Abstract

A monoclonal antibody (MAb) was obtained from a mouse immunized with solubilized outer membrane proteins extracted from a bovine enterohemorrhagic strain of Escherichia coli (EHEC), O26. The MAb produced a strong immunoblot reaction at approximately 21 kDa for an O26 strain containing the intimin gene (eae) and verocytotoxin (VT), but not with an O26 eae- and VT-negative strain, or O157 eae- and VT-positive strains. The MAb was used in a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format to screen strains from animal and human sources, and all reactive strains were characterized for the presence of eae and the gene encoding VT factors by PCR. The antigen was detected in a group of strains containing a high proportion of O26, the majority of which were eae positive with or without VT; these were isolated mostly from animal enteritis cases but included a small number of human enteric isolates. Nonreactors included eae-positive (with or without VT) O157 strains and one O26 strain. In a survey of mixed cultures from both animal and human enteric disease, ELISA-positive reactions were obtained from 7.1 to 11.2% of samples from bovine, porcine, ovine, and human sources. The two human O8 and ten animal O26 ELISA-reactive pure strains obtained from these samples contained six eae- and/or VT-positive strains; the other six strains lost their ELISA positivity following storage at −70°C, after which none were found to contain either eae or VT factors. The association of the antigen detected by the MAb with significant enteropathogenic E. coli and EHEC virulence factors in isolates from both animal and human enteric infections indicates a diagnostic potential for the assay developed.

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) has been defined as a pathogenic group of strains characterized by their intimate attachment to the mammalian gut wall, leading to the production of attachment and effacement (a/e) lesions, and by verocytotoxin (VT) production (19). Another pathogenic group, the enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), is also characterized by causing a/e lesions but differs from EHEC in that it does not produce VTs. Strains from both these groups are important causes of human enteric diseases (29). EHEC strains have become prominent in recent years as causes of hemorrhagic enteritis and the hemolytic uremic syndrome. The main serogroup implicated in human disease caused by EHEC has been O157 (10), but other serogroups, in particular O26, O103, O111, and O128, have also been implicated in causing human disease (13, 22, 32).

EHEC and EPEC strains are also associated with enteric disease in cattle (5, 6, 8, 20, 21, 25, 27, 31, 33, 37). The significance of these pathogenic groups in bovine enteritis is probably underestimated, possibly because of a lack of awareness of their significance and a lack of appropriate assays for routine detection. The widespread presence of VT-producing E. coli strains in healthy cattle is also a complication (3, 8, 26, 35). Demonstration of VT in cultures from bovine enteritis is not sufficient to imply a causative association.

The object of the present study was to produce monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to EHEC surface adhesion antigens, and to investigate their diagnostic application for the detection of EHEC in animal and human enteric infections. Because of an association with both human and bovine diseases, an EHEC strain of serotype O26 was selected for investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of antigens.

An outer membrane (OM) preparation of E. coli O26 strain 4276 was prepared by the standard sarcosine extraction method (11). This strain was isolated from a calf enteritis case in Northern Ireland and was characterized as intimin (encoded by gene eae) and VT positive. Briefly, washed cells from an overnight broth culture, suspended in 0.01 M Tris HCl–0.005 M EDTA buffer, pH 7.8, were disrupted by ultrasonication. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min to remove intact cells, the supernatant was mixed with a quarter volume of 2% (wt/vol) sodium n-lauroylsarcosine (Sigma) in Tris-EDTA buffer at room temperature for 30 min and ultracentrifuged at 300,000 × g for 1 h. The resuspended pellet was reextracted with an equal volume of 2% sarcosine for 1 h at room temperature, repelleted, washed once in saline, and stored at −70°C.

Some of the washed OM was solubilized in a 6 M solution of the chaotropic agent guanidine thiocyanate (Sigma) in Tris-EDTA. Insoluble material was removed by ultracentrifugation, and the outer membrane protein (OMP) solution was dialyzed against 100 volumes of 6 M urea in Tris-EDTA buffer and stored at −70°C.

MAbs.

A BALB/c mouse was immunized intraperitoneally with the solubilized OMP preparation of E. coli O26 strain 4276. Three inoculations of 100 μl, 50 μl, and 50 μl of OMP solution, each mixed with 50 μl of adjuvant (125 μg of Quil A per ml) (Superfos; DK-Vedbaek, Denmark), were given at 4-week intervals. Three days after the final inoculation, the mouse spleen cells were fused with the NSO myeloma cells at a ratio of 8:1 according to the protocol of Galfre and Milstein (12) with modifications by Teh and Wong (34). The resulting hybridomas were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom), supplemented with 20% gamma-globulin-free horse serum (Gibco).

The cell culture fluids from actively growing hybridomas were initially screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in microtiter plate wells (Dynatech, McLean, Va.) coated with OM preparations of E. coli O26 strains 4276 (eae and VT positive) and 1045 (eae and VT negative). The hybridomas showing specific reaction to strain 4276 antigen were cloned twice by limiting dilution.

Sandwich ELISA.

Ascites was produced by the intraperitoneal inoculation of BALB/c mice with cloned hybridoma lines. The mice were primed by intraperitoneal inoculation of Freund’s incomplete adjuvant 2 days before cell inoculation (28). Ascites fluid was removed from the mice approximately 10 days later and stored at −20°C. Immunoglobulin was purified from the ascites fluid by caprylic acid precipitation (24).

The sandwich ELISA was performed on microtiter plates (Dynatech) as previously described (2–4). Briefly, 100 μl of each reagent was used per well. Optimum reagent dilutions were established by titration. The test samples were carried out in PTN (0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline [pH, 7.2] containing 0.04% [vol/vol] Tween 80 and additional NaCl [2%, vol/vol]). Between stages, the plate was washed six times with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Purified MAb in 0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.5, was used to coat the wells either at 4°C overnight or at 37°C for 1 h. The incubation stages thereafter were all 1 h at 37°C, except for the final substrate stage, which was 10 min. The intervening sequential stages consisted of the test sample, the biotinylated MAb (16), and the streptavidin-peroxidase (Sigma). The peroxidase substrate used was 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine hydrochloride (Chemicon International, Temecula, Calif.). The substrate reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl of 2.5 M H2SO4 per well. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with an ELISA plate reader (Titertek Mulitskan). The positive and negative controls consisted of E. coli strain 4276 and growth medium, respectively. Readings of greater than three times the average negative-control value were taken as positive reactions.

The sandwich ELISA sensitivity was determined by using dilutions of strain 4276 after incubation at 37°C for 18 h on bovine blood agar plates. Decimal dilutions were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline, and viable counts were determined on bovine blood agar after overnight incubation.

A range of E. coli strains were used to evaluate the sandwich ELISAs. These were selected as representative strains of several pathogenic groups (Table 1). Apart from the two rabbit O103 strains, which were obtained from A. Milon, Ecole Nationale Veterinaire, Toulouse, France, all were isolated in Northern Ireland. In addition, the ELISAs were tested by using representative strains from other Enterobacteriaceae genera and assorted gram-negative species. Each strain tested was cultured overnight at 37°C on bovine blood agar. A loopful of the colony was mixed in 1 ml of PTN for application as a test sample to the sandwich ELISA.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used for the preliminary testing of MAbs 2F3 and 6G5

| Source | Strain | Pathotypea | Serotype | eae | VT1 | VT2 | 2F3 ELISA | 6G5 ELISA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine | 4276 | EHEC | O26 | + | + | − | + | + |

| Bovine | 237 | EHEC | O26 | + | + | − | + | − |

| Bovine | 4618 | EPEC | O26 | + | − | − | + | − |

| Human | 1045 | ETEC | O26 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | E7 | NTEC | O15 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | S306 | NTEC | UT | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | S1378 | NTEC | UT | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | S784 | EHEC | O157 | + | + | − | − | − |

| Bovine | 3680 | EPEC | O157 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | S951 | EHEC | O157 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Bovine | 108 | VTEC | O117 | − | − | + | − | − |

| Bovine | 286 | ETEC | O141 | − | − | + | − | − |

| Bovine | 335 | ETEC | O139 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bovine | 413 | VTEC | O103 | − | + | − | − | − |

| Porcine | 2353 | ETEC | O149 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lapine | B10 | EPEC | O103 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Lapine | E22 | EPEC | O103 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Human | H217 | VTEC | O146 | − | − | + | − | − |

ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; NTEC, necrotoxigenic E. coli; VTEC, verocytotoxic E. coli.

Test samples.

The MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA was further applied to a number of E. coli strains. These consisted of isolates collected from field cases of animal enteritis in Northern Ireland, from bovine enteritis cases in Belgium, and from healthy calves in Belgium. A small number of bovine O157 strains previously isolated in Northern Ireland (1) were also included, as were a small number of isolates from cases of human diarrhea.

In addition, the assay was used to directly test mixed colony sweeps from fresh overnight agar cultures of fecal samples, from animal and human enteritis cases submitted to the Veterinary Sciences Division laboratories in Belfast and the Northern Ireland Public Health Laboratory, respectively. Six individual colonies from mixed agar cultures, demonstrating a positive ELISA reaction, were purified and tested individually. Purified, ELISA-positive reactants were O-serotyped and tested for the presence of eae and VT as above.

PCR.

All of the ELISA-positive, and some of the ELISA-negative, strains were tested for eae by PCR. A proportion of these were similarly tested for the gene encoding VT. The primers used in the procedure differed in the Northern Irish (23) and the Belgian (7) laboratories.

Serogrouping.

All E. coli isolates obtained in Northern Ireland were O-typed by slide agglutination (30), by using a collection of 74 antisera, raised mainly against strains of veterinary importance.

Immunoblotting.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out on whole-cell preparations of E. coli K-12 O26 (eae-positive and eae-negative strains) and O157 (eae-positive strains). NuPAGE 4 to 12% gels (Novex, San Diego, Calif.) were used, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. The bands were transferred onto nitrocellulose by overnight blotting at 30 mA. The nitrocellulose was blocked with 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Oxoid) in PTNE buffer (0.01 M PBS with 0.5% Tween 80 [vol/vol], 2 g of NaCl [wt/vol], 0.001 M EDTA), pH 7.2. Following incubation with biotinylated MAb dilutions at 37°C for 1 h, the nitrocellulose strips were washed in PTNE buffer before the addition of streptavidin peroxidase for a further 1 h. After another wash, the peroxidase substrate, 0.5 mg of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) per ml in 0.02 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.2, with 0.3 μl of H2O2 (30% solution) per ml (vol/vol), was added. After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the strips were washed with distilled water, which stopped any further reaction.

RESULTS

MAb-based sandwich ELISA.

Nine of the 430 hybridomas were selected as being reactive to OM preparations of E. coli strain 4276 and nonreactive to strain 1045. Three stable clones were derived from these, one of which was no longer reactive with strain 4276. Ascites fluid was prepared with the remaining two lines, MAbs 2F3 and 6G5, and used to prepare capture and biotinylated MAb reagents for use in sandwich ELISAs. Strain 4276 was used to optimize the assays.

Table 1 summarizes the sandwich ELISA results obtained with the collection of E. coli strains initially examined. The MAb 6G5 sandwich ELISA reacted only with the strain used to immunize the mouse for the hybridoma fusion. The MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA reacted positively with only three O26 strains containing eae and/or the VT virulence factors. Neither of the assays reacted with Salmonella arizonae, Salmonella kentucky, Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella flexneri, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida, Hafnia alvei, Serratia spp., Proteus vulgaris, Erwinia spp., Serratia liquefaciens, and Citrobacter freundii.

The sensitivity of detection for the MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA for strain 4276 was 105 CFU/ml.

Test samples.

The MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA was used to screen various groups of E. coli strains. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of 46 ELISA-positive and 42 ELISA-negative strains; these were largely from a collection of 216 strains isolated from animal enteritis cases in Northern Ireland but included two ELISA-positive bovine O111 strains from Belgium, 10 ELISA-negative Northern Ireland bovine O157 strains, and ELISA-negative O118 (n = 5), O5 (n = 2) O111 (n = 1), and O20 (n = 2) strains from Belgian cattle. The majority of the ELISA-positive strains were O26, although small numbers of other O-serotypes were evident. In addition, the majority of the ELISA-positive strains were either eae or eae and VT positive, with low numbers of eae- and VT-negative strains or strains only positive for VT. All of the O18 ELISA-negative and the majority of O26 ELISA-negative strains were eae and VT negative, whereas both the ELISA-negative O111 strains were eae and VT positive. Included in Table 2 are serotypes recognized as important causes of bovine enteritis: O5, O20, O111, and O118 (10), and bovine isolates of O157, all of which were positive for eae and/or VT.

TABLE 2.

Characterization of the E. coli strains demonstrating positive and negative reactions in the MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA

| Strain origin | ELISA | Total no. of isolates | No. eae positive | No. VT positive | No. eae and VT positive | No. eae and VT negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O26 | + | 33 | 10 | 3 | 18 | 2 |

| − | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |

| O18 | + | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| − | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| O111 | + | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| − | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| O157 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| − | 10 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| Others | + | 4a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| − | 9b | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

One each of O73, O113, O69, and UT.

Two of O5, five of O118, and two of O20.

Table 3 summarizes the ELISA results obtained with the remaining Belgian bovine strains examined, none of which was serotyped, but all of which were characterized for the presence of eae, and some for the presence of VT. Twenty-one of the 56 strains isolated from 0- to 10-week-old calves that had died with enteritis were ELISA-positive, and 35 were ELISA negative; both groups of these strains were entirely eae positive, with or without VT. Twenty-three out of 67 E. coli strains isolated from the intestinal contents of healthy 6-month-old calves, sampled at an abattoir, were ELISA positive and all contained one or both of the eae and VT virulence factors; 33 of the 44 ELISA-negative strains also contained these factors. The third set of Belgian strains tested were 190 eae-positive E. coli strains isolated from two ∼8-week-old calves with enteritis; out of these, 115 were ELISA positive and 78 were ELISA negative.

TABLE 3.

Characterization of Belgian ELISA-positive and -negative E. coli strains

| Strain origin | ELISA | Total no. of isolates | No. eae positive | No. VT positive | No. eae and VT positive | No. eae and VT negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calves, 0–10 wk old, dead from enteritis | + | 21 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| − | 35 | 19 | 0 | 16 | 0 | |

| Calves, 6 mo old, normal | + | 23 | 16 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| − | 44 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 11 | |

| Calves, 2–8 wk old, with enteritis | + | 115 | 115 | NT | NT | 0 |

| − | 78 | 78 | NT | NT | 0 |

From six E. coli strains isolated from children <6 months old, five were ELISA positive; these consisted of four O26 strains and one O111 strain, all of which contained the eae and VT virulence factors, as did the one ELISA-negative O111 strain.

The results of the field survey of mixed cultures from human and animal diarrhea cases are summarized in Table 4. ELISA-positive reactions were obtained with 7.1 to 11.2% of the cultures tested from bovine, porcine, ovine, and human origins; single cultures were also recorded positive for the 8 canine and 31 avian strains examined. Pure ELISA-positive strains were obtained from 12 of these mixed cultures; these consisted of two O8 strains, from human samples, and 10 O26 strains, one from an ovine sample and nine from bovine samples. Only six of these (one O8 and five O26 strains) retained their ELISA-positive activity on retesting following storage at −70°C. The single O8 strain and three of the O26 strains were PCR positive for both eae and the gene encoding VT, and the other two O26 strains were positive for only eae or only the gene encoding VT. The six strains that had lost their ELISA activity were PCR negative for these virulence factors.

TABLE 4.

Results obtained with the MAb 2F3 sandwich ELISA on field isolates from enteritis cases

| Strain origin | No. tested | No. ELISA positive (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine | 366 | 41 (11.2) |

| Porcine | 42 | 3 (7.1) |

| Ovine | 40 | 3 (7.5) |

| Canine | 8 | 1 (12.5) |

| Avian | 31 | 1 (3) |

| Other | 8 | 0 (0) |

| Human | 490 | 44 (9.2) |

| Total | 985 | 93 (9.4) |

Immunoblotting.

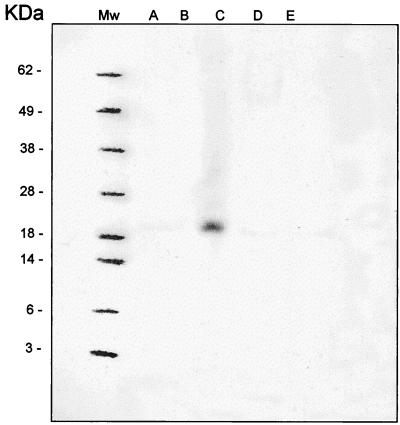

A strong immunoblot reaction was demonstrated at approximately 21 kDa for strain 4276 (O26, eae and VT positive), with MAb dilutions of up to 1:10,000 (Fig. 1). No immunoblot reactions were observed for K-12 or for strain 1045 (O26, eae and VT negative), S784 (O157, eae and VT positive), or 3680 (O157, eae positive and VT negative).

FIG. 1.

Nitrocellulose immunoblot with MAb 2F3 with whole-cell preparations of E. coli strains K-12 (A), 1045 (O26; eae and VT negative) (B), 4276 (O26; eae and VT positive) (C), S784 (O157; eae and VT positive) (D), and 3680 (O157; eae positive and VT negative) (E).

DISCUSSION

The MAb 2F3 produced in this study demonstrated a high level of specificity for a group of E. coli strains, in particular, strains of serotype O26, with the potential to express the EHEC and EPEC virulence factors of eae and VT. eae is the gene for the expression of intimin, which is regarded as a significant virulence factor in both EHEC and EPEC strains. If it is assumed that all strains with eae are potentially pathogenic, the application of MAb 2F3 in a sandwich ELISA format enables the rapid detection of a group of pathogenic strains from within these groups.

The identity of the antigen detected by MAb 2F3 is not clear. Immunoblotting demonstrated a strong reaction at 21 kDa with only the eae- and VT-positive O26 antigen used. From the molecular weight and surface presence of this protein, it is possible that it is fimbriae (14) or the recently described EspA protein (18). The former is indicated by the loss of antigen from six strains following storage, possibly from plasmid loss. Fimbriae implicated in early host cell adhesion of EPEC strains, named the bundle forming pili (bfp), have been defined as plasmid located (14). Giron et al. (15), using a molecular probe, demonstrated that bfp were only present in the EPEC strains of the human pathogenic E. coli strains that were examined. China et al. (9) failed to find bfp in animal EPEC or EHEC strains by using this human EPEC probe. Wieler et al. (36) demonstrated a significant increase in cell attachment of bovine EHEC O118 strains on fetal calf lung cells (90.5%) compared with human HEp-2 cells (52.4%) by using the fluorescent actin staining test (17). These studies indicate differences in adhesins between EPEC and EHEC strains. It is possible that the antigen detected in the present study is an alternative to bfp for preliminary cell attachment. If this is confirmed, since it was demonstrated in both human- and animal-isolated strains, it must be concluded that either there is a common host receptor or that these strains possess more than a single host cell attachment mechanism.

The loss of the antigen detected by the ELISA in six strains which did not possess either the eae or the VT factor and its presence in a small number of VT-positive and eae-negative isolates demonstrate its occurrence in non-EPEC and non-EHEC strains. It can be speculated that the presence of eae and/or VT provides some plasmid stability, but whether these strains are of any pathological significance is unknown and requires further investigation. Nonpathogenic strains, such as many VT-producing strains, can express a virulence factor(s). It is recognized that virulence is the result of a combination of factors which, individually, have limited pathogenic effect. Apart from experimental infection, the significance of these factors in bacterial strains is determined by their presence in combination with other factors, and by their more-common occurrence in strains isolated from diseased animals or humans. The association of the vast majority of E. coli strains that reacted with MAb 2F3 to the presence of the gene for intimin, which is regarded as a virulence factor of notable significance, is a strong indication of the importance of the antigen to which it reacts.

The association of MAb 2F3 with eae was in the presence or absence of VT factors.

Because MAb 2F3 associated with eae in the presence and absence of VT factors, the assay developed could not distinguish between EHEC and EPEC strains. This result indicates a close relationship between the strains detected from the two pathogroups. Whether the virulence differences of these groups are associated with the presence or absence of VT requires further investigation.

A number of eae-positive strains with or without VT did not react with MAb 2F3. These include a number of strains of recognized bovine (O118 and O5), rabbit (O103), and human (O157) pathogenicity. In addition, of the 10 eae- or eae- and VT-positive O111 strains examined, only eight were ELISA reactive. If the antigen targeted by this MAb is confirmed as making a significant contribution to the virulence of EHEC and EPEC strains, it could be concluded that these nonreactive strains possess antigenic variations of this factor.

The high prevalence of O26 strains amongst the positive reactants to this MAb indicates the probable significance of this serotype in animal enteritis in Northern Ireland. A number of O26 strains were also present in the ELISA-negative group, the majority of these being eae and VT negative. This indicates that other pathogroups of this serotype are of probable significance in this condition.

Although only a small number of strains from human diarrhea were tested, the demonstration, by ELISA, of a common antigen in bovine and human isolates could indicate a zoonotic risk of bovine strains to humans. The commonality of the MAb-detected antigen was also demonstrated in the results obtained with isolates from the field survey of human and animal enteritis (Table 4). The fact that strains from the same serotypes have been implicated in both bovine and human diseases (O26, O111, and O18) also supports these findings. The presence of a high percentage of EHEC and EPEC strains in both ELISA-positive and -negative groups isolated from healthy calves sampled at an abattoir (Table 4) indicates a significant potential for infection of susceptible cattle and for zoonotic transfer to humans.

The results of the survey conducted with nearly 1,000 animal and human enteric isolates demonstrated a significant presence of strains expressing the targeted antigen (Table 4), in particular from bovine, human, ovine, and porcine samples. Although only five EHEC-EPEC strains were purified from these samples by the limited method employed, the presence of a virulence-associated antigen was demonstrated in a high proportion of the mixed cultures. This finding indicates a significant pathogenic role of EHEC and EPEC strains in both human and animal enteric diseases and highlights the diagnostic potential of the assay developed. Further studies to develop MAbs to surface antigens of the eae-positive strains that were nonreactive to the O26 MAb in this study would clarify the significance of the antigens in terms of virulence and virulent-strain detection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Neill Brice is gratefully acknowledged, as is the help of our colleagues from the institute’s diagnostic laboratory. In addition, we are indebted to Vinciane Pirson for the work carried out at Liège.

The Department of Health (under grant DH Code 246) financially supported this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball H J, Madden R. Escherichia coli O157 in cattle in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland surveillance bulletin no. 8, food safety. Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Agriculture for Northern Ireland; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball H J, Kerr S, Mackie D P. Monoclonal antibody-based ELISAs. In: Kroll R G, Gilmour A, Sussman M, editors. New techniques in food and beverage microbiology. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Press; 1993. pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball H J, Finlay D, Burns L, Mackie D P. Application of monoclonal antibody-based sandwich ELISAs to detect verotoxins in cattle faeces. Res Vet Sci. 1994;57:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball H J, Finlay D, Mackie D P, Greer D, Pollock D, McNair J. Application of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting an inflammatory response antigen in subclinical mastitic milk samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1625–1628. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1625-1628.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco J, Gonzalez E A, Garcia S, Blanco M, Regueiro B, Bernadadez I. Production of toxins by Escherichia coli isolated from calves with diarrhoea in Galicia (north-western Spain) Vet Microbiol. 1988;18:297–311. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanter N, Hall G A, Bland A P, Hayle A J, Parsons K R. Dysentry in calves caused by atypical strain of Escherichia coli (S102) Vet Microbiol. 1986;36:149–159. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(86)90053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.China B, Pirson V, Mainil J. Typing of bovine attaching and effacing Escherichia coli by multiplex in vitro amplification of virulence-associated genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3462–3465. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3462-3465.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.China B, Pirson V, Mainil J. Prevalence and molecular typing of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli among calf populations in Belgium. Vet Microbiol. 1998;63:249–259. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.China B, Pirson V, Jacquemin E, Pohl P, Mainil J G. Pathotypes of bovine verotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolates producing attaching/effacing (AE) lesions in ligated intestinal loop assay in rabbits. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:311–316. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coia J E. Clinical, microbiological and epidemiological aspects of Escherichia coli O157 infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;20:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filip C, Fletcher G, Wulff J L, Earheart C F. Solubilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli by the ionic detergent sodium-lauryl sarcosinate. J Bacteriol. 1973;115:717–722. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.3.717-722.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galfre G, Milstein C. Preparation of monoclonal antibodies: strategies and procedures. Methods Enzymol. 1981;73B:3–46. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)73054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giammanco A, Maggio M, Giammanco G, Morelli R, Minelli F, Scheutz F, Caprioli A. Characteristics of Escherichia coli strains belonging to enteropathogenic E. coli serogroups isolated in Italy from children with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:689–694. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.689-694.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giron J A, Ho A S Y, Schoolnik G K. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1991;254:710–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1683004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giron J A, Donnenberg M, Martin W C, Jarvis K J, Kaper J B. Distribution of the bundle-forming pilus structure gene (bfp A) among enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1995;168:1037–1041. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann K, Titus G, Montibeller J, Finn F M. Avidin binding of carboxyl-substituted biotin and analogues. Biochemistry. 1982;21:978–984. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P A, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1991;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M, Nisan I, Neves B, Bain C, Wolff C, Dougan G, Frankel G. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine M M. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhoea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louie M, DeAzavedo J, Clarke R, Borczyk A, Lior H, Richter M, Brunton J. Sequence heterogeneity of the eae gene and detection of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli using serotype-specific primers. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:449–461. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mainil J G, Jacquemin E R, Kaeckenbeeck A E, Pohl P H. Association between the effacing (eae) gene and the Shiga-like toxin-encoding genes in Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:1064–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Denamur E, Milon A, Picard B, Cave H, Lambert-Zechovsky N, Loirat C, Goullet P, Sansonetti P J, Elion J. Identification of a clone of Escherichia coli O103:H2 as a potential agent of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in France. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:296–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.296-301.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCleery D R, Rowe M T. Development of a selective plating procedure for the recovery of Escherichia coli O157:H7 after heat stress. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:252–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinney M M, Parkinson A. A simple, non-chromatic procedure to purify immunoglobulins from serum and ascites fluid. J Immunol Methods. 1986;96:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammad A, Peiris J S M, Wijewanta E A, Mahalingam S, Gunasekara G. Role of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli in cattle and buffalo calf diarrhoea. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;26:281–283. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montenegro M A, Bulte M, Trumpf T, Aleksic S, Reuter G, Bulling E, Helmuth R. Detection and characterization of fecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1417–1421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1417-1421.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moxley R A, Francis D H. Natural and experimental infection with an attaching and effacing strain of Escherichia coli in calves. Infect Immun. 1986;53:339–346. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.339-346.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller U W, Hawes C S, Jones W R. Monoclonal antibody production by hybridoma growth in Freund’s adjuvant primed mice. J Immunol Methods. 1986;87:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orskov F, Orskov L. Serotyping Escherichia coli. In: Bergen T, editor. Methods in microbiology. Vol. 14. London, England: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 43–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoonderwoerd M, Clarke R C, Dreumel A A, Van Rawluk S A. Colitis in calves: natural and experimental infection with a verotoxin-producing strain of Escherichia coli O-111:MN. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52:484–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scotland S M, Smith H R, Cheasty T, Said B, Willshaw G A, Stokes N, Rowe B. Use of gene probes and adhesion tests to characterise Escherichia coli belonging to enteropathogenic serogroups isolated in the United Kingdom. Med Microbiol. 1996;44:428–443. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherwood D, Snodgrass D R, O’Brien A D. Shiga-like toxin production from Escherichia coli associated with calf diarrhoea. Vet Rec. 1985;116:217. doi: 10.1136/vr.116.8.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teh C Z, Wong E. Generation of monoclonal antibodies to human gonadotropin by a facile cloning procedure. J Appl Biochem. 1984;6:48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells J G, Shipman L D, Greene K D, Sowers E G, Green J H, Cameron D N, Downes F P, Martin M L, Griffin P M, Oscroff S M, Potter M E, Tauxe R V, Wachsmuth I K. Isolation of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and other Shiga-like-toxin-producing E. coli from dairy cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:985–989. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.5.985-989.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieler L H, Schwanitz A, Vieler E, Busse B, Steinruck H, Kaper J B, Baljer G. Virulence properties of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains of serogroup O118, a major group of STEC pathogens in calves. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1604–1607. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1604-1607.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wray C, McLaren I, Pearson G R. Occurrence of ’attaching and effacing’ lesions in the small intestine of calves experimentally infected with bovine isolates of verocytotoxic Escherichia coli. Vet Rec. 1989;125:365–368. doi: 10.1136/vr.125.14.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]