Abstract

Engagement is positively correlated with many educational outcomes. However, engaging learners in online learning is often challenging. In this study, a conceptual framework comprising five interrelated factors (instructors, learners, content, technology, and environments) was proposed. The purpose of the study was to explore how learners could be engaged by following the conceptual framework in synchronous online learning. Fifty-five adult learners took part in the study. Specific strategies were applied in four classes. A survey with 38 five-point Likert scale items and an open-ended question was administered. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analysed. Results showed that instructors, learners, and content were the core factors affecting learners’ engagement. Comparatively, the learners’ engagement was less affected by the factors of technology and environments. Results further showed that useful strategies to engage learners included providing opportunities for instructors and peers to interact frequently; having relevant content that could apply to practice; involving interactive activities like group discussions and peer feedback; and having informal conversations with individual learners. This study suggests that future studies can investigate facilitating synchronous online discussions, establishing social connectedness, and using technology to monitor learners’ engagement automatically.

Keywords: Engagement, Synchronous online learning, Social connectedness, Video conferencing, Technology

Introduction

Engagement is the energy and effort that learners devote to learning (Bedenlier et al., 2020). It is a highly researched topic in traditional education as engagement is often positively correlated with many student learning outcomes like academic achievement, persistence, and satisfaction (Fredricks et al., 2004; Meyer, 2014). In online education, engagement is even more important than that in traditional education as learners are often harder to be engaged, and their course completion rates are often lower (Bolliger & Martin, 2018; Hew, 2018; Kurt et al., 2022).

In recent years, synchronous online learning (SOL) has become a common instructional approach and a focus of research in higher education as it allows learners, who are geographically separated, to interact with their instructors and peers in real time. The unique feature was quickly picked up by course instructors during the Covid-19 pandemic. They commonly used SOL to emulate what happens in the classroom (Guo, 2020; McArthur, 2021). But unlike asynchronous online learning, engaging learners in SOL is even more challenging due to its lack of flexibility in time, pace, and duration (Park & Bonk, 2007). The condition is further aggravated by the increase in stress and anxiety brought about by the measures imposed to curb the pandemic outspread (Kee, 2021); and learners are likely to face technical hindrance (Bedenlier, et al., 2020) as well as undue distractions from their home environments (Baxter & Hainey, 2022). All these are some of the problems that need to be addressed when learning online synchronously.

The problems with engagement in SOL have been highlighted in several published studies. These studies commonly identify that the engagement level in SOL was not as high as when lessons were conducted in the physical classroom (Fabriz et al., 2021; Serhan, 2020; UTSA, 2020), and that learners would prefer face-to-face learning if they had a choice (Baxter & Hainey, 2022). Undoubtedly, the pandemic has made online learning the “de facto” mode of learning rather than an option. Therefore, maintaining a sustained level of engagement when delivering SOL becomes crucial (Baxter & Hainey, 2022; Kurt et al., 2022). This concurs well with Baxter and Hainey (2022), who claimed that “for synchronous online educational delivery to be successful, then learner engagement is the key” (p.12).

Instructors who simply apply strategies much like the way carried out in physical classrooms such as using body language as a means to engage students in a synchronous online learning environment (SOLE) often find the method ineffective. This is due to the small window size and inability to see instructors and learners in a full body view. Online instructors therefore need to apply additional strategies that are more suitable for SOL (Heilporn et al., 2021). To this effect, there were studies done at the beginning of the pandemic on strategies for SOL, but no promising results were observed mainly because the instructors and learners involved in the studies were not very well prepared to work in the face of Covid-19. In addition, many researchers of the studies were not practitioners (e.g., Chiu, 2021; Khlaif et al., 2021; Kurt et al., 2022). They just surveyed or interviewed instructors and/or learners rather than applied strategies to engage students. The purpose of this study thus was to investigate how learners in a SOLE could be engaged and to understand how learners perceived the engagement strategies applied.

Conceptual framework

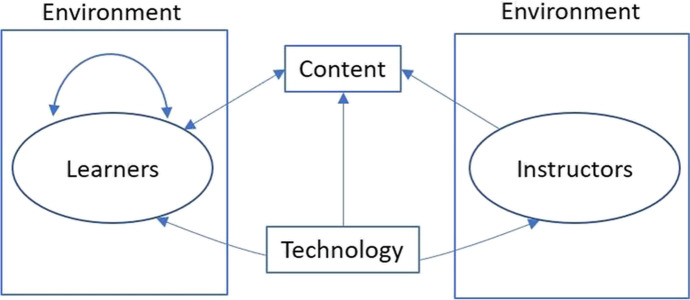

Engagement factors are the broad categories or elements that affect learners’ engagement. In literature, they are often called influences (Lee et al., 2021) or facilitators (Halverson & Graham, 2019). Varied factors have been reported in the literature. For instance, Hew (2018) conducted a study on ten highly rated Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and identified four contributing factors: problem-centric learning, active learning, course resources, and instructor attributes. Lee et al., (2021) did a systematic literature review on online professional learning, and summarised engagement factors into individual, system, and environmental influences. Other empirical studies conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic in K-12 contexts revealed additional factors like digital inequality (Khlaif et al., 2021) and policies (Kurt et al., 2022). Putting the factors together, this study classifies engagement factors into five interrelated categories: instructors, learners, content, technology, and environments. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework that guide the design of the study, which is proposed based on the literature reviewed. The framework illustrates the five factors that affect learners’ engagement and their relationships. The arrows indicate interactive relationships. For instance, learners interact with the instructor via video conferencing technology. The following sections will present the rationale for the factors and engagement strategies associated with each factor.

Fig. 1.

The five interrelated engagement factors

Instructors

Instructors play a fundamental role in engaging learners in any educational context (Wdowik, 2014). To engage learners, instructors must firstly be engaged (Deschaine & Whale, 2017; Hew, 2018; Pittaway, 2012). In online learning, due to the limited window size of streaming videos on the computer screen, instructors often rely heavily on using verbal language as a strategy to engage learners, like greeting learners warmly (Lakhal et al., 2020), using open and inclusive language (Romero-Hall & Vicentimi, 2017), joining the meeting room earlier to welcome learners and address their technical problems in advance (Bower et al., 2015); raising voice (Conklin et al., 2019), and creating a sense of humour (Hew, 2018; Pentaraki & Burkholder, 2017). In addition, instructors can make learners feel cared by providing emotional support (e.g., encouraging learners) (Kurt et al., 2022), incorporating non-verbal behaviours like using smiles or onscreen emoticons to establish immediacy with learners (McArthur, 2021), or even pausing frequently during a lecture to invite questions (Lakhal et al., 2020).

Besides the above strategies, instructors often need professional development to hone their remote lecturing skills. For example, they must learn how to talk in front of a camera (Divanoglou et al., 2018; Lakhal et al., 2020), and how to establish personal contact (Bolliger & Martin, 2018) or address questions from learners (Conklin et al., 2019). In addition, instructors must be proficient with technological tools so that any technical problem can be promptly resolved (Saad & Sankaran, 2020).

Learners

Learners refer to both individual learners and their peers. For individual learners, engagement can be predicted by their motivation, attitude, and self-regulation (Kurt et al., 2022; Landrum, 2020). Motivation is known as a precursor to engagement (Appleton et al., 2006). Based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), learners are motivated when their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Research in SOL shows that involving learners in goal setting and lesson design makes them feel in control of their own learning and thereby increases their autonomy and engagement (Blakey & Major, 2019; Chiu, 2021). In addition, empowering learners to take leadership roles such as being a facilitator of a group discussion or a technology trouble-shooter motivates them and increases their involvement (Angelone et al., 2020; Blakey & Major, 2019; Zydney et al., 2019).

Attitude is closely related to emotional engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004). Learners’ attitudes towards the instructor, course (content and design), and online learning affect their engagement. Learners who are more attached to their instructor or the course often put more effort into subject learning and turn out to be more engaged (Kurt et al., 2022). However, not all learners have favourable attitudes towards online learning (Khlaif et al., 2021), and many prefer face-to-face (f2f) over online learning (Baxter & Hainey, 2022).

For self-regulation, it is not an attribute owned by every learner especially when they learn online (Meyer, 2014). Research has shown that online learning is often more beneficial for learners who have higher self-regulation skills (Boelens et al., 2017). These learners often purposefully set learning goals, monitor learning progress, and actively seek assistance from others (Cho & Cho, 2013). To make learners more self-regulated, research suggests that learners must be equipped with competencies like how to learn online (Meyer, 2014; Tomas et al., 2015), interact with others (Blakey & Major, 2019; Manwaring et al., 2017), establish a social presence to others (Burkholder, 2017), and actively participate in group discussions (Gilmore et al., 2020).

Peers also play an important role in engaging others in a learning community. “Peer support and engagement are likely to be reciprocal” (Fredricks et al., 2004; p. 76). Positive peer support like praise or encouragement can increase learners’ motivation (Montgomerie et al., 2016; Rautanen et al., 2020) and enhance their self-esteem (Tait, 2000). In contrast, a negative peer relation may reduce learner engagement (Liu et al., 2016; Rautanen et al., 2020).

Content

Learning content here broadly refers to subject content (what to learn), which is associated with learning tasks (what to do) and activities (how to do). To engage learners, learning content must be relevant, challenging, and interactive. Based on the ARCS (attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction) motivational model (Keller, 1983), the relevance of learning content is an utmost important factor in increasing learners’ motivation, as it helps to satisfy learners’ personal needs and learning goals (Lee et al., 2021). Moderately challenging content motivates learners without causing high anxiety (Bundick et al., 2014; Pentaraki & Burkholder, 2017). Authentic learning tasks and activities make learners immerse in problem solving in realistic contexts where the knowledge they learn can be realistically applied (Herrington et al., 2003). Lastly, interactive learning content and activities provide opportunities for learners to interact with content and peers and increase their motivation to learn (Deshpande & Chukhlomin, 2017).

More specifically, research indicates that giving learners access to lecture notes like PowerPoint slides before class may reduce learners’ attendance, motivation, or engagement (Baker et al., 2018). In addition, learning activities like group work and e-assessment can motivate and engage students. Group work creates opportunities for learners to interact with peers, which not only increases learners’ understanding of the content but also fosters their relatedness (Bolliger & Martin, 2018; Cavinato et al., 2021; Francescucci & Rohani, 2019). Assessment, on the other hand, gets learners to take a more serious approach towards learning (Holmes, 2018). A study done by Raes et al. (2020) found that online quizzes or polls have the effect of increasing learners’ concentration and motivation. Similar findings from Serrano et al. (2019) reckon that the learners who receive instantaneous feedback after taking quizzes develop deep thinking and knowledge internalization.

Technology

Technology is a unique entity. It can either “enable” or “disable” learning. Very often, technology is a mediating tool in SOL as it enables instructors to deliver course content and provides a means for learners to interact with others (Cloonan & Hayden, 2018; Divanoglou et al., 2018). However, technology often becomes a limiting factor in SOL. This happens when technology fails to function as expected, such as not providing a smooth internet connection or causing technical problems that cannot be overcome promptly (Divanoglou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Olt, 2018). Failing in connectivity has a detrimental impact on learning experiences (Ramsey et al., 2016).

Online learning depends heavily on technological tools to support interactions among all users involved. These tools contain features to connect the instructor with learners, and learners to learners. For communicational interactions, research has emphasised that audio must be clear because any unwanted noise would affect a learner’s concentration to learn (Cloonan & Hayden, 2018; Conklin et al., 2019; Cunningham, 2014; Li et al., 2020). Text chat, another useful feature, allows learners to interact with their instructor and peers without interrupting the progress of a lesson (Raes et al., 2020; Ranga, 2020; Vale et al., 2020). In addition, keeping the camera on enables learners to visually indicate their attendance and participation (Wang & Huang, 2018). Furthermore, the video recording function allows learners to review the recorded video later at a convenient time (Divanoglou et al., 2018; Heilporn & Lakhal, 2021; Vale et al., 2020).

One more useful function is the breakout room. It is particularly useful for activities such as group discussions to take place (Angelone et al., 2020; Conklina et al., 2017). Breakout rooms are virtual rooms where members would not feel much different from their familiar traditional group discussions in classrooms. Other functions in a video conferencing tool such as locking the meeting to prevent non-invitees from joining the meeting, holding attendees in the waiting room to check for identity, and allowing only permitted users to share screens are useful for safeguarding the security and privacy of participants (Conklin et al., 2019; Conklina et al., 2017; Warren, 2020).

Environments

The factor of environments refers to physical environments only. There are three types of environments in SOL, which are the learner’s, the instructor’s, and peers’ environments. The learners’ environment can be a home room, a working office, or a car. Research suggests that the learner’s environment must have the necessary infrastructure such as connected devices, cameras, and microphones to allow for a proper learning condition. It must also be quiet without distractions (Cloonan & Hayden, 2018; Olt, 2018; Vale et al., 2020; Zydney et al., 2019). Wearing headsets with built-in microphones helps minimize interference from a noisy surrounding area (Angelone et al., 2020; Lakhal et al., 2020). Similarly, for the instructor’s and peers’ environments, it is necessary to cut down distractions because they can adversely affect the attention and concentration of other online learners (Frisby et al., 2018).

Besides noise and distractions, instructors can further set ground rules or guidelines to help make the environments conducive for learning. Rules can include asking the learners to test the Internet connection in advance (Bower et al., 2015) so that any problems can be resolved before a lesson, finding a quiet space to learn (Cavinato et al., 2021; Kurt et al., 2022), and always showing respects for the others in a group discussion (Deschaine & Whale, 2017, Zydney et al., 2019). The following section describes how these factors and strategies were incorporated into the design of this study.

Research design

Context

This study was conducted in a Singapore teacher training institute in the semester of August 2021 with 13 teaching weeks. In the first two weeks, because the country was undergoing a lockdown, all courses were conducted in the SOL mode. From the 3rd week onwards, the lockdown was eased due to an improvement of the Covid-19 situation. Learners were then given an option to attend lessons in the physical classroom or continue to do it online. Around 10–20% of the learners chose to be online and the rest opted for the classroom. The delivery of lessons therefore had to be adjusted to allow learning to take place in both onsite and online conditions simultaneously. This type of delivery is known as blended synchronous learning (Wang & Huang, 2018). But the Covid-19 condition took a turn in the 7th week because the infection number went up, causing the remaining sessions of the teaching to go back to fully SOL again.

The participants of the study were from four classes, two of which were learners doing a master’s programme and the other two consisted of learners from a pre-service teacher training programme. One master’s class comprised in-service school teachers and the other was made up of polytechnic lecturers, nurse educators, and instructional designers. Both classes taking two different courses were taught by the same instructor, and each session was conducted in the evenings from 6 to 9 pm. The participants of the pre-service teacher programme were university degree holders, who would become full-fledged teachers after completing the programme. Learning how to use ICT for teaching and learning was mandatory in the two classes taking the same course. These two classes were taught by another instructor. Each session lasted two hours conducted at the regular class time. One of the instructors was a Principal Investigator (PI) of this research study and the other was the Co-PI. Both had at least more than three years of experience conducting SOL. All participants of the study have had some experiences in SOL. The numbers of learners in the four classes were 17, 19, 22, and 20 respectively.

Strategies

The following sections present the specific strategies used in the study to engage learners. It consists of strategies for instructors, learners, content, technology, and environments.

Instructors

Both instructors used the Zoom platform to conduct lectures and group discussions. They adopted the strategies that were presented in the above literature. The instructors frequently used verbal communication to engage learners. They also made efforts to let learners feel warm and welcome. This was especially important as physical proximity was not available. To do this, the instructors always began the lessons about 10 min earlier. The instructors would use this short span of time to greet learners, chat or even have small talks with them to establish a rapport.

Some learners sometimes could appear passive or remain quiet, but if this behaviour persisted for too long, the instructors paused immediately to check for possible issues. The instructors would address the learners by calling their names so that the learners knew the instructors were not simply making a casual call. To reduce unwanted fatigue commonly associated with prolonged sitting in front of a webcam, lessons were scheduled to have short breaks between lectures and group activities.

The instructors implemented group activities normally after a lecture. Breakout rooms were used to put learners into groups. The learners were either assigned to each breakout room by the instructor or chose their own group members. The instructors briefed the learners about what to do while in the breakout rooms such as how to alert the instructors if they had questions to ask or what to do if they ended their discussions earlier. Because breakout rooms in Zoom could only be visited one-at-a-time by the instructors, who had to “float” from one breakout room to another regularly to monitor each group’s progress. During the visit, the instructors would normally just observe the group silently unless there was a need to interrupt for clarifications. The instructors sometimes created additional breakout rooms solely for those who wanted to talk to the instructors in private. This was particularly helpful for those learners who were more introverted or preferred to have conversations in person.

At the end of each lesson, the instructors would leave the Zoom meeting last so that any learner who had a last-minute question would be able to ask. It happened that some learners took this opportunity to ask the instructors for advice on their personal or professional matters.

Learners

The Self-Determination Theory indicates that learners like to be accorded some degree of autonomy for them to proceed with their best way of learning. Following this, the learners in this study exercised some self-options. For example, they could opt to use the text chat function to keep each other informed while the lecture was in progress. They might turn their cameras off temporarily if there was an absolute need to do so although the default requirement was to keep the cameras on always. To foster self-regulation, learners were also constantly reminded of appropriate behaviour and conduct during lectures, group discussions, or Internet disconnection.

Engaging students in group discussions and presentations was always a challenge. Below are some strategies used in this study. First, the learners decided on how they would like to present their group discussion findings. For example, they could choose to present their discussion findings by only a representative or by a few members together. Their choice would maximise the group’s potential to do the best. Next, the learners were required to listen to every other group’s presentation attentively. To ensure this was carried out properly, all other learners were required to fill out an online feedback form on how a group had performed. The peer feedback had a bearing on individual participation and was given to the group for improving the quality of its work.

In addition to peer feedback, the sequence for group presentations could be a concern for some learners. They wanted it to be fair and reasonable. To achieve this, an online shuffling tool was used to randomly assign the sequence to the groups. Each group took turns to “spin” the online shuffling tool. The outcome of the sequence was then posted on the chat box for transparency and a smooth transition from one group to another.

Content

The courses had been offered in prior semesters. In this study, the course content remained unchanged. In each course, the syllabus containing a reading list and other materials was posted on a Learning Management System for learners to access in advance so that they could get themselves prepared before the course began. But the content released in advance did not include PowerPoint slides for lectures, which were only released for learners’ access after each lecture was over. This was to ensure learners paid full attention to the slides projected by the instructor during a lecture and not to be distracted by the slides they already had. In addition, online polls were also used to enhance learners’ understanding and engagement. Poll results were immediately shown to the learners so that any doubts could be clarified instantly.

Technology

Technology played important part in SOL but it could fail unexpectedly. Therefore, having necessary technical checks before the start of each online session was mandatory. This included rebooting notebooks and WIFI routers to ensure they worked at their optimal status. The network connections and video/audio devices were also checked to confirm the connectivity was functioning properly.

Because these checks took time to complete, an instructor planned to play a background music to lighten the mood while learners did the checking. He did it by having the music played on the PowerPoint slide in the Zoom main meeting room. But learners could not hear the music until they were officially allowed into the meeting room. Playing a music was thus discontinued after the first session.

Other strategies included: displaying the learners’ faces on the instructors’ screen side-by-side with the shared content to make the instructors feel like being together with the learners and recording each session with the learners’ consent and sharing it with them later. By doing so, the learners did not worry about missing any segment of a lesson as they could review the recorded video later.

Environments

Noise and unwanted interference should be minimized as they could negatively affect learners’ concentration. In this study, both instructors had a quiet room at home with air conditioning, which was equipped with the required technology and proper lighting to conduct the lessons. The background image in Zoom was chosen to be one that had a complete “blurred out” so that their faces would be at the optimal clarity. They also ensured that their entire faces were not obscure and fully viewable to the learners. Similarly, the learners were expected to have quiet rooms and headsets to ensure communication was clear and undisrupted.

To make the environments conducive, ground rules and expectations including dos and don’ts were set in the first session and repeatedly remined to the learners in each session. The rules included studying in a quiet room; keeping the camera on and the microphone off unless it is instructed otherwise; and checking network connection and devices. Other expectations for the learners included participating in class activities actively, asking questions freely, and using the chat box to communicate with the instructor and peers. The strategies presented above are consolidated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main strategies applied in the synchronous online learning sessions

| Engagement Factors | Main strategies/techniques |

|---|---|

| Instructors |

- Join the meeting room earlier and welcome learners (Bower et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018) - Pause necessarily to invite responses (Lakhal et al., 2020) - Create additional breakout rooms for informal conversations (Kurt et al., 2022) |

| Learners |

- Interact with others using the text chat function or other backchannels (Raes et al., 2020; Ranga, 2020) - Know what and how to do online when connection is broken (Divanoglou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020) - Give peer feedback during group presentations (Cavinato et al., 2021; Deshpande & Chukhlomin, 2017) |

| Content |

- Share readings with learners in advance but give access to lecture slides later (Baker et al., 2018) - Involve group work and discussions (Bolliger & Martin, 2018; Cavinato et al., 2021) - Use online quizzes or polls (Raes et al., 2020) |

| Technology |

- Restart devices and test Internet connection (Divanoglou et al., 2018; Olt, 2018) - Keep cameras on and display faces on the screen (Wang & Huang, 2018) Record streaming videos and share lectures (Heilporn & Lakhal, 2021; Vale et al., 2020) |

| Environments |

- Have essential infrastructure in place (Zydney et al., 2019) - Choose quiet and conducive rooms (Cloonan & Hayden, 2018; Vale et al., 2020) - Use blurred backgrounds (Frisby et al., 2018) |

Ethical process, research question, and data collection

Institutional Review Board’s (IRB) approval was obtained before collecting data. There were no additional requirements or devices needed for the participants to take part in this study. They needed only to take the courses in the usual way. The only difference was that some strategies were purposefully applied in the courses to keep them engaged. In the first session, the participants were briefed about the research purposes. They were also told that a survey would be given at the end of the course. The survey took approximately 15 min to complete. They could opt out freely if they decided not to participate in the survey, otherwise, they could click a “agree” button on the first page of the online survey form to express consent.

The research question of the study was:

What are the learners’ perceptions of the engagement strategies applied?

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected via the survey consisting of 38 five-point Likert scale items (from “5: Strongly agree” to “1: Strongly disagree”) and an open-ended question. The items covered the five engagement factors, in which 7 items were about instructors, 14 about learners, 9 about content, 5 about technology, and the remaining 3 about environments. After reverse coding the three negatively stated items (#7, #8, #34), Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients were calculated, and the coefficients were.888, 0.851, 0.842, 0.720, and 0.639 for the five factors respectively and 0.938 for the entire survey, which indicated that the factors (except the factor of environments having three items only) and the survey were highly reliable (Tuckman, 1999). The open-ended question aimed to collect additional information not covered by the Likert-type items. Descriptive statistics were worked out using software SPSS 28, and thematic analysis of the open-ended question responses was also conducted. To ensure trustworthiness, inductive and deductive thematic analyses were done by two authors using the steps suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). Accordingly, five codes were derived from the thematic analyses with a clear consensus by the two authors, after which, an author continued to analyse the rest of the responses.

Results

Fifty-five learners participated in the survey, of which 33 were from the master’s programme and 22 were from the pre-service programme. Table 2 shows the detailed results of the survey. Figure 2 illustrates the mean scores of the survey items. Figure 3 displays the numbers of codes derived from the open-ended question.

Table 2.

Survey results (N = 55)

| Factor | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructors | 1. The instructor created a warm climate in the Zoom sessions | 4.27 | 0.781 |

| 2. The instructor frequently invited us for contribution (e.g., comments, questions, or answers) during Zoom sessions | 4.33 | 0.795 | |

| 3. The instructor paid close attention to us during Zoom sessions | 4.20 | 0.779 | |

| 4. The instructor cared about us during Zoom sessions | 4.31 | 0.767 | |

| 5. The instructor closely monitored our understanding during Zoom sessions | 4.13 | 0.818 | |

| 6. The instructor addressed our concerns and/or questions promptly during Zoom sessions | 4.47 | 0.690 | |

| 7. The instructor ignored us during Zoom sessions | 1.44* | 0.958 | |

| Learners | 8. I was often multi-tasking (e.g., doing something else) during Zoom sessions | 2.93* | 1.152 |

| 9. I closely followed the instructor's presentations during Zoom sessions | 4.18 | 0.696 | |

| 10. I stayed focused during Zoom sessions | 3.78 | 0.786 | |

| 11. I had opportunities to ask the instructor questions during Zoom sessions | 4.35 | 0.775 | |

| 12. I frequently interacted with the instructor during Zoom sessions | 3.62 | 0.892 | |

| 13. I actively interacted with peers during discussions in breakout rooms | 4.44 | 0.660 | |

| 14. I frequently used backchannels (e.g., text chat, WhatsApp) to keep in contact with classmates during Zoom sessions | 3.64 | 1.112 | |

| 15. I had opportunities to take active or leadership roles (e.g., a facilitator or presenter) during Zoom sessions | 3.69 | 1.016 | |

| 16. I actively answered the instructor’s questions during Zoom sessions | 3.76 | 0.769 | |

| 17. I felt socially connected with my classmates in Zoom sessions | 3.40 | 0.974 | |

| 18. I felt socially connected with the instructor in Zoom sessions | 3.55 | 0.919 | |

| 19. I was highly engaged in the Zoom sessions | 3.73 | 0.827 | |

| 20. The Zoom sessions were as engaging as f2f sessions | 3.24 | 1.138 | |

| 21. I would choose the Zoom session rather than f2f if I have a choice | 3.45 | 1.331 | |

| Content | 22. The learning tasks in the course were challenging | 3.65 | 0.947 |

| 23. During a Zoom session, my time-on-task was higher than 80% of the session | 3.38 | 0.972 | |

| 24. The learning activities were interactive in the Zoom sessions | 3.89 | 0.737 | |

| 25. The instructor frequently used online quizzes or polls (e.g., Kahoot) to check our understanding | 3.67 | 0.818 | |

| 26. The online quizzes or polls (e.g., Kahoot) made me focused | 4.22 | 0.686 | |

| 27. I had opportunities to discuss with peers (e.g., in breakout rooms) | 4.33 | 0.668 | |

| 28. I contributed new ideas (e.g., via peer feedback) to the group/class discussions | 4.02 | 0.680 | |

| 29. Group discussion and presentation made me engaged | 4.29 | 0.599 | |

| 30. I actively participate in the class activities in Zoom sessions | 4.09 | 0.800 | |

| Technology | 31. The Zoom tool enabled me to easily follow class instruction | 4.18 | 0.669 |

| 32. The Zoom tool enabled me to easily communicate with the instructor | 4.15 | 0.848 | |

| 33. The Zoom tool enabled me to easily interact with online peers | 4.18 | 0.945 | |

| 34. I encountered some critical technical problems during Zoom sessions | 1.91* | 1.076 | |

| 35. The technology did not cause any disruption for me | 4.04 | 1.036 | |

| Environments | 36. I had adequate infrastructure and equipment to join Zoom sessions from home | 4.44 | 0.811 |

| 37. My home environment was conducive to participating in Zoom sessions | 4.11 | 0.936 | |

| 38. I concentrated on learning when I attended Zoom sessions from home | 3.71 | 0.875 |

* Negatively stated item

Fig. 2.

The illustration of mean scores

Fig. 3.

The number of codes derived from the open-ended question

Instructor factor

Regarding the factor of instructors, the learners perceived highly that the instructors did attempt to engage them in the courses. More specifically, the instructors created warm climates (#1, M = 4.27, SD = 0.781) and cared about them during the online sessions (#4, M = 4.31, SD = 0.767). The instructors also frequently invited them for questions (#2, M = 4.33, SD = 0.795) and addressed their concerns and questions promptly (#6, M = 4.47, SD = 0.69). The instructors were reported to monitor them closely (#5, M = 4.13, SD = 0.818), and the learners did not feel ignored in the learning process (#7, M = 1.44*, SD = 0.958).

There were ten codes derived from the open-ended question regarding instructors. Learners commonly suggested that there should be a balance between lectures and learning activities. They expected to have shorter lectures, more activities, and a frequent switch between lectures and activities. For instance, a learner mentioned that “Keep the zoom sessions shorter. Maybe use a flipped classroom or blended learning approach to keep the zoom sessions shorter”, and another learner wrote “…switching between activities helps… I feel a focused and short task following a short lecture will enable me to listen to the lecture and then apply…”. In addition, they expected to have more breaks by saying “Fatigue could set in during long zoom sessions. Ideally short breaks would help learners to refresh and engage in the sessions better”.

Learner factor

Regarding the factor of learners, results show that they followed the instructors’ presentations closely (#9, M = 4.18, SD = 0.696). But their interaction with the instructors (#12, M = 3.62, SD = 0.892) or the degree of actively answering questions (#16, M = 3.76, SD = 0.769) could be further increased although they had opportunities to do so (#11, M = 4.35, SD = 0.775). Comparatively, they had more interactions with peers (#13, M = 4.44, SD = 0.660). But the interactions mainly occurred during group discussions, and they sometimes used other backchannels like text chat to communicate (#14, M = 3.64, SD = 1.112). Nevertheless, they slightly agreed that they were socially connected with the instructors (#18, M = 3.55, SD = 0.919) and peers (#17, M = 3.40, SD = 0.974). Though the learners felt engaged in the learning process, their engagement level could be further increased (#19, M = 3.73, SD = 0.827). In addition, they slightly agreed that SOL was as engaging as face-to-face (#20, M = 3.24, SD = 1.138). Despite this, they had a slight preference for synchronous learning over face-to-face if they had a choice (#21, M = 3.45, SD = 1.331). They also exercised self-regulation and stayed focused in the learning process as indicated in items #8 and #10.

There were 13 codes derived from the open-ended question with respect to learners. The codes provided an insight into why they preferred synchronous learning or other modes. For instance, one learner who preferred SOL wrote “Zoom sessions offer working adults the flexibility to balance between study and other commitments”, while another learner who preferred face-to-face learning indicated “I would still prefer f2f classes. For zoom sessions, participants switching on cameras and more group activities may improve engagement”. Another learner thought that asynchronous online learning was better as it “gives us time to absorb many new theories and resources”. An additional learner suggested using blended learning said “It is good to have both zoom and physical lessons for effective engagement.”

Some learners elaborated on the importance of motivation and self-regulation. One learner said that “…it is indeed hard to engage adult learners unless they want to be engaged”, and another learner wrote “I would see it as the learners taking ownership of their learning hence taking the initiative to stay engaged… it's mainly a matter of integrity that learners stay engaged”. Yet another mentioned that they should be given more autonomy, saying that “Other than getting the learners to speak up during zoom sessions, include activities for learners who are less comfortable speaking up”.

Content factor

Concerning the factor of learning content, the learners slightly agreed that the learning tasks were generally challenging (#22, M = 3.65, SD = 0.947), and they felt their time-on-task was high but could be increased (#23, M = 3.38, SD = 0.972). They actively participated in class activities (#30, M = 4.09, SD = 0.800) though the activities could be more interactive (#24, M = 3.89, SD = 0.737). They had opportunities to discuss with peers (#27, M = 4.33, SD = 0.668) and felt group discussions engaging (#29, M = 4.29, SD = 0.599). They also actively contributed to group discussions (#28, M = 4.02, SD = 0.680). In addition, online polls made them engaged (#26, M = 4.22 SD = 0.686) but could be more frequently used (#25, M = 3.67, SD = 0.818).

There were 20 codes derived from the open-ended question for learning content. The codes further confirmed that learners were highly engaged in group discussions. However, they sometimes felt neglected in the breakout rooms as the instructor was not always there. For instance, some learners mentioned “… having more group discussions or group tasks made me more deeply engaged with the zoom session”, “Group discussions are engaging, maybe consider inter-group discussions”, and “…at times zoom learners get neglected especially in break out rooms.” In addition, some learners liked individual activities. For instance, one learner said that “Rather I would prefer individual activities that I can complete at my own pace”, and another learner suggested that “There can be a balance between group discussions in breakout rooms and individual tasks/milestone checks such as quizzes”.

For other learners, they agreed that interactive activities like quizzes or polls engaged them. A learner indicated that “I enjoyed zoom sessions. Zoom sessions create a good avenue to engage learners with games and quizzes”. Another learner suggested including “more interactive elements during a presentation. For instance, create activities for learners to annotate on the screen to complete a task or share the ideas”. Furthermore, learners appreciated instructors’ effort to link theory to practice and expected to see more applications or examples as indicated in the quotes: “(I) love how the facilitator provided application aspect to the course, (it) would be great if we could explore more applications”, and “It would have been great if I could see theories … being applied in the design of this module”.

Technology factor

With respect to the factor of technology, results indicated that Zoom enabled the learners to easily follow online lectures (#31, M = 4.18, SD = 0.669), and communicate with instructors (#32, M = 4.15, SD = 0.848) and peers (#33, M = 4.18, SD = 0.945). Technology did not cause them much disruption (#35, M = 4.04, SD = 0.1.036), and they did not encounter critical technical problems in the learning process (#34, M = 1.91*, SD = 1.076).

There were five codes derived from the open-ended question for technology. It seemed that letting learners keep cameras on during lectures and group discussions helped to engage them. This was reflected in quotes such as “To improve the engagement, I suggest the learners to turn on their cameras. It (is) like a virtual attendance”, and “social interactions between peers can be further enhanced by turning on cameras during a breakout session”. Learners also mentioned text chat was a useful feature as it enabled them to ask questions quietly and obtained feedback promptly from others. Supporting this was two learners, who said “Lecturer did improve with feedback to check on our zoom chat as we asked questions and peers shared/answered”, and “(a zoom session) assisted me an introvert to engage in the small group discussion and post on chat”.

Environment factor

For the factor of environments, the learners had adequate infrastructure and equipment (#36, M = 4.44, SD = 0.811), and their home environments were conducive to online learning (#37, M = 4.11, SD = 0.936). Their concentration level was high but could be increased (#38, M = 3.71, SD = 0.875).

There was only one code derived from the open-ended question related to environments, which confirmed that the learners did not have noticeable issues in participating in SOL from home except for one who said that “I experienced hardware issues during zoom sessions and could not sometimes be as active as should”.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore how learners could be engaged in SOL and to identify their perceptions of the engagement strategies applied. This section will discuss the engagement factors, useful strategies, and implications for practitioners as well as limitations and suggestions for future research.

Engagement factors

Technology and environments were perceived to be less critical than the other factors in this study. This finding is inconsistent with the outcomes of other studies showing that technology heavily influences learners’ concentration and engagement (e.g., Cloonan & Hayden, 2018; Divanoglou et al., 2018), and that the lack of infrastructure or distractions from the home environment affects learners’ engagement during home-based learning (Cavinato et al., 2021; Khlaif et al., 2021). There might be a few reasons contributing to the different findings. First, the instructors and learners in this study were quite used to SOL and proficient in handling its processes. Second, the participants were adult learners who might use better equipment and have self-regulation skills. Third, the study was conducted in an economically more developed country where the infrastructure was well in place. However, other studies conducted in the same context before the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., Wang & Huang, 2018) or during the initial stage of the pandemic (e.g., Tay et al., 2021) had a different view. They found that sharing devices with siblings and low Internet connection did negatively affect learners’ engagement. It seems that technology has probably become more mature over the years and learners have become more competent in learning from home. As such, instructors, learners, and content remain as core factors for engaging online learners (Chiu, 2021; Meyer, 2014; Wdowik, 2014).

Engagement strategies and implications

Related to the core factors, this study further identified the following strategies to be highly useful for engaging learners:

-

i)

Interaction with instructors

-

ii)

Interaction with peers

-

iii)

Relevant content and interactive activities

-

iv)

Social connectedness

This study showed that instant interaction with instructors helped engage learners, as learners could follow live lectures simultaneously and receive prompt responses. This finding is consistent with other studies like Heilporn and Lakhal (2021), Morrison (2021), and Kurt et al. (2022) who identified that the instructors’ presence and immediacy in SOL fostered learners’ engagement. However, this study also identified that the learners did not often spontaneously interact with the instructors. This finding concurred with what other studies have found that learners often fail to find a proper time to ask questions (e.g., Wang, Huang & Quek, 2017). To foster more learner-instructor interaction, instructors must have remote lecturing skills like talking to the webcam, pausing for a while during a lecture, or inviting silent learners by calling their names, as suggested by Lakhal et al., (2020).

This study also revealed that having frequent interactions with peers increased learners’ engagement. This finding supports the notion that learner-learner interaction has a strong predictive capacity for learner engagement (Wdowik, 2014). However, the study also found that learners felt neglected during group discussions in breakout rooms. Other studies have also reported additional challenges faced by instructors when they navigate through different breakout rooms (Ranga, 2020) or distribute worksheets to learners in breakout rooms (Cavinato et al., 2021). The findings suggest that instructors must have competency in facilitating synchronous online discussions.

This study also found that relevant content to learners’ practice and interactive activities helped engage learners. This finding supports existing studies which claim that course resources must cater to learning needs and preferences (Hew, 2018) and enable learners to apply them to practice (Bolliger & Martin, 2018). To engage learners, this study further implies that learning activities preferably include both individual (e.g., online polls, annotating on the same document) and group work (e.g., discussions and peer feedback), and there should also be a balance between instructor-led lectures and learner-centred activities.

Furthermore, this study displayed that SOL allowed the instructors to connect with the learners and build social connectedness with them. Other studies like Chiu (2021); Kurt et al. (2022) have similar findings. However, additional research indicates that SOL is less helpful for individuals to establish a close relationship with the instructor as informal conversations are unlikely to occur in an open meeting room for the whole class (Ranga, 2020). Nevertheless, this study demonstrated that providing informal conversation opportunities like creating additional breakout rooms for individual learners to informally talk to the instructors helped to create a close learner-instructor relationship. This result implies that instructors may use strategies like creating additional breakout rooms or talking to them informally before the start of a session to increase social connectedness with learners.

In summary, the first three strategies are closely related to the interactions (i.e., learner-instructor, learner-learner, and learner-content) proposed by Moore (1989). These interactions have been regularly applied in both classroom and online learning environments to engage students. Comparatively, the last strategy, which is related to emotional engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004), is relatively newer and less studied than behavioural and cognitive engagement in existing studies (Bedenlier et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). However, social connectedness between learners and instructors is crucial as learners can easily feel isolated in an online learning environment due to the geographical separation from others (Chiu, 2021; Ruzek et al., 2016). Thus, more research and practice are needed in this area to enhance learner-instructor relationships.

Limitations and future research

This study had a few limitations. It was conducted in an economically more developed country with adult learners as participants. The findings therefore may not apply to other contexts. In addition, the findings were derived from the learners’ perceptions in a survey, and using a survey is retrospective and the responses are subjective (Henrie et al., 2015). Future research can explore the possibility of using facial detection tools to automatically track learners’ engagement in the ongoing process. Additional research can also investigate how instructors effectively facilitate synchronous online discussions, though asynchronous online discussion has been well studied in the literature (Cheung et al., 2008). Moreover, future research can examine how to foster social connectedness between learners and instructors as mentioned above.

Conclusion

This study shows that instructors, learners, and content are the core factors that highly affect learner engagement. Comparatively, technology and physical environments become less important. More specifically, this study identifies that frequently interacting with instructors and peers, involving relevant learning content that relates to practice, having interactive learning activities, and establishing social connectedness between instructors and learners, are useful strategies that can help to engage learners. But there are still other challenges as revealed in this study. Future studies can explore how to facilitate synchronous online discussions, establish a social rapport with individual learners, and use technology to automatically monitor learners’ engagement in the learning process.

Authors’ contributions

QW taught two classes, conduct the survey, and wrote the manuscript; YW taught two classes of the study and conducted the survey, and CLQ conducted data analysis. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the MOE education research fund (grant number: OER 11/21WQY), and data collection was approved by the university IRB committee (ref: IRB-2021–196).

Data availability

The collected and analysed data during the current study are available from the corresponding author and will be available online too.

Declarations

Competing interests

There is no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qiyun Wang, Email: qiyun.wang@nie.edu.sg.

Yun Wen, Email: Yun.wen@nie.edu.sg.

Choon Lang Quek, Email: Choonlang.quek@nie.edu.sg.

References

- Angelone, L., Warner, Z., & Zydney, J.M. (2020). Optimizing the technological design of a blended synchronous learning environment. Online Learning, 24(3), 222–240. 10.24059/olj.v24i3.2180

- Appleton J, Christenson S, Kim D, Reschly A. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44(5):427–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JP, Goodboy AK, Bowman ND, Wright AA. Does teaching with PowerPoint increase students’ learning? A meta-analysis. Computers & Education. 2018;126:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter G, Hainey T. Remote learning in the context of COVID-19: Reviewing the effectiveness of synchronous online delivery. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning. 2022 doi: 10.1108/jrit-12-2021-0086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Kerres, M. (2020). Facilitating student engagement through educational technology in higher education: A systematic review in the field of arts and humanities. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 126–150. 10.14742/ajet.5477

- Blakey, C.H., & Major, C.H. (2019). Student perceptions of engagement in online courses: An exploratory study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 22.

- Boelens R, de Wever B, Voet M. Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review. 2017;22:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger DU, Martin F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Education. 2018;39(4):568–583. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1520041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bower M, Dalgarno B, Kennedy GE, Lee M, Kenney J. Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education. 2015;86:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bundrick M, Quaglia R, Corso M, Haywood D. Promoting student engagement in the classroom. Teachers College Record. 2014;116:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder, G. (2017). Emerging evidence regarding the roles of emotional, behavioural, and cognitive aspects of student engagement in the online classroom, School of Psychology Publications, 118.

- Cavinato AG, Hunter RA, Ott LS, Robinson JK. Promoting student interaction, engagement, and success in an online environment. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2021;413(6):1513–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00216-021-03178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung W, Hew K, Ng C. Toward an understanding of why students contribute in asynchronous online discussions. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 2008;38(1):29–50. doi: 10.2190/EC.38.1.b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T. (2021). Student engagement in K-12 online learning amid COVID-19: A qualitative approach from a self-determination theory perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–14. 10.1080/10494820.2021.1926289

- Cho K, Cho MH. Training of self-regulated learning skills on a social network system. Social Psychology of Education. 2013;16(4):617–634. doi: 10.1007/s11218-013-9229-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan, L., & Hayden, I. (2018). A critical evaluation of the integration of a blended learning approach into a multimedia applications module. AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education,10(3). https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/359/606

- Conklin S, Lowenthal P, Trespalacios J. Graduate students' perceptions of interactions in a blended synchronous learning environment: A case study. Quarterly Review of Distance Education. 2019;20(4):45–100. [Google Scholar]

- Conklina S, Oyarzun B, Barreto D. Blended synchronous learning environment: Student perspectives. Research on Education and Media. 2017;9(1):17–23. doi: 10.1515/rem-2017-0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, U. (2014). Teaching the disembodied: Othering and activity systems in a blended synchronous learning situation. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15, 1–9. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1793

- Deschaine, M. E., & Whale, D. E. (2017). Increasing student engagement in online educational leadership courses. Journal of Educators Online, 14(1).

- Deshpande, A., & Chukhlomin, V. (2017). What makes a good MOOC: A field study of factors impacting student motivation to learn. American Journal of Distance Education, 1–19. 10.1080/08923647.2017.1377513

- Divanoglou, A., Chance-Larsen, K., Fleming, J., & Wolfe, M. (2018). Physiotherapy student perspectives on synchronous dual-campus learning and teaching. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3). 10.14742/ajet.3460

- Fabriz S, Mendzheritskaya J, Stehle S. impact of synchronous and asynchronous settings of online teaching and learning in higher education on students’ learning experience during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:733554. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francescucci A, Rohani L. Exclusively synchronous online (viri) learning: The impact on student performance and engagement outcomes. Journal of Marketing Education. 2019;41(1):60–69. doi: 10.1177/0273475318818864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks J, Blumenfeld P, Paris A. School engagement. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74(1):59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisby, B., Sexton, B., Buckner, M., Beck, A., & Kaufmann, R. (2018). Peers and instructors as sources of distraction from a cognitive load perspective. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 12(2).

- Gilmore, A., & Daher, T., & Peteranetz, M. S. (2020, June), A multi-year case study in blended design: student experiences in a blended, synchronous, distance controls course. Paper presented at 2020 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access. 10.18260/1-2--34018

- Guo S. Synchronous versus asynchronous online teaching of physics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physics Education. 2020;55(6):065007. doi: 10.1088/1361-6552/aba1c5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2019). Learner engagement in blended learning environments: a conceptual framework. Online Learning, 23(2). 10.24059/olj.v23i2.1481

- Heilporn G, Lakhal S. Converting a graduate-level course into a HyFlex modality: What are effective engagement strategies? The International Journal of Management Education. 2021;19(1):100454. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heilporn, G., Lakhal, S., & Bélisle, M. (2021). An examination of teachers’ strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(25), 10.1186/s41239-021-00260-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Henrie CR, Halverson LR, Graham CR. Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers & Education. 2015;90:36–53. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, T. C. (2003). Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 19(1), 59–71. 10.14742/ajet.1701

- Hew KF. Unpacking the strategies of ten highly rated MOOCs: Implications for engaging students in large online courses. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education. 2018;120(1):1–40. doi: 10.1177/016146811812000107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes N. Engaging with assessment: Increasing student engagement through continuous assessment. Active Learning in Higher Education. 2018;19(1):23–34. doi: 10.1177/1469787417723230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kee CE. The impact of COVID-19: Graduate students’ emotional and psychological experiences. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2021;31(1–4):476–488. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2020.1855285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J. Motivation design of instruction. In: Reigeluth C, editor. Instructional Design Theories and Models: An Overview of Their Current Status. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. pp. 383–434. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif ZN, Salha S, Kouraichi B. Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Education and Information Technologies. 2021;26(6):7033–7055. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt G, Atay D, Öztürk HA. Student engagement in K12 online education during the pandemic: The case of Turkey. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. 2022;54(sup1):S31–S47. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2021.1920518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum, B. (2020). Examining students’ confidence to learn online, self-regulation skills and perceptions of satisfaction and usefulness of online classes. Online Learning, 24(3), 128- 146. 10.24059/olj.v24i3.2066

- Lakhal, S., Mukamurera, J., Bédard, M. E., Heilporn, G., & Chauret, M. (2020). Features fostering academic and social integration in blended synchronous courses in graduate programs. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1). 10.1186/s41239-020-0180-z

- Lee, J., Sanders, T., Antczak, D., Parker, R., Noetel, M., Parker, P., & Lonsdale, C. (2021). Influences on user engagement in online professional learning: A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 003465432199791. 10.3102/0034654321997918

- Li, X., Yang, Y., Chu, K., Zainuddin, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Applying blended synchronous teaching and learning for flexible learning in higher education: An action research study at a university in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. 10.1080/02188791.2020.1766417

- Liu W, Mei J, Tian L, Huebner ES. Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-being in school among students. Social Indicators Research. 2016;125(3):1065–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-0873-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manwaring K, Larsen R, Graham C, Henrie C, Halverson L. Investigating student engagement in blended learning settings using experience sampling and structural equation modeling. The Internet and Higher Education. 2017;35:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Budhrani K, Kumar S, Ritzhaupt A. Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Roles and competencies. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks JALN. 2019;23(1):184. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, J. A. (2021). From classroom to Zoom room: Exploring instructor modifications of visual nonverbal behaviors in synchronous online classrooms. Communication Teacher, 1–12. 10.1080/17404622.2021.1981959

- Meyer KA. Student engagement in online learning: What works and why. ASHE Higher Education Report. 2014;40(6):1–114. doi: 10.1002/aehe.20018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomerie K, Edwards M, Thorn K. Factors influencing online learning in an organisational context. The Journal of Management Development. 2016;35(10):1313–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–7. http://aris.teluq.uquebec.ca/portals/598/t3_moore1989.pdf

- Morrison JS. Getting to know you: Student-faculty interaction and student engagement in online courses. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice. 2021;21(12):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Olt PA. Virtually there: Distant freshmen blended in classes through synchronous online education. Innovative Higher Education. 2018;43(5):381–395. doi: 10.1007/s10755-018-9437-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Bonk CJ. Synchronous learning experiences: Distance and residential learners’ perspectives in a blended graduate course. Journal of Interactive Online Learning. 2007;6(3):245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Pentaraki A, Burkholder G. Emerging evidence regarding the roles of emotional, behavioural, and cognitive aspects of student engagement in the online classroom. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning. 2017;20(1):1–21. doi: 10.1515/eurodl-2017-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pittaway, S. M. (2012). Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a faculty of education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4). 10.14221/ajte.2012v37n4.8

- Raes A, Vanneste P, Pieters M, Windey I, van den Noortgate W, Depaepe F. Learning and instruction in the hybrid virtual classroom: An investigation of students’ engagement and the effect of quizzes. Computers & Education. 2020;143:103682. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey D, Evans J, Levy M. Preserving the seminar experience. Journal of Political Science Education. 2016;12(3):256–267. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2015.1077713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranga J. Online Engagement of commuter students in a general chemistry course during COVID-19. Journal of Chemical Education. 2020;97(9):2866–2870. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rautanen P, Soini T, Pietarinen J, Pyhältö K. Primary school students’ perceived social support in relation to study engagement. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10212-020-00492-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Hall E, Vicentini C. Examining distance learners in hybrid synchronous instruction: Successes and challenges. Online Learning. 2017;21(4):141–157. doi: 10.24059/olj.v21i4.1258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek E, Hafen C, Allen J, Gregory A, Mikami A, Pianta R. How teacher emotional support motivates students: The mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learning and Instruction. 2016;42:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R, Deci E. Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad N, Sankaran S. Technology proficiency in teaching and facilitating. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Education. 2020 doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan D. Transitioning from face-to-face to remote learning: Students’ attitudes and perceptions of using Zoom during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science (IJTES) 2020;4(4):335–342. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano D, Dea-Ayuela M, Gonzalez-Burgos E, Serrano-Gil A, Lalatsa A. Technology-enhanced learning in higher education: How to enhance student engagement through blended learning. European Journal of Education. 2019;54(2):273–286. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tait A. Planning student support for open and distance learning. Open Learning. 2000;15(3):287–299. doi: 10.1080/713688410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay L, Lee S, Ramachandran K. Implementation of online home-based learning and students’ engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Singapore mathematics teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 2021;30(3):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00572-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas, L., Lasen, M., Field, E., & Skamp, K. (2015). Promoting online students’ engagement and learning in science and sustainability preservice teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(11). 10.14221/ajte.2015v40n11.5

- Tuckman, B. W. (1999). Conducting educational research (5th ed.). Thomson Learning.

- UTSA (2020). Teaching and learning in the time of Covid-19, Research Brief: Student engagement and learning, Urban Education Institute at UTSA. https://uei.utsa.edu/_files/pdfs/DistanceLearningBrief2-8-17-20.pdf

- Vale, J., Oliver, M., & Clemmer, R. M. C. (2020). The influence of attendance, communication, and distractions on the student learning experience using blended synchronous learning. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(2). 10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.2.11105

- Wang Q, Huang C. Pedagogical, social and technical designs of a blended synchronous learning environment. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2018;49(3):451–462. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q., Huang, C., & Quek, C. (2017). Students’ perspectives on the design and implementation of a blended synchronous learning environment. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34 (1), 1–13. 10.14742/ajet.3404

- Warren, T. (2020). Zoom faces a privacy and security backlash as it surges in popularity, The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/1/21202584/zoom-security-privacy-issues-video-conferencing-software-coronavirus-demand-response

- Wdowik S. Using a synchronous online learning environment to promote and enhance transactional engagement beyond the classroom. Campus-Wide Information Systems. 2014;31(4):264–275. doi: 10.1108/cwis-10-2013-0057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zydney JM, McKinney P, Lindberg R, Schmidt M. Here or there instruction: Lessons learned in implementing innovative approaches to blended synchronous learning. TechTrends. 2019;62(2):123–132. doi: 10.1007/s11528-018-0344-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The collected and analysed data during the current study are available from the corresponding author and will be available online too.