Abstract

Objectives

The adverse effects that racial and ethnic minority groups experience before, during, and after disaster events are of public health concern. The objective of this study was to examine disparities in the epidemiologic and geographic patterns of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality by race and ethnicity.

Methods

We used mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from January 1, 1999, through December 31, 2018. We defined natural disaster and extreme weather mortality based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes X30-X39. We calculated age-adjusted mortality rates by race, ethnicity, and hazard type, and we calculated age-adjusted mortality rate ratios by race, ethnicity, and state. We used geographic mapping to examine age-adjusted mortality rate ratios by race, ethnicity, and state.

Results

Natural disasters and extreme weather caused 27 335 deaths in the United States during 1999-2018. Although non-Hispanic White people represented 68% of total natural disaster and extreme weather mortality, the mortality rate per 100 000 population among non-Hispanic Black people was 1.87 times higher (0.71) and among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native people was 7.34 times higher (2.79) than among non-Hispanic White people (0.38). For all racial and ethnic groups, exposure to extreme heat and cold were the 2 greatest causes of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality. Racial and ethnic disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality were highest in the South, Southwest, Mountain West, and Upper Midwest.

Conclusions

Racial and ethnic minority populations have a greater likelihood of mortality from natural disaster or extreme weather events than non-Hispanic White people. Our study strengthens the current knowledge base on these disparities and may inform and improve disaster preparedness and response efforts.

Keywords: natural disasters, extreme weather, mortality, race, ethnicity, disparities, United States

The United States is one of the most disaster-prone countries with respect to the frequency, economic costs, and nature of hazard events. 1 Although natural disasters and extreme weather events affect all people, certain populations in the United States are affected more adversely than other populations based on factors such as age, sex, and socioeconomic status. 2 -8 In addition, people in racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and extreme weather events. 2 -5,9,10 Most factors related to such negative effects are systemic societal issues that prevent some populations from having equal access to preparedness and response resources. Disparities in language, socioeconomic status, structural racism, residential built environment, disaster preparedness resources, and resources available for disaster response contribute to the vulnerability of racial and ethnic minority groups to detrimental effects of natural disasters and extreme weather. 3,5,9 -12 Furthermore, vulnerability to such events has especially increased in the South and West of the United States, with race and ethnicity driving increases in disaster vulnerability. 13

Research on disasters and hazards has documented inequities in how racial and ethnic minority groups are exposed to and affected by natural disasters and extreme weather, 9 such as with Hurricane Katrina. 14 Compared with other racial and ethnic populations, Black people in parts of the United States have elevated exposure to wildfires 15,16 and encounter negative health effects in the aftermath of heat waves and hurricanes. 4,17,18 Hispanic/Latino communities in the United States are especially vulnerable to wildfires and experience adverse outcomes after hurricanes and extreme heat wave events. 15,17 -19 Disaster researchers have reported adverse health effects among Asian people in parts of the United States in the aftermath of various hazardous events, such as earthquakes and hurricanes. 20 -24 Indigenous populations in the United States have increased vulnerability to wildfires 15 and high susceptibility to poor health outcomes because of environmental disasters, such as oil spills. 25 -27

Although research emphasizes hazard exposures and the morbidity of disaster events, few studies have examined the mortality of natural disasters and extreme weather among racial and ethnic minority communities. The few studies that have examined racial and ethnic disparities in mortality caused by natural disasters and extreme weather have found elevated death rates caused by extreme heat, 28 -31 extreme cold, 31 -34 severe hurricane weather, 9,35 -38 and other natural disaster events 9,39 among people in racial and ethnic minority groups. Furthermore, studying the disproportionate rates of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among racial and ethnic minority populations is not only essential to addressing such disparities, but investigating the geographic patterns of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among racial and ethnic minority groups can show differences in vulnerability to such phenomena by features of place and space. Investigating such disparities may also inform tailored disaster preparedness and response interventions to lessen mortality among racial and ethnic minority communities resulting from natural disasters and extreme weather. Geographic methods have seldom been used to study the distribution of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality; however, areas in the South are most prone to disasters, 40 and racial and ethnic minority groups compose approximately one-third of the population in the South. 41,42

Most studies exploring natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among racial and ethnic minority groups have focused on a single disaster type or hazard event, preventing a comprehensive understanding of how natural disasters and extreme weather affect these populations. Also, research on natural disaster and extreme weather mortality has evaluated differences by race and ethnicity but has not considered geographic differences. 31 Moreover, research on the geographic distribution of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality has not analyzed differences in the distribution of such mortality by racial and ethnic minority populations. 40 The objectives of our study were to (1) analyze mortality from natural disasters and extreme weather by race and ethnicity, (2) assess differences in mortality from specific hazard types within racial and ethnic groups, and (3) examine geographic patterns of mortality from natural disasters and extreme weather by race and ethnicity.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality by race and ethnicity. We used secondary data that were aggregated, de-identified, and publicly accessible through a government database maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As such, this research did not meet the definition of human subjects research, nor was the study subjected to review by an institutional review board.

We obtained mortality data for all 50 states and the District of Columbia from the Underlying Cause of Death Detailed Mortality File of the CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database for January 1, 1999, through December 31, 2018. 43 We obtained data on mortality totals, population totals, age-adjusted mortality rates (per 100 000 population), race, and ethnicity for deaths with an underlying cause of death attributed to a natural disaster or extreme weather hazard. We stratified race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN).

We defined natural disaster and extreme weather mortality as deaths caused by exposure to forces of nature using the following International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) 44 codes: exposure to excessive natural heat (X30); exposure to excessive natural cold (X31); exposure to sunlight (X32); victim of lightning (X33); victim of earthquake (X34); victim of volcanic eruption (X35); victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36); victim of cataclysmic storm (X37); victim of flood (X38); and exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39).

We calculated age-adjusted mortality rates from aggregated counts of natural disaster and extreme weather deaths by race, ethnicity, and type of natural hazard. We calculated age-adjusted mortality rate ratios (RRs) to identify disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality by race and ethnicity. We standardized all age-adjusted measures to the 2000 US standard population. We mapped state-level natural disaster and extreme weather age-adjusted mortality RRs to visualize geographic disparities in mortality by race and ethnicity for the contiguous United States. Data on natural disaster and extreme weather mortality by state represent the place of residence of the decedent. Because of privacy concerns, we suppressed mortality counts and rates if they were based on <10 deaths. Mortality rates were statistically unreliable if they were based on <20 deaths. We conducted all analyses using RStudio version 1.2.5042 (RStudio, Inc) and mapping using ArcMap version 10.7 (Esri, Inc).

Results

During 1999-2018, a total of 27 335 deaths in the United States were due to natural disasters and extreme weather (Table 1). Compared with non-Hispanic White people, the mortality rate per 100 000 population was 7.34 times higher among non-Hispanic AI/AN people (2.79) and 1.87 times higher among non-Hispanic Black people (0.71), yet lower among Hispanic people (0.30) and non-Hispanic Asian people (0.11).

Table 1.

Age-adjusted natural disaster and extreme weather mortality rates by race and ethnicity, United States, 1999-2018 a

| Disaster type (ICD-10 code) b | No. of deaths c | Age-adjusted mortality rate per 100 000 population (95% CI)c | Age-adjusted mortality rate ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | |||

| All hazard types | 18 466 | 0.38 (0.38-0.39) | Reference |

| Exposure to excessive natural heat (X30) | 4890 | 0.10 (0.09-0.10) | |

| Exposure to excessive natural cold (X31) | 9641 | 0.19 (0.19-0.20) | |

| Exposure to sunlight (X32) | 14 | Unreliable | |

| Victim of lightning (X33) | 546 | 0 | |

| Victim of earthquake (X34) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of volcanic eruption (X35) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36) | 599 | 0 | |

| Victim of cataclysmic storm (X37) | 2046 | 0.04 (0.04-0.04) | |

| Victim of flood (X38) | 350 | 0 | |

| Exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39) | 371 | 0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | |||

| All hazard types | 4714 | 0.71 (0.69-0.73) | 1.87 |

| Exposure to excessive natural heat (X30) | 1574 | 0.24 (0.22-0.25) | |

| Exposure to excessive natural cold (X31) | 2348 | 0.37 (0.36-0.39) | |

| Exposure to sunlight (X32) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of lightning (X33) | 49 | 0 | |

| Victim of earthquake (X34) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of volcanic eruption (X35) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of cataclysmic storm (X37) | 632 | 0.07 (0.06-0.07) | |

| Victim of flood (X38) | 47 | 0 | |

| Exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39) | 55 | 0.01 (0-0.01) | |

| Hispanic | |||

| All hazard types | 2226 | 0.30 (0.29-0.31) | 0.79 |

| Exposure to excessive natural heat (X30) | 1115 | 0.15 (0.14-0.16) | |

| Exposure to excessive natural cold (X31) | 682 | 0.11 (0.10-0.12) | |

| Exposure to sunlight (X32) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of lightning (X33) | 134 | 0 | |

| Victim of earthquake (X34) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of volcanic eruption (X35) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36) | 19 | Unreliable | |

| Victim of cataclysmic storm (X37) | 124 | 0.01 (0-0.01) | |

| Victim of flood (X38) | 63 | 0 | |

| Exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39) | 86 | 0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | |||

| All hazard types | 309 | 0.11 (0.10-0.12) | 0.29 |

| Exposure to excessive natural heat (X30) | 127 | 0.03 (0.03-0.04) | |

| Exposure to excessive natural cold (X31) | 125 | 0.04 (0.03-0.04) | |

| Exposure to sunlight (X32) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of lightning (X33) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of earthquake (X34) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of volcanic eruption (X35) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of cataclysmic storm (X37) | 23 | 0 | |

| Victim of flood (X38) | 12 | Unreliable | |

| Exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39) | 10 | Unreliable | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | |||

| All hazard types | 1252 | 2.79 (2.62-2.95) | 7.34 |

| Exposure to excessive natural heat (X30) | 178 | 0.41 (0.35-0.48) | |

| Exposure to excessive natural cold (X31) | 987 | 2.20 (2.06-2.35) | |

| Exposure to sunlight (X32) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of lightning (X33) | 17 | Unreliable | |

| Victim of earthquake (X34) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of volcanic eruption (X35) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of avalanche, landslide, and other earth movements (X36) | <10 | Suppressed | |

| Victim of cataclysmic storm (X37) | 17 | Unreliable | |

| Victim of flood (X38) | 11 | Unreliable | |

| Exposure to other and unspecified forces of nature (X39) | 36 | 0.09 (0.06-0.12) | |

| Totald | 27 335 | 0.40 (0.40-0.41) | |

Abbreviation: ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision.

aData source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 43

bData source: World Health Organization. 44

cMortality counts and rates are suppressed if based on <10 deaths. Mortality rates are statistically unreliable if based on <20 deaths.

dTotal death count due to natural disasters and extreme weather includes 368 people with unspecified race and/or ethnicity.

Overall, mortality associated with extreme temperatures (excessive heat or cold exposures) represented most of the deaths caused by natural disaster and extreme weather across racial and ethnic groups, ranging from 79% of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among non-Hispanic White people to 93% of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among non-Hispanic AI/AN people. Mortality attributed to excessive cold exposures composed 52%, 50%, 31%, 40%, and 79% of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic AI/AN people, respectively. Mortality due to excessive heat exposures composed 26%, 33%, 50%, 41%, and 14% of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic AI/AN people, respectively.

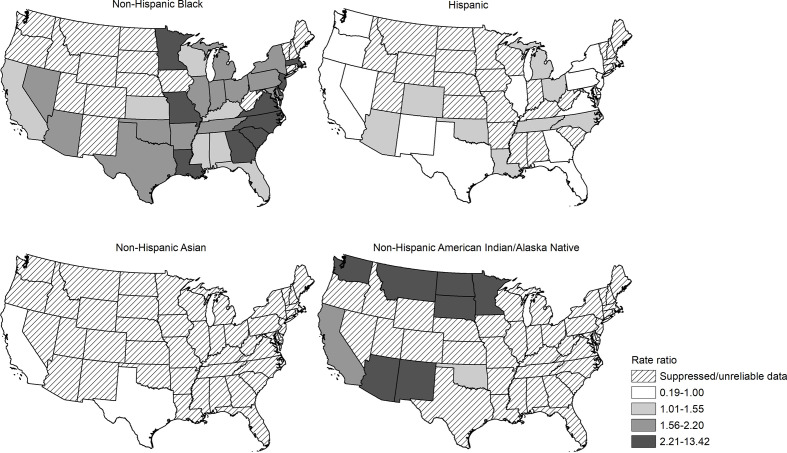

Overall, mortality caused by natural disasters and other natural hazards was concentrated largely among racial and ethnic minority groups residing in the South, Southwest, West, and Upper Midwest (Figure). The greatest disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality among non-Hispanic Black people occurred in the South: Delaware (RR = 3.59), Louisiana (RR = 2.86), Georgia (RR = 2.41), Virginia (RR = 2.35), South Carolina (RR = 2.28), North Carolina (RR = 2.25), and Maryland (RR = 2.06) (Table 2). Among Hispanic people, disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality were greatest in the South and Southwest: Louisiana (RR = 1.51), Tennessee (RR = 1.28), Oklahoma (RR = 1.22), Colorado (RR = 1.21), and Arizona (RR = 1.18). Non-Hispanic AI/AN people experienced large disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality in the Southwest (New Mexico RR = 13.42; Arizona RR = 9.26) and in the West and Upper Midwest (South Dakota RR = 13.29; Minnesota RR = 8.67; North Dakota RR = 6.37; Montana RR = 5.02). Most natural disaster and extreme weather deaths among non-Hispanic Asian people occurred in California and Texas, although at lower mortality rates than among non-Hispanic White people.

Figure.

Geographic distribution of age-adjusted natural disaster and extreme weather mortality rate ratios, by race, ethnicity, and state, contiguous United States, 1999-2018. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 43 The reference group for all rate ratios is non-Hispanic White.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted natural disaster and extreme weather mortality rate ratios, by race, ethnicity, and state, United States, 1999-2018 a

| State | Non-Hispanic Black b | Hispanic b | Non-Hispanic Asian b | Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All states | 1.87 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 7.34 |

| Alabama | 1.26 | —c | —c | —c |

| Alaska | —c | —c | —c | 6.87 |

| Arizona | 1.99 | 1.18 | —c | 9.26 |

| Arkansas | 1.85 | —c | —c | —c |

| California | 1.31 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 2.19 |

| Colorado | —c | 1.21 | —c | —c |

| Connecticut | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Delaware | 3.59 | —c | —c | —c |

| Florida | 1.53 | 0.94 | —c | —c |

| Georgia | 2.41 | 0.93 | —c | —c |

| Hawaii | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Idaho | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Illinois | 2.15 | 0.79 | —c | —c |

| Indiana | 1.90 | —c | —c | —c |

| Iowa | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Kansas | 1.53 | —c | —c | —c |

| Kentucky | 1.06 | —c | —c | —c |

| Louisiana | 2.86 | 1.51 | —c | —c |

| Maine | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Maryland | 2.06 | 0.91 | —c | —c |

| Massachusetts | 2.22 | —c | —c | —c |

| Michigan | 2.11 | 1.06 | —c | —c |

| Minnesota | 3.08 | —c | —c | 8.67 |

| Mississippi | 1.39 | —c | —c | —c |

| Missouri | 2.29 | —c | —c | —c |

| Montana | —c | —c | —c | 5.02 |

| Nebraska | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Nevada | 1.82 | 0.81 | —c | —c |

| New Hampshire | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| New Jersey | 2.21 | 0.83 | —c | —c |

| New Mexico | —c | 0.98 | —c | 13.42 |

| New York | 1.72 | 0.76 | —c | —c |

| North Carolina | 2.25 | 1.04 | —c | —c |

| North Dakota | —c | —c | —c | 6.37 |

| Ohio | 1.93 | 1.41 | —c | —c |

| Oklahoma | 1.78 | 1.22 | —c | 1.46 |

| Oregon | —c | 0.82 | —c | —c |

| Pennsylvania | 2.00 | 0.90 | —c | —c |

| Rhode Island | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| South Carolina | 2.28 | —c | —c | —c |

| South Dakota | —c | —c | —c | 13.29 |

| Tennessee | 1.64 | 1.28 | —c | —c |

| Texas | 1.64 | 0.87 | 0.38 | —c |

| Utah | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Vermont | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Virginia | 2.35 | 0.71 | —c | —c |

| Washington | —c | 0.60 | —c | 2.50 |

| West Virginia | —c | —c | —c | —c |

| Wisconsin | 1.55 | —c | —c | —c |

| Wyoming | —c | —c | —c | —c |

aData source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 43

bThe reference group is non-Hispanic White.

cRate ratios could not be calculated because underlying mortality counts and rates were suppressed or statistically unreliable.

Discussion

Our study found higher mortality rates from natural disasters and extreme weather events among certain racial and ethnic minority populations and distinct geographic patterns for these disparities. Although non-Hispanic White people composed most (68%) of the natural disaster and extreme weather mortality, racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly non-Hispanic AI/AN and non-Hispanic Black people, had higher mortality rates from natural disasters or extreme weather events. This finding is consistent with previous research, which found that racial and ethnic minority groups have higher mortality rates than non–racial and ethnic minority groups due to forces of nature. 9,28 -32,34,35 Although non-Hispanic AI/AN people and non-Hispanic Black people had higher mortality rates, non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic people had lower overall mortality rates from natural disasters and extreme weather than non-Hispanic White people, with state-specific mortality rates among Hispanic people varying widely across the United States. Regardless of race and ethnicity, exposure to extreme cold and heat were the greatest causes of natural disaster and extreme weather mortality, which parallels the findings of previous studies. 28 -34 Geographically, disparities in mortality caused by natural disasters and other natural hazards were highest among racial and ethnic minority populations in states in the Mountain West, Upper Midwest, Southwest, and South. This finding is consistent with previous research that found that people living in southern states and states in the intermountain western region of the United States are the most susceptible to natural hazards mortality. 40

Limitations

This study had at least 5 limitations. First, misclassification may have occurred in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality because of difficulty in identifying deaths caused by forces of nature, resulting in deaths being attributed to other causes. 45 -47 Data on deaths associated with natural disasters and extreme weather events but occurring months or years after such events may not be appropriately captured in mortality databases, thereby underestimating natural disaster and extreme weather mortality. Also, misclassification in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality may exist because of varying criteria for determining underlying cause of death across states. 45 -48 Second, race and ethnicity assigned to deceased people is often based on observation, underestimating mortality rates among racial and ethnic minority groups, especially AI/AN and Hispanic people. 49 Third, we used ICD-10 codes X30-X39 to define natural disaster and extreme weather mortality, which excluded mortality caused by wildfires (ICD-10 code X01). 44 Although we could have included deaths with an ICD-10 code of X01 in our analysis, not all of these deaths would strictly be caused by wildfires. Fourth, natural disaster and extreme weather mortality is a rare health outcome with statistically unreliable or suppressed data in several states, preventing geographic analysis at more local levels. Finally, we analyzed deaths due to natural disasters and extreme weather events that occurred during 1999-2018 cumulatively, preventing any temporal analyses of the mortality data by race and ethnicity.

Conclusions

Our study strengthens the current knowledge base on the disproportionate effects of natural disasters and extreme weather on racial and ethnic minority communities, identifying racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality, which can inform and improve disaster preparedness and response efforts for these populations. Racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly non-Hispanic AI/AN and non-Hispanic Black people, have a greater likelihood of mortality from natural disasters or extreme weather events than non-Hispanic White people. Mortality caused by natural disasters and other natural hazards was highest among racial and ethnic minority groups residing in the South, Southwest, Mountain West, and Upper Midwest. AI/AN and Black communities may benefit from tailored disaster preparedness and response efforts in anticipation of, during, and after natural disaster and extreme weather events. Efforts to provide long-term resources to strengthen community infrastructure for disaster preparedness and response in racial and ethnic minority communities will be critical to stem persistent racial and ethnic disparities in natural disaster and extreme weather mortality. In addition, our findings may inform state-level disaster preparedness and response interventions that are designed to address natural disaster and hazard threats, historic disparities, and underlying health conditions in racial and ethnic minority communities. Addressing this public health issue requires collaboration among state, regional, and local public health and emergency response professionals, community organizations, and racial and ethnic minority communities, emphasizing geographic, cultural, and resource differences for racial and ethnic minority populations.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

J. Danielle Sharpe, PhD,MS https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1898-6202

Amy F. Wolkin, DrPH, MSPH https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4307-7641

References

- 1. Guha-Sapir D., Hoyois P., Wallemacq P., Below R. Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2016: The Numbers and Trends. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cutter SL., Boruff BJ., Shirley WL. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc Sci Q. 2003;84(2):242-261. 10.1111/1540-6237.8402002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Logan JR., Issar S., Xu Z. Trapped in place? Segmented resilience to hurricanes in the Gulf Coast, 1970-2005. Demography. 2016;53(5):1511-1534. 10.1007/s13524-016-0496-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sastry N., Gregory J. The effect of Hurricane Katrina on the prevalence of health impairments and disability among adults in New Orleans: differences by age, race, and sex. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:121-129. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sastry N., Gregory J. The location of displaced New Orleans residents in the year after Hurricane Katrina. Demography. 2014;51(3):753-775. 10.1007/s13524-014-0284-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lowe SR., Sampson L., Gruebner O., Galea S. Community unemployment and disaster-related stressors shape risk for posttraumatic stress in the longer-term aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(5):440-447. 10.1002/jts.22126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nomura S., Parsons AJQ., Hirabayashi M., Kinoshita R., Liao Y., Hodgson S. Social determinants of mid- to long-term disaster impacts on health: a systematic review. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016;16(2):53-67. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.01.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sirey JA., Berman J., Halkett A. et al. Storm impact and depression among older adults living in Hurricane Sandy–affected areas. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017;11(1):97-109. 10.1017/dmp.2016.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fothergill A., Maestas EG., Darlington JD. Race, ethnicity and disasters in the United States: a review of the literature. Disasters. 1999;23(2):156-173. 10.1111/1467-7717.00111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burger J., Gochfeld M., Lacy C. Ethnic differences in risk: experiences, medical needs, and access to care after Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2019;82(2):128-141. 10.1080/15287394.2019.1568329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cox K., Kim B. Race and income disparities in disaster preparedness in old age. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61(7):719-734. 10.1080/01634372.2018.1489929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donner WR., Lavariega-Montforti J. Ethnicity, income, and disaster preparedness in Deep South Texas, United States. Disasters. 2018;42(4):719-733. 10.1111/disa.12277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cutter SL., Finch C. Temporal and spatial changes in social vulnerability to natural hazards. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2301-2306. 10.1073/pnas.0710375105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cutter SL., Emrich CT., Mitchell JT. et al. The long road home: race, class, and recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Environment. 2006;48(2):8-20. 10.3200/ENVT.48.2.8-20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davies IP., Haugo RD., Robertson JC., Levin PS. The unequal vulnerability of communities of color to wildfire. PLoS One. 2018;13(11): 10.1371/journal.pone.0205825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu JC., Wilson A., Mickley LJ. et al. Who among the elderly is most vulnerable to exposure to and health risks of fine particulate matter from wildfire smoke? Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(6):730-735. 10.1093/aje/kwx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davidson TM., Price M., McCauley JL., Ruggiero KJ. Disaster impact across cultural groups: comparison of Whites, African Americans, and Latinos. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;52(1-2):97-105. 10.1007/s10464-013-9579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knowlton K., Rotkin-Ellman M., King G. et al. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(1):61-67. 10.1289/ehp.11594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burger J., Gochfeld M., Pittfield T., Jeitner C. Responses of a vulnerable Hispanic population in New Jersey to Hurricane Sandy: access to care, medical needs, concerns, and ecological ratings. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2017;80(6):315-325. 10.1080/15287394.2017.1297275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kulkarni M., Pole N. Psychiatric distress among Asian and European American survivors of the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(8):597-604. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181813290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kung WW., Liu X., Goldmann E. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the short and medium term following the World Trade Center attack among Asian Americans. J Community Psychol. 2018;46(8):1075-1091. 10.1002/jcop.22092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kung WW., Liu X., Huang D., Kim P., Wang X., Yang LH. Factors related to the probable PTSD after the 9/11 World Trade Center attack among Asian Americans. J Urban Health. 2018;95(2):255-266. 10.1007/s11524-017-0223-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vu L., Vanlandingham MJ. Physical and mental health consequences of Katrina on Vietnamese immigrants in New Orleans: a pre- and post-disaster assessment. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(3):386-394. 10.1007/s10903-011-9504-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vlahov D., Galea S., Ahern J. et al. Alcohol drinking problems among New York City residents after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(9):1295-1311. 10.1080/10826080600754900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palinkas LA., Petterson JS., Russell J., Downs MA. Community patterns of psychiatric disorders after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1517-1523. 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palinkas LA., Petterson JS., Russell JC., Downs MA. Ethnic differences in symptoms of post-traumatic stress after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19(1):102-112. 10.1017/S1049023X00001552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palinkas LA., Russell J., Downs MA., Petterson JS. Ethnic differences in stress, coping, and depressive symptoms after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(5):287-295. 10.1097/00005053-199205000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rackers DC., Donnell H. Heat-related illnesses and deaths—Missouri, 1998, and United States, 1979-1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(22):469-473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sathyavagiswaran L., Fielding JE., Dassy D. Heat-related deaths—Los Angeles County, California, 1999-2000, and United States, 1979-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(29):623-626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCormick S., Madrigano J., Zinsmeister E. Preparing for extreme heat events: practices in identifying mortality. Health Secur. 2016;14(2):55-63. 10.1089/hs.2015.0048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thacker MTF., Lee R., Sabogal RI., Henderson A. Overview of deaths associated with natural events, United States, 1979-2004. Disasters. 2008;32(2):303-315. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zumwalt R., Broudy D. Hypothermia-related deaths—New Mexico, October 1993–March 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(50):933-935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Propst MT., Middaugh JP. Hypothermia-related deaths—Alaska, October 1998–April 1999, and trends in the United States, 1979-1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(1):11-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ion-Nedelcu N., Craciun D., Molnar G. Hypothermia-related deaths—Virginia, November 1996–April 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(49):1157-1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brunkard J., Namulanda G., Ratard R. Hurricane Katrina deaths, Louisiana, 2005. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(4):215-223. 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818aaf55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kishore N., Marqués D., Mahmud A. et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):162-170. 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santos-Burgoa C., Sandberg J., Suárez E. et al. Differential and persistent risk of excess mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico: a time-series analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(11):e478-e488. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30209-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santos-Lozada AR., Howard JT. Use of death counts from vital statistics to calculate excess deaths in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria. JAMA. 2018;320(14):1491-1493. 10.1001/jama.2018.10929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zahran S., Peek L., Brody SD. Youth mortality by forces of nature. Child Youth Environ. 2008;18(1):371-388. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Borden KA., Cutter SL. Spatial patterns of natural hazards mortality in the United States. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. US Census Bureau . 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. 2017. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2017/5-year.html

- 42. Kaiser Family Foundation . Population distribution by race/ethnicity. 2017. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-raceethnicity

- 43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC WONDER online database: about underlying cause of death, 1999-2018. Accessed May 14, 2020. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- 44. World Health Organization . ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luber GE., Sanchez CA., Conklin LM. Heat-related deaths—United States, 1999-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(29):796-798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wetli CV., Smith P. Hypothermia-related deaths—Suffolk County, New York, January 1999–March 2000, and United States, 1979-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(4):53-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Donoghue ER., Graham MA., Jentzen JM., Lifschultz BD., Luke JL., Mirchandani HG. Criteria for the diagnosis of heat-related deaths: National Association of Medical Examiners. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1997;18(1):11-14. 10.1097/00000433-199703000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taylor EV., Vaidyanathan A., Flanders WD., Murphy M., Spencer M., Noe RS. Differences in heat-related mortality by citizenship status: United States, 2005-2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S2):S131-S136. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sandefur GD., Campbell ME., Eggerling-Boeck J. Racial and ethnic identification, official classifications, and health disparities. In: Anderson NB., Bulatao RA., Cohen B., eds. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. National Academies Press; 2004:25-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]