Abstract

Objectives

The clinical professor track has expanded and reflects a trend toward hiring non–tenure-track faculty in public health; however, little is known about this track. We documented characteristics of clinical faculty at US schools of public health.

Methods

We surveyed clinical faculty at Council on Education for Public Health–accredited schools of public health in the United States in 2019, identified via each school’s website. We invited faculty (n = 264) who had the word clinical in their title (ie, apparently eligible faculty), had a working email address, and were not authors of this article to provide information about their rank, degree credentials, expectations for teaching, service, research and practice, and promotion criteria at their institution. In addition, we used open-ended responses to explain and contextualize quantitative data.

Results

Of 264 apparently eligible faculty surveyed, 88 (33.3%) responded. We included 81 eligible clinical faculty in our final sample, of whom 46 (56.8%) were assistant professors and 72 (88.9%) had a terminal degree; 57 of 80 (71.3%) had an initial contract of ≤2 years or no contract. Most clinical faculty listed service (96.2%), teaching (95.0%), and student advising/mentoring (86.3%) as duties; fewer clinical faculty reported research (55.0%), practice (33.8%), or clinic (7.5%) duties. Only 37.1% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that promotion policies for clinical track faculty were clear.

Conclusions

If most clinical faculty are at the lowest academic rank, with short contracts and unclear expectations, it will be difficult for clinical faculty to advance and challenging for schools of public health to benefit from this track. Clear institutional expectations for scope of work and promotion may enhance the contribution of clinical faculty to schools of public health and help define this track.

Keywords: clinical track faculty, non–tenure-track faculty, promotion, public health practice, schools of public health

Academic public health, from its origins in the 1915 Welch–Rose Report, 1 has emphasized the dual role of schools of public health as sites for the production of scholarly research and training grounds for public health practitioners. Tenure-track faculty working in schools of public health often focus on the former, because scholarship is heavily merited for faculty on tenured tracks. Although a research focus is critical to advancing public health knowledge, it may result in reduced emphasis on teaching and diminished connections to community-based public health efforts. 2

In higher education, the clinical professor track was established to ensure that students would be oriented to practice in their respective fields. 3 Accreditation bodies for professional fields require students to engage in experiential work to be workforce-ready upon graduation, 4 and it is crucial that instructors understand how to provide opportunities to gain translational knowledge and skills. Thus, clinical professors can bridge the gap of theory to practice for students in professional degree programs. Aside from their role in teaching, clinical faculty across disciplines are currently engaged in clinical practice, community-oriented practice, scholarship, and administration. 5,6

Non–tenure-track faculty positions, such as clinical track faculty, are on the rise as tenure-track positions steadily decline in the United States. 7,8 Clinical faculty positions that involve patient care, such as medicine, nursing, and social work, are established and fairly standardized, 5 yet little is known about the clinical track in public health. The presence of clinical faculty in US schools of public health was documented only recently; a 2019 analysis identified that 10% of faculty from schools of public health are clinical, and clinical faculty work in more than half of all US schools of public health. 9

Despite the broad presence of clinical faculty, the motivations for hiring them, as well as their roles, duties, and practice activities, are unclear. Learning about why faculty are hired and what their role and duties, including practice activities entail, will provide insight into how schools are meeting their educational and practice missions. Furthermore, the training, employment terms, and promotion criteria for the clinical track have not been described. Understanding the training, employment terms, and promotion criteria for the clinical track will be a crucial first step in improving the transparency of this track and evaluating its role in public health education.

We describe characteristics of clinical public health faculty, including their rank and degree credentials; demands for teaching, practice, and other activities; clarity of expectations for practice and promotion; and their appointment terms, such as salary coverage, length of employment contracts, tenure options, and promotion policies. We collected data through a nationwide survey of clinical faculty in public health.

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

Our source population was clinical faculty in Council on Education for Public Health–accredited schools of public health in the United States. In July and August 2019, we identified such faculty by reviewing the websites of all 60 US schools of public health, some of which are colleges of public health (we did not review programs of public health). 9 We included only schools of public health as a first step in understanding the clinical track in institutional settings with a strong public health focus. More than half of schools employed at least 1 clinical faculty member. 9 In this study, we included faculty listed on each institution’s website who had the word clinical in their title (ie, apparently eligible faculty), had a working email address, and were not authors of this article. Our interest was in studying faculty whose primary employment and appointment was as a clinical faculty member in a school of public health, rather than adjunct or other faculty who have a clinical title but work full-time in another institution. Because our investigation was intended as a first step in understanding the clinical track, our review excluded tenure-track, research, and practice faculty; visiting and emeritus faculty; instructors; lecturers; adjuncts; and faculty with joint appointments if their primary appointment was not clinical or was outside public health (eg, faculty with a primary appointment in a medical school).

We sent an invitation to join the study in November 2019. Two weeks after the initial invitation, we sent an email reminder to complete the survey. Of 327 apparently eligible clinical faculty, we had working email addresses for 273 people. We emailed 269 apparently eligible faculty after removing all 4 authors from the list. After sending the initial email, we found that 4 people were not eligible and 1 person had retired, leaving 264 apparently eligible faculty who received a survey.

Survey Questionnaire

Our anonymous online questionnaire, administered via Qualtrics in November 2019, asked participants about their rank, degree credentials, amount of time on the clinical track at their current institution, whether their salary was covered by hard funds (ie, guaranteed salary) or soft funds (ie, the faculty member must cover their salary), the length of their employment contract, and whether their position was on a tenure track.

An open-ended question asked how practice was defined in the participant’s unit for clinical faculty. In addition, we asked participants to identify duties they were expected to perform, with checkboxes for research, teaching, service, practice, clinic, and student advising/mentoring; a checkbox for “I don’t know/the expectations are unclear”; and an open-ended area for adding duties. Another open-ended question asked participants to describe their practice.

We asked participants to what extent they agreed with the following 2 statements: “The expectations for what my practice entails are clear to me” and “The policies for my promotion are clear to me.” Responses were on a 6-point Likert-type scale, where 6 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree. We also asked how many credits each respondent taught per academic year. A copy of the full survey is available upon request.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize rank, highest degree held, and other quantitative data. We used the Kruskal–Wallis and Pearson χ2 tests to compare outcome variables by rank, number of years a respondent was employed at their institution, highest degree the respondent had earned, their salary coverage, and teaching load. We considered P < .05 to be significant. We used SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp) for statistical analysis. Using a parallel mixed-design approach, 10 we reviewed the open-ended responses for quotes to support interpretation and explanation of quantitative survey data. 11 The University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board designated this study as exempt.

Results

Clinical Faculty Characteristics

Of 264 apparently eligible faculty surveyed, 88 (33.3%) responded. We included in the analysis respondents who categorized their rank as assistant professor, associate professor, or full professor, and we excluded 7 respondents who categorized their rank as “other,” for a final sample of 81 respondents.

Forty-six of 81 (56.8%) respondents were clinical professors at the assistant rank (eg, clinical assistant professors, assistant clinical professors), 25 (30.9%) clinical faculty were associate professors, and 10 (12.3%) clinical faculty were full professors.

Most of the 81 respondents (n = 72; 88.9%) reported having a terminal degree; 53 had a doctor of philosophy degree, 7 had a doctor of medicine degree, and 13 had another degree (4 had a doctor of public health; 3 had a doctor of education; 2 had a doctor of physical therapy; and 1 each had a doctor of health science, doctor of occupational therapy, doctor of psychology, and doctor of audiology degree). Nine (11.1%) respondents without a doctoral degree reported a master’s degree as their highest degree.

Thirty-five of 80 (43.8%) faculty members indicated being on the clinical track for 0-3 years. Of 46 assistant professors, 8 (17.4%) reported being on the clinical track for ≥7 years, 9 (19.6%) for 4-6 years, and 29 (63.0%) for 0-3 years. Of 25 associate professors, 17 (68.0%) reported being on the clinical track for ≥7 years, 3 (12.0%) for 4-6 years, and 5 (20.0%) for 0-3 years. Of 9 full professors, 7 reported being on the track for ≥7 years, 1 for 4-6 years, and 1 for 0-3 years.

Appointment Terms of Clinical Faculty

Forty-seven of 80 (58.8%) respondents reported an initial contract of ≤1 year, and 3 (3.8%) reported having no contract (Table). Three respondents reported being on a tenure track. Of 79 respondents, 59 (74.7%) reported receiving 100% guaranteed (or “hard”) salary, 6 (7.6%) reported generating 100% of their salary (“soft money”), and 14 (17.7%) reported receiving a mix of soft money and hard salary.

Table.

Appointment terms of clinical faculty survey a respondents from schools of public health at institutes of higher education, United States, 2019 (N = 81)

| Appointment terms | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Length of initial contract, y b | |

| No contract/no limit | 3 (3.8) |

| ≤1 | 47 (58.8) |

| 2 | 7 (8.8) |

| 3 | 20 (25.0) |

| 4 | 0 |

| 5 | 3 (3.8) |

| >5 | 0 |

| Tenure track | |

| Yes | 3 (3.7) |

| No | 78 (96.3) |

| Expected dutiesb,c | |

| Service | 77 (96.2) |

| Teaching | 76 (95.0) |

| Student advising/mentoring | 69 (86.3) |

| Research | 44 (55.0) |

| Practice | 27 (33.8) |

| Other d | 14 (17.5) |

| Clinic | 6 (7.5) |

| Do not know/the expectations are unclear | 3 (3.8) |

| Teaching load per academic year, no. of creditsb,e | |

| 0-3 | 12 (15) |

| 4-6 | 19 (23.8) |

| 7-9 | 13 (16.3) |

| 10-12 | 15 (18.8) |

| ≥13 | 21 (26.3) |

aBased on a website review of schools of public health in the United States, 264 faculty were invited to participate in the survey using the following criteria: designated as a clinical faculty on the website, had a working email address, and were not authors of this article.

bOf 80 respondents.

cCategories not mutually exclusive.

dOf the 14 respondents who reported “other,” 11 described administrative duties.

eOne credit may not be uniform in course length and workload across institutions.

Of 80 respondents, nearly all reported service (n = 77, 96.2%) and teaching (n = 76, 95.0%) duties (Table), most respondents reported student advising/mentoring duties (n = 69, 86.3%) and research (n = 44, 55.0%), and 27 (33.8%) reported practice duties. Of the 14 (17.5%) respondents who reported “other” duties, 11 indicated administrative duties. Six respondents reported clinical duties, and 3 respondents did not know what duties were expected of them.

The teaching load per academic year varied among respondents. Thirty-six of 80 (45.0%) clinical faculty reported teaching ≥10 credits (Table).

Defining Clinical Faculty Practice

Of 70 respondents to the question, “How is practice of a clinical track faculty defined at your unit?,” 19 (27.1%) indicated that practice is not defined or self-defined in their institution/unit; 18 (25.7%) said that practice is considered primarily teaching but can include other activities; 9 (12.9%) indicated that practice is considered some combination of teaching, scholarship, service, and/or administration; 8 (11.4%) reported that the practice designation is for non–tenure-track faculty; and 4 (5.7%) reported working as a clinician.

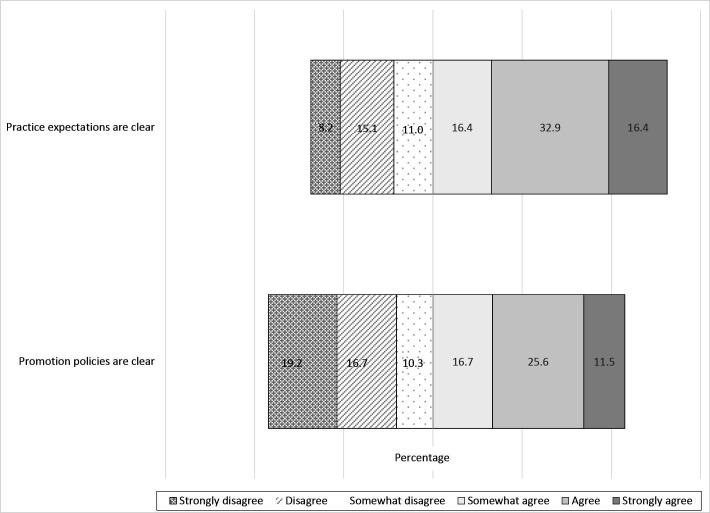

Twenty-five of 73 (34.3%) respondents strongly disagreed, disagreed, or somewhat disagreed with the statement, “The expectations for what my practice entails are clear to me” (Figure). One respondent suggested a lack of standardization in the track even within their own institution, stating in an open-ended response, “Practice is not defined at our college of public health. If you have seen one clinical track faculty member’s practice, then you have seen one definition of practice.”

Figure.

The extent of agreement among clinical faculty respondents with the following statements: “The expectations for what my practice entails are clear to me” (n = 78) and “The policies for my promotion are clear to me” (n = 78), United States, 2019. Based on responses to a survey of faculty at Council on Education for Public Health–certified schools of public health who had the word “clinical” in their title (n = 81).

Another respondent’s comments may indicate that at their institution teaching is conflated with, or seen as a component of, practice. In response to the question “How is practice of a clinical track faculty defined at your unit?” the respondent wrote, “Teaching is the primary responsibility, plus service. There are no research obligations; only that which is related to teaching.”

Clarity of Promotion Policies

Twenty-nine of 78 (37.2%) respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the promotion policies for clinical faculty were clear (Figure). Compared with respondents who had a lower academic rank, respondents with a higher academic rank said that their promotion policies were clearer than the policies for those with a lower academic rank; 8 of 9 full professors, 13 of 24 associate professors, and 8 of 45 assistant professors agreed or strongly agreed that promotion policies were clear (χ2[10] = 29.65; P = .001). Similarly, the longer respondents had been on the clinical track at their institution, the greater the perception that promotion policies were clear. Of 77 respondents (those who provided a response to their time on the clinical track and to their agreement about clarity of promotion policies), 12 of 20 faculty on the track for ≥11 years, 4 of 10 faculty on the track for 7-10 years, 4 of 12 faculty on the track for 4-6 years, and 8 of 35 faculty on the track for 0-3 years agreed or strongly agreed that promotion policies were clear (χ2[15] = 33.50; P = .004). The clarity of promotion policies did not differ by whether the respondent held a doctoral degree, had soft money or hard salary, or had a higher or lower teaching load.

Discussion

Our results offer important insights into characteristics of the clinical faculty workforce. Our findings indicate that clinical faculty are highly educated and have diverse training. We found that clinical faculty tend to be at the assistant rank, their positions are not tenure eligible, and their initial contract lengths are brief. Work expectations for clinical faculty commonly include research, teaching, service, and student advising/mentoring. Practice—an expectation for about one-third of respondents—was often poorly defined and understood. Clinical faculty reported a similar lack of clarity about promotion policies. These conditions may pose recruitment challenges for institutions that wish to create or sustain clinical faculty tracks.

Our sample was similar to the population of clinical faculty from which they were drawn, 9 in the proportion of assistant professors (57% vs 53%, respectively), associate professors (31% vs 31%, respectively), and full professors (12% vs 16%, respectively). More than half of respondents to our survey reported being at the assistant level and few reported being full professors. Comparatively, the tenure-track distribution across ranks in schools of public health is considerably more balanced (32% assistant professors, 29% associate professors, 39% full professors). 12 This disparity could be related to the short-term contract lengths of clinical faculty or lack of clarity about promotion policies, especially among respondents at the assistant and associate ranks. Also, traditional systems of documenting faculty contributions (prioritizing research, noting teaching and service) may not include the contributions of clinical faculty. The disparity between rank distribution and lack of clarity in promotion policies has been reported across clinical faculty in other health profession fields. 13

Clinical faculty in our study reported shorter contract lengths compared with national data from non–tenure-track faculty across disciplines. 7 Nationally, 38% of full-time non–tenure-track faculty across disciplines at 4-year institutions have 1-year contracts, 7 whereas more than half of our respondents reported being hired on an annual or short-term contract. Furthermore, 96.3% of our sample reported that their appointment did not offer tenure. Longer contract lengths and intention to be tenured lead to high levels of engagement and a sense of belonging within a faculty member’s unit. 8 Conversely, contingent, short-term contracts without the option of tenure may convey an implicit message to clinical faculty that their work is of less value to the institution than the work of tenure-track faculty. 14

In addition, short-term contracts may inhibit meaningful scholarship because they do not allow time for applying to and conducting grant-funded research activities, developing relationships with collaborators, publishing scholarship (ie, books, conference abstracts, articles), and participating in other professional activities beyond teaching. This limited ability to conduct scholarship or practice-oriented projects and using conventional promotion criteria may limit advancement opportunities. Our results suggest that clinical faculty are not being promoted to higher ranks as quickly as tenure-track faculty are: 17% of assistant clinical professors remained at the assistant rank for ≥7 years and 68% of clinical faculty remained at the associate rank for ≥7 years. We speculate that the rank imbalance and longer times in rank are due in large part to short contract lengths. The reason for this imbalance should be studied.

In other health science fields, clinical faculty appointments have specialized tracks such as clinician, researcher, or educator to help define their practice roles and provide an organizational structure for their schools. 5,15,16 In our study, about one-quarter of respondents indicated no definition of practice at their institution or that they interpreted practice themselves. Notably, school or unit-specific definitions of practice, as conveyed in respondents’ open-ended responses, suggest that definitions of practice vary widely across schools of public health. Implications of unclear practice expectations for both clinical faculty and students in schools of public health should be investigated, given the outsized role clinical faculty likely play in connecting students to public health practice opportunities.

Our research team was surprised by the small percentage of respondents who reported practice as a work activity. In public health, one might expect that a clinical faculty member’s practice would be an integral part of their role, but only one-third of respondents reported engaging in practice activities. Hollenshead et al 17 reported that full-time, non–tenure-track positions are trending toward a portfolio more like the tenure track. These positions provide additional coverage for service duties to ease the time burden on faculty. 17 Future research should investigate how faculty across tracks conduct public health practice activities at schools of public health.

The US Government Accountability Office reports that “contingent [non–tenure-track] faculty teach close to half or more of all courses and credit hours” at 4-year public institutions. 13 This high teaching load is part of a longstanding nationwide trend of hiring proportionately fewer tenure-track faculty and more non–tenure-track faculty. 18,19 At our institution, a school of public health at a large Midwestern university, an expansion in the number of academic programs has led to increased clinical faculty. The realities of institutional budgets and trends in public health education enrollment could lead to a continuation of this trend. 20 More research is needed to understand the size, growth, and contributions of all non–tenure-track faculty tracks to the operations of US schools and programs of public health. Examining and articulating the contributions that clinical and other non–tenure-track faculty make to academic programs will help schools of public health to understand the value of these faculty.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Our inclusion criteria had some drawbacks. Although we focused on faculty whose primary appointment was clinical, our inclusion criteria did not limit participants to full-time employees. Therefore, the sample may include some part-time employees who could have different appointment terms and duties than full-time employees. In addition, we did not include programs of public health in our sample. Future research should include clinical faculty working in programs of public health to better understand how clinical faculty contribute to public health education.

Some study limitations related to the generalizability of our sample. Due to nonresponse bias, our results may not be generalizable to all clinical faculty at schools of public health. In addition, because our survey was anonymous, we were unable to comment on the representativeness of our sample compared with all US schools of public health.

We also had limitations in the completeness of our data. Although the population of 264 eligible clinical faculty from which we solicited responses was based on the most recently available information, 9 some information may have been outdated or incorrect. The eligible faculty could have left the school, changed roles, or had a title such as “practice” but hired with the same intent as the clinical faculty we identified. Thus, our sample was narrower than the population of all clinical faculty. We did not collect data on demographic characteristics, so we were unable to describe the demographic composition of our sample. The survey also lacked items that would have provided additional information about our sample, including the content area in which respondents worked, current contracts (as opposed to initial contracts), nonrenewal of contracts, and policies that define termination of employment. Other lines of inquiry, such as the role of clinical faculty in mentoring doctoral students and additional information about administrative roles, should be explored.

Although nearly all (96%) participants reported service duties, only 34% of participants reported having practice expectations. It is possible that respondents conflated service and practice when reporting their duties. If this was the case, it would further highlight our finding that about one-third of clinical faculty are not clear on what clinical practice entails.

Finally, our research team consisted of clinical faculty at a single school of public health. Our experiences, perspectives, and interests shaped the survey and interpretations and may have introduced bias.

Despite these limitations, our sample represents an important step in understanding the roles, expectations, activities, and promotion process for clinical faculty in public health. Future research should document the range of faculty track options and investigate the roles, expectations, activities, promotion process, and working conditions of each. Identifying demographic characteristics should be a priority in future studies.

Conclusions

The clinical track is part of a growing presence of non–tenure-track faculty in schools of public health. Our exploratory work highlights important trends in expectations for scholarly activities, teaching, and practice among clinical faculty. The track expands possibilities for schools of public health to broaden and strengthen partnerships across the fields, because clinical faculty are poised to address emergent public health challenges and pandemic response efforts and lead advocacy activities related to racism as a public health issue. 21,22 This work is fundamental to advancing our nation’s health but is poorly captured by traditional research performance metrics. Our findings highlight potential challenges associated with the clinical track, including the variability in appointment terms and expectations across US schools of public health. These findings should motivate dialogue within and across schools of public health to clearly define the track. Failing to standardize and clarify expectations for practice and promotion may limit the attractiveness and utility of the track. Our research demonstrates that clinical faculty are vital members of academic public health institutions. Schools of public health should work with clinical faculty to improve employment terms, clarify expectations, and strategize how they may help fulfill institutions’ goals for research, teaching, mentoring, and practice efforts.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Angela Beck, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan School of Public Health, who participated in conceptualizing the investigation.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Ella August, PhD, MA, MS https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036

Olivia S. Anderson, Dr.PhD, MPH, RD https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8313-3682

References

- 1. Welch WH., Rose W. Institute of Hygiene: being a report submitted by Dr. William H Welch and Wickliffe Rose to the General Education Board, Rockefeller Foundation. May 27, 1915. RG 1.1, Series 200L. Sleepy Hollow, NY: Rockefeller Foundation Archives; 1916.

- 2. Sullivan LM., Galea S. The evolution of public health teaching. In: Sullivan LM., Galea S., eds. Teaching Public Health. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2019:3-14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Commission on Excellence in Educational Administration; Griffiths DE, Stout RT, Forsyth PB, eds. Leaders for America’s Schools: The Report of the National Commission on Excellence in Educational Administration. University Council for Educational Administration; 1988.

- 4. Council on Education for Public Health . Accreditation criteria: schools of public health and public health programs. 2016. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://ceph.org/assets/2016.Criteria.pdf

- 5. Jones RF., Gold JS. The present and future of appointment, tenure, and compensation policies for medical school clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):993-1004. 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smesny AL., Williams JS., Brazeau GA., Weber RJ., Matthews HW., Das SK. Barriers to scholarship in dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5): 10.5688/aj710591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Association of University Professors . Data snapshot: contingent faculty in US higher ed. 2018. Accessed October 2, 2020. https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/10112018%20Data%20Snapshot%20Tenure.pdf

- 8. US Government Accountability Office . Contingent workforce: size, characteristics, compensation, and work experiences of adjunct and other non–tenure-track faculty. 2017. Accessed October 2, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-49

- 9. Anderson OS., Youatt E., Power L., August E. Clinical-track faculty: making them count in public health education. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):30-32. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teddlie CB., Tashakkori AM. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bryman A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done? Qual Res. 2006;6(1):97-113. 10.1177/1468794106058877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health . 2019 Annual report. 2019. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.aspph.org/2019-annual-report

- 13. Chung KC., Song JW., Kim HM. et al. Predictors of job satisfaction among academic faculty members: do instructional and clinical staff differ? Med Educ. 2010;44(10):985-995. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03766.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reevy GM., Deason G. Stress, and anxiety among non–tenure track faculty. Front Psychol. 2014;5: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gehrke S., Kezar A. Unbundling the faculty role in higher education: utilizing historical, theoretical, and empirical frameworks to inform future research. In: Paulsen MB., ed. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Springer, Cham; 2015:93-150. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blush RR III., Mason HL., Timmerman NM. Pursuing the clinical track faculty role: from clinical expert to educator. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2017;28(3):243-249. 10.4037/aacnacc2017250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hollenshead C., Waltman J., August L., Miller J., Smith G., Bell A. Making the Best of Both Worlds: Findings From a National Institution-Level Survey on Non–Tenure-Track Faculty. Center for the Education of Women, University of Michigan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Association of University Professors . Tenure and teaching-intensive appointments: reports & publications. Updated 2014. Accessed October 2, 2020. https://www.aaup.org/report/tenure-and-teaching-intensive-appointments

- 19. Kezar A. Changing faculty workforce models. 2013. Accessed October 2, 2020. https://www.tiaainstitute.org/publication/changing-faculty-workforce-models

- 20. Resnick B., Leider JP., Riegelman R. The landscape of US undergraduate public health education. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(5):619-628. 10.1177/0033354918784911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Q&A with Angela Beck: contact tracing: use volunteers or paid public health corps? Michigan News. May 14, 2020. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://sph.umich.edu/news/2020posts/contact-tracing-use-volunteers-or-paid-public-health-corps.html

- 22. Op-ed: policing is a public health issue . The Michigan Daily. September 14, 2020. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.michigandaily.com/columns/op-ed-policing-public-health-issue