Abstract

Maintaining healthy skin is important for a healthy body. At present, skin diseases are numerous, representing a major health problem affecting all ages from neonates to the elderly worldwide. Many people may develop diseases that affect the skin, including cancer, herpes, and cellulitis. Long-term conventional treatment creates complicated disorders in vital organs of the body. It also imposes socioeconomic burdens on patients. Natural treatment is cheap and claimed to be safe. The use of plants is as old as mankind. Many medicinal plants and their parts are frequently used to treat these diseases, and they are also suitable raw materials for the production of new synthetic agents. A review of some plant families, viz., Fabaceae, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, etc., used in the treatment of skin diseases is provided with their most common compounds and in silico studies that summarize the recent data that have been collected in this area.

Keywords: skin diseases, herbal medicine, ethnobotany, granzyme B, human leukocyte elastase, molecular docking

1. Introduction

Molecular docking is an in silico procedure that is able to predict the mechanism of binding of a suggested ligand to its macromolecular target during the formation of a stable complex. Therefore, docking has become of great importance for the illustration of molecular interactions of natural compounds with different receptors [1,2,3].

The skin, the largest organ of the human body, functions as a physical barrier and an exterior interface of the body with the outer environment. The skin prevents the body from the invasion of external pathogens, as well as mechanical, thermal, and physical injuries from any substance that can be hazardous to humans. Just like any other organ and system of the body, this system is also very complex. The skin, with its derivatives such as nails, sweat glands, oil glands, and hair, makes up the integumentary system [4]. It is an incredible organ that protects the whole body. It consists of three main layers, including the epidermis (outermost layer), which consists of three types of cells, i.e., squamous cells, basal cells, and melanocytes; the second layer of the skin, the dermis, which contains blood and lymph vessels, hair follicles, etc.; and the subcutaneous fat layer. The focus on skin health is because everyone wants clearer, healthier, younger, and fresher skin, as skin-related complications can cause problems related to mental health, as well as low self-esteem [5].

Herbal medicine can be traced back to ancient civilizations. It entails the use of plants for medicinal purposes to cure illnesses and improve overall health [6]. Although herbal plants are low in toxicity and readily available, they play an important role in not only pharmacological research and drug production but also as plant components, being used specifically as therapeutic agents for drug synthesis [7]. The most widely used plant parts in the preparation of traditional medicines are the leaves (62%), either alone or in combination with other plant parts [6,7].

Skin disease refers to problems with the surface layer of the skin. Skin disorders have a serious impact on well-being and are difficult to manage due to their persistence [8]. Several microorganisms trigger skin ailments, including boils, scratching ringworm, skin diseases, leprosy, injury, skin infections, eczema, skin allergy inflammation, scabies, and psoriasis [9].

Scabies, a parasitic infection, has always been the most prevalent skin disorder, but, in some areas, it is entirely absent [10]. Sarcoptes scabiei is the mite that causes scabies. Infection with the scabies worm causes a rash of vesicles, nodules, and papules. The majority of this is due to host hypersensitivity, but the direct impact of worm invasion also plays a significant role [11].

A rash is a red, inflamed patch of skin or a set of discrete spots. Irritation, inflammation and allergies, fundamental conditions, and structural issues may all contribute to these symptoms. Acne, eczema, psoriasis, hives, etc., are causes of rashes [4].

Atopic eczema, a chronic condition that affects people who are genetically organized to overreact towards environmental stimuli, has become an inflammatory disease. It is often seen in people with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopy symptoms. Eczema is a common skin problem in children. Severe skin dryness and inflammation, scaly patches, redness, and lichenified plaque with abrasions are the most common dermatitis symptoms [12].

Acne is a contagious disease and one of the most common in humans. Acne leads to seborrhea, papules, comedowns, blackheads, nodules, and scars [13]. Acne is most often found on the face, chest area, and back of people who have a large number of oil glands [14].

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin problem that causes keratinocytes, excessive proliferation resulting in scaly patches, extreme inflammation, and erythema [15].

The uncontrolled development of cells present in the skin is known as skin cancer. It occurs due to unfixed DNA damage to skin cells, most commonly due to UV from sunlight, causing mutations and even genetic abnormalities. This causes skin cells to grow rapidly, resulting in the formation of malignant tumors [16].

A burn is considered tissue damage due to fire, chemicals, or radiation. Burn wounds are classified as superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness. Swelling, epithelization, wound contraction, and granulation are all part of the healing process after a burn wound [17].

The current review presents the effect of different medicinal plants and FDA-approved formulas on the management of various skin disorders. A molecular docking study was conducted for major components of these medicinal plants on the active sites of granzyme B and human leukocyte elastase (HLE) enzymes, aiming to identify the potential compounds or class of compounds that may be responsible for the ameliorative effects on different skin ailments.

2. Medicinal Plants and Skin Disorders

Medicinal plants reported for the management of skin disorders (Table 1) are classified below according to their uses.

Table 1.

Botanical sources and medicinal plants used to treat different skin disorders.

| No. | Botanical Source (Latin Name, Common Name, Family) | Uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Skin infections | ||

| 1 | Achyranthes aspera | Used to treat boils and scabies | [18] |

| Prickly chaff flower | |||

| Family Amaranthaceae | |||

| 2 | Aconitum chasmanthum | Used to treat mumps and measles | [19] |

| Gaping monkshood | |||

| Family Ranunculaceae | |||

| 3 | Butea monosperma | Used to treat skin diseases such as inflammation | [20] |

| Flame of forest | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 4 | Boerhavia diffusa | Used to treat abscesses | [21] |

| Tar vine, wine flower | |||

| Family Nyctaginaceae | |||

| 5 | Curcuma longa | Used to treat skin inflammation | [22] |

| Turmeric | |||

| Family Zingiberaceae | |||

| 6 | Crocus sativus | Used to treat psoriasis | [23] |

| saffron | |||

| Family Iridaceae | |||

| 7 | Commelina benghalensis | Used to treat wound infection | [24] |

| Tropical spiderwort | |||

| Family Commelinaceae | |||

| 8 | Cyperus difformis | Used to treat skin infections | [25] |

| Family Cyperaceae | |||

| 9 | Cassia tora | Used to treat psoriasis | [26] |

| Stinking cassia | |||

| Family Caesalpiniaceae | |||

| 10 | Capsicum frutescens | Used to treat psoriasis | [27] |

| Chilli | |||

| Family Solanaceae | |||

| 11 | Dalbergia sissoo | Used to treat abscesses | [28] |

| North Indian rosewood | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 12 | Eucalyptus globulus | Used to treat acne, fungal infections, and heal wounds | [29] |

| Eucalyptus | |||

| Family Myrtaceae | |||

| 13 | Euphorbia wallichii | Used to treat skin infections and warts | [30] |

| Wallich spurge | |||

| Family Euphorbiaceae | |||

| 14 | Ficus carica | Used to treat itching, pimples, and scabies | [31] |

| Fig | |||

| Family Moraceae | |||

| 15 | Fagopyrum tataricum | Used to treat erysipelas | [32] |

| Tartary buckwheat | |||

| Family Polygonaceae | |||

| 16 | Gnaphalium affine | Used to treat weeping pruritus of skin | [33] |

| Cotton weed | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 17 | Juniperus excelsa | Used to treat skin infections | [34] |

| Eastern savin | |||

| Family Cupressaceae | |||

| 18 | Lens culinaris | Used to treat skin infections and acne | [35] |

| Lentil | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 19 | Marsilea quadrifolia | Used to treat abscesses | [36] |

| Water clover | |||

| Family Marsileaceae | |||

| 20 | Mahonia aquifolium | Used to treat psoriasis | [37] |

| Oregon grape | |||

| Family Berberidaceae | |||

| 21 | Pleurospermum brunonis | Used to treat skin infections | [38] |

| Brown’s paper cup flower | |||

| Family Apiaceae | |||

| 22 | Pinus roxburghii | Used to treat pruritus, inflammation, and other skin diseases | [39] |

| Chir pine | |||

| Family Pinaceae | |||

| 23 | Pinus wallichiana | Used to treat wound infection | [40] |

| Bhutan pine | |||

| Family Pinaceae | |||

| 24 | Rubia cordifolia | Used to treat psoriasis | [41] |

| Common madder | |||

| Family Rubiaceae | |||

| 25 | Solanum nigrum | Used to treat pimples, pustules, ringworms, eczema, syphilitic ulcers, and leukoderma | [42,43] |

| Black nightshade | |||

| Family Solanaceae | |||

| 26 | Simmondsia chinensis | Used to treat acne and psoriasis | [44] |

| Jojoba | |||

| Family Buxaceae | |||

| 27 | Taxus wallichiana | Used to treat psoriasis and ringworm | [45] |

| Himalayan yew | |||

| Family Taxaceae | |||

| 28 | Tectona grandis | Used to treat pruritus and heal wounds | [46,47] |

| Teak | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 29 | Thespesia populne | Used to treat psoriasis | [48] |

| Indian tulip tree | |||

| Family Malvaceae | |||

| 30 | Wrightia tinctoria | Used to treat psoriasis | [49] |

| Sweet indrajao | |||

| Family Apocynaceae | |||

| B | Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Eczema | ||

| 31 | Abrus precatorious | Used to treat eczema | [50] |

| Rosary pea | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 32 | Avena sativa | Used to treat eczema, wounds, inflammation, itching, burns, and irritation | [51] |

| Oat | |||

| Family Poaceae | |||

| 33 | Arnebia euchroma | Used to treat burns, eczema, and dermatitis | [52,53] |

| Pink arnebia | |||

| Family Boraginaceae | |||

| 34 | Actinidia deliciosa | Used to treat inflammation and eczema | [54] |

| Kiwi fruit | |||

| Family Actinidiaceae | |||

| 35 | Aristolochia indica | Used to treat eczema and wounds | [55] |

| Indian birthwort | |||

| Family Aristolochiaceae | |||

| 36 | Betula alba | Used to treat eczema, psoriasis, and acne | [56] |

| Paper birch | |||

| Family Betulaceae | |||

| 37 | Cannabis sativus | Used to treat sores, eczema, dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic, and lichen planus | [57] |

| Charas, ganja | |||

| Family Cannabaceae | |||

| 38 | Matricaria chamomilla | Used to treat eczema and skin inflammation | [58,59] |

| Chamomile | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 39 | Sarco asoca | Used to treat skin diseases, inflammation, eczema, and scabies | [60] |

| Ashoka | |||

| Family Caesalpiniaceae | |||

| 40 | Saponaria officinalis | Used to treat eczema, acne, boils, and psoriasis | [61,62] |

| soapworts | |||

| Family Caryophyllaceae | |||

| 41 | Vitex negundo | Used to treat skin diseases such as eczema, acne, pimples, ringworms, etc. | [35] |

| Nirgundi | |||

| Family Verbenaceae | |||

| C | Medicinal Plants Used for Wound healing | ||

| 42 | Achillea millefolium | Used to treat burn wounds | [63] |

| Common Yarrow | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 43 | Albizia lebbeck | Used for wound healing, leucoderma, itching, and inflammation | [64] |

| Siris | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 44 | Allium sativum | Used to treat psoriasis, scars, and heal wounds | [65] |

| Garlic | |||

| Family Alliaceae | |||

| 45 | Aloe barbadensis | Used to treat skin injuries | [66] |

| Aloe vera | |||

| Family Aloeaceae | |||

| 46 | Alternanthera brasiliana | Used to heal inflammation wounds | [64] |

| Brazilian joyweed | |||

| Family Amaranthaceae | |||

| 47 | Abelmoschus esculentus | Used to cure pimples and wounds | [67] |

| Okra | |||

| Family Malvaceae | |||

| 48 | Adiantum venustum D | Used to heal wounds | [68] |

| Himalayan maidenhair | |||

| Family Pteridaceae | |||

| 49 | Argemone Mexicana | Used to treat wounds | [69] |

| Mexican poppy | |||

| Family Papaveraceae | |||

| 50 | Alkanna tinctoria | Used to treat itching, skin wounds, and rashes | [70] |

| Alkanet | |||

| Family Boraginaceae | |||

| 51 | Brassica oleracea | Used to treat dermatitis and wounds | [71] |

| Red cabbage | |||

| Family Brassicaceae | |||

| 52 | Berberis lycium | Used to heal wounds | [72] |

| Indian lycium | |||

| Family Berberidaceae | |||

| 53 | Bergenia ciliata | Used to heal wounds | [73,74] |

| Winter begonia | |||

| Family Saxifragaceae | |||

| 54 | Bergenia ligulata | Used to heal wounds and treat boils | [75] |

| Asmabhedaka | |||

| Family Saxifragaceae | |||

| 55 | Bauhinia purpurea | Used to heal wounds and treat inflammation | [76] |

| Orchid tree | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 56 | Carissa spinarum | Used to heal wounds and treat boils | [77] |

| Bush plum | |||

| Family Apocynaceae | |||

| 57 | Cannabis sativa | Used to treat dandruff and heal wounds | [78] |

| Marijuana, hemp | |||

| Family Cannabaceae | |||

| 58 | Capparis decidua | Used to heal wounds | [79] |

| Bare caper | |||

| Family Capparaceae | |||

| 59 | Cynodon dactylon | Used to heal wounds and skin problems | [80,81] |

| Bermuda grass | |||

| Family Poaceae | |||

| 60 | Cocos nucifera | Used to treat skin wounds | [82] |

| Coconut | |||

| Family Arecaceae | |||

| 61 | Euphorbia helioscopia | Used to heal wounds | [83,84] |

| Sun spurge | |||

| Family Euphorbiaceae | |||

| 62 | Ferula foetida | Used to heal wounds | [85] |

| Asafoetida, Hing | |||

| Family Apiaceae | |||

| 63 | Ficus benghalensis | Used to treat skin injuries | [86] |

| Banyan tree | |||

| Family Moraceae | |||

| 64 | Gerbera gossypina | Used to heal wounds | [87] |

| Hairy gerbera daisy | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 65 | Galium aparine | Used to treat wounds as an antiseptic | [88] |

| Goosegrass | |||

| Family Rubiaceae | |||

| 66 | Hackelia americana | Used to treat wounds, tumors, and inflammation | [89] |

| Nodding stickseed | |||

| Family Boraginaceae | |||

| 67 | Hypericum perforatum | Used to treat wounds, abrasions, inflammatory skin disease, and burns | [90] |

| Perforatejohn’s wort | |||

| Family Hypericaceae | |||

| 68 | Isodon rugosus | Used to heal wounds | [91] |

| Wrinkled leaf isodon | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 69 | Launaea nudicaulis | Used to heal wounds | [92] |

| Bhatal | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 70 | Momordica charantia | Used to heal wounds | [93] |

| Bitter gourd | |||

| Family Cucurbitaceae | |||

| 71 | Micromeria biflora | Used to heal wounds and treat skin infections | [94] |

| Lemon savory | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 72 | Nigella sativa | Used to heal wounds | [95,96] |

| Black cumin | |||

| Family Ranunculaceae | |||

| 73 | Plantago major | Used to treat wounds | [97] |

| Great plantain | |||

| Family Plantaginaceae | |||

| 74 | Plantago lanceolata | Used to heal wounds | [98] |

| Ribwort plantain | |||

| Family Plantaginaceae | |||

| 75 | Rumex dissectus | Used to stop wound bleeding | [99] |

| Arrowleaf dock | |||

| Family Polygonaceae | |||

| 76 | Salvia moorcroftiana | Used to treat skin itching and wound healing | [100] |

| Kashmir salvia | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 77 | Trigonella foenum-graecum | Used to heal wounds | [101,102] |

| Fenugreek | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 78 | Tephrosia purpurea | Used to heal wounds | [103] |

| Wild indigo | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 79 | Urtica dioica | Used to heal wounds | [104,105] |

| Stinging nettle | |||

| Family Urticaceae | |||

| 80 | Verbascum Thapsus | Used to treat pimples, heal wounds, and treat other skin problems | [106] |

| Common mullein | |||

| Family Scrophulariaceae | |||

| D | Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Skin Burns | ||

| 81 | Astilbe thunbergii | Used to treat burns | [107] |

| Astilbe | |||

| Family Saxifragaceae | |||

| 82 | Anaphalis margaritacea | Used to treat sunburn | [108] |

| Pearly everlasting | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 83 | Aquilegia pubiflora | Used to heal wounds and treat skin burns | [109] |

| Himalayan columbine | |||

| Family Ranunculaceae | |||

| 84 | Amygdalus communis | Used to treat burn wounds | [53] |

| Almonds | |||

| Family Rosaceae | |||

| 85 | Bergenia stracheyi | Used to treat sunstroke and heal wounds | [110] |

| Himalayan Bergenia | |||

| Family Saxifragaceae | |||

| 86 | Calendula officinalis | Used to treat burns and bruises | [111] |

| Marigold | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 87 | Cucumis melo | Used to treat skin burns | [112] |

| Muskmelon | |||

| Family Cucurbitaceae | |||

| 88 | Corydalis govaniana | Used to treat skin burns | [113] |

| Govan’s corydalis | |||

| Family Papaveraceae | |||

| 89 | Carica candamarcensis | Used to treat burn wounds | [114] |

| Mountain papaya | |||

| Family Caricaceae | |||

| 90 | Clitoria ternatea | Used to treat boils, acne, and skin outbreaks | [115] |

| Butterfly pea | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 91 | Datura stramonium | Used to treat boils | [116] |

| Jimsonweed, thornapple | |||

| Family Solanaceae | |||

| 92 | Dodonaea viscosa | Used to treat skin burns and heal wounds, acne, pimples, rashes, itching, and pustules | [117,118,119] |

| Hop bush | |||

| Family Sapindaceae | |||

| 93 | Echinacea angustifolia | Used to treat psoriasis, burns, acne, ulcers, and skin wounds | [120] |

| Purple coneflower | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 94 | Ginkgo biloba | Used to treat skin burns | [121] |

| Maidenhair tree | |||

| Family Ginkgoaceae | |||

| 95 | Hippophae rhamnoides | Used to treat rashes and skin burns | [122,123] |

| Sea buckthorn | |||

| Family Elaeagnaceae | |||

| 96 | Impatiens edgeworthii | Used to treat skin burns | [124] |

| Edgeworth Balsam | |||

| Family Balsaminaceae | |||

| 97 | Mangifera indica | Protect skin from sun damage | [125] |

| Mango | |||

| Family Anacardiaceae | |||

| 98 | Malus pumila | Used to treat boils | [126] |

| Apple | |||

| Family Rosaceae | |||

| 99 | Malva sylvestris | Used to treat burn wounds | [53] |

| High mallow | |||

| Family Malvaceae | |||

| 100 | Matricaria chamomilla | Used to treat burn wounds | [127] |

| Chamomile | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 101 | Onosma hispida | Used to treat skin burns | [128] |

| Bristly onosma | |||

| Family Boraginaceae | |||

| 102 | Portulaca oleracea | Used to treat burns, skin eruptions, rashes, skin inflammation, eczema, abscesses, and pruritus | [129,130,131] |

| Purslane, little hogweed | |||

| Family Portulacaceae | |||

| 103 | Pisum sativum | Used to treat skin burns | [132] |

| Garden pea | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 104 | Picrorhiza kurroa | Used to treat burning sensation | [133] |

| Kutki | |||

| Family Plantaginaceae | |||

| 105 | Rumex dentatus | Used to treat boils | [134] |

| Toothed dock | |||

| Family Polygonaceae | |||

| 106 | Rubus abchaziensis | Used to treat boils and wounds | [135] |

| Akhray | |||

| Family Rosaceae | |||

| 107 | Solanum virginianum | Used to treat swelling of skin | [136] |

| Thorny nightshade | |||

| Family Solanaceae | |||

| 108 | Scrophularia deserti | Used to treat burn wounds | [53] |

| Desert figwort | |||

| Family Scrophulariaceae | |||

| 109 | Sesamum indicum | Used to treat burn wounds | [137] |

| Sesame | |||

| Family Pedaliaceae | |||

| 110 | Silybum marianum | Used to treat burn wounds and improve skin health | [138] |

| Blessed thistle | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 111 | Tamarix aphylla | Used to treat skin burns and wounds | [139] |

| Athel | |||

| Family Tamaricaceae | |||

| 112 | Tridax procumbens | Used to treat burn wounds | [140] |

| Coatbuttons, tridax daisy | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 113 | Zanthoxylum armatum | Used to treat skin burns | [141] |

| Winged prickly ash | |||

| Family Rutaceae | |||

| E | Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Miscellaneous Disorders | ||

| 114 | Allium cepa | Used to treat skin lesions | [142] |

| Garden onion | |||

| Family Alliaceae | |||

| 115 | Azadirachta indica | Used to treat acne and protect skin from UV rays | [143] |

| Neem | |||

| Family Meliaceae | |||

| 116 | Anethum graveolens | Used to treat pimples | [144] |

| Dill | |||

| Family Apiaceae | |||

| 117 | Androsace rotundifolia lehm. | Used to treat skin problems | [145] |

| Rock jasmine | |||

| Family Primulaceae | |||

| 118 | Arnica montana | Used as anti-inflammatory to treat boils and acne eruptions | [146,147] |

| Mountain arnica | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 119 | Bauhinia variegata | Used to treat skin disease and skin ulcers | [148] |

| Kachnar, orchid tree | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 120 | Beta vulgaris | Used to treat tumors | [149] |

| Beetroot | |||

| Family Brassicaceae | |||

| 121 | Brassica juncea | Used against skin eruptions and ulcers | [150,151] |

| Mustard | |||

| Family Brassicaceae | |||

| 122 | Berberis aquifolium | Used to treat acne scars | [152] |

| Oregon grape | |||

| Family Berberidaceae | |||

| 123 | Camellia sinensis | Used to treat skin tumors and cancer | [153] |

| Green Tea | |||

| Family Theaceae | |||

| 124 | Coriandrum sativum | Used to treat pimples | [154,155] |

| Dhaniya | |||

| Family Apiaceae | |||

| 125 | Calotropis procera | Used to treat inflammation | [156] |

| Giant milkweed | |||

| Family Apocynaceae | |||

| 126 | Cerastium fontanum | Used to treat skin diseases; also acts as anti-inflammatory | [157] |

| Mouse ear chickweed | |||

| Family Caryophyllaceae | |||

| 127 | Citrus medica | Used to treat skin irritation | [158,159] |

| Citron | |||

| Family Rutaceae | |||

| 128 | Citrus sinensis | Used to treat pimples | [160] |

| orange | |||

| Family Rutaceae | |||

| 129 | Catharanthus roseus | Used to cure pimples | [161] |

| Periwinkle | |||

| Family Apocynaceae | |||

| 130 | Carthamus tinctorius | Used to treat eruptive skin problems | [162] |

| safflower | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 131 | Clerodendrum viscosum | Used as antiseptic skin wash | [163] |

| Hill glory bower | |||

| Family Verbenaceae | |||

| 132 | Equisetum arvense | Used to treat skin allergy | [164] |

| Field horsetail | |||

| Family Equisetaceae | |||

| 133 | Lavendula officinalis | Used to prevent and heal acne | [165] |

| Lavender | |||

| Family Labiatae | |||

| 134 | Lawsonia inermis | Used to treat inflammation and tumors | [166] |

| Henna | |||

| Family Lythraceae | |||

| 135 | Lycopersicon esculentum | Used to treat acne and sunburn | [167] |

| Tomato | |||

| Family Solanaceae | |||

| 136 | Ledum groenlandicum oedar | Used to treat itching, acne, and redness | [61] |

| Labrador tea | |||

| Family Ericaceae | |||

| 137 | Mirabilis jalapa | Used to treat allergic skin disorders | [168] |

| Four o’clock | |||

| Family Nyctaginaceae | |||

| 138 | Melia azedarach | Used to treat pimples and inflammation | [169] |

| Persian lilac | |||

| Family Meliaceae | |||

| 139 | Myrsine Africana | Used to treat skin disorders | [170] |

| Cape myrtle | |||

| Family Myrsinaceae | |||

| 140 | Melaleuca alternifolia | Used to treat acne | [171] |

| Tea tree | |||

| Family Myrtaceae | |||

| 141 | Olea europaea | Used as skin cleanser | [172] |

| Olive tree | |||

| Family Oleaceae | |||

| 142 | Ocimum sanctum | Used to treat acne and inflammation | [173,174] |

| Tulsi | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 143 | Plumbago zeylanica | Used to treat skin diseases such as sores, acne, and dermatitis | [31] |

| Doctor bush | |||

| Family Plumbaginaceae | |||

| 144 | Prunus persica | Used to treat skin disorders | [175] |

| Peach | |||

| Family Rosaceae | |||

| 145 | Piper nigrum | Used to treat acne | [176] |

| Black pepper | |||

| Family Piperaceae | |||

| 146 | Pterocarpus santalinus | Used to treat skin inflammation and acne | [177] |

| Red sandalwood | |||

| Family Fabaceae | |||

| 147 | Rosmarinus officinalis | Used to block skin tumor cells | [178] |

| Rosemary | |||

| Family Lamiaceae | |||

| 148 | Ricinus communis | Used in children for skin diseases | [179] |

| Castor oil plant | |||

| Family Euphorbiaceae | |||

| 149 | Rheum officinale | Used to treat acne | [180] |

| Rhubarb | |||

| Family Polygonaceae | |||

| 150 | Salix babylonica | Used as skin cleanser | [181] |

| Weeping willow | |||

| Family Salicaceae | |||

| 151 | Serenoa repens | Used to treat acne and inflammation | [182] |

| Saw palmetto | |||

| Family Arecaceae | |||

| 152 | Thymus vulgaris | Used to treat cellulitis | [153] |

| Thyme | |||

| Family a | |||

| 153 | Taraxacum officinale | Used to treat pimples | [183] |

| Common dandelion | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 154 | Tussilago farfara | Used to treat sores and inflammation of skin | [184] |

| coltsfoot | |||

| Family Asteraceae | |||

| 155 | Valeriana jatamansi | Used to treat pimples | [185] |

| Jatamansi | |||

| Family Caprifoliaceae | |||

3. Some Reported Mechanism of Action

The use of herbal medicine is becoming popular worldwide. Herbal medicines are preferred over synthetic medicines, as they produce fewer side effects [186,187,188,189]. Additionally, phytochemicals can treat skin ailments by different mechanisms and by displaying various biological activities such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic [190,191,192]. Each plant has its own bioactivity, which depends upon the chemical nature and potency of the constituents present in it [193,194]. Some components reduce skin inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB, for example, Zingiber officinale. The squeezed extract of this in rats and mice elevates TNF-α in peritoneal cells, and its long-term use can increase the level of serum corticosterone and thus reduce proinflammatory markers [195]. Drugs such as Rosmarisum officinalis also help in the improvement of abnormal skin conditions. It constitutes rosmarinic acid, which can disturb the system activation inhibition of the C3b attachment. It also acts on the inhibition and reduction of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-1 [196]. Oenothera biennis constitutes β-sitosterol, which modulates NO, TNF-α, IL-, and TXB2, leading to the suppression of COX-2 gene expression, hence causing anti-inflammatory action [197].

4. FDA-Approved Formulas

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as in vitro and in vivo study results, has approved bacterial cellulose (BC) and plant cellulose (PC) products to be incorporated into the biomedical field and their applications due to their biocompatibility with human cells and potential activity in wound healing and in the therapeutics field [198].

Moreover, honey, a natural product, is rich in several phenolic compounds, sugars, and enzymes that possess antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activity. The main role of honey in the development of the wound healing process appeared to be via the acceleration of dermal repair and epithelialization, angiogenesis promotion, immune response promotion, and the reduction in healing-related infections with pathogenic microorganisms. The FDA approved many formulas containing honey as the main ingredient, among which is L-Mesitran® (manufactured by Triticum Company—UK) Ointment, which consists of 48% medical-grade honey, lanolin, cod liver oil, sunflower oil, calendula, aloe vera, zinc oxide, and vitamins C and E. Additionally, Revamil Gel® (manufactured by Maximed Pharrma—Lebanon) was FDA approved, containing 100% medical-grade honey, together with Therahoney® Gel (manufactured by Medline Industries Inc.—USA), containing 100% Manuka honey [199].

5. Phytoconstituents of Medicinal Plants

Many phytochemical constituents have shown potential bioactivities, to which the biological activities of medicinal plant extracts can be attributed. Table 2 summarizes some of them in the context of treating skin disorders.

Table 2.

Selected reported phytoconstituents of herbal plants used to treat skin diseases.

| Serial No. | Botanical Name | Some Phytoconstituents and/or Classes ofCompounds | Selected Structures | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Abrus precatorious | Stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, and abrusogenin | Abrusogenin

|

[200] |

| 2. | Achillea millefolium | Chlorogenic acid, apigenin-7-glucoside, and luteolin-7-glucoside | Chlorogenic acid

|

[201] |

| 3. | Achyranthes aspera | Rutin, chlorogenic acid, and genistein | Genistein

|

[202] |

| 4. | Allium cepa | Quercetin, S-methyl-L-cysteine, cycloalliin, N-acetylcysteine, S-propyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide, and dimethyl trisulfide | Cycloalliin N-acetyl cysteine  S-methyl-L-cysteine

|

[203] |

| 5. | Azadirachta indica | Nimbin, nimbanene, ascorbic acid, n-hexacosanol, nimbolide, 17-hydroxy azadiradione, 6-desacetyl nimbinene, and nimbandiol | Nimbin

|

[204] |

| 6. | Albizia lebbeck | Lupeol, lupenone, luteolin, rutin, sapiol, friedelin, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol-3-glucoside, β-sitosterol-3-glucoside, alkaloids as 3,3-dimethyl-4-(1-aminoethyl)-azetidin-2-one, 2-amino-4-hydroxy pteridine-6-carboxylic acid, and 2,4 bis(hydroxylamino)-5-nitropyrimidine | Lupeol

|

[205] |

| 7. | Allium sativum | Alliin, allicin, S-allyl cysteine, diallyl sulfide, diallyl trisulfide, diallyl disulfide, and ajoene | Alliin

|

[206] |

| 8. | Aloe barbadensis | Aloesin, cinnamic acid, isoaloresin D, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, aloin A and B, emodin, isovitexin, and orientin | Aloin

|

[207] |

| 9. | Alternanthea brasiliana | Amaranthine, iso amaranthine, betanin, isobetanin, hydroxybenzoic acid, hydroxycinnamic acid, kaempferol glucoside, rhamnoside, and dirhamnosyl-glucoside | Amaranthine

|

[208] |

| 10. | Anethumgraveolens | Limonene, carvone, α-phellandrene, β-phellandrene, and p-cymene | Limonene

|

[209] |

| 11. | Avena sativa | Proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, β-glycan, dietary fibers, avenanthramides, gramine alkaloid, flavonolignans, flavonoids, saponins, and sterols | Avenanthramide A

|

[210] |

| 12. | Arnebia euchroma | Shikonin, methyllasiodiplodin, euchroquinols A-C, and 9,17-epoxy arnebinol | Shikonin,

|

[211] |

| 13. | Astilbe thunbergii | Eucryphin, astilbin, and berginin | Eucryphin

|

[107] |

| 14. | Actinidia deliciosa | Rutin, quercitrin, quercetin, chrysin, and syringic acid | Quercetin

|

[212] |

| 15. | Anaphalis margaritacea | Volatile oil contains E-caryophyllene, and its oxide, δ-cadinene, γ-cadinene, cubenol, ledol, and α-pinene | E-caryophyllene

|

[213] |

| 16. | Abelmoschus esculentus | Quercetin-3-glucoside, diglucoside, catechins, and hydroxyl cinnamic acid derivatives | Quercetin-3-glucoside

|

[214] |

| 17. | Adiantum venustum Don | Norlupane, noroleanane, lupane triterpenoids, adiantone, and 21-hydroxyadiantone (Norhopane)triterpenes | Adiantone

|

[215] |

| 18. | Saponaria officinalis | Saponins | Cyclamin

|

[62] |

| 19. | Aquilegia pubiflora | Orientin, coumaric acid, sinapic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, vitexin, isoorientin, and isovitexin | Orientin

|

[216] |

| 20. | Argemone mexicana | Berberine, oxyberberine, arginine, higenamine, pancorine, sanguinarine, β-amyrin, trans-phytol, luteolin, quercetin, quercitrin, and rutin | Berberine

|

[69] |

| 21. | Arnica montana | Sesquiterpene lactones, phenolic acids, flavonoids, helenalin, acetyl helenalin, metacryl helenalin, chlorogenic acid, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 4,5- dicaffeoylquinic acid, quercetin-3-glucoside, quercetin-3-glucuronide, kaempferol-3-glucoside, and kaempferol-3-glucuronide | Solaniol

|

[217] |

| 22. | Alkanna tinctoria | Alkaloid, bufadienolides, carbohydrate, flavonoids, saponins, and tannins | Bufadienolide

|

[218] |

6. Computational Studies

6.1. Methodology of Molecular Docking Studies

Based on the aforementioned, human granzyme B in complex with 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-beta-D-glucopyranose [219] was downloaded from PDB (Code: 1IAU), while the crystal structure of highly glycosylated human leukocyte elastase in complex with a thiazolidinedione inhibitor (5-[[4-[[(2~{S})-4-methyl-1-oxidanylidene-1-[(2-propylphenyl)amino]pentan-2-yl]carbamoyl]phenyl]methyl]-2-oxidanylidene-1,3-thiazol-1-ium-4-olate) [220] was also downloaded from PDB (Code: 6F5M). Both enzymes were cleaned for missing amino acids or gaps in their sequences. Hydrogens were added, water molecules were removed if present, and simulation for forcefield CHARMm and partial charge MMFF was applied. A heavy atom was built, and fixation of atom constraints was applied before enzyme minimization. The receptor was identified, and the binding site was highlighted from the complexed ligand, which was later cut off for the comparative docking study. The structures of the selected active constituents were downloaded from PubChem with the .svd extension and opened in the program. A simulation for all selected 23 active constituents was applied with the CHARMm forcefield and partial charge MMFF, and ligand preparation was carried out. The 23 resulting compounds, together with the reference ligand, were allowed to dock against both enzymes using the C-docker protocol.

6.2. Results and Discussion of Computational Studies

Molecular docking is of great importance for illustrating the molecular interactions of natural compounds with different receptors [221]. Although each docking program operates slightly differently, they share common features that involve ligand and receptor, sampling, and scoring. Thus, a molecular docking study was performed using the selected software Discovery Studio 4.1 [222,223,224]. Twenty-three interesting phytoconstituents of the previously detailed plants were selected for in silico docking trials to explore their activity and possible mechanism of binding against two essential enzymes human granzyme B and human leukocyte elastase, where the inhibition of either or both of those enzymes could aid in the treatment of various skin diseases.

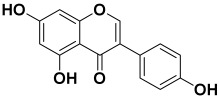

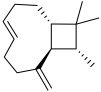

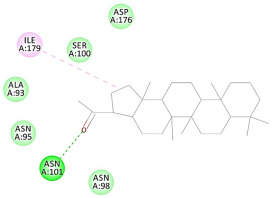

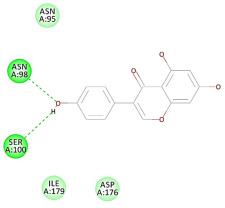

The 2D interaction energy of the 23 active constituents compared to the reference ligand 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-beta-D-glucopyranose, together with their C-docker interaction energy, is displayed in Table 3. The ligand displayed –27.55 Kcal/mol, saponin showed –28.10 Kcal/mol, and the rest of the constituents showed –21.42 to –1.05 Kcal/mol. Both S-methyl-L-cysteine and N-acetyl cysteine were unsuccessful in the inhibition of granzyme B. The reference ligand performed its inhibitory action via four H-bonds with essential amino acids in the granzyme B sequence (Ala 93, Asn 98, Tyr 175, and Asp 176) and via van der Waals forces with six other amino acids (Asn 95, Ser 100, Asn 101, Ser 177, Thr 178, and Ile 179). Saponin was the only constituent better than the inhibitor, displaying better interaction energy and binding mode comparable to the ligand, as shown in Figure 1. Cyclamin saponin bounded by two H-bonds with Ser 100 and three H-bonds with Asn 101, Asp 176, and Thr178, while it displayed van der Waals force attractions with Asn 93, Asn 95, Asn 98, and Ile 179.

Table 3.

Results of molecular modeling study of 24 active constituents against human granzyme B (1IAU) compared to reference complexed ligand.

| Serial No. | Compound | (C-Docker Interaction Energy) | 2D Interaction Diagram * | Type of Binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ligand (reference) | −27.55 |

|

H-bond: Ala 93, Asn 98, Asp 176, Tyr 175 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Ser 100, Asn 101, Ser 177, Thr 178, Ile 179 |

| 2 | Cyclamin (saponin) | −28.10 |

|

H-bond: Ser 100 (×2), Asn 101, Asp 176, Thr 178 Van der Waals: Asn 93, Asn 95, Asn 98, Ile 179 |

| 3 | Amaranthine | −21.42 |

|

H-bond: Asn 95, Asn 98, His 173 (×2) Pi-Pi: Tyr 174 Van der Waals:Lys 97 |

| 4 | Alliin | −18.53 |

|

H-bond: Ser 100 (×2) Pi-Pi: Asp 176 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Asn 98, Asn 101, Ile 179 Unfavorable: Asp 176 |

| 5 | Quercetin-3-glucoside | −17.59 |

|

H-bond: Asn 95, Asp 176, Thr 178 Van der Waals: Asn 98, Ile 179 |

| 6 | Aloin | −17.35 |

|

H-bond: Ser 100, Asp 176 (×2) Van der Waals: Asn 95, Asn 98, Asn 101, Thr 178, Ile 179 |

| 7 | Berberine | −15.12 |

|

Pi-Pi: Asp 176 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Asn 98, Ser 100, Ile 179 |

| 8 | Chlorogenic acid | −14.09 |

|

H-bond: Asp 176, Thr 178 (×2) Van der Waals: Ile 179 |

| 9 | Avenanthramide A | −14.03 |

|

H-bond: Asn 95, Asn 98, Asp 176 Van der Waals: Ser 100, Ile 179 |

| 10 | Adiantone | −12.76 |

|

H-bond: Asn 101 Pi-Alkyl: Ile 179 Van der Waals: Ala 93, Asn 95, Asn 98, Ser 100, Asp 176 |

| 11 | Orientin | −11.89 |

|

H-bond: Asn 98, Ser 100, Asp 176 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Ile 179 |

| 12 | Eucryphin | −11.34 |

|

H-bond: Ala 93, Ser 100 Van der Waals: Tyr 94, Asn 95, Asn 98, Ser 100, Asn 101 |

| 13 | Lupeol | −11.15 |

|

Van der Waals: Ala 93, Asn 95, Asn 98, Ser 100, Asn 101, Asp 176, Ile 179 |

| 14 | Quercetin | −11.02 |

|

H-bond: Asn 98, Ser 100, Asp 176 Van der Waals: Ile 179 |

| 15 | Abrusogenin | −10.47 |

|

H-bond:Asn 95, Asn 98 |

| 16 | Shikonin | −10.25 |

|

H-bond: Asn 95, Asn 101 Van der Waals: Ala 93, Asn 98, Ser 100 |

| 17 | Bufadienolide | −10.05 |

|

Pi-Alkyl: Ile 179 Van der Waals: Ala 93, Asn 98, Ser 100, Asn 101, Asp 176, Thr 178 |

| 18 | Nimbin | −8.77 |

|

H-bond: Ser 100 (×2), Asp 176 (×2) Van der Waals: Asn 95, Asn 98, Thr 178, Ile 179 |

| 19 | Genistein | −7.64 |

|

H-bond: Asn 98, Ser 100 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Asp 176, Ile 179 |

| 20 | Solaniol | −7.28 |

|

H-bond: Asn 98 Van der Waals: Asn 95, Ser 100, Asn 101, Asp 176, Ile 179 |

| 21 | E-caryophyllene | −3.25 |

|

Van der Waals: Asn 98, Ser 100, Asn 101, Asp 176, Ile 179 |

| 22 | Limonene | −2.48 |

|

Van der Waals: Asn 98, Ser 100, Asp 176, Ile 179 |

| 23 | S-methyl-L-cysteine | −1.79 | No interaction | |

| 24 | N-acetyl cysteine | −1.05 | No interaction |

* Color reference: green dotted line indicates H-bond; faint green dotted line indicates van der Waals interaction; orange dotted line indicates Pi-Pi bond; red dotted line indicates unfavorable interaction; purple dotted line indicates Pi-alkyl bond.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional (3D) interaction diagram of cyclamin (saponin) against human granzyme B (1IAU).

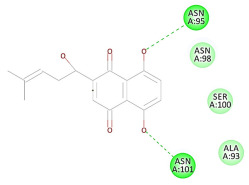

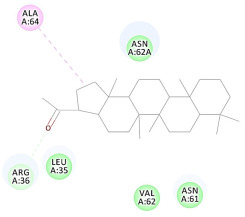

The results of the docking study against human leukocyte elastase are presented in Table 4. It is shown that the reference complexed thiazolidinedione inhibitor displayed C-docker interaction energy equivalent to −33.57 Kcal/mol, while both constituents saponin and amaranthine displayed −48.50 and −47.62 Kcal/mol, respectively. The rest of the compounds displayed in the range of –28.97−10.60 Kcal/mol. The thiazolidinedione ligand inhibited the elastase via four essential H-bonds (Val 59, Asn 61, Asn 62A, and Val 62) and Pi-Pi bonding with Leu 35, Val 62B, and Ala 64. The van der Waals interaction was with Arg 36, Ala 60, and Ile 88. Comparably, saponin was able to inhibit elastase in the same mode, as shown in Figure 2, with better interaction energy. Cyclamin (saponin) bounded to the strategic binding site via two H-bonds with Ala 60 and two H-bonds with Asn 61 and Arg 63, Pi—Pi- bonds with Leu 35, and van der Waals interaction with Arg 36, Gly 39, His 40, Val 59, Val 62, Asn 62 Chain A, Val 62 Chain B, Ile 88, and Glu 90. On the other hand, amaranthine bounded to the binding site via three H-bonds with Ala 60, Asn 61, and Val 62, attractive charge with Arg 36, and van der Waals forces with Leu 35, Val 59, Asn 62 Chain A, and Val 62 Chain B.

Table 4.

Results of molecular modeling study of 23 active constituents against human leukocyte elastase (6F5M) compared to reference complexed ligand.

| Serial No. | Compound | (C-Docker Interaction Energy) | 2D Interaction Diagram * | Type of Binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ligand (reference) | −33.57 |

|

H-bond: Val 59, Asn 61, Asn 62A, Val 62 Pi-Pi bond: Leu 35, Val 62B, Ala 64 Van der Waals: Arg 36, Ala 60, Ile 88 |

| 2 | Cyclamin (Saponin) | −48.50 |

|

H-bond: Ala 60(×2), Asn 61, Arg 63 Pi-Pi bond: Leu 35 Van der Waals: Arg 36, Gly 39, His 40, Val 59, Val 62, Asn 62A, Val 62B, Ile 88, Glu 90 |

| 3 | Amaranthine | −47.62 |

|

H-bond: Ala 60, Asn 61, Val 62 Attractive charge: Arg 36(×2) Van der Waals: Leu 35, Val 59, Asn 62A, Val 62B |

| 4 | Chlorogenic acid | −28.97 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Asn 62A, Glu 90 Pi-sigma: Ala 60 Van der Waals: Val 59, Val 62, Val 62B, Ile 88, Tyr 94 |

| 5 | Quercetin-3-glucoside | −27.94 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Asn 62A Pi-lone pair: Asn 61 Pi-Pi: Val 62 Van der Waals: Leu 35, Val 62B |

| 6 | Orientin | −26.43 |

|

H-bond: Val 59, Asn 61(×2), Asn 62A, Val 62 Pi-Pi: Val 62 Pi-alkyl: Val 62B Van der Waals: Leu 35, Ala 60 |

| 7 | Abrusogenin | −26.39 |

|

H-bond: Asn 62A, Val 62B Pi-alkyl: Val 62B Van der waal: Leu 35, Arg 36, Ala 60, Asn 61 |

| 8 | Alloin | −24.93 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A(×2) Pi-amide: Val 62 Van der Waals: Leu 35, Val 59, Ala 60, Val 62B |

| 9 | Avenanthramide A | −24.18 |

|

H-bond: Val 62B Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60, Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A, Arg 63, Ile 88 |

| 10 | Nimbin | −22.68 |

|

H-bond: Val 62, Asn 62A(×2), Val 62B Pi-Alkyl: Val 62B Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60, Asn 61, Arg 63 |

| 11 | Eucryphin | −22.47 |

|

H-bond: Ala 60, Asn 62A Pi-lone pair: Asn 61 Pi-alkyl: Val 62 Van der Waals: Leu 35, Val 62B |

| 12 | Quercetin | −20.25 |

|

H-bond: Ala 60, Asn 61, Asn 62A Pi-amide: Val 62 Van der Waals: Val 62B, Ile 88 |

| 13 | Shikonin | −19.80 |

|

H-bond: Val 59, Asn 61, Val 62B Pi-sigma: Asn 62A Pi-amide: Val 62 Van der Waals: Ala 60, Ile 88 |

| 14 | Bufadienolide | −18.71 |

|

H-bond: Arg 36 Pi-alkyl: Leu 35(×2), Val 62 Van der Waals: Asn 61, Asn 62A |

| 15 | Genistein | −18.31 |

|

H-bond: Asn 62A Pi-lone pair: Asn 61 Pi-amide: Val 62 Pi-alkyl: Val 62B Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60 |

| 16 | Lupeol | −18.19 |

|

H-bond: Ala 60 Van der waal: Leu 35, Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A, Val 62B |

| 17 | Adiantone | −17.99 |

|

H-bond: Arg 36 Pi-alkyl: Ala 64 Van der Waals: Leu 35, Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A |

| 18 | Solaniol | −17.44 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Asn 62A, Val 62 Van der Waals: Ala 60, Val 62B |

| 19 | N-acetyl cysteine | −17.25 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Asn 62A (×3) Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60, Val 62, Val 62B |

| 20 | Berberine | −16.59 |

|

H-bond: Val 59, Asn 61, Val 62B Van der Waals: Ala 60, Val 62, Asn 62A |

| 21 | Alliin | −15.63 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60, Val 62B |

| 22 | S-methyl-L-cysteine | −14.29 |

|

H-bond: Asn 61, Asn 62A, Val 62 |

| 23 | E-caryophyllene | −11.78 |

|

Van der Waals: Val 59, Ala 60, Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A, Val 62B |

| 24 | Limonene | −10.60 |

|

Pi-alkyl: Leu 35 Van der Waals: Asn 61, Val 62, Asn 62A, Ala 64 |

* Color reference: green dotted line indicates H-bond; faint green dotted line; indicates van der Waals interaction; lemon green dotted line indicates Pi-lone interaction; orange dotted line indicates attractive charge; dark purple dotted line indicates Pi-sigma bond; medium purple dotted line indicates Pi-amide bond; light purple dotted line indicates Pi-alkyl bond; pink dotted line indicates Pi-Pi bond.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional (3D) interaction diagram of cyclamin (saponin) against human leukocyte elastase (6F5M).

Granzyme B is a serine protease found in the granules of natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells. It is involved in inducing inflammation by cytokine release stimulation and also involved in remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Elevated levels of granzyme B are also implicated in various autoimmune diseases, several skin diseases, and type 1 diabetes [225].

On the other hand, human leukocyte elastase (HLE) is a serine proteinase involved in inflammation and tissue degradation. HLE inhibitors are believed to treat a number of diseases, such as emphysema and cystic fibrosis [220].

Natural products can have enzyme inhibitory potential for the management of different disorders [226]. According to the in silico study results, cyclamin, a saponin, is suggested to be a successful constituent for treating most underlying skin diseases owing to its chemical structure that possesses aliphatic rings, richness in oxygen atoms, and the ability to bind effectively with key amino acids of the binding sites of both granzyme B and HLE.

7. Conclusions

Herbs have great potential to treat various kinds of skin problems. Compared to various allopathic drugs, they have a comparatively low cost and can be of great benefit to many patients, especially poor people. Herbs are rich sources of active ingredients and can be a safer and cost-effective method for the management of skin ailments, ranging from rashes to skin cancer. FDA-approved formulas containing natural sources such as honey and biological cellulose are available and aid greatly in the treatment of skin diseases. Different mechanisms are displayed by such phytochemicals, such as inhibition of multiple inflammatory mediators, ranging from NF-κ, TNF-α, IL-1, TXB2, to COX-2. Their mechanism of action was elucidated via molecular modeling studies that were performed on the active sites of two essential proteins: granzyme B, which is a serine protease found in the granules of natural killer cells (NK cells) and cytotoxic T cells; and human leukocyte elastase (HLE), which is a serine proteinase involved in inflammation and tissue degradation. Molecular docking studies have confirmed that phytoconstituents of natural origin have potential beneficial effects on various skin disorders, especially those containing saponin. Owing to the aliphatic chains and structure rich in oxygen atoms, cyclamin saponin was able to display a comparable and stable complex with both enzymes. C-docker interaction energy expressed by saponin was −28.10 Kcal/mol for granzyme B and −48.50 Kcal/mol for HLE. Saponin bounded to granzyme B similarly to complexed reference via two H-bonds with Ser 100 and three H-bonds with Asn 101, Asp 176, and Thr178. It displayed van der Waals force attraction with Asn 93, Asn 95, Asn 98, and Ile 179, while it bounded to the strategic binding site of HLE via two H-bonds with Ala 60 and two H-bonds with Asn 61 and Arg 63, Pi—Pi- bonds with Leu 35, and van der Waals interaction with Arg 36, Gly 39, His 40, Val 59, Val 62, Asn 62 Chain A, Val 62 Chain B, Ile 88, and Glu 90.

List of Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| UV | Ultraviolet radiation |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa enhancer binding protein |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| C3b | Complement component 3 |

| NO | Nitric oxides |

| IL- | Interleukin 1 beta |

| TXB2 | Thromboxane B2 |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| BC | Bacterial cellulose |

| PC | Plant cellulose |

| NK | Natural killer |

| HLE | Human leukocyte elastase |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.B.S. and A.K.; methodology, I.M.F. and N.M.M.; data analysis, N.M.M., I.M.F. and A.N.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B., P.T.S., N.M.M. and I.M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.N.B.S., A.K. and N.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in this review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parvaiz M., Bhatti K.H., Nawaz K., Hussain Z., Khan R.M., Hussain A. Ethno-botanical studies of medicinal plants of Dinga, District Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013;26:826–833. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mostafa N.M., Ashour M.L., Eldahshan O.A., Singab A.N.B. Cytotoxic Activity and Molecular Docking of A Novel Biflavonoid Isolated from Jacaranda acutifolia (Bignoniaceae) Nat. Prod. Res. 2015;30:2093–2100. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1114938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashmawy A.M., Mostafa N.M., Eldahshan O.A. GC/MS Analysis and Molecular Profiling of Lemon Volatile Oil against Breast Cancer. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 2019;22:903–916. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2019.1667877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabassum N., Hamdani M. Plants used to treat skin diseases. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014;8:52. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.125531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madison K.C. Barrier function of the skin: “la raison d’etre” of the epidermis. JID. 2003;121:231–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day R.O., Snowden L. Where to find information about drugs. Aust. Prescr. 2016;3:88. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2016.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma S. Medicinal plants used in cure of skin diseases. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2016;7:65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik K., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Ullah R., Mahmood H.M., Parveen B., Rashid N., Sultana S., Shah S.N. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases in northern Pakistan. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019;19:1–38. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2605-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez-Aspajo G., Belkhelfa H., Haddioui-Hbabi L., Bourdy G., Deharo E. Sacha Inchi Oil (Plukenetiavolubilis L), effect on adherence of Staphylococus aureus to human skin explant and keratinocytes in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;171:330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay R., Bendeck S.E., Chen S., Estrada R., Haddix A., McLeod T., Mahé A. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2006. Skin Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandler D.J., Fuller L.C. A review of scabies: An infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79–90. doi: 10.1159/000495290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zari S.T., Zari T.A. A review of four common medicinal plants used to treat eczema. J. Med. Plant. Res. 2015;9:702–711. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasri H., Bahmani M., Shahinfard N., Nafchi A.M., Saberianpour S., Kopaei M.R. Medicinal plants for the treatment of acne vulgaris: A review of recent evidences. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015;8:e25580. doi: 10.5812/jjm.25580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettoli V., Zauli S., Virgili A. Is hormonal treatment still an option in acne today. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:37–46. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman A., Herman A.P. Topically used herbal products for the treatment of psoriasis–mechanism of action, drug delivery, clinical studies. Planta Medica. 2016;82:1447–1455. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-115177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan P. Skin cancer and role of herbal medicines. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018;4:404–412. doi: 10.31024/ajpp.2018.4.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahramsoltani R., Farzaei M.H., Rahimi R. Medicinal plants and their natural components as future drugs for the treatment of burn wounds: An integrative review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2014;306:601–617. doi: 10.1007/s00403-014-1474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt M.J., Barnetson R.S. A comparative study of gluconolactone versus benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of acne. Aust. J. Dermatol. 1992;33:131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1992.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sajan L. Phytochemicals, Traditional Uses. “Processing of Aconitum Species in Nepal. Nepal J. Sci. Tech. 2011;12:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sindhia V.R., Bairwa R. Plant review: Butea monosperma. Int. J. Pharm. Clin. 2010;2:90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orisakwe O.E., Afonne O.J., Chude M.A., Obi E., Dioka C.E. Sub-chronic toxicity studies of the aqueous extract of Boerhaviadiffusa leaves. J. HEALTH Sci. 2003;49:444–447. doi: 10.1248/jhs.49.444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalla J.K., Nandedkar S.Y., Paranjape M.H., Talreja N.B. Clinical trials of ayurvedic formulations in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown A.C., Hairfield M., Richards D.G., McMillin D.L., Mein E.A., Nelson C.D. Medical nutrition therapy as a potential complementary treatment for psoriasis-five case reports. Alt. Med. Rev. 2004;9:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokilavani P., Suriyakalaa U., Elumalai P., Abirami B., Ramachandran R., Sankarganesh A., Achiraman S. Antioxidant mediated ameliorative steroidogenesis by Commelinabenghalensis L. and Cissus quadrangularis L. against quinalphos induced male reproductive toxicity. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2014;109:18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang K.S., Shin E.H., Park C., Ahn Y.J. Contact and fumigant toxicity of Cyperus rotundus steam distillate constituents and related compounds to insecticide-susceptible and-resistant Blattella germanica. J. Med. Entomol. 2012;49:631–639. doi: 10.1603/ME11060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singhal M., Kansara N. Cassia tora Linn cream inhibits ultraviolet-B-induced psoriasis in rats. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2012;2012:346510. doi: 10.5402/2012/346510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein J.E., Parish L.C., Rapaport M., Rosenbaum M.M., Roenigk H.H., Jr. Effects of topically applied capsaicin on moderate and severe psoriasis vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986;15:504–507. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav H., Yadav M., Jain S., Bhardwaj A., Singh V., Parkash O., Marotta F. Antimicrobial property of a herbal preparation containing Dalbergia sissoo and Datura stramonium with cow urine against pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharm. 2008;21:1013–1020. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardel D.K., Laxmidhar S. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological of Eucalyptus globulus: A multipurpose tree. Int J. Res. Ayurveda Pharm. 2011;2:1527–1530. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chanda S., Baravalia Y. Screening of some plant extracts against some skin diseases caused by oxidative stress and microorganisms. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:3210–3217. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi A.R., Joshi K. Ethnomedicinal plants used against skin diseases in some villages of Kali Gandaki, Bagmati and TadiLikhu watersheds of Nepal. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2007;2007:27. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng C., Hu C., Ma X., Peng C., Zhang H., Qin L. Cytotoxic phenylpropanoid glycosides from Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn. Food Chem. 2012;132:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng X., Wang W., Piao H., Xu W., Shi H., Zhao C. The genus Gnaphalium L.(Compositae): Phytochemical and pharmacological characteristics. Molecules. 2013;18:8298–8318. doi: 10.3390/molecules18078298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Craig A.M., Karchesy J.J., Blythe L.L., del Pilar González-Hernández M., Swan L.R. Toxicity studies on western juniper oil (Juniperus occidentalis) and Port-Orford-cedar oil (Chamaecyparislawsoniana) extracts utilizing local lymph node and acute dermal irritation assays. Tox. Lett. 2004;154:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravichandran G., Bharadwaj V.S., Kolhapure S.A. Evaluation of efficacy & safety of Acne-N-Pimple cream in acne vulgaris. Antiseptic. 2004;101:249. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balakrishnan S., Subramanian M. A Review on Marsilea Quadrifolia L.—A Medicinally Important Plant. J.Compr. Phar. 2016;3:38–44. doi: 10.37483/JCP.2016.3201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernstein S., Donsky H., Gulliver W., Hamilton D., Nobel S., Norman R. Treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis with Relieva, a Mahonia aquifolium extract—a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Ther. 2006;13:121–126. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valiejo-Roman C.M., Terentieva E.I., Pimenov M.G., Kljuykov E.V., Samigullin T.H., Tilney P.M. Broad Polyphyly in Pleurospermum s. l. (Umbelliferae-Apioideae) as Inferred from rDNA ITS & Chloroplast Sequences. Am. Soc. Plant. Taxon. 2012;37:573–581. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parihar P., Parihar L., Bohra A. Antibacterial activity of extracts of Pinus roxburghiiSarg. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2006;35:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maimoona A., Naeem I., Saddiqe Z., Jameel K. A review on biological, nutraceutical & clinical aspects of French maritime pine bark extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:261–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin Z.X., Jiao B.W., Che C.T., Zuo Z., Mok C.F., Zhao M., Ho W.K., Tse W.P., Lam K.Y., Fan R.Q., et al. Ethyl acetate fraction of the root of Rubia cordifolia L. inhibits keratinocyte proliferation in vitro & promotes keratinocyte differentiation in vivo: Potential application for psoriasis treatment. Phytother. Res. 2010;24:1056–1064. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lomash V., Parihar S.K., Jain N.K., Katiyar A.K. Efect of Solanum nigrum & Ricinus communis extracts on histamine & carrageenan-induced infammation in the chicken skin. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;9:56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y., Liu F., Lou H.X. Studies on the chemical constituents of Solanum nigrum. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2010;33:555–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashour M.L., Ayoub N.A., Singab A.N.B., Al Azizi M.M. Simmondsia chinensis (Jojoba): A comprehensive pharmacognostic study. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2013;2:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nisar M., Khan I., Ahmad B., Ali I., Ahmad W., Choudhary M.I. Antifungal & antibacterial activities of Taxus wallichiana Zucc. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2008;23:256–260. doi: 10.1080/14756360701505336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varma S.B., Giri S.P. Study of wound healing activity of Tectona grandis Linn. leaf extract on rats. Anc. Sci. Life. 2013;32:241–244. doi: 10.4103/0257-7941.131984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goswami D.V., Nirmal S.A. An Overview of Tectona grandis: Chemistry & Pharmacological Profile. Phcog. Rev. 2009;3:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shrivastav S., Sindhu R., Kumar S., Kumar P. Anti-psoriatic & phytochemical evaluation of Thespesia populnea bark extracts. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2009;1:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raj B.A., Muruganantham N., Praveen T.K., Raghu P.S. Screening of Wrightia tinctoria leaves for anti psoriatic activity. Hygeia J. Drug Med. 2012;4:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rout S.D., Panda T., Mishra N. Ethno-medicinal plants used to cure different diseases by tribals of Mayurbhanj district of North Orissa. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2009;3:27–32. doi: 10.1080/09735070.2009.11886333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michelle Garay M., Judith Nebus M., MenasKizoulis B. Antiinflammatory activities of colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) contribute to the effectiveness of oats in treatment of itch associated with dry, irritated skin. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ashkani-Esfahani S., Imanieh M.H., Khoshneviszadeh M., Meshksar A., Noorafshan A., Geramizadeh B., Ebrahimi S., Handjani F., Tanideh N. The healing effect of arnebiaeuchroma in second degree burn wounds in rat as an animal model. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2012;14:70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pirbalouti A.G., Azizi S., Koohpayeh A. Healing potential of Iranian traditional medicinal plants on burn wounds in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012;22:397–403. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hafezi F., Rad H.E., Naghibzadeh B., Nouhi A., Naghibzadeh G. Actinidia deliciosa (kiwifruit), a new drug for enzymatic debridement of acute burn wounds. Burns. 2010;36:352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dey A., De J.N. Aristolochia indica L.: A review. Asian J. Plant. Sci. 2011;10:108–116. doi: 10.3923/ajps.2011.108.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chandra Joshi B., Sundriyal A. Healing acne with medicinal plants: An overview. Inventi J. (P) Ltd. 2017;2:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen D.L., Raub W., Bradley C., Johnson M., Macias J.L., Love V., Markoe A. The effect of aloe vera gel/mild soap versus mild soap alone in preventing skin reactions in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2001;28:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aertgeerts P., Albring M., Klaschka F., Nasemann T., Patzelt-Wenczler R., Rauhut K., Weigl B. Comparative testing of Kamillosan cream & steroidal (0.25% hydrocortisone, 0.75% fluocortin butyl ester) & non-steroidal (5% bufexamac) dermatologic agents in maintenance therapy of eczematous diseases. Z. Fur Hautkrankh. 1985;60:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.PatzeltWenczler R., Ponce Pöschl E. Proof of efficacy of Kamillosan(R)cream in atopic eczema. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2000;5:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cibin T.R., Devi D.G., Abraham A. Chemoprevention of two stage skin cancer in vivo by Saracaasoca. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:279–286. doi: 10.1177/1534735411413264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dermarderosian A. The Review of Natural Products. Kluver; Berlin, Germany: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sengul M., Ercisli S. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Activity & Total Phenolic Content within the Aerial Parts of Artemisia absinthum, Artemisia santonicum & Saponaria officinalis. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2011;10:49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tajik H., Jalali F.S., Javadi S., Shahbazi Y., Amini M. Clinical and microbiological evaluations of efficacy of combination of natural honey and yarrow on repair process of experimental burn wound. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2009;8:907–911. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barua C.C., Talukdar A., Begum S.A., Buragohain B., Roy J.D., Pathak D.C., Sarma D.K., Gupta A.K., Bora R.S. Effect of Alternanthera brasiliana (L) Kuntze on healing of dermal burn wound. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2012:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Şener G., Şatýroğlu H., Şehirli A.Ö., Kaçmaz A. Protective effect of aqueous garlic extract against oxidative organ damage in a rat model of thermal injury. Life Sci. 2003;73:81–91. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lv R.L., Wu B.Y., Chen X.D., Jiang Q. The effects of aloe extract on nitric oxide and endothelin levels in deep-partial thickness burn wound tissue in rat. Zhonghua shao shang za zhi= Zhonghuashaoshangzazhi. Chin. J. Burns. 2006;22:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jain N., Jain R., Jain V., Jain S. A review on: Abelmoschus esculentus. Pharmacia. 2012;1:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mubashir S., Shah W.A. Phytochemical and pharmacological review profile of Adiantum venustum. Int. J. Pharmtech Res. 2011;3:827–830. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brahmachari G., Gorai D., Roy R. Argemone mexicana: Chemical and pharmacological aspects. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2013;23:559–567. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2013005000021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogurtan Z., Hatipoglu F., Ceylan C. The effect of Alkanna tinctoria Tausch on burn wound healing in rabbits. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. BERL. 2002;109:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Isbir T., Yaylim I., Aydin M., Oztürk O., Koyuncu H., Zeybek U., Ağaçhan B., Yilmaz H. The effects of Brassica oleraceae var capitata on epidermal glutathione and lipid peroxides in DMBA-initiated-TPA-promoted mice. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arham S., Muhammad S., Yasir A., Liaqat A., Rao S.A., Ghulam M., Sobia A.W. Berberis lyciumRoyle: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012;6:2346–2353. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Islam M., Azhar I., Usmanghani K., Gill M.A., Ahmad A. Bioactivity evaluation of Bergenia ciliata. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002;15:15–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dharmender R., Madhavi T., Reena A., Sheetal A. Simultaneous Quantification of Bergenin,(+)-Catechin, Gallicin and Gallic acid; and quantification of β-Sitosterol using HPTLC from Bergenia ciliata (Haw.) Sternb. Forma ligulata Yeo (Pasanbheda) Pharm. Anal. Acta 1. 2010;104:2153–2435. doi: 10.4172/2153-2435.1000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bashir S., Gilani A.H. Antiurolithic effect of Bergenia ligulata rhizome: An explanation of the underlying mechanisms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ananth K.V., Asad M., Kumar N.P., Asdaq S.M., Rao G.S. Evaluation of wound healing potential of Bauhinia purpurea leaf extracts in rats. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;72:122. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.62250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rose B.N., Prasad N.K. Preliminary phytochemical and pharmacognostical evaluation of Carissa spinarum leaves. Asian J. Pharm. Tech. 2013;3:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nissen L., Zatta A., Stefanini I., Grandi S., Sgorbati B., Biavati B., Monti A. Characterization and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of industrial hemp varieties (Cannabis sativa L.) Fitoterapia. 2010;81:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pokharkar Raghunath D., Funde Prasad E., Pingale Shirish S. Aqueous extract of Capparis decidua in acute toxicity effects of the rat by use of toothache reliever activity. Pharmacologyonline. 2007;3:511–517. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suresh K. Antimicrobial and Phytochemical Investigation of the Leaves of Carica papaya L., Cynodondactylon (L.) Pers., Euphorbia hirta L., Melia azedarach L. and Psidium guajava L. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008;2008:157. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dande P.A., Khan A.N. Evaluation of wound healing potential of Cynodondactylon. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2012;5:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Srivastava P., Durgaprasad S. Burn wound healing property of Cocos nucifera: An appraisal. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2008;40:144. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.43159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saleem U., Hussain K., Ahmad M., Irfan Bukhari N., Malik A., Ahmad B. Physicochemical and phytochemical analysis of Euphorbia helioscopia (L.) Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;27:577–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lu Z.Q., Guan S.H., Li X.N., Chen G.T., Zhang J.Q., Huang H.L., Liu X., Guo D.A. Cytotoxic diterpenoids from Euphorbia helioscopia. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:873–876. doi: 10.1021/np0706163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kareparamban J.A., Nikam P.H., Jadhav A.P., Kadam V.J. Ferulafoetida “Hing”: A review. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:775. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel R., Gautam P. Medicinal potency of Ficus benghalensis: A review. Int. J. Med. Chem. Anal. 2014;4:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Geshnizjany N., Ramezanian A., Khosh-Khui M. Postharvest life of cut gerbera (Gerbera jamesonii) as affected by nano-silver particles and calcium chloride. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2014;1:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Al-Snafi A.E. Chemical constituents and medical importance of Galium aparine—A review. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018;5:1739–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arukwe U., Amadi B.A., Duru M.K., Agomuo E.N., Adindu E.A., Odika P.C., Lele K.C., Egejuru L., Anudike J. Chemical composition of Persea americana leaf, fruit and seed. Ijrras. 2012;11:346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Najafizadeh P., Hashemian F., Mansouri P., Farshi S., Surmaghi M.S., Chalangari R. The evaluation of the clinical effect of topical St Johns wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) in plaque type psoriasis vulgaris: A pilot study. Aust. J. Dermatol. 2012;53:131–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2012.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeb A., Sadiq A., Ullah F., Ahmad S., Ayaz M. Phytochemical and toxicological investigations of crude methanolic extracts, subsequent fractions and crude saponins of Isodonrugosus. Bio. Res. 2014;47:57. doi: 10.1186/0717-6287-47-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parekh J., Chanda S. In-vitro antimicrobial activities of extracts of Launaea procumbens roxb.(Labiateae), Vitis vinifera L. (Vitaceae) & Cyperus rotundus l. (Cyperaceae) Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2006;9:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jagessar R., Mohamed A., Gomes G. An evaluation of the antibacterial & antifungal activity of leaf extracts of Momordica charantia against Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus & Escherichia coli. Nat. Sci. 2008;6:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumar A., Gupta R., Mishra R.K., Shukla A.C., Dikshit A. Pharmaco-phylogenetic investigation of Micromeriabiflora Benth & Citrus reticulata Blanco. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2012;35:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Merfort I., Wray V., Barakat H., Hussein S., Nawwar M., Willuhn G. Flavonoltriglycosides from seeds of Nigella sativa. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:359–363. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00296-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ramadan M.F. Nutritional value, functional properties & nutraceutical applications of black cumin (Nigella sativa L.): An overview. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007;42:1208–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ravn H., Brimer L. Structure & antibacterial activity of plantamajoside, a caffeic acid sugar ester from Plantago major subs major. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3433–3437. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garg R., Patel R.K., Jhanwar S., Priya P., Bhattacharjee A., Yadav G., Bhatia S., Chattopadhyay D., Tyagi A.K., Jain M. Gene discovery & tissue-specific transcriptome analysis in chickpea with massively parallel pyrosequencing & web resource development. Plant. Physiol. 2011;156:1661–1678. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.178616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu J., Xiong Z., Li T., Huang H. Bioaccumulation & ecophysiological responses to copper stress in two populations of Rumex dentatus L. from cu contaminated & non-contaminated sites. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004;52:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ahmad V., Ali Z., Zahid M., Alam N., Saba N., Khan T., Qaisar M., Nisar M. Phytochemical study of Salvia moorcroftiana. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:84–85. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(99)00109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahmadiani A., Javan M., Semnanian S., Barat E., Kamalinejad M. Antiinflammatory & antipyretic effects of Trigonella foenum-graecum leaves extract in the rat. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75:283–286. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yadav U.C., Baquer N.Z. Pharmacological effects of Trigonella foenumgraecum L. in health & disease. Pharm Biol. 2014;52:243–254. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.826247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lodhi S., Pawar R.S., Jain A.P., Jain A., Singhai A.K. Effect of Tephrosia purpurea (L.) pers. On partial thickness & full thickness burn wounds in rats. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2010;1 doi: 10.2202/1553-3840.1344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Singh R., Dar S., Sharma P. Antibacterial activity & toxicological evaluation of semi purified hexane extract of Urtica dioica leaves. Res. J. Med. Plants. 2012;6:123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hadizadeh I., Peivastegan B., Kolahi M. Antifungal activity of nettle (Urtica dioica L.), colocynth (Citrullus colocynthis L. Schrad), oleander (Nerium oleander L.) & konar (Ziziphus spina-christi L.) extracts on plants pathogenic fungi. Pakistan. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;12:58. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.58.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Süntar I., Tatlı I.I., Akkol E.K., Keleş H., Kahraman Ç., Akdemir Z. An ethnopharmacological study on Verbascum species: From conventional wound healing use to scientific verification. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kimura Y., Sumiyoshi M., Sakanaka M. Effects of Astilbe thunbergii rhizomes on wound healing: Part 1. Isolation of promotional effectors from Astilbe thunbergii rhizomes on burn wound healing. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ren Z.Y., Wu Q.X., Shi Y.P. Flavonoids and triterpenoids from Anaphalismargaritacea. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2009;45:728–730. doi: 10.1007/s10600-009-9411-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jan H., Khan M.A., Usman H., Shah M., Ansir R., Faisal S., Ullah N., Rahman L. The Aquilegia pubiflora (Himalayan columbine) mediated synthesis of nanoceria for diverse biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 2020;10:19219–19231. doi: 10.1039/D0RA01971B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kumar V., Tyagi D. Antifungal activity evaluation of different extracts of Bergenia stracheyi. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2013;2:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fonseca Y.M., Catini C.D., Vicentini F.T., Nomizo A., Gerlach R.F., Fonseca M.J. Protective effect of Calendula officinalis extract against UVB-induced oxidative stress in skin: Evaluation of reduced glutathione levels and matrix metalloproteinase secretion. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Akinci I.E., Akinci S. Effect of chromium toxicity on germination and early seedling growth in melon (Cucumis melo L.) Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:4589–4594. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mukhopadhyay S., Banerjee S.K., Atal C.K., Lin L.J., Cordell G.A. Alkaloids of Corydalis govaniana. J. Nat. Prod. 1987;50:270–272. doi: 10.1021/np50050a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gomes F.S., Spínola C.D., Ribeiro H.A., Lopes M.T., Cassali G.D., Salas C.E. Wound-healing activity of a proteolytic fraction from Caricacandamarcensis on experimentally induced burn. Burns. 2010;36:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zagórska-Dziok M., Ziemlewska A., Bujak T., Nizioł-Łukaszewska Z., Hordyjewicz-Baran Z. Cosmetic and dermatological properties of selected ayurvedic plant extracts. Molecules. 2021;26:614. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bijauliya R.K., Kannojia P., Mishra P., Pathak G.K. Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Quercetin like Structure from Dalbergia sissoo (Fabaceae). J. drug deliv. Ther. 2020;10:6–11. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v10i3-s.4131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pirzada A.J., Shaikh W., Usmanghani K., Mohiuddin E. Antifungal activity of Dodonaeaviscosa Jacq extract on pathogenic fungi isolated from super ficial skin infection. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;23:337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Getie M., Gebre-Mariam T., Rietz R., Höhne C., Huschka C., Schmidtke M., Abate A., Neubert R.H. Evaluation of the anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory activities of the medicinal plants Dodonaeaviscosa, Rumex nervosus and Rumex abyssinicus. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:139–143. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ishtiaq M., Mumtaz A.S., Hussain T., Ghani A. Medicinal plant diversity in the flora of Leepa Valley, Muzaffarabad (AJK), Pakistan. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012;11:3087–3098. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Blumenthal M. Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. American Botanical Council; Austin, TX, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]