Abstract

We evaluated the effect of antiflagellar human monoclonal antibody on gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. Mice were given a suspension of P. aeruginosa SP10052 in their drinking water and were simultaneously treated with ampicillin (200 mg/kg of body weight) to disrupt the normal bacterial flora. Cyclophosphamide was then administered to induce leukopenia and translocation of the P. aeruginosa that had colonized the gastrointestinal tract, thereby producing gut-derived generalized sepsis. In this model, intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of antiflagellar human monoclonal antibody (SC-1225) per mouse for 5 consecutive days significantly (P < 0.01) increased the survival rate compared with that for mice treated with bovine serum albumin (BSA). Treatment with SC-1225 significantly reduced the average number of viable bacteria in portal blood, liver, and heart blood compared with the average number after treatment with BSA. Furthermore, the presence in serum of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 6 were evaluated as markers of severity of infection, and the results showed that the levels of these cytokines in mice treated with SC-1225 were significantly decreased in comparison with those in BSA-treated control mice. Although there was no significant difference in the number of bacteria that colonized the intestine, SC-1225 treatment significantly increased bacterial opsonophagocytosis by cultured peritoneal macrophages from mice with or without cyclophosphamide pretreatment. Our results indicate that antiflagellar human monoclonal antibody SC-1225 protects mice against gut-derived sepsis caused by P. aeruginosa and suggest that such an effect is due to its opsonophagocytic activity and the reduced motility of the translocated bacteria once the bacteria move from the intestine into the bloodstream.

Infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common pathogen that causes septicemia in immunocompromised hosts, has a higher fatality rate than any other gram-negative bacterial infection. Although antibiotic therapy is thought to be the most effective therapy against infections caused by this microorganism, such therapy is frequently ineffective due to bacterial resistance. Therefore, effective immunotherapy may be a useful alternative therapy administered either alone or in combination with antibiotic chemotherapy.

Some reports have shown that neutrophils (36), complement (2), and immunoglobulins (32) play important roles in host defense against P. aeruginosa infection. However, P. aeruginosa is frequently identified as a causative agent of sepsis in immunocompromised patients with neutropenia induced by antineoplastic chemotherapy (13). Because normal neutrophil function is not expected in patients with neutropenia, humoral immune responses may play a more important role in the recovery of such patients from P. aeruginosa infection. Vaccination with microbial antigens may be the most effective method for the induction of protective humoral immune responses (9). However, vaccination of immunocompromised hosts is frequently unsuccessful due to immunodeficiency (18). Therefore, passive immunization may be a more practical method for immunotherapy to protect individuals against P. aeruginosa infection.

Because experimental data suggest that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important virulence factor in P. aeruginosa infection, the protective action of anti-LPS antibody or polysaccharide vaccines has attracted the attention of several groups of investigators (8–10, 34, 35). Unfortunately, however, due to the presence of various LPS serotypes of P. aeruginosa, it is difficult to produce protective antibodies against a broad spectrum of P. aeruginosa isolates (10, 30, 34, 35, 38, 40). In contrast to LPS, there are only two known serotypes (designated serotypes a and b) of P. aeruginosa flagella (5). Flagella are also important virulence factors in P. aeruginosa infection (14, 17). Thus, antibodies against flagellar antigens may be more useful than those directed against LPS in protecting hosts against a wide range of P. aeruginosa infections. These considerations led us to investigate the effects of antiflagellar antibodies on murine gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis associated with neutropenia induced by antineoplastic chemotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MAb.

Human immunoglobulin M (IgM) monoclonal antibody (MAb) SC-1225 was kindly provided by Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals Co., Osaka, Japan. This MAb, which specifically reacts with b-serotype flagella, is purified chromatographically.

Bacterial strain.

P. aeruginosa SP10052, a clinical isolate that is known to react with MAb SC-1225 (39), was also provided by Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals. The strain was kept frozen at −80°C in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 15% glycerol.

Animals.

Inbred, specific-pathogen-free male ddY mice (Japan Shizuoka Laboratory Center Co., Shizuoka, Japan) weighing 20 to 24 g were used in our experiments. The animals were housed in sterile cages and received sterile distilled water except when P. aeruginosa was being orally administered. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Toho University School of Medicine.

Survival of mice with gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis.

Gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis was produced as described previously (24, 26). Briefly, bacteria were grown on Trypticase soy agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) at 37°C for 18 h, suspended in sterile 0.45% saline, and adjusted to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml. The bacterial suspension was added to the drinking water on days 1 to 3. To promote colonization of P. aeruginosa SP10052, which is insensitive to ampicillin (ABPC), 200 mg of ABPC per kg of body weight was administered by daily intraperitoneal injections on days 1 to 3 in order to produce a disturbance of the normal intestinal flora. This was followed by intraperitoneal injection of 150 to 200 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg on days 5 and 8. Each experiment was repeated at least twice. The lethal effects of infection were checked every 24 h for 7 days (see Fig. 1). MAb SC-1225 was injected intraperitoneally (100 μg/day) for 5 days, commencing after administration of the second cyclophosphamide dose. Control mice received identical amounts of bovine serum albumin (BSA).

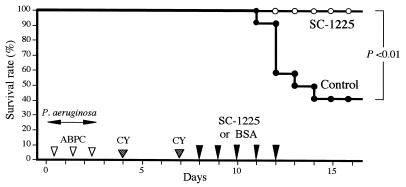

FIG. 1.

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on the survival of mice with gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis. Each mouse (n = 10) received 100 μg of an antiflagellar human MAb (MAb SC-1225) for 5 consecutive days at 24-h intervals following the second cyclophosphamide treatment by intraperitoneal injections. Control mice (n = 10) received 100 μg of BSA on the same schedule. CY, cyclophosphamide.

Tissue sampling and determination of viable bacteria.

Mice from each treatment group were killed by exposure to ether at the indicated time intervals. Under aseptic conditions, blood samples were taken from the portal vein and cardiac chamber. Under similar conditions, liver tissue specimens were obtained and were immediately homogenized in sterile saline. Portions of the blood samples and liver homogenates were plated onto Trypticase soy agar and were cultured at 37°C for 24 h to detect and identify the P. aeruginosa challenge strain. The remaining blood samples were allowed to clot at 4°C in sterile glass tubes and were then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min. Serum samples were preserved at −80°C until measurement of cytokine levels.

Determination of intestinal colonization.

Fecal samples were collected from mice 4 days after administration of the second dose of cyclophosphamide. The samples were weighed and were homogenized with 2 ml of sterile saline, and the homogenates were serially diluted. Fifty-microliter portions of the various dilutions were plated onto NAC agar (Eiken Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and were cultured at 37°C for 24 h. The number of CFU per gram was calculated by counting the number of colonies that grow on the agar.

Opsonophagocytosis of bacteria by cultured murine macrophages.

The effect of MAb SC-1225 on phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa SP10052 by murine peritoneal macrophages was assessed as follows. Peritoneal macrophages freshly drawn from untreated healthy mice were washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), after which 500 μl of the resulting cell suspension (106 cells/ml) was placed into each well of a 24-well tissue culture plate (Falcon 3047; Becton Dickinson & Co., Franklin Lakes, N.J.) and the plate was incubated for 1 h. Bacteria at the logarithmic growth phase was suspended with RPMI 1640 medium at a concentration of 105 CFU/ml and were incubated for 30 min without or with 0.1 or 1 μg of SC-1225 per ml. Five hundred-microliter volumes of each bacterial suspension were added to separate wells of a tissue culture plate, and the mixture was incubated with rocking for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The number of viable bacteria in the culture supernatants was determined by plating the supernatant on Mueller-Hinton agar and culturing at 37°C for 24 h.

Furthermore, we determined the effects of MAb SC-1225 on phagocytosis by using peritoneal macrophages from mice treated with 200 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg intraperitoneally 1 or 2 days before the assay.

Cytokine assay.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels in mouse serum were determined with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Endogen Inc., Boston, Mass.). IL-1β concentrations were assessed with a commercially available ELISA kit (Genzyme Corp., Boston, Mass.). The assays were performed exactly as described by the manufacturers, and the levels in each sample were determined in duplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in survival rates among groups were evaluated by the chi-square test. Viable bacterial counts and cytokine concentrations were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on survival of mice.

We measured the protective effect of an antiflagellar MAb (MAb SC-1225) in mice with gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis. As shown in Fig. 1, the survival rate of mice treated with SC-1225 was significantly higher than that of the control mice (P < 0.01). These results suggest that administration of SC-1225 protects mice against gut-derived sepsis.

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on viable bacterial counts.

In our mouse model, P. aeruginosa isolates that colonize the gastrointestinal tract invade the bloodstream and, after breaking through the defense system provided by the liver, spread into the systemic circulation. We therefore examined viable bacterial counts in the portal blood, liver, and heart blood in mice treated with antiflagellar MAb and in control BSA-treated mice. The results demonstrated that administration of SC-1225 significantly suppressed the number of viable bacteria in the portal blood, liver, and heart blood (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on the number of viable bacteria in various organsa

| Group | Count (CFU/ml [10]) in portal vein | Count 103 (CFU/g [103]) in liver | Count (CFU/ml [10]) in heart blood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3,484.0 ± 2356.0 | 899.6 ± 426.0 | 2,0092.0 ± 1,992.0 |

| SC-1225 treated | 5.2 ± 1.2b | 1.1 ± 0.7c | 4.0 ± 2.4b |

Samples for bacterial count determinations were collected 3 days after administration of the second dose of cyclophosphamide (n = 5).

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

Influence of antiflagellar MAb on serum cytokine levels during gut-derived sepsis.

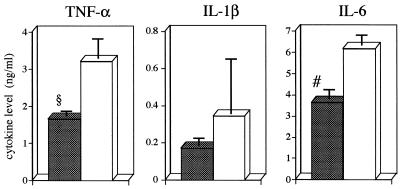

Since the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are thought to be good markers of the severity of bacterial infections (11, 24, 31), we determined the levels of these cytokines in mice with gut-derived sepsis after antiflagellar MAb treatment. As depicted in Fig. 2, the results demonstrated significant decreases in TNF-α and IL-6 levels in SC-1225-treated mice in comparison with those in BSA-treated control mice. Although there was no significant difference, IL-1β levels also showed a tendency to decrease in mice treated with SC-1225.

FIG. 2.

Influence of antiflagellar MAb on serum cytokine levels during gut-derived sepsis. MAb SC-1225 was administered intraperitoneally at 100 μg/mouse (closed columns) for 3 consecutive days at 24-h intervals following the second cyclophosphamide treatment. BSA was administered to control animals (open columns) at the same intervals. Serum samples were collected 3 days after administration of the second dose of cyclophosphamide. Values are means ± standard errors of the means (six mice in each group). Symbols: #, P < 0.05; §, P < 0.01.

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on colonization of P. aeruginosa in intestinal tract.

Because the reservoir of P. aeruginosa in the model used in this study is thought to be the gastrointestinal tract, we determined the effect of MAb SC-1225 on the ability of the bacteria to colonize the intestine. This was performed by measurement of viable bacterial counts in the feces 4 days after administration of the second dose of cyclophosphamide. The average numbers of viable P. aeruginosa in the feces of SC-1225-treated mice and BSA-treated mice were 7.2 × 104 ± 2.8 × 104 and 1.3 × 105 ± 2.6 × 104 CFU/g, respectively (means ± standard errors of the means). Although the bacterial count in mice treated with SC-1225 was slightly lower than that in BSA-treated mice, the difference was not significant.

Influence of antiflagellar MAb on opsonophagocytosis.

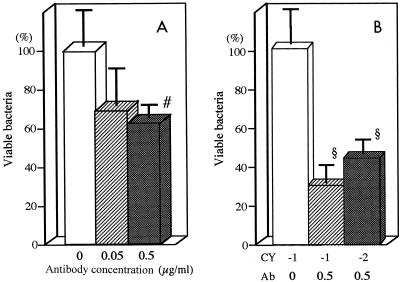

To evaluate another mechanism by which MAb SC-1225 might protect mice against gut-derived sepsis, we studied the effect of the antibody on in vitro opsonophagocytosis of P. aeruginosa SP-10052 by murine peritoneal macrophages. The results are depicted in Fig. 3A. Although incubation with 0.05 μg of SC-1225 per ml tended to reduce the number of viable bacteria in the medium, the difference was not statistically significant compared with the number for untreated controls. However, incubation with 0.5 μg of SC-1225 per ml significantly reduced the number of viable bacteria in the medium compared with that for the untreated controls.

FIG. 3.

Effect of antiflagellar MAb on opsonophagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by murine peritoneal macrophages. P. aeruginosa SP10052 was preincubated with MAb SC-1225 and was then incubated with rocking in a 24-well tissue culture plate with peritoneal macrophages. (A) Counts of viable bacteria were determine in the culture supernatants of SC-1225-treated groups (final concentrations, 0.05 and 0.5 μg/ml) and a control group not treated with SC-1225. (B) Mice were treated with 200 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg intraperitoneally 1 or 2 days before the opsonophagocytosis test. Counts of viable bacteria were determined in the culture supernatants after incubation with peritoneal macrophages from mice treated with cyclophosphamide 1 or 2 days before the assay and incubated with 0.5 μg of SC-1225 per ml. For the control group, peritoneal macrophages were drawn from mice treated with cyclophosphamide 1 day before the assay and incubated without SC-1225. Each bar shows the average number of viable bacteria as a percentage of that in the untreated control group. CY, day of cyclophosphamide treatment; Ab, antibody concentration (in micrograms per milliliter). Data represent the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 8 for each group). Symbols: §, P < 0.01; #, P < 0.05 compared with the control group.

Because all in vivo experiments were performed with the cyclophosphamide-treated mice, we further evaluated the effects of 0.5 μg of SC-1225 per ml on phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by using peritoneal macrophages from mice treated with cyclophosphamide 1 or 2 days before the assay. The results revealed that SC-1225 significantly reduced the number of viable bacteria in the medium compared with that for the control group even in a test with macrophages from cyclophosphamide-treated mice (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the protective effects of SC-1225 might be mediated at least in part by enhancement of opsonophagocytic activity.

DISCUSSION

Clinical studies with surveillance cultures of fecal samples from immunocompromised patients suggest that the gastrointestinal tract may be a primary reservoir for opportunistic bacteria (37). Previous studies have shown that bacteria within the gut can cross the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier and spread systemically, a process termed bacterial translocation (6, 12). Berg et al. (7) reported that gram-negative enteric bacilli of the gastrointestinal tract systemically translocate in mice treated with a combination of antibiotics and immunosuppressive drugs, such as penicillin G sodium and cyclophosphamide. We induced acute enteritis by administering APBC and cyclophosphamide to specific-pathogen-free mice fed P. aeruginosa. In this model, P. aeruginosa colonizes the intestinal tract and can invade body tissues after induction of immunosuppression or disruption of the intestinal mucosal barrier by administration of cyclophosphamide. Once the bacteria escape Kupffer cells in the liver, they disseminate systemically, causing bacteremia and septicemia, which is usually followed by death of the animal. This model therefore resembles the septicemia in humans caused by pathogens derived from the intestinal tract, particularly in immunocompromised hosts (20).

Concerning the role of administration of cyclophosphamide in this model, we think that the effect of this compound on the number of neutrophils is important for the induction of sepsis. In our preliminary experiment, the leukocyte count decreased less than 1,000/mm3 for 3 to 4 days after cyclophosphamide treatment. Furthermore, we also determined that the activity of Kupffer cells is also depressed by the administration of cyclophosphamide (data not shown).

Our murine gut-derived P. aeruginosa sepsis model is suitable for studying the effects of antiflagella antibodies against sepsis. We have previously used this model to evaluate the protective efficacy of immunization with heat-killed P. aeruginosa and found that such immunization provided complete protection against death (25). We also evaluated the protective efficacies of vaccines prepared from P. aeruginosa alkaline protease, elastase, and exotoxin A toxoids. The results showed that a combination of alkaline protease and exotoxin A toxoids is a logical candidate as a vaccine against P. aeruginosa sepsis (23). These studies established the efficacy of immunotherapy with antibodies in P. aeruginosa sepsis.

The major finding of the present study was the protective effect of MAb SC-1225, an antiflagellar human MAb, against P. aeruginosa sepsis. Our results also indicated that flagella are important components in the pathogenesis of gut-derived sepsis. The model used in the present study incorporates four features: oral inoculation of bacteria, subsequent bacterial colonization, overgrowth in the intestinal tract, and invasion into the bloodstream. Therefore, to determine the mechanism of action of SC-1225, we first investigated the number of viable bacteria in the portal blood, liver, and heart blood and found that they were significantly decreased by SC-1225. However, our results suggested that SC-1225 failed to influence intestinal colonization of the bacteria; the number of P. aeruginosa isolates in the intestines of mice treated with SC-1225 was not lower than the number in control mice. These results suggest that administration of antiflagellar MAb reduced the motility of translocated bacteria once the bacteria moved from the gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream and then contributed to the protection.

A number of studies have demonstrated the protective effects of antiflagellar antiserum or MAbs against lethal P. aeruginosa infections in a burn wound model (15, 19, 21, 28, 33, 39) and in a pneumonia model (22, 29). Landsperger et al. (22) demonstrated that decreased bacterial motility by antiflagellar antibody is associated with a decreased pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa in rat model of pneumonia (22). As a mechanism of protective effects of antiflagellar antibodies, Anderson and Montie (3, 4) reported that antiflagellar antibodies stimulate opsonophagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The present results also showed that incubation with a high dose of MAb SC-1225 accelerated opsonophagocytosis of P. aeruginosa. These findings suggest that the opsonophagocytic activity of antiflagella antibodies may be another mechanism by which they exert their protective effects against sepsis, besides their inhibitory activity on bacterial motility. We also speculated that the other mechanism of the protective effect of SC-1225 against gut-derived sepsis is the lessening of bacterial translocation, and we are now investigating this possibility.

Isolation and characterization of MAb SC-1225 (originally designated IN-2A8) was reported by Ochi et al. (28), who demonstrated that it strongly inhibited bacterial motility in vitro. Uezumi et al. (39), however, reported that SC-1225 alone did not protect mice against intraperitoneal infection, while combination therapy with SC-1225 and imipenem-cilastatin significantly improved the survival rate. In the present study, we demonstrated a protective effect for SC-1225 against murine sepsis without the simultaneous use of antibiotics. We speculate that the reason for different results may be due to differences in the experimental design. For example, Uezumi et al. (39) inoculated the bacteria intraperitoneally into healthy mice, while we selected the oral route and used cyclophosphamide-treated leukopenic mice. Furthermore, the model used by Uezumi et al. (39) represents acute sepsis; the rapid growth of the infecting bacteria, observed in both the peritoneum and blood, results in the death of all mice within 10 h following infection. In our model, however, few untreated mice were still alive on the 3rd or 4th day. Most significantly, however, our approach provides a specific model of gut-derived septicemia, in which bacterial translocation across the gut wall is a key step. This step is bypassed in the experimental model of Uezumi et al. (39).

A high dose of 10 μg of antiflagellar MAb was previously found to provide protection against P. aeruginosa pneumonia in the neutropenic mouse (29). Uezumi et al. (39) initially used that dose; however, it was found to be ineffective in their model, and a higher dose, e.g., 100 or 500 μg per mouse, was needed. Similarly, our preliminary experiments showed that a dose of 10 μg of MAb SC-1225 per mouse was ineffective against gut-derived sepsis in the model used in the present study (data not shown). The protective effect of this MAb was noted only when the dose was increased to 100 μg/mouse and was administered for 5 consecutive days. These results suggest that a relatively high dose of SC-1225 may be required to protect against in vivo infection, particularly when the MAb is used alone.

We and other investigators reported that inflammatory cytokines, especially TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, play important roles in the pathological manifestations of septic shock (1, 27). These cytokines are also thought to be good markers of the severity of infection during bacterial infections (11, 24, 31). Therefore, we determined the levels of these cytokines in mice after gut-derived sepsis, and the results demonstrated significant decreases in TNF-α and IL-6 levels in antiflagellar MAb-treated mice in comparison with those in BSA-treated control mice. These results indicate that antiflagellar MAb treatment ameliorates the P. aeruginosa infection and then influences cytokine production.

We have previously reported that blood culture-derived isolates are more virulent in the murine gut-derived sepsis model than other clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa (16) and that the mean motility of P. aeruginosa blood-derived isolates is significantly higher than that of sputum-derived isolates (19). Furthermore, infection with high-motility strains of P. aeruginosa results in significantly higher mortality rates than infection with low-motility strains in our murine gut-derived sepsis model (19). In this report we demonstrated the protective effect of antiflagellar human MAb SC-1225 against gut-derived sepsis caused by P. aeruginosa, and one of the protective mechanisms is suspected to be its opsonophagocytic activity. We therefore conclude that the flagella of P. aeruginosa play an important role in the gut-derived sepsis caused by this organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Shogo Kuwahara for useful advice and to Yasuko Kaneko for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by a research grant provided by The Japan Health Sciences Foundation, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander H R, Doherty G M, Venzon D J, Merino M J, Fraker D L, Norton J A. Recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra): effective therapy against gram-negative sepsis in rats. Surgery. 1992;112:188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert S E, Pennington J E, Colten H R. Synthesis of complement by guinea pig bronchoalveolar macrophages. Effect of acute and chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:66–71. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson T R, Montie T C. Flagellar antibody stimulated opsonophagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with response to either a- or b-type flagellar antigen. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35:890–894. doi: 10.1139/m89-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson T R, Montie T C. Opsonophagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa treated with antiflagellar serum. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3204–3206. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3204-3206.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansorg R A, Knoche M E, Spies A F, Kraus C J. Differentiation of the major flagellar antigens of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the slide coagglutination technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:84–88. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.1.84-88.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg R D, Garlington A W. Translocation of Escherichia coli from the gastrointestinal tract to the mesenteric lymph nodes in gnotobiotic mice receiving Escherichia coli vaccines before colonization. Infect Immun. 1980;30:894–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.3.894-898.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg R D, Wommack E, Deitch E A. Immunosuppression and intestinal bacterial overgrowth synergistically promote bacterial translocation. Arch Surg. 1988;123:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400350073011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharjee A K, Opal S M, Palardy J E, Drabick J J, Collins H, Taylor R, Cotton A, Cross A S. Affinity-purified Escherichia coli J5 lipopolysaccharide-specific IgG protects neutropenic rats against gram-negative bacterial sepsis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:622–629. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cryz S J, Jr, Furer E, Germanier R. Protection against fatal Pseudomonas aeruginosa burn wound sepsis by immunization with lipopolysaccharide and high-molecular-weight polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1984;43:795–799. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.795-799.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cryz S J, Jr, Furer E, Germanier R. Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a murine burn wound sepsis model by passive transfer of antitoxin A, antielastase, and antilipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1072-1079.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damas P, Ledoux D, Nys M, Vrindts Y, De Groote D, Franchimont P, Lamy M. Cytokine serum level during severe sepsis in human IL-6 as a marker of severity. Ann Surg. 1992;215:356–362. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deitch E A, Winterton J, Berg R. Thermal injury promotes bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract in mice with impaired T-cell-mediated immunity. Arch Surg. 1986;121:97–101. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400010111015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dick J, Shull V, Karp J. Valentine J. Bacterial and host factors affecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonisation versus bacteremia in granulocytopenic patients. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;25(Suppl. 1):S47–S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake D, Montie T C. Flagella, motility and invasive virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:43–52. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake D, Montie T C. Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by passive transfer of anti-flagellar serum. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:755–763. doi: 10.1139/m87-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuya N, Hirakata Y, Tomono K, Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Kaku M, Yamaguchi K. Mortality rates amongst mice with endogenous septicaemia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from various clinical sources. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:141–146. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-2-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goto S. Recent progress in the identification of pathogenic factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Chemother. 1996;2:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb D J, Cryz S J, Jr, Furer E, Que J U, Prentice H G, Duncombe A S, Brenner M K. Immunity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa adoptively transferred to bone marrow transplant recipients. Blood. 1990;76:2470–2475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatano K, Matsumoto T, Furuya N, Hirakata Y, Tateda K. Role of motility in the endogenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis after burn. J Infect Chemother. 1996;2:240–246. doi: 10.1007/BF02355121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirakata Y, Furuya N, Tateda K, Kaku M, Yamaguchi K. In vivo production of exotoxin A and its role in endogenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2468–2473. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2468-2473.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holder I A, Naglich J G. Experimental studies of the pathogenesis of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: immunization using divalent flagella preparations. J Trauma. 1986;26:118–122. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198602000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landsperger W J, Kelly-Wintenberg K D, Montie T C, Knight L S, Hansen M B. Inhibition of bacterial motility with human antiflagellar monoclonal antibodies attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced pneumonia in the immunocompetent rat. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4825–4830. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4825-4830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Furuya N, Miyazaki S, Ohno A, Ishii Y, Hirakata Y, Yamaguchi K. Efficacies of alkaline protease, elastase, and exotoxin A toxoid vaccines against gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in mice. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:303–308. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Miyazaki S, Furuya N, Ohno A, Ishii Y, Hirakata Y, Yamaguchi K. Adverse effects of tumor necrosis factor in cyclophosphamide-treated mice subjected to gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. Cytokine. 1997;9:763–769. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Miyazaki S, Furuya N, Ohno A, Ishii Y, Hirakata Y, Yamaguchi K. Effect of immunisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa on gut-derived sepsis in mice. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:295–301. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Miyazaki S, Furuya N, Ohno A, Ishii Y, Hirakata Y, Yamaguchi K. Immunomodulating effect of fosfomycin on gut-derived sepsis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:308–313. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto, T., K. Tateda, S. Miyazaki, N. Furuya, A. Ohno, Y. Ishii, Y. Hirakata, and K. Yamaguchi. Paradoxical synergistic effects of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 on murine gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. Cytokine, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Ochi H, Ohtsuka H, Yokota S, Uezumi I, Terashima M, Irie K, Noguchi H. Inhibitory activity on bacterial motility and in vivo protective activity of human monoclonal antibodies against flagella of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1991;59:550–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.550-554.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oishi K, Sonoda F, Iwagaki A, Ponglertnapagorn P, Watanabe K, Nagatake T, Siadak A, Pollack M, Matsumoto K. Therapeutic effects of a human antiflagella monoclonal antibody in a neutropenic murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:164–170. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington J E, Small G J, Lostrom M E, Pier G B. Polyclonal and monoclonal antibody therapy for experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun. 1986;54:239–244. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.239-244.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puren A J, Feldman C, Savage N, Becker P J, Smith C. Patterns of cytokine expression in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 1995;107:1342–1349. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson J D, DeCamp M M, Garrison R N, Fry D E. Pulmonary infection complicating intra-abdominal sepsis: clinical and experimental observations. Ann Surg. 1982;195:732–738. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198206000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosok M J, Stebbins M R, Connelly K, Lostrom M E, Siadak A W. Generation and characterization of murine antiflagellum monoclonal antibodies that are protective against lethal challenge with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3819–3828. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3819-3828.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawada S, Kawamura T, Masuho Y. Immunoprotective human monoclonal antibodies against five major serotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3581–3590. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-12-3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoll B J, Pollack M, Young L S, Koles N, Gascon R, Pier G B. Functionally active monoclonal antibody that recognizes an epitope on the O side chain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa immunotype-1 lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1986;53:656–662. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.656-662.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura Y, Suzuki S, Sawada T. Role of elastase as a virulence factor in experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90058-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tancrede C H, Andremont A O. Bacterial translocation and gram-negative bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:99–103. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terashima M, Uezumi I, Tomio T, Kato M, Irie K, Okuda T, Yokota S, Noguchi H. A protective human monoclonal antibody directed in the outer core region of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.1-6.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uezumi I, Terashima M, Kohzuki T, Kato M, Irie K, Ochi H, Noguchi H. Effects of a human antiflagellar monoclonal antibody in combination with antibiotics on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1290–1295. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.6.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokota S, Terashima M, Chiba J, Noguchi H. Variable cross-reactivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide-code-specific monoclonal antibodies and its possible relationship with serotype. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:289–296. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-2-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]