Abstract

The performances of the MRL dengue fever virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the PanBio Dengue Duo IgM capture and IgG capture ELISA were compared. Eighty sera from patients with dengue virus infections, 24 sera from patients with Japanese encephalitis (JE), and 78 sera from patients with nonflavivirus infections, such as malaria, typhoid, leptospirosis, and scrub typhus, were used. The MRL test showed superior sensitivity for dengue virus infections (94 versus 89%), while the PanBio test showed superior specificity for JE (79 versus 25%) and other infections (100 versus 91%). The PanBio ELISA showed better overall performance, as assessed by the sum of sensitivity and specificity (F value). When dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections were compared, F values of 189 and 185 were obtained for the PanBio and MRL tests, respectively, while when dengue virus infections and JE were compared, F values of 168 and 119 were obtained. The results obtained with individual sera in the PanBio and MRL IgM ELISAs showed good correlation, but this analysis revealed that the cutoff value of the MRL test was set well below that of the PanBio test. Comparing the sensitivity and specificity of the tests at different cutoff values (receiver-operator analysis) revealed that the MRL and PanBio IgM ELISAs performed similarly in distinguishing dengue virus from nonflavivirus infections, although the PanBio IgM ELISA showed significantly better distinction between dengue virus infections and JE. The implications of these findings for the laboratory diagnosis of dengue are discussed.

Dengue is an important arboviral disease, with millions of cases occurring each year (9, 25). It presents as either dengue fever (a self-limiting flu-like illness with very low mortality) or dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) (characterized by increased vascular permeability, thrombocytopenia, and hemorrhagic manifestations). Primary infection with one of the four dengue virus serotypes confers lasting immunity to that serotype, while secondary infection with a different serotype is associated with an increased risk of DHF, which has a mortality rate of 10% if untreated (11, 12).

Other flaviviruses, such as Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus and Chikunguya virus, cocirculate with dengue virus in southern Asia and eastern Asia. JE is a major public health problem in Asia, with approximately 35,000 cases and 10,000 deaths occurring annually throughout Asia (16). The case fatality rate of JE virus infections is approximately 25%, with 50% of survivors developing permanent neurological and psychiatric sequelae (13). Most people in areas of endemicity have been exposed to at least two flavivirus infections during early childhood, and the majority of cases are asymptomatic. This situation makes definitive diagnosis difficult due to the cross-reactive antibodies produced during these infections (23). Although dengue and JE can be distinguished on clinical grounds, most laboratories depend on serological diagnosis to confirm dengue virus infections (20, 33). Traditionally, the hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay has been used as the gold-standard serological test, but the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has been proposed as a simpler and more rapid alternative (10).

Primary and secondary dengue virus infections show markedly different immunological responses (14). Primary infections are characterized by an increase in the levels of dengue virus-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) 3 to 5 days after the onset of infection, and this increase is generally detectable for 30 to 90 days. IgG levels increase after IgM levels to a modest degree. In secondary dengue virus infections, the IgM response can be slower, weaker, and short-lived, and some patients do not show a detectable IgM response (17, 27, 30, 33). However, IgG levels increase rapidly to values higher than those observed in primary or past dengue virus infections and remain at these values for 30 to 40 days (10, 14).

Two strategies have been commonly used for the serological diagnosis of dengue virus infections by ELISA. Many laboratories rely on the IgM capture ELISA to diagnose both primary and secondary infections (1–3, 5, 7, 19, 21, 33, 35), while others have used a combination of IgM capture and IgG capture ELISAs (6, 17, 18, 22, 27–32). In the latter method, the cutoff value of the IgG ELISA is generally set to discriminate between the high levels of IgG characteristic of secondary dengue virus infections and the lower IgG levels characteristic of primary or past dengue virus infections. With this combination, the majority of secondary dengue virus infections are detected on the basis of IgG, and most of these also show an elevation of IgM, while the majority of primary dengue virus infections show an elevation of IgM but not IgG. Quantitation of antidengue IgG in these tests also allows a distinction between primary and secondary dengue virus infections (6, 17, 18, 22, 27–32).

Recently, two commercial ELISAs that are based on these different strategies have been released: the MRL dengue fever virus IgM capture ELISA (MRL Diagnostics, Cypress, Calif.) and the PanBio Dengue Duo IgM capture and IgG capture ELISA (PanBio Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia). The MRL ELISA detects only IgM for the diagnosis of active infection, while the PanBio ELISA relies on both IgM and IgG detection to diagnose active dengue virus infection. The IgG cutoff value in the PanBio ELISA is set to detect the high levels of IgG characteristic of secondary but not primary or past infections, and the ELISA has shown an excellent correlation with the HAI assay (22, 29, 32). The PanBio ELISA has been shown to have a sensitivity similar to that of the in-house reference ELISA at the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS), which also uses the combination of IgM and IgG for diagnosis (32). An indirect IgG ELISA is also available from MRL, but this assay is less useful for the diagnosis of acute dengue virus infection with single sera, as the lower cutoff value and format of this assay detect IgG from past as well as current dengue virus infections. In this study, the performances of the MRL and PanBio ELISAs were compared by use of sera taken from patients with primary and secondary dengue virus infections, JE, and nonflavivirus infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case definitions for dengue and JE.

In children experiencing a febrile illness consistent with dengue fever or DHF, dengue virus infections were defined as the isolation of a dengue virus, the detection of IgM to dengue virus (as opposed to IgM to JE virus), or a sustained elevation (≥1:2,560) or a fourfold increase in the dengue virus HAI antibody titer (17, 31). JE was defined as a febrile illness associated with a decrease in consciousness and the presence of IgM to JE virus in the cerebrospinal fluid. Dengue virus infection was categorized as primary or secondary according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (titer of ≥1:2,560 in a single serum sample taken as secondary dengue) and the standard operating procedure for the reference enzyme immunoassay (17, 34).

Serum samples.

Serum from patients with a suspected dengue virus infection was collected at the time of admission to the hospital and at discharge at either the Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health (Bangkok Children’s Hospital), Bangkok, Thailand, or the Kamphaeng Phet Provincial Hospital, Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand, and frozen at −70°C prior to the assay. Paired sera from 40 patients with dengue (20 primary and 20 secondary infections) were used in this study, as were single serum sample from 20 patients with suspected dengue but no laboratory evidence of dengue (NEI). Acute-phase sera from patients with dengue were collected between 1 and 11 days after the onset of symptoms (mean, 5 days), while the interval between the collection of the first and second serum samples ranged from 1 to 8 days (mean, 2.9 days). All patients with dengue virus infections were children or teenagers (16 female and 24 male). Patients with primary dengue were between 1.0 and 10.8 years old (mean, 5.5 years), while patients with secondary dengue were between 3.4 and 19.8 years old (mean, 9 years). Virus isolation or reverse transcription-PCR revealed the serotype for 20 of the dengue virus infections. In primary infections, four were dengue virus type 1 (dengue-1), seven were dengue-2, and one was dengue-3, while in secondary infections, two were dengue-1, three were dengue-2, and three were dengue-3. Paired sera from 12 patients with JE were collected from the Center for Tropical Diseases, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The interval between the collection of the first and second serum samples ranged from 3 to 11 days (mean, 7 days). A panel of serum samples from nonflavivirus infections was also included. These represented Widal felix test-positive cases of typhoid from Malaysia (n = 15), indirect immunoperoxidase test-positive cases of scrub typhus from Thailand (n = 15), microscopic agglutination test-positive cases of leptospirosis from Australia (n = 15), and blood smear-positive cases of malaria from Papua New Guinea (n = 13). Both MRL and PanBio ELISAs were performed at PanBio.

PanBio Dengue Duo ELISA.

The PanBio ELISA (product code DEC-400) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two microtiter plates were supplied, one containing stabilized dengue-1 through dengue-4 (antigen plate) and the other containing either anti-human IgM or anti-human IgG bound to separate wells (assay plate). Peroxidase-labeled anti-dengue virus monoclonal antibody (125 μl/well) was added to the antigen plate to solubilize the antigens and form antibody-antigen complexes. Concurrently, 100 μl of patient serum, diluted 1:100 in the diluent provided, was added to each well of the assay plate containing either bound anti-human IgM or bound anti-human IgG, and human IgM or IgG in the patient’s serum was captured. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature (antigen plate) or 37°C (assay plate); then, the assay plate was washed, and 100 μl of antibody-antigen complexes per well was transferred from the antigen plate to the assay plate. These complexes were captured by dengue virus-specific IgM or IgG during incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The plate was washed, and bound complexes were visualized through the addition of 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate per well. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 1 M phosphoric acid per well, and the strips were read at 450 nm with a microtiter plate reader. Positivity was determined by comparison to the IgM and IgG reference sera provided (cutoff calibrators). A positive sample was defined as having a sample/calibrator absorbance ratio of ≥1.0, and a negative sample was defined as having a ratio of <1.0. Dengue virus infection was characterized by the elevation of either IgM or IgG, with a negative sample being defined as having both IgM and IgG ratios of <1.0. The cutoff value in the IgG ELISA represented a level used to distinguish secondary dengue virus infections from primary or past dengue virus infections, according to WHO classification by the HAI assay (34).

MRL dengue fever virus IgM capture ELISA.

The MRL ELISA (product code EL1500M) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions by use of the recommended classical Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocol. After rehydration of the anti-human IgM-coated microtiter plate with wash buffer for 5 min, 100 μl of patient serum diluted 1:101 was added to each well and incubated for 60 min at room temperature (23°C). After the plate was washed three times with the buffer provided, 100 μl of inactivated dengue-1 through dengue-4 was added to each well, and the plate was incubated overnight at 4°C. The antigens were provided in lyophilized form and prepared directly before use by reconstitution with the solution provided. The plate was washed as described above, and 100 μl of conjugate solution (peroxidase-conjugated mouse antiflavivirus antibody) was added to each well for 30 min at room temperature before another wash and the addition of 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine substrate per well. After 10 min at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of stop reagent (1 M sulfuric acid) per well, and the optical density at 450 nm was read with a microtiter plate reader. Positivity was determined by comparison to the IgM cutoff calibrator serum provided. A positive sample was defined as having a sample/calibrator absorbance ratio of ≥1.0, and a negative sample was defined as having a ratio of <1.0.

Data analysis.

The proportion of patients with antibody levels above the designated cutoff value for the ELISA was determined. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare sensitivity, specificity, and F values. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to compare ELISA ratios in individual sera. Receiver-operator curve (ROC) analysis was performed to compare sensitivity and specificity at different cutoff values (24). The cutoff value for optimal assay performance was determined with a two-curve ROC analysis (TC-ROC) (8, 36). Statistics were determined by use of Instat (Graphpad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Assay sensitivity for dengue virus infections.

The sensitivities obtained with the assays for sera from dengue patients are summarized in Table 1. The MRL and PanBio ELISAs each detected all 40 cases of dengue when paired sera were used (either S1 [admission] or S2 [discharge] positive). For the admission (S1) sera, the MRL ELISA detected 17 of 20 primary infections and 19 of 20 secondary infections (IgM positive), and the PanBio ELISA detected 16 of 20 primary infections and 15 of 20 secondary infections (either IgM or IgG positive). For the discharge (S2) sera, the MRL ELISA detected 19 of 20 primary infections and 20 of 20 secondary infections, while the PanBio ELISA detected all 40 dengue virus infections. Consequently, the MRL ELISA detected 36 of 40 sera (90%) from primary infections and 39 of 40 sera (98%) from secondary infections, and the PanBio ELISA detected 36 of 40 sera (90%) from primary infections and 35 of 40 sera (88%) from secondary infections. The overall sensitivities for dengue virus infections were 75 of 80 (94%) in the MRL ELISA and 71 of 80 (89%) in the PanBio ELISA. These values were not significantly different (P, 0.4022).

TABLE 1.

Sensitivities of ELISAs for primary and secondary dengue virus infections

| Test | No. of positive serum samples/total no.

tested (% sensitivity) for the following dengue category:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary

|

Secondary

|

All

|

||||||||||

| S1 | S2 | S1 or S2 | Total | S1 | S2 | S1 or S2 | Total | S1 | S2 | S1 or S2 | Total | |

| MRL IgM | 17/20 (85%) | 19/20 (95%) | 20/20 (100%) | 36/40 (90%) | 19/20 (95%) | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) | 39/40 (98%) | 36/40 (90%) | 39/40 (98%) | 40/40 (100%) | 75/80 (94%) |

| PanBio IgM | 16/20 (80%) | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) | 36/40 (90%) | 7/20 (35%) | 16/20 (80%) | 16/20 (80%) | 23/40 (58%) | 23/40 (58%) | 36/40 (90%) | 36/40 (90%) | 59/80 (74%) |

| PanBio IgM and IgG | 16/20 (80%) | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) | 36/40 (90%) | 15/20 (75%) | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) | 35/40 (88%) | 31/40 (78%) | 40/40 (100%) | 40/40 (100%) | 71/80 (89%) |

S1, admission sera; S2, discharge sera.

Assay specificity for JE virus infections.

The specificities of the ELISAs for JE virus infections are shown in Table 2. For the admission (S1) sera, the MRL ELISA showed a false-positive elevation for 9 of 12 JE virus infections (75%) (IgM positive), and the PanBio ELISA was positive for 2 of 12 infections (17%) (either IgM or IgG positive). For the discharge (S2) sera, the MRL ELISA showed a false-positive elevation for 9 of 12 JE virus infections (75%) (IgM positive), and the PanBio ELISA was positive for 3 of 12 infections (25%). Consequently, the overall specificities of the assays for JE virus infection were 6 of 24 (25%) in the MRL ELISA and 19 of 24 (79%) in the PanBio ELISA. These values were significantly different (P, 0.0004). When paired sera were used for diagnosis (either S1 or S2 levels above the cutoff), the specificity of the MRL ELISA was only 17% (IgM positive), and the PanBio ELISA showed a 75% specificity (IgM or IgG positive) (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Specificities of dengue ELISAs for JE virus and nonflavivirus infections

| Test | No. of negative serum samples/total no.

tested (% specificity) for the following infection:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JE S1 | JE S2 | JE total | NEI | Scrub typhus | Leptospirosis | Typhoid | Malaria | Nonflavivirus total | Non-dengue virus total | |

| MRL IgM | 3/12 (25%) | 3/12 (25%) | 6/24 (25%) | 17/20 (85%) | 14/15 (93%) | 14/15 (93%) | 14/15 (93%) | 12/13 (92%) | 71/78 (91%) | 77/102 (75%) |

| PanBio IgM | 12/12 (100%) | 12/12 (100%) | 24/24 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 13/13 (100%) | 78/78 (100%) | 102/102 (100%) |

| PanBio IgM and IgG | 10/12 (83%) | 9/12 (75%) | 19/24 (79%) | 20/20 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 13/13 (100%) | 78/78 (100%) | 97/102 (95%) |

NEI, patients with clinically suspected dengue but no laboratory evidence of infection.

Assay specificity for nonflavivirus infections.

All 78 sera collected from patients with nonflavivirus infections, including those with scrub typhus, malaria, leptospirosis, and typhoid, were negative in the PanBio ELISA (both IgM and IgG negative). In contrast, the MRL IgM ELISA was positive for sera from 3 of 20 patients with NEI (15%), 1 of 15 with scrub typhus (7%), 1 of 15 with leptospirosis (7%), 1 of 15 with typhoid (7%), and 1 of 13 with malaria (8%) (Table 2). Overall, the PanBio ELISA showed significantly higher specificity than the MRL ELISA for these sera (100 versus 91%; P, 0.0136).

Overall performance of ELISAs.

The overall performance of the PanBio and MRL ELISAs was assessed by the sum of sensitivity and specificity (F value) (Table 3). The PanBio IgM ELISA (F, 174) showed a performance similar to that of the MRL IgM ELISA (F, 169) (P, 0.5675) when dengue and all other infections were analyzed. However, the additional use of IgG in the PanBio ELISA resulted in performance superior to that obtained with IgM alone (F, 184 versus 169; P, 0.0289).

TABLE 3.

ELISA performance

| Test |

F valuea

for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue virus and JE virus | Dengue virus and nonflavivirus | Dengue virus and non-dengue virus | |

| MRL IgM | 119 | 185 | 169 |

| PanBio IgM | 174 | 174 | 174 |

| PanBio IgM and IgG | 168 | 189 | 184 |

The F value represents the sum of sensitivity and specificity.

A major cause of the poorer performance of the MRL IgM ELISA was the high cross-reactivity observed in JE virus infections. When the dengue and JE groups were analyzed, the MRL IgM ELISA showed an F value of only 119, while the PanBio IgM ELISA showed a significantly higher F value, 174 (P, <0.0001). The additional use of IgG in the PanBio ELISA decreased the F value to 168 due to the cross-reactivity observed with JE at the IgG level, although this assay was still superior to the MRL ELISA (F, 119) (P, <0.0001). The PanBio ELISA (F, 189) showed a performance similar to that of the MRL ELISA (F, 185) when only dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections were analyzed (P, 0.5437).

Correlation analysis.

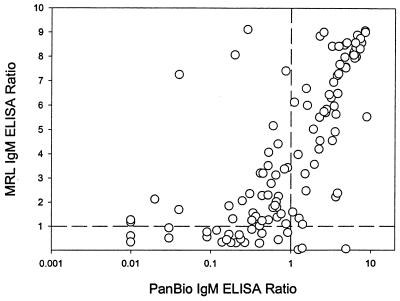

The values obtained in the PanBio and MRL IgM ELISAs for individual sera correlated well (r, 0.7805; P, <0.0001; Fig. 1). The cutoff value used in the MRL IgM ELISA was lower than that used in the PanBio ELISA, as indicated by the fact that the intersection of the cutoff lines used in the different assays was below the majority of the data points on the correlation graph.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of individual assay values obtained in the MRL and PanBio IgM capture ELISAs. The cutoff ratios are shown as broken lines.

ROC analysis.

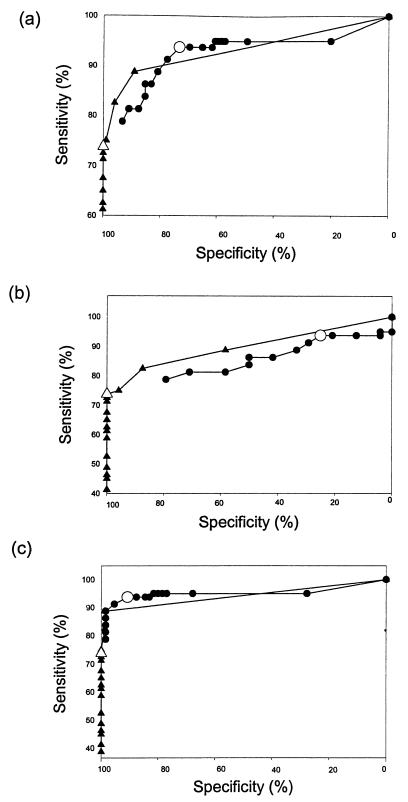

The MRL and PanBio IgM ELISAs were compared by ROC analysis (Fig. 2). The PanBio IgM ELISA showed superior performance when the sensitivity for dengue virus infections and the specificity for non-dengue virus infections at different cutoff values were compared (Fig. 2a). The difference observed between the PanBio and MRL IgM ELISAs in ROC analysis was due to the much lower specificity observed with the MRL ELISA for patients with JE (Fig. 2b and Table 2). The PanBio test showed specificity superior to that of the MRL test regardless of sensitivity (Fig. 2b). Consequently, there was no difference between the PanBio and MRL IgM ELISAs when dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections were compared (Fig. 2c).

FIG. 2.

ROC analysis. Sensitivity and specificity for the MRL IgM capture ELISA (circles) and the PanBio IgM capture ELISA (triangles) were determined over a range of cutoff values. Comparisons were performed between dengue virus and non-dengue virus infections (a), dengue virus and JE virus infections (b), and dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections (c). The sensitivity and specificity at the cutoff values recommended by the manufacturers are shown by larger symbols.

TC-ROC analysis.

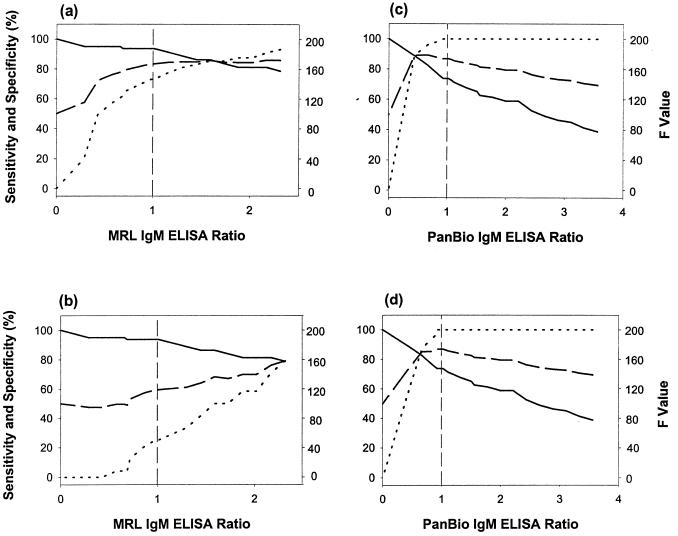

TC-ROC analysis was used to determine the cutoff value that maximized the combined sensitivity and specificity (F value) of the tests. This value occurs where the sensitivity and specificity lines intersect in the TC-ROC analysis. A comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and overall performance (F value) at different cutoff values revealed that the cutoff in the MRL IgM ELISA was set below the value needed to maximize diagnostic performance (F value) for dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections (Fig. 3a) and dengue virus and JE virus infections (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the cutoff in the PanBio IgM ELISA was set above the level needed to provide maximal distinction between dengue virus infections and both nonflavivirus and JE virus infections (Fig. 3c and d).

FIG. 3.

TC-ROC analysis. Sensitivity (solid curve), specificity (dotted curve), and F value (broken curve) were determined over a range of cutoff values. Comparisons were performed between dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections in the MRL IgM ELISA (a), dengue virus and JE virus infections in the MRL IgM ELISA (b), dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections in the PanBio IgM ELISA (c), and dengue virus and JE virus infections in the PanBio IgM ELISA (d). The cutoff ratio (1.0) is shown as a broken vertical line.

DISCUSSION

A number of commercially available ELISAs for the serological diagnosis of dengue virus infections have recently been described (3, 21, 22, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35). All of these tests have been reported to have good sensitivity and specificity, but they use different diagnostic strategies or assay formats. Therefore, a comparison of their sensitivity and specificity with the same sera is necessary to validate their performance. In this study, the PanBio Dengue Duo IgM capture and IgG capture ELISA and the MRL dengue fever virus IgM capture ELISA were compared by use of characterized sera from patients with dengue virus, JE virus, and nonflavivirus infections.

The MRL ELISA uses only IgM for the diagnosis of active dengue infection, and this strategy has been described in a number of studies (1–3, 5, 7, 21, 33, 35). MRL also produces a dengue IgG ELISA, but this test is of little use in the diagnosis of active dengue, since the cutoff value is set to detect past as well as active infections. For example, the MRL dengue IgG ELISA was positive for 47 of 102 sera from non-dengue virus infections used in this study (46%) (data not shown). IgM is the marker of choice in primary dengue, but patients with secondary dengue have been reported to show a slower production of IgM that may be short-lived, and about 5% of patients have undetectable levels of IgM (14, 27, 33). To overcome this problem, the cutoff value of the IgM ELISA needs to be lower, but then false-positive reactivity with other infections may occur. This situation proved to be the case in the data presented here, where the MRL IgM ELISA showed a significantly higher sensitivity for dengue infections than the PanBio IgM ELISA (94 verses 74%; P, <0.0001) but the MRL IgM ELISA showed a significantly lower specificity than the PanBio IgM ELISA (75 verses 100%; P, <0.0001). The specificity of the MRL IgM ELISA was significantly lower than that of the PanBio IgM ELISA for nonflavivirus infections (91 verses 100%; P, 0.0136) and was particularly low for JE virus infections (25 verses 100%; P, <0.0001). High cross-reactivity with JE virus has also been reported for another commercially available IgM test (19).

Analysis revealed that despite the good correlation between the individual results of the PanBio and MRL IgM assays, the differences observed in sensitivity and specificity were due to differences in the cutoff values used in these assays (the PanBio cutoff value was much higher). A comparison of the individual assay values for sera that were positive in both ELISAs revealed that, on average, the ratio of sample OD to cutoff OD in the MRL test was 6.1 times higher than that in the PanBio test (data not shown), indicating that the cutoff in the MRL test was 6.1 times lower than that in the PanBio test. This fact was also evident in the ROC analysis, where the MRL and PanBio IgM ELISAs showed the same relationship between sensitivity and specificity for dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections, but the cutoff value of the MRL assay was set at a much lower level, leading to higher sensitivity and lower specificity. In contrast was the result observed when dengue virus and JE virus infections were compared in an ROC analysis. In this case, the PanBio IgM ELISA had specificity superior to that of the MRL IgM ELISA at all sensitivities tested.

Apart from the differences in cutoff values, the discrepancy observed in JE virus infections may have been due to the contrasting incubation times and procedures used in the two tests. In the MRL IgM ELISA, antigen was incubated overnight with captured IgM, while in the PanBio IgM ELISA, antigen was incubated for only 1 h with captured IgM. It is possible that the longer incubation time used in the MRL test led to the capture of dengue virus antigen by lower-affinity IgM produced during JE virus infection. Similar results have been observed with “shotgun” neutralization tests that use incubation times shorter than those of the standard procedure (15). Alternatively, differences in the timing of conjugate addition in the two assays may have affected the binding of dengue virus antigen to anti-JE virus IgM. That is, in the MRL test, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated monoclonal antibody was added after the binding of antigen by captured IgM, while in the PanBio test, dengue virus antigen and conjugate were complexed before incubation in the capture plate. The latter method has been reported previously to halve the number of incubation steps required in a dengue IgM capture ELISA without affecting the correlation of the assay with the HAI assay (4).

The PanBio ELISA uses both IgM capture and IgG capture for the diagnosis of active dengue virus infection, and the value of this strategy has been reported in a number of studies (6, 17, 18, 26–32). The strategy of using IgG as well as IgM is based on the high level of IgG that increases rapidly in secondary dengue and remains elevated for 30 to 40 days before returning to the levels observed in primary and past dengue (10, 14). This fact is the basis of the WHO criteria for the classification of primary and secondary dengue, with acute or recent secondary infections being characterized by a high HAI titer (≥1:2,560) in a single serum sample (34). The use of IgG overcomes the need to detect the low levels of IgM seen in some patients with secondary dengue and allows a distinction between primary and secondary dengue (6, 17, 18, 28–32). In this study, the PanBio IgM ELISA detected all cases of primary dengue and 80% of secondary infections in paired sera, while the PanBio IgG ELISA detected all cases of secondary dengue and only 20% of primary infections in paired sera (data not shown). Consequently, the combined use of IgM and IgG led to the detection of all dengue cases when paired sera were used. The overall sensitivity of the combination of IgG and IgM for individual sera in the PanBio ELISA was not significantly different from that observed in the MRL ELISA (89 verses 94%; P, 0.5645). However, the specificity of the PanBio ELISA was significantly higher (95 verses 75%; P, <0.0001), primarily due to the superior specificity with JE sera (79 verses 25%; P, <0.0001). The PanBio test also showed significantly higher specificity for nonflavivirus infections (100 verses 91%; P, 0.0136). In the PanBio ELISA, all cross-reactivity with JE sera was observed at the IgG and not the IgM level, as reported previously in other studies (23, 32).

The inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity has been documented (8, 24, 36). Consequently, manufacturers of commercially available assays need to set cutoff values so as to maximize sensitivity and/or specificity, depending on the target disease. One method that has been suggested regarding cutoff determination is to maximize the combined sensitivity and specificity (F value); the F value occurs at the intersection of sensitivity and specificity graphs in a TC-ROC analysis (8, 36). In this study, the PanBio ELISA showed the best performance (highest F value) in distinguishing between dengue virus and non-dengue virus infections, and the F value was significantly higher than the F value obtained with the MRL ELISA (P, 0.0289). TC-ROC analysis revealed that this result was primarily due to differences in cutoff selection in the respective IgM capture ELISAs. The MRL IgM ELISA used a much lower cutoff value than the PanBio IgM ELISA in order to detect secondary dengue cases that showed lower IgM levels (data not shown), while the PanBio IgM ELISA used a higher cutoff value and relied primarily on an IgG ELISA to detect secondary dengue cases. This strategy also eliminated cross-reactivity with JE and other infections in the PanBio IgM ELISA. TC-ROC analysis revealed that the cutoff value of the MRL IgM ELISA was set to optimally distinguish between dengue virus and nonflavivirus infections but was too low to optimally distinguish between dengue virus and JE virus infections. Indeed, there was little difference between the detection levels for dengue virus and JE virus infections in the MRL ELISA. The cutoff value of the PanBio IgM ELISA was set slightly above the optimal level indicated by TC-ROC analysis, but this setting is allowable, since the PanBio ELISA uses IgG to improve sensitivity for secondary dengue (i.e., the PanBio ELISA does not use only IgM).

These studies highlight the importance of selecting appropriate serum panels for the evaluation of dengue diagnostic assays. Of particular importance are other flavivirus infections (e.g., JE and yellow fever) and nonflavivirus infections with similar clinical presentations (e.g., malaria, typhoid, and leptospirosis). Sensitivity can be maximized by simply reducing the cutoff value used in the test, although doing so will be at the expense of specificity. It is interesting to note that, like the MRL ELISA, other commercially available IgM capture ELISAs that have been reported show high cross-reactivity for other flavivirus (yellow fever) and malaria infections (19, 21, 35). Due to the cross-reactivity among antibodies produced in JE, dengue, and yellow fever (23), one would expect similar results in other regions where different flaviviruses cocirculate (e.g., dengue and yellow fever in South America), although this idea needs to be confirmed by the appropriate trials. The endemic nature of these diseases in some regions and their asymptomatic presentation in most cases also complicate diagnosis further, as coinfection can occur.

The combined use of IgG and IgM is an alternate strategy for the diagnosis of dengue virus infection, since sensitivity for secondary dengue is improved and specificity for other infections is also improved. Furthermore, the pattern of IgM and IgG reactivity in the PanBio ELISA could be used to distinguish between dengue and other infections, since 58 of 80 dengue patients (73%) showed an elevation of IgM with or without IgG, while patients with non-dengue virus infections (including JE) did not show an elevation of IgM. Consequently, a positive IgM test in the PanBio ELISA had a positive predictive value of 100% for dengue virus infection, and cross-reactivity was of concern only for the minority of patients with dengue virus infection who were IgG positive and IgM negative in the PanBio ELISA. The additional use of IgG also allows the distinction between primary and secondary dengue. In this study, only 4 of 40 primary infections (10%) and 35 of 40 secondary infections (88%) showed an elevation of IgG in the PanBio ELISA.

The MRL and PanBio ELISAs used in this study should prove useful in the diagnostic laboratory. The choice of test will depend on a number of factors, such as the clinical setting, local conditions, and user preference.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and PanBio Pty Ltd. (Brisbane, Australia) through a cooperative research and development agreement. The PanBio Dengue Duo ELISA was developed through an Australian Government-sponsored Cooperative Research Center for Diagnostic Technologies.

We thank Panor Srisongkram for performing the AFRIMS reference ELISA; Ming Choohong for performing the hemagglutination inhibition assay; Rachel Kneen for specimen and data management; Tipawan Kungvanrattana for data entry; and the directors and staff of the Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health and the Centre for Tropical Diseases as well as Nicholas White for their support. We also thank George Watt, Department of Medicine, AFRIMS, Bangkok, Thailand, for providing sera and indirect immunoperoxidase data from patients with scrub typhus; William Winslow, Institute for Medical and Veterinary Science, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, for providing sera and microscopic agglutination test results from patients with leptospirosis; Rodney Jones, Gribbles Pathology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for providing Widal Felix test-positive sera from patients with typhoid; and Peter Nasveld, Australian Army Malaria Institute, Enogera, Queensland, Australia, for providing blood smear-positive sera from patients with malaria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bundo K, Igarashi A. Antibody capture ELISA for detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies in sera from Japanese encephalitis and dengue haemorrhagic fever patients. J Virol Methods. 1985;11:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(85)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardosa M J, Tio P H, Nimmannitya S, Nisalak A, Innis B. IgM capture ELISA for detection of IgM antibodies to dengue virus: comparison of 2 formats using hemagglutins and cell culture derived antigens. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:726–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardosa M J, Baharudin F, Hamid S, Hooi T P, Nimmannitya S. A nitrocellulose membrane based IgM capture enzyme immunoassay for etiological diagnosis of dengue virus infections. Clin Diagn Virol. 1995;3:343–350. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(94)00049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong C F, Ngoh B L, Tan H C, Yap E H, Singh M, Chan L, Chan Y C. A shortened dengue IgM capture ELISA using simultaneous incubation of antigen and peroxidase-labeled monoclonal antibody. Clin Diagn Virol. 1994;1:335–341. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chungue E, Boutin J P, Roux J. Significance of IgM titration by an immunoenzyme technique for the serodiagnosis and epidemiological surveillance of dengue in French Polynesia. Res Virol. 1989;140:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(89)80100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devine P, Cuzzubbo A, Marlborough D. Dengue fever testing. Today’s Life Sci. 1997;9:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadkari M K, Henchal E A, McCown J M, Brandt W E, Dalrymple J M. IgM antibody capture ELISA in the diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue virus infections. Indian J Med Res. 1982;80:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner M, Sohr D, Gobel P. A modified ROC analysis for the selection of cut-off values and the definition of intermediate results of serodiagnostic tests. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00121-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gubler D J, Clark G G. Dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever: the emergence of a global health problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:55–57. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.952004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gubler D J. Serological diagnosis of dengue haemorrhagic fever. Dengue Bull. 1996;20:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halstead S B, O’Rourke E J. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J Exp Med. 1977;146:201–217. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halstead S B. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science. 1988;239:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoke C H, Vaughn D W, Johnson R T, Nisalak A, Intralawan P, Poolsuppasit S, Jongsawas V, Titsyakorn U. Effect of high-dose dexamethasone on the outcome of acute encephalitis due to Japanese encephalitis virus. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:631–637. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Innis B. Antibody responses to dengue virus infection. In: Gubler D J, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. New York, N.Y: CAB International; 1997. pp. 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Innis, B. Personal communication.

- 16.Innis B L. Japanese encephalitis. In: Porterfield J S, editor. Exotic viral infections. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.; 1995. pp. 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Innis B L, Nisalak A, Nammannitya S, Kusalerdchariya S, Chongswasdi V, Suntayakorn S, Puttisri P, Hoke C H. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to characterise dengue infections where dengue and Japanese encephalitis co-circulate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:418–427. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuno G, Gomez I, Gubler D J. An ELISA procedure for the diagnosis of dengue infections. J Virol Methods. 1991;33:101–113. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(91)90011-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuno G, Cropp C B, Wong-Lee J, Gubler D J. Evaluation of an IgM immunoblot kit for dengue diagnosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:757–762. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam S K. Rapid dengue diagnosis and interpretation. Malay J Pathol. 1993;15:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam S K, Fong M Y, Chungue E, Doraisingham S, Igarashi A, Khin M A, Kyaw Z T, Nisalak A, Roche C, Vaughn D W, Vorndam V. Multicentre evaluation of dengue IgM dot immunoassay. Clin Diagn Virol. 1996;7:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0197(96)00257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam S K, Devine P L. Evaluation of capture ELISA and rapid immunochromatographic test for the determination of IgM and IgG antibodies produced during dengue infection. Clin Diagn Virol. 1998;10:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0197(98)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makino Y, Tadano M, Saito M, Maneekarn N, Sittisombut N, Sirisanthana V, Poneprasert B, Fukunaga T. Studies on serological cross-reaction in sequential flavivirus infections. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:951–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metz C E. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monath T P. Dengue: the risk to developed and developing countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2395–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer C J, King S D, Caudrado R R, Perez E, Baum M, Ager A L. Evaluation of the MRL Diagnostics dengue fever virus IgM capture ELISA and the PanBio rapid immunochromatographic test for diagnosis of dengue fever in Jamaica. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1600–1601. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1600-1601.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruechusatawat K, Morita K, Tanaka M, Vongcheree S, Rojanasuphot S, Warachit P, Kanai K, Thongtradol P, Nimnakorn P, Kanungkid S, Igarashi A. Daily observation of antibody levels among dengue patients detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Jpn J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;22:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sang C T, Lim S H, Cuzzubbo A, Devine P L. Clinical evaluation of rapid immunochromatographic test for the diagnosis of dengue infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:407–409. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.3.407-409.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sang C T, Cuzzubbo A, Devine P L. Evaluation of commercial capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies produced during dengue infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:7–10. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.1.7-10.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaughn D W, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, Innis B L, Nimmannitya S, Suntayakorn S, Rothman A L, Ennis F A, Nisalak A. Dengue in early febrile phase: viremia and antibody responses. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:322–330. doi: 10.1086/514048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughn D W, Nisalak A, Kalayanarooj S, Solomon T, Dung N M, Cuzzubbo A, Devine P L. Evaluation of rapid immunochromatographic test for diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:234–238. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.234-238.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaughn D W, Nisalak A, Solomon T, Kalayanarooj S, Dung N M, Kneen R, Cuzzubbo A, Devine P L. Rapid serological diagnosis of dengue virus infection using a commercial capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that distinguishes primary and secondary infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:693–698. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vorndam V, Kuno G. Laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infections. In: Gubler D J, Kuno G, editors. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. New York, N.Y: CAB International; 1997. pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Dengue haemorrhagic fever diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu S J L, Banson B, Paxton H, Nisalak A, Vaughn D W, Rossi C, Henchal E A, Porter K R, Watts D M, Hayes C G. Evaluation of dipstick enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies to dengue virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:452–457. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.452-457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H, Lohr J, Greiner M. The selection of ELISA cut-off points for testing antibody to Newcastle disease by two-graph receiver-operating characteristic (TG-ROC) analysis. J Immunol Methods. 1997;13:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]