Abstract

Three serial isolates of Candida albicans were obtained by direct swab or by oral saline rinses from each of five human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis. Genotyping techniques confirmed the presence of a persistent strain in multiple episodes from the same patient, which was different from the strains isolated from other patients. Fluconazole susceptibility was determined by both an agar dilution method and the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards macrobroth procedure. In four of these patients the strains developed fluconazole resistance, and in one patient the strain remained susceptible. The different isolates were propagated as yeast cells on a synthetic medium, and their cell wall proteinaceous components were extracted by treatment with β-mercaptoethanol. Protein and mannoprotein components present in the extracts were analyzed by electrophoresis, immunoblotting, and lectin-blotting techniques. The analysis showed a similar composition, with only minor qualitative and quantitative differences in the polypeptidic and antigenic patterns associated with the cell wall extracts from serial isolates from the same patient, as well as those from different strains isolated from different patients. Use of monospecific antibodies generated against two immunodominant antigens during candidiasis (enolase and the 58-kDa fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein) demonstrated their expression in all isolates tested. Overall, the antigenic makeup of C. albicans strains remained constant during the course of infection and was not affected by development of fluconazole resistance. In contrast to previous reports, the low degree of antigenic variability observed in this study may be due to the fact that the isolates were obtained from a highly homogeneous population of patients and to the uniformity in techniques used for the isolation, storage, and culture of the different strains, as well as extraction methodologies.

Although the cell wall of Candida albicans was previously considered an almost inert structure, today its importance is well established in almost every aspect of the biology and pathogenicity of this fungus (10, 11). The cell wall of C. albicans is a complex mosaic of polysaccharides and proteins in which mannoproteins constitute the major antigens and host recognition molecules. A number of studies from different laboratories have demonstrated a high degree of complexity associated with the protein and mannoprotein composition of the cell wall of C. albicans (reviewed in reference 11). Also, the expression, chemical characteristics, and physiological properties of proteins and mannoproteins present in the C. albicans cell wall appear to be dependent on multiple environmental (i.e., growing conditions, nutritional factors, temperature) as well as organism (strain, morphology, phenotypic switching)-related factors (1, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 16, 18, 26, 30, 40–42, 49, 50). Thus, the C. albicans cell wall appears to be a highly dynamic structure that exhibits the ability to differentially express constituents useful for switching between commensal and pathogenic lifestyles and for modulating and/or evading immune host defenses (12, 32).

Cell wall proteins and mannoproteins of C. albicans are major elicitors of the host immune response, and our increasing knowledge of the identity and expression of these components may assist in the development of novel approaches for the management of the different forms of candidiasis (32, 33). Characterization of cell wall antigens and anti-cell wall antibodies may provide the basis for developing improved methods for the serodiagnosis of candidiasis (21, 32, 43). In addition, in recent years, there has been increasing evidence that some Candida-specific antibodies can be immunoprotective during infection, at both the mucosal and the systemic levels, thus suggesting the viability of an immunotherapy and/or vaccine approach for the treatment and management of candidiasis (7, 17, 33, 35). In the present study, in which extrinsic variables were minimized, we present evidence for low levels of antigenic variability associated with cell wall antigens of C. albicans clinical isolates obtained during successive episodes of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients, including isolates that developed resistance to fluconazole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

Three serial isolates of C. albicans were obtained by direct swab or by oral saline rinses from five HIV-infected patients with recurrent OPC enrolled in a longitudinal study to assess significance of fluconazole resistance. Patients were treated initially with fluconazole at 100 mg/day and increased doses up to 800 mg/day if necessary for clinical resolution if development of resistance was detected (44). The identity of the clinical isolates as C. albicans was confirmed by both biochemical (API 20C; Analytab Products) and microbiological (germ tube formation in serum-containing medium and color in CHROMagar Candida) procedures. Initial plating of isolates and preliminary assessment of drug susceptibility were performed by a fluconazole agar dilution method (37, 38). Briefly, dilutions of oral samples are added to plates containing solid medium with or without fluconazole, and individual colonies are then recovered. This technique maximizes early detection of resistant isolates (37, 38). Fluconazole MICs for the different isolates were determined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) broth macrodilution procedure (36). The different isolates were stored at room temperature as suspensions in sterile deionized water. Table 1 lists the isolates, the patients from which they were recovered, the elapsed time of isolation, and the fluconazole MICs for the isolates.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans isolates from patients with OPC

| Isolate | No. of days since first isolation | Fluconazole MICa (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient A | ||

| 1 | 4 | |

| 2 | 20 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 138 | 4 |

| Patient B | ||

| 4 | 0.5 | |

| 5 | 210 | 8 |

| 6 | 280 | >64 |

| Patient C | ||

| 7 | 4 | |

| 8 | 7 | 16 |

| 9 | 296 | 32 |

| Patient D | ||

| 10 | 0.5 | |

| 11 | 15 | 8 |

| 12 | 58 | 16 |

| Patient E | ||

| 13 | 0.25 | |

| 14 | 44 | 8 |

| 15 | 100 | 16 |

Determined by the NCCLS broth macrodilution method.

Strain identification.

Strain identity was investigated by karyotyping, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and DNA fingerprinting using the moderately repetitive probe Ca3 as previously described (28). Briefly, chromosomes from the different isolates were prepared in agarose plugs, separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light. RFLP patterns were generated by digestion of genomic DNA with SfiI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). After separation by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed. Following documentation, the materials present in the RFLP gels were transferred to nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.) and hybridized with a Ca3 probe radioactively labeled by random priming (Random Primers DNA Labeling System; GibcoBRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The membranes were then washed and exposed to autoradiography film (Du Pont, Wilmington, Del.). Pictures of the gels or films were scanned by using the Adobe Photoshop program (Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, Calif.). For preparation of figures, digital images were processed with the Adobe Photoshop program.

Preparation of cell wall extracts.

The different isolates were subcultured onto plates containing Sabouraud dextrose agar 48 h prior to propagation as blastoconidia (yeast phase) in the minimal medium supplemented with amino acids described by Lee and colleagues (24), for which a loopful of cells from the corresponding plate were inoculated into a flask containing the liquid medium, and incubated for 24 h at room temperature in an orbital shaker. β-Mercaptoethanol (βME) was used to solubilize protein and glycoprotein components from the walls of intact C. albicans cells as previously described with minor modifications (27). Briefly, cells from cultures of each isolate were independently resuspended in alkaline buffer containing 1% (vol/vol) βME and incubated for 45 min at 37°C with gentle agitation. After treatment, the cells were sedimented, and the supernatant fluid was recovered and centrifuged in a Millipore Ultrafree-15 centrifugal filter device (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) for desalting and concentration (βME extract). The total sugar contents in the different samples were determined colorimetrically with mannose as a standard (14).

PAGE and Western blot.

Cell wall components present in the βME extracts from the different isolates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using precast 4 to 15% acrylamide gradient minigels (Bio-Rad). Coomassie staining of the proteins present in the gels, electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, and indirect staining of glycoproteins present in the membranes with concanavalin A were performed as previously described (8). Different antibody preparations were used as probes for immunoblotting experiments: (i) a pooled polyclonal antiserum generated against Zymolyase and βME cell wall extracts from C. albicans 3153A (27), (ii) a polyclonal antibody preparation generated against the purified 58-kDa fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein (mp58) of C. albicans (9), (iii) a monospecific polyclonal antiserum generated against recombinant C. albicans enolase expressed as a 6-histidine-tagged protein in Escherichia coli (to be described elsewhere), (iv) pooled serum samples from the same HIV-infected patients with OPC from whom the strains were isolated, and (v) fresh pooled oral saline rinses obtained from patients enrolled in the study (the saline washes were centrifuged at low speed prior to their utilization in the assay). The different antibody preparations were diluted in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer saline (pH 7.4), supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% bovine serum albumin (TBSTB buffer). Anti-rabbit (immunoglobulin G [IgG]), anti-mouse (IgG), or anti-human (IgG, IgM, and IgA) peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (depending on the antibody preparation used during the primary incubation) were used as indicator antibodies, with 4-chloro-1-naphthol as chromogenic reagent. The gels or blots were scanned by using the Adobe Photoshop program. For preparation of figures, digital images were processed by using the Adobe Photoshop program.

RESULTS

Genotyping of isolates.

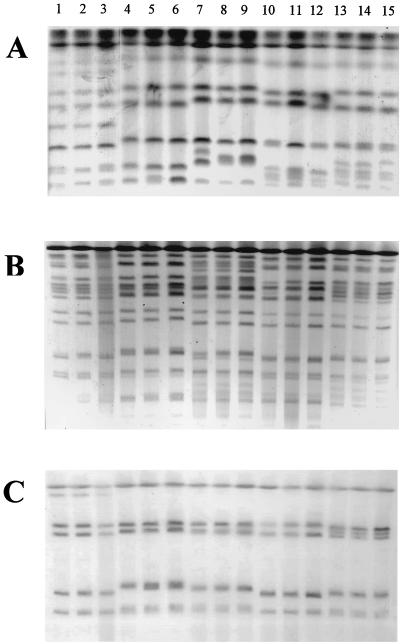

The identities of strains from a given patient were confirmed by karyotyping, RFLP, and fingerprinting with the C. albicans Ca3 probe (Fig. 1). Sequential isolates from each patient were demonstrated to be highly related and distinct from isolates recovered from other patients by all typing methods employed (Table 1). Minor differences in the karyotyping patterns between isolates 7 to 9 (from patient C) are suggestive of the fact that these isolates may constitute different substrains or strain variants of the same persistent strain rather than a completely unrelated strain. These results indicated presence of a persistent strain in each different patient that was associated with the initial episode and successive relapses. They also indicated that the serial isolates from a given patient included in the present study are genotypically similar.

FIG. 1.

Karyotype (A), RFLP analysis generated by SfiI digestion of genomic DNA (B), and fingerprinting analysis with the Ca3 probe (C) of C. albicans clinical isolates recovered during three OPC episodes from HIV-infected patients. See Table 1 for identities of isolates.

Analysis of βME cell wall extracts from different isolates.

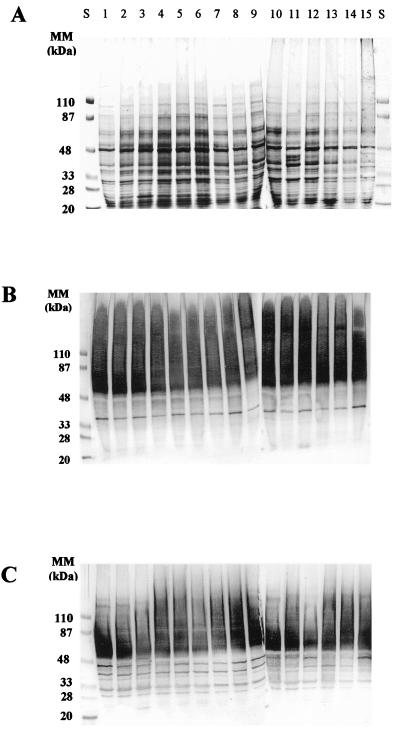

For all the C. albicans isolates included in the analysis, treatment of intact cells with βME led to the solubilization of a complex array of cell wall proteinaceous components, exhibiting a wide range of apparent molecular masses (from >200 to <20 kDa) when separated by SDS-PAGE. Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2A) allowed detection of the medium- to low (<120-kDa)-molecular-mass proteins present in the different extracts and revealed no major differences in the peptidic profiles associated with the βME extracts obtained from the different C. albicans isolates, independently of the patient from whom they were initially isolated. In all cases, the high-molecular-mass material (>120 kDa) was insensitive to the dye, as has been reported previously (8). Indirect concanavalin A-peroxidase staining of the nitrocellulose blots revealed the glyco(manno)protein nature of the high-molecular-weight materials (HMWM) present in cell wall extracts from all isolates (Fig. 2B). Staining with the lectin resulted in poorly resolved patterns due to the highly glycosylated and polydisperse nature of the HMWM. The lectin also recognized a discrete band showing an apparent electrophoretic mobility of approximately 35 kDa present in all isolates tested. Once again, no major differences between the different isolates were detected by the lectin blot technique. A similar antigenic composition associated with the cell wall extracts from the various C. albicans isolates was further revealed by immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal antiserum generated against a collection strain of C. albicans, which recognizes most of the moieties present in the extract (27). This polyclonal antiserum recognized antigenic components along the whole spectrum of molecular masses of species present on the blots. Reactivity included both polydisperse bands mainly in the HMWM and discrete moieties present in the medium- to low-molecular-mass range (Fig. 2C). These included discrete bands exhibiting electrophoretic mobilities of approximately 29, 32, 35, 39, 45, and 48 kDa, together with highly reactive components of apparent molecular masses between 55 and 80 kDa.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoretic profiles of total proteinaceous components present in βME extracts from C. albicans clinical isolates. The materials present in the extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue (A) or subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and reacted with concanavalin A-peroxidase (B) or with a pooled polyclonal antiserum preparation (diluted 1:2,000 in TBSTB) generated against cell wall components of the C. albicans type strain 3153A (C). The amount applied to each well was 50 μg (A and C) or 25 μg (B) of material, expressed as total sugar content. Lanes S, standard proteins of known molecular masses (MM) run in parallel.

Presence of immunodominant C. albicans enolase and mp58 in the cell wall extracts of C. albicans isolates.

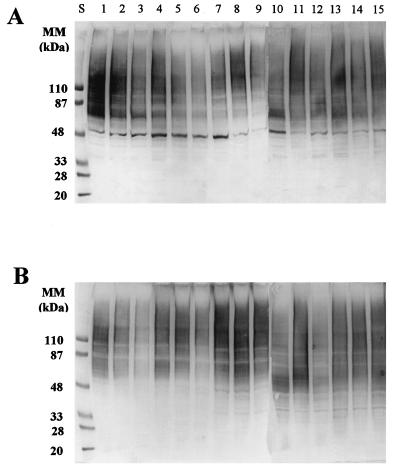

Immunoblot analysis of βME extracts from all isolates tested with monospecific antibodies generated against recombinant C. albicans enolase and the purified 58-kDa fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein (mp58) confirmed the presence of these two highly immunogenic moieties in the cell wall extracts from all isolates examined (Fig. 3). As expected, in the case of the fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein, the polyclonal antibody preparation recognized a homologous broad band displaying an apparent molecular mass of approximately 58 kDa in all isolates tested (Fig. 3A). When a monospecific antibody generated against recombinant C. albicans enolase was used as a probe in the immunoblots (Fig. 3B), strong reactivity was detected with a 48-kDa discrete band present in the extracts from all C. albicans isolates tested.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antiserum (diluted 1:500 in TBSTB) generated against the purified C. albicans mp58 (A) and a monospecific polyclonal antiserum (diluted 1:250 in TBSTB) against recombinant C. albicans enolase (B). Materials present in the extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (A) or anti-mouse IgG (B) (diluted 1:2,000 in TBSTB) were used as indicator antibodies. The amount applied to each well was 50 μg of material, expressed as total sugar content. Molecular masses (MM) of prestained standard proteins run in parallel (lanes S) are indicated.

Presence of antibodies against cell wall proteins in serum samples and oral saline rinses from HIV-infected patients with OPC.

Anti-Candida antibodies are present in the sera from normal and infected individuals. A local antibody response, mainly secretion of IgA, is also induced at the mucosal level during episodes of OPC (reviewed in reference 32). Thus, serum samples and oral saline rinses from patients with OPC provided additional antibody preparations for the study of cell wall antigenic composition associated with the different C. albicans isolates. Antibodies present in serum samples (Fig. 4A) recognized the polydisperse HMWM (as expected, since antimannan antibodies are ubiquitous in human sera) (32), as well as several well-defined medium- to low-molecular-mass bands present in the extracts. A particularly intense labeling was observed in the region of 70 to 90 kDa, which may represent reactivity to a cluster of candidal antigens, which includes heat shock proteins, that are highly immunogenic (23, 25, 34). Also, among other bands, a high level of reactivity was detected against a moiety with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 48 kDa, which may correspond to enolase, as described above. When a preparation consisting of pooled oral saline rinses from patients with OPC was used as a probe in the immunoblots, diffuse reactivity was observed mainly against HMWM (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of the materials present in the βME extracts from the different C. albicans isolates, using as probes pooled serum samples (diluted 1:500 in TBSTB) of the same HIV-infected patients with OPC from whom the strains were isolated (A) or fresh oral saline rinses (diluted 1:10 in TBSTB) from HIV-infected patients with OPC (B). SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes were performed as for Fig. 3. A mixture of peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG, IgM, and IgA (diluted 1:500 each in TBSTB) was used as secondary antiserum. The amount loaded in each well was 50 μg of material, expressed as total sugar content. Lanes S, standard proteins of known molecular masses (MM) run in parallel.

DISCUSSION

Fueled by important observations on the role of antibodies during fungal infections (7, 32), together with the emergence of resistance to the most common antifungal drugs currently used (45), a renewed interest in the development of novel, immune-based strategies for the management of fungal infections, including the different manifestations of candidiasis (7, 32), has developed. These could include both vaccination (as immunoprophylaxis in selected at-risk patients) and immunotherapy (as adjunctive treatment to complement antifungal-drug regimens currently in use). However, the antigenic variability exhibited by C. albicans could severely hamper progress in the development of such novel strategies. Characterization of common immunodominant antigens during candidiasis is essential in identification of new opportunities for immunointervention.

The present study was designed to minimize the effect of extrinsic factors on the proteinaceous and antigenic composition of the C. albicans cell surface. First, the study included serial isolates from successive episodes of OPC that represented the same strain for each of the patients, as determined by a variety of genotyping techniques. Second, we also maintained consistency in the different techniques used for manipulation of the strains, including screening and initial isolation, storage, culture conditions, and extraction methodologies, since all these have been described as affecting antigenic composition (6, 20). Third, we focused on the protein component rather than the carbohydrate component that has been associated with a higher degree of variability (3, 19, 20). In doing so, we were able to demonstrate low levels of antigenic variability among C. albicans isolates and identify proteinaceous antigens that are common to all isolates tested. Enolase and the 58-kDa fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein (mp58) are immunodominant antigens present in the C. albicans cell wall, eliciting potent antibody responses during candidiasis (2, 9, 15, 29, 46–48). The present study confirmed their presence in cell wall extracts from all isolates under investigation and provided confirmation of their immunodominant role. Moreover, the use of serum and oral saline rinses from patients as probes in the immunoblots demonstrated that some of these antigens are able to elicit an antibody response “in vivo” during infection. Interestingly, although preliminary in nature, these experiments also demonstrated a different antibody response to C. albicans cell wall antigens at the mucosal and systemic levels and are indicative of the compartmentalization of the immune response to this pathogen.

The present study combines the use of typing techniques to determine strain identity (genotype) (39) with the analysis of cell wall extracts to assess antigenic variability (phenotype). Despite major genotypic differences detected between isolates recovered from different patients, the “antigenic fingerprints” were similar, and the analysis of cell wall components allowed characterization of antigenic moieties common to all strains tested. Also important is the fact that the antigenic makeup did not appear to change with progression of infection or with development of fluconazole resistance. This is demonstrated by the detection of virtually the same antigenic profiles associated with matched sets of susceptible and resistant isolates obtained in successive OPC episodes from a given patient. It has to be noted that some of these isolates were recovered almost 1 year apart (Table 1). This is in contrast to changes in other phenotypic properties, such as increased levels of expression of efflux pumps or enzymes involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis, detected in the same isolates as resistance developed (28). Since decreased susceptibility to this antifungal agent has been associated with increasing rates of clinical failures (4, 22, 31, 44, 45), it is precisely in these instances that the development of immune-based therapies should prove more important in helping combat refractory disease.

Overall, the present report describes low levels of antigenic variability associated with components present in cell wall extracts obtained from C. albicans clinical isolates, including fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant isolates, propagated as blastospores in a synthetic medium. These results offer new hope for the development of novel management strategies for candidiasis that are urgently needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Pfizer Inc. and by Public Health Service grants 1 R29 AI42401 (to J.L.L.-R.), 5 RO1 DE11381 (to T.F.P.), and M01-RR-01346 for the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center.

Chromogenic medium was provided by CHROMagar Company. We thank the Fungus Testing Laboratory at UTHSCSA for performing antifungal susceptibility testing and Antonio Cassone for helpful comments and suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloush H M, López-Ribot J L, Chaffin W L. Dynamic expression of cell wall proteins of Candida albicans revealed by probes from cDNA clones. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angiolella L, Facchin M, Stringaro A, Maras B, Simonetti N, Cassone A. Identification of a glucan-associated enolase as a main cell wall protein of Candida albicans and an indirect target of lipopeptide antimycotics. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:684–690. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barturen B, Bikandi J, San Millán R, Moragues M D, Régulez P, Quindós G, Pontón J. Variability in expression of antigens responsible for serotype specificity in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1995;141:1535–1543. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boschman C R, Bodnar U R, Tornatore M A, Obias A A, Noskin G A, Englund K, Postelnick M A, Suriano T, Peterson L R. Thirteen-year evolution of azole resistance in yeast isolates and prevalence of resistant strains carried by cancer patients at a large medical center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:734–738. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawner D L, Cutler J E. Variability in expression of cell surface antigens of Candida albicans during morphogenesis. Infect Immun. 1986;51:337–343. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.1.337-343.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brawner D L, Cutler J E, Beatty W L. Caveats in the investigation of form-specific molecules of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1990;58:378–383. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.2.378-383.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadevall A. Antibody immunity and invasive fungal infections. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4211–4218. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4211-4218.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casanova M, Gil M L, Cardeñoso L, Martínez J P, Sentandreu R. Identification of wall-specific antigens synthesized during germ tube formation by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1989;57:262–271. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.262-271.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casanova M, López-Ribot J L, Monteagudo C, Llombart-Bosch A, Sentandreu R, Martínez J P. Identification of a 58-kilodalton cell surface fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein from Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4221–4229. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4221-4229.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassone A. Cell wall of Candida albicans: its functions and its impact on the host. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1989;3:248–314. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3624-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaffin W L, López-Ribot J L, Casanova M, Gozalbo D, Martinez J P. Cell wall proteins of Candida albicans: identity, function, and expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:130–180. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.130-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler J E, Kanbe T. Antigenic variability of Candida albicans cell surface. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1993;5:27–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bernardis F, Molinari A, Boccanera M, Stringaro A, Robert R, Senet J M, Arancia G, Cassone A. Modulation of cell surface associated mannoprotein antigen expression in experimental candidal vaginitis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:509–519. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.509-519.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklyn K M, Warmington J R, Ott A K, Ashman R B. An immunodominant antigen of Candida albicans shows homology to the enzyme enolase. Immunol Cell Biol. 1990;68:173–178. doi: 10.1038/icb.1990.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil M L, Casanova M, Martínez J P, Sentandreu R. Antigenic cell wall mannoproteins in Candida albicans isolates and other Candida species. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1053–1056. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-5-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han Y, Cutler J E. Antibody response that protects against disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2714–2719. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2714-2719.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazen K C, Hazen B W. Hydrophobic surface protein masking by the opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1499–1508. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1499-1508.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernando F L, Cailliez J C, Trinel P A, Faille C, Mackenzie D W R, Poulain D. Qualitative and quantitative differences in recognition patterns of Candida albicans protein and polysaccharide antigens by human sera. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernando F L, Estevez J J, Cebrian M, Poulain D, Pontón J. Identification of Candida albicans cell wall antigens lost during subculture in synthetic media. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones J M. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive candidiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:32–45. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein R S, Harris C A, Butkus Small C, Moll B, Lesser M, Friendland G H. Oral candidiasis as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Valle R, Bromuro C, Ranucci L, Muller H M, Crisanti A, Cassone A. Molecular cloning and expression of a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4039–4045. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4039-4045.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee K L, Buckley M R, Campbell C. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1975;13:148–153. doi: 10.1080/00362177585190271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Ribot J L, Alloush H M, Masten B J, Chaffin W L. Evidence for presence in the cell wall of Candida albicans of a protein related to the hsp70 family. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3333–3340. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3333-3340.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Ribot J L, Casanova M, Gil M L, Martínez J P. Common and form-specific cell wall antigens of Candida albicans as released by chemical and enzymatic treatments. Mycopathologia. 1996;64:5239–5247. doi: 10.1007/BF00437047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Ribot J L, Chaffin W L. Binding of the extracellular matrix component entactin to Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4564–4571. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4564-4571.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Ribot J L, McAtee R K, Lee L N, Kirkpatrick W R, White T C, Sanglard D, Patterson T F. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with the development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2932–2937. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Ribot J L, Monteagudo C, Sepúlveda P, Casanova M, Chaffin W L. Expression of the fibrinogen binding mannoprotein and the laminin receptor of Candida albicans in vitro and in infected tissues. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;142:117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marot-Lebond A, Robert R, Aubry J, Ezcurra P, Senet J M. Identification and immunochemical characterization of a germ tube specific antigen of Candida albicans. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marr K A, White T C, van Burik J-A H, Bowden R A. Development of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans causing disseminated infection in a patient undergoing marrow transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:908–910. doi: 10.1086/515553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez J P, Gil M L, López-Ribot J L, Chaffin W L. Serologic response to cell wall proteins and mannoproteins of Candida albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:121–141. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews R C. Pathogenicity determinants of Candida albicans: potential targets for immunotherapy? Microbiology. 1994;140:1505–1511. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-7-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews R C, Burnie J P. The role of hsp90 in fungal infection. Immunol Today. 1992;13:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews R C, Burnie J P. Antibodies against Candida: potential therapeutics? Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:354–358. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patterson T F, Kirkpatrick W R, Revankar S G, McAtee R K, Fothergill A W, McCarthy D I, Rinaldi M G. Comparative evaluation of macrodilution and chromogenic agar screening for determining fluconazole susceptibility of Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3237–3239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3237-3239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson T F, Revankar S G, Kirkpatrick W R, Dib O, Fothergill A W, Redding S W, McGough D A, Rinaldi M G. A simple method for detecting fluconazole resistant yeast with chromogenic agar. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1794–1797. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1794-1797.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfaller M A. The use of molecular techniques for epidemiologic typing of Candida species. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1992;4:43–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2762-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pontón J, Jones J M. Analysis of cell wall extracts of Candida albicans by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot techniques. Infect Immun. 1986;53:565–572. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.565-572.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pontón J, Marot-Leblond A, Ezkurra P A, Barturen B, Robert R, Senet J M. Characterization of Candida albicans cell wall antigens with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4842–4847. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4842-4847.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poulain D, Hopwood V, Vernes A. Antigenic variability of Candida albicans. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1985;12:223–270. doi: 10.3109/10408418509104430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quindós G, Pontón J, Cisterna R, Mackenzie D W. Value of detection of antibodies to Candida albicans germ tube in the diagnosis of systemic candidiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:178–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01963834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Revankar S G, Kirkpatrick W R, McAtee R, Dib O P, Fothergill A W, Redding S W, McGough D A, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Detection and significance of fluconazole resistance in oropharyngeal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:821–827. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Pfaller M A. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sundstrom P M, Aliaga G R. Molecular cloning of cDNA and analysis of protein secondary structure of Candida albicans enolase, an abundant, immunodominant glycolytic enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6789–6799. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6789-6799.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sundstrom P M, Aliaga G R. A subset of proteins found in culture supernatants of Candida albicans includes the abundant, immunodominant, glycolytic enzyme enolase. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:452–456. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sundstrom P M, Jensen J, Balish E. Humoral and cellular responses to enolase after alimentary tract colonization or intravenous immunization with Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:390–395. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundstrom P M, Tam M R, Nichols E J, Kenny G E. Antigenic differences in the surface mannoproteins of Candida albicans as revealed by monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1988;56:601–606. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.3.601-606.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tronchin G, Bouchara J P, Robert R. Dynamic changes of the cell wall surface of Candida albicans associated with germination and adherence. Eur J Cell Biol. 1989;50:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]