Abstract

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are localized in the alveoli and alveolar ducts of the lung and are the only macrophages living in an aerobic environment. Recent studies have demonstrated that AMs play a central role in lung diseases, such as pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. It has become important to find a simple, effective way to eliminate AMs in order to investigate the function of AMs in vivo. 2-Chloroadenosine (2-CA), a purine analog, is reported to be selectively cytotoxic to cultured macrophages, and we hypothesized that it would deplete the number of AMs in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of mice without any effect on neutrophil or lymphocyte counts. After mice had inhaled 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h, AMs were found to be significantly depleted at 0 h [(4.42 ± 0.16) × 104/ml], 24 h [(4.17 ± 0.89) × 104/ml], 48 h [(3.17 ± 0.21) × 104/ml], and 72 h [(5.00 ± 0.64) × 104/ml] compared with concentrations in untreated controls [(12.1 ± 0.21) × 104/ml]. Neutrophil and lymphocyte counts in BALF did not change and histological changes in the lung were not observed after 2-CA treatment. The lung wet-to-dry weight ratio did not change at 0, 24, and 48 h after 2-CA aerosol application. The 2-CA aerosol had no effect on lung vascular permeability, as assessed by the intravenous administration of Evans blue, or on other phagocytes, as assessed by Kupffer cell counts. Our study demonstrates the efficacy of 2-CA in reducing AM numbers in vivo.

Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are found in the alveoli and alveolar ducts of the lung and are the only macrophages living in an aerobic environment. Recent studies have demonstrated that AMs not only act as phagocytes but also function as potent secretory cells (11, 15). To examine the role of AMs in various lung diseases, the elimination of AMs in vivo is required. Several researchers have demonstrated that the intratracheal administration or aerosolization of liposomes containing dichloromethylene diphosphonate can effectively reduce AM populations (4, 16, 17). Recently, 2-chloroadenosine (2-CA) was reported to exhibit a selective lethal effect on cultured macrophages (12). We hypothesized that the ingestion of 2-CA in aerosolized form would also deplete the AM population in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) without any effect on neutrophils and lymphocytes. We report here on the selective depletion of AMs in mice treated with aerosolized 2-CA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice (5- to 6-week-old males; Japan SLC Co., Kyoto, Japan) were used in all experiments. All mice were housed in the animal care facility at the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan, until the end of the experiments.

AM depletion.

To determine optimal 2-CA treatment conditions, mice (six per group) were exposed to various concentrations of 2-CA for various periods of time. 2-CA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 1 or 10 mM. Via a nose-only aerosol chamber, mice in one group received either aerosolized 2-CA at a concentration of 1 mM for 1, 2, or 3 h or saline for 2 h with an ultrasonic nebulizer (NE-U11B; Omron Co., Kyoto, Japan), driven at a rate of 0.75 ml/min. Mice in a second group were treated either with 1 or 10 mM 2-CA or with saline for 2 h. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed 24 or 48 h after treatment. In mice treated with 1 mM 2-CA for 2 h, BAL was performed 0, 24, 48, or 72 h after 2-CA treatment. BAL was also performed in six untreated control mice.

BAL.

A lavage was performed on each mouse to obtain intra-alveolar cells. Mice were each anesthetized intraperitoneally with approximately 2.0 mg of pentobarbital. The trachea of each mouse was exposed and was intubated with a 27-gauge needle. BAL was performed three times by the administration of 0.5 ml of sterile saline, and cells in the BALF were counted. For differential counts, the BALF was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 3 min, and the collected cells were stained with Giemsa stain for cytological examination.

Light microscopy.

Light microscopy was performed to determine whether the 2-CA aerosol affected the structure of the lungs. One mouse was killed by exsanguination 24 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h. An entire lung was removed, formalin fixed, and paraffin embedded, and slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin were prepared.

Pulmonary fluid measurement.

Both lungs from each of six mice were removed 0, 24, 48, or 72 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h, weighed, and dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 24 h (8). The lung wet-to-dry (W/D) weight ratio was determined to assess the severity of pulmonary edema.

Assessment of lung vascular permeability.

Evans blue (T-1824) in serum or plasma binds to the albumin fraction when T-1824 is present in low concentrations, and T-1824 has been used as a vascular protein tracer (1, 9, 13). It has been reported that 1 mol of albumin can bind a maximum of 8 to 14 mol of T-1824. To evaluate lung vascular permeability in control mice (n = 6) and in experimental mice (n = 6) immediately after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h, we measured the concentration of T-1824 (Nakalai Tesque Co., Kyoto, Japan) in BALF 30 min after the intravenous administration of T-1824 (20 mg/kg of body weight) dissolved in saline at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. Concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically (at 615 nm). The BALF/serum ratios of T-1824 were assessed.

Effect on other phagocytes.

To evaluate the influence of 2-CA aerosolization on phagocytes other than AMs, we examined the effect of 2-CA aerosolization on Kupffer cells, which represent a large portion of phagocytes (80%). Mice (n = 6) were killed by exsanguination 0, 24, or 48 h after treatment with 1 mM 2-CA for 2 h. The livers were removed, embedded in OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, Ind.), frozen in liquid nitrogen, cut in 5-μm sections on a cryostat, and fixed in acetone for 10 min. After blocking nonspecific binding sites with bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.), we performed an immunohistochemical analysis using anti-mouse macrophage monoclonal antibody F4/80 (BMA Biomedicals, Switzerland). The secondary antibody was the anti-rat immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase-linked F(ab′)2 fragment (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). After visualization with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine, tissue sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Three randomly selected fields per slide were read at a ×200 magnification with a light microscope, and antibody-positive cells containing nuclei were counted. Fields containing large vessels or bronchi were excluded.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± standard errors and were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance. The differences between groups were compared by Fisher’s PLSD test. Significance was determined at a P value of ≤0.05.

RESULTS

AM depletion.

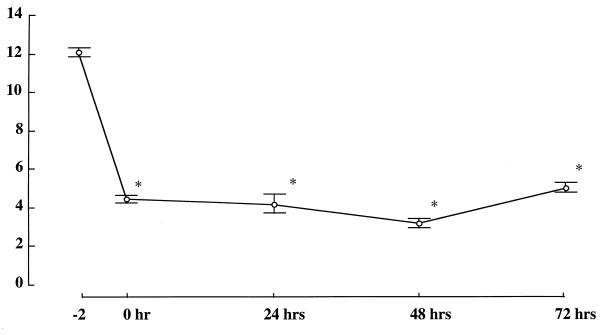

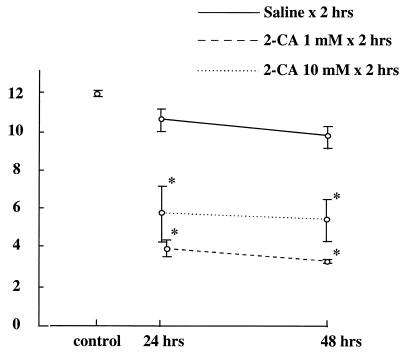

Changes in the numbers of AMs in the BALF after treatment with aerosolized 2-CA are shown in Fig. 1 to 3. After treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 1 h, AMs were found to be depleted at 24 h [(8.46 ± 0.26) × 104/ml] and at 48 h [(4.83 ± 1.11) × 104/ml]. After 2-CA treatment for 2 h, AMs were found to be significantly depleted at 24 h [(4.17 ± 0.89) × 104/ml] and at 48 h [(3.17 = 0.21) × 104/ml]. After 2-CA treatment for 3 h, AMs were found to be significantly depleted at 24 h [(5.42 ± 0.74) × 104/ml] and at 48 h [(6.00 ± 0.97) × 104/ml] compared with AMs from untreated controls [(12.1 ± 0.21) × 104/ml] (Fig. 1). There was no statistical difference in AM counts between treatments with 1 and 10 mM 2-CA (Fig. 2). After treatment with aerosolized saline, no significant change in the AM count was observed. When mice were treated with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h, the number of AMs in BALF decreased to ≤30% of the control number soon after 2-CA administration and remained low for at least 72 h after treatment (Fig. 3). BALF obtained immediately after 2-CA administration contained many dead macrophages, as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

FIG. 1.

AM count (104 per milliliter) in BALF 24 and 48 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 1, 2, or 3 h or with saline for 2 h. The control value was derived from untreated mice. *, P ≤ 0.01 versus control; **, P ≤ 0.05.

FIG. 3.

AM count (104 per milliliter) in BALF 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h. n = 6 for each time point. The value at −2 h was derived from untreated mice. *, P ≤ 0.01 versus control.

FIG. 2.

AM count (104 per milliliter) in BALF 24 and 48 h after treatment with 1 or 10 mM aerosolized 2-CA or with saline for 2 h. The control value was derived from untreated mice. *, P ≤ 0.01 versus control.

Neutrophil and lymphocyte counts in BALF after 2-CA treatment.

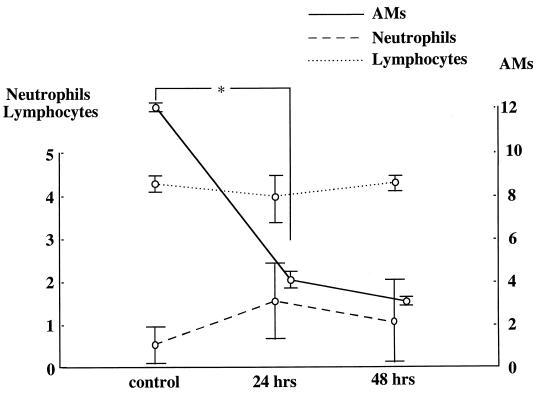

Changes in the numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes in BALF after treatment with 1 mM 2-CA are shown in Fig. 4. Although a specific reduction in the AM counts was observed, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts in BALF were not changed 24 and 48 h after application of 2-CA compared with counts in untreated controls.

FIG. 4.

Neutrophil and lymphocyte counts (102 per milliliter) and AM counts (104 per milliliter) in BALF 24 and 48 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h. The control value was derived from untreated mice. *, P ≤ 0.01 versus control.

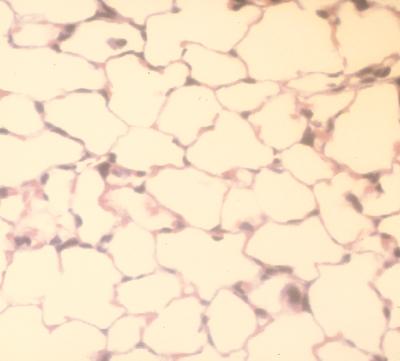

Light microscopy.

Light microscopy after treatment with aerosolized 2-CA showed normal lung morphology and no infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes into the lung tissue (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Lung section 24 h after treatment with 1 mM 2-CA aerosol for 2 h.

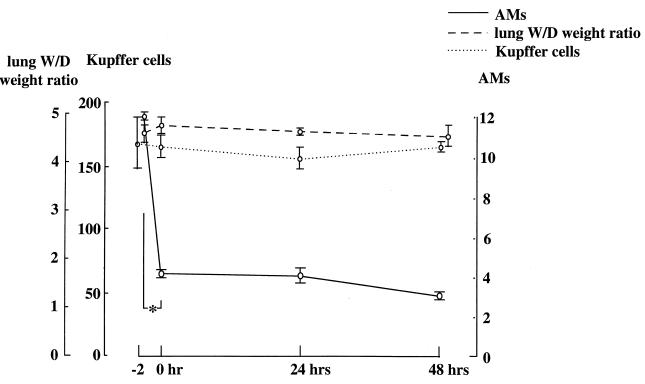

Lung W/D weight ratio after 2-CA treatment.

Changes in lung W/D weight ratio after treatment with aerosolized 2-CA are shown in Fig. 6. Although a specific reduction in AM counts was observed, the W/D weight ratios remained the same 0, 24, and 48 h after administration of aerosolized 2-CA.

FIG. 6.

Time course of lung W/D weight ratios and Kupffer cell counts (cells per square millimeter) 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h. The value at −2 h was derived from untreated mice. *, P ≤ 0.01 versus control. AM counts are reported as 104 per milliliter.

Assessment of lung vascular permeability.

To assess the effect of 2-CA on lung vascular permeability, the concentrations of T-1824 in serum and BALF were measured 30 min after intravenous administration of T-1824. T-1824 was injected immediately after 2-CA treatment. No statistical differences in BALF/serum ratios of T-1824 were observed between control mice (0.027 ± 0.005) and mice treated with 2-CA (0.029 ± 0.003).

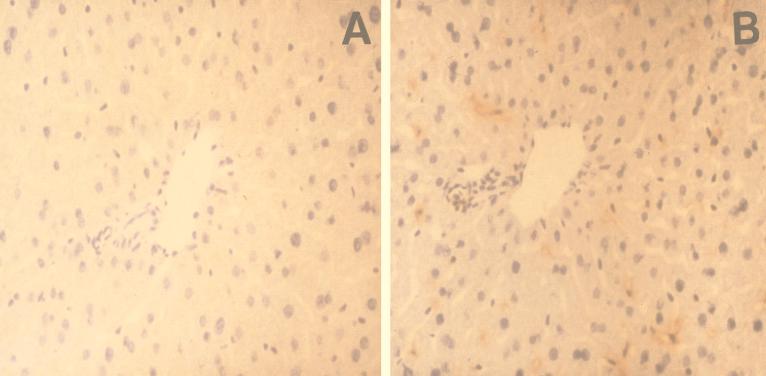

Effect on Kupffer cell counts.

Immunohistochemical staining of liver sections with anti-mouse macrophage monoclonal antibody F4/80 was performed. As shown in Fig. 7, only Kupffer cells stained positively. No statistically significant changes in Kupffer cell counts per square millimeter after 2-CA treatment were observed (Fig. 6).

FIG. 7.

(A) Liver section incubated with purified immunoglobulin G from control serum; (B) immunohistochemical staining of liver with anti-mouse macrophage monoclonal antibody F4/80.

DISCUSSION

AMs are the only macrophages found at the air-tissue interface of the lung and are the first cells to encounter inhaled antigens. Thus, AMs have a critical role as phagocytes. Recent studies have also demonstrated that AMs function as secretory cells and play an important role in regulating inflammatory reactions within the lungs (10, 15). For example, AMs are reported to play a protective role in Pseudomonas infections by promoting the initial recruitment of neutrophils into infected lungs (10). However, Broug-Holub et al. (7) demonstrated that in murine Klebsiella pneumonia, the elimination of AMs promotes neutrophil recruitment but decreases bacterial clearance and survival Brigham and Meyrick (6) reported that AMs were involved in the pathogenesis of endotoxin-induced lung injury. To evaluate the role of AMs in various lung diseases, researchers have depleted AMs in animals in vivo by the administration of silica (2) and carrageenan (3), which are selectively taken up by macrophages and react rapidly with the membranes surrounding secondary lysosomes. However, the reduction in AMs was not sufficient, and systemic responses often occurred. Other investigators have succeeded in selectively depleting a large fraction of AMs by administering clodronate intratracheally (4). Because AMs do not ingest clodronate when it is administered alone, a complicated procedure must be used to encapsulate clodronate within liposomes. Recently, it was reported that 2-CA, a purine analog, is selectively cytotoxic to cultured macrophages (12, 14). The mechanism of the inhibitory action of 2-CA remains unclear, but previous studies have demonstrated that the competitive reduction of intracellular adenosine content by 2-CA may reduce the viability of macrophages.

In this study, we depleted AMs in vivo by treatment with aerosolized 2-CA. Treatment with 1 mM aerosolized 2-CA for 2 h reduced the number of AMs in BALF to ≤30% of control values, and the number remained low at least 72 h after 2-CA administration. We demonstrated that the capacity of 2-CA to deplete AMs is comparable to that of clodronate. 2-CA aerosol is supposed to be easier to administer than clodronate. However, it is unclear why the depletion was only 70%. Several investigators have separated AMs into different subpopulations and have demonstrated that each subpopulation responds differently to different stimuli. We assume that the heterogeneity of AMs is one reason for the lower level of depletion we observed. Several studies demonstrated that intratracheal administration of drugs may induce neutrophil chemotaxis in the lung (4, 16, 17). However, in our study, the administration of aerosolized 2-CA did not affect leukocyte and lymphocyte counts in BALF, and we detected no mucosal edema or cellular infiltration in lung tissue microscopically. The 2-CA aerosol did not appear to stimulate the direct recruitment of new macrophages to the lung. Moreover, treatment with 2-CA aerosol did not affect the lung W/D weight ratio, and 2-CA did not promote lung vascular permeability as assessed by the concentration of T-1824 in BALF. These findings demonstrate that 2-CA does not cause lung edema. 2-CA treatment did not influence Kupffer cell counts, which indicates that 2-CA does not affect the viability of other phagocytes. We did not examine the effect of 2-CA on interstitial macrophages. Interstitial lung macrophages are thought to be immediate precursors of AMs and to function similarly. However, Bowden and Adamson (5) reported that the number of interstitial lung macrophages is one-sixth to one-fifth that of AMs. We assume that the effect of 2-CA on interstitial lung macrophages is not significant. It is not possible to know the precise concentration of the drug within the lungs when it is administered by aerosolization; however, individual differences in drug concentrations in these experiments were small. This may be the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of 2-CA for depleting AM numbers in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kenichi Nishioji and Takeshi Okanoue of the Third Department of Medicine, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, for providing anti-mouse macrophage monoclonal antibody F4/80.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen T H, Ochoa M, Jr, Roth R F, Gregersen M I. Special absorption of T-1824 in plasma of various species and recovery of the dye by extraction. Am J Physiol. 1953;175:243–246. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.175.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison A C, Harington S L, Bribech M. An examination of cytotoxic effects of silica on macrophages. J Exp Med. 1976;124:141. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascheim L, Raffle S. The immunodepressive effect of carrageenan. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1972;11:253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg J T, Lee S T, Thepen T, Lee C Y, Tsan M F. Depletion of alveolar macrophages by liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2812–2819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowden D H, Adamson I Y R. The pulmonary interstitial cell as immediate precursor of the alveolar macrophage. Am J Pathol. 1972;68:521–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brigham K L, Meyrick B. Endotoxin and lung injury. Am J Respir Dis. 1986;133:913–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broug-Holub E, Toews G B, Van Iwaarden J F, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L, Paine III R, Standiford T J. Alveolar macrophages are required for protective pulmonary defenses in murine Klebsiella pneumonia: elimination of alveolar macrophages increases neutrophil recruitment but decreases bacterial clearance and survival. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1139–1146. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1139-1146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins J A, Braitberg A, Butcher H R. Changes in lung and body weight and lung water content in rats treated for hemorrhage with various fluids. Surgery. 1973;73:401–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregersen M I, Gibson J J, Stead E A. Plasma volume determination with dyes: errors in colorimetry; use of the blue dye T-1824. Am J Physiol. 1935;113:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto S, Pittet J, Hong K, Folkesson H, Bagby G, Kobzik L, Frevert C, Watanabe K, Tsurufuji S, Wiener-Kronish J. Depletion of alveolar macrophages decreases neutrophil chemotaxis to Pseudomonas airspace infections. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:819–828. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan C F. Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Investig. 1987;79:319–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI112815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohtani A, Kumazawa Y, Fujisawa H, Nishimura C. Inhibition of macrophage function by 2-chloroadenosine. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1982;32:189–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rawson R A. The binding of T-1824 and structurally related diazo dyes by the plasma protein. Am J Physiol. 1943;113:708–717. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T, Yamaguchi J. 2-Chloroadenosine and macrophages. Proc Jpn Soc Immunol. 1980;213:10. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibille Y, Reynolds H Y. Macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils in lung defense and injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:471–501. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thepen T, Van Rooijen N, Kraal G. Alveolar macrophage elimination in vivo is associated with an increase in pulmonary immune response in mice. J Exp Med. 1989;170:499–509. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage “suicide” technique. J Immunol Methods. 1989;124:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]