Abstract

Service workers often endure sexual harassment from customers in the course of performing their work duties. This article includes two studies based upon psychological contract theory. Customer sexual harassment (CSH) is posited as a psychological contract breach, which predicts an affective response (i.e., psychological contract violation), and in turn, work and health-related outcomes. Both studies tested models using samples of customer service women from various professions. Using path analysis, Study 1 found support for the proposed model, finding significant indirect effects between CSH and emotional exhaustion and affective commitment via psychological contract violation. Study 2 expanded upon the results, finding additional evidence of mediation for burnout (emotional exhaustion, cynicism, professional efficacy), affective commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. This study adds to growing research highlighting the health and work-related costs of allowing CSH to persist. Results support the application of theory and raise concerns that organizations may be viewed as complicit in CSH, which in turn, is linked with health and job-related outcomes. Examining contract violation, a subjective appraisal of the organization, serves as a contribution to sexual harassment literature, which has focused on appraisal of the harassment itself and has not directly followed from theory. Future research could examine specifics regarding how harassment experiences might impact organizational perceptions via psychological contract theory. Drawing upon CSH and psychological contract literatures, approaches to prevention and intervention are discussed.

Keywords: Customer sexual harassment, Psychological contract theory, Burnout, Occupational health, Service work

Workers are frequently subject to customer misbehavior, including sexual harassment. In one of the first major studies of customer sexual harassment (CSH), Gettman & Gelfand (2007) found that a majority of service workers (86%) experienced sexually harassing behavior from customers, which was up to roughly twice the rate of harassment from organizational insiders (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007). Yagil (2008) reviewed a number of antecedents to CSH and customer aggression including excessive organizational tolerance of customer behavior, a power gap that favors the customer, lower status service providers, and dependence on the customer. Furthermore, she noted that norms of informality, working outside of the organization, customer alcohol consumption, and customer stress may contribute to customer-instigated aggression and sexual harassment. Corroborating these findings, more recent studies have linked customer power to dependence on tips and emotional labor (Kundro et al., 2021; Morganson & Major, 2014). CSH has been linked with higher worker stress, posttraumatic stress, and employee withdrawal from the customer as well as lower job satisfaction, health satisfaction, and affective commitment (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Morganson & Major, 2014). Compared to harassment from organizational insiders, CSH may be more difficult to address.

While current research documents that CSH is commonplace and problematic, understanding why it occurs and employing theory to its study is needed to understand and curb its occurrence. The present study aims to answer calls for more research examining CSH (Cortina & Berdahl, 2008; Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Morganson & Major, 2014; Quick & McFayden, 2017). As elaborated below, sexualized treatment from customers may be an implicit job requirement. It is, therefore, an institutionalized work hazard and barrier to women’s career development that, to date, has received insufficient attention. More specifically, the current manuscript applies psychological contract and affective response theories to examine service workers’ responses to CSH. Although CSH emanates from parties outside the organization (i.e., customers), the present study aims to tests how it impacts workers’ feelings toward the organization and, in turn, subsequent outcomes. In doing so, it also seeks to enrich sexual harassment literature, which has often lacked theoretical guidance (Willness et al., 2007).

Sexual Harassment Research

There exists a longstanding lack of theory guiding sexual harassment research, perhaps because sexual harassment emanated as a social problem rather than an academic one (Willness et al., 2007). Fitzgerald et al., (1995; 1997) presented a widely-cited model of organizational antecedents and outcomes of sexual harassment, which draws upon Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984, 1986) work and links sexual harassment to job-related, health-related and psychological outcomes. This line of theory is cognitively-based, and presumes that individuals may appraise sexual harassment experiences at varying levels of threat and severity, which in turn impacts harassment outcomes. Although appraisal is a core aspect of the foundational theory employed, sexual harassment studies do not typically incorporate appraisal as a factor. One exception is Langhout et al. (2005), who found that appraisal mediated the relationship between sexual harassment and outcomes. Cortina et al. (2002) tested subjective appraisal as a mediator and determined that sexual harassment and cognitive appraisal were heavily intertwined, to the point of being indistinguishable. The authors explained that sexual harassment may already incorporate the concept of appraisal by definition. For example, the behavior of the harasser is by definition unwanted; and not wanting something involves appraising it as undesirable.

While it may be the case that an individual’s cognitive appraisal and emotional reactions to sexual harassment experiences are intertwined, feelings toward the organization following sexual harassment have yet to be examined. The present study aims to build on prior research by examining psychological contract violation (i.e., one’s feelings toward the organization) as a mediator of the relationship between customer sexual harassment and outcomes. Whereas the (limited) theory that has guided sexual harassment research originated from the clinical and counseling literature (Lauzarus & Folkman, 1984, 1986), which may overemphasize the focus on the individual, the present study draws from organizational theory. Focusing on attributions of the organization rather than the harassment events is a subtle, but important distinction because it recognizes the organization’s involvement in the harassment process.

Legislation holds organizations responsible for preventing and addressing sexual harassment (EEOC, 1990). Even though customers are not direct agents of the organization, legal precedence suggests that even they may be viewed as responsible for CSH (EEOC, n.d.). As Yagil (2008) discussed, one of the conditions that fosters customer harassment and aggression is the tendency of organizations to deny and avoid drawing attention to customer misbehavior. Denial may be forced upon employees and flirtation and expression of sexuality may be a job requirement (Yagil, 2008). In academic literature, organizational context is a widely researched precursor to sexual harassment (Willness et al., 2007) and customer sexual harassment (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007). Additionally, recent research suggests that organizational policies (i.e., requiring emotional display expectations) and pay structures (i.e., reliance on tips) can increase the occurrence of CSH (Kundro et al., 2021). Thus, while research documents that organizations may be complicit in the occurrence of CSH, the application of psychological contract and affective events theory extends the research literature and suggests that CSH precipitates negative feelings toward the organization that impact employee health and job-related outcomes.

Psychological Contract Theory

Psychological contract theory is based upon the concept of social exchange and describes how employees and employers form mutual, reciprocal relationships based upon both expressed and implied commitments. The psychological contract refers to “an individual’s beliefs regarding reciprocal relationships” (Rousseau 1990, p. 390) from their employer. The psychological contract begins to develop at the onset of the employment relationship (Rousseau, 1990). Over time, employees come to view their expectations as obligations (Rousseau, 1990). Researchers have found that expectations include concrete issues such as salary, fringe benefits, working conditions and job tasks, as well as less tangible aspects such as a sense of being cared for by the organization and other socioemotional benefits (Armeli et el., 1998; Guzzo et al., 1994; Rousseau, 1995; Schalk & Roe, 2007).

Organizations may intentionally or inadvertently violate the psychological contract by failing to meet the employees’ expectations of the agreement (e.g., Robinson, 1996; Robinson & Rousseau, 1994). Morrison and Robinson (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Robinson & Morrison, 2000) defined psychological contract breach as a deviation or incongruence with expectation. Breach differs from violation, which refers to an emotional reaction following contract breach perceptions (Morrison & Robinson, 1997; Robinson & Morrison, 2000).

Psychological contract theory has been widely researched and has found a great deal of empirical support (Zhao et al., 2007). Psychological contract breach has been positively related to psychological contract violation, mistrust, and turnover intentions, as well as negatively linked with job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and in-role performance in meta-analysis (Zhao et al., 2007).

The notion that psychological contracts can be very broad has always been central to the theory in that they contain non-economic, socio-emotional, subjective, pervasive, and intrinsic aspects (Rousseau, 1990). Additional research on psychological contracts indicates that work ideologies and expectations about the context in which the employment relationship is embedded can also shape psychological contracts (Bunderson, 2001). Schalk and Roe (2007) argued that a psychological contract violation can occur when one’s basic values are threatened in a work situation. They provided responses from employees of a home-care organization who were asked what kinds of behavior they would perceive to be intolerable in their employment relationships. Responses included “If I were no longer able to build a relationship with clients or to provide quality care” and “If I were confronted with sexual harassment” (Schalk & Roe, 2007, p. 175). As noted above, sexual harassment is illegal (EEOC, 1990) and organizations are responsible for protecting their workers against customer sexual harassment (EEOC, n.d.). Based both upon psychological contract literature, legal obligations of employers, and the basic assumption that women desire to be taken seriously at work, the present study posits that experiencing CSH typically constitutes a psychological contract breach.

Robinson and Morrison (2000) predicted that breach temporally precedes psychological contract violation. More recently, meta-analytic results from two decades of research has tested psychological contract theory models (Zhao et al., 2007). Zhao et al. (2007) drew from both psychological contract and affective events theories, finding that the best fitting model is one in which breach (posed as an affective event) precedes violation (posed as an affective reaction). Violation, in turn, mediates the impact of breach on more distal outcomes such as attitudes and behavior.

Hypothesized Relationships

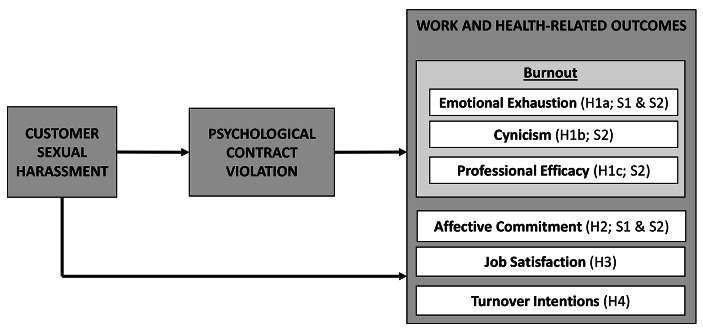

Drawing upon prior theory and research, the present study tests the model in Fig. 1. Psychological contract violation is hypothesized to mediate the relationship between CSH and work and health-related outcomes. In Study 1, affective commitment and emotional exhaustion were studied in order to account for both health and work-related outcomes. Emotional exhaustion is the most commonly reported and commonly researched aspect of job-related burnout (McCormack et al., 2018), and has been repeatedly linked with customer service work and customer-initiated aggression (e.g., Grandey et al., 2004, 2007; Greenbaum et al., 2014; Sliter et al., 2010). In Study 1, psychological contract violation was expected to mediate the links between CSH and emotional exhaustion (Hypothesis 1a) as well between CSH and affective commitment (Hypothesis 2).

Fig. 1.

Heuristic Diagram of Hypothesized Model

Study 2 aims to corroborate the general findings of Study 1 in another sample. It also aims to expand upon Study 1 by using a more common and multi-faceted measure of job-related burnout and examining more work-related variables. The inclusion of both work and health-related outcomes follows from Fitzgerald et al., (1997). As shown in Fig. 1, Study 2 hypothesized that psychological contract violation would mediate the relationship between CSH and aspects of burnout: emotional exhaustion (Hypothesis 1a), cynicism (Hypothesis 1b), and professional efficacy (Hypothesis 1c). Additionally, psychological contract violation was expected to mediate the relationship between CSH and affective commitment (Hypothesis 2), job satisfaction (Hypothesis 3), and turnover intention (Hypothesis 4).

Study 1

Study 1 Method

Participants and Procedure

Women are more likely to experience sexual harassment than men and are more likely to label their experience as harassment (Magley et al., 1999). Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Gettman & Gelfand 2007; Wasti & Cortina, 2002), the present study consisted of an exclusively female sample. A snowball technique was used to recruit female customer service workers from several sources. Participants were recruited via an online link shared on several listservs including professional societies and a mailing list for a women’s studies center at a campus at a large southeastern university. The link was also shared with contacts of the researcher who worked in service positions and it posted as an announcement for university employees. Those who received the invitation were invited to participate and to share the survey opportunity with other female customer service workers. So as not to bias responses, the term “sexual harassment” was not used in the recruitment messages. Rather, the survey was accurately and neutrally described as including items about both positive and negative work experiences. Participants were offered a one in ten chance to win $50 for their participation in the study. To be included in the study, participants were required to work a minimum of ten hours per week in a position that interfaces with customers, clients, or patients. These requirements were both included in the recruitment materials and verified in survey questions.

The study consisted of two surveys. The first survey was administered via a link in the recruitment message described above. At the end of the first survey, participants entered their email address. The researcher followed up with participants a month after their completion of the first survey to invite them to take a follow-up survey. CSH was temporally separated from the measurement of other variables to reduce concerns of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). There were a total of 173 participants who met the study criteria from survey 1 and were invited to participate in survey two. Of these participants, 127 responded to the survey with complete data and met the qualifications for the study in the second survey. An additional 20 participants were removed because they did not experience any sexualized mistreatment from customers based on the customer sexual harassment measure described in the next section.

The final sample (N = 107) included a wide variety of jobs. Examples include Project Manager, Senior Consultant, Counselor, Financial Advisor, Medical Assistant, Nurse Practitioner, Registered Dental Hygienist, Receptionist, Library Assistant, Hair Stylist, Teller, Customer Service Representative, and Field Claims Adjuster. Participants reported working an average of 40.28 (SD = 10.7) hours per week and had been in their careers 8.2 years (SD = 7.6). The average age was 36.9 years (SD = 12.0) Level of education spanned from high school diploma to doctoral degree with Master’s degree (25.4%), Bachelor’s degree (23.0%), Associate’s degree (15.9%) and some college (17.5%) being the most frequent responses. The vast majority of participants were White (85.7%), with some minority groups represented including African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and individuals reporting multiple races. Almost half (49.2%) of participants were married.

Measures

Customer Sexual Harassment. CSH was measured using a version of the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ; Fitzgerald et al., 1995), which was adapted to apply to customers (SEQ-C; Gettman & Gelfand 2007). The SEQ is supported by validation evidence (Fitzgerald et al., 1995) and is the most commonly used measure of sexual harassment (Willness et al., 2007). Gettman and Gelfand’s (2007) adaptation of the measure to refer to customers retains the original content validity while corroborating and extending the measure’s construct validity by linking it to antecedents and outcomes of CSH. The SEQ-C consists of 16 items, which reflect behavioral frequency of unwanted sexual attention, sexist hostility, sexual hostility, and sexual coercion. An example item is “[In the last two years, how often have you been in a situation where a customer or client…] …continued to ask you for dates, drinks, dinner, etc., even though you said ‘no’?” Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (most of the time) Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Psychological Contract Violation. Numerous measures of psychological contract breach and violation are available. The present study used four items from Robinson and Morrison (1997). Their measure is global and focuses purely on feelings toward the organization (vs. including items that may reflect expectations or breach). Robinson and Morrison (1997) present factor analytic support as well as linking violation to several related constructs. The measure is a theory-based, direct assessment. Whereas some other measures list potential contents of psychological contracts (e.g., training and promotional opportunities promised versus obtained) and offer an opportunity for item-level assessment in addition to aggregate scoring, a global measure was more appropriate for assessing the hypothesized relationships. Although measurement at the item-level is a desirable quality in some psychological contract studies, the present study was focused on a particular type of breach (i.e., CSH). Thus, measures asking participants to rate potential aspects of the psychological contract would introduce measurement contamination. Robinson and Morrison’s (1997) measure is recommended as a global assessment (Freese & Schalk, 2008). An example item is “I feel extremely frustrated by how I have been treated by my organization.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was 0.95.

Emotional Exhaustion. Emotional exhaustion was measured using five items from Wharton (1993). The authors provided factor analytic support for the measure as well as evidence of construct validity by finding negative relationships with emotional labor, job control, job satisfaction, and job involvement. An example item is “I feel emotionally drained from my work.” Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 7 (everyday). Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was 0.86.

Affective Commitment. Affective organizational commitment was measured using a facet of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) scale. Meyer et al. (1993) provided evidence of the reliability and construct validity for this measure. Participants rated their agreement or disagreement on a seven point scale in response to four items. An example item is “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.93.

Other Demographic Variables. Hours per week, age, and tenure were all evaluated as potential control variables. The rationale for the inclusion of these variables as potential controls is that hours per week impacts opportunity to be harassed and tenure impacts opportunity for burnout (Brewer & Shapard, 2004). Age is also a moderator of the relationship between psychological contract breach and job attitudes (Bal et al., 2008). Age is related to career stage and has been found to be related to affective commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1993). Younger workers may also be less aware of sexual harassment and more likely to be targeted (Yagil, 2008). However, none of these potential control variables were related to endogenous variables. Thus, consistent with Becker (2005), they were not included in testing the hypothesized model. Becker et al., (2016) also emphasized the importance of having a clear and strong rationale for control variables, warning that they may otherwise cloud interpretation of results.

Study 1 Results

Table 1 includes means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among variables. Models were tested using AMOS (Arbuckle, 2012). Prior to proceeding with hypothesis testing, a confirmatory factor analysis was used to assess the measurement model including CSH, psychological contract violation, emotional exhaustion, and affective commitment. Consistent with prior research (Fitzgerald et al., 1997; Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Morganson & Major, 2014), the sexual harassment measure was parceled. Parceling reduces the impact of distributional violations (Little et al., 2013) and therefore appropriate for sexual harassment because it tends to be skewed and kurtotic. Items were assigned to parcels by pairing together items with low and high item-total correlations to ensure each factor is similarly representative of CSH (Landis et al., 2000). CSH was comprised of three parcels. All other measures were reflected by individual items. Latent variables were allowed to correlate. Several statistics were used to assess model fit including the chi-square (χ2) statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Chi-square is considered favorable when smaller and non-significant. CFI is considered to indicate good fit when it exceeds 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). However, SRMR values below 0.10 are generally considered favorable (Kline, 2011). RMSEA values below 0.05 indicate good fit and below 0.08 as acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1989). Hu and Bentler (1998; p. 449) suggested an RMSEA “close to .06” and noted that the value will tend to be higher in smaller samples. The model demonstrated acceptable to good fit, χ2(98) = 159.71, p = .001, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.07. Although the chi-square test was significant, it tends to be sensitive to non-normality and correlations between factors (Kline, 2011).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among Study 1 variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 36.28 | 11.88 | ||||||

| 2. Tenure | 8.15 | 7.70 | 0.59*** | |||||

| 3. Hours | 4.47 | 11.05 | 0.20* | 0.09 | ||||

| 4. CSH (T1) | 1.55 | 0.49 | − 0.15 | − 0.09 | − 0.05 | |||

| 5. Psychological Contract Violation (T2) | 1.96 | 0.97 | − 0.04 | 0.11 | − 0.06 | 0.19 | ||

| 6. Emotional Exhaustion (T2) | 3.71 | 1.10 | − 0.07 | − 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.52*** | |

| 7. Affective Commitment (T2) | 4.44 | 1.25 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.03 | − 0.13 | − 0.35*** | − 0.30*** |

Note. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Structural equation modeling guidelines suggest using a sample of at least 200 participants (Kline, 2011) or five to ten participants per parameter estimated (Bentler & Chou, 1987). Due to sample size, path analysis (non-latent) was used to test hypotheses. Bootstrapping with 5,000 samples and 95% confidence intervals were used to test mediation. Because sample size was small and sexual harassment tends to be non-normally distributed, bootstrapping was used in reporting of all paths in the model.

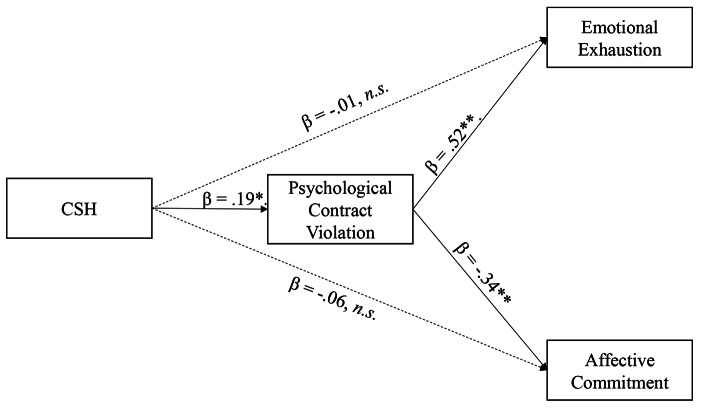

Path model results for Study 1 are reported in Fig. 2. In support of Hypothesis 1a, CSH had an indirect effect on emotional exhaustion through psychological contract violation of (β = 0.10, SE = 05, p = .04, (95% CI =-0.01, 0.19)). In support of Hypothesis 2, CSH had an indirect effect on affective commitment through psychological contract violation (β = − 0.07, SE = 0.04, p = .04 (95% CI = − 0.01, − 0.14)).

Fig. 2.

Bootstrapped standardized path coefficients for Study 1 model

Study 2

Study 2 Method

Participants and Procedure

Similar to Study 1, to reduce response bias, the term “sexual harassment” was not used in recruiting. Women working customer service positions were recruited to participate in this study via two human subjects participant pools. First, students from a large southeastern university in the United States participated for extra credit in their courses. The survey was made available only to students who indicated in a pre-screen survey that they were women, worked in addition to their studies, and were over the age of 18. Reminders were sent to participants who did not complete the second survey within the first few days.

Data collection consisted of two online surveys spaced two weeks apart. CSH was measured at time 1 and outcomes (i.e., psychological contract violation, job-related burnout, affective commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions) were measured at time 2. Data between the prescreen and both surveys were matched for consistency and carefully cleaned. Responses within the main surveys were used to verify that all participants worked at least ten hours per week in a customer service job. Only participants who indicated having experienced at least one sexually harassing behavior on the CSH measure were included in analyses. The final sample consisted of 187 participants.

Participants were an average of 23.0 years old (SD = 5.7), worked an average of 23.9 h per week (SD = 9.6), and worked in their field for an average of 6.7 years (SD = 3.4). Most participants were single (84.4%) and earned less than $20,000 per year (77.3%). A majority of participants identified as White (64.7%), followed by African American (26.7%), Asian (5.3%), Hispanic (3.2%), or another race/ethnicity. Job titles included Sales Associate, Server, Caretaker, Bartender, Accountant, Server, Office Assistant, Front Desk Clerk, Event staff, Registered Nurse, Driver, Receptionist, Barista, and Veterinary Tech.

Measures

Customer Sexual Harassment. Similar to Study 1, CSH was measured with the SEQ-C (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007). The alpha was 0.89.

Psychological Contract Violation. Psychological contract violation was assessed with the same measure as in Study 1 (alpha = 0.94).

Job-Related Burnout. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach & Jackson 1981) was used to assess three facets of job-related burnout. The MBI has been supported with evidence of reliability and validity across contexts and populations and is the most widely used measure of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Poghosyan et al., 2009). The response scale ranged from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The emotional exhaustion component consisted of five items (alpha = 0.92). An example item is “I feel burned out from my work.” The cynicism dimension consisted of four items (alpha = 0.85), e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my work.” The professional efficacy subscale consisted of six items (alpha = 0.86), e.g., “I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job.”

Affective Commitment. As in Study 1, affective commitment was assessed using four items from Meyer et al. (1993), alpha = 0.88.

Job Satisfaction. Job satisfaction was measured using the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MQAQ-JSS; Cammann et al., 1979). The measure has shown strong validity evidence using meta-analysis (Bowling & Hammond, 2008). The alpha for the measure was 0.90.

Turnover Intentions. Turnover intentions were assessed via Peters et al. (1981) measure. Peters et al. (1981) linked their measure to job satisfaction, job search behavior, and actual turnover in a sample of full-time workers. Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example item is “I often think about quitting.” The alpha for this three items was 0.91.

Other Demographic Variables. Similar to Study 1, age, tenure, and hours per week were all evaluated as potential control variables. Age was unrelated to dependent variables and was therefore omitted as a control (Becker, 2005; Becker et al., 2016). Tenure was related to the professional efficacy facet of job-related burnout. Hours worked per week was related to emotional exhaustion, and cynicism. Accordingly, tenure and hours worked per week were evaluated as potential control variables on these variables only. The results for models with and without control variables were compared. The inclusion of control variables did not significantly impact the results. Rather, they had an impact that was not detectible after rounding to the nearest tenth. Thus, results without control variables are presented.

Study 2 Results

Table 2 reflects means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables. As with Study 1, AMOS was used to assess the measurement model and non-latent a mediated path model. Models were bootstrapped with 5,000 samples and 95% confidence intervals. The measurement model was comprised of eight correlated latent variables representing customer sexual harassment (reflected by parcels as in Study 1), contract violation, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, professional efficacy, affective commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Model fit was good to acceptable, χ2(499) = 931.4, p = .000, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.07. As noted in Study 1, the chi-square test is sensitive to non-normality and correlations between factors as noted above (Kline, 2011).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among Study 2 variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 22.98 | 5.74 | ||||||||||

| 2. Tenure | 3.66 | 3.38 | 0.51*** | |||||||||

| 3. Hours | 22.93 | 9.62 | 0.38*** | 0.31*** | ||||||||

| 4. CSH (T1) | 1.85 | 0.56 | − 0.05 | − 0.01 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 5. Psychological Contract Violation (T2) | 2.18 | 1.06 | 0.12 | − 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.22** | ||||||

| 6. Emotional Exhaustion (T2) | 3.64 | 1.52 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.29*** | 0.22** | 0.53*** | |||||

| 7. Cynicism (T2) | 3.41 | 1.50 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.16* | 0.29*** | 0.53*** | 0.59*** | ||||

| 8. Professional Efficacy (T2) | 5.49 | 1.26 | 0.13 | 0.18* | 0.13 | − 0.12 | − 0.31*** | − 0.08 | − 0.22** | |||

| 9. Affective Commitment (T2) | 4.39 | 1.48 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.15* | − 0.20** | − 0.51*** | − 0.28*** | − 0.44*** | 0.32*** | ||

| 10. Job Satisfaction (T2) | 3.38 | 1.02 | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | − 0.22** | − 0.60*** | − 0.44*** | − 0.61*** | 0.35*** | 0.64*** | |

| 11. Turnover Intentions (T2) | 2.96 | 1.18 | 0.05 | 0.02 | − 0.01 | 0.20** | 0.64*** | 0.46*** | 0.58*** | − 0.32*** | − 0.57*** | − 0.81*** |

Note.*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Indirect effects are listed in Table 3 and path coefficients are listed in Table 4. Similar to Study 1 and in support of Hypothesis 1a, CSH had an indirect effect on emotional exhaustion through psychological contract violation of β = 0.12, SE = 0.04, p = .001 (95% CI = 0.05, 0.21). In support of Hypotheses 1b and 1c, psychological contract violation mediated the relationship between CSH and the other two aspects of burnout as well: cynicism [β = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .001 (95% CI = 0.04, 0.21)] and professional efficacy [β = − 0.07, SE = 0.03, p = .001, (95% CI = − 0.13, − 0.02)]. Similar to Study 1 and in support of Hypothesis 2, the indirect effect of CSH on affective commitment was significant, β = − 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .001 (95% CI =− 0.18, − 0.04). Supporting Hypothesis 3 and 4, CSH had an indirect effect on job satisfaction [β =− 0.13, SE = 0.04, p = .001 (95% CI =− 0.22, − 0.05)] and turnover intentions [β = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p = .001 (95% CI = 0.06, 0.23)].

Table 3.

Study 2 bootstrapping results for standardized indirect effect of csh on work and health-related outcomes variables via psychological contract violation

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Standardized Indirect Effect |

SE | LL | UL |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.12** | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| Cynicism | 0.11** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Professional efficacy | − 0.07** | 0.03 | − 0.13 | − 0.02 |

| Affective commitment | − 0.11** | 0.04 | − 0.18 | − 0.04 |

| Job satisfaction | − 0.13** | 0.04 | − 0.22 | − 0.05 |

| Turnover intentions | 0.14** | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

Note. CI = confidence interval, LL = lower limit, UL = upper limit. Results are based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. CIs are two-tailed. ** p < .01.

Table 4.

Results for standardized path coefficients

| Dependent Variable | Standardized Effect | Unstandardized Effect | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSH | ||||

| Psychological Contract Violation | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.089 |

| Cynicism | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.005 |

| Professional efficacy | − 0.04 | − 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.537 |

| Affective commitment | − 0.09 | − 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.159 |

| Job satisfaction | − 0.09 | − 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.126 |

| Turnover intentions | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.289 |

| Psychological Contract Violation | ||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.000 |

| Cynicism | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.000 |

| Professional efficacy | − 0.30 | − 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.000 |

| Affective commitment | − 0.49 | − 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.000 |

| Job satisfaction | − 0.58 | − 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.000 |

| Turnover intentions | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.000 |

Discussion

The present studies provide support for a model based upon psychological contract and affective events theories. In these two studies, CSH was posed and supported as an affective event that predicts a negative feeling toward one’s organization (i.e., a psychological contract violation), and in turn, job and health-related outcomes (i.e., higher emotional exhaustion, cynicism and turnover intentions as well as lower professional efficacy, job satisfaction, and affective commitment).

A key contribution of these studies is to link the CSH process to attributions toward the organization. Competition on the basis of customer service may lead organizations to empower customers, perhaps ignoring their misbehavior and endorsing a philosophy that the customer is always right. However, the application of psychological contract theory suggests that, while customers may perceive themselves as “right” and organizations may be complicit in creating this perception or norm (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Yagil, 2008), employees often do not agree. The findings of these studies suggest that employee perceptions of the organization following the experience of CSH are linked with a variety of adverse outcomes.

Although organizations are required to take reasonable steps to address harassment from customers or they may be held liable, legal cases involving CSH are relatively rare compared to sexual harassment cases regarding organizational insiders as perpetrators (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007). Thus, Gettman and Gelfand (2007) called for more research to explain the relative lack of cases and reports. The application of psychological contract theory may help explain the relative lack of legal precedence regarding CSH. Whereas legal contracts and documents are explicit, psychological contracts contain both explicit and implicit components. While sexual harassment from organizational insiders is more explicitly prohibited (e.g., by training, whistle blowing procedure, clear organizational policy), CSH may be implicitly tolerated due to organizational norms and perhaps even internalized by targets of harassment themselves. However, the relative lack of lawsuits should not be taken as reason to overlook CSH. The results of this study and others linking CSH to work and health-related outcomes (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Morganson & Major, 2014) suggests that organizations are likely to incur costs for failure to address CSH. Although lawsuits are costly, they are just one of several costs of discrimination (Burns, 2012) and may be relatively uncommon compared to incidence rates of harassment (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Ilies et al., 2003). In contrast, the costs of employee burnout, lowered job satisfaction, and increased turnover are likely more pervasive and common for most employers; and thus, should be considered as business rationale for confronting customer harassment of employees. Exiting the organization is a more likely outcome of psychological contract breach than voicing concerns (Turnley & Feldman, 1999). Additionally, employees who experience CSH may respond in other counterproductive ways that are consistent with experiencing psychological contract violation such as by retaliating toward the customer (Morganson & Major, 2014).

Borrowing theory from organizational scholarship may help advance sexual harassment research. As discussed in the introduction, psychological contract theory differentiates between contract breach (cognitive) and violation (emotional; Robinson & Morrison 2000). When appraisal has been examined in the sexual harassment literature, the measure used (Swan, 1997) appears to include cognitive and emotional items. Being treated with dignity in the workplace may be a “given” with regard to employee expectations and may therefore be implicit in the definition and measure of sexual harassment as Cortina et al. (2002) suggested. However, individuals seem to vary in their emotional response to harassment, which appears to be distinct from the harassment itself and the job and health-related variables studied herein. Additionally, when subjected to sexual harassment, subjective appraisals may be directionally charged. These studies examined contract violation as a subjective appraisal directed toward the organization. However, future research might also examine appraisal of the harasser. Distinguishing perceptual targets could be a useful direction for future research, perhaps as a way of benchmarking whether the organization is seen as sufficiently taking action to address CSH through the eyes of those who have experienced customer harassment firsthand.

In addition to theory application and testing, this study also extends the nomological network of CSH to include job-related burnout and its facets. As Gettman and Gelfand (2007) pointed out that academic literature “problemized” (p. 758) sexual harassment in the 1980s, and CSH may need to undergo the same process. The present study is one of a handful of studies to do so.

Practical Implications

Managers should monitor employee needs and respond with sincere effort to fulfill their moral and legal obligation, demonstrating authentic concern for employee well-being when CSH occurs. Perhaps employees can also be trained to be aware of CSH so that they feel empowered to respond to customer mistreatment when it occurs, but with the expectation that burden of responding should not be solely upon the target. Bystanders can also play an important role in CSH intervention (Liang & Park, 2022).

Although sexual harassment is a legal issue, thinking of its costs and risks from this perspective is limiting. As noted above, there are more likely costs to the organization. The costs of employee turnover becomes more salient when unemployment is low. At present, as organizations strive to recover from the impacts of Covid-19 and employees are reluctant to return to their front-line service jobs (Lund et al., 2021), employee wellness may be a strong strategic basis of competition for organizations. Aside from reducing the negative outcomes of psychological contract breach, organizations perceived as fulfilling their expectations via social exchange may reap benefits including customer-directed organizational citizenship behaviors, which may ultimately result in higher customer satisfaction (Bordia et al., 2010).

Stress literature would suggest that it is most effective to avoid CSH before it occurs via prevention (Cooper & Cartwright, 1997). Research has robustly shown that having clear policies and norms against sexual harassment is important for its prevention (Willness et al., 2007). Organizations should take care to ensure that employees and customers are aware of its anti-harassment policies. As the application of psychological contract theory supports, they may otherwise be seen as complicit in the employee’s experience. Setting clear expectations (e.g., training and socializing customers) may be useful in reducing the occurrence of CSH as well. Recent research also suggests that changes in role and pay structure may be helpful in curbing CSH. Policies that prescribe employee behavior and emotional displays (i.e., emotional labor) may exacerbate the impacts of CSH (Kundro et al., 2021). Likewise, employee financial dependence on customers via tips increases risk of CSH (Kundro et al., 2021). Charging customers and paying employees a pre-set amount may be more conducive to ensuring that expectations are shared. In addition to decreasing CSH, when expectations are shared and explicit from the start by all parties, psychological contract violations are less likely to occur.

Limitations and Future Research

The primary limitation of these studies is that they are cross-sectional in nature and rely on participants recalling experiences of CSH. Psychological contract violation and outcome variables were both measured in the second survey. It is plausible and likely that besides CSH, respondents had other experiences between the two surveys that impacted how they rated psychological contract violation and outcome variables. Although collecting data at two time points reduces concerns of common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), causality cannot be determined. Using cross-sectional designs is an important contribution and a precursor to more dynamic study designs (Spector, 2019); yet, more research is needed to examine the impacts of CSH over time and as it occurs. Pinpointing causality in sexual harassment research may be challenging because the timing of impact of CSH is currently unknown and experimentally manipulating sexual harassment raises ethical questions. Nonetheless, it would be valuable to examine the cumulative impacts of instances of harassment and to examine whether there is a point at which intervention tends to be most effective. Longitudinal research could be particularly useful to determine the short-term and long-term consequences of different approaches to addressing CSH. Although it may be normative to defer to the customer, research examining the long-term and compounding effects of enabling severe instances of customer misbehavior such as CSH could help motivate managers and organizations to better protect their workers. Case studies are rare in organizational research, but perhaps could be useful in informing managers on how to best respond while balancing the needs of the organization and employee when CSH occurs.

A limitation of Study 1 is its small sample size considering the complexity of the model. However, results were generally supported and replicated in Study 2. Additional research may seek to examine the impact of CSH upon mental health. CSH has been linked to posttraumatic stress symptoms (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007; Morganson & Major, 2014), stress, and health satisfaction in prior research (Gettman & Gelfand, 2007).

The present study used a global evaluation measure of psychological contract violation, but some psychological contract measures are more specific. The advantages of using a global evaluation over a more specific measure is that specific measures may not contain the items representing the elements of the psychological contract that were unmet (Conway & Briner, 2005), which the case when the type of breach is sexual harassment. However, specific measures may be more diagnostic (Freese & Schalk, 2008). As a follow-up from the present study, perhaps future research could develop a content-valid specific measure of psychological contract violation based on prior literature. Such a measure might contain example items about whether norms support CSH, if managers adequately addressed instances of CSH, and whether coworkers served as constructive bystanders. Specific, diagnostic assessment may be important for intervention because what is effective in one context may not be as effective in another.

Conclusions

Two studies tested a model based upon psychological contract and affective event theories. Results supported that CSH is a precursor to psychological contract breach, which in turn relates to a variety of job and health-related outcomes including psychological burnout (emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy), affective commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover. These studies build upon growing literature raising awareness and concern for CSH as a detriment to individuals and organizations alike. The application of psychological contract theory informs sexual harassment literature and implies that harassment targets may view the organization as complicit in CSH. More research is needed, especially to inform best practice on responding to CSH across varying contexts.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors declare they have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The data collection using human subject participants was deemed exempt by a University Institutional Review Board (1899367-2).

Consent to participate

All participants completed an electronic informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented to submit this manuscript for publication in Occupational Health Science.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arbuckle JL. IBM SPSS Amos 21 Users Guide. Chicago, IL: IBM Software Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Eisenberger R, Fasolo P, Lynch P. Perceived organizational support and police performance: The moderating influence of socioemotional needs. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1998;83(2):288–297. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal PM, De Lange AH, Jansen PGW, Van Der Velde MEG. Psychological contract breach and job attitudes: A meta-analysis of age as a moderator. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2008;72(1):143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TE. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods. 2005;8:274–289. doi: 10.1177/1094428105278021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TE, Atinc G, Breaugh JA, Carlson KD, Edwards JR, Spector PE. Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2016;32:157–167. doi: 10.1002/job.2053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. H. Practical issues in structural modeling.Sociological Methods & Research, 16,78–117. 10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Bordia P, Restubog SLD, Bordia S, Tang RL. Breach begets breach: Trickle-down effects of psychological contract breach on customer service. Journal of Management. 2010;36(6):1578–1607. doi: 10.1177/0149206310378366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling NA, Hammond GD. A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2008;73(1):63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer E, Shapard L. Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review. 2004;3:102–123. doi: 10.1177/1534484304263335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Single sample cross-validation indices for covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1989;24(4):445–455. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2404_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunderson JS. How work ideologies shape the psychological contracts of professional employees: Doctor’s responses to perceived breach. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22(7):717–741. doi: 10.1002/job.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C. (2012). The costly business of discrimination. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/reports/2012/03/22/11234/the-costly-business-of-discrimination/

- Cammann C, Fichman M, Jenkins D, Klesh J. The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Ann Arbor: Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Conway N, Briner RB. Understanding psychological contracts at work. A critical evaluation of theory and research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CL, Cartwright S. An intervention strategy for workplace stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;43:7–16. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, L. M., & Berdahl, J. L. (2008). Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. In J. Barling, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Behavior: Volume I - Micro Approaches. SAGE Publications Ltd

- Cortina LM, Fitzgerald LF, Drasgow FD. Contextualizing Latina experiences of sexual harassment: Preliminary tests of a structural model. Basic and Applied Psychology. 2002;87:230–242. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2404_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EEOC (n.d.). Sexual harassment. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/sexual-harassment

- EEOC (1990). Policy guidance on current issues of sexual harassment. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/policy-guidance-current-issues-sexual-harassment

- Fitzgerald LF, Gelfand MJ, Drasgow F. Measuring sexual harassment: theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1995;17:425–445. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp1704_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald LF, Drasgow F, Hulin CL, Gelfand MJ, Magley VJ. Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82(4):578–589. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese C, Schalk R. How to measure the psychological contract? A critical criteria-based review of measures. South African Journal of Psychology. 2008;38(2):269–286. doi: 10.1177/008124630803800202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gettman HJ, Gelfand MJ. When the customer shouldn’t be king: Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment by clients and customers. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:757–770. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Dickter DN, Sin HP. The customer is not always right: Customer aggression and emotion regulation of service employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2004;25(3):397–418. doi: 10.1002/job.252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Kern JH, Frone MR. Verbal abuse from outsiders versus insiders: Comparing frequency, impact on emotional exhaustion, and the role of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2007;12(1):63–79. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum RL, Quade MJ, Mawritz MB, Kim J, Crosby D. When the customer is unethical: The explanatory role of employee emotional exhaustion onto work–family conflict, relationship conflict with coworkers, and job neglect. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2014;99(6):1188–1203. doi: 10.1037/a0037221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutek, B. A. (1995). The dynamics of service: Reflections on the changing nature of customer/provider interactions. Jossey-Bass

- Guzzo RA, Noonan KA, Elron E. Expatriate managers and the psychological contract. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79(4):617–626. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.4.617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilies R, Hauserman N, Schwochau S, Stirbal J. Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Personnel Psychology. 2003;56:607–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00752.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press

- Kundro TG, Burke V, Grandey AA, Sayre GM. A perfect storm: Customer sexual harassment as a joint function of financial dependence and emotional labor. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1037/apl0000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis RS, Beal DJ, Tesluk PE. A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:186–207. doi: 10.1177/109442810032003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langhout RD, Bergman ME, Cortina LM, Fitzgerald LF, Drasgow F, Williams JH. Sexual harassment severity: Assessing situational and personal determinants and outcomes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2005;35:975–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02156.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: NY Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1986). Cognitive theories of stress and the issue of circularity. In M. H. Appley & R. Tnunbull (Eds.), Dynamics of stress: Physiological, psychological, and social perspectives (pp. 63–80). New York, Ny: Plenum

- Liang, Y., & Park, Y. (2022). Because I know how it hurts: Employee bystander intervention in customer sexual harassment through empathy and its moderating factors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(3), 339–348. 10.1037/ocp0000305 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, Schoemann AM. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods. 2013;18:285–300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund, S., Madgavkar, A., Manyika, J., Smit, S., Ellingrud, K., & Robison, R. (2021, February 18). The future of work after COVID-19. McKinsley Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19

- Magley VJ, Hulin CL, Fitzgerald LF, DeNardo M. Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999;84(3):390–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1981;2:99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack HM, MacIntyre TE, O’Shea D, Herring MP, Campbell MJ. The prevalence and cause(s) of burnout among applied psychologists: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1897. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review. 1991;1:61–91. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78:538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morganson VJ, Major DA. Exploring retaliation as a coping strategy in response to customer sexual harassment. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 2014;71:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0373-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EW, Robinson SL. When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review. 1997;22:226–256. doi: 10.2307/259230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters LH, Jackofsky EF, Salter JR. Predicting turnover: A comparison of part-time and full-time employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1981;2:89–98. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Aiken LH, Sloane DM. Factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory: an analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46(7):894–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick JC, McFadyen MA. Sexual harassment: Have we made any progress? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(3):286–298. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SL. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1996;41:574–599. doi: 10.2307/2393868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SE, Morrison EW. Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1994;15:245–259. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SL, Morrison EW. The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2000;21:525–546. doi: 10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<525::AID-JOB40>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau DM. New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1990;11:389–400. doi: 10.1002/job.4030110506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau DM. Psychological contracts in organizations. Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schalk R, Roe RE. Towards a dynamic model of the psychological contract. Journal of the Theory of Social Behavior. 2007;37:167–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sliter M, Jex S, Wolford K, McInnerney J. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2010;15(4):468–481. doi: 10.1037/a0020723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34, 125–137. 10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

- Swan, S. C. (1997). Explaining the job-related and psychological consequences of sexual harassment in the workplace: A contextual model. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Turnley WH, Feldman DC. The impact of psychological contract violations on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Human Relations. 1999;52(7):895–922. doi: 10.1177/001872679905200703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasti SA, Cortina LM. Coping in context: Sociocultural determinants of responses to sexual harassment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(2):394–405. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton AS. The affective consequences of service work: Managing emotions of the job. Work and Occupations. 1993;20:205–232. doi: 10.1177/0730888493020002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willness CR, Steel P, Lee K. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology. 2007;60:127–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00067.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yagil D. When the customer is wrong: A review of research on aggression and sexual harassment in service encounters. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wayne SJ, Glibkowski BC, Bravo J. The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology. 2007;60:647–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00087.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

N/A.

N/A.