Abstract

Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) are at increased risk of developing gastric neoplasms. However, endoscopic findings have not been sufficiently investigated. We investigated the phenotypic expression of gastric adenoma (low-grade dysplasia) and gastric cancer (high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma) in patients with FAP and clarified their relationships to endoscopic findings. Of 29 patients with FAP who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy between 2005 and 2020, 11 (38%) had histologically confirmed gastric neoplasms, including 23 lesions of gastric adenoma and 9 lesions of gastric cancer. The gastric neoplasms were classified into 3 phenotypes (gastric, mixed, or intestinal type) according to the immunostaining results and evaluated for location (U or M region: upper or middle third of the stomach or L region: lower third of the stomach), color (same as the background mucosa, whitish, or reddish), macroscopic type (elevated, flat, or depressed), background mucosal atrophy (present or absent), fundic gland polyps in the surrounding mucosa (present or absent), and morphologic changes in tumor size. Elevated whitish gastric adenomas were further subdivided by macroscopic type (flat elevated, protruded, or elevated with a central depression) and color (milky- or pinkish-white). The gastric adenomas included gastric (11/23, 48%), mixed (4/23, 17%), and intestinal (8/23, 35%) phenotypes. In contrast, no lesions of gastric cancers showed a gastric phenotype (0/9, 0%), while 5 (56%) and 4 (44%) lesions were intestinal and mixed phenotypes, respectively. Gastric cancers were significantly more likely than gastric adenomas to present as reddish depressed lesions with gastric atrophy. All gastric-type adenomas occurred in non-atrophic mucosa, in mucosa with fundic gland polyps in the periphery, in the U or M region, and as flat elevated or protruded lesions with a milky-white color. Half of the lesions increased in size. Meanwhile, the typical endoscopic features of intestinal-type adenomas included occurrence in the L region and elevated pinkish-white lesions with central depression. None of the intestinal-type adenomas increased in size during the observation period. We believe that these endoscopic features will be useful for the prompt diagnosis and appropriate management of gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP.

Keywords: familial adenomatous polyposis, gastric adenoma, gastric cancer, phenotypic variations

1. Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is a rare, autosomal dominant, inherited cancer susceptibility syndrome caused by a constitutional pathogenic variant of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Patients with FAP are characterized by the development of hundreds to thousands of polyps in the colon and rectum.[1,2] Without appropriate surveillance and treatment, individuals with classic FAP develop colorectal carcinoma around 40 years of age.[3] The most frequent cause of death in patients with FAP is colorectal cancer, which accounts for 60.6% of FAP-related deaths in Japan. However, the prognosis of patients with FAP has improved in recent years owing to the establishment of indications for prophylactic colectomy.

In addition to colorectal cancer, patients with FAP have significant risks for various neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. For instance, various gastric lesions are known to occur in the stomachs of patients with FAP, including fundic gland polyps, gastric adenomas, and gastric cancers. Gastric cancer-related deaths account for 2.8% of those among Japanese patients with FAP.[4] The risks of gastric adenoma (14.7%–39%[5,6] vs 2%–14%[7,8]) and gastric cancer (2.6%–7%[4,5,9] vs 0.6%–1.3%[10,11]) are higher in Japan compared to Western populations. However, a recent study from the United States reported a rapid increase in the incidence of gastric cancer in FAP.[11] Intramucosal carcinoma (high-grade dysplasia) is present in up to 14% of adenomas in patients with FAP.[12] Moreover, some gastric adenomas reportedly progress to gastric cancer.[13] In this context, gastric adenomas in patients with FAP may be considered precancerous lesions. Thus, early detection of both gastric neoplasms and colorectal lesions is important in patients with FAP.

Phenotypic classification of gastric neoplasms using mucin and brush border expression has been widely investigated in sporadic cases. These phenotypic markers reflect the endoscopic features, proliferative potential, biological behavior, and prognosis of gastric neoplasms.[14–20] However, the prevalence, phenotypic expression, endoscopic features, and prognosis of gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP have not been sufficiently investigated and remain unclear. Therefore, we investigate the phenotypic expression of gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP, primarily to clarify their relationship with the endoscopic findings. We also evaluated the changes in lesion size over time in adenomas according to their phenotype.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

Between January 2005 and December 2020, 42 patients with FAP were treated at Okayama University Hospital, Japan. Among them, 29 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy were enrolled in this study. Data regarding endoscopic, radiological, and biological examinations were retrospectively reviewed from clinical records. Gastric neoplasms histologically confirmed by endoscopic biopsy and/or resected specimens were evaluated for the expression of mucin and brush border markers and classified according to the immunostaining results.

First, we classified the gastric neoplasms into gastric adenoma and gastric cancer groups and compared their clinicopathological features. Subsequently, we further subcategorized adenomas according to their mucin expression and compared the endoscopic features between the groups.

2.2. Endoscopic findings

All endoscopic images obtained during the follow-up period in patients with FAP were retrospectively reviewed. The endoscopic images were evaluated by 2 board-certified endoscopists (M. K. and M. I.). Gastric neoplasms were evaluated for location (U or M region: upper or middle third of the stomach or L region: lower third of the stomach), color (same as the background mucosa, whitish, or reddish), macroscopic type (elevated, flat, or depressed), background mucosal atrophy (present or absent), and fundic gland polyps in the surrounding mucosa (present or absent). Whitish gastric adenomas were further subdivided into milky-white or pinkish-white. We subclassified elevated adenomas as flat elevated, protruded, and elevated lesions with a central depression. Morphological changes in the tumor size of the lesion were evaluated by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in gastric adenomas with >1 year of follow-up. We defined tumor enlargement as an increase of ≥5 mm.

The extent of gastric atrophy was endoscopically determined according to the Kimura–Takemoto classification, which correlates with the histological degree of atrophic gastritis.[21]

Heliobacter pylori (H pylori) infection status was determined according to the results of urea breath tests, rapid urease tests, microscopic observations, or culture tests on endoscopically biopsied specimens, stool antigen tests, serum or urine antibody tests, or a combination of these methods.

2.3. Histopathology

Endoscopic biopsy specimens and endoscopically resected specimens, including gastric neoplasms, were reviewed. When multiple biopsy specimens were obtained from 1 gastric neoplasm during the follow-up period, the most recently collected specimen was used for the analysis. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks were cut into 4-μm-thick sections. Immunohistochemical staining was performed for MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, CD10, and CDX-2. The immunostaining results were considered positive when ≥10% of the neoplastic cells were stained.

We classified each gastric neoplasm as gastric, mixed, or intestinal phenotypes. Gastric type lesions were positive for MUC5AC and/or MUC6 but negative for MUC2, CD10, and CDX-2. Mixed-type lesions were positive for MUC5AC and/or MUC6 and positive for MUC2, CD10, and/or CDX-2. Intestinal lesions were negative for MUC5AC and MUC6, but positive for MUC2, CD10, or CDX-2. The histopathological diagnosis was confirmed by an expert pathologist (T. T.).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact and chi-square tests were used to assess the statistical significance of clinical and endoscopic features between the groups. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP Pro 15 software program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

2.5. Ethics approval

This single-institutional retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institutional review board (registry no: 2004-013).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of patients with FAP

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of 29 patients with FAP (15 men and 14 women), 22 (88%), 2 (8%), and 1 (4%) were classified as having classical FAP, attenuated FAP, and Gardner syndrome, respectively. Most patients (27/29, 93%) had a history of colectomy, with a median age at colectomy of 33 years (range: 13–56). Seventeen patients (59%) had an obvious family history of FAP. Eight (42%) of 19 tested patients were positive for pathogenic germline mutations in APC. Twelve patients (41%) had extra-gastrointestinal lesions, including desmoid (9 patients), breast cancer (1 patient), esophageal cancer in Barrett’s esophagus (1 patient), acute lymphocytic leukemia (1 patient), and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (1 patient).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Patients with gastric neoplasm, n = 11 | Patients without gastric neoplasm, n = 18 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 5 (45%)/6 (55%) | 10 (56%)/8 (44%) | .71 |

| Types of FAP* | |||

| Classical | 8/9 (89%) | 14/16 (88%) | .23 |

| Attenuated | 0/9 (0%) | 2/16 (13%) | |

| Gardner syndrome | 1/9 (11%) | 0/16 (0%) | |

| History of colectomy | 11/11 (100%) | 16/18 (89%) | .51 |

| Median age at colectomy, yrs (range) | 34.9 (13–53) | 33.8 (24–56) | |

| Familial history of FAP† | 5/8 (63%) | 12/17 (71%) | 1.00 |

| APC pathogenic variant‡ | 3/5 (60%) | 5/14 (38%) | 1.00 |

| Extra-gastrointestinal lesions§ | 6/11 (55%) | 6/18 (33%) | .70 |

| Fundic gland polyposis in the stomach | 8/11 (73%) | 13/18 (72%) | 1.00 |

| Duodenal neoplasm | 11/11 (100%) | 14/18 (78%) | .27 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 4/11 (36%) | 6/18 (33%) | 1.00 |

| Gastric adenoma | 9/11 (82%) | – | |

| Gastric cancer | 3/11 (27%) | – | |

| History of multiple gastric neoplasms | 8/11 (73%) | – |

Data on FAP type were unavailable from 4 patients.

Data on familial history of FAP were unavailable from 4 patients.

Data on APC pathogenic variants were unavailable from 10 patients.

Extra-gastrointestinal lesions included desmoid/breast cancer/Barrett’s esophageal cancer/acute lymphocytic leukemia/intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

APC = adenomatous polyposis coli, FAP = familial adenomatous polyposis.

Regarding gastric lesions, 21 patients (72%) had fundic gland polyps, 11 patients (38%) had gastric neoplasms, 9 patients (31%) had gastric adenoma, and 3 patients (10%) had gastric cancer. Multiple gastric neoplasms were observed in 7 patients (24%). Sex, FAP subtypes of, presence or absence of colectomy, family history, APC pathogenic variant, extra-gastrointestinal lesions, fundic gland polyps, duodenal neoplasm, and atrophic gastritis did not differ between patients with and without gastric neoplasms.

3.2. Clinicopathological features of gastric neoplasms

The clinicopathological features of the 32 gastric neoplasm lesions identified in 11 patients are summarized in Table 2. Nine patients had 23 gastric adenoma lesions and 3 patients had 9 gastric cancer lesions. The numbers of gastric lesions per patient are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Comparisons of endoscopic findings between gastric adenoma and gastric cancer.

| Gastric adenoma,n = 23 | Gastric cancer,n = 9 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunophenotype | .032 | ||

| Gastric type | 11 (48%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mixed type | 4 (17%) | 4 (44%) | |

| Intestinal type | 8 (35%) | 5 (56%) | |

| Location, n(%) | 1 | ||

| U or M | 14 (61%) | 5 (56%) | |

| L | 9 (39%) | 4 (44%) | |

| Median neoplasm size, mm(range) | 12 (3–30) | 10 (5–25) | .35 |

| Color, n(%) | <.01 | ||

| Same as background mucosa | 2 (2%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Whitish | 21 (87%) | 1 (11%) | |

| Reddish | 0 (0%) | 6 (67%) | |

| Microscopic type, n(%) | <.01 | ||

| Elevated | 23 (100%) | 1 (11%) | |

| Flat | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Depressed | 0 (0%) | 6 (67%) | |

| Demarcation, n(%) | <.01 | ||

| Clear | 23 (100%) | 1 (11%) | |

| Unclear | 0 (0%) | 8 (89%) | |

| FGPs in surrounding mucosa, n(%) | .011 | ||

| Present | 12 (52%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Absent | 11 (48%) | 9 (100%) | |

| Atrophic gastritis, n (%) | <.01 | ||

| Present | 4 (17%) | 9 (100%) | |

| Absent | 19 (83%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Treatment | |||

| None | 20 (87%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Argon plasma coagulation | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Endoscopic resection | 2 (9%) | 3 (33%) | |

| Surgical resection | 0 (0%) | 6 (67%) |

FGP = fundic gland polyp, L = lower third of the stomach, U or M = upper or middle third of the stomach.

Table 3.

Clinical features and number of gastric neoplasms according to immunophenotype in each patient.

| Case | Sex | Age at colectomy, y | Age at first gastric neoplasms, y | Gastric adenoma,n = 23 | Gastric cancer,n = 9 | H pylori infection status | Atrophic gastritis (Kimura–Takemoto classification) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric phenotype, n | Mixed phenotype, n | Intestinal phenotype, n | Gastric phenotype, n | Mixed phenotype, n | Intestinal phenotype, n | ||||||

| Case 1 | F | 13 | 35 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Unknown | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 2 | F | 40 | 39 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Unknown | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 3 | M | 38 | 39 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Uninfected | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 4 | F | 33 | 39 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Uninfected | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 5 | M | 38 | 43 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Unknown | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 6 | F | 28 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Uninfected | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 7 | M | 41 | 73 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Post- eradication | Present (O-2) |

| Case 8 | M | 32 | 57 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Unknown | Absent (C-0) |

| Case 9 | M | 33 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Infected | Present (C-1) |

| Case 10 | F | 53 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | Infected | Present (O-1) |

| Case 11 | M | 35 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Infected | Present (unclassifiable) |

Among the 23 gastric adenoma lesions, 20 (87%) were followed up without specific treatment, 2 (9%) were endoscopically resected, and 1 (4%) was treated with argon plasma coagulation. Two endoscopically resected lesions and 21 endoscopic biopsy specimens were used for histopathological analysis. Although specific tests for H pylori infection status were not performed in most of the patients with gastric adenoma (Table 3), atrophic gastritis was observed in 4 gastric adenoma lesions (17%), while gastric atrophy was not observed in the other 17 lesions (74%), indicating that three-fourths of adenomas developed in patients without H pylori infection.

Among 9 gastric cancer lesions, 3 were endoscopically resected, while 6 were surgically resected. Although 1 patient had numerous gastric cancers throughout the stomach, only 6 lesions were identifiable on endoscopy before surgery, for which biopsies were performed. Thus, the immunophenotype and endoscopic features of only these 6 lesions were assessed; the other lesions identified on pathological analysis after surgical resection were not evaluated. All gastric cancer lesions were found in the stomachs of patients who were currently infected with H pylori.

Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed that approximately half of the gastric adenomas were classified as gastric phenotype (11/23, 48%), followed by mixed (4/23, 17%), and intestinal (8/23, 35%) phenotypes. In contrast, no gastric cancers were gastric phenotype (0/9, 0%). Five (56%) and 4 (44%) gastric cancer lesions were intestinal and mixed phenotypes, respectively.

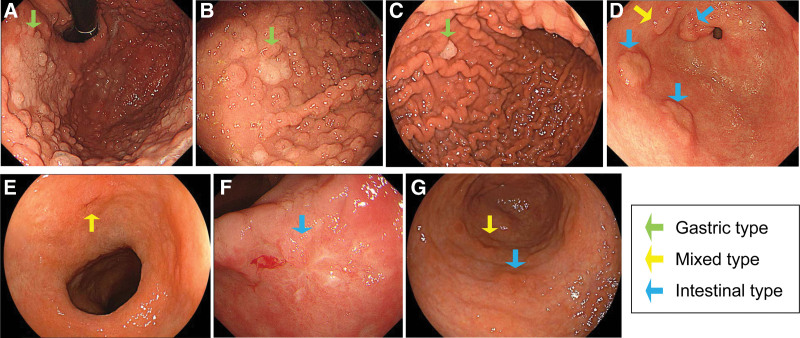

Representative endoscopic images of gastric neoplasms are shown in Figure 1. Gastric adenomas did not differ from gastric cancers in terms of location (U or M region: 14/23. 61% vs 5/9, 56%) or tumor size (median, 12 mm vs 10 mm). In contrast, although some lesions were the same color as the background mucosa in both groups, most gastric adenomas (21/23, 87%) were whitish, whereas two-thirds of gastric cancers (6/9, 67%) were reddish in color (P < .01). Macroscopically, all gastric adenomas were elevated, while two-thirds of gastric cancers (6/9, 67%) were depressed (P < .01). The demarcations between the neoplasms and surrounding normal mucosa were clear in all gastric adenomas but were unclear in most gastric cancers (8/9, 89%) (P < .01). Fundic gland polyps were more frequently observed in the surrounding mucosa of gastric adenomas (12/23, 52%) compared to gastric cancers (0/9, 0%) (P < .01). Conversely, atrophic gastritis was less common in gastric adenomas (4/23, 17%), whereas all gastric cancers were found in the atrophic mucosa (9/9, 100%) (P < .01).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic images of gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP. (A–D) Representative images of gastric adenomas in 4 patients. Whitish elevated lesions with clear demarcations between the neoplasm and surrounding normal mucosa are observed. (A–C) Fundic gland polyps are present in the surrounding mucosa of gastric-type adenomas (green arrows). (D) Atrophic gastritis is absent. One patient had 1-mixed type (yellow arrow) and 3 intestinal-type adenomas (blue arrows) in the lower third of the stomach. (E–G) Representative images of gastric cancers in 3 patients, showing reddish depressed lesions. The demarcations between the neoplasm and surrounding normal mucosa are unclear. Fundic gland polyps are absent in the surrounding mucosa of gastric cancers, while atrophic gastritis is present. Yellow and blue arrows indicate mixed-type and intestinal-type cancers, respectively. FAP = familial adenomatous polyposis.

3.3. Associations of endoscopic features of gastric adenomas and immunophenotype

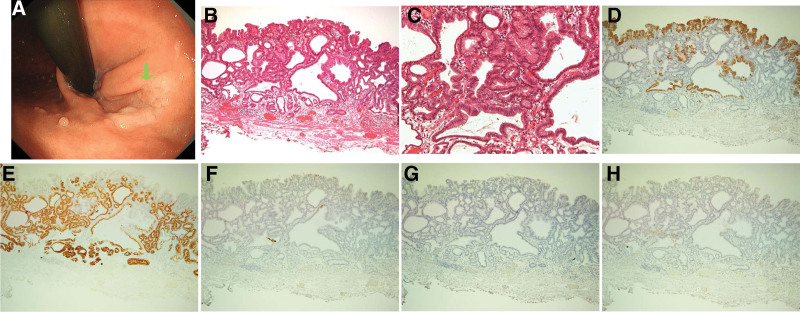

Based on the immunostaining results, we subclassified the gastric adenomas as gastric, mixed, and intestinal types (Figs. 2–4). A comparison of the endoscopic findings of gastric adenomas between the 2 groups is summarized in Table 4. All gastric-type adenomas occurred in the U or M regions and had a “milky-white” color. They predominantly presented a flat elevated morphology (9/11, 82%), with a carpet-like appearance. The other lesions presented as protruded lesions (2/11, 18%) with hemispherical elevations. Fundic gland polyps were found in the surrounding mucosa of all gastric adenomas, whereas no atrophy was observed in the background gastric mucosa. Endoscopic resection was performed in 3 gastric-type adenomas; the remaining 8 lesions were followed up for >1 year. Half of the lesions increased in size, while the other half showed no change in size.

Figure 2.

Images of a gastric-type adenoma. (A) Endoscopic image showing a milky-white and flat elevated lesion in the upper third of the stomach. The green arrow indicates a gastric-type lesion. (B,C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing cystically dilated ducts. (D–H) Adenoma cells immunohistochemically positive for (D) MUC5AC and (E) MUC6 but negative for (F) CDX2, (G) MUC2, and (H) CD10.

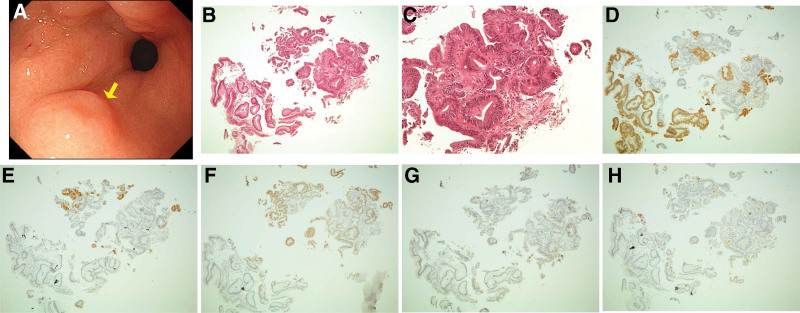

Figure 4.

Images of mixed-type adenomas. (A) Two mixed-type adenomas with the same color as the background mucosa and an elevated morphology with a central depression in the lower third of the stomach. The yellow arrow indicates a mixed-type lesion. (B,C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a biopsy specimen of the lesion, showing tubular structures consisting of tall columnar cells. (D–H) Adenoma cells immunohistochemically positive for (D) MUC5AC, (E) MUC6, (F) CDX2, (G) MUC2, and (H) CD10.

Table 4.

Associations of endoscopic features of gastric adenomas and immunophenotype.

| Gastric type, | Mixed type, | Intestinal type, | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 11 | n = 4 | n = 8 | ||

| Location, n(%) | <.01 | |||

| U or M | 11 (100%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (25%) | |

| L | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 6 (75%) | |

| Median size at the first pathological diagnosis of neoplasm, mm (range) | 12.5 (3–30) | 10.5 (10–12) | 12.5 (10–20) | .89 |

| Observation period, y (range) | 3.1(1–5) | 10 (10) | 10.4 (7–15) | |

| ≧5 mm increase in tumor size, n(%) * |

4/8 (50%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | |

| Color, n(%) | <.01 | |||

| Same as the background mucosa | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Milky-white | 11 (100%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pinkish-white | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 8(100%) | |

| Microscopic type, n(%) | <.01 | |||

| Elevated - flat elevated | 9(82%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Elevated - protruded | 2(18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Elevated - central depression | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 6 (75%) | |

| FGPs in the surrounding mucosa, n(%) | <.01 | |||

| Present | 11 (100%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Absent | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 8 (100%) | |

| Atrophic gastritis, n (%) | .0609 | |||

| Present | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Absent | 11 (100%) | 2 (50%) | 6 (75%) |

* Six lesions with observation periods of <1 year were excluded.

FGP = fundic gland polyp, L = lower third of the stomach, U or M = upper or middle third of the stomach.

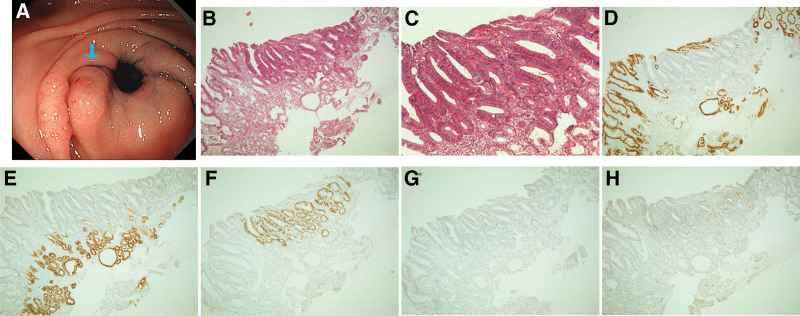

Figure 3.

Images of intestinal-type adenomas. (A) Two pinkish-white lesions with an elevated morphology with a central depression observed in the lower third of the stomach. The blue arrow indicates an intestinal-type lesion. (B,C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a biopsy specimen of the lesion, showing a tubular structure consisting of tall columnar cells. (D–H) Adenoma cells immunohistochemically positive for (F) CDX2, (G) MUC2, and (H) CD10 but negative for (D) MUC5AC and (E) MUC6.

Three-fourths of intestinal-type adenomas were located in the L region (6/8, 75%) and presented as elevations with a central depression (6/8, 75%). All lesions had a pinkish-white color (8/8, 100%). Atrophy was observed in the background mucosa in 1-fourth of the intestinal-type adenomas (2/8, 25%), whereas no fundic gland polyps were observed in the surrounding mucosa in any intestinal-type adenomas (0/8, 0%). None of the intestinal-type adenomas increased in size during the observation period.

One patient (Case 5) simultaneously had 1 mixed-type and 2 gastric-type adenomas. Another patient (Case 8) had 1 mixed-type and 3 intestinal-type adenomas. The endoscopic features of the mixed-type adenomas were like those of gastric-type adenomas in the former patient and intestinal-type adenomas in the latter. In contrast, the other patient had 2 mixed-type adenomas in the pyloric region. These mixed-type adenomas were the same color as the background mucosa, with an elevated morphology accompanying a central depression, which was difficult to endoscopically differentiate from verrucous gastritis. One lesion, similar to an intestinal-type adenoma that could be observed for 10 years, showed no change in size.

3.4. Treatment and prognosis of gastric cancers in patients with FAP

Three patients with FAP in the present study had gastric cancer. One patient (Case 9) underwent endoscopic submucosal resection of gastric cancer in the L region. Histological examination of the resected tissue confirmed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma limited to the mucosal layer, without invasion into the lymphatic and blood vessels. Another patient (Case 10) underwent surgical resection of the stomach. Pathological evaluation of the resected specimen revealed numerous gastric cancers throughout the stomach, as described previously. Histological examination of the resected tissue confirmed well-differentiated adenocarcinoma limited to the mucosal layer without lymph node metastasis. The other patient (Case 11) had 2 gastric cancers in the M region and underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection. One lesion was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosal layer without invasion into the lymphatic and blood vessels; the other lesion was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the submucosal layer and blood vessels. The latter lesion was strictly followed-up without additional surgical resection owing to a previous history of pyloric gastrectomy. No recurrence was noted at 8, 4, or 10 years after resection, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study investigated endoscopic findings of gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP. Based on the immunostaining results, the gastric adenomas included gastric, mixed, or intestinal types. In contrast, gastric cancers showed mixed or intestinal phenotypes, with no gastric-type cancers. Our findings demonstrated that most gastric adenomas presented as whitish elevated lesions in the non-atrophic gastric mucosa regardless of phenotypic classification, while gastric cancers were predominantly reddish, depressed lesions occurring in the atrophic mucosa with current H pylori infection. In patients without FAP, it is well known that gastric adenomas present with a whitish elevated morphology, whereas reddish color and depressed morphology are indicative of gastric cancer rather than gastric adenomas.[21,22] Thus, the endoscopic features of gastric adenomas and cancers in patients with FAP in this study were concordant with the known features of sporadic gastric adenomas and cancers occurring in patients without FAP. Histopathological analysis of mucin phenotypes revealed distinct endoscopic features among the different phenotypes of gastric adenomas. For instance, all gastric-type adenomas occurred in non-atrophic mucosa, in the mucosa where fundic gland polyps exist in the periphery, and in the U or M regions of the stomach and showed milky-white flat elevated or protruded lesions. Meanwhile, the typical endoscopic features of intestinal-type adenomas included occurrence in the L region of the stomach and pinkish-white elevated lesions with a central depression. Although the identification of gastric adenomas, particularly those with a flat elevated morphology that arise in a background of numerous (carpet-like) fundic gland polyps, is sometimes difficult during esophagogastroduodenoscopy,[22] understanding these features will help endoscopists to promptly diagnose gastric-type adenomas in patients with FAP.

Most sporadic gastric adenomas have an intestinal phenotype, and gastric-type adenomas, including foveolar-type adenomas and pyloric gland adenomas, are generally infrequent.[17,18] In contrast, FAP-associated gastric adenomas were mostly gastric-type adenomas, particularly foveolar-type adenomas, in a background of fundic gland polyps, without atrophic gastritis. Intestinal-type adenomas are seen less frequently in FAP patients in Western countries,[23] but are common in Japan.[24] Nakano et al reported that all intestinal-phenotype gastric neoplasms in the stomachs of patients with FAP showed atrophic gastritis,[25] which is common in sporadic cases. In contrast, Shimamoto et al[26] reported that several cases of intestinal-type adenomas were not accompanied by atrophic gastritis.[26] In the present study, although the cases of intestinal-type adenomas were not fully investigated for H pylori infection, none were associated with obvious mucosal atrophy, except for 1 case of mixed-type adenoma. These results suggested that some intestinal-type adenomas in patients with FAP can occur in the gastric mucosa without atrophy.

Previous studies have reported the endoscopic findings of gastric neoplasms with FAP. Shimamoto et al[26] investigated 56 gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP and classified them into 4 types based on location (L: antrum and pylorus, UM: the rest of the stomach) and color (W: white, T: translucent, R: reddish). They reported that 93% of lesions classified as UM-W or UM-T types were gastric phenotypes, while 61% of lesions classified as L type were intestinal or mixed phenotypes. Nakano et al[25] investigated 30 gastric neoplasms, including adenomas and intramucosal carcinomas, in 13 patients with FAP. All gastric neoplasms (10/10, 100%) without atrophic gastritis were whitish, whereas most (13/20, 65%) gastric neoplasms with atrophic gastritis were reddish. In the present study, we further classified whitish color as milky-white and pinkish-white, which corresponded to gastric-type and intestinal-type adenomas, respectively. Although judging the color of gastric neoplasms is a subjective evaluation, these endoscopic findings may be associated with the mucous phenotype and grade of dysplasia and may help in selecting treatment.

In the present study, gastric cancer developed in patients with FAP who were currently infected with H pylori. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed reddish depressed lesions with gastric atrophy. Therefore, endoscopists must be careful not to overlook such lesions, particularly in atrophied gastric mucosa. The development of gastric cancer in patients without FAP is closely associated with H pylori infection, which is common in Asia.[27] H pylori infection reportedly increases the risk of gastric adenoma, a precursor lesion of gastric cancer, in patients with FAP.[6] Similar to sporadic cases, the results of the present study suggest a possible association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer in patients with FAP.

The gastric cancers in this study showed mixed or intestinal phenotypes, with no gastric-type cancers. Previous case reports have described gastric adenocarcinomas arising from fundic gland polyposis[11,28–31] independent of H pylori infection. It is unclear whether gastric adenomas in patients with FAP confer an increased risk of carcinogenesis through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Some reports have suggested the involvement of the colonic adenoma-carcinoma sequence in FAP-associated gastric carcinogenesis.[13,31] In the present study, among 12 gastric adenomas associated with fundic gland polyposis, 4 (33%) increased in size during the observation period. Therefore, it is important to select an appropriate treatment strategy that considers the possibility of carcinogenesis.

The long-term outcomes of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP and their optimal management have not been fully elucidated. Iida et al investigated gastric adenomas in 13 patients with FAP or Gardner syndrome who were followed up for a mean of 6.8 years.[13] During the follow-up period, gastric adenomas newly appeared in 6 patients, while the remaining 7 patients showed no distinct changes in the number, size, and histologic features. Recent research in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands revealed that adenomas with high-grade dysplasia were significantly larger than adenomas with low-grade dysplasia (median size, 25 mm vs 6 mm).[8] The research group has proposed a new framework for the management of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP, which recommends endoscopic mucosal resection for lesions measuring 5–20 mm and endoscopic submucosal dissection for lesions measuring > 20 mm. However, only two-thirds of the patients (63/104 patients, 61%) underwent gastric adenoma excision or ablation in actual clinical settings.

The results of the present study revealed that half of the gastric-type adenomas increased in size by ≥ 5 mm (4/8, 50%). Thus, we believe that gastric-type adenomas should be endoscopically resected irrespective of tumor size, considering their growth potential. Meanwhile, none of the intestinal-type (0/8, 0%) or mixed-type (0/1, 0%) lesions increased in size over at least 7 years of observation. Abraham et al[17] classified gastric adenomas as intestinal-type, containing at least focal goblet cells and/or Paneth cells, and gastric foveolar type, lined entirely by gastric mucin cells, as shown by periodic acid-Schiff/Alcian blue staining. Intestinal-type adenomas were significantly more likely than gastric foveolar–type adenomas (including those in patients with FAP) to show high-grade dysplasia, adenocarcinoma within the polyp, intestinal metaplasia in the surrounding stomach, and gastritis. Although the method of classification using morphological criteria differs from that of the present study, which performed immunolabeling for mucins, the intestinal-type adenomas in the present study were not associated with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, and their malignant potential may be related to H pylori infection and atrophic gastritis. Although follow-up without resection may be acceptable in intestinal-type adenomas measuring ≤ 20 mm without atrophic gastritis since they did not increase in size in this study, this concept requires further investigations with larger sample sizes and longer observation periods. Overall, we believe that the management of adenomas based on phenotypic variations is preferred, considering their differences in biological behavior.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution. The second limitation is the small number of participants. Third, as mentioned previously, H pylori infection status was not available for some enrolled patients. Fourth, the follow-up period was relatively short to estimate the risk of cancer emerging in adenomas. Therefore, further research with a larger number of patients and a longer follow-up period is needed to determine the true nature of gastric adenomas in patients with FAP. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the endoscopic findings of gastric adenomas and gastric cancers in patients with FAP and to examine the differences in endoscopic findings and changes in size over time of gastric adenomas in terms of mucous phenotypes. Fifth, pictures taken during the esophagogastroduodenoscopy examination were operator-dependent. Moreover, interpretation of endoscopic images is essentially subjective. We believe that establishment of subcategorization methods for gastric neoplasms in patients with FAP based on the phenotypic variations and grades of dysplasia would enable more objective evaluation of these lesions.

In conclusion, this study investigated gastric adenomas and cancers in patients with FAP. Detailed analysis according to phenotypic variations revealed that gastric-type adenomas occurred in the non-atrophic mucosa of the U or M regions, accompanied by fundic gland polyps. These adenomas presented as milky-white flat elevated or protruded lesions. Most intestinal-type adenomas were pinkish-white, occurred in the L region, and presented as elevated lesions with a central depression. Gastric cancers present as reddish, depressed lesions with gastric atrophy. We believe that understanding these endoscopic features will enable the prompt diagnosis and appropriate management of gastric lesions in patients with FAP.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Mayu Kobashi, Masaya Iwamuro, Hiroyuki Okada.

Data curation: Sakiko Kuraoka, Shoko Inoo, Shotaro Okanoue, Takuya Satomi, Kenta Hamada, Makoto Abe, Yoshiyasu Kono, Yoshimitsu Kanzaki, Seiji Kawano, Yoshiro Kawahara.

Formal analysis: Mayu Kobashi, Masaya Iwamuro, Takehiro Tanaka.

Supervision: Masaya Iwamuro, Hiroyuki Okada.

Writing – original draft: Mayu Kobashi.

Abbreviations:

- APC =

- adenomatous polyposis coli

- FAP =

- familial adenomatous polyposis

- H. pylori =

- Helicobacter pylori

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patients were prospectively registered and analyzed in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Okayama University Hospital. (Registry No: 2004-013)

How to cite this article: Kobashi M, Iwamuro M, Kuraoka S, Inoo S, Okanoue S, Satomi T, Hamada K, Abe M, Kono Y, Kanzaki H, Kawano S, Tanaka T, Kawahara Y, Okada H. Endoscopic findings of gastric neoplasms in familial adenomatous polyposis are associated with the phenotypic variations and grades of dysplasia. Medicine 2022;101:41(e30997).

Contributor Information

Masaya Iwamuro, Email: iwamuromasaya@yahoo.co.jp.

Sakiko Kuraoka, Email: purewhite_wolf@yahoo.co.jp.

Shoko Inoo, Email: auldlangsyne0219@yahoo.co.jp.

Shotaro Okanoue, Email: shotaro.bc.19@gmail.com.

Takuya Satomi, Email: tak_03_01_stm@yahoo.co.jp.

Kenta Hamada, Email: paosishou@yahoo.co.jp.

Makoto Abe, Email: makotabe7@gmail.com.

Yoshiyasu Kono, Email: hxnwq178@yahoo.co.jp.

Hiromitsu Kanzaki, Email: kanzaki@qc4.so-net.ne.jp.

Seiji Kawano, Email: skawano@mpd.biglobe.ne.jp.

Takehiro Tanaka, Email: takehiro@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Yoshiro Kawahara, Email: yoshirok@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Okada, Email: hiro@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

References

- [1].Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bussey HJ. Familial polyposis coli. Pathol Annu. 1979;14(Pt 1):61–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Novelli M. The pathology of hereditary polyposis syndromes. Histopathology. 2015;66:78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Iwama T, Tamura K, Morita T, et al. A clinical overview of familial adenomatous polyposis derived from the database of the Polyposis Registry of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yamaguchi T, Ishida H, Ueno H, et al. Upper gastrointestinal tumours in Japanese familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:310–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Kobori Y, et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection and mucosal atrophy on gastric lesions in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2002;51:485–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sarre RG, Frost AG, Jagelman DG, et al. Gastric and duodenal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis: a prospective study of the nature and prevalence of upper gastrointestinal polyps. Gut. 1987;28:306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Martin I, Roos VH, Anele C, et al. Gastric adenomas and their management in familial adenomatous polyposis. Endoscopy. 2021;53:795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shibata C, Ogawa H, Miura K, et al. Clinical characteristics of gastric cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jagelman DG, DeCosse JJ, Bussey HJ. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1988;1:1149–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mankaney G, Leone P, Cruise M, et al. Gastric cancer in FAP: a concerning rise in incidence. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Walton SJ, Frayling IM, Clark SK, et al. Gastric tumours in FAP. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iida M, Yao T, Itoh H, et al. Natural history of gastric adenomas in patients with familial adenomatosis coli/Gardner’s syndrome. Cancer. 1988;61:605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Abraham SC, Park SJ, Lee JH, et al. Genetic alterations in gastric adenomas of intestinal and foveolar phenotypes. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:786–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vieth M, Kushima R, Borchard F, et al. Pyloric gland adenoma: a clinico-pathological analysis of 90 cases. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bertz S, Angeloni M, Drgac J, et al. Helicobacter infection and gastric adenoma. Microorganisms. 2021;9:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, et al. Gastric adenomas: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pezhouh MK, Park JY. Gastric pyloric gland adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:823–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Valente P, Garrido M, Gullo I, et al. Epithelial dysplasia of the stomach with gastric immunophenotype shows features of biological aggressiveness. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tsukashita S, Kushima R, Bamba M, et al. MUC gene expression and histogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ngamruengphong S, Boardman LA, Heigh RI, et al. Gastric adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis are common, but subtle, and have a benign course. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2014;12:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wood LD, Salaria SN, Cruise MW, et al. Upper GI tract lesions in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): enrichment of pyloric gland adenomas and other gastric and duodenal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Komoto K, Haruma K, Kamada T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric neoplasia: correlations with histological gastritis and tumor histology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nakano K, Kawachi H, Chino A, et al. Phenotypic variations of gastric neoplasms in familial adenomatous polyposis are associated with endoscopic status of atrophic gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shimamoto Y, Ishiguro S, Takeuchi Y, et al. Gastric neoplasms in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: endoscopic and clinicopathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:1030–1042.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Leone PJ, Mankaney G, Sarvapelli S, et al. Endoscopic and histologic features associated with gastric cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:961–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Garrean S, Hering J, Saied A, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma arising from fundic gland polyps in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome. Am Surg. 2008;74:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hofgärtner WT, Thorp M, Ramus MW, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma associated with fundic gland polyps in a patient with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tanabe H, Moriichi K, Takahashi K, et al. Genetic alteration of colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence among gastric adenocarcinoma and dysplastic lesions in a patient with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]