Abstract

Three unique 5,6-seco-hexahydrodibenzopyrans (seco-HHDBP) machaeridiols A–C, reported previously from Machaerium Pers., have displayed potent activities against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, and E. faecalis (VRE). In order to enrich the pipeline of natural product-derived antimicrobial compounds, a series of novel machaeridiol-based analogs (1–17) were prepared by coupling stemofuran, pinosylvin, and resveratrol legends with monoterpene units R-(−)-α-phellandrene, (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol, and geraniol, and their inhibitory activities were profiled against MRSA ATCC 1708, VRE ATCC 700221, and cancer signaling pathways. Compounds 5 and 11 showed strong in vitro activities with MIC values of 2.5 μg/mL and 1.25 μg/mL against MRSA, respectively, and 2.50 μg/mL against VRE, while geranyl analog 14 was found to be moderately active (MIC 5 μg/mL). The reduction of the double bonds of the monoterpene unit of compound 5 resulted in 17, which had the same antibacterial potency (MIC 1.25 μg/mL and 2.50 μg/mL) as its parent, 5. Furthermore, a combination study between seco-HHDBP 17 and HHDBP machaeriol C displayed a synergistic effect with a fractional inhibitory concentrations (FIC) value of 0.5 against MRSA, showing a four-fold decrease in the MIC values of both 17 and machaeriol C, while no such effect was observed between vancomycin and 17. Compounds 11 and 17 were further tested in vivo against nosocomial MRSA at a single intranasal dose of 30 mg/kg in a murine model, and both compounds were not efficacious under these conditions. Finally, compounds 1–17 were profiled against a panel of luciferase genes that assessed the activity of complex cancer-related signaling pathways (i.e., transcription factors) using T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells. Among the compounds tested, the geranyl-substituted analog 14 exhibited strong inhibition against several signaling pathways, notably Smad, Myc, and Notch, with IC50 values of 2.17 μM, 1.86 μM, and 2.15 μM, respectively. In contrast, the anti-MRSA actives 5 and 17 were found to be inactive (IC50 > 20 μM) across the panel of these cancer-signaling pathways.

Keywords: machaeridiol analogs, synthesis, antibacterial, MRSA, VRE, in vivo nosocomial MRSA assay, anticancer, transcription factors

1. Introduction

There are currently considerable challenges with the treatment of infections caused by strains of clinically relevant bacteria that show multidrug-resistance (MDR), such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Enterococci faecalis (VRE), as well as the recently emerged and extremely drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis XDR-TB [1]. The continuous gradual decline in cases of MRSA and other MDRs since 2010 was accompanied by a sudden spike due to the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This spike represented a 34% increase in cases of MRSA, with some American states seeing an increase in cases as high as a 99% [2,3]. The national estimate for invasive MRSA incidence rates showed that one in three people carry S. aureus in their nose and two in 100 people carry MRSA [4]. Like MRSA, VRE infections are commonly acquired by hospitalized patients. Enterococcal infections can be lethal, particularly those caused by VRE. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP), the number of nosocomial VRE isolates increased in the United States by 20-fold between 1989 and 1993, and now such isolates are the second-to-third most common cause of nosocomial infections in the USA. Overall antibiotic resistance is on the rise, with some strains developing resistance to powerful antibiotics, such as vancomycin, that are typically used as a last resort when other efforts fail.

Because cancer patients are more likely to be infected and die from MRSA bloodstream infections (BSI), a comprehensive review was reported recently by Li et al. (2020) [5], who “estimated the global MRSA prevalence among bacteremia in patients with malignancy, and studied the predictors and mortality of cancer patients with MRSA bacteremia or BSI”. The authors observed that “the pooled prevalence of MRSA was 3% (95% CI 2–5%) among all BSIs and 44% (95% CI 32–57%) among S. aureus bacteremia in cancer patients” [5]. In addition, An et al. (2016) [6] found that “MRSA infection can enhance metastasis ability of A549 cell (lung cancer) and increase matrix metalloproteinase (MMP2 and MMP9) expressions in MRSA infected A549 cell, and concluded that MRSA infection can enhance NSCLC cell metastasis by up-regulating TLR4/MyD88 signaling”. Considering the urgency of newly emerging MRSA infection due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the BSI of cancer patients, novel antibacterial leads that focus on the dual effects of anti-MRSA and anticancer approaches from natural and synthetic sources are urgently warranted.

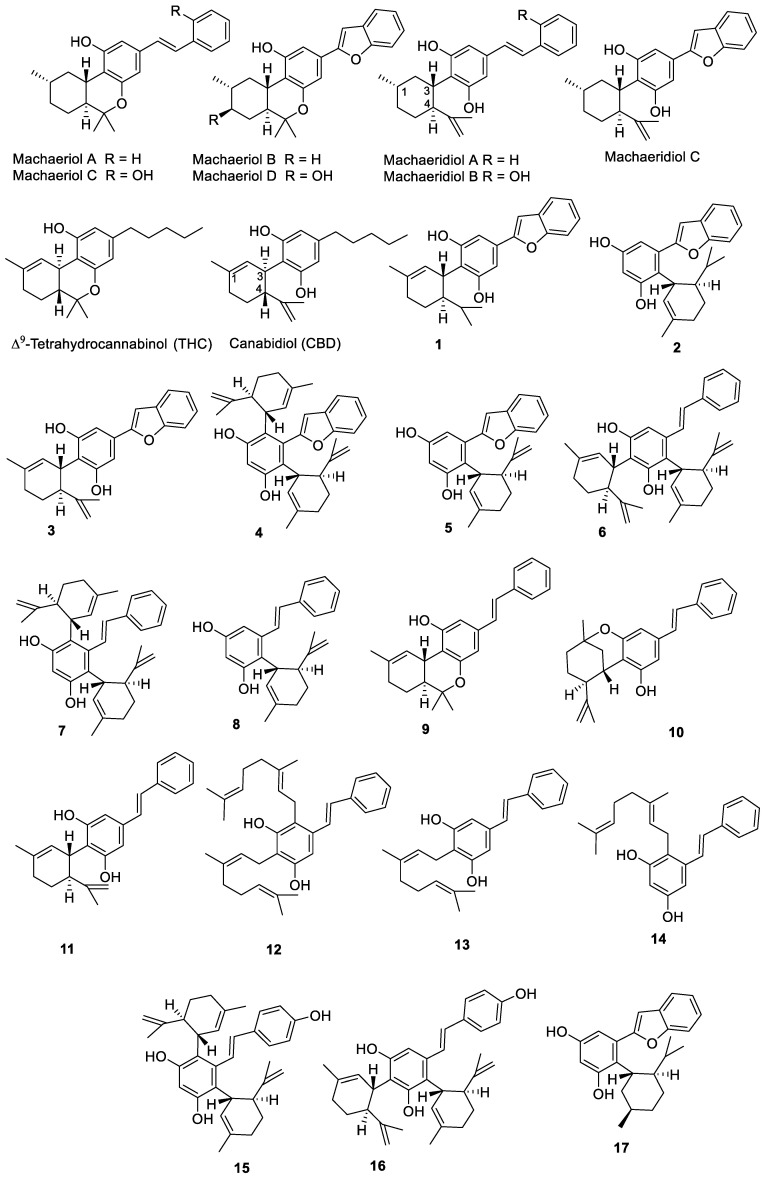

Based on our ongoing effort to uncover antimicrobial agents from natural products from higher plants, hexahydrodibenzopyran (HHDBP)-type phytocannabinoids showed promising activity against MRSA and VRE. The examples of these phytocannabinoids are machaeriols A–D and machaeridiols A–C (Figure 1), isolated from Machaerium Pers. (Rimachi 12161), which are very unique and rare in higher plants [7,8,9]. HHDBP occurs in chemotaxonomically unrelated sources, such as liverworts, which are non-vascular plants referred to as Marchantiophyta, and an aralkyl analogue of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), perrottetinen, was previously reported from the liverwort Radula perrottetii [10,11]. In addition, two Leguminoseae species, Desmodium canum and Sophora tetraptera, have yielded aralkyl phytocannabinoids [12,13]. However, we previously reported the significance of the chemistry of HHDBP or 5,6-seco-HHDBP (machaeriols and machaeridiols) and their antimicrobial activities, especially against MRSA, VRE, and Gram-negative bacteria [9]. Interestingly, the structural resemblance between machaeridiol and cannabidiol (CBD) (Figure 1) reflected their similarity in antimicrobial activities against MRSA, and machaeridiols A–C were found to be more potent than cannabidiol (CBD) and vancomycin [9,14].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of compounds isolated from Machaerium sp. and synthetic analogs.

In this paper, we report the synthesis of a series of new and diverse stemofuran-, pinosylvin-, and resveratol-type aralkyl compounds (1–11, 15–17) and geraniol-substituted pinosylvin analogs, such as cannabigerol (CBG) analogs (12–14), and profile their antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Compounds 5 and 11 showed potent activity against MRSA and VRE, while compound 14 exhibited moderate anti-MRSA activity with strong anticancer activity against a panel of transcription factors. The reduction of the double bonds of compound 5 yielded two diastereomers and the major diastereomer 17 showed no change in its antibacterial activity. The total synthesis and antibacterial activities of compounds 1–17 toward MRSA and VRE, as well as their anticancer activities against luciferase transporter genes, are reported in this paper.

2. Results

Seven phytocannabinoids with HHDBP and seco-HHDBP skeleta, machaeriols A–D and machaeridiols A–C, were previously isolated from Macherium Pers., of which the machaeriol chemotype possesses a unique pharmacophore with 10aS absolute configuration, an opposite configuration to 10aR of THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) / HHC (hexahydrocannabinol) [8]. In addition, the configuration of the machaeridiol chemotype at 1S, 3S, and 4S positions is opposite to those at 3R and 4R positions of CBD. Therefore, an unprecedented structural similarity for the HHDBP skeleton was observed between machaeriol and HHC, and for the 5,6-seco-HHDBP skeleton between machaeridiol and dihydro-CBD. Because machaeriols A–D are analogues to trans-HHC, they show an enantiomeric configuration at the ring junction, established by CD and enantioselective total syntheses [15,16,17]. Similarly, the macheridiol chemotype is similar to dihydro-CBD, with the n-alkyl mioety replaced by steryl and benzofuranyl forms. [18] The pseudo-enantiomeric configuration at C-3 and C-4, compared to CBD, was established by CD studies. Based on the uniqueness of the stereogenic ring junction of the machaeridiol chemotype, the synthesis of machaeridiol B was reported [19] to involve long steps; to repeat this method would be quite challenging.

2.1. Synthesis of Analogs 1–17

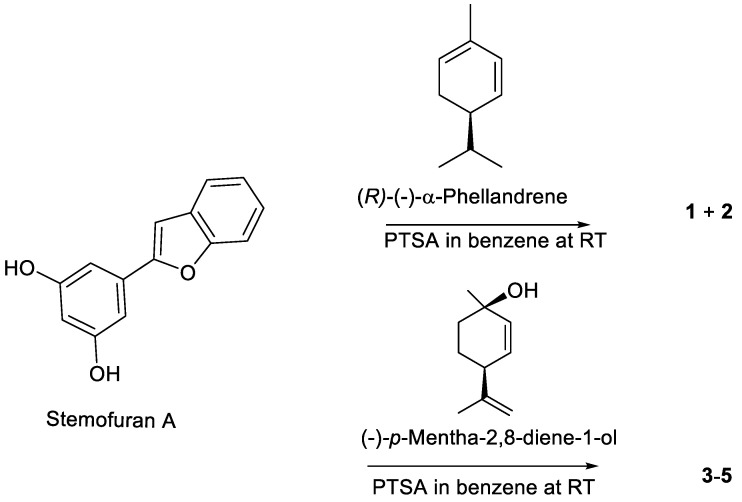

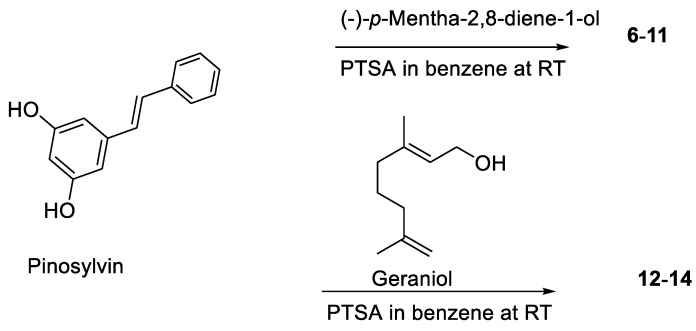

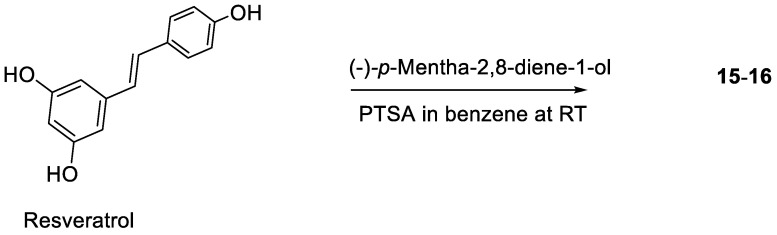

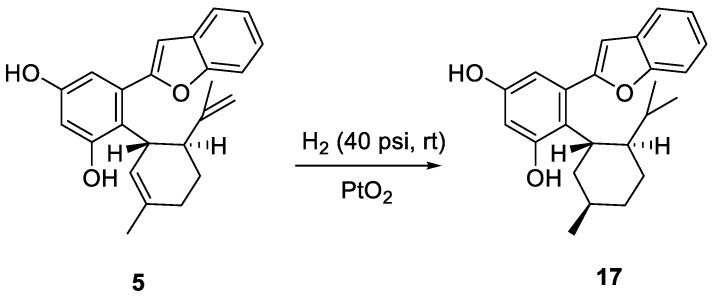

Based on 5,6-seco-HHDBP machaeridiols A and C (Figure 1), consisting of styryl and benzopyran legends, respectively, attached to cyclic monoterpenoid via a catechol unit [7,8,9], we introduced different monoterpene units, (R)-(−)-a-phellandrene, (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol [(1R,4S)-1-methyl-4-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-2-enol], geraniol with benzopyran (stemofuran A), pinosylvin, and resveratrol legends to form new trans-benzopyan, styryl and resveratrol analogs 1–17 (Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3 and Scheme 4). Catechol and monoterpens coupling reactions were carried out using the simple and efficient one-pot synthetic protocol described by Mascal et al. [20]. Stemofuran A was coupled with (R)-a-phellandrene and (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol (Scheme 1) to yield compoundss 1, 2, and 3–5, respectively. Similarly, pinosylvin was coupled with (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol and geraniol (Scheme 2) to yield compounds 6–11 and 12–14, respectively, and resveratrol was coupled with (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol (Scheme 3) to yield compounds 15–16. The structures of these compounds were confirmed by extensive 2D-NMR analysis and their configuration was determined by NOESY correlations. The complete hydrogenation of compound 5 with Adam’s catalyst yielded 17 and the absolute configuration at C-1 of 17 was determined by analyzing its NOESY data; it was assigned as 1R and named as 5-(benzofuran-2-yl)-4-(1R,2S,5R)-2-isopropyl-5-methylcyclohexyl)benzene-1,3-diol.

Scheme 1.

Coupling of stemofuran A with (R)-(−)-α-phellandrene and (−)-p-mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol.

Scheme 2.

Coupling of pinosylvin with (−)-p-mentha-2-8-diene-1-ol and geraniol.

Scheme 3.

Coupling of resveratrol with p-mentha-2-8-diene-1-ol.

Scheme 4.

Catalytic hydrogenation of compound 5.

2.2. Antimicrobial Activities against Gram-Positive Bacteria and Fungi

The antimicrobial activities of compounds 1–17 were evaluated against a panel of microorganisms, including MRSA, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, Enterococcus faecium (VRE), and Cryptococcus neoformans, together with anticancer activity against a panel of luciferase reporter genes of complex cancer-related signaling pathways. All compounds were initially subjected to in vitro antimicrobial primary screens to assess their IC50 values; compounds 4, 6, 9+10, 12, and 16 were found to be inactive (IC50 > 20 μg/mL) (Table 1). Analogs from the stemofuran A, pinosylvin, and resveratrol legends exhibited strong-to-modest IC50 values in the range of 0.91 μg/mL to 8.04 and 1.17 μg/mL to 3.38 μg/mL against MRSA and VRE, respectively. Representative analogs from each of these three legends, compounds 5, 11, 13, 14 and 17, were selected, based on IC50 values of 3.0 μg/mL or <3.0 μg/mL as a cut-off value against MRSA for MIC determination. Among the analogous of stemofuran A (1–5 and 17), pinosylvin (6–14), and resveratrol (15, 16), compound 5, 11, and 17 exhibited the most potent activity against MRSA ATCC 1708, with IC50/MIC values of 1.18/2.50 μg/mL, 0.91/1.25 μg/mL, and 0.95/1.25 μg/mL, respectively. In addition, these three analogs (5, 11, and 17) were found to be active against E. faecalus ATCC 700221 (VRE) with IC50/MIC of 2.27/2.50 μg/mL, 1.17/2.50 μg/mL, and 2.28/2.50 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, among the pinosylvin- geraniol analogs (12–14), compound 14 was found to be more active, compared to 12 and 13, against MRSA and VRE, with MIC of 5 μg/mL.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activities* of machaeridiol based synthetic analogs 1–3, 5, 7–11, 13–15, and 17.

| Compounds | IC50 / MIC (μg/mL) * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA ATCC 1708) | Vancomycin-Resistant E. faecium (VRE ATCC 700221) |

Cryptococcus neoformans (ATCC 90113) |

|

| 1 | 3.24/NT | 2.49/NT | NA |

| 2 | 3.69/NT | 18.37/NT | 16.74/NT |

| 3 | 8.15/NT | 3.38/NT | NA |

| 5 | 1.18/2.50 ** | 2.27/2.50 | 2.15/2.50 |

| 7 | 8.04/NT | NA | NA |

| 8 | 16.51/NT | 18.1/NT | NA |

| 11 | 0.95/1.25 | 2.28/2.50 | 0.95/2.50 |

| 13 | 2.3/10.0 | 3.2/10.0 | 4.3/NT |

| 14 | 3.0/5.0 | 2.3/5.0 | 1.5/NT |

| 15 | 17.0/NT | 17.8/NT | >20/NT |

| 17 | 0.91/1.25 | 1.17/2.50 | 1.92/5 |

| Machaeriol C # | 0.69/1.25 | 1.16/2.5 | NA |

| Machaeridiol A # | 1.03/2.5 | 0.72/2.5 | 15/NT |

| Machaeridiol C # | 0.38/1.25 | 0.72/1.25 | 25/NT |

| Methicillin | 2.2/50 | >20/20 | NT |

| Meropenem | 7.03/12.50 | NA | NA |

| Amphotericin B | NT | NT | 0.88/1.56 |

* The primary (IC50) and secondary (MIC) assays were run separately and each was executed in duplicate. ** Compounds 5, 11, 13, 14, and 17 were selected for MIC determination based on their IC50 cut-off values of 3.0 μg/mL or < 3.0 μg/mL against MRSA. Compounds 4, 6, 9+10, 12, and 16 were inactive in the primary assay (IC50 > 20 μg/mL). NA: not active. NT: not tested. All compounds were inactive against VERO cells. MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus, VRE: vancomycin-resistant Enterococci. # Literature values [7,8,9] are included for comparison with the synthetic analogs.

The activities of compounds 5, 11, and 17 were found to be similar to those of natural products machaeridiol C (i.e., a stemofuran A type, 17) and machaeridiol A (i.e., a pinosylvin type, 11), with MIC values of 1.25 μg/mL to 2.5 μg/mL, and more potent than the positive drug control meropenem against MRSA and VRE.

2.3. Antimicrobial Combination Studies

Based on our previous investigation on the synergistic activity between machaeridiol B and machaeriol C against MRSA [9], analogs 5 and 17 (i.e., machaeridiol type analogs) were subjected to combination studies with machaeriol C. Because both compounds 17 and machaeriol C showed potent activity against MRSA (Table 1 and Table 2), they were subjected to a broth microdilution checkerboard assay [9], using an MRSA strain. The presence of machaeriol C improved the anti-MRSA activity of 17; for example, 17 alone showed an MIC of 0.625 μg/mL, but in combination with machaeriol C, the MIC of 17 was decreased to 0.156 μg/mL. This combination study of 17 and machaeriol C displayed a synergistic effect with a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) value of 0.5 against MRSA, showing a four-fold decrease in MIC of 17 to 0.312 μg/mL (Table 2). On the other hand, compound 5 + machaeriol C displayed an additive effect with an FIC value of 0.75, showing a four-fold reduction of MIC for 5 from 1.25 μg/mL to 0.312 μg/mL and a two-fold reduction of MIC of macheriol C from 1.25 μg/mL to 0.625 μg/mL. However, a combination of either 5 or 17 with antibiotic vancomycin did not show any such effect against MRSA (Table 2). All checkerboard assays were run in triplicate.

Table 2.

Combination study of compound 5 and 17 with machaeriol C by checkerboard* assay against MRSA.

| Compound | MRSA (ATCC 1708) MIC (μg/mL) |

Concentration (μg/mL) |

Combination Effect MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.25 | 5 + MC @ 0.625 | MIC of 5 @ 0.312 (^4X) |

| Machaeriol C (MC) | 1.25 | MC + 5 @ 0.625 | MIC of MC @ 0.625 (^2X) (FIC 0.75) |

| 17 | 0.625 | 17 + MC @ 0.156 | MIC of 17 @ 0.156 (^4X) |

| 17 + MC @ 0.312 | MIC of 17 @ 0.312 (^2X) | ||

| Machaeriol C (MC) | 1.25 | MC + 17 @ 0.156 | MIC of MC @ 0.625 (^2X) |

| MC + 17 @ 0.312 | MIC of MC @ 0.312 (^4X) (FIC 0.50) | ||

| Ancomycin | 1.00 | - | - |

| - | - | 5 + Vancomyci | No effect (FIC > 1) |

| - | - | 17 + Vancomycin | No effect (FIC > 1) |

* Checkerboard assays of compound 5 and 17 were run separately at two different dates, each in triplicate. In addition, 17 was run two times (^2X: two-fold reduction in MIC; ^4X: four-fold reduction in MIC; FIC: fractional inhibitory concentrations).

2.4. In Vivo Antimicrobial Activity Studies agaisnt Nosocomial MRSA

Compounds 11 and 17 were evaluated in vivo against MRSA strain USA300, using a nosocomial assay protocol in a murine model. Both compounds were found to be unable to reduce bacterial loads in the nasopharynx and lung at a dose of 30 mg/kg, using ciprofloxacin as a reference standard. A single intranasal dose of compound, vehicle, or ciprofloxacin was administered 12 h following infection, and this regimen produced significant but modest results for ciprofloxacin (Table 3). Alternate concentrations, additional treatments, parental versus intranasal routes, and/or alternate treatment schedules need to be investigated to determine the optimal results for ciprofloxacin control, to better compare the efficacy of compounds 11 and 17.

Table 3.

Comparison of bacterial loads in lungs and nasopharyngeal washes after treatment with a commercially available antibiotic and compounds 11 and 17.

| Group ID (n-value) |

Bacterial Loads in Lung (log10 CFU/mL ± SD) |

Bacterial Loads in Nasopharyngeal Wash (log10 CFU/mL ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Control (4) | 6.191 ± 0.078 | 5.699 ± 0.585 |

| Ciprofloxacin * (4) | 5.304 ± 0.198 * | 4.648 ± 0.545 * |

| Compound 11 (5) | 6.053 ± 0.175 | 5.436 ± 0.517 |

| Compound 17 (5) | 5.902 ± 0.373 | 5.982 ± 0.254 |

* Bacterial loads were significantly lower in lungs and nasopharyngeal washes of mice treated with ciprofloxacin, compared with those treated with vehicle (p ≤ 0.039).

2.5. Activities against Cancer-Related Signaling Pathways

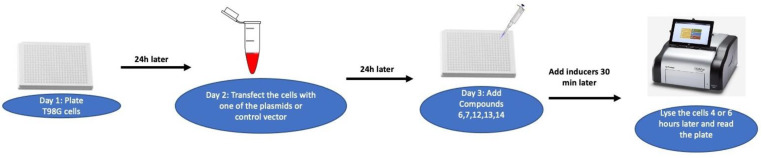

In order to evaluate the anticancer activities and understand the mechanism of action, compounds 1–17 were profiled against a panel of luciferase reporter genes that assessed the activity of complex cancer-related signaling transduction pathways, using T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells (i.e., transcription factors; TF; Scheme 5). The compounds were considered inactive if their inhibition was less than 40% of the induction at the highest concentration tested (20 µM). These inactive compounds were not further advanced for a dose response assay for IC50 determination. Among the compounds (Table 4), the geraniol derivative of pinosylvin legend 14 exhibited strong activity against many signaling pathways (TFs), notably with IC50 values between 1.86 µM to 4.45 µM against the Stat, Smad, Myc, Ap-1, NF-kB, E2F, ETS, and Notch pathways. However, the MRSA active stemofurans 5 and 17 and the pinosylvin 11 analogs were found to be inactive and weakly active, respectively, against the panel of these signaling pathways.

Scheme 5.

Schematic assay protocol of cancer-related signaling transduction pathways using T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells.

Table 4.

Activity* of compound 7, 8, 11, 13, and 14 against cancer-related signaling pathways in T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells.#

| Compounds | Stat3/IL-6 | Smad /TGF-beta | Ap-1/PMA | NF-kB/PMA | E2F/PMA | Myc/PMA | Ets/PMA | Notch/PMA | FoxO | Wnt/m-wnt 3a | Hdghog/PMA | miR-21 | pTK | Ras | AhR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 8.99 | 10.5 | - | - | < 5 | 7.55 | - | 12.6 | - | 2.5 | 5.3 | 18.9 | - | - | - |

| 8 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 10.25 | 7.66 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 7.3 | < 5 | - | 12.1 | 7.0 | - | - | 7.0 | 2.0 |

| 11 | 18.3 | 21 | 21 | 18.6 | 5.7 | 10.2 | > 20 | 10.59 | - | 15.9 | 13.79 | - | - | 13.78 | |

| 13 | 6.55 | 9.95 | 10.89 | 16.9 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 11.44 | < 5 | - | 7.44 | - | 11.87 | - | 11.13 | - |

| 14 | 4.33 | 2.17 | 4.45 | 4.8 | 4.43 | 1.86 | 4.7 | 2.12 | 13.7 | 9.11 | 8.35 | - | - | 6.5 | 7.4 |

* Values are IC50 in µM that inhibited luciferase induction by 50%. Test agents were added to cells 30 min before the addition of the indicated inducer and were harvested 4 or 6 h later for the luciferase assay (Notch, FoxO, Wnt, Hedgehog, miR-21). No inducer was added to cells transfected with the FoxO, miR-21, or pTK control vector.# This unique assay panel had a special feature of evaluating which pathways were sensitive (modulated) to a test agent. Each test agent was run at various concentrations and each concentration was tested in duplicate. As this multiplex assay offered many advantages for the simultaneous measurement and analysis of multiple pathways for any test agent, the intra- and inter-assay precision, accuracy, and reproducibility were high with this method. The results were normalized to the control vector, which was pTK. This empty vector control allowed us to see any non-specific cytotoxic effects of the test compounds on the cells. -: No activity detected.

3. Discussion

The synthesis of the compounds 1–17, using stemofuran A, pinosylvin, and resveratrol legends, was inspired by the potent anti-MRSA and anti-VRE activities of machaeridiol A and machaeridiol C [9], CBD [21], and CBG [22] to develop a new pipeline of anti-MRSA active compounds. This appears to be the first report of compounds 1, 2, 4–12, 14, 15, and 17 from either a natural or synthetic source. Compounds 3 and 16 were previously synthesized by coupling reactions similar to those described in the current study, but using a different catalyst (BF3·OEt2) [16] and a different solvent (DCM) [23], respectively. Compound 13 (amorphastibol) was reported from three Amorpha species [24]. Compounds 9 and 10 were isolated as a 5:1 mixture and very likely formed by an acid-catalyzed intermolecular cyclization of compound 11, as previously reported for CBD under similar conditions [25]. Compound analogs to 6–8 and 11, but without an exocyclic double bond in the monoterpene moiety, were reported from Lindera reflexa [26,27].

The HHDBP and 5,6-seco-HHDBPs, machaeriols and machaeridiols, were only reported from Machaerium Pers. (Rimachi 12161), despite our search for other Machaerium species available at the the repository of the National Center for Natural Products Research at the University of Mississippi. However, the stereo-specific total synthesis of machaeriols A–D and mechaeridiol B (Figure 1) has been reported [15,19,28]. In addition, several HHC-related machaeriol analogs were synthesized, showing a strong inhibition of tumor (breast cancer) growth by targeting VEGF-mediated angiogenesis signaling in endothelial cells and suppressing VEGF production and cancer cell growth [29]; however, to best of our knowledge, machaeridiol analogs have not been synthesized and reported for anti-MRSA or anticancer activities.

The antibacterial activities against MRSA and VRE, as well as anticancer activities toward signal transduction pathways, were assessed; compounds 5, 11, and 17 showed potent activities against MRSA and VRE, with MIC values in the range of 1.25 μg/mL to 2.50 μg/mL, while compound 14 exhibited moderate activity (MIC 5.0 μg/mL). It is intriguing to note that the combination of seco-HHDBP 17 with HHDBP machaeriol C displayed a synergistic effect against MRSA, showing a four-fold decrease in the MIC of both 17 and machaeriol C, while compound 5 showed an additive effect with machaeriol C and a four-fold decrease in the MIC of 5 (Table 2). The strong in vitro efficacy of compounds 11 and 17 against MRSA prompted investigation of their efficacy in vivo. A preliminary experiment employing a single intranasal dose of each compound, vehicle, and ciprofloxacin yielded modest efficacy results for ciprofloxacin only. Different parameters in the treatment regimen must be tested to fully determine whether compounds 11 and 17 are able to reduce bacterial loads in vivo. Because the results were modest for ciprofloxacin, it is possible that repeated treatment or systemic administration may be necessary to achieve efficacy. Although compound 17 was found to be inactive against in vivo nosocomial MRSA at a low dose using a murine model, our study facilitated a way forward for further mechanistic investigation on these new leads.

Finally, three geranyl-substituted structural analogs (12–14) of cannabigerol (CBG) were synthesized. Among these, compound 14 was found to be strongly active against the cancer signaling pathways, notably Smad, Myc, and Notch, with IC50 values between 1.2 μM and 4.8 μM in T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells. On the other hand, the anti-MRSA compounds 5 and 17 were found to be inactive against the panel of these transporter genes. A recent report by Morch et al. in 2021 [30] showed that Smad/TGF-β is a key player in probiotic protection against MRSA in C. elegans. In addition, in 2013, Choi et al. [31] reported that Stat3 induction helps host defense against MRSA pneumonia. Interestingly, the Notch pathway is activated by S. aureus toxins, in both in vivo and in vitro conditions [32], which suggests that compound 14 could have strong therapeutic potential against MRSA, due to its strong selective inhibition against the Notch pathway in this current study. Several reports suggested as association of MRSA with a significant increase in cancer mortality [5,6]. Thus, the inhibition of compound 14 against these cancer-signaling pathways could possibly decrease the morbidity of cancer conditions. Earlier, CBG, a close structural analog of 13, was not only reported for anti-MRSA activity [22], but also for its strong activity in colon, breast, and oral carcinomas [33,34,35]. In addition, CBG has been regarded as a potential therapeutic agent for glioblastoma [36]. This combination of earlier reports and our observations from the current study strongly suggest that compound 14 should be explored further for several cancers, particularly glioblastomas (brain tumors), and in combination therapies against MRSA. The co-occurrence of alterations in the multiple pathways suggests that compound 14 could be a potential lead molecule for targeted and combination therapies. Certain pathways, such as the RAS signaling pathway, are altered across many different tumor types [37], and the inhibition of compound 14 against RAS (moderate activity with IC50 value of 6.5 µM) indicates that it could be explored further for several cancers. The cross-talk between the other pathways in response to compound 14 treatment (Stat 3, AP-1, NFkB, E2F, and ETS with IC50 in the range of 4 µm to 5 µm) reflect functional interactions and dependencies. Overall, as Yu et al. [38] reported in 2022, molecular targeted therapies play a key role in the treatment of various cancers, and our results could be the starting point for the further development of compound 14.

4. Experimental

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotation was determined by an AUTOPOLVR IV polarimeter. The 1H- and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 or 500 MHz spectrometers. HMBC, HSQC, and ROESY were measured on an Agilent DD2-500 NMR spectrometer. The ESI-HRMS data was obtained by utilizing Agilent 6545 LC/Q-ToF and Model 6230 ToF (controlled by Agilent MassHunter Work Station, A.08.00) systems. All acquisitions were performed under a positive and negative ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 3000 V. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizer gas (25 psig) as well as the drying gas at 7 L/min at a drying gas temperature of 325 °C. Other parameters included sheath gas temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas flow, 7 L/min; skimmer, 65 V; Oct RF V, 750 V; and fragmentor voltage, 150 V. Ten microliters of sample were injected. Full scan mass spectra were acquired from m/z 100–1100. Data acquisition and processing was done using the MassHunter Workstation software (Qualitative Analysis Version B.10.00, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Accurate mass measurements of each spectrum from the data collected were obtained by means of reference ion correction using reference masses at m/z 121.0509 (protonated purine) and 922.0098 [protonated hexakis (1H, 1H, 3H-tetrafluoropropoxy) phosphazine or HP-921] in positive ion mode and at m/z 112.9856 (deprotonated trifluoroacetic acid-TFA) and 1033.9881 (TFA adducted HP-921) in negative ion mode. LC/MS data was measured using an Agilent 1290 Infinity series UHPLC instrument, coupled to an Agilent 6120 quadrupole mass spectrometer with a dual ESI and APCI interface. HPLC analysis was conducted on a Agilent technologies 1100 series with a diode array detector with semi preparative RP-HPLC (column: Luna C18(2) 10 µ, 250 × 10 mm; detector; UV 254 nm), using MeCN-H2O as the solvent. TLC analysis was carried out using analytical silica gel 60 PF254 and pre-coated alumina plates (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA; 0.25 mm thick). The plates were visualized under a UV lamp (254 nm) and sprayed with an anisaldehyde reagent, followed by heating.

4.2. Purification of Analogs by Centrifugal Preparative TLC and HPLC

Compounds 1–17 were separated from the reaction mixtures by customized centrifugal chromatography (Spin Chromatography system) [39], and compounds 2–4, 6, 8, 9+10, and 15–17 were further re-purified (>95%) by semi preparative RP-HPLC (column: Luna C18(2. 10 µ, 250 × 10 mm; detector; UV 254 nm), using MeCN-H2O as the solvent.

4.3. Synthesis of Compounds 1 and 2

(R)-(−)-α-Phellandrene (65.39 mg, 0.48 mmoL, >95%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to a mixture of stemofuran A (100 mg, 0.44 mmoL) and p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (PTSA, 25.17 mg, 0.13 mmol) in benzene (2.5 mL) at room temperature (RT) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h [20]. The reaction was quenched with aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue (200 mg) was purified by CPTLC (2 mm silica gel P254 disc, 45 RPM), and elution with EtOAc in hexane (1–20%) yielded compound 1 (50 mg, 32%) and a fraction containing 2 (15 mg, 9%). The fraction with 2 was further purified by semipreparative RP-HPLC, using 80% MeCN-H2O as the mobile phase to afford pure compound 2 (5 mg, 3%).

4.3.1. Compound 1

(1′R,2′R)-4-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-2′-isopropyl-5′-methyl-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-bihenyl]-2,6-diol; Gum, [α]26D +188 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.23 (m, 2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.35 (bs, 1H), 5.58 (s, 1H), 5.20 (bs, 1H), 3.96 (m, 1H), 2.22–2.16 (m, 2H), 1.85 (m, 1H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.72 (m, 1H), 1.68 (m, 1H), 1.46 (m, 1H), 0.94 (d, 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (d, 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.4, 154.8, 140.8, 129.9, 129.2, 124.2, 124.2, 122.9, 120.9, 117.8, 111.1, 101.4, 43.6, 35.7, 30.7, 28.0, 23.7, 23.1, 21.7, 16.4. ESIMS: m/z calcd for C24H27O3 [M+H]+: 363.19; found: 363.20. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H25O3 [M − H]−: 361.1809; found: 361.1809.

4.3.2. Compound 2

(1′S,2′S)-6-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-2′-isopropyl-5′-methyl-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2,6-diol; Gum, [α]26D +46 (c 0.33, CDCl3);1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (m, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (s, 1H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 3.92 (m, 1H), 2.11 (m, 2H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.73 (m, 1H), 1.47 (m, 1H), 0.73 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.1, 156.3, 154.8, 154.7, 140.4, 133.3, 128.7, 124.6, 124.1, 122.8, 121.3, 120.84, 111.2, 109.4, 105.6, 77.3, 77.0, 76.7, 43.1, 39.5, 30.7, 27.6, 23.7, 21.9, 21.6, 15.7. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H25O3 [M − H]−: 361.1809; found: 361.1816.

4.3.3. Synthesis of Compounds 3, 4, and 5

(−)-p-Mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol [(1R,4S)-1-methyl-4-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-2-enol] (72.96 mg, 0.48 mmoL) (Asta Tech, Bristol, PA, USA) was added to a mixture of stemofuran A (100 mg, 0.44 mmoL) and PTSA (25.17 mg, 0.13 mmoL) in benzene (3 mL) at RT and the reaction mixture was stirred for one hour. The reaction mixture was quenched with aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue (185 mg) was purified over a CPTLC (2 mm silica gel P254 disc, 45 RPM), and elution with (1% to 10%) EtOAc in hexane yielded a fraction rich with compounds 3 (13 mg, 7%) and 5 (75 mg, 48%), and a fraction rich with 4 (48 mg). The fraction rich with 4 was further purified semipreparative RP-HPLC (column: ODS 10 µ, 250 × 10 mm; detector; UV 254 nm), using 95% MeCN-H2O as solvent to afford pure compound 4 (12 mg, 2.7%).

4.3.4. Compound 3

(1′S,2′S)-4-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-5′-methyl-2′-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-1′,2′,3′,4′-terahydro-[1,1′ -biphenyl]-2,6-diol; Gum, [α]26D +79 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (m, 1H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 5.62 (bs, 1H), 4.70 (s, 1H), 4.61 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 3.96 (m, 1H). 2.50 (ddd, J = 14.6, 11.3, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (m, 1H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 1.89–1.83 (m, 2H), 1.85 (s, 3H), 1.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.5 × 2, 154.8 × 2, 148.8, 140.5, 129.9, 129.2, 124.2, 123.5, 122.8, 120.8, 117.5, 111.2, 111.1 × 2, 101.4 × 2, 46.1, 37.3, 30.4, 28.4, 23.6, 20.2. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H23O3 [M − H]−: 359.1653; found: 359 1653.

4.3.5. Compound 4

(1R,1′′S,2R,2′′S)-2′-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-5,5′′-dimethyl-2,2′′-di (prop-1-en-2-yl)1,1′′,2,2′′, 3,3′′,4,4′′-octahydro [1,1′,3′,1′′-terphenyl]-4′6′-diol; Gum, [α]26D 168 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.22 (m, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 6.42 (s, 1H), 5.71 (bs, 1H), 5.62 (bs,1H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 4.17 (d, J=6.7 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (s, 1H), 2.92 (s, 1H), 2.15 (s, 2H), 1.98 (m, 2H), 1.80 (s, 6H), 1.63 (m, 2H), 1.44 (m, 2H), 1.20 (s,3H), 1.08 (s,3H) 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.8, 154.6, 154.5, 146.7, 139.6, 139.1, 132.9, 128.6, 124.7, 124.5, 123.7, 122.6, 121.8, 120.6, 111.7, 111.5, 111.3, 108.1, 107.1, 77.3, 77.0, 76.8, 45.5, 45.2, 42.1, 41.7, 30.3, 30.1, 29.7, 27.9, 27.6, 23.6, 19.9, 19.3. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H37O3 [M − H]−: 493.2748; found: 493.2752.

4.3.6. Compound 5

(1S,2′S)-6′-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-5′-methyl-2′-(prop-1-en-2-yl)1,2′,3′4′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2,4-diol; Gum, [α]26D 82 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.4Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.1Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (m, 2H), 6.68 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (s, 1H), 5.80 (bs, 1H), 5.05 (bs, 1H), 4.47 (bs, 1H), 4.25 (bs, 1H), 4.0 (m, 1H), 2.54 (td, J = 10.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.25 (m, 1H), 2.11 (bs, 1H), 1.86 (s, 3H), 1.75 (m, 1H), 1.61 (m, 1H), 1.16 (s,3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.0, 156.3, 154.7, 154.7, 146.8, 140.4, 133.1, 128.8, 124.1, 122.8, 120.9, 120.7, 111.8, 111.3, 109.3, 105.6, 105.3, 45.9, 40.4, 30.3, 27.9, 23.7, 19.2. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H23O3 [M − H]−: 359.1653; found: 359.1648.

4.3.7. Synthesis of Compounds 6–11

(−)-p-Mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol (72.96 mg, 0.48 mmoL) was added to a mixture of pinosilvin (100 mg, 0.44 mmoL) and PTSA (25.17 mg, 0.13 mmoL) in benzene (3 mL) at RT and the reaction mixture was stirred for one hour. The reaction mixture was quenched with aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue (185 mg) was separated over a CPTLC (2 mm, silica gel, P254 disc, 45 RPM), and elution with EtOAc in hexane (1% to 10%) yielded a fraction rich with compound 6 (45 mg), 7 (42 mg, 28%), 8 (15 mg, 10%), a (1:0.2) mixture of cyclized products 9 and 10 (18 mg, 12%), and 11 (100 mg, 66%). The fraction rich with compound 6 was further purified by semipreparative RP-HPLC, using 80% MeCN-H2O as solvent to afford 6 (15 mg).

4.3.8. Compound 6

(1S, 1′′S, 2S, 2′′S)-5,5′′-Dimethyl-2,2′′-di(prop-1-en-2-yl)-6′-(E-styryl)-1,1′′,2,2′′, 3,3′′,4,4′′-octahydro-[1,1′:3′1′′-terpenyl]-2′,4′-diol; Gum, [α]26D 67 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (s,1H), 5.59 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 4.62 (s, 1H), 4.53 (s, 1H) 4.48 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (m, 1H), 2.47 (m, 1H), 2.30–2.14 (m, 4H), 1.84 (m, overlap,4H), 1.82 (s, 6H), 1.75 (s, 3H), 1.53 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.4, 153.8, 147.5, 140.3, 139.5, 137.9, 137.1, 130.7, 128.7, 128.6 × 2, 127.9, 127.3, 126.4 × 2, 124.5 × 2, 119.2, 117.5, 111.7, 111.4, 106.8, 46.5, 44.9, 40.4, 35.9, 30.4, 30.4, 28.4, 28.3, 23.7, 23.7, 21.0, 18.9. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H41O2 [M + H]+: 481.3112; found: 481.3106.

4.3.9. Compound 7

(1S, 1′′S, 2S, 2′′S)-5,5′′-Dimethyl-2,2′′-di(prop-1-en-2-yl)-2′-((E)-styryl-1,1′′,2,2′′,3,3′′, 4,4′′-octahydro-[1,1′:3′1′′-terpenyl]-4′,6′-diol; Gum, [α]26D 118 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.40 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (s, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (s, 1H), 5.58 (bs, 1H), 5.29 (bs, 1H), 4.56 (bs, 1H), 4.34 (bs, 1H), 3.72 (m, 1H), 2.50 (m, 2H) 2.18 (m, 2H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 1.77 (s, 6H), 1.43 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.7 × 2, 147.2 × 2, 140.5, 139.2 × 2, 137.3, 134.9, 128.6, 127.4 × 2, 126.1 × 2, 124.9, 119.7, 111.4 × 2, 104.6, 45.4 × 2, 53.4, 41.2 × 2, 30.2, 27.9 × 2, 23.6 × 2, 20.6 × 2. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H41O2 [M + H]+: 481.3101; found: 481.3104.

4.3.10. Compound 8

(1′S,2′S)-5′-Methyl-2′-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-6-(E)-styryl)-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydro-[1,1′bipenyl]-2,4-diol. Gum, [α]26D 176 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.50 (d, J= 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (t, J= 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.35, 7.28, 7.27 (m, 1H), 7.26, 7.25, 7.06, 7.02 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, brs, 1H), 6.54 (d, brs, 1H), 5.60 (s, 1H), 4.70 (s, 1H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 3.91 (m, 1H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 2.15 (s, 1H), 2.25 (m, 1H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.6, 154.3, 149.1, 140.4, 137.2, 137.10, 128.6 × 2, 128.1, 127.5, 126.4 × 2, 123.7, 116.4, 111.1, 108.1, 106.0, 46.2, 37.3, 30.4, 28.4, 23.7, 20.4. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H27O2 [M + H]+: 347.2006; found: 347.2019.

4.3.11. Compounds 9+10

Compound 9: (6S,10S)-6,6,9-Trimethyl-3-[(E)-styryl]-6,7,8,10-tetrahydro-6H-benzo [c]chromene-1-ol; Gum, 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (m, 2H), 7.30 (m, 1H), 7.21 d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (m, 2H), 3.36 (m, 1H), 2.22 (m, 2H), 1.94 (m, 1H), 1.74 (m, 1H), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 3H, 1H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.12 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.0, 154.7, 137.6, 137.5, 134.4, 128.7 × 2, 128.6, 128.0, 127.6, 126.6 × 2, 126.2, 116.2, 105.7, 103.7, 77.2, 46.4, 34.5, 31.1, 27.5, 25.2, 23.2, 18.9.

Compound 10: (5S, 6S)-2-Methyl-5-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-9-styryl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2H-2,6 -methanobenzo[b]-oxocin-7-ol; Gum, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (m, 1H), 4.99 (s, 1H), 3.5 (bs, 1H), 2.33 (bs, 1H), 1.61 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H). δ 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.6, 154.7, 145.6, 137.4, 136.4, 130.9, 128.8 × 2, 127.8, 126.5 × 2, 124.6, 117.3, 111.4, 103.8, 102.1, 74.6, 44.05, 35.3, 30.7, 30, 29.4, 22.8, 20.7. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H25O2 [M − H]−: 345.1860; found: 345.1857.

4.3.12. Compound 11

(1′S,2′S)-5′-Methyl-2′-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-4-[(E)-styryl-1′,2′,3′,4′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2,6-diol; Gum, [α]26D 0 (c 0.33, CDCl3), 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.43 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.6 (s, 1H), 4.64 (bs, 1H), 4.50 (bs, 1H), 3.77 (m, 1H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 2.12 (m, 1H), 1.82 (m, 2H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 1.8 (s, 3H), 1.54 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.4, 154.8, 147.2, 140.3, 139.7, 137.5, 131.4, 128.6 × 2, 127.8, 127.5, 126.4 × 2, 124.2, 120.1, 111.7, 105.8, 103.9, 45.5, 39.9, 30.2, 30.0, 23.7, 20.9. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H25O2 [M − H]−: 345.1860; found: 345.1861.

4.3.13. Synthesis of Compound 12–14

Geraniol (158.56 mg, 1.02 mmoL) was added to a mixture of pinosilvin (200 mg, 0.94 mmoL) and PTSA (53.8 mg, 0.26 mmoL) in benzene (5 mL) at RT and the reaction mixture was stirred for one hour. The reaction mixture was quenched with aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue (265 mg) was purified over a CPTLC (2 mm silica gel P254 disc, 45 RPM), and elution with (1% to 10%) EtOAc in hexane yielded compounds 12 (42 mg, 9%), 13 (72 mg, 22%), and 14 (50 mg, 15%).

4.3.14. Compound 12

2,4-bis[(E)-3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl]-5-(E)-styryl)benzene-1,3-diol; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (td, J = 7.2, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (tt, 6.6, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 5.32 (m, 1H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 5.10 (m, 2H), 3.48 (bd, J= 4.6 Hz, 4H), 2.14 (m, 4H), 2.10 (m, 4H), 1.86 (s, 6H), 1.64 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.7, 153.1, 139.0, 137.6, 137.4, 135.6, 132.0, 131.9, 130.4, 128.7 × 2, 127.5 × 2, 126.6, 126.5 × 2, 123.9, 123.8, 122.7, 121.6, 118.2, 113.8, 105.5, 39.8, 39.7, 26.5, 26.4, 25.73, 25.70, 22.8, 17.74, 17.73, 16.3, 16.2. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H43O2 [M − H]−: 483.3269; found: 483.3264.

4.3.15. Compound 13

2-[(E)-3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl]-5-[(E)-styryl)benzene-1,3-diol; Gum, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (td, J = 7.2, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (tt, 6.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (s, 2H), 5.33 (m, 1H), 5.09 (m, 1H), 3.48 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, Hz, 2H), 2.09–2.13 (m, 4H), 1.86 (s, 3H),1.73 (s, 3H), 1.64 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.2, 139.4, 137.2, 136.8, 132.1, 128.7 × 2, 128.6, 128.1, 127.6, 126.5 × 2, 123.7, 121.3, 113.4, 106.5 × 2, 39.7, 26.4, 25.7, 22.5, 17.7, 16.3. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H27O2 [M − H]−: 347.2017; found: 347.2013. NMR data of this compound agreed with those reported for amorphastibol [25].

4.3.16. Compound 14

4-[(E)-3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-diene-1-yl)-5-[(E)-styryl]benzene-1,3-diol; Gum, 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (td, J = 7.2, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (m, 1H), 5.07 (m, 1H), 3.47 (d, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (m, 2H), 2.07 (m, 2H), 1.85 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.60 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.6, 154.5, 138.6, 137.7, 137.4, 131.9, 131.2, 128.7, 127.7, 126.6, 126.5, 123.9, 122.3, 118.0, 105.5, 102.9, 39.7, 26.5, 25.7, 25.0, 17.7, 16.3. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H28O2 [M − H]−: 347.2017; found: 347.2018.

4.3.17. Synthesis of Compound 15 and 16

(−)-p-Mentha-2,8-diene-1-ol (290.3 mg, 1.9 mmoL) was added to a mixture of resveratrol (400 mg, 1.75 mmoL) and PTSA (99.9 mg, 0.52 mmoL) in benzene (5 mL) at RT and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with aqueous NaHCO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue (420 mg) was purified over a CPTLC (2 mm silica gel P254 disc, 45 RPM), and elution with (1% to 20%) EtOAc in hexane gave unreacted resveratrol, compounds 15 (27 mg, 3%) and 16 (9 mg, 1%).

4.3.18. Compound 15

(1S, 1′′S, 2S, 2′′S)-2′-((E)-4-Hydroxystyryl)-5,5′′-dimethyl-2,2′′-di(prop-1-en-2-yl) -1,1′′,2,2′′, 3,3′′,4,4′′-octahydro-[1,1′:3′1′′-terphenyl]-4′,6′-diol; Gum, [α]26D 0 (c 0.33, CDCl3);1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.30 (d, J= 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H) 6.65 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (bs, 1H), 6.08 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (bs, 2H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 3.76 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H 2.52 (m, 2H), 2.08–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.79 (s, 6H), 1.75 (m, 4H), 1.45 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.3, 154.6 × 2, 147.2 × 2, 140.8, 139.1 × 2, 134.4, 130.3, 127.5 × 2. 126.4, 125.1 × 2, 119.9 × 2, 115.6 × 2, 111.4 × 2, 104.5, 45.4 × 2, 41.2 × 2, 30.2 × 2, 28.0 × 2, 23.6 × 2, 20.5 × 2. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H39O3 [M − H]−: 495.2905; found: 495.2905.

4.3.19. Compound 16

(1S, 1′′S, 2S, 2′′S)-6′-((E)-4-hydroxystyryl)-5,5′′-dimethyl-2,2′′-di(prop-1-en-2-yl) -1,1′′,2,2′′, 3,3′′,4,4′′-octahydro-[1,1′:3′1′′-terphenyl]-2′,4′-diol; Gum, [α]26D 155 (c 0.33, CDCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34 (d, J = &.8 Hz, 2H), δ 7.11 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.6 (s, 1H), 4.56 (bs, 1H), 4.61 (bs, 1H), 4.5 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 2.5 (m, 2H), 2.26 (bs, 2H), 1.80 (s, 6H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.52 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.1, 154.3, 153.7, 147.5, 147.4, 140.2, 139.5, 137.4, 130.8, 130.2, 127.7 × 2, 125.9, 124.5, 119.1, 117.2, 115.5 × 2, 111.7, 111.4, 106.6, 46.5, 44.9, 40.3, 35.9, 30.58, 30.4, 28.4, 28.2, 23.7, 23.7, 21.01, 14.20. HRMS: m/z calcd for C34H41O3 [M + H]+: 497.3050; found: 497.3055

4.3.20. Synthesis of Compound 17

Compound 5 (45 mg, 0.12 mmoL) in ethyl acetate was hydrogenated with Adam’s catalyst, PtO2 (10%, 4.5 mg) at 40 psi at RT for 24 h, as previously published [40]. The catalyst was removed by filtration and the filtrate was evaporated to obtain a complete hydrogenated product (42 mg). Further purification of the portion of this mixture (20 mg) with RP-HPLC (column: ODS 10µ, 250 × 10 mm; detector; UV 254 nm) using 75% MeCN-H2O as solvent to afford 5-(benzofuran-2-yl)-4-((1R,2S,5R)-2-isopropyl-5-methylcyclohexyl)benzene-1,3-diol (17, 7.0 mg) as the major compound.

4.3.21. Compound 17

5-(Benzofuran-2yl)-4-[(1R,2S,5R)-2-isopropyl-5-methylcyclohexyl]benzene-1,3-diol; Gum, [α]26D 1 (c 0.33, CDCl3),1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.65 ((d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (m, 2H) 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.68 (bs, 1H), 6.37 (bs, 1H), 2.91 (m, 1H), 2.13 (m, 1H), 1.76 (m, 1H), 1.05 (m, 1H), 1.0 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 0.39 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.4, 156.1, 154.7, 153.85 133.3, 128.9, 124.0, 123.1, 122.7, 120.9, 111.2, 109.7, 105.2, 104.8, 44.5, 43.1, 40.8, 35.4, 33.3, 28.4, 25.3, 22.7, 21.6, 15.5. HRMS: m/z calcd for C24H27O3 [M − H]−: 363.1966; found: 363.1970, 399.1742 [M + Cl]−.

4.4. Antimicrobial Assay

Antimicrobial assays were carried out using a published method [10]. All organisms were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). These organisms included Candida albicans ATCC 90028, Cryptococcus neoformans ATCC 90113, Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 204305, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 1708 (MRSA), Escherichia coli ATCC 2452, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC BAA-2018, Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC 2146, and vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) ATCC 700221. Briefly, the antimicrobial activity was determined through a high throughput screening assay performed in a 384-well plate. Appropriate drug controls for bacteria and fungi were included in each assay. The concentration of compound/fraction responsible for 50% growth inhibition (IC50) was calculated using XLfit 4.2 software (IDBS, Alameda, CA), with fit model 201. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest test concentration that afforded no visual growth. Susceptibility testing was performed using a modified version of the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) method [41,42].

4.5. Antimicrobial Combination Study by Checkerboard Method

The combination study of the compounds was carried out in MRSA using the standard checkerboard method by Norden et al. 1979 [43]. Test samples were dissolved in 100% DMSO to the desired concentrations, and serially diluted (1:2) with 20% DMSO/saline. For checkerboard, compound 5, 17 and machaeriol C (i.e., previously isolated from Machaerium sp. [8,9]) were tested in the range of 2.5 µg/mL to 0.039 µg/mL. Inocula was prepared in cation-adjusted Mueller- Hinton broth to afford 5 × 105 colony forming units per mL. Samples were transferred to 96-well assay plates (10 µL) in a checkerboard layout followed by inocula (180 µL). The MIC of each antimicrobial agent alone and in combination was determined after incubation at 35 °C for 24 h. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) was calculated by using the following formula: FIC = [A*]/[A] + [B*]/[B], where [A*] is the MIC of compound A in the presence of compound B, [A] is the MIC of compound A alone, [B*] is the MIC of compound B in the presence of compound A, and [B] is the MIC of compound B alone. FIC: 0.5 = synergistic; 0.51–1.0 = additive; 1.1–2.0 = indifferent; >2.0 = antagonistic [44,45].

4.6. Bacterial Cultures for In Vivo Experiment

MRSA USA300 (kindly provided by Jorge Vidal, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA) was isolated on tryptic soy agar (TSA), then grown in culture for 16 h at 37 °C with shaking in tryptic soy broth (TSB). The bacteria were then diluted 100-fold in sterile TSB and grown to mid-logarithmic phase in tryptic soy broth (TSB). Serial dilutions were prepared in sterile PBS to achieve a target inoculum of 107 colony-forming units (CFU) per 0.03 mL.

4.7. In Vivo Anti-MRSA Nosocomial Assay in Murine Model

Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine and weighed. Each anesthetized mouse received a target inoculum of 107 CFU, as performed by Achouiti et al. [46]. The serial dilution and plating of the inoculum were carried out to verify the purity and accuracy of the dose. The actual dose was determined to be 2 × 107 CFU. Twelve hours after infection, the mice were anesthetized and administered 0.048 mL of vehicle ciprofloxacin (30 mg/Kg), compound 5 (30 mg/Kg), or compound 17 (30 mg/Kg). The vehicle composition, which was also used for suspension of the compounds and dilution of ciprofloxacin, was ethanol:DMSO:Cremophor EL:PBS (5:5:10:80 v/v).

Twenty-four hours after infection, the mice were anesthetized, then euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. Using a midline incision, each trachea was exposed and another incision was made partially through the middle of the trachea, being careful not to completely sever the trachea all the way through. Nasopharyngeal lavage was performed by placing a pipette into the tracheal incision, pushing 0.05 mL of sterile PBS through the trachea 2 times and into a 1.5 mL tube placed under the nose. The lavage fluid was then diluted and plated on TSA for bacterial load quantitation. Next, the whole lung was removed and homogenized before being plated and counted to determine bacterial loads.

4.8. Transcriptional Reporter Assays

T98G glioblastoma multiforme cells from ATCC were plated in white opaque 384-well plates at a density of 4300 cells/well in 30 μL of growth medium (DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep). On the next day, the medium was aspirated and replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were transfected with respective plasmids using X-tremeGENE HP transfection reagent (Roche). The luciferase vectors used in this assay are summarized in (Table S1, Supplementary Materials). After 24 h of transfection, the test agents were added to the transfected cells, followed 30 min later by an inducing agent (IL-6 for Stat 3, TGF-β for Smad, m-wnt3a for Wnt and PMA for AP-1, NFkB, E2F, Myc, ETS and Hedgehog). No inducer was added for FoxO, miR-21, Ras, AhR and pTK vector control. After 4 h or 6 h of induction, the cells were lysed by the addition of a One-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The light output was detected in a Glomax Multi+ detection system with Instinct Software (Promega). This luciferase assay determined whether the test agent was able to inhibit the activation of the cancer-related signaling pathways. In the case of FoxO, mi-R21-, Ras-, and AhR-enhanced luciferase activity by the test agents was assessed [47].

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the National Center for Natural Products Research for providing facilities to execute all of the chemical and biological work of this project.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules27196604/s1, Figure S1–S48: NMR and HRMS spectra; Table S1: List of luciferase vectors.

Author Contributions

I.M., N.P.D.N. and M.K. conceptualized the study and planned the experiments and spectral analysis for chemistry work; N.P.D.N. and M.K. organized and executed the synthesis; M.W. and B.A. executed the LCMS and HRMS work; J.Z. (Jianping Zhao), executed the NMR spectra; S.T. and M.M.B. planned and executed the in vitro antimicrobial and checkerboard assay; P.B. and J.Z. (Jin Zhang) planned and executed the cancer signaling assay; M.E.M. planned and supervised the in vivo MRSA nosocomial assay at the University of Mississippi Medical Center; M.A.C., K.M.L. and O.I.W. executed the in vivo nosocomial assay at the University of Mississippi Medical Center; I.M., N.P.D.N., M.K. and M.E.M. prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data provided in Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by USDA-ARS SCA grant # 58-6060- 6-015 and overhead funds from the National Center for Natural Products Research at the University of Mississippi and the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van Duin D., Paterson D.L. Multidrug resistant bacteria in the community: An Update. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2020;34:709–722. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John Dyer J. The Long arm of MRSA. [(accessed on 20 December 2021)];Infect. Control Today. 2021 5 Available online: https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/thanks-to-covid-19-mrsa-makes-a-comeback. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adalbert J.R., Varshney K., Tobin R., Pajaro R. Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: A scoping review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:985. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06616-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC . Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus. CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA: 2022. [(accessed on 20 January 2022)]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/healthcare/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhouqi Li Z., Zhuang H., Wang G., Wang H., Dong Y. Prevalence, predictors, and mortality of bloodstream infections due to methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus in patients with malignancy: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:74. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05763-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An J., Li Z., Dong Y., Ren J., Guo K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection exacerbates NSCLC cell metastasis by up-regulating TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2016;62:1–7. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2016.62.8.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhammad I., Li X.C., Dunbar D.C., ElSohly M.A., Khan I.A. Antimalarial (+)-trans-hexahydrodibenzopyran derivatives from Machaerium multiflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1322–1325. doi: 10.1021/np0102861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhammad I., Li X.C., Jacob M.R., Tekwani B.L., Dunbar D.C., Ferreira D. Antimicrobial and antiparasitic (+)-trans-hexahydrodibenzopyrans and analogues from Machaerium multiflorum. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:804–809. doi: 10.1021/np030045o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhammad I., Jacob M.R., Ibrahim M.A., Raman V., Kumarihamy M., Wang M., Al-Adhami T., Hind C., Clifford M., Martin B., et al. Antimicrobial constituents from Machaerium Pers.: Inhibitory activities and synergism of machaeriols and machaeridiols against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, and permeabilized gram-negative pathogens. Molecules. 2020;25:6000. doi: 10.3390/molecules25246000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyota M., Shimamura T., Ishii H., Renner M., Braggins J., Asakawa Y. New bibenzyl cannabinoid from the New Zealand liverwort Radula marginata. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002;50:1390–1392. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chicca A., Schafroth M.A., Reynoso-Moreno I., Erni R., Petrucci V., Carreira E.M., Gertsch J. Uncovering the psychoactivity of a cannabinoid from liverworts associated with a legal high. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaat2166. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botta B., Gacs-Baitz E., Vinciguerra V., Delle Monache G. Three isoflavanones with cannabinoid-like moieties from Desmodium canum. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:599–602. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka T., Ohyama M., Kawasaka Y., Iinuma M. Tetrapterols A and B: Novel flavonoid compounds from Sophora tetraptera. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9043–9044. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(94)88422-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appendino G., Simon Gibbons S., Giana A., Pagani A., Grassi G., Stavri M., Smith E., Rahman M.M. Antibacterial cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: A structure-activity study. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1427–1430. doi: 10.1021/np8002673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q., Huang Q., Chen B., Lu J., Wang H., She X., Pan X. Total synthesis of (+)-machaeriol D with a key regio- and stereoselective SN2′ reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:3651–3653. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dethe D.H., Erande R.D., Mahapatra S., Das S., Kumar B. Protecting group free enantiospecific total syntheses of structurally diverse natural products of the tetrahydrocannabinoid family. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:2871–2873. doi: 10.1039/C4CC08562K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotter F., Studer A. Short and divergent total synthesis of (+)-machaeriol B, (+)-machaeriol D, (+)-Δ8-THC, and Analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:8547–8550. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seephonkai P., Papescu R., Zehl M., Krupitza G., Urban E., Kopp B. Ferruginenes A−C from Rhododendron ferrugineum and their cytotoxic evaluation. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:712–717. doi: 10.1021/np100778k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Q., Wang Q., Zheng J., Pan X., She X. A general route to 5,6-seco-hexahydrodibenzopyrans and analogues: First total synthesis of (+)-machaeridiol B and (+)-machaeriol B. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.10.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascal M., Hafezi N., Wang D., Hu Y., Serra G., Dallas M.L., Spencer J.P. Synthetic, non-intoxicating 8, 9-dihydrocannabidiol for the mitigation of seizures. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7778. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44056-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blaskovich M.A.T., Kavanagh A.M., Elliott A.G., Zhang B., Ramu S., Amado M., Lowe G.J., Hinton A.O., Pham D.M.T., Zuegg J., et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:7. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farha M.A., El-Halfawy O.M., Gale R.T., MacNair C.R., Carfrae L.A., Zhang X., Jentsch N.G., Magolan J., Brown E.D. Uncovering the hidden antibiotic potential of cannabis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:338–346. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulko P.S., Al-Abed Y. Treatment Method, Compounds, and Method of Increasing trpv2 Activity. WO2016138383 A1. 2016 September 1;

- 24.Kemal M., Wahba Khalil S.K., Rao N.G., Woolsey N.F. Isolation and identification of a cannabinoid-like compound from Amorpha species. J. Nat. Prod. 1979;42:463–468. doi: 10.1021/np50005a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marzullo P., Foschi F., Coppini D.A., Fanchini F., Magnani L., Rusconi S., Luzzani M., Passarella D. Cannabidiol as the substrate in acid-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:2894–2901. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S., Wang L., Zhang W., Wei Y. Chemical constituents of the antiulcer purified fractions of Lindera reflexa Hemsl. and its quantitative analysis. Fitoterapia. 2015;105:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu Y., Sun X., Chen S., Duan Y., Han Y. Secondary metabolites from the roots of Lindera reflexa Hemsl. Fitoterapia. 2021;105:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia L., Lee Y.R. A Short Total synthesis for biologically interesting (+)-and (-)-machaeriol A. Synlett. 2008;11:1643–1646. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thapa D., Lee J.S., Heo S.W., Kang K.W., Kwak M.-K., Choi H.G., Kim J.-A. Novel hexahydrocannabinol analogs as potential anti-cancer agents inhibit cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;650:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mørch M.G.M., Møller K.V., Hesselager M.O., Harders R.H., Kidmose C.L., Buhl T., Fuursted K., Bendixen E., Shen C., Christensen L.G., et al. The TGF-β ligand DBL-1 is a key player in a multifaceted probiotic protection against MRSA in C. elegans. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:10717. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89831-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi S.M., McAleer J.P., Zheng M., Pociask D.A., Kaplan M.H., Qin S., Reinhart T.A., Kolls J.K. Innate Stat3-mediated induction of the antimicrobial protein Reg3γ is required for host defense against MRSA pneumonia. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:551–561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez S.L., Nelson M., Sampedro G.R., Bagrodia N., Defnet A.M., Lec B., Emolo J., Kirschner R., Wu L., Biermann H., et al. Staphylococcus aureus alpha toxin activates Notch in vascular cells. Angiogenesis. 2019;22:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s10456-018-9650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrelli F., Pagano E., Romano B., Panzera S., Maiello F., Coppola D., De Petrocellis L., Buono L., Orlando P., Izzo A.A. Colon carcinogenesis is inhibited by the TRPM8 antagonist cannabigerol, a Cannabis-derived non-psychotropic cannabinoid. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2787–2797. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snell A. Undergraduate Honors Thesis. University of Northern Colorado; Greeley, CO, USA: May 4, 2021. Meta-Analysis of Cannabigerol Effects on Breast Cancer Tissue Cells. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baek S.H., Kim Y.O., Kwag J.S., Choi K.E., Jung W.E., Han D.S. Boron trifluoride etherate on silica-A modified lewis acid reagent (VII). Antitumor activity of cannabigerol against human oral epitheloid carcinoma cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1998;21:353–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02975301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lah T.T., Novak M., Almidon M.A.P., Marinelli O., Baškovič B.Z., Majc B., Bošnjak M.M.R., Breznik B., Zomer R., Nabissi M. Cannabigerol is a potential therapeutic agent in a novel combined therapy for glioblastoma. Cells. 2021;10:340. doi: 10.3390/cells10020340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez-Vega F., Mina M., Armenia J., Chatila W.K., Luna A., La K.C., Dimitriadoy S., Liu D.L., Kantheti H.S., Saghafinia S., et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cells. 2018;173:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu D., Qi S., Guan X., Yu W., Yu X., Cai M., Li Q., Wang W., Zhang W., Qin J.J. Inhibition of STAT3 Signaling Pathway by Terphenyllin Suppresses Growth and Metastasis of Gastric Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:870367. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.870367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ilias M., Samoylenko V., Gillium V.D. Preparation of pre-coated rp-rotors and universal chromatorotors, chromatographic separation devices and methods for centrifugal preparative chromatography. US20140224740A1. application publication, 14 September. US Patent. 2014

- 40.Ben-Shabat S., Hanuš L.O., Katzavian G., Gallily R. New cannabidiol derivatives: Synthesis, binding to cannabinoid receptor, and evaluation of their antiinflammatory activity. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1113–1117. doi: 10.1021/jm050709m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods G.L., Brown-Elliott B.A., Conville P.S., Desmond E.P., Hall G.S., Lin G., Pfyffer G.E., Ridderhof J.C., Siddiqi S.H., Wallace R.J., Jr., et al. Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardia, and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wikler M.A. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norden C.W., Wentzel H., Keleti E. Comparison of techniques for measurement of in vitro antibiotic synergism. J. Infect. Dis. 1979;140:629–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh M.H., Chen M.Y., Victor L.Y., Chow J.W. Synergy assessed by checkerboard a critical analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1993;16:343–349. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90087-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacob M.R., Hossain C.F., Mohammed K.A., Smillie T.J., Clark A.M., Walker L.A., Nagle D.G. Reversal of fluconazole resistance in multidrug efflux-resistant fungi by the Dysidea arenaria sponge sterol 9alpha,11alpha-epoxycholest-7-ene-3beta,5alpha,6alpha,19-tetrol 6-acetate. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:1618–1622. doi: 10.1021/np030317n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Achouiti A., van der Meer A.J., Florquin S., Yang H., Tracey K.J., van’t Veer C., de Vos A.F., van der Poll T. High-mobility group box 1 and the receptor for advanced glycation end products contribute to lung injury during Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Crit. Care. 2013;17:R296. doi: 10.1186/cc13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton K.L., Sheehan S.A., Retzbach E.P., Timmerman C.A., Gianneschi G.B., Tempera P.J., Balachandran P., Goldberg G.S. Effects of Maackia amurensis seed lectin (MASL) on oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) gene expression and transcriptional signaling pathways. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021;147:445–457. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data provided in Supplementary Materials.