Highlights

-

•

A novel elastase inhibitory peptide FFVPF was identified from defatted walnut meal.

-

•

Molecular docking revealed the mechanisms of inhibition effect of FFVPF on elatase.

-

•

FFVPF exerted the potential as an inhibitor of elastase.

-

•

FFVPF can resist the degradation of digestive enzymes in the gastric environment.

Keywords: Walnut meal, Elastase inhibitory activity, Inhibitor based-peptide, Molecular docking, Gastrointestinal digestion

Abstract

This study aimed to isolate bioactive peptides with elastase inhibitory activity from walnut meal via ultrasonic enzymatic hydrolysis. The optimal hydrolysis conditions of walnut meal protein hydrolysates (WMPHs) were obtained by response surface methodology (RSM), while a molecular weight of<3 kDa fraction was analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and 556 peptides were identified. PyRx virtual screening and Autodock Vina molecular docking revealed that the pentapeptide Phe-Phe-Val-Pro-Phe (FFVPF) could interact with elastase primarily through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and π-sulfur bonds, with a binding energy of −5.22 kcal/mol. The verification results of inhibitory activity showed that FFVPF had better elastase inhibitory activity, with IC50 values of 0.469 ± 0.01 mg/mL. Furthermore, FFVPF exhibited specific stability in the gastric environment. These findings suggest that the pentapeptide FFVPF from defatted walnut meal could serve as a potential source of elastase inhibitors in the food, medical, and cosmetics industries.

1. Introduction

Walnut meal is a by-product produced by the walnut oil industry; it is rich in dietary fiber, polyphenols, and protein. It is made up of approximately 40–45 % crude proteins, which are rich in essential amino acids needed by the human body. Walnut meal also has a significant amount of arginine (Arg), glutamic acid (Glu), and aspartic acid (Asp), with respective estimates of 13.36 %, 24.06 %, and 10.11 % (Zhu et al., 2018). Therefore, walnut meal is considered a good raw material for preparing bioactive peptides. However, due to its bitter taste and poor sensory, it has limited direct applications and is typically used as animal feed or discarded (Bakkalbasi, Meral, & Dogan, 2016). Walnut meal deep processing has made possible the continuous preparation of bioactive walnut peptides with different physiological functions. Studies have confirmed that bioactive peptides designed from walnut protein sources have the following physiological properties: they are easy to digest and absorb, promote microbial fermentation, and possess antioxidant activity (Moghadam, Salami, Mohammadian, Emam-Djomeh, Jahanbani, & Moosavi-Movahedi, 2020). Moreover, two xanthine oxidase inhibition peptides (WPPKN and ADIYTE) have been purified from walnut meal hydrolysates by Li et al. (2019). A potent angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptide that reduced blood pressure has also been identified in defatted walnut meal.

Elastase is a protease belonging to the chymotrypsin family. It is responsible for degrading dermal structural components, such as elastin. After elastin breaks, the skin begins to sag and wrinkle (Li et al., 2020). Elastase is also associated with many human diseases. A literature survey indicates that excessive elastase release can cause tissue hydrolysis and damage the alveolar structure during acute lung injuries. In contrast, increased macrophage elastase activity can promote rheumatoid arthritis (Liu et al, 2004). Therefore, it is important to research elastase inhibitors for their potential applications in food, medicine, and cosmetics, among other fields. Bioactive peptides can serve as natural elastase inhibitors and are cheap and safe. This makes them ideal raw materials for preparing elastase inhibitors, and their inhibition mechanism has been preliminarily researched. Sorghum polypeptides with molecular weights of 0–3 kDa were reported to have elastase inhibitory activity similar to glutathione (Castro-Jácome et al., 2021). Four peptides with elastase inhibitory ability were purified and identified from bovine elastin hydrolysate (Liu, Su, Zhou, Zhang, Zheng, & Zhao, 2018). Cyclic peptides with strong elastase inhibitory ability were isolated from marine cyanobacteria metabolites, and their activities were related to the particular residues in the structure (Keller, Canuto, Liu, Koehnke, O'Donoghue, & Gerwick, 2020). Although elastase inhibitors peptides have been extensively investigated in a variety of sources, especially animals and microorganisms, few peptides of plant origin have been reported. Given that these peptides are natural, cheap, and non-toxic when used in food, they are considered an ideal source of elastase inhibitors. Through animal experiments, researchers have found that walnut protein hydrolysate can improve UV-induced skin photoaging, which is related to elastase activity (Xu, Wang, Liao, Liao, Li, & Zhao, 2020). However, walnut peptides could inhibit enzyme activity, though the inhibitory effect of walnut peptides on elastase remains unclear and requires further exploration. Molecular docking refers to the mutual recognition of two molecules through structural complementarity and energy matching. This is an effective silico tool for complex interactions between receptors and ligands and for virtual screening (Yu et al., 2021). Recently, molecular docking has been widely used in the screening and discovery of natural small molecule active compounds, and has proved to be an important tool for computer-assisted receptor-ligand binding prediction of active peptides (Yu et al., 2020). Molecular docking technology was used to screen out antioxidant peptides from hemp seed protein hydrolysates (HPH) and to identify the possible mechanism of antioxidant activity due to blocking the entrance of the active cavity of myeloperoxidase, confirming that this method is effective (Gao, Li, Chen, Gu, & Mao, 2021). Therefore, molecular docking is a flexible tool to find elastase inhibitors and reveal the underlying mechanisms.

This study was designed to isolate and identify elastase inhibitory peptides from walnut meal protein using alkaline hydrolysis, ultrafiltration, LC-MS/MS identification, and computer simulation. Subsequently, the molecular interaction mechanism between identified pentapeptide FFVPF and elastase molecules was proposed based on the results of virtual screening and molecular docking. Additionally, in vitro gastrointestinal digestion stability was measured by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) after the chemical synthesis of the pentapeptide.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Walnut meal with a protein content of 77.21 ± 2.81 %, which was treated by hydraulic pressure, was provided by Huangjinlong Edible Oil Co., ltd. (Hebei, China). Elastase, formic acid with chromatographic purity, and N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Ala-p-nitroaniline were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, USA). Epigallocatechin-gallate (EGCG), pepsin, and trypsin were obtained from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., ltd. (Shanghai, China). Alcalase (62000 U/g) was purchased from Novozymes (China) Biotechnology Co. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade acetonitrile was provided by Beijing Mreda Technology Co., ltd. (Beijing, China). HPLC grade trifluoroacetic acid was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, USA). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of walnut meal protein hydrolysates (WMPHs)

Alkaline protease was chosen as the target enzyme based on a primary experiment. The hydrolysis conditions were determined according to the preliminary single factor and response surface experiments (Supplementary data 1). Walnut meal protein (WMP) was isolated according to the method described by Mao and Hua (Mao & Hua, 2012). The resulting WMP powder, with a protein content of 77.21 ± 2.81 %, was mixed with distilled water at a ratio of 1:20 (v/w), and the mixture was treated with ultrasonication at 400 W for 20 min. During the ultrasonication process, the No.6 ultrasonic horn was selected, and the ultrasonic gap was set to 2 s. The pH of the reaction system was adjusted to the optimum pH of the hydrolase with 1 M Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 1 M HCL, after which 1 % (w/w, enzyme/substrate) alkaline protease was added. The resulting mixture was incubated for 4 h and heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min to inactivate the enzyme. The pH of the enzymatic hydrolysate was then adjusted to 7.0, and the sample was centrifuged at 6000 × g for 20 min at 4℃. The supernatant was a polypeptide solution, lyophilized with a Biosafer-12A lyophilizer (Nanjing Biosafer Biotechnology Co. ltd, China) and stored until use.

2.3. Determination of elastase inhibitory activity

The elastase inhibition test was slightly modified according to the method described by Liu Yang et al. (2019). First, 0.5 mg/mL EGCG and the sample were prepared with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.0). All the assays were performed in three independent experiments, after which 50 μL reaction substrate N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Ala-p-nitroaniline (1 mM) and 100 μL sample (or Tris-HCl buffer were used as the negative control) were successively injected into 96-well plates and mixed evenly. The absorbance was recorded as A1 and A0 at 410 nm. It was then incubated at 25℃ for 5 min with 50 μL elastase (100 mU/mL), and 10 μL HCl (2 M) was added to terminate the reaction. The absorbance of the reaction product (p-nitroaniline) was recorded at 410 nm, which was denoted as A2 and A3. The semi-inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the samples to elastase was calculated according to the experimental results, and the elastase inhibition activity was calculated by:

Elastase inhibition activity (%) = × 100

where A0 is the absorbance of the control group before the reaction, A1 is the absorbance of the sample group before the reaction, A2 is the absorbance of the sample group after the reaction, and A3 is the absorbance of the control group after the reaction.

2.4. Separation and identification of elastase inhibitory peptides from WMPHs

The hydrolysates were separated using a Vivaflow 50 Tangential flow ultrafiltration & concentration device (Sartorius, Germany) with molecular weight (MW) cut-off values of 10, 5, and 3 kDa. All fractions were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C. The amino acid sequence and molecular weight of the fraction with the highest elastase inhibitory activity were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, which was separated by an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) interfaced with an Orbitrap Elite Hybrid Ion Trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The mass spectrometer was equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI) nanospray source in the positive ion mode. The most active fraction was pretreated with reduction-alkylation, passed through a pre-column (Acclaim PepMap C18, 300 μm × 5 mm, 5 μm), and injected into the analytical column (Acclaim PepMap C18, 75 μm × 150 mm, 3 μm) at 300 nL/min. Eluent A consisted of 0.1 % (v/v) formic acid in water, while Eluent B was prepared by mixing 0.1 % (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile. The elution gradient was 0–8 min, 6–9 % B; 8–24 min, 9–14 % B; 24–60 min, 14–30 % B; 6–75 min, 30–40 % B; 75–78 min, 40–95 % B. The parameters were as follows: The resolution of the primary mass spectrum = 70,000; AGC target = 3e6; scan range = 100–1500 m/z. The resolution of the secondary mass spectrum = 17500; AGC target = 1e5; scan range = 50–1500 m/z. The raw mass spectra data were compared with the Juglans Regia database of Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/) using Mascot software (Matrix Sciences, London, UK) searches.

2.5. Amino acid composition analysis and peptide synthesis

The acid hydrolysis method was used to determine the amino acid composition of walnut meal and components of 0–3 kDa molecular weight with an automatic amino acid analyzer (L-8900, Hitachi, Japan). 10 mL 50 % (v/v) concentrated hydrochloric acid was added to each sample (100.0 mg), and the mixture was placed at 110℃ for 22 h. The clean liquid was then placed in a 50 mL test tube, and water was added to make the volume constant. 1 mL liquid was sucked into a vial and evaporated in a vacuum drying oven at 55℃ for 4 h. A standard solution with seventeen amino acids (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) was used as the external standard. Additionally, the peptides were screened based on the results of amino acid analysis and previous literature.

Yuantai Biotechnology Co., ltd. (Nanjing, China) synthesized the peptide Phe-Phe-Val-Pro-Phe (FFVPF) using the Fmoc solid-phase method based on the sequence identified measured in the previous step. The purity of the synthetic peptides was detected above 95 % by RP-HPLC.

2.6. Virtual screening and molecular docking

Molecular docking studies were performed at Discovery Studio 2019 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA), with slight modifications that were described earlier (Liu, Su, Zhou, Zhang, Zheng, & Zhao, 2018). AutoDock Vina 4.0 was used to detect the molecular interaction between polypeptide and elastase. The 3D structure of peptides within 10 amino acids was generated by ChemDraw. The X-ray crystal structure of porcine elastase (PDB ID: 1ELB) was downloaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/), and the structure of the enzyme was pretreated by hydrogenation and saved in pdbqt format. Using the PyRx (https://pyrx.sourceforge.io) platform, elastase receptor proteins and ligands were prepared (Dallakyan & Olson, 2015). All amino acid residues remained rigid, the ligands were flexibly treated, and the docking box (40 Å × 40 Å × 40 Å) covered as many protein surfaces as possible during the docking process. A grid spacing of 0.375 Å was used to enclose the active site. Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used for docking calculation, and the search parameter was set to 100 times. Subsequently, the docking model with the lowest binding energy of ligand in the binding pocket of protein was selected as the best model. The Vina score was used as the predictive affinity of peptide binding to elastase (calculated in kcal/mol).

2.7. Investigation of digestive stability of peptide fragment

An in vitro simulated digestion experiment was designed to assess/evaluate the stability of the selected peptide during gastrointestinal digestion (Sophie et al., 2013, Tavares et al., 2011). Primarily, 1 % (w/w) porcine pepsin solution was prepared, and the pH was adjusted to 2.0 with 0.1 mM KCl-HCl. The peptide was then added at an enzyme: substrate ratio of 1:30 (w/w), and the mixture oscillated at 37℃ for 2 h at 170 rpm. After simulated gastric digestion, the enzyme was eliminated in a boiling water bath for 10 min, centrifuged at 6000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. Trypsin and pancreatin were dissolved in 0.1 mol/L NaHCO3 at a ratio of 1: 1 (w/w) to prepare simulated intestinal fluid (SIF), which was mixed with the supernatant obtained after simulated gastric digestion at a ratio of 1: 1 (v/v), adjusted pH to 7.5. After incubation with SIF for 4 h, the reaction mixture was boiled to inactivate the enzyme and centrifuged (6000 × g, 15 min) to remove the enzyme, after which the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. The structural changes of FFVPF before and after two stage-hydrolysis processes were determined by RP-HPLC (LC-2A, Shimadzu, Japan). Specifically, the FFVPF solution was injected into the chromatographic column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, WondaSil C18 Superb, Shimadzu, Japan). Solvent A was a mixture of water/trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 %, v/v), while solvent B was a mixture of acetonitrile/trifluoroacetic acid (0.1 %, v/v). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, and the detection wavelength was 220 nm.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate, and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences (P < 0.05) were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Origin 2019 software was used for mapping. Design Expert 12 software was used to analyze the results of the Box-Behnken test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation of WMPHs

The biological characteristics of protein hydrolysates depend on the degree of hydrolysis, protein substrate, the conditions used in the hydrolysis process (temperature and enzyme/substrate ratio), and the specificity of enzymes used for hydrolysis (Chalamaiah, Kumar, Hemalatha, & Jyothirmayi, 2012). In this work, WMPHs with a yield of 52.75 ± 1.64 % were obtained from walnut meal with a single factor experiment and Box-Behnken response surface methodology, and their ability to inhibit elastase was evaluated. The IC50 value of the enzymatic hydrolysate prepared under the optimized conditions was 2.68 ± 0.127 mg/mL (Supplementary data 1), suggesting that WMPHs contain elastase inhibitory peptides.

3.2. Purification and identification of elastase inhibitory peptides from WMPHs

The molecular weight (MW) of bioactive peptides determines whether the resulting bioactive peptides have the desired functional properties. Ultrafiltration is a pressure-driven membrane separation technology that can separate hydrolysates into multiple components based on MW. EGCG, a known high-efficiency elastase inhibitor, was used as a positive control (Kim, Uyama, & Kobayashi, 2004). To precisely position peptides with a potential elastase inhibitory effect, WMPHs were ultrafiltrated by 3 kDa, 5 kDa, and 10 kDa cut-off membranes, and the elastase inhibitory effect of the four resulting fractions was determined. As shown in Table 1, the lowest elastase inhibitory activity was found in 3–5 kDa fractions, followed by 5–10 kDa and > 10 kDa fractions, but the difference was not significant. The 0–3 kDa fraction exhibited a potent effect characterized by an IC50 of 1. 800 ± 0. 069 (P < 0.05). Similarly, an ultrafiltration system was used to intercept and separate napin protein hydrolysates in rapeseed and found that components with MW<1 kDa had a stronger inhibitory effect on dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP-IV) than other components (Xu, Yao, Xu, Jiang, Ju, & Wang, 2019). Of the three components with different molecular weights obtained by ultrafiltration, components with<3 kDa had higher antioxidant activity than the mixture before ultrafiltration and other ultrafiltration components, and ultrafiltration was an effective means to enrich the components with high activity (Wang, Li, Chi, Ma, Luo, & Xu, 2013). Therefore, the 0–3 kDa fraction was chosen for further amino acid sequencing and liquid chromatography analysis.

Table 1.

The semi-inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of enzymatic hydrolysates with different molecular weights on elastase.

| Substance | Elastase IC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| 0–3 kDa | 1.800 ± 0.069c |

| 3–5 kDa | 3.621 ± 0.279a |

| 5–10 kDa | 3.023 ± 0.159b |

| >10 kDa | 2.890 ± 0.263b |

| EGCG | 0.209 ± 0.007d |

Notes: Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent determinations, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

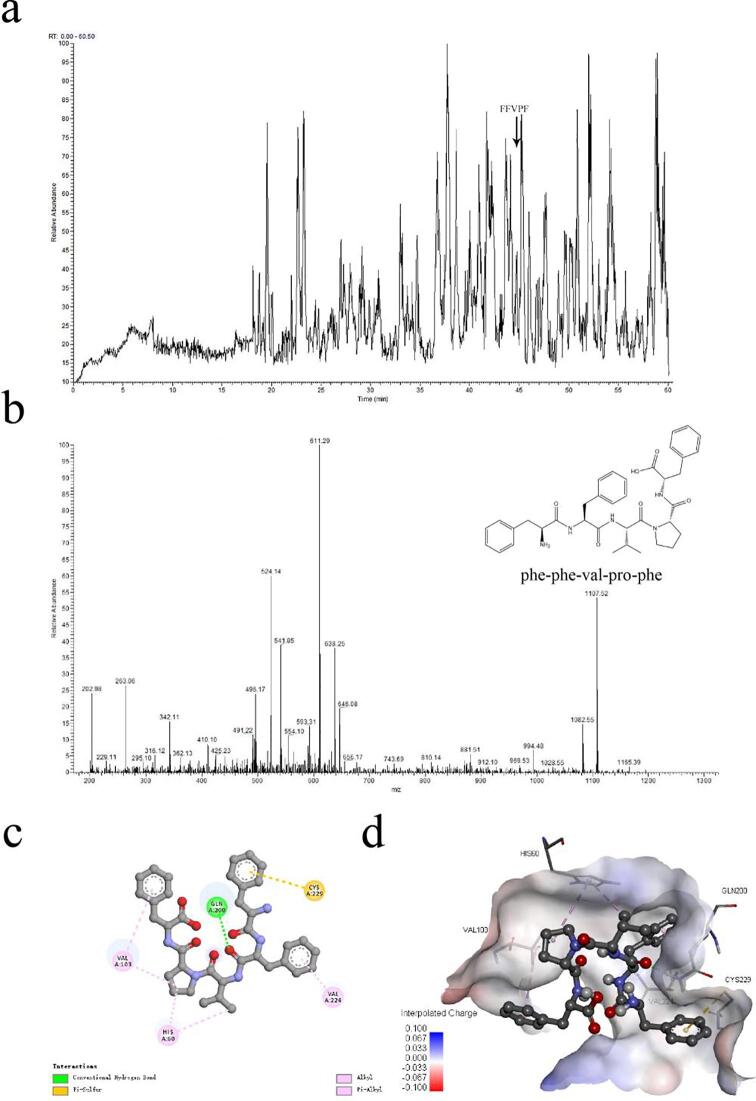

Analysis of the 0–3 kDa fraction by HPLC-MS/MS attempted to pinpoint the fragments likely responsible for this bioactivity. The base peak chromatogram (BPC) is shown in Fig. 1a. We searched for peptide sequences in a database of Juglans Regia and identified a total of 556 unique peptides, with confidence ≥ 95 %.

Fig. 1.

(a) The base peak chromatogram of 0–3 kDa. (b) Chemical structure and MS/MS spectrum of peptide FFVPF. (c) The best conformational interaction between elastase and peptide FFVPF (plane). Hydrogen bonds are represented with dashed green lines, pi-sulfur interactions with dashed yellow lines and hydrophobic interactions with dashed pink lines. (d) The best conformational interaction between elastase and peptide FFVPF (3D). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Amino acid composition analysis

The amino acid composition of walnut meal and its fraction with MW of 0–3 kDa was determined and is shown in Table 3. Walnut meal has a large proportion of aspartic acid (10.10 %), glutamic acid (23.52 %), and arginine (15.63 %), while 0–3 kDa fraction has a large proportion of aspartic acid (9.73 %), glutamic acid (17.63 %), leucine (10.26 %), and arginine (12.48 %). The hydrophobic amino acid compositions of walnut meal and 0–3 kDa fractions are 33.67 % and 41.17 %, respectively. The hydrophobic amino acid composition of walnut meal and 0–3 kDa components was 33.67 % and 41.17 %, respectively, which was consistent with the unique amino acid composition of elastin that has been previously reported (Rasmussen, Bruenger, & Sandberg, 1975). Positively charged alkaline amino acids, such as Arg, can act as strong hydrogen donors (Sarmadi & Ismail, 2010). After ultrafiltration, the alanine (Ala) content increased from 4.29 % to 6.69 %, the valine (Val) content from 5.18 % to 6.80 %, the leucine (Leu) content from 7.81 % to 10.26 %, and the phenylalanine (Phe) content from 4.65 % to 5.97 %. This could affect the inhibitory activity of polypeptides on elastase. It has been reported that elastase has a potential affinity for peptides containing Glycine (Gly), Ala, Proline (Pro), Val, and Leu amino acid residues. The presence of these amino acid residues is considered to be a potential elastase inhibitor, thereby protecting the skin from the effects of aging (Liu Y., 2019). Aromatic Phe is another amino acid that is important for scavenging free radicals by electron or hydrogen transfer (Elias, Kellerby, & Decker, 2008). In addition, some hydrophobic amino acids such as Leu, Pro, Val, and Ala also contribute to antioxidant activity (Nwachukwu & Aluko, 2019).

Table 3.

Amino acid contents of walnut meal and components of 0–3 kDa fraction.

| Types of amino acids | Walnut meal (g/100 g) | Content percentage(%) | 0 ∼ 3 kDa (g/100 g) | Content percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp | 3.3956 | 10.10 | 4.8386 | 9.73 |

| Thr | 1.0562 | 3.14 | 1.9437 | 3.91 |

| Ser | 1.8578 | 5.53 | 3.2414 | 6.52 |

| Glu | 7.9060 | 23.52 | 8.7680 | 17.63 |

| Gly | 1.7704 | 5.27 | 1.8745 | 3.77 |

| Ala | 1.4409 | 4.29 | 3.3285 | 6.69 |

| Val | 1.7419 | 5.18 | 3.3823 | 6.80 |

| Met | 0.2757 | 0.82 | 0.7315 | 1.47 |

| Ile | 1.2111 | 3.60 | 2.0605 | 4.14 |

| Leu | 2.6243 | 7.81 | 5.1038 | 10.26 |

| Tyr | 1.0569 | 3.14 | 2.1880 | 4.40 |

| Phe | 1.5640 | 4.65 | 2.9709 | 5.97 |

| Lys | 0.9947 | 2.96 | 1.0674 | 2.15 |

| His | 0.7712 | 2.29 | 1.0026 | 2.02 |

| Arg | 5.2547 | 15.63 | 6.2064 | 12.48 |

| Pro | 0.6880 | 2.05 | 1.0220 | 2.06 |

| Hydrophobic amino acid content | 33.67 | 41.17 | ||

3.4. Virtual screening and molecular docking analysis of potential bioactive peptide

Molecular docking is an effective method of studying the interaction between ligands and biological macromolecules (Trott & Olson, 2010). PyRx software and Autodock Vina software were used to judge the strength of the interaction forces and screen the amino acid sequences of 556 identified peptides. Typically, the lower the binding energy score, the stronger the binding ability. In this study, the binding capacity of peptides to elastase was assessed via molecular docking. LC-MS/MS analysis was used to rank the docking energy of the peptides, which is shown in Table 2. Phe, Val, and Leu frequently appeared, which was consistent with the results of the amino acid composition analysis. Among the ten best docking results, FFVPF exhibited the lowest energy value of −7.6 kcal/mol when the root mean square deviation (RMSD) was 0.00, suggesting that this pentapeptide could have the highest binding affinity for the target. The hydrophobic amino acids at the N-terminal were a designated peptide binding site as a competitive inhibitor (Krichen et al., 2018). The chemical structure and secondary mass spectrum of peptide FFVPF are shown in Fig. 1b.

Table 2.

The 10 peptides with the highest docking energy with elastase.

| Peptide sequence | Docking energy(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| FFVPF | −7.6 |

| FRNF | −7.5 |

| NFY | −7.5 |

| WFGV | −7.5 |

| FAF | −7.4 |

| FLAR | −7.4 |

| LFQV | −7.4 |

| LGW | −7.4 |

| TPF | −7.4 |

| VWF | −7.4 |

Moreover, a more rigorous docking mechanism of FFVPF to elastase was studied by receptor-ligand interaction analysis. The 3D and 2D molecular interaction graphs of elastase-FFVPF are shown in Fig. 1c and Fig. 1d. The pentapeptide docked to the active pocket of the enzyme with a binding energy of −5.22 kcal/mol and showed a compact binding pattern. Theoretically, inhibitory peptides can inactivate the enzyme by occupying its active sites or blocking the entrance of the active site cavity (Shih, Chen, Wang, & Hsu, 2019). The elastase docking postures of FFVPF were similar to that previously evaluated for bovine elastin peptides, with five hydrogen bonds between the most active GLPY and the enzyme residues and an absolute docking energy of 6.4 kcal/mol. However, the weakly active peptides PY, GPGGVGAL and GLGPGVG also had one, three and five hydrogen bonds with elastase, respectively. Both of them could strongly interact with elastase, which confirmed that they were effective inhibitors (Liu, Su, Zhou, Zhang, Zheng, & Zhao, 2018). In this study, a total of seven interactions were observed. Five hydrophobic interactions formed between N-terminal second Phe, Val, Pro, Leu, and C-terminal Phe residues of FFVPF and the Val 224, Histidine (His) 60, Val 103, His 60, and Val 103 residues with respective lengths of 4.5144 Å, 4.9085 Å, 3.7357 Å, 3.7709 Å, and 5.1050 Å. These results indicate that FFVPF could enter the hydrophobic elastase channel and block the hydrolysis of elastase to elastin. This is similar to the preference of elastinolytic MMPS for small and medium hydrophobic residues such as Gly, Ala, Leu and Val at the cleavage site P1′, which has been described to be the main determinant for MMP cleavage site specificities (Miekus, Luise, Sippl, Baczek, Schmelzer, & Heinz, 2019). In contrast, FFVPF also interacts with polar amino acids. There was a hydrogen bond between the second Phe at the N-terminal of the peptide and Glutamine (Gln) 200 residue with a bond length of 1.6494 Å; it is very short, indicating that the force is strong. Hydrogen bond interaction plays a vital role in the crystal structure stability of enzyme and ligand complexes and positively affects the inhibitory activity of the substance (Zhong, Sun, Yan, Lin, Liu, & Cao, 2018). Similarly, the interactions between Ginnalin A (GA) and Maplexin J (MJ) of gluconol core gallate (GCG) with elastase were mainly hydrogen bond and hydrophobic (Liu et al., 2020). The binding of FFVPF to elastase also formed a π-sulfur interaction between the first Phe at the N-terminal of the peptide and the cysteine (Cys) 229 residue, with a bond length of 4.6619 Å. These interactions caused the peptide to form stable complexes with proteins, which could lead to higher elastase inhibitory activity. On the other hand, FFVPF has a shorter peptide chain length and theoretically more stable activity.

3.5. Elastase inhibitory activity of the identified peptide

The activities of the synthetic peptides FFVPF were verified by our experiments, and the semi-inhibitory concentrations of both FFVPF and the positive control as they relate to elastase are shown in Table 4. FFVPF exhibited good elastase inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 0.469 ± 0.010 mg/mL, indicating that it could be used as a future functional bioactive peptide. As discussed above, elastase showed hybrid affinity to Gly, Ala, Pro, Val, and Leu. In this study, pentapeptide FFVPF is a straight chain without a special structure, and the first position of the N-terminal was a hydrophobic amino acid that was conducive to generating the inhibitory peptide (Krichen et al., 2018). There is a Pro residue at the second position of the C-terminal; it has been reported that Pro plays an important role in synthesizing human collagen and elastin (Chow, Boyd, Iruela-Arispe, Wrenn, Mecham, & Sage, 1989). Two peptides (MGWCTASVPPQCYG and MGWCTASVPPQCYG(GAl)7) were also synthesized that contained G, V, and P residues based on the reaction site loop of Bowman-Birk protein with elastase inhibitory activity; the IC50 value of these two peptides was 18.7 and 16.0 μM, respectively (Vasconcelos, Azoia, Carvalho, Gomes, Gueebitz, & Cavaco-Paulo, 2011). These could account for the high elastase inhibitory activity of FFVPF. In addition, several studies have shown the importance of aromatic amino acids for inhibiting elastase. For example, Zhang et al. (2022) screened elastin peptides from tuna proteins and found that Phe containing peptides at the C-and N-terminus of the peptide chain showed significant inhibitory activation, which was consistent with the hydrophobic interaction between Phe and hydrophobic side chains located at the active site of elastase during molecular docking. Therefore, the peptide FFVPF was selected to further explore its properties.

Table 4.

The semi-inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of the synthesis peptide on elastase.

| Substance | Elastase IC50(mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| FFVPF | 0.469 ± 0.010a |

| EGCG | 0.209 ± 0.007b |

Notes: Values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent determinations, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.6. Stability of elastase inhibitory peptide

One important property of polypeptides in the gastrointestinal tract is their stability. Bioactive peptides either remain stable after gastrointestinal digestion, maintain bioactivity after passing through the intestinal wall, or are converted into other active forms after digestion. Pepsin and trypsin can hydrolyze some peptides into smaller peptides or even amino acids, decreasing the concentration of these peptides and affecting their biological activity (Wang, Wang, & Li, 2016). RP-HPLC was used to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze the digestive stability of FFVPF. Fig. 2a shows the liquid chromatogram of FFVPF (1 mg/mL) before digestion. The peak time was 10.70 min, and the peak shape was narrow without tailing. The low pH of gastric juice is generally thought to be one of the main reasons why bioactive peptides become inactive before they are absorbed by the intestine and perform specific physiological functions (Singh & Vij, 2018). Fig. 2b shows the liquid chromatogram of FFVPF digested by simulated gastric fluid for 2 h. The peak area decreased at 10.70 min, and a new peak was generated at about 2.50 min. Based on the calculated peak area and standard curve, the retention rate was 87.48 ± 1.24 %. This suggests that the peptide was partially decomposed, and FFVPF could resist digestion in gastric fluid. Pepsin mainly hydrolyses carboxy-terminated peptide bonds containing hydrophobic amino acid residues such as Phe, tryptophan (Trp), and tyrosine (Tyr). The resulting peptide sequence is Phe-Phe-Val-Pro-Phe, indicating that pepsin in gastric juice could partially degrade into smaller peptide fragments (Chiang, Tsou, Tsai, & Tsai, 2006). However, there were significant changes in the peptide after gastrointestinal digestion (Fig. 2c). No peak was generated at about 10.7 min, and a peak with an immense response value appeared at 2.00–4.00 min, indicating that the peptide was almost entirely hydrolyzed by digestive enzymes. The substances corresponding to the new peak were the decomposition products of short peptides. The stability of bioactive peptides in the simulated gastrointestinal fluid was related to their sequence and structure, the polypeptides with a circular structure were more stable, and the long peptide chain easily degraded due to its large number of peptide bonds and high structural flexibility (Wang, Yadav, Smart, Tajiri, & Basit, 2015). It has also been reported that low molecular weight peptides are easily degraded by proteases (Shen & Matsui, 2017). Therefore, if peptide FFVPF were to be included in anti-aging foods, adding certain food matrix components could promote its stability under gastrointestinal digestive conditions.

Fig. 2.

RP-HPLC of FFVPF before and after simulated digestion. (a) RP-HPLC of FFVPF. (b) RP-HPLC of FFVPF after gastric digestion for 2 h. (c) RP-HPLC of FFVPF after gastric digestion for 2 h and intestinal digestion for 4 h.

4. Conclusion

This study reports, for the first time, the elastase inhibitory activity and the underlying elastase inhibitory mechanisms of peptides derived from walnut meal proteins. After a series of chromatographic separation and purification steps, a novel elastase inhibitory peptide was identified with the sequence Phe-Phe-Val-Pro-Phe (FFVPF). Molecular docking simulation revealed that effective interaction between FFVPF and active elastase site occurred mainly through three interaction forces and that the conformation of the pentapeptide-elastase complex is stable. In addition, a lower molecular weight, higher hydrophobic amino acids, and Leu could contribute to a high capacity for elastase inhibition. Excellent elastase inhibitory activity was observed for chemically synthesized FFVPY, indicating that this pentapeptide could be a promising elastase inhibitor. Finally, in vitro gastrointestinal digestion simulation demonstrated the significant degree of stability of FFVPF in the gastric environment. These results suggest that FFVPF is a potent, natural elastase inhibitor and could be used in the industrial production of foods and dietary supplements designed to slow the aging process of the skin. However, FFVPF has a bitter taste, and further studies are needed to address problems associated with its application. Future work should investigate methods of masking the bitter taste, as well as the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of bioactive peptides stabilized in vivo.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFD1002400) and National promotion project of scientific and technological achievements in forestry and grassland (2020133135).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochms.2022.100139.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bakkalbasi E., Meral R., Dogan I. Bioactive compounds, physical and sensory properties of cake made with walnut press-cake. Journal of Food Quality. 2016;38(6):422–430. doi: 10.1111/jfq.12169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Jácome T.P., Alcántara-Quintana L.E., Montalvo-González E., Chacón-López A., Kalixto-Sánchez M.A., del Pilar Rivera M.…Tovar-Pérez E.G. Skin-protective properties of peptide extracts produced from white sorghum grain kafirins. Industrial Crops and Products. 2021;167 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah M., Kumar B.D., Hemalatha R., Jyothirmayi T. (FPH): Proximate composition, amino acid composition, antioxidant activities and applications: A review. Food Chemistry. 2012;135:3020–3038. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang W.D., Tsou M.J., Tsai Z.Y., Tsai T.C. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor derived from soy protein hydrolysate and produced by using membrane reactor. Food Chemistry. 2006;98:725–732. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow M., Boyd C.D., Iruela-Arispe M.L., Wrenn D.S., Mecham R., Sage E.H. Characterization of elastin protein and mRNA from salmonid fish (Oncorhynchus kisutch) Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B-Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 1989;93(4):835–845. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(89)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallakyan S., Olson A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx Methods. Molecular Biology. 2015;263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias R.J., Kellerby S.S., Decker E. Antioxidant activity of proteins and peptides. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2008;48:430–441. doi: 10.1080/10408390701425615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.X., Li T.G., Chen D.D., Gu H.F., Mao X.Y. Identification and molecular docking of antioxidant peptides from hemp seed protein hydrolysates. LWT-Food Science & Technology. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller L., Canuto K.M., Liu C., Koehnke J., O'Donoghue A.J., Gerwick W.H. Tutuilamides A-C: Vinyl-chloride-containing cyclodepsipeptides from marine cyanobacteria with potent elastase inhibitory properties. ACS Chemical Biology. 2020;15(3):751–757. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Uyama H., Kobayashi S. Inhibition effects of (+)-catechin-aldehyde polycondensates on proteinases causing proteolytic degradation of extracellular matrix. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;320(1):256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichen F., Sila A., Caron J., Kobbi S., Nedjar N., Miled N.…Bougatef A. Identification and molecular docking of novel ACE inhibitory peptides from protein hydrolysates of shrimp waste. Engineering in Life Sciences. 2018;18(9):682–691. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201800045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., DaSilva N.A., Liu W., Xu J., Dombi G.W., Dain J.A.…Ma H. Thymocid®, a standardized black cumin (Nigella sativa) seed extract, modulates collagen cross-linking, collagenase and elastase activities, and melanogenesis in murine B16F10 melanoma cells. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2146–2162. doi: 10.3390/nu12072146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Shi C., Wang M., Wang Z., Yao M., Ren J. Tryptophan residue enhances in vitro walnut protein-derived peptides exerting xanthine oxidase inhibition and antioxidant activities. Journal of Functional Foods. 2019;53:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Xu Y., Kirk R.D., Li H., Li D., DaSilva N.A.…Ma H. Inhibitory effects of skin permeable glucitol-core containing gallotannins from red maple leaves on elastase and their protective effects on human keratinocytes. Journal of Functional Foods. 2020;75 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Sun H., Wang X., Koike T., Mishima H., Ikeda K.…Fan J. Association of increased expression of macrophage elastase (matrix metalloproteinase 12) with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(10):3112–3117. doi: 10.1002/art.20567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. (2019). Study on anti-skin photoaging effect of elastin peptide and its mechanism. Doctoral Dissertation of South China University of Technology.

- Liu Y., Su G., Zhou F., Zhang J., Zheng L., Zhao M. Protective effect of bovine elastin peptides against photoaging in mice and identification of novel antiphotoaging peptides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66(41):10760–10768. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Hua Y. Composition, structure and functional properties of protein concentrates and isolates produced from walnut (Juglans regia L.) International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13(2):1561–1581. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miekus N., Luise C., Sippl W., Baczek T., Schmelzer C.E.H., Heinz A. MMP-14 degrades tropoelastin and elastin. Biochimie. 2019;165:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam M., Salami M., Mohammadian M., Emam-Djomeh Z., Jahanbani R., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A. Physicochemical and bio-functional properties of walnut proteins as affected by trypsin-mediated hydrolysis. Food Bioscience. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu I.D., Aluko R.E. Structural and functional properties of food protein-derived antioxidant peptides. Journal of Food Biochemistry. 2019;43:e12761. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen B.L., Bruenger E., Sandberg L.B. A new method for purification of mature elastin. Analytical Biochemistry. 1975;64(1):255–259. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadi B.H., Ismail A. Antioxidative peptides from food proteins: A review. Peptides. 2010;31(10):1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Matsui T. Current knowledge of intestinal absorption of bioactive peptides. Food & Function. 2017;8(12):4306–4314. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01185G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Y., Chen F., Wang L., Hsu J. Discovery and study of novel antihypertensive peptides derived from Cassia obtusifolia seeds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2019;67(28):7810–7820. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B.P., Vij S. In vitro stability of bioactive peptides derived from fermented soy milk against heat treatment, pH and gastrointestinal enzymes. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2018;91:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sophie G., Holly T., Harjinder S. In vitro gastric and intestinal digestion of a walnut oil body dispersion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61(2):410–417. doi: 10.1021/jf303456a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares T., Contreras M.D., Amorim M., Pintado M., Recio I., Malcata F.X. Novel whey-derived peptides with inhibitory effect against angiotensin-converting enzyme: In vitro effect and stability to gastrointestinal enzymes. Peptides. 2011;32:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos A., Azoia N.G., Carvalho A.C., Gomes A.C., Gueebitz G., Cavaco-Paulo A. Tailoring elastase inhibition with synthetic peptides. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;666:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Li L., Chi C., Ma J., Luo H., Xu Y. Purification and characterisation of a novel antioxidant peptide derived from blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) protein hydrolysate. Food Chemistry. 2013;138(2–3):1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Wang B., Li B. Bioavailability of peptides from casein hydrolysate in vitro: Amino acid compositions of peptides affect the antioxidant efficacy and resistance to intestinal peptidases. Food Research International. 2016;81:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yadav V., Smart A.L., Tajiri S., Basit A.W. Toward oral delivery of biopharmaceuticals: An assessment of the gastrointestinal stability of 17 peptide drugs. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015;12(3):966–973. doi: 10.1021/mp500809f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Wang W., Liao J., Liao L., Li C., Zhao M. Walnut protein hydrolysates, rich with peptide fragments of WSREEQEREE and ADIYTEEAGR ameliorate UV-induced photoaging through inhibition of the NF-κB/MMP-1 signaling pathway in female rats. Food & Function. 2020;11(12):10601–10616. doi: 10.1039/D0FO02027C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Yao Y., Xu X., Jiang D., Ju X., Wang L. Identification and quantification of DPP-IV inhibitory peptides from hydrolyzed rapeseed protein-derived Napin, with analysis of the interaction between key residues and protein domains. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2019;67(13):3679–3690. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Ji H., Shen J., Kan R., Zhao W., Li J.…Liu J. Identification and molecular docking study of fish roe-derived peptides as potent BACE 1, AChE, and BChE inhibitors. Food & Function. 2020;11:6643–6651. doi: 10.1039/d0fo00971g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.P., Kang L.X., Zhao W.Z., Wu S.J., Ding L., Zheng F.P.…Li J.R. Identification of novel umami peptides from myosin via homology modeling and molecular docking. Food Chemistry. 2021;344 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Wan H., Han J., Sun X., Yu R., Liu B.…Su X. Ameliorative effect of tuna elastin peptides on AIA mice by regulating the composition of intestinal microorganisms and SCFAs. Journal of Functional Foods. 2022;92 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C., Sun L.C., Yan L.J., Lin Y.C., Liu G.M., Cao M.J. Production, optimization and characterisation of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) gonad. Food & Function. 2018;9(1):594–603. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01388D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Zhu W., Yi J., Liu N., Cao Y., Lu J.…McClements D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Research International. 2018;106:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.