Abstract

Objective

Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury is common complication after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF). In the present study, we evaluated RLN function during ACDF surgery using intraoperative RLN monitoring with an electromyography-endotracheal tube (EMG-ET).

Methods

In the present study, we retrospectively compared the postoperative RLN injury outcomes between patients who had undergone ACDF with and without an EMG-ET at Vajira Hospital from March 2017 to March 2022.

Results

The analysis included 85 patients, 58 (68.2%) of whom had undergone surgery without an EMG-ET and 27 (31.8%) with an EMG-ET. Of the no EMG-ET group, 8 (13.8%) and 1 (1.7%) patient had developed immediate postoperative dysphagia and hoarseness, respectively, with complete recovery within 12 months. In the EMG-ET group, 2 (7.4%) and 1 (3.7%) patient had developed dysphagia and hoarseness, respectively, with complete recovery within 3 months for all 3 patients. Persistent postoperative RLN palsy had occurred in 5 patients (8.6%) without the EMG-ET but in none of the patients with the EMG-ET. The sensitivity and specificity for the use of intraoperative EMG-ET to detect a potential RLN injury were 67.0% and 96.0%, respectively. The use of an EMG-ET reduced the retractor time (P = 0.003), and a retractor time of <70 minutes was associated with a decreased incidence of postoperative RLN injury (odds ratio, 0.122; 95% confidence interval, 0.015–0.981; P = 0.048).

Conclusions

The use of an EMG-ET for RLN monitoring during ACDF surgery was helpful in detecting postoperative RLN injury with fair sensitivity and high specificity and resulted in a shorter retractor time, thereby significantly reducing the risk of postoperative RLN injury.

Key words: Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, Dysphagia, Electromyography-endotracheal tube, Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACDF, Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; BMI, Body mass index; CMAP, Compound muscle action potentials; EMG, Electromyography; ET, Endotracheal tube; IONM, Intraoperative neuromonitoring; PEEK, Polyetheretherketone; RLN, Recurrent laryngeal nerve

Introduction

At present, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has been widely used to treat many conditions, including cervical spondylosis, cervical spinal trauma, cervical disc herniation, and cervical spine ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in symptomatic patients with myelopathy or radiculopathy. This procedure has been reported to have good results and low postoperative complication rates. However, the incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury from ACDF surgery has ranged from <1% to >20%.1, 2, 3 The symptoms of RLN injury vary and can include hoarseness, singing issues, dysphagia, food and/or liquid aspiration, a weak cough, stridor, and airway obstruction resulting in life-threatening conditions.4 These RLN injuries can be persistent issues for a significant proportion of patients, even >5 years after ACDF surgery.5 Several studies have suggested that the causes of RLN palsy include direct RLN injury, RLN entrapment between retractors and the endotracheal tube (ET), and overstretching of the RLN during retraction using the cervical retractor.3,6, 7, 8 The RLN is a mixed motor and sensory nerve. The motor portion supplies all the intrinsic muscles of the larynx that affect normal vocal cord movement, except for the cricothyroid muscle. Normally, the RLN on the right side will originate from the vagus nerve and ascend along the tracheoesophageal groove. It will frequently bifurcate before entering the larynx where it innervates the vocalis and arytenoid muscles. Stimulated nerve fibers will release a compound action potential, which is the total of the nerve fiber impulses. The compound action potential traverses through the nerve to cause a waveform recordable by placing electrodes at the muscle belly. This is recorded as electromyography (EMG) potentials or compound muscle action potentials (CMAP). The CMAP are the summation of the group of muscle fiber action potentials that occurs with mechanical or electrical stimulation. This is one of many forms of intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM). Therefore, one method of IONM is EMG recordings of the CMAP. Therefore, the use of EMG-ET for intubation could be used intraoperatively to evaluate the activity of these muscles and detect RLN activity by direct contact of the exposed electrodes with the vocal cords (Figure 1). The detection of CMAP can be used to recognize and help evaluate RLN function during surgery.1 The RLN has been previously monitored with continuous EMG. Many studies have used the EMG-ET for thyroid surgery. A meta-analysis with >30,000 patients had reported the incidence of RLN palsy in patients who had undergone total thyroidectomy with and without IONM of the RLN.9 They reported that the incidence of RLN palsy was lower in the IONM group than in the non-IONM group.9 The use of EMG-ET during ACDF has not been widely used in low-to-middle income countries, and few studies have reported on the efficacy of EMG-ET or compared the results of ACDF surgery with and without the EMG-ET. Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed the use of EMG-ET during ACDF surgery, especially for reducing the incidence of postoperative RLN injuries by comparing the outcomes of ACDF surgery with and without the use of EMG-ET.

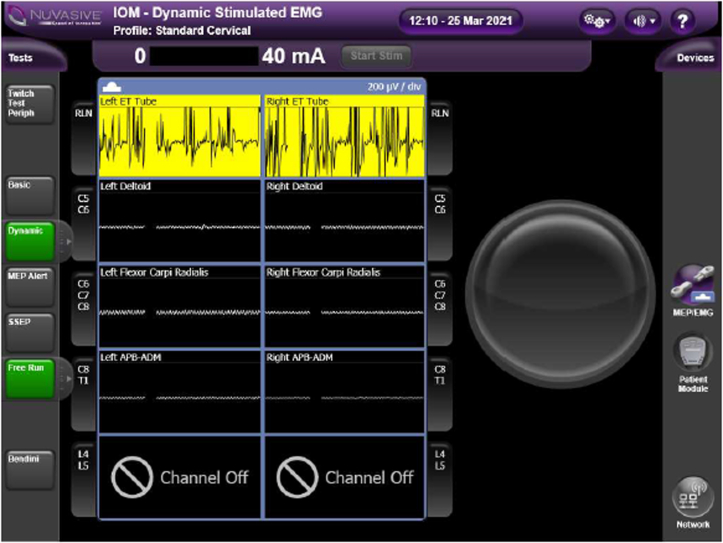

Figure 1.

Electromyography-endotracheal tube (EMG-ET) use for intubation with the design of the semirigid and curved polyvinyl chloride tube allowing for easier intubation. Bipolar electrodes are placed above the inflatable cuff, with an alignment gap of 2 cm. A laryngoscope should be used to verify that the EMG-ET has been positioned correctly. The alignment gap should be placed at the vocal cord level. The purple anterior midline, printed on the EMG-ET, should be aligned with the patient's anterior. The cuff should be inflated to prevent migration of the EMG-ET. The red and blue leads should be connected to a right and left monitoring channel for detection of the free-run EMG from the recurrent laryngeal nerve. ∗Bipolar electrodes.

Methods

The ethics committee of Vajira Hospital approved the present study (approval no. 070/65). All patients who had undergone ACDF at the neurosurgical department of Vajira Hospital from March 2017 to March 2022 were included. The ACDF indications included cervical spine injuries, cervical spondylosis, and cervical spine ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Patients with incomplete follow-up data, a history of hoarseness or dysphagia or symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux preoperatively, or a history of neck cancer or cervical spine tumor requiring radiotherapy after surgery were excluded.

Preoperative cervical spine radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging were performed for all patients. General anesthesia was administered without neuromuscular blockers or agents that affect neuromuscular monitoring. A laryngoscope was used to confirm the correct position of the EMG-ET in the group of patients for whom the EMG-ET had been used for intubation. The exposed electrodes were in contact with the vocal cords, and the gap in the anterior marker was positioned with the vocal cords. The EMG-ET was also positioned, with the purple line and anterior midline markings placed anteriorly. The electrode of the EMG-ET must be placed at the vocal cord level, and lubrication agents should not be used with the electrodes. IONM was performed by 2 certified neurophysiologists to evaluate the somatosensory-evoked potentials, transcranial motor-evoked potentials, and free-run EMG. A test series of 4 twitches was performed at the common peroneal nerve, with a response rate of ≥90% required before recording the EMG and RLN monitoring. The alarm criteria for significant RLN injury in the present cohort were sustained activity of >2 seconds from free-run EMG monitoring of the RLN.10 Continuous EMG sustained activity of >2 seconds, focal, semi-rhythmic tonic discharges, and an acute signal decrease in the RLN were considered significant signal alerts (Figure 2). A signal decrease was defined as the amplitude decreasing from >50% with a concordant latency increase of 5%. A loss of signal was defined as either a complete loss of amplitude or a decrease of the nerve amplitude to 100 μV after suprathreshold stimulation.11 A rescue protocol was followed. The rescue protocol included reversal of any antecedent surgical event, maintenance of the mean arterial blood pressure between 85 and 95 mm Hg, evaluation of the monitor leads, determination of whether the neuromuscular blockade had been given, monitoring the mean arterial blood pressure, evaluation of the cervical retractor blade position, pausing any surgical actions, and waiting for resolution of the silent signal from IONM before continuing surgery. If the IONM alert persisted after performing the rescue protocol, we recorded it as an IONM alarm in the present cohort.

Figure 2.

Free-run electromyography (EMG) monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) showing continuous sustained activity of >2 seconds. The rescue protocol was followed. If the rescue protocol was followed but the intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring alert persisted, it was recorded as an intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring alarm. IOM, intraoperative monitoring.

Surgery was performed for all patients via an anterior cervical approach from the right side using the Smith-Robinson technique. Both surgeons were experienced spinal neurosurgeons with >5 years of experience, and IONM was performed by 2 certified neurophysiologists. Dissection was performed through the platysma, and avascular planes were created between the carotid and visceral sheaths. Dissection was maintained medial to the carotid sheath and lateral to the tracheoesophageal groove. Subperiosteal dissection of the longus colli muscles was performed on both sides of the vertebral bodies. A self-retained cervical retractor system was placed within these planes under the longus colli muscles for prevertebral soft tissue retraction. The RLN was not visualized during surgery in any of the patients. The retractor time was recorded after cervical retractor application. We reduce the ET pressure every 30 minutes during cervical retractor application in the group without the EMG-ET. However, we did not reduce the ET pressure in the patients who had undergone surgery with the EMG-ET. Osteophyte removal and discectomy with a high-speed drill, curettes, and Kerrison rongeurs were performed under a microscope. After fusion bed preparation, interbody fusion was performed with a polyetheretherketone (PEEK) cage. All PEEK cages were filled with bone graft substitutes. The surgical wound was closed with an intradermal absorbable suture, with placement of a low-pressure drain. Finally, the PEEK cage positions were checked using fluoroscopy. A soft collar was applied for 6 weeks after surgery for all patients.

Postoperative Evaluation

All the patients had undergone a physical examination at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. The operative time (including the IONM setup time), blood loss, retractor time, and complications were recorded. On the first postoperative day, laryngoscopy was performed to evaluate vocal cord mobility. A voice rating scale was used to evaluate hoarseness.12 Dysphagia was evaluated using the Bazaz grading system.13 An otolaryngologist who was unaware of the treatment protocol was consulted for further management in the case of postoperative RLN palsy found by laryngoscopy, dysphagia development, and hoarseness.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using Stata Statistics/Data Analysis for Windows, version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, median and interquartile range, or frequencies and percentages. The differences between the 2 groups was tested using the Pearson χ2 test, Fisher exact test, independent sample t test, or Mann-Whitney U test. The associated risk factor for complications and RLN injury was tested using a logistic regression test. A P value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

The present study included 89 patients who had undergone ACDF at 145 intervertebral disc levels. Of the 89 patients, 4 were excluded because of vertebral metastasis in 3 who had required radiotherapy after surgery and incomplete follow-up data for 1 patient. Thus, the present analysis included 85 patients. The demographic and perioperative parameters are shown in Table 1. Of the 85 patients, 58 (68.2%) had undergone surgery without the EMG-ET and 27 (31.8%) with the EMG-ET. Three patients had had a history of previous ACDF surgery on the right side of the neck. Of the 85 patients, 51 were men and 34 were women, with a mean age of 55.4 ± 14.8 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) and median length of hospital stay were 24.1 ± 4.6 kg/m2 and 7 days (interquartile range, 5–11 days), respectively. The most common indications for ACDF were spondylosis (53.0%) and trauma (37.7%). Most patients had undergone single-level ACDF (55.3%), and the most common level of ACDF was C5-C6 (65.9%). The operative time in the EMG-ET group was longer than that in the no EMG-ET group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.296). The retractor time between the 2 groups was significantly different (P = 0.003) and was lower in the EMG-ET group.

Table 1.

Demographic and Perioperative Parameters

| Parameter | EMG-ET |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Patients | 58 (68.24) | 27 (31.76) | |

| Sex | 0.479 | ||

| Male | 33 (56.90) | 18 (66.67) | |

| Female | 25 (43.10) | 9 (33.33) | |

| Age (years) | 54.34 ± 13.82 | 57.70 ± 16.62 | 0.331 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.83 ± 4.62 | 24.64 ± 4.68 | 0.456 |

| Length of stay (days) | 7.00 (6.00–11.00) | 7.00 (5.00–11.00) | 0.337 |

| Diagnosis | 0.205 | ||

| Trauma | 21 (36.21) | 11 (40.74) | |

| Spondylosis | 33 (56.90) | 12 (44.44) | |

| OPLL | 4 (6.90) | 2 (7.41) | |

| Infection | – | 2 (7.41) | |

| Underlying disease | 0.003 | ||

| None | 44 (75.86) | 11 (40.74) | |

| Osteoporosis | 1 (1.72) | – | |

| Type 2 DM | 1 (1.72) | 4 (14.81) | |

| Tumor | 3 (5.17) | 1 (3.70) | |

| Other | 9 (15.52) | 11 (40.74) | |

| Previous ACDF surgery | 1 (1.72) | 2 (7.41) | 0.236 |

| Operation time (minutes) | 176.50 (120.00–250.00) | 215.00 (165.00–290.00) | 0.296 |

| Retraction time (minutes) | 125.00 (85.00–180.00) | 60.00 (50.00–110.00) | 0.003 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 50.00 (20.00–100.00) | 100.00 (50.0–200.00) | 0.046 |

| Complication | 0.278 | ||

| None | 44 (75.86) | 24 (88.89) | |

| Dysphagia | 8 (13.79) | 2 (7.41) | |

| Hoarseness | 1 (1.72) | 1 (3.70) | |

| RLNP | 5 (8.62) | – | |

| Fused level | |||

| C3-C4 | 9 (15.52) | 6 (22.22) | 0.544 |

| C4-C5 | 26 (44.83) | 9 (33.33) | 0.316 |

| C5-C6 | 40 (68.97) | 16 (59.26) | 0.380 |

| C6-C7 | 19 (32.76) | 10 (37.04) | 0.699 |

| Fused levels (n) | 0.851 | ||

| 1 | 31 (53.45) | 16 (59.26) | |

| 2 | 16 (27.59) | 8 (29.63) | |

| 3 | 8 (13.79) | 3 (11.11) | |

| 4 | 3 (5.17) | – | |

Data presented as n (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range).

EMG-ET, electromyography endotracheal tube; BMI, body mass index; OPLL, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament; DM, diabetes mellitus; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; RLNP, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

Postoperative RLN injury complications had occurred in both groups (Table 2). In the no EMG-ET group, immediate postoperative dysphagia and hoarseness had developed in 8 (13.8%) and 1 (1.7%) patient, respectively, with complete recovery within 12 months. In contrast, in the EMG-ET group, 2 (7.4%) and 1 (3.7%) patient had developed dysphagia and hoarseness, respectively, with complete recovery within 3 months. Persistent postoperative RLN palsy occurred in 5 patients (8.6%) without EMG-ET and none of the patients with EMG-ET. The mean retraction time in the RLN injury group was 110 minutes compared with 100 minutes for those with no RLN injury.

Table 2.

Postoperative Complications

| Complication | Total (n; %) | EMG-ET (n; %) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| None | 68 (80.00) | 44 (75.86) | 24 (88.89) | 0.162 |

| Dysphagia | 10 (11.76) | 8 (13.79) | 2 (7.41) | 0.492 |

| Complete recovery | ||||

| Within 3 months | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Within 12 months | 2 | 2 | – | |

| Hoarseness | 2 (2.35) | 1 (1.72) | 1 (3.70) | 0.537 |

| Complete recovery | ||||

| Within 3 months | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Within 12 months | – | – | – | |

| RLNP | 5 (5.88) | 5 (8.62) | – | 0.173 |

| Complete recovery | ||||

| Within 3 months | – | – | – | |

| Within 12 months | – | – | – | |

EMG-ET, electromyography endotracheal tube; RLNP, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

Alarm IONM was found for 3 patients after the rescue protocol. Only 1 patient had had a false-positive alarm. Also, 1 patient had had a false silent alarm. The sensitivity and specificity of intraoperative EMG-ET to detect a potential RLN injury was 67.0% and 96.0%, respectively. The positive predictive value was 67.0%, and the negative predictive value was 96.0%. The positive predictive value referred to the likelihood of RLN injury after surgery with an IONM alarm. The negative predictive value referred to the likelihood of the RLN remaining intact after surgery with silent IONM. Significant associations between the fused level at C3-C4 with RLN injury (P = 0.034) and between a retractor time of >70 minutes and RLN injury (P = 0.032) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistically Significant Connection Between RLN Injury and Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | RLN Injury |

|---|---|

| Sex (Female) | 0.273 |

| Age >60 years | 0.834 |

| Higher BMI | 0.275 |

| History of previous ACDF surgery | 0.101 |

| IONM | 0.162 |

| Fused level | |

| C3-C4 | 0.034 |

| C4-C5 | 0.270 |

| C5-C6 | 0.109 |

| C6-C7 | 0.067 |

| Higher no. of fused levels | 0.566 |

| Operative time >185 minutes | 0.745 |

| Retractor time >70 minutes | 0.032 |

| Blood loss >75 mL | 0.179 |

RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; BMI, body mass index; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; IONM, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring.

Univariate analysis was performed to assess the risk factors for postoperative RLN injury. A model was generated using the factors identified on univariate analysis as potential risk factors. These included age, BMI, ACDF level, operative time, and retractor time (Table 4). A retractor time of >70 minutes was associated with postoperative RLN injury (odds ratio [OR], 8.177; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.020–65.578; P = 0.048). Every BMI increase of 1 kg/m2 was potentially associated with this complication but the difference was not statistically significant (OR, 1.118; 95% CI, 0.999–1.250; P = 0.051). A subgroup postoperative complication analysis revealed that every BMI increase of 1 kg/m2 resulted in a significantly increased risk of 39.7% for postoperative hoarseness (OR, 1.397; 95% CI, 1.074–1.816; P = 0.013), and intraoperative blood loss of >75 mL resulted in a significantly increased risk of postoperative dysphagia (OR, 8.999; 95% CI, 1.080–74.975; P = 0.042).

Table 4.

Risk Factors for Postoperative RLN Injury

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.935 | 0.662–5.655 | 0.228 |

| Older age | 1.011 | 0.974–1.049 | 0.555 |

| Higher BMI | 1.118 | 0.999–1.250 | 0.051 |

| Previous ACDF surgery | 8.933 | 0.760–105.074 | 0.082 |

| Fused level | |||

| C3-C4 | – | – | – |

| C4-C5 | 0.528 | 0.167–1.663 | 0.275 |

| C5-C6 | 2.889 | 0.757–11.027 | 0.121 |

| C6-C7 | 2.700 | 0.912–7.997 | 0.073 |

| No. of fused levels | |||

| 2 | 2.007 | 0.627–6.425 | 0.240 |

| 3 | 1.083 | 0.196–5.993 | 0.927 |

| Longer operative time | 0.997 | 0.991–1.003 | 0.400 |

| Retractor time >70 minutes | 8.177 | 1.020–65.578 | 0.048 |

| Retractor time <70 minutes | 0.122 | 0.015–0.981 | 0.048 |

| Blood loss >75 mL | 0.417 | 0.132–1.311 | 0.134 |

RLN, recurrent laryngeal nerve; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to determine the use of EMG-ET during ACDF surgery to decrease the incidence of postoperative RLN injuries. Many studies have reported an incidence of RLN palsy and permanent RLN palsy after ACDF surgery of 0.2%–24% and 0.5%–4%, respectively.8,14,15 The incidence of postoperative dysphagia, hoarseness, and RLN palsy complications in the present study is shown in Table 2. The incidence for all complications was lower in the EMG-ET group than in the no EMG-ET group in the early postoperative period. No patient in the EMG-ET group had experienced postoperative permanent RLN palsy compared with the no EMG-ET group. In the latter group, persistent RLN palsy complications had developed in 5 patients (3.40%). We believe that using EMG-ET during ACDF surgery could decrease the incidence of postoperative RLN injury.

Furthermore, fusion at the C3-C4 level was significantly associated with RLN injury (P = 0.034; Table 3). This might have been because the C3-C4 vertebrae have a close angle to the mandible, the tracheoesophageal structures are more fixed at higher levels, and retraction is likely with more compression. In addition, it can be difficult to correctly place the retractor blade in the proper position, resulting in more force to nearby soft tissue and causing RLN injury. Moreover, the C3-C4 vertebrae are near the proximal superior laryngeal nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, and hypoglossal nerve; thus, the retractor blade could directly compress these nerves, resulting in postoperative dysphagia.

Dimopoulos et al.16 reported that intraoperative EMG-ET monitoring was characterized by high sensitivity and specificity in detecting RLN injuries. Their findings differed from our findings because EMG-ET could detect postoperative RLN injury with fair sensitivity (67%) and high specificity (96%). We found that EMG-ET can detect RLN injury with fair sensitivity; thus, surgeons should use it carefully in the case of positive results. The cuff size selection for the EMG-ET is only available in 7.0 and 8.0. The limited size choices have made it difficult to choose the right size for each patient. In the present cohort, 1 patient had had a false-positive RLN stimulation, which might have resulted from the EMG-ET having been dislodged from the previous correct position during surgery and stimulation coming from distal part of injury. In addition, 1 patient had had a false-negative RLN stimulation, which might have resulted from rotation of the EMG-ET during surgery by the anesthesiologist. We would recommend that the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and neurophysiologist check the position of the EMG-ET when IONM has resulted in an abnormal alarm signal.

Jellish et al.3 reported that a prolonged intubation time with elevated ET pressure could increase the incidence of postoperative hoarseness and sore throat. In the present cohort, the EMG-ET group had had a shorter retraction time with a statistically significant difference, although the operative time was slightly longer (Table 2). Performing surgery with the EMG-ET means that the surgeon does not need to reduce the ET pressure and interrupt the retractor period every 30 minutes. The surgeon can perform a smooth operation without concern for the cervical retractor pressing on the RLN for too long because the EMG-ET can monitor the integrity of RLN with fair sensitivity and high specificity. The operative time was longer for the EMG-ET group than for the no EMG-ET group because of the time required to set up the IONM and to wait for a train of 4 twitches with a response rate of ≥90% before recording the EMG for RLN monitoring and applying the cervical retractor. The data presented in Table 3 showed that a retractor time >70 minutes was associated with postoperative RLN injury (OR, 8.177; 95% CI, 1.020–65.578; P = 0.048). However, we found no association between the operative time and the incidence of postoperative RLN injury complications. We have concluded that the use of EMG-ET could significantly reduce the retractor time, thereby reducing the risk of postoperative RLN injury.

In the present cohort, only 3 patients (11.11%) had developed postoperative dysphagia and hoarseness during surgery with EMG-ET and had completely recovered within 3 months compared with 14 patients (24.14%) who had undergone surgery without EMG-ET. Perioperatively, during dissection and the cervical retractor time under the longus colli muscle, sustained EMG activity >2 seconds from free-run EMG monitoring of the RLN after the rescue protocol had occurred. This might have occurred in the patient with previous ACDF surgery and a diagnosis of morbid obesity because of massive scar tissue from previous surgery, a short neck, the amount of fat that had increased the thickness of the prevertebral soft tissue, and the deeper approach required to the anterior vertebrae when applying the cervical retractor. It could have resulted from the greater retraction force compared with that required for nonobese patients, with greater retraction of the RLN and esophagus causing an IONM synchronous alarm and postoperative neurapraxia of the RLN.

Several studies have concluded that repeat ACDF surgery and obesity carries a greater potential for postoperative RLN injury and dysphagia after ACDF procedures.17,18 Those findings have corresponded with our findings, with previous ACDF surgery and obesity associated with the early postoperative complication of dysphagia. We would recommend that for morbidly obese patients and those with previous anterior cervical surgery, the surgeon might use extension of the neck to create more lordosis and use more meticulous rostrocaudal dissection of the longus colli muscle around the surgical site to create more space to apply the cervical retractor and decrease the retraction force. In our cohort, a greater BMI and a history of previous ACDF surgery were potential factors associated with the occurrence of dysphagia (OR, 1.118; 95% CI, 0.999–1.250; P = 0.051; and OR, 8.933; 95% CI, 0.760–105.074; P = 0.082, respectively; Table 4). We believe that the use EMG-ET is advised for patients with morbid obesity and a history of previous ACDF surgery.

The present study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a small number of patients. The present study was performed at a single institute in a middle-income country. Although using EMG-ET during surgery was safe, not all patients can afford this instrument because the cost of EMG-ET is expensive. Also, we could not compare the outcomes with surgery from the left side of the neck. All the patients in the present study had undergone surgery from the right side owing to surgeon preference because an approach from the left side is more difficult for right-hand surgeons. Using the Bazaz grading system to analyze the dysphagia outcomes in this cohort might not have been accurate owing to the different perceptions of each patient. Many studies have suggested more objective data to evaluate dysphagia, such as a barium swallowing study.19,20 Moreover, we could not control for several factors such as complications from anesthesia. Unrecognized intraoperative hypotension or hypothermia from anesthetic agents could have affected the IONM. Additional studies should be focus on the cost-effectiveness of the use EMG-ET in ACDF surgery, and a randomized controlled trial might be useful.

Conclusions

The use of EMG-ET for RLN monitoring during ACDF surgery was helpful in detecting postoperative RLN injury with fair sensitivity and high specificity and could shorten the retractor time. We found a tendency for the patients who had undergone ACDF surgery with EMG-ET to have a decreased incidence of postoperative of RLN injuries, including hoarseness, dysphagia, and RLN palsy.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nattawut Niljianskul: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation, Visualization. I-Sorn Phoominaonin: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Alongkorn Jaiimsin: Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants who contributed to the present study and all staff at the Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, for their contribution.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that the article content was composed in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pearlman R.C., Isley M.R., Ruben G.D., et al. Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve using acoustic, free-run, and evoked electromyography. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22:148–152. doi: 10.1097/01.wnp.0000158464.82565.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutler W.J., Sweeney C.A., Connolly P.J. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury with anterior cervical spine surgery: risk with laterality of surgical approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1337–1342. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jellish W.S., Jensen R.I., Anderson D.E., et al. Intraoperative electromyographic assessment of recurrent laryngeal nerve stress and pharyngeal injury during anterior cervical spine surgery with Caspar instrumentation. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(suppl 2):170–174. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.91.2.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheahan P., O’Connor A., Murphy M.S. Risk factors for recurrent laryngeal nerve neuropraxia post thyroidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:900–905. doi: 10.1177/0194599812440401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue W.M., Brodnew W., Highland T.R. Persistent swallowing and voice problems after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:677–682. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apfelbaum R.I., Kriskovich M.D., Haller J.R. On the incidence, cause, and prevention of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsies during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2906–2912. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audu P., Artz G., Scheid S., et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after anterior cervical spine surgery: the impact of endotracheal tube cuff deflation, reinflation, and pressure adjustment. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:898–901. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung A., Schramm J., Lehnerdt K., et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy during anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:123–127. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pardal-Refoyo J.L., Ochoa-Sangrador C. Bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in total thyroidectomy with or without intraoperative neuromonitoring: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2016;67:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan C.D., Uribe J.S. In: Youmans & Winn Neurological Surgery. 8th ed. Winn H.R., editor. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2022. Electrophysiologic studies and monitoring; pp. 2427–2436. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priya S.R., Garg S., Dandekar M. Intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in surgeries for thyroid cancer: a review. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021;7:70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin M.R., Koufman J.A. Endoscopic arytenoid repositioning for unilateral arytenoid fixation. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:44–47. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazaz R., Lee M.J., Yoo J.U. Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2453–2458. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gokaslan Z.L., Bydon M., De la Garza-Ramos R., et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after cervical spine surgery: a multicenter AOSpine clinical research network study. Glob Spine J. 2017;7(suppl):53S–57S. doi: 10.1177/2192568216687547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosdal C. Cervical osteochondrosis and disc herniation: eighteen years’ use of interbody fusion by Cloward’s technique in 755 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1984;70:207–225. doi: 10.1007/BF01406650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimopoulos V.G., Chung I., Lee G.P., et al. Quantitative estimation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve irritation by employing spontaneous intraoperative electromyographic monitoring during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:1–7. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31815ea8b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Roman R.J., McCarthy D., Luther E.M., et al. Effects of body mass index on perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery. Neurospine. 2021;18:79–86. doi: 10.14245/ns.2040236.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erwood M.S., Hadley M.N., Gordon A.S., Carroll W.R., Agee B.S., Walters B.C. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury following reoperative anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25:198–204. doi: 10.3171/2015.9.SPINE15187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang S.H., Kim D.K., Seo K.M., Lee S.Y., Park S.W., Kim Y.B. Swallowing function defined by videofluoroscopic swallowing studies after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a prospective study. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:2020–2025. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frempong-Boadu A., Houten J.K., Osborn B., et al. Swallowing and speech dysfunction in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a prospective, objective preoperative and postoperative assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:362–368. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]