (~ twice per week) were conducted by patient, caregiver(s), and/or a DSS. TTFields therapy continued until clinical disease progression (new central nervous system symptoms/worsening of symptoms and significant radiological tumor growth), development of significant/serious AEs or patient withdrawal.

Assessments and outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was OS (months) from time of treatment initiation in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, evaluating noninferiority of TTFields monotherapy vs PC-SOC. The key additional endpoint was OS (months) in the per-protocol (PP) population, evaluating noninferiority vs PC-SOC. Furthermore, the additional endpoint of median time to treatment failure (months), defined as time from treatment start to treatment discontinuation, in patients treated with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC was assessed in the ITT population, serving as a surrogate measure for progressive disease (PD). Other additional endpoints in the ITT population included incidence of AEs and OS according to O[6]-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation and IDH1 gene mutation statuses in the ITT population. PD was not evaluated as an EF-19 endpoint and served as a guide to assess any needs for treatment cessation of TTFields therapy.

AE information was collated during the study period from unsolicited patient/caregiver/investigator reports, during interactions with DSS/prescribers, and from nCompass™ support emails, and was processed according to routine post-market surveillance activities from the manufacturer. AEs were classified using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities dictionary version 22.1 (MedDRA v22.1). Due to the nature of this registry, AE severity could only be classified as non-serious or serious.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS), version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

A sample size of 192 patients in the TTFields arm (including estimated 10% loss to follow-up rate) was determined, based on a noninferiority log-rank test with a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 80%, comparing time to event (i.e., death) in patients treated with TTFields therapy and PC-SOC. The sample size analysis was performed using NCSS-PASS 11 16.0 (NCSS, Kaysville, UT, USA). The null hypothesis was that the hazard-of-death would be higher for TTFields monotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] > 1.375); and alternative hypothesis HR would be ≤ 1.375. An HR of 0.1083 with PC-SOC was estimated from the rate-of-death per month in the PC-SOC arm. For OS analyses, patients without a known date of death were censored at last known date documented alive. Analyses were conducted under the assumptions that the active treatment and control arms had equivalent background characteristics, and that treatments were applied contemporaneously, even when they were not.

Additional analyses of annual OS rates were compared between groups, using a 1-sided Z distribution of the Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS rates at the defined timepoint. Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze OS, controlling for treatment group, age, sex, KPS and type of rGBM resection. Threshold for significant interactions was specified at an alpha of 0.05.

The ITT population included all enrolled patients from the TTFields therapy and historical control arms. The PP population included patients who received ≥ 28 days of TTFields monotherapy for ≥ 18 h/day (on average in the first month of treatment) and all PC-SOC patients who received systemic therapy.

Results

Baseline characteristics and patient disposition

Overall, 1082 patients with rGBM who received TTFields monotherapy in the US clinical-practice setting from February 10, 2016 to December 28, 2017 were screened for eligibility. Of these, 192 patients met preset EF-19 registry study inclusion criteria for enrolment at TTFields therapy-certified US sites. Patients were enrolled and cared for by 151 unique certified US-site physicians. The control arm included 117 patients from the PC-SOC cohort of the EF‐11 study.

Key baseline characteristics were comparable between groups, including age, sex, KPS score, and extent of surgical resection at diagnosis (Table 1). Of patients who had available tissue samples (84/192 [44%] patients in the TTFields therapy arm) for genomic evaluation, 42% had MGMT promoter methylation. Data on MGMT and IDH1 status were not collected in the EF-11 study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and patient disposition in TTFields therapy EF-19 registry and EF-11 PC-SOC arms

| Baseline characteristics and patient disposition | TTFields therapy EF-19 Registry (N = 192) |

PC-SOC EF-11 (N = 117) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (min–max) years of age | 57.0 (23–80) | 54.0 (29–74) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 125 (65) | 73 (62) |

| Female | 67 (35) | 44 (38) |

| KPS score, n (%) | 129 (67) | 114 (97) |

| Median (min–max) | 80.0 (70–100) | 80.0 (50–100) |

| Race, n (%) | 164 (85) | 117 (100) |

| White | 141 (73) | 106 (91) |

| African American | 9 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Asian | 6 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Hispanic | 8 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Extent of initial resection, n (%) | 189 (98) | NA |

| Biopsy | 15 (8) | NA |

| Partial resection | 44 (23) | NA |

| Gross total resection | 130 (69) | NA |

| Extent of resection at time of recurrence, n (%) | 183 (95) | 117 (100) |

| None | 106 (55) | 88 (75) |

| Biopsy | 4 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Partial resection | 10 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Gross total resection | 63 (33) | 26 (22) |

| MGMT promoter methylation status, n (%) | 84 (44) | NA |

| MGMT promoter methylation status | 35 (42) | NA |

| No MGMT promoter methylation status | 49 (58) | NA |

| IDH1 gene status, n (%) | 93 (48) | NA |

| Mutated IDH1 gene status | 16 (17) | NA |

| Wild-type IDH1 gene status | 77 (83) | NA |

| Number of prior-chemotherapy lines, n (%) | 190 (99) | NA |

| Median (min–max) | 2 (0–7) | NA |

| 0 | 4 (2) | NA |

| 1 | 96 (51) | NA |

| 2 | 60 (32) | NA |

| 3 | 20 (11) | NA |

| > 3 | 10 (5) | NA |

| Steroid usage, n (%) | 85 (44) | 44 (38) |

| Anticonvulsant usagea, n (%) | 142 (74) | 50 (43) |

| ITT population, N (%) | 192 (100) | 117 (100) |

| Remained on treatment at study closure, n (%) | 8 (4) | NA |

| Treatment discontinuations, n (%) | 184 (96) | NA |

| Due to deathb | 134 (70) | NA |

| Other reasonsc | 50 (26) | NA |

| PP populationd, N (%) | 182 (95) | 117 (100) |

Percent values have been rounded to nearest integer

“NA” represents variables that were not collected in the EF-11 clinical study, therefore no comparable data are available [32]

ITT intent-to-treat; IDH1 isocitrate dehydrogenase 1; KPS Karnofsky Performance Status; MGMT O6-Methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase; MRI magnetic resonance imaging; NA not available; PC-SOC physicians’ choice standard of care; PD progressive disease; PP per-protocol; TTFields Tumor Treating Fields

aAnticonvulsant use, during the EF-11 study, was recorded by study teams using clinical case report forms. In the post-approval EF-19 registry study, recording was done using patient charts. Any evidence of anticonvulsant use in the charts of each registry patient was recorded, as it was not possible to determine start and stop dates. Therefore, the number of patients noted in the TTFields therapy EF-19 registry arm does not reflect patients who used anticonvulsants at baseline, but rather the number of patients with any past or current use of anticonvulsants

bDeath-related reasons leading to treatment discontinuations in the ITT population of TTFields therapy EF-19 registry, n (%), were due to: underlying disease, 88 (46); pneumonia respiratory failure, 1 (1); cardiopulmonary arrest, 1 (1); and unknown causes, 44 (23)

cOther reasons leading to treatment discontinuations in the ITT population of EF-19 TTFields therapy registry arm, n (%), were due to: PD, 14 (7); other medical reasons, 8 (4); patient decision, 14 (7); physician’s decision, 7 (4); MRI scan did not show tumor, 1 (1); and unknown reasons, 6 (3)

dPP population defined as patients who received ≥ 28 days of TTFields monotherapy (200 kHz) for ≥ 18 h/day on average in the first month of treatment and all PC-SOC patients

The disposition of patients treated with TTFields therapy in the EF-19 registry study is summarized in Table 1. All patients treated with PC-SOC (N = 117) received systemic therapy, either during or after the EF-11 study, and were included in the PC-SOC PP population [32]. Of these patients, 26 (22%) withdrew consent and were lost to safety follow-up, for which only survival data was collected. Safety data are presented for the remaining 91 (78%) patients in the PC-SOC control arm.

Efficacy outcomes

Primary efficacy outcome

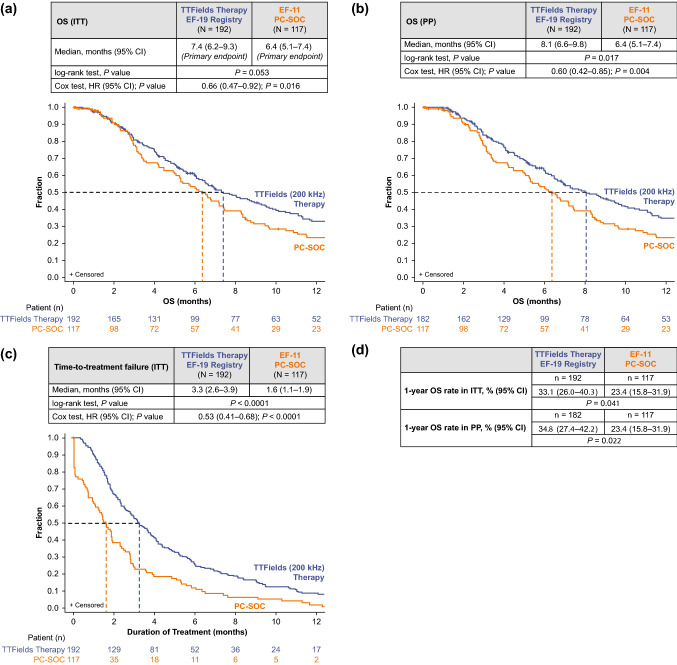

In the ITT population, OS (95% CI) was 7.4 months (range 6.2–9.3) with TTFields therapy vs 6.4 months (range 5.1–7.4) with PC-SOC (P = 0.053, log-rank test; Fig. 1A). The Cox proportional HR was 0.66 (95% CI 0.47–0.92; P = 0.016, Cox test; Fig. 1A). The primary endpoint was met (HR 95% CI upper limit was ≤ 1.375, pre-defined threshold). The statistically significant Cox test for HR of 0.66 (P = 0.016) indicated that TTFields therapy reduced risk of death by 34% vs PC-SOC.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve comparing TTFields (200 kHz) therapy from EF-19 registry and PC-SOC patients with rGBM for a OS in ITT populations (primary endpoint), b OS in PP populations, c time to treatment failure in ITT populations, and d 1-year OS rates in ITT and PP populations. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intent-to-treat; OS, overall survival; PC-SOC, physicians’ choice standard of care; PP, per protocol; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

Additional efficacy outcomes

In the PP population, OS (95% CI) was 8.1 months (range 6.6–9.8) with TTFields therapy vs 6.4 months (range 5.1–7.4) with PC-SOC (P = 0.017, log-rank test; Fig. 1B). The Cox proportional HR for OS (95% CI) was 0.60 (0.42–0.85), showing statistical significance (P = 0.004, Cox test; Fig. 1B).

Median (95% CI) time to treatment failure in the ITT population was 3.3 months (range 2.6–3.9) with TTFields therapy and 1.6 months (range 1.1–1.9) with PC-SOC (P < 0.0001, log-rank test; Fig. 1C). The Cox proportional HR (95% CI) for time to treatment failure was 0.53 (0.41–0.68) for TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC (Cox test P < 0.0001; Fig. 1C).

Moreover, OS rate (95% CI) at 1 year in the ITT population was 33% (26–40) with TTFields therapy and 23% (16–32) with PC-SOC (P = 0.041). The OS rate (95% CI) in the PP population was 35% (27–42) with TTFields therapy and 23% (16–32) with PC-SOC (P = 0.022, log-rank test; Fig. 1D). Improved OS rate at 1 year was ~ 1.5 times greater in both ITT and PP populations with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC.

Subgroup analyses

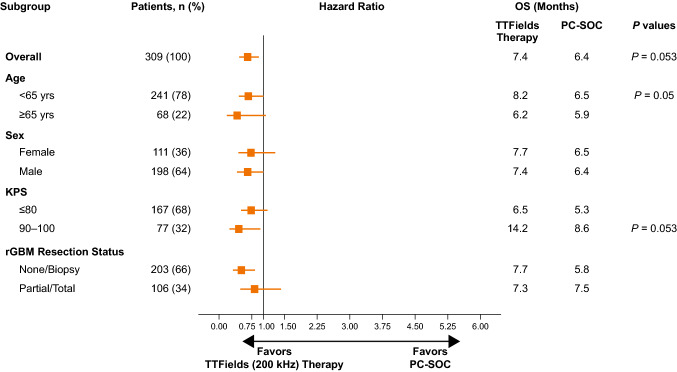

In additional analyses, TTFields monotherapy was associated with a statistically significant increase in OS overall, and within certain patient subgroups in the ITT population (Fig. 2; Cox proportional hazards, P < 0.05 for the treatment effect within each subgroup). Clinical benefit of TTFields therapy on OS was observed regardless of KPS, age, sex, and rGBM resection status. Similar findings were obtained when patients were stratified by rGBM resection status—none/biopsy/partial resection vs those with gross total resection (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Cox hazard ratios of OS by prognostic factor subgroups in EF-19 registry of TTFields therapy (N = 192) and PC-SOC (N = 117) in ITT population for patients with rGBM. Symbols represent Cox HRs in each subgroup of patients treated with TTFields therapy in EF-19 registry compared to PC-SOC arm (EF-11 clinical study control group), while adjusting for other prognostic factors. Whiskers represent the 95% CIs of the HR. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status score; OS, median overall survival; PC-SOC, physicians’ choice standard of care; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

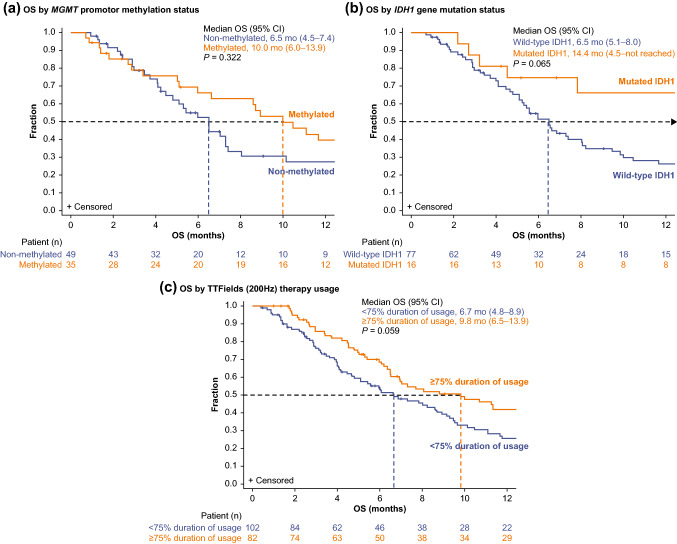

In the TTFields therapy arm, patients whose tumors were MGMT promoter methylation status positive had a numerically extended OS (95% CI) of 10 months (6.0–13.9) vs 6.5 months (4.5–7.4) in patients with tumor-negative status; HR (95% CI) was 0.77 (0.46–1.30), (P = 0.322, log-rank test; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of EF-19 registry of patients with rGBM treated with TTFields (200 kHz) therapy in the ITT population by subgroup analyses: a MGMT promotor methylation status (n = 84), b IDH1 gene mutation status (n = 93), and c duration of TTFields treatment usage (n = 184). CI, confidence interval; IDH1, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1; MGMT, O6-Methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase; OS, overall survival; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

Patients with IDH1 gene mutation in the ITT population demonstrated a trend toward longer OS (95% CI) of 14.4 months (4.5–not reached) vs 6.5 months (5.1–8.0) in patients with wild-type IDH1 gene status; HR (95% CI) of 0.52 (0.25–1.05; P = 0.065 Fig. 3B). These tumor biomarker subgroup assessments (IDH1 and MGMT) were not performed in the EF-11 study (non-comparable).

In the TTFields arm, patients who were treated for ≥ 18 h/day (≥ 75% daily usage; monthly average in the first 6 months of treatment) in the ITT population had a longer OS (95% CI) of 9.8 months (6.5–13.9) vs 6.7 months (4.8–8.9) for < 18 h/day usage (< 75% daily usage, monthly average in the first 6 months of treatment); HR (95% CI) of 0.72 (0.50–1.01), P = 0.059, log-rank test (Fig. 3C). Moreover, treatment with TTFields therapy for ≥ 18 h/day usage vs PC-SOC was positively correlated with higher survival rates, respectively, at 6 (69% vs 52%; P = 0.011), 12 (42% vs 23%; P = 0.005), 15 (34% vs 22%; P = 0.049), and 18 (27% vs 18%; P = 0.091) months.

Adverse events

Safety data for all 192 registry patients with a database cut-off date of December 31, 2018 were compared descriptively to the 91 PC-SOC patients. The number of patients with any reported AE ≥ 1 was lower with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC (67% vs 95%, respectively) in the safety population (N = 283) (Table 2). Overall, PC-SOC treatment demonstrated higher AE incidence rates (≥ 5% incidence in any arm) compared to TTFields monotherapy across 12 of 15 classifications by MedDRA body system organ class (Table 2). For the 12 AE classes with greater AE incidence with PC-SOC, the most commonly reported AE by body system class in the PC-SOC arm was nervous system disorders (36%), followed by gastrointestinal disorders (30%) and blood and lymphatic system disorders (19%). In contrast, AE incidence rates were greater in the TTFields monotherapy vs PC-SOC group for 3 AE classifications, which were: skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (36%); general disorders and administration-site conditions (23%); and injury, poisoning, and procedural complications category (11%). There were no skin AEs in the EF-19 registry that resulted in TTFields therapy discontinuation. Reported skin AEs were deemed as non-serious, consistent with results from the previously reported EF-11 study.

Table 2.

Number of patients with adverse events by body system (≥ 5% incidence in any arm)

| MedDRA version 22.1 Body system, n (%) |

TTFields therapy EF-19 Registry (N = 192) |

PC-SOC EF-11 (N = 91) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with ≥ 1 any AE | 128 (67) | 86 (95) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 (0) | 17 (19) |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 (1) | 6 (7) |

| Eye disorders | 0 (0) | 5 (5) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 8 (4) | 27 (30) |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | 45 (23) | 14 (15) |

| Infection and infestations | 6 (3) | 11 (12) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 22 (11) | 1 (1) |

| Investigations | 0 (0) | 5 (5) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1 (1) | 12 (13) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 8 (4) | 8 (9) |

| Nervous system disorders | 51 (27) | 33 (36) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 7 (4) | 7 (8) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 2 (1) | 10 (11) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 70 (36) | 9 (10) |

| Vascular disorders | 2 (1) | 6 (7) |

Percent values have been rounded to nearest integer

AEs adverse events; MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; PC-SOC physicians’ choice standard of care; TTFields Tumor Treating Fields

Discussion

This was a post-marketing registry study conducted in the real-world setting in patients with rGBM. This study was conducted to provide further evidence to support the efficacy and tolerability of TTFields therapy in rGBM following the phase III EF-11 clinical study, which underpinned approval in the EU, US, Japan, and China [16, 25–28]. Data from this study confirmed that TTFields monotherapy (200 kHz) was noninferior to PC-SOC in OS compared with EF-11 study data [32]. OS in TTFields monotherapy patients was comparable to PC-SOC in the ITT population (primary endpoint), with a more favorable safety profile. After a minimum follow-up of 12 months, OS was 7.4 vs 6.4 months for the TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC arms, respectively (HR [95% CI], 0.66 [0.47–0.92]; P = 0.053; Cox test P = 0.016), indicating that TTFields therapy may reduce the risk of death by 34% vs PC-SOC. Interestingly, time to treatment failure was improved with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC (3.3 vs 1.6 months, respectively; log-rank test, P < 0.0001), and OS was extended for the PP population (8.1 vs 6.4 months) in the TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC arms, respectively (key additional endpoint; HR [95% CI], 0.60 [0.42–0.85]; P = 0.017; Cox test P = 0.004).

TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC, respectively, showed increases in 1-year OS rates of 43% for the ITT (33% vs 23%) and 52% for the PP (35% vs 23%) populations, suggesting improved long-term survival benefit with TTFields therapy. Patients treated with TTFields therapy who met the usage goal of ≥ 18 h/day (≥ 75% daily usage) had higher OS rates than PC-SOC-treated patients at 12 (42% vs 23%) and 18 (27% vs 18%) months. A similar suggestion of improved survival with usage over time of ≥ 18 h per day has been observed for patients with ndGBM treated with TTFields therapy (EF-14 study) [42].

The findings of the present study support the findings of a noninferiority analysis of the EF-11 overall survival data, which indicated that TTFields therapy may be at least equivalent to active chemotherapy [32]. Interestingly, the proportion of patients who had at least one cycle of treatment was higher in this real-world population compared with patients receiving TTFields monotherapy in EF-11 (95% vs 78%). This registry study was initiated following the approval of TTFields therapy for GBM, by the FDA, which may have increased patient/physician acceptance and level of usage to the treatment, contributing to the increased treatment exposure.

A weakness of this study is that the comparator group is a historical control (as is typical of a registry study), although it is used to compare relative to a prospectively collected data set. Furthermore, real-world studies inherently lack the robustness of standardized randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and may be subject to a level of selection and interpretation bias not associated with more tightly controlled RCTs. As such, baseline demographic variations between treatment groups, such as the unavailability of KPS score for approximately one-third of study group patients, could lend potential bias to the results. Nevertheless, real-world evidence and RCT data are mutually complementary, and the real-world data presented here are in line with and lend further support to the data published in the EF-11 study.

Although differences in baseline prognostic factors may impact the results of the comparison of outcomes, we note there was a trend of observed benefit with use of TTFields therapy for rGBM treatment across the evaluated subgroups in the ITT population. Patient characteristics that were associated with maximal benefit with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC, respectively, were < 65 years of age (8.2 vs 6.5 months; log-rank test P = 0.05 and KPS of 90–100 (14.2 vs 8.6 months; log-rank test P = 0.053).

There was clinical benefit with TTFields therapy vs PC-SOC, respectively, in patients with MGMT promotor methylation (10.0 vs 6.5 months) and with IDH1 gene mutation (14.4 vs 6.5 months) statuses. The benefit observed in patients with MGMT non-methylated promotor status and extended benefit in methylated promoter status [43] suggests broad utility of TTFields therapy in these subgroups, as monotherapy and concomitant with TMZ [44], especially in the non-methylated promoter subgroup with limited treatment options [45]. Previous data have shown benefit with TTFields therapy in patients with IDH1 wild-type ndGBM tumors [31]. The data obtained from the present study lends further support to the previous findings in IDH1 wild-type tumors, with probable extended benefit in IDH1 mutation-positive patients.

As expected, TTFields therapy was well tolerated with a favorable safety profile compared with PC-SOC. The most common treatment-related AEs were manageable and resoluble local skin AEs at array site of contact rather than systemic, less-tolerable chemotherapy-related AEs. Beneath-array localized skin AEs associated with TTFields therapy may include contact dermatitis, hyperhidrosis, pruritus, skin erosion, or ulceration [41], and can typically be managed by practical approaches including optimal shaving and shifting the array position (~ 2 cm), or by the use of early pharmaceutical interventions [41].

Patients receiving PC-SOC experienced a higher rate of chemotherapy-related AEs (e.g., nervous system, gastrointestinal, hematological, metabolic, and infectious) vs those receiving TTFields therapy. The reported incidence of neurological symptoms across both treatment arms was expected, due to known-reported underlying GBM disease burden, including headaches, seizures, and cognitive changes [41, 46]. Importantly, TTFields therapy did not increase the incidence of such neurological AEs.

Conclusions

In this EF-19 prospective, post-marketing registry study of adult patient population with rGBM, TTFields monotherapy (200 kHz) demonstrated efficacy and safety, providing support to the phase III EF-11 study findings. Patients who received TTFields monotherapy showed comparable OS in the ITT population, improved OS in the PP population, and a more tolerable/favorable safety profile vs PC-SOC in this real-world setting. No new safety signals or increases in systemic side effects were observed. Therefore, these data provide additional supportive evidence of the efficacy and safety of TTFields therapy as an appropriate therapy for rGBM patient population. Furthermore, as in other previously reported studies demonstrating the clinical effectiveness of TTFields therapy, continuous use of TTFields therapy for ≥ 18 h per day (over a 4-week average) was associated with better survival outcomes vs lower usage time.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Writing and editorial support under the direction of the authors was provided by Huda Abdullah, PhD, Global Publications, Novocure Inc., USA, Emma Butterworth, PhD, Excerpta Medica Inc., and Melissa Purves, PhD, CMPPTM, Prime, Knutsford, UK. Writing and editorial support provided by Excerpta Medica Inc. and Prime was funded by Novocure Inc. All costs related to publication were funded by Novocure Inc. Responsibility for all opinions, conclusions, and data interpretation lies with the authors.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of this primary manuscript, including data collection, reviewed and edited the drafts, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Novocure® Inc.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available 3 years after date of publication.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this was a post-marketing registry study, no ethical approval was required. All patients enrolled in the TTFields therapy registry and who met eligibility criteria had previously provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment, inclusive of use of protected health information.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Jay-Jiguang Zhu has been supported by the following for-profit companies for clinical trials and contracted research with payments made to his institution: Denovo Biopharma, Novocure, Inc., Five Prime Therapeutics, Inc., Boston Biomedical of Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd.

Samuel A Goldlust has received honoraria for lectures, consultation or advisory board participation from the following: Daiichi Sankyo, Cellevolve, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Oncology, Physicians' Education Resource, Cornerstone Specialty Network, Novocure, Inc., Wex Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Tocagen, Cortice Biosciences, and Boston Biomedical. SAG owns stock in COTA and received support for travel, accommodations, and expenses from the following: Wex Pharmaceuticals, Tocagen, Novocure, Inc., Boston Biomedical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cortice Biosciences, Caris Life Sciences, Kyowa Kirin International. The following have supported clinical trials and contracted research conducted by SAG with payments made to his institution: AbbVie, Acerta Pharma, Amgen, Boston Biomedical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cantex Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Celldex, Cellularity, CNS Healthcare, Cortice Biosciences, Diffusion Pharmaceuticals, Immunocellular Therapeutics, Imvax, Karyopharm, Kazia, Merck, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Novocure, Novogen, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Oncology, Tocagen, Regeneron and Wex Pharmaceuticals.

Lawrence Kleinberg has received honoraria for lectures, consultation, or advisory board from the following for-profit companies; Accuray and Novocure, Inc. The following for-profit companies have supported clinical trials and contracted research conducted by Lawrence Kleinberg with payments made to his institution: Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Accuray, Novartis, and Novocure, Inc.

Jérôme Honnorat has received honoraria for lectures and advisory board participation from the following for-profit companies: Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, and Novocure, Inc.

Nancy Ann Oberheim Bush has received honoraria for lectures, consultation or advisory board participation from the following for-profit company: GLC. The following for-profit companies have supported clinical trials and contracted research conducted by NAOB with payments made to her institution: Merck and Ziopharm.

Zvi Ram serves as a consultant to Novocure, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rushing EJ. WHO classification of tumors of the nervous system preview of the upcoming 5th edition. Mag Eur Med Oncol. 2021;14(2):188–191. doi: 10.1007/s12254-021-00680-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taphoorn MJB, Dirven L, Kanner AA, et al. Influence of treatment with tumor-treating fields on health-related quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(4):495–504. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Gilbert MR, Chakravarti A. Chemoradiotherapy in malignant glioma: standard of care and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(26):4127–4136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Gorlia T, et al. Cilengitide combined with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CENTRIC EORTC 26071–22072 study): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):709–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avecillas-Chasin JM, Atik A, Mohammadi AM, Barnett GH. Laser thermal therapy in the management of high-grade gliomas. Int J Hyperth. 2020;37(2):44–52. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2020.1767807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallabanda K, Yanez L, Sallabanda M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of recurrent high-grade gliomas: long-term follow-up. Cureus. 2019;11(12):e6527. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, et al. Glioblastoma in adults: a Society for neuro-oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(8):1073–1113. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry JR, Rizek P, Cashman R, Morrison M, Morrison T. Temozolomide rechallenge in recurrent malignant glioma by using a continuous temozolomide schedule: the "rescue" approach. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2152–2157. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wick W, Puduvalli VK, Chamberlain MC, et al. Phase III study of enzastaurin compared with lomustine in the treatment of recurrent intracranial glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1168–1174. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.23.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reithmeier T, Graf E, Piroth T, et al. BCNU for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: efficacy, toxicity and prognostic factors. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954–1963. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birzu C, French P, Caccese M, et al. Recurrent glioblastoma: from molecular landscape to new treatment perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2020;13(1):47. doi: 10.3390/cancers13010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novocure. Optune®: instructions for use. 2019. https://www.optune.com/Content/pdfs/Optune_IFU_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- 17.Novocure Optune®: instructions for use for unrescetable malignant pleural mesothelioma. 2021. https://www.optunelua.com/pdfs/Optune-Lua-MPM-IFU.pdf?uh=18f20e383178129b5d6cd118075549592bae498860854e0293f947072990624c&administrationurl=https%3A%2F%2Foptunelua-admin.novocure.intouch-cit.com%2F. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- 18.Mun EJ, Babiker HM, Weinberg U, Kirson ED, Von Hoff DD. Tumor-treating fields: a fourth modality in cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(2):266–275. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karanam NK, Story MD. An overview of potential novel mechanisms of action underlying Tumor Treating Fields-induced cancer cell death and their clinical implications. Int J Radiat Biol. 2021;97(8):1044–1054. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2020.1837984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper GM. The development and causes of cancer. In: Cooper GM, editor. The cell: a molecular approach. 2. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baba AI, Câtoi C. Tumor cell morphology. In: Baba AI, editor. Comparative oncology. Bucharest: The Publishing House of the Romanian Academy; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trainito CI, Sweeney DC, Cemazar J, et al. Characterization of sequentially-staged cancer cells using electrorotation. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haemmerich D, Schutt DJ, Wright AW, Webster JG, Mahvi DM. Electrical conductivity measurement of excised human metastatic liver tumours before and after thermal ablation. Physiol Meas. 2009;30(5):459–466. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/5/003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad MA, Natour ZA, Mustafa F, Rizvi TA. Electrical characterization of normal and cancer cells. IEEE Access. 2018;6:25979–25986. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2830883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novocure. Novocure announces Japanese approval of Optune (the NovoTTF-100A System) for treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. 2015. https://www.novocure.com/novocure-announces-japanese-approval-of-optune-the-novottf-100a-system-for-treatment-of-recurrent-glioblastoma/. Accessed 22 Jan 2020.

- 26.Novocure. Novocure’s Optune® (NovoTTF-100A) approved in Japan for the treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma. 2016. https://www.novocure.com/novocures-optune-novottf-100a-approved-in-japan-for-the-treatment-of-newly-diagnosed-glioblastoma/. Accessed 22 Jan 2022

- 27.Novocure. Optune®: instructions for use (EU). 2020. https://www.optune.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Optune_User_Manual_ver2.0.pdf Accessed 1 Feb 2022.

- 28.ZaiLab. China NMPA Approves Optune® for the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed and Recurrent Glioblastoma. 2020. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/05/13/2032766/0/en/China-NMPA-Approves-Optune-for-the-Treatment-of-Newly-Diagnosed-and-Recurrent-Glioblastoma.html. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

- 29.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network®. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Central Nervous System Cancers. Version 1.2021. 2021. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1425. Accessed 18 Oct 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Novocure. NCCN guidelines recommend Optune in combination with temozolomide as a category 1 treatment for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. 2018. https://www.novocure.com/nccn-guidelines-recommend-novocures-gbm-therapy-in-combination-with-temozolomide-as-a-category-1-treatment-for-newly-diagnosed-glioblastoma/. Accessed 12 July 2022.

- 31.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2306–2316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, et al. NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2192–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ceresoli GL, Aerts JG, Dziadziuszko R, et al. Tumour treating fields in combination with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin as first-line treatment for unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (STELLAR): a multicentre, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):1702–1709. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pless M, Droege C, von Moos R, Salzberg M, Betticher D. A phase I/II trial of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy in combination with pemetrexed for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(3):445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benavides M, Guillen C, Rivera F, et al. PANOVA: A phase II study of TTFields (150 kHz) concomitant with standard chemotherapy for front-line therapy of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma—updated efficacy results. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):e15790–e15790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e15790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vergote I, von Moos R, Manso L, et al. Tumor Treating Fields in combination with paclitaxel in recurrent ovarian carcinoma: results of the INNOVATE pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(3):471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivera F, Benavides M, Gallego J, et al. Tumor Treating Fields in combination with gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer: results of the PANOVA phase 2 study. Pancreatology. 2019;19(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gkika E, Touchefeu Y, Mercade TM, et al. HEPANOVA: final efficacy and safety results from a phase 2 study of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields, 150 kHz) concomitant with sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Ann Oncol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.05.808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mrugala MM, Engelhard HH, Dinh Tran D, et al. Clinical practice experience with NovoTTF-100A™ system for glioblastoma: the Patient Registry Dataset (PRiDe) Semin Oncol. 2014;41(Suppl 6):S4–S13. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi W, Blumenthal DT, Oberheim Bush NA, et al. Global post-marketing safety surveillance of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) in patients with high-grade glioma in clinical practice. J Neurooncol. 2020;148(3):489–500. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03540-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Ballo MT, et al. Prevention and management of dermatologic adverse events associated with Tumor Treating Fields in patients with glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1045. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toms SA, Kim CY, Nicholas G, Ram Z. Increased compliance with tumor treating fields therapy is prognostic for improved survival in the treatment of glioblastoma: a subgroup analysis of the EF-14 phase III trial. J Neurooncol. 2019;141(2):467–473. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-03057-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Tumor treating fields (TTFields): A novel treatment modality added to standard chemo- and radiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma—first report of the full dataset of the EF14 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15):2000. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark PA, Gaal JT, Strebe JK, et al. The effects of tumor treating fields and temozolomide in MGMT expressing and non-expressing patient-derived glioblastoma cells. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;36:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah N, Schroeder B, Cobbs C. MGMT methylation in glioblastoma: tale of the tail. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(1):167–168. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.IJzerman-Korevaar M, Snijders TJ, de Graeff A, Teunissen S, de Vos FYF. Prevalence of symptoms in glioma patients throughout the disease trajectory: a systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2018;140(3):485–496. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-03015-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available 3 years after date of publication.

Not applicable.