Abstract

Mononeuritis multiplex is a rare form of cerebral nerve palsy caused by various factors. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination could be an etiology of mononeuritis multiplex, which can affect various nerves. Post-COVID-19 and vaccination-related neurological impairments involve cranial nerves such as the facial, trigeminal, and vagal nerves. We report our experience with a 34-year-old man who developed hypoglossal nerve palsy following COVID-19 vaccination, complicated by progressive mononeuritis multiplex. Hypoglossal nerve palsy may occur following COVID-19 vaccination. The symptoms vary and may progress without treatment. Physicians should consider the possibility of mononeuritis multiplex after COVID-19 vaccination and provide prompt treatment for acute symptom progression.

Keywords: general medicine, rural hospital, extremity paralysis, immunoglobulin infusion, steroid, hypoglossal nerve palsy, mononeuritis multiplex, covid-19 vaccination

Introduction

Mononeuritis multiplex is a rare form of cerebral nerve palsy caused by various factors, as the etiologies, infection, and autoimmunity are common. Herpes zoster and simplex are the predominant infections in the category of infection [1,2]. Among autoimmune causes, small-to-medium-sized vasculitis, such as an antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-related vasculitis and Sjogren’s syndrome, are common [1,2]. The progression of mononeuritis multiplex symptoms varies depending on the human body's etiology and immunological reactions [3,4]. Severe cases may involve multi-extremity paralysis, which should be treated with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, steroids, and plasma exchange, according to the etiology [2,5]. Thus, effective treatment requires the detection of etiology and rapid treatment.

COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccinations are also potential etiologies of mononeuritis multiplex, which can affect various nerves. Based on previous reports, post-COVID-19 and vaccination-related neurological impairments involve cranial nerves such as the facial, trigeminal, and vagus nerves [6-8]. However, there are few reports of mononeuritis multiplex following COVID-19 vaccination. Here, we report a case of mononeuritis multiplex that spread from the right hypoglossal nerve to the right hand and leg. The progression was acute, and the patient required treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin and steroid pulse therapy. Various complications occurred during the clinical course, and the treatment course was complicated. Our case demonstrates the importance of a clinical diagnosis of mononeuritis multiplex with prompt treatment and approaches to reduce long-term complications.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a chief complaint of dysphasia and difficulty speaking. Ten days before admission, the patient had received the third vaccination for COVID-19. He had a fever of >38 °C one day after vaccination. Seven days before admission, he experienced tingling on the right side of his tongue, followed by dysphagia and difficulty speaking. These symptoms progressed, and the patient noticed that the right side of his tongue had shrunk; therefore, he visited our hospital. He had a past medical history of varicella-zoster virus infection in the first branch of the left trigeminal nerve and had been treated with valaciclovir. The patient did not take any regular medication.

His vital signs at admission were as follows: blood pressure, 114/59 mmHg; pulse rate, 78 beats/min; body temperature, 36.9 °C, respiratory rate, 15 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 97% on room air. He was alert to time and place. Physical examination showed that the right half of his tongue was atrophied and shifted to the right during the prostration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Right sublingual neurological paralysis.

No other abnormal neurological findings were noted. There were no obvious abnormalities in the chest or abdomen and no skin eruptions. Physical examination revealed right hypoglossal nerve palsy; thus, viral infection, brain stroke, brain tumor, meningitis, ANCA-related vasculitis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome was suspected. Blood tests, head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), head computed tomography (CT), and lumbar puncture were performed. The results were within normal limits (Table 1).

Table 1. Initial laboratory data of the patient.

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; CK: creatine kinase; CRP: C-reactive protein

| Marker | Level | Reference |

| White blood cells | 6.8 | 3.5–9.1 × 103/μL |

| Neutrophils | 51 | 44.0–72.0% |

| Lymphocytes | 32.9 | 18.0–59.0% |

| Monocytes | 8 | 0.0–12.0% |

| Eosinophils | 6.9 | 0.0–10.0% |

| Basophils | 1.2 | 0.0–3.0% |

| Red blood cells | 5.34 | 3.76–5.50 × 106/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 16 | 11.3–15.2 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 47.8 | 33.4–44.9% |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 89.5 | 79.0–100.0 fl |

| Platelets | 24.6 | 13.0–36.9 × 104/μL |

| Total protein | 6.9 | 6.5–8.3 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.4 | 3.8–5.3 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 18 | 8–38 IU/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 27 | 4–43 IU/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 80 | 106–322 U/L |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase | 50 | <48 IU/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 165 | 121–245 U/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 13.9 | 8–20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.66 | 0.40–1.10 mg/dL |

| eGFR | ≥90 | > 60.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Serum Na | 137 | 135–150 mEq/L |

| Serum K | 3.9 | 3.5–5.3 mEq/L |

| Serum Cl | 101 | 98–110 mEq/L |

| Serum P | 3.1 | 2.7–4.6 mg/dL |

| Serum Mg | 2 | 1.8–2.3 mg/dL |

| CK | 112 | 56–244 U/L |

| CRP | 0.07 | <0.30 mg/dL |

| Artery blood gas analysis | ||

| pH | 7.418 | 7.35–7.45 |

| PCO2 | 42.5 | 35.0–45.0 mmHg |

| PO2 | 89.3 | 75.0–100.0 mmHg |

| HCO3 | 26.9 | 20.0–26.0 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 1.2 | 0.5–1.6 mmol/L |

| Cerebrospinal fluid testing | ||

| Color | clear | |

| Cell count | 1 | 0–5 /μL |

| Protein | 36 | 15–45 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 57 | 48–83 mg/dL |

| Chloride | 126.5 | 113–128 mEq/L |

A videoendoscopic examination of swallowing was performed to evaluate dysphagia, with no obvious problems associated with swallowing function. Since the difficulty in moving the tongue and the white coating was remarkable, the patient was referred to a dental and oral surgeon to rule out tongue cancer.

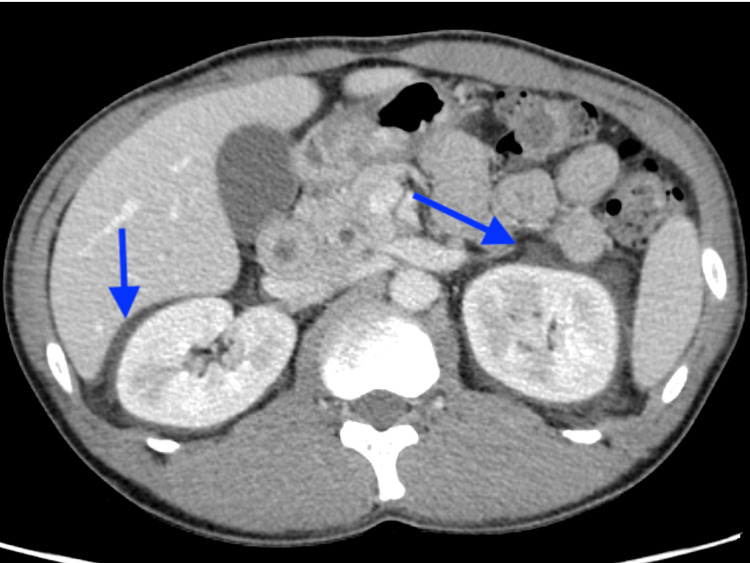

Because the patient had a history of herpes zoster, we also considered viral reactivation and prescribed acyclovir (1500 mg/day) and prednisolone (60 mg/day) from the second day of admission. However, lumbar pain and headache appeared on day four of admission, for which epidural hematoma after lumbar puncture was suspected. Plain lumbar magnetic MRI and head CT showed edematous findings around both kidneys, clinically suggesting the possibility of acute kidney injury due to acyclovir. As the patient tested negative for varicella virus, acyclovir was discontinued (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Edematous findings around both kidneys (blue arrows).

On the seventh day of illness, weakness of the right upper and lower extremities and a Romberg's sign was observed. Plain MRI of the upper arm and nerve conduction velocity tests were performed to investigate the cause, with no positive findings. Blood tests were negative for syphilis, hepatitis, HIV, ANCA, antinuclear antibody, and IgG4. Therefore, a clinical diagnosis of mononeuritis multiplex after administering the COVID-19 vaccine was made. On day seven of admission, prednisolone (60 mg/day), intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg/day for five days), and methylprednisolone (1 g/day for three days) were initiated after consultation with a neurology physician. On day nine of admission, muscle pain, and general malaise developed immediately after intravenous methylprednisolone administration. As intravenous methylprednisolone could be the cause, the administration was discontinued, and oral prednisolone (60 mg/day) was started. Subsequently, a tingling pain appeared on the right scalp. He was treated with valacyclovir (3 g/day for one week). Dysphagia and extremity weakness gradually improved after rehabilitation. On day 14, after admission, the patient was transferred to a university hospital for further investigation and advanced rehabilitation.

Discussion

This case showed the possibility of hypoglossal nerve palsy as a rare complication of COVID-19 vaccination, specific neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination, and the rapid treatment of mononeuritis multiplex to prevent symptom progression.

The relationship between the COVID-19 vaccine and mononeuritis multiplex has been discussed in various studies. Several case reports have shown an increased risk of mononeuritis multiplex within a few days to months after COVID-19 vaccination [8,9]. A review of COVID-19 vaccination also showed that most symptoms related to mononeuritis multiplex were mild and disappeared naturally [10]. However, some cases show severe symptoms that affect the patient’s activities of daily life and require intensive treatment [7,11]. Our patient initially had mild symptoms and did not require treatment for his vital symptoms. However, within one week, the symptoms progressed drastically from the tongue to the extremities, causing difficulties in walking. The clinical course of mononeuritis multiplex varies, and some cases caused by vasculitis from autoimmune and infectious diseases may be progressive [5,12]. Precise follow-up and prompt treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins and steroids should be initiated to prevent disease progression.

Hypoglossal nerve palsy could be a rare symptom following COVID-19 vaccination and warrants further investigation in future studies. Among the complications of COVID-19 vaccination, various neurological complications were reported in 2020 [9,10]. Guillain-Barre syndrome is a well-known but rare complication of COVID-19 vaccination and appears a few weeks after vaccination [13]. Other cranial nerves may also be involved in the complications of COVID-19. Several case reports and reviews have reported facial palsy, the pain of the trigeminal and facial nerves, and diplopia of the oculomotor nerves [10,14]. However, hypoglossal nerve palsy is rare, and its pathophysiology remains unclear. In the present case, the initial finding was difficulty in tongue movement caused by palsy of the hypoglossal nerves, which led to systemic neurological symptoms. Clinicians should consider assessing single cranial symptoms following COVID-19 because of the possible spread of multiple nerve symptoms, causing a decreased quality of life.

The COVID-19 pandemic may persist in the future; therefore, preventable measures are vital. Vaccination is a critical measure for prevention. Although various complications have been reported, they are rare; therefore, vaccination should be promoted [15,16]. However, the possible symptoms following COVID-19 vaccination should be appropriately described, and help-seeking behaviors (HSB) to medical facilities should be facilitated, especially in rural contexts lacking healthcare resources [17-19]. The patient in the present case was younger, but the duration of his visit to the hospital was nearly two weeks. Early treatment could have prevented symptom progression [14]. When the same symptoms occur in older patients, HSB varies and is challenging, causing a greater delay in treatment. Citizens and healthcare professionals should be educated regarding responses to symptoms following vaccination, and information provision should be promoted [20].

Conclusions

Hypoglossal nerve palsy may be a symptom of COVID-19 vaccination. The symptoms vary and may progress without treatment. Physicians should consider the possibility of mononeuritis multiplex after COVID-19 vaccination and provide prompt treatment for acute symptom progression.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Early detection of mononeuritis multiplex & diagnosis of systemic diseases thru electrophysiological work out with polyneuropathy as preceeding symptom. Mutluay B, Koksal A, Karagoz N, et al. J Neurol Sci. 2015;357:341. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasculitic mononeuritis multiplex may be misdiagnosed as carpal tunnel syndrome. Ghazaei F, Sabet R, Raissi GR. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:0–7. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mononeuritis multiplex as the first presentation of refractory sarcoidosis responsive to etanercept. Marques IB, Giovannoni G, Marta M. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:237. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severe mononeuritis multiplex due to rheumatoid vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis in sustained clinical remission for decades. Tanemoto M, Hisahara S, Hirose B, et al. Intern Med. 2020;59:705–710. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3866-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Autoimmune vasculitis causing acute bilateral lower limb paralysis. Tokonami A, Ohta R, Katagiri N, Yoshioka N, Yamane F, Sano C. Cureus. 2022;14:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mononeuritis multiplex associated with SARS-CoV2-COVID-19 infection: case report. Enrique E-R, Javier B, Hernando R, Herney Andrés G. Int J Neurol Neurother. 2020;7:102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mononeuritis multiplex: an unexpectedly frequent feature of severe COVID-19. Needham E, Newcombe V, Michell A, et al. J Neurol. 2021;268:2685–2689. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peripheral nervous system manifestations associated with COVID-19. Andalib S, Biller J, Di Napoli M, et al. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21:9. doi: 10.1007/s11910-021-01102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVID-19 and the peripheral nervous system. A 2-year review from the pandemic to the vaccine era. Taga A, Lauria G. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2022;27:4–30. doi: 10.1111/jns.12482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.COVID-19 associated cranial nerve neuropathy: A systematic review. Finsterer J, Scorza FA, Scorza C, Fiorini A. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2022;22:39–45. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2021.6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peripheral neuropathy evaluations of patients With prolonged long COVID. Oaklander AL, Mills AJ, Kelley M, Toran LS, Smith B, Dalakas MC, Nath A. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9 doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mononeuritis multiplex as a rare and severe neurological complication of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a case report. Abdelhakim S, Klapholz JD, Roy B, Weiss SA, McGuone D, Corbin ZA. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:81. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Late onset of Guillain-Barré syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection: part of 'long COVID-19 syndrome'? Raahimi MM, Kane A, Moore CE, Alareed AW. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Hasan I, Saif-Ur-Rahman KM, Hayat S, et al. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2020;25:335–343. doi: 10.1111/jns.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Machida M, Nakamura I, Kojima T, et al. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.An updated review of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the importance of effective vaccination programs in pandemic times. García-Montero C, Fraile-Martínez O, Bravo C, et al. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Help-seeking behaviour: a concept analysis. Cornally N, McCarthy G. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17:280–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Older people's help-seeking behaviors in rural contexts: A systematic review. Ohta R, Ryu Y, Sano C. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.How people decide to seek health care: a qualitative study. Shaw C, Brittain K, Tansey R, Williams K. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1516–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Educational intervention to improve citizen’s healthcare participation perception in rural Japanese communities: A pilot study. Ohta R, Ryu Y, Kitayuguchi J, Sano C, Könings KD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]