Abstract

Five outbreaks of infection (three pertussis, one parapertussis, and one mixed) in schools were studied prospectively. Nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained from a total of 697 children for culture of Bordetella organisms. Of 50 vaccinated children with culture-confirmed Bordetella infections (29 with pertussis and 21 parapertussis), 40 were symptomatic and 10 remained symptom-free. Smaller numbers of colonies were recovered from the nasopharyngeal swabs of the asymptomatic children than from those of the symptomatic children. Older children had longer durations of illness than younger ones. Our results indicate that during outbreaks children who do not develop disease may have small amounts of Bordetella organisms in their nasopharynges and/or better immune defenses against the disease.

Pertussis remains endemic and epidemic among immunized populations (2). In countries with high vaccination coverage rates, the occurrence of pertussis has shifted to older children, adolescents, and adults (2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15). In Finland, where the pertussis vaccination coverage rate is 98% (7), pertussis is not uncommon in school-age children, whereas preschool-age children may have more asymptomatic infections and shorter illnesses (9). However, it is not known whether there is an association between bacterial numbers in the nasopharynges and the development of symptoms in patients. Furthermore, it remains to be elucidated whether the outcome of Bordetella infections changes with time among school-age children, which would indicate changing immunity. In the study described here we studied the number of bacteria cultured from nasopharyngeal swabs, the duration of illness, and the age of patients with Bordetella infections during outbreaks in schools.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pertussis vaccination was introduced in Finland in 1952. The vaccine is manufactured by the National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland, and contains 5 × 109 formalin-killed Bordetella pertussis organisms per dose in combination with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids. The vaccine is administered at 3, 4, 5, and 24 months of age, and in Finland the coverage rate for the four doses is 98% (7). During a prospective cohort study of the prevalence of positive cultures and/or positive PCRs for B. pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis (8), we found that Bordetella infections are common in Finland and that about one-third of these infections are caused by B. parapertussis. Moreover, the results obtained from the prospective study also suggested that pertussis vaccination may provide some protection against B. parapertussis (8).

From 1992 through 1996, five outbreaks of infection (three pertussis, one parapertussis, and one mixed) in schools in southwestern Finland were studied prospectively (Table 1). Four outbreaks (outbreaks I, II, IV, and V) were described earlier (6, 9, 10, 16). Nasopharyngeal swabs for culture of Bordetella organisms were obtained from a total of 697 children. For all children in schools involved in outbreaks I to IV, nasopharyngeal swabs were available for culture, and for 234 pupils in the school involved in outbreak V, 200 (84%) nasopharyngeal swabs were available for culture. A total of 51 children had positive cultures for Bordetella, and none of them was found to harbor both organisms in a specimen. A 9-year-old girl was culture positive for B. pertussis but was symptom-free at the time of sampling. She developed a cough 4 days after the sampling, and data for this girl were thus excluded from the following analysis.

TABLE 1.

Children studied for isolation of Bordetella organisms during five school outbreaks from 1992 to 1996

| Outbreak (yr) | No. of childrena (age range [yr]) | No. of children culture positive

forb:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B. pertussis | B. parapertussis | ||

| I (1992) | 39 (7–12) | 13 | |

| II (1992) | 179 (7–12) | 4 | |

| III (1994) | 156 (13–16) | 11 | |

| IV (1995) | 123 (7–12) | 3c | 10 |

| V (1996) | 200 (13–16) | 10 | |

For all children in schools involved in outbreaks I to IV, nasopharyngeal swabs were available for culture, and for 234 pupils in the school involved in outbreak V, 200 (84%) swabs were available for culture.

None of the patients harbored both organisms in a specimen.

A 9-year-old girl was symptom-free at the time of sampling and culture positive for B. pertussis, and she developed cough 4 days after the sampling; data for this girl were thus excluded from the analysis.

Fifty children (24 boys and 26 girls; median age, 12 years; age range, 7 to 16 years) had culture-confirmed Bordetella infections; 29 had pertussis and 21 had parapertussis. Forty-six had received four doses and four had received three doses of the Finnish diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine. During the follow-up, three pertussis and seven parapertussis patients were asymptomatic. The median age of the 10 asymptomatic patients was 10.5 years (age range, 7 to 16 years). Of the 26 symptomatic pertussis patients, 23 had paroxysmal cough, 3 had vomiting, and 1 had whooping; of the 14 symptomatic parapertussis patients, 13 had paroxysmal cough but none had vomiting or whooping. The median age of the 40 symptomatic patients was 11.5 years (age range, 7 to 16 years). At the time of sampling, the median duration of cough in 40 patients with symptomatic infections was 8 days (range, 0 to 30 days). No prophylactic antibiotics were given to these study subjects. After the infection was confirmed by culture, all subjects were treated with erythromycin. Hospitalization was not needed for any subject.

Detailed clinical information on each subject was obtained by means of at least two structured questionnaires that asked about the date of onset and the nature of the symptoms, including cough with or without paroxysms, whooping, or vomiting. The questionnaires were completed by the childrens’ parents. Children who had no sign of cough at the time of sampling and during the follow-up period were considered to be asymptomatic, and all children who had cough at the time of sampling were monitored until the end of the coughing episodes.

Nasopharyngeal swab (calcium alginate) specimens were collected by passing the swabs through the nares into the posterior nasopharynx and rotating the swabs for a few seconds (5). One pernasal swab was obtained from one study subject, and no multiple sampling was performed. After specimen collection, the swabs were immediately streaked onto charcoal agar plates supplemented with cephalexin. In the laboratory, the culture plates were incubated in a humid atmosphere at 35°C and monitored daily for 7 days. Suspected colonies were Gram stained and tested by slide agglutination with antisera to B. pertussis and B. parapertussis (Murex Diagnostics, Dartford, England). In addition to agglutination, pigment formation on tyrosine agar and urease activity were used for identification of B. parapertussis. The identities of the B. pertussis and B. parapertussis strains were confirmed by gas-liquid chromatography. All the swabs were collected and streaked by a physician in our research group, and the counting of the Bordetella colonies on culture plates was performed by an experienced technician.

To assess whether the technique of streaking of the swabs was uniform, two strains each of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis, all recent clinical isolates, were used for the preparation of bacterial suspensions. Bacteria were harvested from the culture plates and were suspended in 3 ml of sterile physiological saline. Serial 10-fold dilutions were made from each of two suspensions. Five swabs (calcium alginate) were placed into each of the dilutions for 2 min, and the swabs were then streaked onto charcoal agar plates without cephalexin. The culture plates were incubated as described above. For B. parapertussis, the colonies on the plates were counted after a 2-day incubation, and for B. pertussis, the colonies on the plates were counted after a 4-day incubation. All cultures were performed by the same technician who had counted the Bordetella colonies on the culture plates containing the clinical swabs.

The Student t test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used for analysis of statistical significance, and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for analysis of correlations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The mean number of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis colonies recovered from swabs placed in serial 10-fold dilutions is shown in Table 2. The number of colonies recovered correlated with the concentration of bacterial suspensions in which the swabs were placed (r = 0.994; P < 0.01). Although the variation in the number of colonies recovered from five swabs placed in a dilution was small, the sampling and streaking from serial dilutions may not necessarily be analogous to sampling and streaking of specimens from the nasopharyngeal mucosa.

TABLE 2.

Mean number of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis colonies recovered from swabs placed in serial 10-fold dilutionsa

|

B.

pertussis

|

B. parapertussis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concn of bacterial dilution (no. of bacteria/ml) | Colony no. recovered from five swabs (mean ± SD) | Concn of bacterial dilution (no. of bacteria/ml) | Colony no. recovered from five swabs (mean ± SD) |

| 1.4 × 105 | 395.0 ± 131.8 | 4 × 104 | 114.0 ± 15.5 |

| 1.4 × 104 | 27.6 ± 6.2 | 4 × 103 | 6.8 ± 1.3 |

| 1.4 × 103 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 4 × 102 | 1.8 ± 0.8 |

| 1.4 × 102 | 0 | 4 × 101 | 0 |

Five swabs were placed into each of the dilutions for 2 min, removed, and streaked onto charcoal agar plates. The number of colonies on the plates was counted after a 2-day culture of B. parapertussis and after a 4-day culture of B. pertussis. For bacterial concentrations greater than 1.4 × 105 for B. pertussis and 4 × 104 for B. parapertussis, the numbers of colonies recovered from all the swabs were more than 1,000.

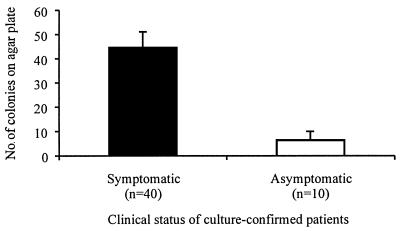

For the patients with culture-confirmed Bordetella infections, significantly smaller numbers of colonies were recovered from the nasopharyngeal swabs of the children with asymptomatic infections (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 6.3 ± 3.7 colonies) than from those of the patients with symptomatic infections (44.4 ± 6.7 colonies) (P = 0.004) (Fig. 1). For the pertussis patients, the numbers of colonies recovered from the swabs of children with asymptomatic and symptomatic infections were 2.9 ± 2.5 and 56.4 ± 6.1 colonies, respectively, and for the parapertussis patients, the corresponding numbers were 8.8 ± 3.8 and 28.5 ± 7.8 colonies, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Mean colony numbers for Bordetella organisms recovered from the nasopharyngeal swabs of children with asymptomatic and symptomatic infections.

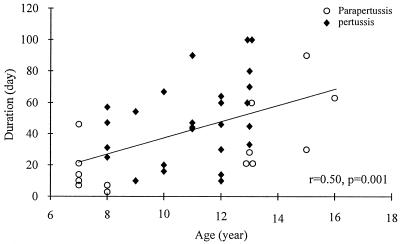

The duration of illness in 40 patients with symptomatic Bordetella infections correlated positively with age (r = 0.50; P = 0.001; Fig. 2). The duration of illness in 26 patients with pertussis tended to correlate with age (r = 0.39; P = 0.052), and the duration of illness in 14 patients with parapertussis correlated with age (r = 0.66; P = 0.010). The mean duration of illness in the pertussis patients (48.6 ± 26.1 days) was longer than that in the parapertussis patients (30.6 ± 25.5 days) (P = 0.042).

FIG. 2.

Duration of illness and age of children (n = 40) with Bordetella infections during school outbreaks. The oblique line is a regression line.

No difference in the ages between children who received three and four doses of pertussis vaccine in infancy and the number of colonies recovered from their nasopharyngeal swabs was found. The number of colonies recovered from nasopharyngeal swabs was not associated with the time of sampling at postinfection (P = 1).

Our results indicate that during outbreaks in schools there is considerable variation in the numbers of Bordetella organisms in the respiratory tracts of previously immunized children. Children who remained asymptomatic had significantly smaller numbers of organisms than symptomatic children. Another observation was that when the symptoms evolved, their durations were longer the older the children.

There are two plausible explanations, which are not mutually exclusive, for the small bacterial numbers in the respiratory tracts of the asymptomatic children. First, the number of bacteria infecting these children may have been below the dose capable of causing symptoms, as hypothesized by Fine and Clarkson (4). Second, the immune defense mechanisms of these children may have limited bacterial growth below the level that causes disease (6, 10, 14). Moreover, the possible inoculum effect might explain, at least in part, the difficulties in studying a correlation between levels of antibodies against Bordetella organisms and protection against clinical disease (1).

Increasing evidence indicates that the protection offered by pertussis vaccination decreases with time (11, 12). Jenkinson (11) showed that the efficacy of the British vaccine was complete only for the first year after immunization and then fell gradually, being around 50% by the sixth year (11). A similar phenomenon has also been observed in Finland (9). It is therefore interesting to evaluate the specific immune status of these children with culture-confirmed Bordetella infections. During outbreak I (10), 13 children proved to be culture positive for B. pertussis, and they all had symptoms at the time of sampling. The first serum samples from more than two-thirds of the children (9 of 13) had low levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies to pertussis toxin, filamentous hemagglutinin, and pertactin of B. pertussis. However, during this outbreak we found that children with higher levels of antibodies against filamentous hemagglutinin remained healthy, whereas those with lower antibody levels developed the diseases. During outbreak IV (6), 12 children who had high levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies to filamentous hemagglutinin and pertactin of B. pertussis in the first serum samples remained symptom-free. Of the 12 asymptomatic children, half were culture positive for B. parapertussis.

Our results indicate that during outbreaks children who do not develop disease may have small amounts of Bordetella organisms in their nasopharynges and/or better immune defenses against the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Birgitta Aittanen for excellent technical assistance and to Erkki Nieminen for help in preparation of the figures.

The study was supported by the Academy of Finland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ad Hoc Group for the Study of Pertussis Vaccines. Placebo-controlled trial of two acellular pertussis vaccines in Sweden: protective efficacy and adverse events. Lancet. 1988;i:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black S. Epidemiology of pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:S85–S89. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199704001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported vaccine-preventable diseases: United States, 1993, and the Childhood Immunization Initiative. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1994;43:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fine P E M, Clarkson J A. Reflections on the efficacy of pertussis vaccines. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:866–883. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilchrist M J R. Bordetella. In: Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Herrmann K L, Isenberg H D, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 471–477. [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Q, Edelman K, Arvilommi H, Mertsola J. Protective role of immunoglobulin G antibodies to filamentous hemagglutinin and pertactin of Bordetella pertussis in Bordetella parapertussis infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:793–798. doi: 10.1007/BF01701521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Q, Schmidt-Schläpfer G, Just M, Matter H C, Nikkari S, Viljanen M K, Mertsola J. Impact of polymerase chain reaction on clinical pertussis research: Finnish and Swiss experiences. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1288–1295. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Q, Viljanen M K, Arvilommi H, Aittanen B, Mertsola J. Whooping cough caused by Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis in an immunized population. JAMA. 1998;280:635–637. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Q, Viljanen M K, Nikkari S, Lyytikäinen R, Mertsola J. Outcomes of Bordetella pertussis infection in different age groups of an immunized population. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:873–877. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He Q, Viljanen M K, Ölander R-M, Bogaerts H, Grave D D, Ruuskanen O, Mertsola J. Antibodies to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis and protection against whooping cough in schoolchildren. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:705–708. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkinson D. Duration of effectiveness of pertussis vaccine: evidence from a 10 year community study. Br Med J. 1988;296:612–614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6622.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert H J. Epidemiology of a small pertussis outbreak in Kent County, Michigan. Public Health Rep. 1965;80:365–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mink C M, Cherry J D, Christenson P, Lewis K, Pineda E, Shlian D, Dawson J A, Blumberg D A. A search for Bordetella pertussis infection in university students. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:464–471. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Szu S C. Perspective: hypothesis: serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1387–1398. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson P W, Goldberg H, Jarvie B H, Smith D D, Whybin L R. Bordetella pertussis infection: a cause of persistent cough in adults. Med J Aust. 1987;147:522–525. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1987.tb120392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran Minh N N, He Q, Edelman K, Ö lander R-M, Viljanen M K, Arvilommi H, Mertsola J. Cell-mediated immune responses to antigens of Bordetella pertussis and protection against pertussis in school children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:366–370. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199904000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]