Abstract

Despite the surge of interest in digital globalization, its social dimensions have received far less attention than deserved. The lack of conversation between the two prominent areas of IB research, digitalization, and corporate social responsibility, presents a valuable opportunity for extending the agenda Ioannou and Serafeim (J Int Bus Stud 43(9):834–864, 2012) pioneered a decade earlier. We briefly depict the organizational differences between multinational enterprises (MNEs) and multinational platforms (MNPs), followed by a closer look at how social responsibility of digital platforms might depart from our conventional understanding derived from MNEs. We then propose the notion of ecosystem social responsibility emphasizing social value co-creation before categorizing the main areas of social issues specific to MNPs. Based on these ideas, we derive several new insights into the social challenges faced by firms governing global platforms versus multidomestic platforms, respectively, as they serve international markets. Lastly, we discuss future research directions and, in particular, the implications for ecosystem sustainability.

Keywords: ecosystem, social responsibility, digital platform, international, society, sustainability

Résumé

Malgré le regain d'intérêt pour la globalisation numérique, ses dimensions sociales ont reçu beaucoup moins d'attention qu'elles ne le méritent. L'absence de conversation entre les deux principaux domaines de recherche en affaires internationales, à savoir la numérisation et la responsabilité sociale des entreprises, constitue une occasion précieuse d'étendre le programme que Ioannou et Serafeim (2012) ont lancé une décennie plus tôt. Nous décrivons brièvement les différences organisationnelles entre les entreprises multinationales (Multinational enterprises - MNEs) et les plates-formes multinationales (Multinational platforms - MNPs). Puis, nous examinons de plus près comment la responsabilité sociale des plates-formes numériques pourrait diverger de notre compréhension conventionnelle dérivée des MNEs. Nous proposons ensuite la notion de responsabilité sociale de l'écosystème en mettant l'accent sur la cocréation de valeur sociale, et ce avant de catégoriser les principaux domaines de problèmes sociaux propres aux MNPs. Sur la base de ces idées, nous élaborons plusieurs nouveaux renseignements sur les défis sociaux auxquels sont confrontées les entreprises qui régissent des plates-formes multidomestiques vs globales durant leurs exploitations des marchés internationaux. Enfin, nous discutons de futures directions de recherche et, en particulier, des implications pour la durabilité des écosystèmes.

Resumen

Pese al auge del interés por la globalización digital, sus dimensiones sociales han recibido mucha menos atención de la que merecen. La falta de conversación entre las dos áreas prominentes de la investigación de negocios internacionales, la digitalización y la responsabilidad social corporativa, presenta una valiosa oportunidad para ampliar la agenda que Ioannou y Serafeim (2012) iniciaron una década antes. Describimos brevemente las diferencias organizacionales entre las empresas multinacionales (EMN) y las plataformas multinacionales (MNPs por sus iniciales en inglés), seguidas de un análisis más detallado de cómo la responsabilidad social de las plataformas digitales podría apartarse de nuestra comprensión convencional derivada de las empresas multinacionales. A continuación, proponemos la noción de responsabilidad social del ecosistema, que enfatiza la co-creación de valor social, antes de clasificar las principales áreas de los asuntos sociales específicos de las plataformas multinacionales. Sobre la base de estas ideas, derivamos varios aportes nuevos sobre los retos sociales a los que se enfrentan las empresas que dominan las plataformas globales versus las plataformas multidomésticas, respectivamente, cuando sirven a los mercados internacionales. Por último, discutimos las direcciones futuras de la investigación y, en particular, las implicaciones para la sostenibilidad del ecosistema.

Resumo

Apesar do aumento do interesse pela globalização digital, suas dimensões sociais receberam muito menos atenção do que merecem. A falta de diálogo entre as duas proeminentes áreas de pesquisa em IB, digitalização e responsabilidade social corporativa, apresenta uma oportunidade valiosa para estender a agenda que Ioannou e Serafeim (2012) introduziram uma década antes. Descrevemos brevemente as diferenças organizacionais entre empresas multinacionais (MNEs) e plataformas multinacionais (MNPs), seguidas de um olhar mais atento sobre como a responsabilidade social de plataformas digitais pode se afastar do nosso entendimento convencional derivado de MNEs. Em seguida propomos a noção de responsabilidade social ecossistêmica enfatizando a cocriação de valor social antes de categorizar as principais áreas de questões sociais específicas de MNPs. Baseados nessas ideias, derivamos vários novos insights sobre os desafios sociais enfrentados pelas empresas que governam plataformas globais versus plataformas multidomésticas, respectivamente, ao atender mercados internacionais. Por fim, discutimos futuras direções de pesquisa e, particularmente, as implicações para a sustentabilidade ecossistêmica.

Abstract

尽管人们对数字全球化的兴趣激增, 其社会维度受到的关注却远远少于应得的关注。国际商务(IB)研究的数字化和企业社会责任这两个突出领域之间对话的缺乏为扩展Ioannou和Serafeim (2012) 十年前所开创的研究议程提供了宝贵的机会。我们简要描述了跨国企业 (MNE) 和跨国平台 (MNP) 之间的组织差异, 然后仔细研究了数字平台的社会责任可能会如何偏离我们对MNE的传统理解。我们然后提出了生态系统社会责任的概念, 强调社会价值共同创造, 然后对 MNP 特有的社会问题的主要领域进行了分类。基于这些想法, 我们提出了一些关于管理全球平台对比多国内平台的公司在服务国际市场时所面临的社会挑战的新见解。最后, 我们讨论了未来研究方向, 特别是对生态系统可持续性的启示。

Introduction

“It is clear that Facebook prioritizes profit over the well-being of our children and all users.”

— Sen. Blackburn, Senate Commerce Committee

“(Facebook have) not rolled out those integrity and security systems to most of the languages in the world. And that's what is causing things like ethnic violence in Ethiopia.”

— Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen

International business (IB) scholarship has always played to its strength by explicating modern phenomena in the global economy, of which Ioannou and Serafeim (2012) is a prominent example. Their study depicts a comprehensive picture of home-country institutional impacts on firm-level social performance, ushering in a fruitful research agenda regarding corporate social responsibility (CSR) in IB. Much has been said since then about how firms, and especially multinational enterprises (MNEs), adopt various CSR practices in response to host-country stakeholder pressures (Marano, Tashman, & Kostova, 2017; Zhou & Wang, 2020), and, perhaps more controversially, how firms transfer irresponsible activities to foreign markets because of stakeholder constraints in the home country (Berry, Kaul, & Lee, 2021; Surroca, Tribó, & Zahra, 2013). Meanwhile, empirical studies widely inherit the practice of using environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics to measure firms’ social performance, either at home or abroad (Albino-Pimentel, Oetzel, Oh, & Poggioli, 2021; Mohr, Schumacher, & Kiefner, 2022).

One decade on, the changing global economy has arrived at a new, digital, era, where firms and economic agents coalesce into meta-organizations, as cultivated by digital transformation (Li, Chen, Yi, Mao, & Liao, 2019). That has led to increased complexity of societal impacts and ESG performance (George & Schillebeeckx, 2022), which nonetheless offers IB scholars promising opportunities to extend the research agenda that Ioannou and Serafeim (2012) advanced. To demonstrate this opportunity, we focus on multinational platforms (MNPs) which have been regarded as a prevailing form of such meta-organizations (Chen, Li, Wei, & Yang, 2022b). While recent studies have shed much-needed light on unique ways of cross-border operations characterizing the digital age, scholars like Verbeke and Hutzschenreuter (2021) caution that narratives around digital globalization have been predominantly expressed in positive terms, while overlooking the societal challenges MNPs pose, an issue of increasing concern to the IB community seeking practical relevance (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017).

We find this gap in the literature concerning, as MNPs often make the news headlines for rampant social irresponsibility. In the US Senate hearing in late 2021, whistleblower Frances Haugen, a former product manager on Facebook's civic misinformation team, accuses the firm of harming teen users’ mental health in pursuit of advertising revenue, and of promoting hate speech which leads to real-world ethnic violence in countries like Ethiopia and Myanmar.1 Other social platforms, like Twitter and YouTube, were also slammed for spreading misinformation during the 2016 US presidential campaign and the EU referendum in the UK (Reisach, 2021). Meanwhile, Google was fined €2.4bn by the EU for antitrust accusations,2 and Facebook was sued by the Federal Trade Commission and 46 states for squashing competition.3 This is not to mention user privacy violation which rendered Facebook a $5bn penalty by the US regulator.4 On the other hand, some MNPs creatively combine their distinct organizational form with ecosystem partners’ resources in responding to and addressing pressing issues that concern the wider society. For instance, Airbnb established a dedicated charitable site, Airbnb.org, to provide people with emergency housing in times of crisis. A recent initiative is offering free temporary housing around the world to 100,000 refugees fleeing Ukraine; anyone (not only current Airbnb hosts) willing to participate can welcome refugees to their residence while Airbnb covers the costs.5 Similar arrangements were organized to house healthcare workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating that MNPs can be a crucial positive force for addressing societal challenges.

Prior IB research suggests that CSR is more important and challenging for some MNEs than others. For instance, economic visibility, i.e., operations generating high levels of scale, customers, and employment, renders firms highly exposed to host country stakeholders’ institutional demands (Rosenzweig & Singh, 1991; Young & Makhija, 2014). Operations that entail substantial risks or novel business models also raise the need for local legitimacy (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006). While firms with global operations are embedded in meta-institutional fields and respond to global institutional pressures (Tashman, Marano, & Kostova, 2019), international diversification may increase coordination cost leading to greater incidence of social irresponsibility in host countries (Strike, Gao, & Bansal, 2006). All of these suggest that social responsibility should be of immediate relevance to MNPs, which demonstrate significant visibility because of their sheer scale and impact on the local economy, are globally dispersed in operations, and pose profound risks regarding power concentration and data privacy (Cutolo & Kenney, 2021). More importantly, social responsibility of platforms reaches well beyond the platform firm’s boundaries, and relies on their private governance to establish social norms conditioning all ecosystem participants (Chen et al., 2022b). As the earlier examples demonstrate, the failing of private governance can not only generate negative externalities in host countries but also jeopardize the sustainability of an otherwise successful platform business. However, despite the inherent link between MNPs and CSR, CSR research to date rarely extends to MNPs, and the literature on platform ecosystems has also not systematically accounted for CSR. The new JIBS editorial policy highlights these two research areas as fundamentally important for IB going forward, suggesting an imperative to explicate their linkage.

In extending Ioannou and Serafeim (2012), we seek to bridge this gap, based on the premises that MNPs’ global influence is creating a fundamental change in the scale and scope of social expectations that are unprecedented for previous forms of value chain organizations, which presents a new context of institutional fields for extending global CSR and sustainability research. Our study first outlines the differences between MNEs and MNPs, and explicates their implications for CSR research. On that basis, we propose the notion of ecosystem social responsibility (ESR) which arises from opportunities and expectations of social value co-creation, and we use an integrative framework to categorize the main areas of social responsibility that are specific to MNPs. We then derive a set of new insights to help understand the social challenges faced by two archetypal types of MNPs – global platforms and multidomestic platforms – as they serve markets around the world. The proposed insights focus on the perspective of platform firms whose governance roles have proved to exert significant societal impacts (Han, Wang, Ahsen, & Wattal, 2022). Our conceptual development culminates with new directions for future IB research, inviting deeper reflection on ecosystem sustainability, an area deserving greater attention. In contributing to the literature, this paper enriches the growing research on CSR in cross-border relationships (Sun, Doh, Rajwani, & Siegel, 2021), and, at the same time, answers the call for a more balanced perspective on digital globalization that duly recognizes institutional challenges and social implications (Luo, 2022; Verbeke & Hutzschenreuter, 2021). Given that a firm’s ESG performance is linked to its competitive advantage and financial performance (Wang, Choi, & Li, 2008), we also submit that, at the ecosystem level, ESR is ultimately a missing piece of the jigsaw in understanding ecosystem-specific advantages and sustainable development of the digital economy.

Digital platforms and social responsibility

MNPs and Ecosystem Participants

Scholars often frame platforms as two-sided or multisided markets, in which transactions and interactions between complementors and users take place (McIntyre & Srinivasan, 2017). Complementors offer complementary products utilizing the platform interface and other platform resources, while platform users consume such products (rather than the platform interface per se). Digital platforms refer to a specific type of platform that serves as a standardized digital interface, and utilizes digital technologies to facilitate interactions between different parties (Chen, Tong, et al., 2022). The demand interdependence within or between these groups of actors generates “network externalities”, in that their utility depends on the amount, composition, and behaviors of other actors within the ecosystem (Rietveld & Schilling, 2021).

Since multilateral interdependence constitutes a defining feature distinguishing platform ecosystems from hierarchical organizations, or arm’s length dealings, researchers have paid growing attention to the governance rules and design features by which the platform owner directs, coordinates, and controls interactions within the ecosystem it establishes (Chen, Yi, et al., 2022). For example, digital platforms like Yelp use filtering algorithms to detect and remove fake reviews that complementors leave for themselves (and rival merchants), in attempts to contain fraudulent behaviors and protect users’ interests (Luca & Zervas, 2016). This body of research has led to an emergent perspective that conceptualizes platform ecosystems as meta-organizations, where the governance of a vast amount of loosely-coupled partners shapes value creation and ecosystem competitiveness (Chen, Tong, et al., 2022; Kretschmer, Leiponen, Schilling, & Vasudeva, 2022). In developing the notion of ecosystem-specific advantages, IB scholars specifically incorporate “governance” as one of the core components (Li et al., 2019), and frame the relationship between platform owners and complementors as a “hybrid” form that is underpinned by voluntary exchange of property rights (Chen et al., 2022b). This conceptual perspective points to the unique organizational structures of MNPs that depart from the integration of foreign subsidiaries or contractual relationships with suppliers commonly associated with MNEs (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019). Table 1 provides a summary. However, despite the extensive discussion of this new organizational form, much focus has been on economic value and performance while its social dimensions remain largely unattended.

Table 1.

Organizational differences between MNEs and MNPs

| Organizational features | Multinational enterprises (MNEs) | Multinational platforms (MNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational structure | Integration of geographically dispersed units | Loose coupling with global complementors |

| Ecosystem stakeholders | Contractually bound supply chain partners | Complementors and users |

| Structural feature of the ecosystem |

Closed membership Linear, pipeline-like relationship |

Open membership Interdependence between complementors and users |

| Main interface with the host environment | Host-country subsidiaries | Host/third-country complementors |

| Governance of the interface | Fiat | Coordination |

Differences in Social Responsibility

Prior studies of CSR are predicated on the organizational structures of traditional MNEs. There is consensus that the hierarchical relationship between foreign subsidiaries and the headquarters leads to liabilities of foreignness and reputation spillover that subsidiaries will face in a host country (Zhou & Wang, 2020). These challenges prompt subsidiaries to conduct CSR which may be converted to intangible assets enabling internationalizing firms to mitigate home-country-related illegitimacy (Marano et al., 2017). CSR can achieve so by improving foreign firms’ institutional embeddedness and conferring social licenses for operating in a foreign environment (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006; Hornstein & Zhao, 2018; Mithani, 2017). Moving beyond the legitimacy perspective, other scholars subscribe to a strategic view, arguing that leadership in CSR practices can create firm-specific advantages in foreign markets in a similar way as other types of differentiation (Kolk & Pinkse, 2008). These conclusions are formulated based on MNEs’ operations; whether they are readily applicable to platform ecosystems is unclear given the organizational differences.

There are some notable implications of different organizational structures for CSR. For some MNPs, such as Amazon, the platform firm may establish local subsidiaries which undertake foreign operations in a similar way as traditional MNEs. Yet, for other MNPs like TikTok, it is the complementors or autonomous content creators, rather than foreign subsidiaries themselves, who occupy the interface with the institutional environments in which it operates (Chen, Li, Shaheer, & Stallkamp, 2022a). The conformity to local expectations may be attained by host-country complementors, who supposedly possess sufficient local institutional knowledge and embeddedness (Brouthers, Chen, Li, & Shaheer, 2022). Moreover, research on CSR reporting has employed a value-chain perspective, and investigates the MNE’s responsibility for upstream stakeholders (e.g., suppliers) and downstream stakeholders (e.g., customers) (Sun et al., 2021). By contrast, platforms operate as an intermediary for other actors to interact; the value-creating exchanges mainly occur between complementors and users. That might result in a reduced ability of the platform owner to monitor actors’ behaviors, such as careless driving by Uber drivers, and a heightened risk of misaligned norms and expectations between complementors and users, and between the platform owner and other local stakeholders (e.g., government regulators).

Hennart (2019) views this tension through the lens of franchising, in that the platform owner enlists the initiative of complementors using franchising-like contracts which are nonetheless ineffective in controlling excessive free-riding on quality. This view highlights an important contrast with traditional MNEs. Received wisdom suggests that foreign subsidiaries inherit the illegitimacy of the MNE, and often conduct CSR to counter that (Zhou & Wang, 2020). In contrast, stakeholders (e.g., Uber riders and taxi companies) may attribute any illegitimate actions observed on the MNP to the platform owner, thereby demanding additional investments, or, more radically, changes in the business model that will better serve societal goals (Ricart, Snihur, Carrasco-Farré, & Berrone, 2020). This is despite the common perception that the relationship between platform owners and complementors is a loosely-coupled one (Nambisan & Luo, 2021), and, in a way, echoes global value chains (GVCs) where stakeholders often hold the lead firm accountable. What distinguishes MNPs is the interdependence between ecosystem participants (e.g., between sellers and buyers) from which social illegitimacy arises. Unlike a GVC lead firm, it is not adequate for the platform owner to specify and enforce complementors’ ethical standards in their dyadic relationship. To avoid damage to its reputation, the platform owner (similar to a franchiser) must deploy numerous governance instruments, or so-called private governance, to control and incentivize the conduct of the complementors, especially how they interact with users (Chen, Tong, et al., 2022). How effective those governance instruments are to induce responsible behaviors beyond the legal requirement will play a substantial role in shaping a platform’s social performance ,and the collective benefits to all the ecosystem participants. Table 2 outlines common areas of research in the CSR literature and how MNPs differ from MNEs in these aspects.

Table 2.

How MNEs versus MNPs differ on common issues of social responsibility

| Common areas of CSR research | Multinational enterprises (MNEs) | Multinational platforms (MNPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of illegitimacy |

Home-country identity Lack of institutional embeddedness |

Disruptive business models Frictions between complementors and users |

| Home-country impact | Global arbitrage and outward transfer of irresponsible operations | Data storage and security concerns |

| Host-country impact | Donate to gain social licenses | New regulation imposed |

| Typical CSR behaviors |

CSR disclosure Philanthropy |

Socially responsible treatment of complementors and users, and elicit social responsibility of those actors |

| Role of the lead firm | Vouch for conformity in global supply chain | Establish global norm within its ecosystem |

Ecosystem Social Responsibility

While it is clear that platform ecosystems offer a new context for extending CSR research, what exactly social responsibility entails in a platform ecosystem remains elusive. We argue that, first and foremost, each ecosystem participant has its own social responsibility which is embedded in the respective value-creating activities, and revolves mainly around environmental and social dimensions. Seller-producers face similar issues of CSR reporting and supply chain auditing, as do other manufacturing firms. Users on information platforms such as Twitter, while mainly consuming information, may be responsible for creating dubious content and spreading “fake news”, eventually hurting social welfare in the wider society. However, when considering social responsibility at the platform ecosystem level, we submit that it is not a linear aggregation of ecosystem participants’ individual social (or environmental) actions; it may be greater than or less than the constituents’ social performance combined, as the platform owner wields governance instruments to enhance net social benefits at the collective level. This is where the governance dimension of ESG is prominently manifest.

Take complementors as an example. While submitting to the platform owner’s control and coordinative power because of expected economic gains, complementors are entitled to demand its fair treatment in worker rights protection and value distribution. On the other hand, complementors that “game” the platform rules and take opportunistic actions may cause significant externalities, and thus are confronted with institutional pressures from users; such value destruction may also jeopardize the reputation of the platform and harm its owner firm. The challenge lies in the interdependence structure (Adner, 2017), as changes in platform designs that are meant to promote complementors’ social performance may invite opportunistic behaviors, and eventually spillover to users and impair their interests. Similarly, platform owners’ policies that are socially desirable for users may render complementors unfairly treated. For instance, in protecting privacy, Apple’s iOS 14 prohibits third-party apps from collecting user data without users’ opt-in. Given that third-party apps rely widely on personalized advertising for revenue generation, this change of policy can significantly damage their financial performance, unjustly put Apple’s own apps at an advantage, and ultimately restrict consumer choice (Sokol & Zhu, 2021). These observations signal a unique source of ecosystem social irresponsibility: social frictions between ecosystem participants. Extant literature refers to friction as tension and discord in the encounter that arises from divergent interests (Shenkar, Luo, & Yeheskel, 2008). Because of social frictions and the externalities on internal and external stakeholders, the social performance of a platform ecosystem may be less than the linear addition of ecosystem participants’ individual performance. Conversely, as the example of Airbnb shows, MNPs also demonstrate unique advantages in mobilizing resources owned by complementors around the world. Co-specialized resources and capabilities of different ecosystem partners, if leveraged concertedly for social causes, can result in high levels of social synergies and positive externalities that contribute to ecosystem social responsibility, such that the social performance of a platform ecosystem may be greater than the aggregation of the constituents’ performance. The burden is on the platform owner to enhance net social benefits associated with an ecosystem, by reducing negative externalities and increasing positive externalities.

Therefore, we propose the idea of ecosystem social responsibility, which refers to the collective practices and policies undertaken by ecosystem participants in contributing to the platform’s fulfillment of social expectations of stakeholders, both internal and external to the ecosystem. The underlying premise is that ESR serves to achieve societal goals through social value co-creation of ecosystem partners, instead of economic value co-creation that underpins the platform business; frictions will dampen social value co-creation while synergies will enhance it. The idea of ESR departs from the case of GVCs where CSR is framed largely from the lead firm’s viewpoint (Kim & Davis, 2016), as well as the case of MNEs where accounts of CSR often refer to the foreign subsidiary’s activities (Marano et al., 2017; Zhou & Wang, 2020). Rather, we echo the tenet of the collective action literature which views an organization as a community of enfranchised stakeholders (Klein, Mahoney, McGahan, & Pitelis, 2019). The purpose of organizing a platform is to deploy the co-specialized assets and capabilities of enfranchised stakeholders who cannot independently realize the same amount of value. Collective action problems arise when different stakeholders within the organization attend to diverse goals which are primarily to protect and pursue their self-interests (Ostrom, 1990). While it is widely recognized that platform governance is key to resolving the collective action problem in economic value creation (Chen et al., 2022b), we maintain that it plays an equally crucial role, if not more so, in aligning enfranchised stakeholders with generating positive externalities and against negative externalities, regardless of economic gains for them.

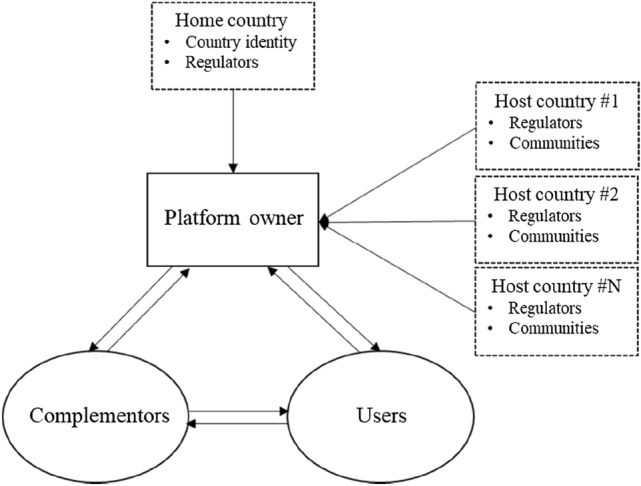

To elaborate, Figure 1 maps out the relationships. In a platform ecosystem, while all parties (e.g., platform owners, complementors, and users) would be considered legitimate claimants (and thus stakeholders) to ecosystem social responsibility, each may pay attention to distinct social issues arising from its interplay with other parties. On the one hand, these stakeholders, such as the complementors noted above, have the right to demand socially acceptable behaviors from others with whom they interact. On the other hand, they are also subject to, and must respond to, the institutional demands to which the other parties are entitled. The responses are driven by concerns of legitimacy both within the platform ecosystem and in the eyes of external stakeholders. Internal and external stakeholders’ demands may prompt critical parties to engage in pro-social actions, setting in motion a synergistic force across all interacting parties that will ultimately strengthen ecosystem social responsibility. For instance, advertisers (e.g., Unilever), from whom social platforms like Facebook and YouTube accrue revenue, have demanded those platform firms to crack down on illegal and extremist content, because of the former’s own consumer pressure; consumers are losing trust in brands that place ads next to misinformation.6 However, because of the collective action problem, enfranchised stakeholders (e.g., content creators) may also be resistant to change when they perceive not to gain personally from the adaptation, despite the envisaged benefits for the entire ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Stakeholders of a multinational platform; the arrow denotes a legitimate claimant to the pointed party.

The idea of ESR implies that social issues associated with platforms will exhibit greater diversity and complexity than those studied in the CSR literature (e.g., CSR reporting and philanthropy), due to the extensive participation and interactions of complementors and users in an ecosystem, and to the externalities of their interactions with stakeholders outside the ecosystem, such as local communities and governments. Building on Porter and Kramer (2006)’s idea embedding firms’ social responsibility in broader contexts, we develop a framework to consider three distinct categories of social issues that are associated with platform ecosystems (see Figure 2), as we further enrich the concept of ESR in the international setting. First, ecosystem social impacts refer to social issues that arise from a platform’s activities in the ordinary course of business, impinging upon stakeholders within the ecosystem (but outside the platform firm). While this category represents social frictions between ecosystem participants, the main concerns center on various forms of mistreatment of complementors and users by the platform firm (Cutolo & Kenney, 2021; Karanović, Berends, & Engel, 2021). For instance, some e-commerce platforms from weakly regulated countries provide sponsored listing of sellers, yet do not disclose such sponsorship, effectively releasing a deceptive signal to buyers in other countries and increasing frictions between buyers and sellers (Deng, Liesch, & Wang, 2021). Second, social dimensions of competitive context primarily consider factors in the external environment that significantly affect the underlying drivers of competitiveness in those places where the platform operates (Garud, Kumaraswamy, Roberts, & Xu, 2022). Issues ranging from emergent regulation, media scrutiny, and incumbent resistance in the target market may undermine the economic feasibility of a platform organization or impede the platform firm’s ability to carry out its strategy (Aversa, Huyghe, & Bonadio, 2021). They often compel platform firms to adapt private governance in better delivering a declared value proposition and realizing the promised social impact (Carrasco-Farré, Snihur, Berrone, & Ricart, 2022). Finally, general societal issues refer to those that emerge with the growth of the digital economy in general, and are not tied directly to a platform’s short-term operations, such as the grand challenges faced by society (Montiel, Cuervo-Cazurra, Park, Antolín-López, & Husted, 2021). For example, the expansion of Uber into an area tends to reduce alcohol-related motor vehicle fatalities (Greenwood & Wattal, 2017), while P2P lending platforms are found to lift financial and social barriers to abortion as a result of their host-market entry (Ozer, Greenwood, & Gopal, 2022). Conversely, the entry of classified ad sites like Craigslist can serve as online intermediaries for casual sex and hence increase HIV transmission (Chan & Ghose, 2014). Table 3 provides further examples of the three categories based on familiar MNPs. Next, we illustrate the implications of this ESR framework for IB research and seek to understand the challenges in international operations faced by different firms organizing two archetypal types of MNPs.

Figure 2.

Three categories of social issues for an ecosystem.

Table 3.

Three categories of social issues for MNPs

| Categories of social issues | Examples |

|---|---|

| Ecosystem social impacts | Complementor mistreatment (Apple/UberEats); labor exploitation (DoorDash/Gojek); inappropriate content (Tumblr); user privacy (Facebook); censorship (WeChat); environmental footprint (SHEIN); algorithm transparency (TikTok) |

| Social dimensions of competitive context | Antitrust scrutiny (Google); industrial regulation (Airbnb); incumbent challenge (Uber/Ola); misinformation charge (Twitter), IP protection (Instagram); alternative job for complementors (Bolt); physical infrastructure (Amazon/Alibaba); input conditions (Microsoft Hackathon) |

| General societal issues | Democracy and division; cybersecurity; digital literacy and divide; disaster relief; energy consumption; poverty reduction; technology misuse |

Social challenges for multinational platforms

Prior literature reveals significant heterogeneity between global platforms (Nambisan, Zahra, & Luo, 2019; Stallkamp & Schotter, 2021). Some serve host-country users with host-country complementors, and are thus characterized by bounded network effects, resembling a multidomestic strategy (Chen, Shaheer, Yi, & Li, 2019). Others operate on a global scale and orchestrate an interconnected network across countries (Zhu, Li, Valavi, & Iansiti, 2021), and they tend to penetrate new host-country markets to acquire local users that are drawn to globally-sourced complements (Shaheer & Li, 2020). Hennart (2019) attributes such heterogeneity to the varying economies of scale with which a digital service can be fulfilled. While scholars have discussed the entry strategy and economic outcomes associated with the different platforms (Chen et al., 2022a), we know little about the implications for platform legitimacy and social responsibility demands. To probe into ESR, we broadly categorize MNPs into global platforms and multidomestic platforms in reference to their local embeddedness, in line with Brouthers et al. (2022).

According to the network literature, firms’ activities and outcomes are embedded in, and shaped by, their interorganizational relationships (Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1996). Embeddedness is a function of the firm’s reliance on stakeholders (such as suppliers, customers, and complementors) in obtaining the use of critical resources beyond arm’s-length relationships (Saxton, 1997). For firms operating in multiple international markets, the local context is considered the institutional framework and resource base that the firm can access in exploiting existing competences and creating new competences (Meyer, Mudambi, & Narula, 2011). Following this line of thinking, we define local embeddedness by the extent to which the firm is anchored in a particular space to generate local networks of economic and social relationships (Hess, 2004).

As global platforms and multidomestic platforms have varying levels of local embeddedness (low vs. high), we expect that their primary challenges differ in grappling with the three categories of social issues. In line with the latest research (Altman, Nagle, & Tushman, 2022; Chen, Tong, et al., 2022), we employ a platform firm-centric perspective, given the importance of the (private) governance role that the firm assumes for joint value creation. This echoes Hennart’s (2019) contention that the extent to which the platform owner can control excessive free-riding on quality by complementors determines whether organizing as a platform is more efficient than hierarchy (i.e., employing the complementors). When shirking by employees outweighs the consequence of complementors’ free-riding, platform organizations emerge. In a similar vein, we submit that positive ESR ensues when social synergies outweigh social frictions, and that in turn depends on how effectively the platform firm can govern the ecosystem in response to various social challenges. Our new insights thus focus on the governance aspect for firms orchestrating global platforms and multidomestic platforms, respectively.

Proposed Insights

Global platforms represent those that primarily utilize the pool of globally-sourced complementary products in penetrating host-country markets (Brouthers, Geisser, & Rothlauf, 2016; Chen et al., 2019). This category to some extent resembles service exporting, in that the MNP can reach host-country users without committing a discrete market entry event. Nevertheless, unlike exporting where internationalizing firms proactively explore foreign business opportunities, host-country users on a global platform value, and are therefore drawn to, the opportunities to interact and transact with foreign complementors offering tangible or information goods. That allows global platforms to achieve a high degree of internationalization in a short period of time, in terms of the number and variety of host countries served, as well as a high level of interconnectedness between ecosystem participants from different countries.

With regard to ecosystem social impacts, global platforms are likely to face friction between complementors and users on a global scale. Researchers have shown that internationalization increases firms’ embeddedness in meta-institutional fields, which may reshape their identity into global actors such that they attend more to global institutional pressures (Marano et al., 2017; Tashman et al., 2019). Prior research also suggests that MNEs may build a global social brand and diffuse responsible behaviors across the network of foreign subsidiaries (Asmussen & Fosfuri, 2019). In a similar vein, global platforms are likely to establish a coherent set of social norms and standards for participation in a focal ecosystem (Chen et al., 2022b). For example, Flickr publishes Community Guidelines using plain language to convey what is expected of their users, including “Things to do” (e.g., “Play nice”, and “Only upload content that you have created”), as well as “Things not to do” (e.g., “Don’t use hate speech”, and “Don’t harass other users”).7 Creating reminders of community norms throughout the platform may be one approach to effective enforcement, in the absence of fiat (Culatta, 2021). To this end, whether these norms can be enforced depends not only on the platform firm’s technological capability but also on its governance capability. This is an area where MNPs can gain a competitive advantage and reap business benefits through strategic ESR (Kolk & Pinkse, 2008), which may be changes in the business model or platform designs that are geared toward greater social synergies and in pursuit of differentiation from rival platform ecosystems. For example, those global platforms that can accommodate the expectation of ecosystem participants from more socially demanding countries would establish a higher ecosystem standard for all participants and therefore attain greater social performance.

Insight 1a:

For firms governing a global platform, the challenge regarding “ecosystem social impacts” centers on establishing and enforcing ecosystem-wide norms that are accepted by complementors and users around the world.

Social dimensions of competitive context are a major source of local institutional demands that condition a platform’s operations in a host country. Prior research shows that local CSR is less common when firms adopt a global strategy; this may be partly because of lack of managerial attention and resources devoted to individual country markets (Mezias, 2002), as well as internal structures that are in favor of integration instead of responsiveness (Husted & Allen, 2006). More strikingly, international diversification could be positively associated with social irresponsibility because of monitoring and coordination costs (Strike et al., 2006). While scholars have entertained the idea that limited local embeddedness is inherently conducive to platform internationalization (Autio, Mudambi, & Yoo, 2021), we caution that the lack of embeddedness may not only be a source of illegitimacy but also hamper MNPs’ ability to improve ESR. This is because the incidence of unexpected demands by local stakeholders may be positively associated with institutional diversity, which is characteristic of global platforms. The extent to which firms orchestrating a global platform will attend to and promote local ESR may be a function of host-country institutions. While traditional MNEs tend to commit more CSR in weak institutions in gaining social licenses (Hornstein & Zhao, 2018), we expect greater demands for social responsibility in countries where rules and collective norms are stronger (Ioannou & Serafeim, 2012; Rathert, 2016). This is due to the discrepancy between the ecosystem-wide norms established and the host-country’s more advanced and sophisticated social expectations that may require specific social adaptation (Zhao, Park, & Zhou, 2014). ESR in this category may be responsive or strategic, depending on whether the platform can effectively internalize higher social standards into ecosystem-wide norms that condition transactions and interactions on the platform, such that social and business benefits can be integrated into a unified value proposition (Carrasco-Farré et al., 2022). For instance, Kiva, a global micro-finance platform linking developing-country borrowers with developed-country lenders, introduces a “social performance” badging program to encourage loan projects in areas that Kiva considers important, such as empowering women. This program has led to improved end-user demand and financial performance for the platform, and for those badged complementors that align their product portfolio with the objective of this program (Rietveld, Seamans, & Meggiorin, 2021).

Insight 1b:

For firms governing global platforms, the challenge regarding “social dimensions of competitive context” centers on accommodating unexpected demands arising from institutional diversity, and on prioritizing stakeholder expectations in countries where norms and regulations are stronger.

Global platforms are more likely to attend to general societal issues because of their international outlook, but may also more likely be held to account because of their global operational scale. ESR activities in this category are attuned to the evolving social concerns of global stakeholders, and often developed through corporate citizenship initiatives. Platforms that can demonstrate their advantage over traditional firms and non-profit organizations in mobilizing ecosystem resources, to address pressing social issues and achieve measurable goals, will be able to harvest goodwill and improve reputation. Such social capital, embedded in the enhanced legitimacy of a platform organizational form, may help the firm temper public criticism in the event of a crisis that affects its main business. In this sense, effective ESR initiatives addressing globally relevant social concerns may be of strategic value for firms orchestrating global platforms. For instance, a creative social media campaign prompted people from around the world to offer direct support for war victims by paying for Airbnb rentals in Ukraine that they have no plan to visit.8 Inspired by this grassroots initiative, Airbnb formalized the donation channel with a dedicated mission platform and waived all fees in the country. A campaigner then expanded the initiative to Etsy, and Etsy, too, endorsed it by cancelling fees owed by all sellers in Ukraine. In contrast, the negative externalities of an online platform business on the offline society – for example, increased racial hate crimes populated by information platforms (Chan & Ghose, 2014) – may lead to wide debates about the net societal impact of platforms, and likely undermine the legitimacy of such a new organizational form.

Insight 1c:

For firms governing global platforms, the challenge regarding “general societal issue” centers on demonstrating the advantage of platform organization in addressing globally relevant social concerns.

A locally embedded platform, such as Uber, must rely on the resources of host-country complementors (e.g., services) and host-country users (e.g., consumer data) to create value, and it is likely to establish foreign subsidiaries to oversee host-country operations, resembling a multidomestic strategy that some traditional MNEs adopt. This is the platform organizational form that will confront MNPs with strong legitimacy challenges and requirements for local ESR because of extensive connections with local stakeholders (Hornstein & Zhao, 2018). Researchers argue that firms operating in more visible industries face greater institutional pressure than do those in less visible industries (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006). Visibility increases as the operations involve high levels of employment, customers, and revenue in the local economy (Rosenzweig & Singh, 1991; Young & Makhija, 2014).

When an MNP’s organizational form relies primarily on local complementors to serve local users, it tends to play a salient role in determining the former’s economic interests and the latter’s consumer utility as network effects gather strength. What seems understated is the platform’s ability to shape these local actors’ social welfare, i.e., ecosystem social impacts, and the fact that it will be held liable for the harm it can cause, some of which are nonetheless a result of complementors or users’ irresponsibility instead of the platform firm’s own wrongdoing. On the other hand, multidomestic platforms may seek to improve corporate image and shape public perception by emphasizing how their organizational form and local operations have offered an alternative solution to a salient societal problem or introduced positive changes to the status quo, e.g., providing revenue-earning opportunities for marginal workers, or improving transaction efficiency. This may be a proactive tactic for multidomestic platforms to shirk social consequences of their operations for societal members, and it tends to work more effectively in countries where the existing institutional infrastructure (i.e., the alternatives available to ecosystem participants) is less developed (Ghoul, Guedhami, & Kim, 2017; Uzunca, Rigtering, & Ozcan, 2018). In countries with stronger institutions, the proclaimed social benefits of a platform organizational form might be unable to outweigh the social cost that ecosystem participants must bear. That would require greater investment by the platform firm to mitigate negative social impact on ecosystem participants, so as to attain a given level of ESR. All in all, ESR initiatives in this category will be primarily responsive (i.e., to mitigate harm), and centers on increasing net social benefits that a platform provides for local ecosystem participants.

Insight 2a:

For firms governing multidomestic platforms, the challenge regarding “ecosystem social impacts” centers on increasing net social benefits for local complementors and users.

Whether multidomestic platforms can operate effectively depends heavily on the local competitive context. For example, ESR plays a crucial role in gaining local social licenses (Hornstein & Zhao, 2018), such that new complementors will continue to join the platform. The winner-take-all outcome resulting from local network effects may exacerbate concerns from regulators in such areas as monopolistic market power and consumer protection. The fact that such dominating power, along with a highly efficient information aggregation ability enabled by digital technology, allows the MNP to provide public goods and services in domains traditionally served by government, may jeopardize the platform’s perceived legitimacy, and lead to the liability of privateness (Bhanji & Oxley, 2013). Researchers have argued that the perceived threat of state intervention compels firms to engage in locally relevant CSR, or so-called industrial self-regulation, in ways that can institutionalize local stakeholders’ expectations (Campbell, 2007).

However, institutional distance between home and host country may result in knowledge gaps and a lack of institutional embeddedness, amplifying liabilities of foreignness for a multidomestic platform. Research has shown that firms are less likely to engage in CSR in distant countries because of reduced willingness and the ability to do so (Campbell, Eden, & Miller, 2012). We expect ESR initiatives in this category to create strategic value when a multidomestic platform can pre-empt local stakeholders’ concerns by integrating social initiatives (instead of cosmetic changes) into its governance rules (Garud et al., 2022). For instance, a platform may prevent grassroots resistance in a local market through dedicated governance designs. that can align collective interests of ecosystem participants as well as others in the community, i.e., non-participants (Ricart et al., 2020). Since local stakeholders’ specific demands can apply to many platforms, multidomestic platforms may even partner with local or foreign rivals in establishing industry standards for platforms operating in the same market category in a host country. Meanwhile, the perceived legitimacy issues and the associated stakeholder expectations may spillover from one country to another (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Zhou & Wang, 2020). We also expect that ESR can be of strategic value when multidomestic MNPs transfer knowledge from operations in one country to another, instead of responsive actions. Embedded in organizational practices, such knowledge may include how to build relationships with regulators through various channels and to pre-empt adverse regulations (Uzunca et al., 2018), and it can constitute a key source of competitive advantage for a platform.

Insight 2b:

For firms governing multidomestic platforms, the challenge regarding “social dimensions of competitive context” centers on maintaining legitimacy through locally adapted changes to the governance rules that can incorporate social initiatives, such that the greater the institutional distance between home and host countries, the more substantive governance changes may be required.

Multidomestic platforms are locally embedded in acquiring resources and social capital that are critical to their long-term sustainability. In addressing grand social issues that are not immediately related to a platform’s local operations, but may be brought about by the growing economy in general, platform firms may nonetheless commit ESR initiatives, such as philanthropic contributions to social causes that are relatively more connected with the platform’s strategy, instead of areas in which the firm has little expertise and resource. Yet, regardless, such commitment tends to rely on the coordination by a local subsidiary, and it may be caught in the conflicting pressures between headquarters and subsidiary that are typical of traditional MNEs (Durand & Jacqueminet, 2015), because of unclear long-term benefits to the platform ecosystem.

Insight 2c:

For firms governing multidomestic platforms, the challenge regarding “general societal issues” centers on coordinating initiatives that address wider social concerns specific to the host society.

Directions for future research

Research Questions to Be Explored

As our informed conjectures provide a starting point illuminating social dimensions of digital globalization, they open up numerous avenues for future research in bridging the gap between digitalization and CSR (see Table 4). In respect of ecosystem social impact, a promising lead is to unveil the specific governance rules and technical designs that global platforms deploy in establishing and enforcing ecosystem-wide social norms (Asmussen & Fosfuri, 2019). The underlying mechanism may still revolve around the governance dimensions of incentive and control (Chen, Tong, et al., 2022), yet the goal of governance could well depart from the case of global supply chain governance which centers on the maximization of comparative efficiency (Strange & Humphrey, 2018). While maintaining a globally integrated social standard, global platforms are likely to confront idiosyncratic expectations from host-country ecosystem participants which may incur additional cost to fulfill. Prior CSR research has paid much attention to the balance between integration and responsiveness for MNEs (Durand & Jacqueminet, 2015) and the cost implications (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001). Whether our received wisdom applies to global platforms which orchestrate a network of stakeholders characterized by tremendous levels of institutional diversity remains to be investigated. Conversely, for multidomestic platforms, it is conceivable that some will continue to emphasize the social benefit their disruptive business model confers on local stakeholders (Aversa et al., 2021), while seeking to downplay the social cost incurred. A key question to be explored is how exactly the institutional environment of a host country influences the perceived social impact that the platform imposes on local ecosystem participants. Furthermore, we encourage future research to extend and contextualize ecosystem social impact in the asymmetric relationship between focal MNEs and startup partners (Buckley & Prashantham, 2016), which appears of particular relevance to fulfilling the sustainable development goals (Prashantham & Birkinshaw, 2020) and to the diffusion of digital sustainability practices (George, Merrill, & Schillebeeckx, 2021).

Table 4.

Future research questions

| Global platforms | Multidomestic platforms | |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem social impacts |

What platform governance rules and designs do global platforms deploy to establish and enforce ecosystem-wide norms? How do they differ from global supply chain governance? How do global platforms balance the globally integrated ecosystem norm and idiosyncratic expectations by host-country ecosystem participants in maintaining both ESR standards and additional costs? |

To what extent and when can multidomestic platforms improve ESR by only emphasizing the social benefit the organizational form enables? How does the perceived level of social impact multidomestic platforms have on ecosystem participants depend on the institutional environment of a host country? |

| Social dimensions of competitive context |

How does institutional diversity affect the legitimacy of global platforms’ organizational form? How does institutional distance affect global platforms’ social performance and competitiveness in a host country? Why do global platforms engage more in ESR initiatives in stronger institutions, as opposed to MNEs’ stronger CSR commitment in weaker institutions? |

What elements of the governance rules do multidomestic platforms commonly adjust in response to local stakeholders’ demands? What is the role of non-market strategy in multidomestic platforms’ management of local stakeholder relationships? |

| General societal issues |

Under what circumstances are global platforms more efficient in addressing general societal issues than NGOs and governments? When and to what extent does global platforms’ investment in addressing global societal issues generate strategic value? |

How does entry mode of high versus low commitment affect multidomestic platforms' ability and effectiveness in committing ESR initiatives that address locally relevant, general societal issues? How do multidomestic platforms choose peer groups in conforming to expectations of general societal ESR? |

Regarding social dimensions of competitive context, global platforms face high degrees of complexity in managing the institutional field they establish (i.e., the ecosystem) because of institutional diversity. The interactions between host-country users and third-country complementors, while being part of a global platform’s core value proposition, may elicit concerns from host-country stakeholders, such as regulators, and impair the platform’s local legitimacy. It remains to be seen whether it is institutional distance between home and host country or the absolute level of host-countries’ institutional expectation that will amplify the legitimacy challenge. For multidomestic platforms, social dimensions of competitive context pose a greater threat to their business performance because of more substantial local embeddedness, calling for locally adapted ESR initiatives. Future research could illuminate the specific means of social adaptation (Zhao et al., 2014); some multidomestic platforms may adjust certain elements of the governance rules in response to local stakeholders’ social demands, while others may deploy non-market strategy to manage stakeholders’ perceptions and navigate institutional complexity in different country markets (Sun et al., 2021). Given the fragmentation of GVCs and their interface with diverse local contexts, we also encourage IB scholars to account for a more prominent role of social dimensions of competitive context in the traditional frameworks for networked organizations (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004; Doz, Santos, & Williamson, 2001; Rugman & D'Cruz, 1997)

Finally, one of the key questions regarding general societal issues is the conditions under which global platforms are more efficient in mobilizing resources at scale to address social issues than national governments or non-government organizations (NGOs). The platform organizational form has proved efficient in aggregating information and resources for economic value creation, and it is not hard to envisage its potential in realizing social value through digital transformation (Rauch & Ansari, 2022). We have seen global platforms devote resources to grand societal challenges like pandemic relief and climate change. On the rise are also platforms like Amnesty Decoder, which is driven by a social mission and deploys collective solutions against sustainability problems (Logue & Grimes, 2022). How much social impact these initiatives and solutions really create, and how social-mission platforms and for-profit platforms differ in design and impact, await future research to explore. Conversely, multidomestic platforms would more attend to societal issues that concern local stakeholders in pursuit of acceptance. It would be fruitful to examine whether serving a host country with a high-commitment entry mode (e.g., having a full-fledged subsidiary) will improve the effectiveness of undertaking ESR initiatives that are remotely related to the main business, or whether greater levels of institutional embeddedness can exempt the firm from investing in general societal ESR. Given the ambiguous social impact and economic return of general societal ESR, multidomestic platforms’ commitment may be driven by mimetic isomorphism instead of a proactive strategy. We imagine that how technology firms choose peer groups to which to conform would be a question of continued interest.

Theoretical and Empirical Challenges Ahead

For future research advancing ESR, the foremost challenge lies in explaining the mechanisms driving social frictions and social synergies among ecosystem partners which ultimately lead to social value co-creation (or co-destruction). Platform research has extensively discussed economic value co-creation as one of the defining features of such meta-organizations. The prospect of a higher return from value co-creation keeps loosely-coupled partners committed, and prompts them to make specific investments that can enhance the projected return (Tong, Guo, & Chen, 2021). Mutual commitment will kick in network effects and a self-reinforcing feedback loop leading to ever greater economic value. Whether this mechanism can map onto social dimensions is unclear. It may be that complementors’ higher social performance would appeal to more users and vice versa. However, what seems more likely is a collective action problem that prevents ecosystem participants from making meaningful investment in social responsibility, which could erode economic returns or deliver dubious social impacts. Mutual social commitment may be hard to sustain, as MNPs are particularly vulnerable to partners’ bounded reliability (Verbeke & Greidanus, 2009). Accounting for institutional complexity and diversity in different country markets may be the first step toward understanding sources of social frictions and ecosystem social irresponsibility.

Meanwhile, how the platform firm can devise rules and incentive structures to mitigate frictions and maximize areas of synergy has yet to be delineated in the platform governance literature, which only considers economic value as the goal of governance (Chen, Tong, et al., 2022). The platform firm’s governance capability may determine whether social synergies can be realized in distinct institutional environments, and it may be an important but understated antecedent of ecosystem-specific advantages. Finally, social issues in the platform context are in a fluid state because of a lack of institutionalization in technology industries and of an imperative to contain platforms’ power. The public’s expectations around a given issue may evolve rapidly, e.g., one that starts gathering media awareness may quickly turn into voluntary initiatives in the face of increasing institutional pressure, and voluntary initiatives in one country may arouse a call for legislation in another. Relatedly, high-profile complementors (e.g., influencers on Spotify and Twitch) that have a sizable fanbase may influence the platform’s private governance; their social demands could diffuse across the platform ecosystem, while their own social performance, as scrutinized by the public, may prompt the platform owner to impose a more stringent code of ethics. These ongoing observations pose the question of whether social actions are still driven by isomorphism in a nascent institutional field. Future research will enjoy opportunities to unsettle our received understanding of CSR which rests on isomorphism.

On the empirical front, the biggest challenge stems from the measurement of ESR behaviors and performance. Given how a firm’s social performance is often captured in prior research, it is not inconceivable to rate a platform’s social performance along various ESG dimensions, particularly regarding its impact on ecosystem participants (as opposed to traditional supply chain partners). However, relying on familiar firm-level measures misses out on the important interplays between actors in the ecosystem which, as we have argued, differentiate ESR from CSR. We suggest that future research employ more nuanced research design to infer the level of social performance of a platform. For example, a heated debate regarding ecosystem social impacts centers on whether platform owners misuse their extensive power in determining complementors’ commercial success through opaque algorithms and content curation (Cutolo & Kenney, 2021). In an empirical study, Aguiar, Waldfogel, and Waldfogel (2021) have investigated whether Spotify, the music streaming platform, biases against independent labels and women musicians in ranking songs in their largest playlists. By comparing the platform’s ex ante ranking of songs and the songs’ ex post performance, the study shows that, contrary to common perceptions, platforms may disproportionately promote work from minority groups. The study offers evidence of positive social performance that is not reflected in ESG indices. With regard to social dimensions of competitive context, Aversa et al. (2021) employed a longitudinal comparative case study to reveal the genesis of divergent social acceptance facing Uber and BlaBlaCar. The study traces the linkage between categorization strategies and the varied responses from non-market stakeholders, such as media and regulators, which ultimately determine the legalization and feasibility of a platform business. In studying general societal issues associated with platforms, Han et al. (2022) empirically exploit policy changes in certain cities that reduce the number of Airbnb listings. The authors find causal evidence that removing commercial host listings leads to on average a 5% reduction in neighborhood crimes, including assault, robbery, and burglary, yet an increase in theft incidents. The research design allows the authors to infer the societal impacts of platform self-regulation, something that cannot be captured by traditional ESG metrics.

Furthermore, whether a voluntary social initiative should be framed as an ESR behavior or non-market strategy in an empirical study seems increasingly ambivalent (Hillman & Keim, 2001). Prior research leans toward the view that social initiatives, especially those mitigating impact on ecosystem participants, are strategic actions that platform owners deploy to comfort salient stakeholders, or are reactive responses to ecosystem participants’ growing dissatisfaction (Garud et al., 2022). Future empirical studies may investigate where and how social initiative can most effectively yield strategic value (e.g., maximizing reputation and goodwill), while taking into account the endogenous nature of ESR responses. Finally, much empirical CSR research has been devoted in the possible relationship between a firm’s social performance and its financial performance, which makes the case for why firms engage in social initiatives. Similarly, in the context of platforms, whether and why a platform ecosystem’s social performance can be translated into sustainable ecosystem-specific advantage may be the ultimate empirical question to answer.

Implications for Ecosystem Sustainability

Extant CSR research has made numerous cases for why firms engage in pro-social actions and provides various explanations for the observed or assumed relationship between CSR and financial performance. Implicit in this research is a premise that CSR is conducive to the sustained advantage of a business and should be seen as an investment. On the other hand, platform research has paid extensive, if not exclusive, attention to the sustainability of a platform business from the perspective of economic value creation (Rietveld & Schilling, 2021). Consensus emerges that platform businesses can remain prosperous once network effects set in and stay strong. Piecing these received views together, one might wonder why platforms would commit to ESR when the economic value of the platform ecosystem is never reinforced by a positive feedback loop. The lack of social responsibility, as seen among the leading MNPs of our time, may not be a coincidence after all.

However, the latest Facebook saga reminds us that economic value creation or network effects by no means guarantee sustainable businesses. On the contrary, platforms that succeed in growing a large and interconnected network may well be rendered more visible to external stakeholders, while encountering social issues that are more complex than ever. MNPs have been blamed for bad deeds, like human trafficking, that may be pervasive in the society, but much amplified by the digital technology. These accusations reflect the liability of privateness for MNPs as well as an unprecedented level of social expectations for private firms. Ultimately, linking CSR and platform research reveals a paradox of economic versus social value creation for MNPs. Thus, pursuing winner-take-all outcomes in the short term, as platform scholars constantly advise, may give rise to social challenges that deprive the platform of opportunities of long-term business success. In this sense, ESR should carry even greater strategic value than traditional CSR, in that collaborating with internal and external stakeholders to establish and enforce sufficient social standards may be the only way to preempt government intervention and to preserve a platform organizational form. Conversely, a passive ESR response that prioritizes growth and profit at the cost of social impact can put an end to a thriving ecosystem, like the one that Napster – a pioneering P2P music sharing platform – once built. Thus, it is our contention that the tradeoff between profit and social value is a mis-specified one, as only those MNPs that invest in sound private governance will remain profitable in the long term and retain the license to operate in international markets.

Conclusions

This paper yields new insights into how platform ecosystems present not only a new unit of analysis for examining internationalization but also a unique context for extending global CSR research. We demonstrate this potential by pointing out three fronts on which future research can extend the pioneering work of Ioannou and Serafeim (2012). First, we show that the complexity of ecosystems as a new form of value chain organization expands the locus of social responsibility from a focal firm to a network of interdependent yet enfranchised ecosystem participants. Second, our proposed insights into MNPs account for the portfolio of host countries and the diverse interfaces with local contexts. The prevalence of MNPs will require future research to extend beyond the home-country impacts on which Ioannou and Serafeim (2012) focus, and to consider the embeddedness with a myriad of host-country stakeholders. Finally, we reflect on the empirical challenges in advancing this research agenda and offer guidance for future studies. Instead of relying on the convenient ESG metrics, we demonstrate how scholars may engage nuanced research design to reveal MNPs’ social performance. We believe that the IB community will continue to find this research avenue a promising one as they further the concept of ecosystem social responsibility, as well as dissect the specific ways in which platform firms and ecosystem participants fulfill stakeholder expectations and address societal goals through social value co-creation.

Notes

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/27/technology/eu-google-fine.html.

https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/update-facebook-antitrust-lawsuit/.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jul/12/facebook-fine-ftc-privacy-violations.

As of March 13 2022, around 36,000 people from 160 countries have signed up (source: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/15/opinion/russia-ukraine-putin-war.html).

https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/ukraine-airbnb-donations-cec/index.html.

.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editor-in-Chief Alain Verbeke and two anonymous reviewers for their excellent comments. Jingtao Yi is grateful for the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 71873136. Jiatao Li is grateful for the financial support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (HKUST# 16507219) and HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies (IEMS) Research Grant (IEMS21BM05).

Biographies

Jingtao Yi

is a Professor of Economics, School of Business, Renmin University of China. His research interests lie at internationalization strategy, emerging market multinationals, innovation and international business, and international business in the digital economy, with a focus on platform ecosystems, platform competition, and globalization. His work has been published in Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Management, and Journal of Management Studies, among others.

Jiatao Li

is Chair Professor of Management, Lee Quo Wei Professor of Business, Director of the Center for Business Strategy and Innovation, and Senior Fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. He is a Fellow of the AIB and an editor of the Journal of International Business Studies. His current research interests are in the areas of organizational learning, strategic alliances, corporate governance, innovation, and entrepreneurship, with a focus on issues related to global firms and those from emerging economies.

Liang Chen

is Associate Professor of Strategic Management at the Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University. His research focuses on platform ecosystems and digital innovation, corporate strategy, and global strategy. He is a JIBS editorial board member, and an editor of IBR, MOR, and JIM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Alain Verbeke, Editor-in-Chief, 24 July 2022. This article was single-blind reviewed.

All three authors contributed equally. The authorship is listed in reverse alphabetical order.

Contributor Information

Jingtao Yi, Email: yijingtao@rmbs.ruc.edu.cn.

Jiatao Li, Email: mnjtli@ust.hk.

Liang Chen, Email: liang.chen@unimelb.edu.au.

References

- Adner R. Ecosystem as structure. Journal of Management. 2017;43(1):39–58. doi: 10.1177/0149206316678451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar L, Waldfogel J, Waldfogel S. Playlisting favorites: Measuring platform bias in the music industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization. 2021;78:102765. doi: 10.1016/j.ijindorg.2021.102765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albino-Pimentel J, Oetzel J, Oh CH, Poggioli NA. Positive institutional changes through peace: The relative effects of peace agreements and non-market capabilities on FDI. Journal of International Business Studies. 2021;52(7):1256–1278. doi: 10.1057/s41267-021-00453-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altman EJ, Nagle F, Tushman ML. The translucent hand of managed ecosystems: Engaging communities for value creation and capture. Academy of Management Annals. 2022;16(1):70–101. doi: 10.5465/annals.2020.0244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen CG, Fosfuri A. Orchestrating corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise. Strategic Management Journal. 2019;40(6):894–916. doi: 10.1002/smj.3007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Autio E, Mudambi R, Yoo Y. Digitalization and globalization in a turbulent world: Centrifugal and centripetal forces. Global Strategy Journal. 2021;11(1):3–16. doi: 10.1002/gsj.1396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aversa P, Huyghe A, Bonadio G. First impressions stick: Market entry strategies and category priming in the digital domain. Journal of Management Studies. 2021;58(7):1721–1760. doi: 10.1111/joms.12712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banalieva ER, Dhanaraj C. Internalization theory for the digital economy. Journal of International Business Studies. 2019;50(8):1372–1387. doi: 10.1057/s41267-019-00243-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry H, Kaul A, Lee N. Follow the smoke: The pollution haven effect on global sourcing. Strategic Management Journal. 2021;42(13):2420–2450. doi: 10.1002/smj.3288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanji Z, Oxley JE. Overcoming the dual liability of foreignness and privateness in international corporate citizenship partnerships. Journal of International Business Studies. 2013;44(4):290–311. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2013.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brouthers, K. D., Chen, L., Li, S., & Shaheer, N. 2022. Charting new courses to enter foreign markets: Conceptualization, theoretical framework, and research directions on non-traditional entry modes. Journal of International Business Studies, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brouthers KD, Geisser KD, Rothlauf F. Explaining the internationalization of ibusiness firms. Journal of International Business Studies. 2016;47(5):513–534. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2015.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PJ, Doh JP, Benischke MH. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies. 2017;48(9):1045–1064. doi: 10.1057/s41267-017-0102-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PJ, Ghauri PN. Globalisation, economic geography and the strategy of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies. 2004;35(2):81–98. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PJ, Prashantham S. Global interfirm networks: The division of entrepreneurial labor between MNEs and SMEs. Academy of Management Perspectives. 2016;30(1):40–58. doi: 10.5465/amp.2013.0144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JL. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review. 2007;32(3):946–967. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.25275684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JT, Eden L, Miller SR. Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies. 2012;43(1):84–106. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2011.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Farré C, Snihur Y, Berrone P, Ricart JE. The stakeholder value proposition of digital platforms in an urban ecosystem. Research Policy. 2022;51(4):104488. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2022.104488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Ghose A. Internet’s dirty secret: Assessing the impact of online intermediaries on HIV transmission. MIS Quarterly. 2014;38(4):955–976. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.4.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Li, S., Shaheer, N., & Stallkamp, M. 2022a. 3 obstacles to globalizing a digital platform. Harvard Business Review, May 3.

- Chen, L., Li, S., Wei, J., & Yang, Y. 2022b. Externalization in the platform economy: Social platforms and institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, in press.

- Chen L, Shaheer N, Yi J, Li S. The international penetration of ibusiness firms: Network effects, liabilities of outsidership and country clout. Journal of International Business Studies. 2019;50(2):172–192. doi: 10.1057/s41267-018-0176-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tong TW, Tang S, Han N. Governance and design of digital platforms: A review and future research directions on a meta-organization. Journal of Management. 2022;48(1):147–184. doi: 10.1177/01492063211045023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]