Summary

A cluster is a special matter level above a single atom and between macroscopic and microscopic matter, and it is an important bridge to understanding the relationship between the structure and function of matter. Here, we perform a comprehensive theoretical study of 2D planar Aun (n = 1–12) clusters doped with both magnesium and germanium. Two interesting results are found, namely the rapid 3D "roll-up" structural growth of the GeMgAun (n = 1–12) cluster ground state isomers, and the relative "alienation" of the different sizes of the Aun (n = 1–12) cluster framework towards the Ge atom, and the relative "affinity" towards the Mg atom. This study will not only enrich the data on gold-based clusters but will also provide a simple and clear theoretical guide for the 3D structuring of planar clusters, i.e. the doping of different classes of "affinition" and "alienatation" atoms.

Subject areas: Density functional theory, molecular clusters

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The global minima of MgGeAun (n = 3–12) clusters are searched using the CALYPSO program

-

•

Mg and Ge doping of Aun (n = 2–12) clusters results in rapid structural 3D "roll-up"

-

•

MgGeAun (n = 3–12) clusters exhibit relative affinity for Mg and alienation to Ge atoms

-

•

MgGeAu4 cluster is the most stable one than others

Density functional theory; molecular clusters.

Introduction

As one of the well-known "stars" in the field of cluster science, gold nanoclusters have been eagerly sought after by academics for the past 20 years (Jin, 2010; Jin et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2012). This is owing in part to nanoclusters' enormous practical potential. Because the size of gold nanoclusters is typically comparable to the electron Fermi wavelength, the density of states that are continuously distributed in the macroscopic state is discrete in the cluster state, resulting in gold nanoclusters having a wide range of optical (Jin, 2015), catalytic (Liu and Corma, 2018), chiral (Pelayo et al., 2018), bio-detection and bio-imaging (Shang et al., 2011), and other properties. The properties of gold nanoclusters are derived from their size-dependent structures, although it is not easy to determine them experimentally (Gruene et al., 2008; Jin, 2010, 2015; Jin et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2003; Shang et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2018). Fortunately, predicting the structures of gold nanoclusters theoretically is not so difficult, especially for computational searches of gas-phase Aun clusters at the quantum-chemical level based on density functional theory (DFT). Taking small-size gold nanoclusters as an example, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2002) and Häkkinen et al. (Häkkinen and Landman, 2000) used DFT to investigate gold clusters, and they found that the ground state structure of gold nanoclusters can remain planar at Au6 and Au7 size, respectively. Then, Zhao et al. (Zhao et al., 2003) and Serapian et al. (Serapian et al., 2013), Hansen et al. (Hansen et al., 2013) and Olson et al. (Olson et al., 2005) also used DFT and demonstrated that the ground state of the Au8 cluster is also planar in structure. In addition, Götz et al. (Götz et al., 2013) employed DFT to study gold clusters and found that Au10 cluster possesses the 2D structure, while Johansson et al. (Johansson et al., 2014) used the revTPSS functional and the random phase approximation to predict the neutral gold clusters to become 3D at a size of 11 gold atoms. Idrobo et al. (Idrobo et al., 2007) and Deka et al. (Deka and Deka, 2008) theoretically confirmed that up to the Au13 cluster ground-state structure is planar by DFT. Li et al. (Xiao and Wang, 2004) further found that the structures of the 15 Au atomic clusters are all planar in the ground state. The conclusion that small-sized gold nanoclusters (Au3-12) have kinds of planar structures is also supported by many other reports, like Ramiro (Ramos et al., 1987) and Arratia-Perez et al.(Arratia-Perez et al., 1989), Zhao et al. (Zhao et al., 2012a), Shao et al. (Shao et al., 2012), and Sui et al. (Sui et al., 2014), and also confirmed by Goldsmith et al. (Goldsmith et al., 2019). It is necessary to explain why, for the same theoretical prediction of small-sized nanoclusters, the conclusions obtained by different researchers at different times. This is because DFT methods rely on the choice of functionals and basis sets, which are still being developed now. Unfortunately, for theoretical chemists, there is no one-size-fits-all functional and basis set that can be applied to all atoms.

At least for now, based on the above studies, we are confident enough to believe that the ground state of the nanoclusters in the Au3-12-sized clusters is most likely to be planar. Therefore, one interesting research scientific issue is whether the size-dependent property of the structure of small-sized gold-based alloy nanoclusters changes the planar structure of gold nanoclusters. In other words, doping gold-based nanoclusters can be thought of as changing the 2D gold nanocluster structure, and there will always be a critical size from 2D to 3D transition, or a kind of 3D “roll-up” effect. It is shown that different doping atom types and different atomic numbers have different effects on the planar structure of small-sized gold clusters. Our previous work on bromine-atom-doped gold clusters confirmed that, for the ground state clusters, the transition from 2D to 3D structures starts with Au5Br (Zhu et al., 2021), while other studies have shown that Au10Re (Sui et al., 2014), Au8Be (Chen et al., 2011), Au4La (Zhao et al., 2010), Au3Bi (Zhang et al., 2019), Au3C (Yan et al., 2013), Au9Mn (Zhang et al., 2012), Au8V (Nhat and Nguyen, 2011), Au11Sc (Ge et al., 2010), Au3Ti, Au5Ti and Au7Ti (Toprek and Koteski, 2016) are the critical sizes for such 3D "roll-up." The study of doped gold clusters with two same atoms has also been studied, for example, Ca2Aun, Be2Aun, Cu2Aun, Ag2Aun, Si2Aun, P2Aun, Na2Aun, Mg2Aun. and Al2Aun showing that the ground state structures from Ca2Au3 (Zhao et al., 2012a), Be2Au5 (Zhao et al., 2012b), Cu2Au6 and Ag2Au6 (Zhao et al., 2011), Si2Au2, P2Au3, (Li et al., 2012), Na2Au2, Mg2Au4 and Al2Au2 (Li et al., 2013) are no longer planar. Moreover, the effect of such two same kinds of atom doping on the planar structure is sometimes discontinuous, i.e., Be2Au5, Cu2Au6, and Ag2Au6 are 3D structures, but Be2Au6, Cu2Au7, Ag2Au7 revert to planar geometry. So, it is interesting to gain insight into whether different types of two atoms will break this 3D "roll-up" discontinuity, and, what will be the relative affinity and distancing differences of gold nanoclusters for different atoms after doping.

Based on the above motivation, in this work, we will theoretically investigate the 3D "roll-up" of small-size Aun nanoclusters doped with both Ge and Mg atoms. At the same time, whether gold nanoclusters exhibit relatively different affinities and distances for Mg and Ge atoms will be also investigated together. In principle, any two different atom-doped gold nanoclusters are worth studying, but Mg and Ge were chosen for this work because they are both common materials in alloy materials. Specifically, the geometry, relative stability, electronic structure, bonding properties, and spectroscopic properties of MgAunGe (n = 1–12) nanoclusters will be systematically investigated.

Results and discussions

The structures of MgGeAun clusters

The three lowest energy isomers structures of MgGeAun-(i) (i = 1–3; n = 1–12) clusters are presented in Figures 1 and 2, as well as the symmetry, electron state, and the energy difference from the ground state (in eV). For all MgGeAun-(1) represents the ground state isomer, while MgGeAun-(2) is the isomer with the 2nd lowest energy. As the ground state isomers are very important (their properties will be discussed specifically in the following section), we also put their relevant calculations in Table 1, where we also present the range of the calculated vibrational frequencies. As can be seen in Table 1, the lowest vibrational frequencies of all the ground state isomers are positive, so they meet the requirement that the imaginary frequencies cannot exist in introduction. For cluster, structure-dependent size growth, isomer MgGeAu1-(1) (Cs, 2A'') shows a triangular structure where the distances of Mg-Ge, Ge-Au. and Mg-Au are 2.63 Å, 2.65 Å, and 2.72 Å, respectively. Isomers MgGeAu1-(2) (C2v, 2Σg) and MgGeAu1-(3) (C2v, 4Σg) are 0.69 eV and 1.37 eV higher than the energy of the ground state isomer, respectively, and both have a linear structure, where the Mg atoms are in the middle. The ground state isomer MgGeAu2-(1) (Cs, 1A') possesses an irregular tetrahedral structure, while the isomers MgGeAu2-(2) (C2v, 1A1) and MgGeAu2-(3) (C2v, 1A1) exhibit triangular and tetragonal planar structures. The energies of MgGeAu2-(2) and MgGeAu2-(3) show 0.42 eV and 0.93 eV higher than that of MgGeAu2-(1). It is easy to find that when the isomer MgGeAu2-(1) is used as the core and an Au atom is captured in different directions, the isomers MgGeAu3-(1) (Cs, 2A') and MgGeAu3-(2) (Cs, 2A') can be formed, both of which exhibit tetrahedral and the hexahedral geometry composed of double tetrahedra geometries. Isomer MgGeAu3-(3) (C1, 2A) displays a 2D planar structure and can be formed through isomer MgGeAu2-(3) by attracting an Au atom. In addition, the second- and third-lowest energy isomers of the MgGeAu3 cluster are 0.90 eV and 1.80 eV higher than the energy of their ground state isomer. For MgGeAu4, the structure of its ground state isomer, MgGeAu4-(1) (C1, 1A), is based on the structure of the isomer MgGeAu3-(2) by attracting an Au atom on the outer side of the Mg atom. The isomers MgGeAu4-(2) (Cs, 1A') and MgGeAu4-(3) (C1, 1A), which have energies 1.71 eV and 1.74 eV higher than the ground state, exhibit a kind of tetrahedral-based deformation structure. For the MgGeAu5 cluster, the energy of its ground state isomer is 0.43 eV and 0.71 eV lower than that of the second- and third-lowest energy isomers, respectively. In addition, the isomers MgGeAu5-(1) (C1, 2A) and MgGeAu5-(2) (C1, 2A) are constructed by attracting an Au atom in different directions with the isomer MgGeAu4-(1) as their "core." The isomer MgGeAu5-(3) (C1, 2A), on the other hand, shows a 3D mesh-like structure. The structures of the ground state and the second-lowest energy isomer of the MgGeAu6 cluster are also easily obtained by the deformation of the isomeric MgGeAu5-(1) by the adsorption of an Au atom. The third lowest energy isomer of the MgGeAu6 cluster is then an expanded 3D mesh-like with one more Au atom of the isomer MgGeAu5-(3) structure. Furthermore, isomers MgGeAu6-(2) (Cs, 1A') and MgGeAu6-(2) (Cs, 1A') have energies 0.13 eV and 0.31 eV higher than isomer MgGeAu6-(1) (C1, 1A).

Figure 1.

The three lowest energy isomers structures of MgGeAun-(i) (i = 1–3; n = 1–6) clusters, and the energy difference (eV) to the lowest energy isomer

Figure 2.

The three lowest energy isomers structures of MgGeAun-(i) (i = 1–3; n = 7–12) clusters, and the energy difference (eV) to the lowest energy isomer

Table 1.

Symmetry, electronic state, average bonding energy (Eb), the second order difference energy (Δ2E), fragmentation energy (Ef), HOMO-LUMO energy gap (Egap) for α- electrons, and vibrational frequency in the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters

| Cluster | Symmetry | State | Eb (eV) | Δ2E (eV) | Ef (eV) | Egap-α (eV) | Highest Freq. (ω−1) | Lowest Freq. (ω−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgGeAu1 | Cs | 2A" | 2.13 | – | – | 1.68 | 264 | 140 |

| MgGeAu2 | C1 | 1A | 2.64 | 4.14 | 0.55 | 1.78 | 280 | 47 |

| MgGeAu3 | Cs | 2Aʹ | 2.82 | 3.58 | −0.5 | 3.11 | 381 | 30 |

| MgGeAu4 | C1 | 1A | 3.03 | 4.08 | 1.35 | 3.32 | 371 | 24 |

| MgGeAu5 | C1 | 2A | 2.99 | 2.74 | −0.92 | 2.57 | 333 | 17 |

| MgGeAu6 | C1 | 1A | 3.07 | 3.65 | 1.22 | 2.58 | 331 | 15 |

| MgGeAu7 | C1 | 2A | 3.00 | 2.43 | −1.01 | 1.10 | 294 | 16 |

| MgGeAu8 | C1 | 1A | 3.05 | 3.44 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 313 | 10 |

| MgGeAu9 | C1 | 2A | 3.05 | 3.03 | −0.47 | 1.33 | 288 | 12 |

| MgGeAu10 | C1 | 1A | 3.08 | 3.50 | 0.57 | 0.97 | 270 | 8 |

| MgGeAu11 | C1 | 2A | 3.07 | 2.94 | −0.93 | 1.74 | 291 | 9 |

| MgGeAu12 | C1 | 1A | 3.13 | – | – | 2.04 | 301 | 14 |

As displayed in Figure 2, for the ground state isomers MgGeAun-(1) (n = 7–12), their structures are based on the deformation of smaller size clusters by attracting an Au atom in different orientations, while the "core" is the geometry of the isomer MgGeAu3-(2). In other words, this double-tetrahedral structure with Mg and Ge atoms at two vertices plays the role of the "seed" for the growth of the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 4–12) clusters. As for the isomers MgGeAun-(2) and MgGeAun-(3) (n = 7–12), their structures show some diversity and are not entirely grown from the "seed" of MgGeAu3-(2). The structures of these isomers have larger size 3D mesh-like structures, such as MgGeAu8-(2) and MgGeAu8-(3), and another complex 3D structure in which the Mg and Ge atoms are far apart, such as the isomers MgGeAu9-(2), MgGeAu10-(2), MgGeAu10-(3), MgGeAu11-(2) and MgGeAu11-(3). Except for the isomers MgGeAu8-(3) (Cs, 1A'), MgGeAu10-(3) (Cs, 1A'), MgGeAu11-(2) (Cs, 2A') and MgGeAu11-(3) (Cs, 2A'), all other isomers MgGeAun-(i) (i = 1–3; n = 7–12) exhibit C1 symmetry and their corresponding 1A and 2A electronic states. As shown in Figure 2, the energy differences of the isomers MgGeAun-(i) (i = 2–3; n = 7–12) with respect to their respective ground states are 0.55eV, 0.63eV, 0.46eV, 0.59eV, 0.11eV, 0.77eV, 0.26eV, 0.39eV, 0.31eV, 0.58eV, 0.20eV and 0.33eV.

The above analysis leads to the following important conclusion: the structure of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) nanoclusters will fast "roll up" into a 3D structure. For the ground state clusters, all the ground state nanoclusters are 3D except for MgGeAu1 which must be planar. In addition, a double tetrahedral geometry as the "core" or "seed" for the growth of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) nanocluster structure has been found and confirmed by our study. In order to better discuss below-the-ground state nanoclusters, which are relatively more stable and more likely to be experimentally synthesized because of their relatively lowest energy, atomic coordinate information is provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. In addition, in order to make the structures of these isomers more readily available to the reader, their MOL format files are named Data S1 in the Supplementary Materials, relating to the MgGeAun-(i) isomers, respectively.

The relative stabilities

The relative stability of clusters is an important study in cluster research because it is size-dependent. By studying the relative stability of clusters, we can find the local most stable clusters, which is an important tool to define the "magic" clusters. The "magic" clusters can be thought of as sizes with a high probability of occurrence when atoms are aggregated into clusters under experimental conditions. Here, the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) nanoclusters will be investigated by the following four energies, which are binding energy per atom (Eb), second-order energy difference (Δ2E), fragmentation energy (Ef), and LUMO-HOMO energy gap (Egap), as displayed in the following Equations 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

| (Equation 3) |

| (Equation 4) |

In Equations 1, 2, and 3, the energy corresponding to the atom or cluster is denoted by E. In Equation 4, Egap is the energy difference between the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO). The calculated results are presented in Table 1 and the curves with cluster size are plotted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relative stability parameters for α-electrons in the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters

(A) Eb, (B) Δ2E, (C) Ef, (D) Egap.

As displayed in Table 1 and Figure 3A, the Eb values of the MgGeAu1-4 clusters are rapidly increasing, while the Eb curve of the MgGeAu4-12 clusters is oscillating and increasing in smaller magnitudes. Overall, the clusters are more stable with the increase in the number of Au atoms and the interatomic bonding. Specifically, the largest Eb value, 3.07 eV, occurs at MgGeAu6, followed by the MgGeAu4 cluster with the second-largest Eb value of 3.03 eV, indicating that they both have the strongest local stability. Δ2E is a typical local stability parameter that characterizes the energy relations of Xn cluster with respect to Xn-1 and Xn+1 (Xn means an arbitrary cluster and n is the size). Figure 3B shows that Δ2E curve of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) nanoclusters has a distinct odd-even oscillatory trend, and even-size clusters have higher stability than odd-size ones. Specifically, the first and second strongest peaks of the Δ2E curve occur at MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6 with 4.08 eV and 3.65 eV, respectively, indicating that they are much more stable than their neighbors. The fragmentation energy Ef is the energy required to split the MgGeAun cluster into the MgGeAun-1 cluster and an Au atom, so the larger the value of Ef, the more stable its corresponding cluster is. As Figure 3C displayed, the Ef curve of the MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters is like the Δ2E curve and exhibits odd-even oscillatory behavior. The Ef of the even-size clusters is significantly larger than that of the odd-size ones, MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6 possess the largest and second-largest Ef values, 1.35 eV and 1.22 eV, respectively, indicating that both are more stable than the other clusters. Interestingly, this odd-even oscillation stability pattern of doped gold clusters has been confirmed in all similar works, even in the pure gold clusters studies (Assadollahzadeh and Schwerdtfeger, 2009; Bonačić-Koutecký et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2011; Fernández et al., 2006; Häberlen et al., 1997; Häkkinen and Landman, 2000; Wang et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2003, 2010; 2012a; 2012b; 2011; Zhu et al., 2021). This phenomenon is mainly derived from the difference in the stability of open-shell and closed-shell structures. Egap can be used to characterize the chemical stability of the clusters, and a higher Egap value means less susceptibility to chemical reactions. Quantum mechanics tells us that there are only two possible spin quantum numbers for a single electron, so in quantum chemical calculations, we usually distinguish between two different spin quantum numbers of electrons as α-electrons (spin up) and β-electrons (spin down). For any closed-shell system, because each α-electron has a β-electron paired with it (determined by the Pauli exclusion principle), there is no need to distinguish between them. Although for the open-shell system, when the system itself carries an odd number of electrons, there must be an unpaired α-electron, so the behavior of α- and β-electrons needs to be discussed separately. As the odd-sized MgGeAun (n is an odd number) clusters are open-shell systems, which have unequal α and β electrons, Table 1 and Figure 3D show the Egap of α electrons, while the Egap curve of β electrons is plotted in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials. For both α- and β-electrons, MgGeAu4 has the largest Egap value and thus possesses the highest chemical stability, while the cluster of MgGeAu6 has the third and second largest values and thus possesses considerable high chemical stability.

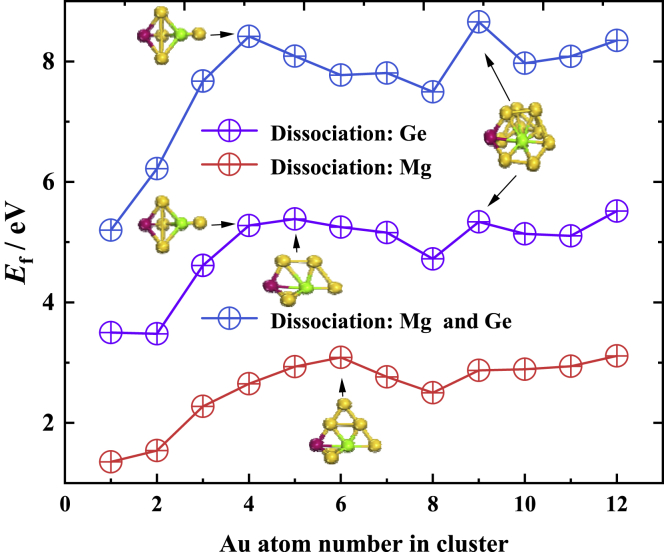

Furthermore, Equation 3 studies only one channel of dissociation of the GeMgAun cluster, i.e., the dissociation of GeMgAun into GeMgAun-1 and an Au. It is necessary to further investigate other possible dissociation channels corresponding to the dissociation energy. Equations 5, 6, and 7 show three other possible dissociation channels for the GeMgAun cluster

| (Equation 5) |

| (Equation 6) |

| (Equation 7) |

After structural optimization and frequency calculations of MgAun, GeAun, and Aun (n = 2–13) clusters at the same computational level, the dissociation energy results for these different channels are presented in Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials and plotted in Figure 4. As the calculated results show, the GeMgAun cluster has the largest dissociation energy for the simultaneous dissociation of Ge and Mg, and the lowest dissociation energy for the dissociation of Mg alone. Compared to the dissociation Au atoms in Figure 3C, the dissociation energies of the three different channels in Figure 4 do not show significant odd-even oscillations with cluster size, but the MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu9 clusters are relatively stable than others for the Ge and Mg simultaneous dissociation channels. For the Ge dissociation channel, MgGeAu5 and MgGeAu9 have the local maximum dissociation energy, while the dissociation energies of MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6 are extremely close to that of MgGeAu5, indicating that these four clusters are relatively stable. For the Mg atom dissociation channel, the dissociation energy of MgGeAu6 has a local maximum, implying that it has the strongest relative stability. Obviously, different dissociation channels yield different local most stable clusters, but regardless of the channels, the three MgGeAu4, MgGeAu6, and MgGeAu9 always possess very high stability.

Figure 4.

Dissociation energies for Mg, Ge, and both Mg and Ge three channels from the lowest-energy states MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters

In summary, the above study can be concluded that the ground state of MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6 clusters have robust stability, and thus are candidates for the "magic" clusters.

Charge transfer property

The charge transfer properties and electronic configuration of the cluster can be analyzed by NCP and NEC in NBO calculations, which can help us to understand the mechanism of cluster formation. The NCP and NEC calculations for each atom of the ground state MgGeAun (n = 1–12) cluster are shown in Tables 2, S4, and S5 in the Supplementary Materials, and their size dependence is plotted in Figure 5. The results show the following facts, (i). All Mg atoms lose electrons and play the role of electron donors in all clusters, (ii). All Ge atoms, on the other hand, are electron acceptors and thus positively charged, (iii). There are 78 Au atoms in total, while 70 of them are electron gainers and negatively charged, and the remaining 8 are electron losers and positively charged. In Figure 5A, the different atoms are colored red and blue, respectively, after charge transfer, and it can be clearly seen that there is a distinct red atom in each cluster, which corresponds to the Mg atom. Numerically, all Mg atoms lose electrons in the range from 0.73e to 1.52e, while all Ge atoms gain electrons in the range of [-0.46e, −0.01e], a few Au atoms are positively charged even though they are distributed in a small range of [0.01e, 0.15e], and most Au atoms are negatively charged from −0.43e to −0.01e. The charge transfer property of the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 2–12) clusters originates from the fact that Mg (1.2), Ge (1.8), Au (2.4) have different electronegativities. The electronegativity values of both Mg and Ge are smaller than that of Au, so Au is more likely to get electrons from Mg and Ge atoms when all three of them are aggregated and as the number of Au atoms increases.

Table 2.

Natural Charge Population and Natural Electron Configuration on Mg and Ge atoms in the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters

| Cluster | Natural Charge Population on Mg (in |e|) | Natural Charge Population on Ge (in |e|) | Natural Electron Configuration on Mg (in |e|) | Natural Electron Configuration on Mg (in |e|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgGeAu1 | 0.73 | −0.39 | [core]3S1.183p0.06 | [core]4S1.914p2.41 |

| MgGeAu2 | 0.90 | −0.38 | [core]3S1.043p0.05 | [core]4S1.844p2.50 |

| MgGeAu3 | 1.15 | −0.21 | [core]3S0.753p0.09 | [core]4S1.864p2.31 |

| MgGeAu4 | 1.15 | −0.20 | [core]3S0.763p0.09 | [core]4S1.814p2.34 |

| MgGeAu5 | 1.26 | −0.19 | [core]3S0.743p0.09 | [core]4S1.804p2.35 |

| MgGeAu6 | 1.28 | −0.24 | [core]3S0.633p0.08 | [core]4S1.784p2.42 |

| MgGeAu7 | 1.39 | −0.46 | [core]3S0.513p0.09 | [core]4S1.694p2.73 |

| MgGeAu8 | 1.38 | −0.15 | [core]3S0.533p0.08 | [core]4S1.754p2.37 |

| MgGeAu9 | 1.46 | −0.18 | [core]3S0.453p0.07 | [core]4S1.714p2.44 |

| MgGeAu10 | 1.44 | −0.15 | [core]3S0.473p0.08 | [core]4S1.704p2.42 |

| MgGeAu11 | 1.52 | −0.01 | [core]3S0.413p0.06 | [core]4S1.744p2.25 |

| MgGeAu12 | 1.44 | −0.08 | [core]3S0.483p0.07 | [core]4S1.694p2.36 |

Figure 5.

Natural charge population (NCP) and natural electron configuration (NEC) on Mg and Ge atoms for the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 2–12) clusters

(A). NCP on Mg and Ge, (B) NEC on Mg, (C) NEC on Ge, and (D) NEC on Au.

Figures 5B–5D show the NEC distributions of Mg, Ge, and Au atoms, respectively, with the horizontal, dashed lines showing the valence electron configurations of the corresponding bare atoms. It can be found that the valence 3s orbital of the Mg atom always loses electrons while the 3p orbital gains electrons, similarly, the 4s orbital of the Ge atom loses electrons while the 4p orbital gains electrons. This indicates that Mg is 3s3p orbitals hybridized in the cluster, while Ge is 4s4p orbitals hybridized. For the Au atoms, their 5d orbitals lose electrons, while the 6p orbitals are all gaining electrons, and the complexity comes from the 6s orbitals of Au, which are mostly gaining electrons, but a few are also losing them. Thus, the Au atoms in the cluster are 5d6s6p orbitals hybridized.

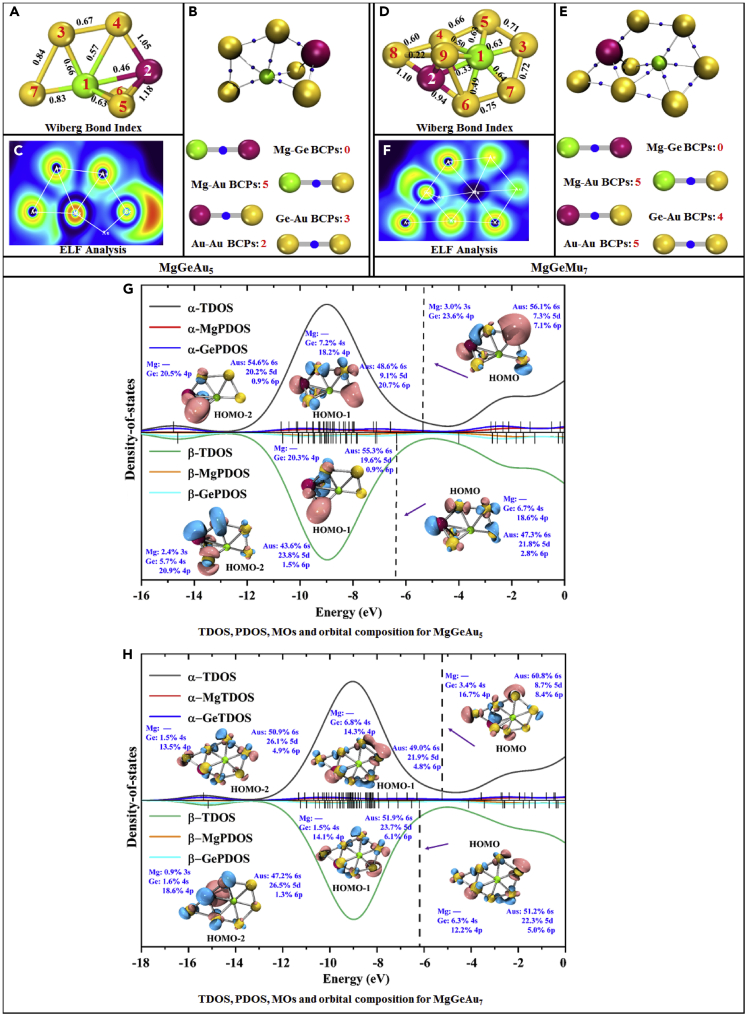

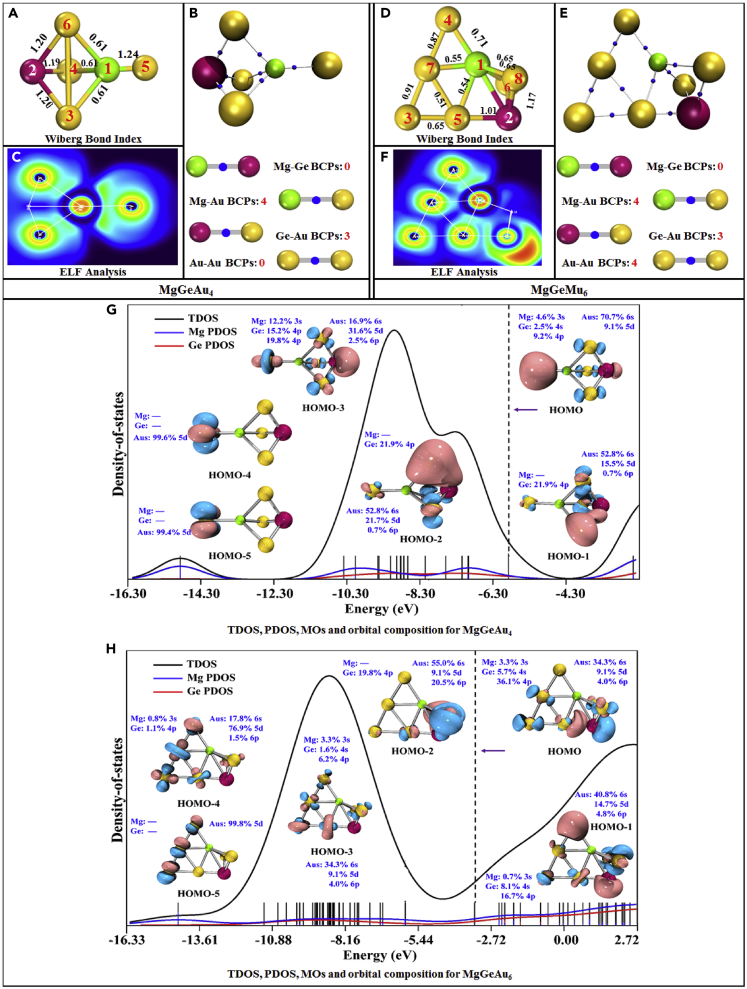

The topology analysis of the chemical bond property of MgGeAun clusters

During cluster formation, the following scientific questions are often raised. Is a chemical bond formed between two atoms in a cluster? what type of bond is it? Is there a cluster size-dependent property of chemical bond strength? In the atom-in-molecule (AIM) theory, the interatomic bond critical point (BCP) calculation and found were proposed to solve the above problems. This is because if a BCP is searched between two atoms, it indicates that they are bonded, and then the nature of the bond can be determined through the Laplacian function of electron density (▿2ρ) and ELF values at this point. Specifically, ▿2ρ(BCP) < 0 and ELF(BCP) > 0.5 mean a covalent bond, while ▿2ρ(BCP) > 0 and ELF(BCP) < 0.5 suggests a non-covalent bond. Such calculations for the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters were conducted and they are shown in Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials, and even more, the interatomic Wiberg bond index and their distances were also investigated for a more comprehensive study of the chemical bond properties. In addition, the total density of states (TDOS), the partial density of states (PDOS of Mg and Ge atoms), molecular orbitals (MOs), and the three highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2) were also studied in order to further investigate the chemical bond in the clusters. These results are plotted in Figures 6, 7, and S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 6.

Wiberg bond index (WBI), BCPs, ELF, MOs, composition, TDOS, and PDOS for α-electrons and β-electrons of the most unstable MgGeAu5 and MgGeAu7 clusters

(A and D). WBI, (B and E). BCPs, (C and F). ELF, (G and H). MOs, composition, TDOS, and PDOS.

Figure 7.

Wiberg bond index (WBI), BCPs, ELF, MOs, composition, TDOS, and PDOS for α-electrons and β-electrons of the most stable MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6 clusters

(A and D). WBI, (B and E). BCPs, (C and F). ELF, (G and H). MOs, composition, TDOS, and PDOS.

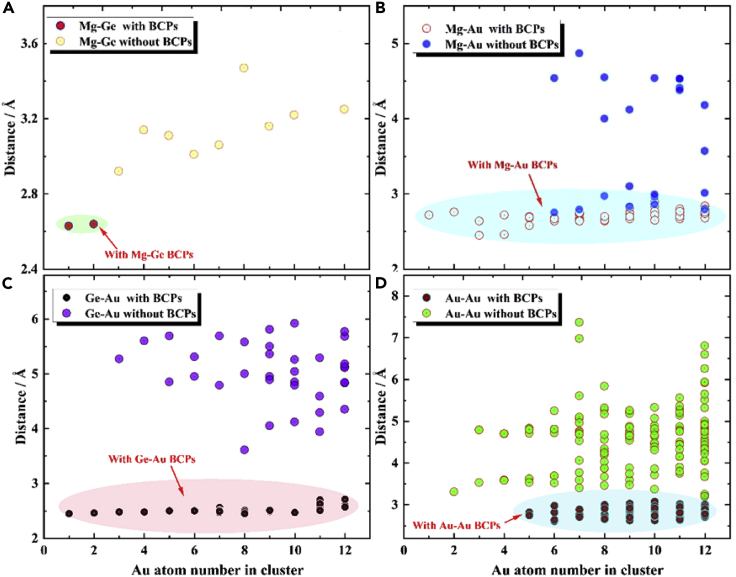

For the study of the number of atomic bonds, Figure S2 in the Supplementary Material counts the search of BCP for each cluster, and it can be easily found that Mg-Ge bonds exist only in MgGeAu1 and MgGeAu2, while Au-Au bonds start to appear in clusters larger than the size of MgGeAu4 (i.e., starting from MgGeAu5), and the number of Mg-Au bond is always excess to Ge-Au, in addition, Au -Au BCPs increase in proportion to the cluster size. Interestingly, Mg atoms can bond with up to 8 surrounding Au atoms, while Ge atoms can only form bonds with up to 4 Au atoms. Figure 8 analyzes the relationship between interatomic distances and the presence of BCPs, as shown in Figures 8A, 8C, and 8D, which show that the distances of Mg-Ge, Ge-Au, and Au-Au can determine the presence of BCPs between them, i.e., there is a clear boundary between the region with and without BCPs. In contrast, Figure 8B shows that the distance and bonding relationship of Mg-Au is more complex, and the intuitive perception that chemical bonds are formed at closer distances does not apply here. However, when we fit the Wiberg bond index against the interatomic distance, as shown in Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials, the closer the atoms are to each other for the same type of chemical bond, the stronger the Wiberg bond index will be. In addition, combining the geometries in Figures 1 and 2, one interesting conclusion is that Mg atoms tend to "immerse" inside the Aun (n = 1–12) clusters, while Ge atoms tend to be "crowded" to the edges! This means that small-sized Aun (n = 1–12) clusters exhibit relative affinity for Mg atom and alienation from Ge atom. It is known from the charge transfer study in charge transfer property that Mg atoms tend to lose electrons while Au tends to gain electrons, so they can easily form ionic bonds, but both Ge and Au tend to gain electrons and it is relatively difficult for them to form bonds.

Figure 8.

The atom distance (in Å) between two atoms for each ground state of MgGeAun (n = 2–12) clusters, with atom1-atom2 BCPs means that in this distance, BCPs were found between these two atoms in such distances, while those distributions that were not circled meant that BCPs were not found at these distances

(A) Mg-Ge, (B) Mg-Au, (C) Ge-Au, (D) Au-Au atoms.

Figures 6 and 7 show the results for the two relatively locally most unstable and two most stable clusters, MgGeAu5,7 and MgGeAu4,6, in terms of bond type (through ELF), the density of states, molecular orbitals, and orbital composition. Similar results for the other clusters, MgGeAu1-3, and MgGeAu 8-12, are presented separately in Figures S4–S11 and Table S7 of the Supplementary Materials. Obviously, ▿2ρ > 0 and ELF <0.5 hold in all BCPs, suggesting that Mg-Ge, Mg-Au, Ge-Au, and Au-Au bonds are all non-covalent bonds. The total density of states plots and partial density of states curves, such as those displayed in Figures 6G, 6H, 7G, and 7H, show that the contributions of both Mg and Ge atoms are relatively small in each molecular orbital (except for MgGeAu1). For example, for the locally most unstable open-shell cluster, MgGeAu7, its α- and β-electrons HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2 orbitals contain no Mg atomic orbital contributions (except for the β-electron HOMO-2 orbital which has 0.9% Mg atomic 3s orbital contributions), while there come some Ge atomic 4s (greater than 10%) and 4p (less than 10%) orbital contributions, and about 50% of the contributions are from the 6s orbitals of Au atoms, as well as a small amount of 5d and 6p orbital contributions. A similar situation occurs for the most locally stable closed-shell cluster, MgGeAu4, where 70.7% and 9.1% of the HOMO orbitals come from the 6s and 5d orbitals of the Au atoms, while the Mg atom contributes 4.6% of the 3s orbital, while 2.5% and 9.2% of the contributions come from the 4s and 4p orbitals of the Ge atom. Therefore, we can quantify the electronic configuration of the clusters revealed by the NEC conclusion in charge transfer property in terms of orbital composition. First, although the Mg atom is 3s3p orbital hybridized, its contribution to the MOs is extremely small and can be neglected in many cases. Second, the contribution of the 4s4p orbital hybridization of the Ge atom to the MOs cannot be neglected, but it mainly comes from its 4p orbitals. Finally, the dominant contribution of the 6s5d6p orbital hybridization of the Au atom to the MOs is the 6s orbital.

Conclusions

In summary, this work investigates the structure, stability, charge transfer, and bonding properties of small-sized Aun (n up to12) clusters possessing 2D planar structures when they are doped with Mg and Ge atoms. Interestingly, the geometries of the MgGeAun (n = 2–12) clusters rapidly "roll up" into 3D structures. The "seed" of cluster growth is a double-tetrahedral structure with Mg and Ge at the two vertices and three Au atoms forming a triangular base, on which almost all MgGeAun (n = 3–12) clusters were found to grow. Stability calculations for the ground state isomers reveal that even-size MgGeAun (n = 1–12) clusters are more stable than odd-size ones, with the two most stable clusters being MgGeAu4 and MgGeAu6. Charge transfers and electron configuration studies indicate that electrons are transferred from Mg atoms to Ge and most Au atoms, and Mg and Ge atoms are 3s3p orbitals and 4s4p orbitals hybridized, while Au is 5d6s6p orbitals hybridized. ELF and ▿2ρ calculations of BCPs based on AIM theory show that, as shown in Figure 9, Mg-Ge bonds exist only in MgGeAu1 and MgGeAu2, while Au-Au bonds start to appear in clusters larger than the size of MgGeAu4, and Mg-Ge, Mg-Au, Ge-Au, and Au-Au bonds are all non-covalent bonds. Interestingly, Mg atoms tend to "immerse" inside the Aun (n = 3–12) clusters, while Ge atoms tend to be "crowded" to the edges, suggesting that small-sized Aun (n = 3–12) clusters exhibit relative affinity for Mg atom and alienation from Ge atom. Finally, the studies on the density of states and orbital composition confirm that the 3s of Mg, 4p of Ge, and 6s of Au atom orbitals are the main contributors to clusters MOs.

Figure 9.

The appearance of Mg-Ge, Mg-Au, Ge-Au, and Au-Au bonds in the ground state of MgGeAun (n = 2–12) clusters

Limitations of the study

The present work is a standard theoretical study on Au-based clusters, although the structures of numerous isomers are predicted, the corresponding energies, electronic properties, and spectral properties are calculated, as well as some interesting phenomena in the formation of ground state isomers of various sizes are found. It must be acknowledged, however, that the absolute values of these calculations are dependent on the functional and basis set of the DFT. In addition, as the spectra calculated in this work are only for the ground states isomers, they are always not directly usable in spectroscopic experiments at specific temperatures and require the consideration of the weighted population of the Boltzmann distribution of several low-energy isomers at this temperature.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| CALYPSO | Wang et al., 2012 | http://www.calypso.cn |

| SPAP | Lv et al., 2012 | http://www.calypso.cn |

| Gaussian09 | Frish et al., 2016 | https://gaussian.com |

| Multiwfn | Lu and Chen, 2012 | http://sobereva.com/multiwfn/ |

| VMD | Humphrey et al., 1996 | http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Any further information and requests should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Ben-Chao Zhu (benchao_zhu@126.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new materials.

Experimental model and subject details

This work does not use any experimental models.

Method details

The initial guess structures of MgAunGe (n = 1–12) nanoclusters were constructed by CALYPSO software (Wang et al., 2010, 2012), which is based on the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm. CALYPSO structure prediction software has been successfully used for clusters (Lv et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021; 2019), crystals (Lu et al., 2020; Lu and Chen, 2020, 2021) and materials under high pressure (Chen et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020). For each size of MgAunGe nanocluster, 1000 structures will be generated (50 generations in total, 20 structures/generation), 80% of which will be generated by PSO, while the remaining 20% will be generated randomly. These generated structures will then be calculated in Gaussian 09 software (Frisch et al., 2016) for structural optimization with the low-level Hartree-Fock method. Not all the 1000 isomers obtained from the MgAunGe search of each size are useful, most of them can be removed by SPAP software (Wang et al., 2012) based on energy and structural similarity to select candidates for the next step of high-level structural optimization and frequency calculations with DFT in Gaussian09. The functional in the DFT calculation is chosen to be b3pw91 (Becke, 1992), the all-electron basis set 6-311g(d) (Krishnan et al., 1980) for Mg and Ge, and the pseudopotential basis set lanl2dz for Au atoms (Pritchard et al., 2019). In order to explain the rationality of this functional and basis set selection, we compared the theoretical calculation values of geometries (atomic distance in Å), vibration frequency (ω/cm−1), average binding energy (Eb in eV), vertical ionization potential (VIP) and vertical electron affinity (VEA) energy of Au2, Ge2 and Mg2 dimers at different level with the corresponding experimental data. Here we totally used five functionals, b3pw91, b3lyp, pbepbe, tpsstpss, wb97xd, and five base sets, lanl2dz, lanl2mb, sdd, 6-311g(d), 6-31g to test. The results are shown in the Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials, and one can find that Compared with the experimental data, b3pw91/lanl2dz and b3lyp/lanl2dz are reasonable choices for Au2 dimer (Barnett et al., 1999; K. Huber and Herzberg, 1979a; Perdew et al., 1992), but for Mg2 dimer, the average binding energy calculated by b3pw91/6-311g(d) is closer to the experimental value (K. P. Huber and Herzberg, 1979b; Ruette et al., 2005), and the error between the vibration frequency calculated by b3lyp/6-311g(d) and the experimental data is smaller. Finally, for Ge2 dimer, the calculated results of b3pw91/6-311g(d) are closer to the experimental data (Amadoruge and Weinert, 2008; Kingcade et al., 1986; Miller et al., 1986; Yoshida and Fuke, 1999) than b3lyp/6-311g(d) overall, except the VEA value. Therefore, we can confirm that the selection of b3pw91/lanl2dz for Au and b3pw91/6-311g(d) for Ge and Mg is reasonable. In addition, for each candidate isomer, the calculation also considered their different spin multiplicity, i.e., 1, 3, 5, 7 for the closed-shell layer and 2, 4, 6, 8 spin multiplicity for the open-shell layer. The goal of the frequency calculation is to ensure that the optimized isomers are not transition states, so if imaginary frequencies appear in the results, they need to be eliminated and reoptimized until all frequencies are positive.

Natural bond orbital (NBO) (Reed et al., 1988) was used to analyze the nature of charge distribution and orbital composition in clusters, including natural charge population (NCP), natural electron configuration (NEC), as well as natural atom orbital (NAO) composition. Wiberg bond index analysis (Wiberg, 1968) was performed to compare the Mg-Ge, Mg-Au, and Au-Au chemical bond in the ground state of MgAunGe (n = 1–12) nanoclusters. The study of chemical bonding between cluster atoms started with the search of bond critical points (BCPs) by Atom-in-Molecular (AIM) theory (Bader, 1985), and then the Laplacian function of electron density (▿2ρ (BCPs)) (Lu and Chen, 2013), electron localization function values (ELFs) (Becke and Edgecombe, 1990) of these BCPs was used to determine the nature of chemical bonds. AIM theory is a useful technique for the topological analysis of chemical bonding properties. Because in this theory, the architecture is composed of its electron-density standing points and the gradient paths of electron density starting and ending at these points. Thus, the atoms within any system and the chemical bonds between atoms are natural expressions of the observable electron density distribution function of the system. In addition, the molecular orbitals (MOs), the total density of states (TDOS) and partial density of states (PDOS) of Mg, Ge, and Au atoms were analyzed by Multiwfn software (Lu and Chen, 2012) for all the ground states of MgAunGe (n = 1–12) nanoclusters. The molecular orbital (MOs) diagram of each ground state isomer is drawn by VMD software (Humphrey et al., 1996).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The initial enthalpies of each size MgGeAun cluster isomer were counted and sorted by the cak.py package of the CALYPSO software. The structural simplification states were counted and removed according to the SPAP auxiliary program of the CALYPSO software.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Cultivating Project for Young Scholar at Hubei University of Medicine (No. 2020QDJZR015).

Author contributions

Ben-Chao Zhu: Software, Writing Original draft preparation, Methodology, Writing review & editing. Ping-Ji Deng: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. Jia Guo: Visualization, Investigation. Wen-Bin Kang: Formal analysis, Visualization. Lei Bao: Conceptualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Writing review & editing, Funding Acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: October 21, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105215.

Contributor Information

Ben-Chao Zhu, Email: benchao_zhu@126.com.

Lei Bao, Email: bolly@whu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Amadoruge M.L., Weinert C.S. Singly bonded catenated germanes: eighty years of progress. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:4253–4294. doi: 10.1021/cr800197r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arratia-Perez R., Ramos A.F., Malli G.L. Calculated electronic structure of Au13 clusters. Phys. Rev. B. 1989;39:3005–3009. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.39.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assadollahzadeh B., Schwerdtfeger P. A systematic search for minimum structures of small gold clusters Aun (n=2–20) and their electronic properties. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:064306. doi: 10.1063/1.3204488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader R.F.W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985;18:9–15. doi: 10.1021/ar00109a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett R.N., Cleveland C.L., Häkkinen H., Luedtke W.D., Yannouleas C., Landman U. Structures and spectra of gold nanoclusters and quantum dot molecules. Eur. Phys. J. D. 1999;9:95–104. doi: 10.1007/PL00010958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange-only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:2155–2160. doi: 10.1063/1.462066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A.D., Edgecombe K.E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:5397–5403. doi: 10.1063/1.458517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonačić-Koutecký V., Burda J., Mitrić R., Ge M., Zampella G., Fantucci P. Density functional study of structural and electronic properties of bimetallic silver–gold clusters: comparison with pure gold and silver clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:3120–3131. doi: 10.1063/1.1492800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Conway L.J., Sun W., Kuang X., Lu C., Hermann A. Phase stability and superconductivity of lead hydrides at high pressure. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;103:035131. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.103.035131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.-D., Kuang X.-Y., Zhao Y.-R., Shao P., Li Y.-F. Geometries, stabilities, and electronic properties of Be-doped gold clusters: a density functional theory study. Chinese Phys. B. 2011;20:063601. doi: 10.1088/1674-1056/20/6/063601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deka A., Deka R.C. Structural and electronic properties of stable Aun (n=2–13) clusters: a density functional study. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2008;870:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.theochem.2008.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández E.M., Soler J.M., Balbás L.C. Planar and cagelike structures of gold clusters: density-functional pseudopotential calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:235433. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.235433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., et al. 2016. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02. [Google Scholar]

- Ge G.x., Yan H.x., Jing Q. First-principle study of Aun Sc ( n = 2–13) clusters. Chi. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;23:416–424. doi: 10.1088/1674-0068/23/04/416-424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith B.R., Florian J., Liu J.-X., Gruene P., Lyon J.T., Rayner D.M., Fielicke A., Scheffler M., Ghiringhelli L.M. Two-to-three dimensional transition in neutral gold clusters: the crucial role of van der Waals interactions and temperature. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019;3:016002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.3.016002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Götz D.A., Schäfer R., Schwerdtfeger P. The performance of density functional and wavefunction-based methods for 2D and 3D structures of Au10. J. Comput. Chem. 2013;34:1975–1981. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruene P., Rayner D.M., Redlich B., van der Meer A.F.G., Lyon J.T., Meijer G., Fielicke A. Structures of neutral Au7, Au19, and Au20 clusters in the gas phase. Science. 2008;321:674–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1161166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häberlen O.D., Chung S.-C., Stener M., Rösch N. From clusters to bulk: a relativistic density functional investigation on a series of gold clusters Aun, n=6,…,147. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;106:5189–5201. doi: 10.1063/1.473518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Häkkinen H., Landman U. Gold clusters AuN (2<N<10) and their anions. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;62:R2287–R2290. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.62.R2287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.A., Piecuch P., Levine B.G. Communication: determining the lowest-energy isomer of Au8: 2D, or not 2D. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:091101. doi: 10.1063/1.4819693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K., Herzberg G. Vol. 4. 1979. Constants of Diatomic Molecules. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K.P., Herzberg G. Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure: IV. Constants of Diatomic Molecules. Springer US; 1979. Constants of diatomic molecules; pp. 8–689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrobo J.C., Walkosz W., Yip S.F., Öğüt S., Wang J., Jellinek J. Static polarizabilities and optical absorption spectra of gold clusters Aun, (n=2 –14 and 20) from first principles. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:205422. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.76.205422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R. Quantum sized, thiolate-protected gold nanoclusters. Nanoscale. 2010;2:343–362. doi: 10.1039/B9NR00160C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R. Atomically precise metal nanoclusters: stable sizes and optical properties. Nanoscale. 2015;7:1549–1565. doi: 10.1039/C4NR05794E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R., Zeng C., Zhou M., Chen Y. Atomically precise colloidal metal nanoclusters and nanoparticles: fundamentals and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:10346–10413. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M.P., Warnke I., Le A., Furche F. At what size do neutral gold clusters turn three-dimensional? J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:29370–29377. doi: 10.1021/jp505776d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X., Li Y., Zhu M., Jin R. Atomically precise alloy nanoclusters: syntheses, structures, and properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:6443–6514. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00633H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingcade J.E., Nagarathna-Naik H.M., Shim I., Gingerich K.A. Electronic structure and bonding of the molecule Ge2 from all-electron ab initio calculations and equilibrium measurements. J. Phys. Chem. 1986;90:2830–2834. doi: 10.1021/j100404a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R., Binkley J.S., Seeger R., Pople J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:650–654. doi: 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li X., Zhai H.-J., Wang L.-S. Au20: a tetrahedral cluster. Science. 2003;299:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1079879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Cao Y.P., Li Y.F., Shi S.P., Kuang X.Y. DFT study on size-dependent geometries, stabilities, and electronic properties of AunM2 (M = Si, P; n = 1–8) clusters. Eur. Phys. J. D. 2012;66:10. doi: 10.1140/epjd/e2011-20468-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-F., Li Y., Kuang X.-Y. Probing the structural and electronic properties of bimetallic Group-III metal-doped gold clusters: AunM2 (M = Na, Mg, Al; n = 1–8) Eur. Phys. J. D. 2013;67:132–139. doi: 10.1140/epjd/e2013-40039-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Corma A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4981–5079. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Chen C. Indentation-strain stiffening in tungsten nitrides: mechanisms and implications. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020;4:043402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.4.043402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Chen C. Indentation strengths of zirconium diboride: intrinsic versus extrinsic mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021;12:2848–2853. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Gong W., Li Q., Chen C. Elucidating stress-strain relations of ZrB12 from first-principles studies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:9165–9170. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Chen F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Chen F. Bond order analysis based on the laplacian of electron density in fuzzy overlap space. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2013;117:3100–3108. doi: 10.1021/jp4010345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Wang Y., Zhu L., Ma Y. Particle-swarm structure prediction on clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:084104. doi: 10.1063/1.4746757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T.M., Miller A.E.S., Lineberger W.C. Electron affinities of Ge and Sn. Phys. Rev. A Gen. Phys. 1986;33:3558–3559. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.33.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nhat P.V., Nguyen M.T. Trends in structural, electronic and energetic properties of bimetallic vanadium–gold clusters AunV with n = 1–14. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:16254–16264. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22078k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R.M., Varganov S., Gordon M.S., Metiu H., Chretien S., Piecuch P., Kowalski K., Kucharski S.A., Musial M. Where does the planar-to-nonplanar turnover occur in small gold clusters? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1049–1052. doi: 10.1021/ja040197l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelayo J.J., Valencia I., García A.P., Chang L., López M., Toffoli D., Stener M., Fortunelli A., Garzón I.L. Chirality in bare and ligand-protected metal nanoclusters. Adv. Phys. X. 2018;3:1509727. doi: 10.1080/23746149.2018.1509727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J.P., Chevary J.A., Vosko S.H., Jackson K.A., Pederson M.R., Singh D.J., Fiolhais C. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 1992;46:6671–6687. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.46.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard B.P., Altarawy D., Didier B., Gibson T.D., Windus T.L. New basis set exchange: an open, up-to-date resource for the molecular sciences community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019;59:4814–4820. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Zhu M., Wu Z., Jin R. Quantum sized gold nanoclusters with atomic precision. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:1470–1479. doi: 10.1021/ar200331z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A.F., Arratia-Perez R., Malli G.L. Dirac scattered-wave calculations on an icosahedral Au13 cluster. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 1987;35:3790–3798. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.35.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A.E., Curtiss L.A., Weinhold F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899–926. doi: 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruette F., Sánchez M., Añez R., Bermúdez A., Sierraalta A. Diatomic molecule data for parametric methods. I. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2005;729:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.theochem.2005.04.024. Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Theoretical Chemists of Latin Expression. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serapian S.A., Bearpark M.J., Bresme F. The shape of Au8: gold leaf or gold nugget? Nanoscale. 2013;5:6445–6457. doi: 10.1039/C3NR01500A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L., Dong S., Nienhaus G.U. Ultra-small fluorescent metal nanoclusters: synthesis and biological applications. Nano Today. 2011;6:401–418. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2011.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao P., Kuang X.-Y., Zhao Y.-R., Li Y.-F., Wang S.-J. Equilibrium geometries, stabilities, and electronic properties of the cationic AunBe+ (n =1-8) clusters: comparison with pure gold clusters. J. Mol. Model. 2012;18:3553–3562. doi: 10.1007/s00894-012-1365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J., Wang X., An P. Geometric evolution, stability trend and electronic properties of rhenium-doped gold clusters. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014;1028:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2013.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Kuang X., Keen H.D.J., Lu C., Hermann A. Second group of high-pressure high-temperature lanthanide polyhydride superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;102:144524. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.102.144524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toprek D., Koteski V. Ab initio calculations of the structure, energetics and stability of AunTi (n=1–32) clusters. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016;1081:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2016.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang G., Zhao J. Density-functional study of Aun (n=2–20) clusters: lowest-energy structures and electronic properties. Phys. Rev. B. 2002;66:035418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.66.035418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lv J., Zhu L., Ma Y. Crystal structure prediction via particle-swarm optimization. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:094116. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.094116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lv J., Zhu L., Ma Y. CALYPSO: a method for crystal structure prediction. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012;183:2063–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2012.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg K.B. Application of the pople-santry-segal CNDO method to the cyclopropylcarbinyl and cyclobutyl cation and to bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(68)88057-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Wang L. From planar to three-dimensional structural transition in gold clusters and the spin–orbit coupling effect. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;392:452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.05.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L.-L., Liu Y.-R., Huang T., Jiang S., Wen H., Gai Y.-B., Zhang W.-J., Huang W. Structure, stability, and electronic property of carbon-doped gold clusters AunC (n = 1–10): a density functional theory study. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:244312. doi: 10.1063/1.4852179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N., Xia N., Liao L., Zhu M., Jin F., Jin R., Wu Z. Unraveling the long-pursued Au144 structure by x-ray crystallography. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaat7259. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S., Fuke K. Photoionization studies of germanium and tin clusters in the energy region of 5.0–8.8 eV: ionization potentials for Gen (n=2–57) and Snn (n=2–41) J. Chem. Phys. 1999;111:3880–3890. doi: 10.1063/1.479691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Zhang H., Xin W., Chen P., Hu Y., Zhang X., Zhao Y. Probing the structural evolution and electronic properties of divalent metal Be2Mgn clusters from small to medium-size. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6052. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Zhang H., Zhao L., Li Y., Luo Y. Low-energy isomer identification, structural evolution, and magnetic properties in manganese-doped gold clusters MnAun (n=1–16) J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:1493–1502. doi: 10.1021/jp2094406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhang Y., Yang X.Q., Li G.Q., Lu Z.W. Probing the structures and electronic properties of anionic and neutral BiAun−1, 0 ( n= 2–20) clusters: a pyramid-like BiAu13 cluster. New J. Chem. 2019;43:10030–10037. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ01821B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yang J., Hou J.G. Theoretical study of small two-dimensional gold clusters. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;67:085404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.085404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.-X., Feng X.-J., Zhang M., Luo Y.-H. Structural growth sequences and electronic properties of lanthanum-doped-gold clusters. J. Clust. Sci. 2010;21:701–711. doi: 10.1007/s10876-010-0293-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-R., Kuang X.-Y., Zheng B.-B., Li Y.-F., Wang S.-J. Equilibrium geometries, stabilities, and electronic properties of the bimetallic M2-doped Aun (M = Ag, Cu; n = 1−10) clusters: comparison with pure gold clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011;115:569–576. doi: 10.1021/jp108695z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-R., Kuang X.-Y., Shao P., Li C.-G., Wang S.-J., Li Y.-F. A systematic search for the structures, stabilities, and electronic properties of bimetallic Ca2-doped gold clusters: comparison with pure gold clusters. J. Mol. Model. 2012;18:1333–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00894-011-1154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-R., Kuang X.-Y., Zheng B.-B., Wang S.-J., Li Y.-F. Ab initio calculation of the geometries, stabilities, and electronic properties for the bimetallic Be2Aun (n = 1–9) clusters: comparison with pure gold clusters. J. Mol. Model. 2012;18:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s00894-011-1051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.R., Bai T.T., Jia L.N., Xin W., Hu Y.F., Zheng X.S., Hou S.T. Probing the structural and electronic properties of neutral and anionic lanthanum-doped silicon clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:28561–28568. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b07184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Xu Y., Chen P., Yuan Y., Qian Y., Li Q. Structural and electronic properties of medium-sized beryllium doped magnesium BeMgn clusters and their anions. Results Phys. 2021;26:104341. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B.-C., Deng P.-J., Xiong S.-Y., Dai W., Zeng L., Guo J. Au5Br: a new member of highly stable 2D-type doped gold nanomaterial. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021;194:110446. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2021.110446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.