Abstract

Introduction

Tobacco couponing continues to be part of contemporary tobacco marketing in the United States. We performed a systematic review of the evidence of tobacco product coupon receipt and redemption to inform regulation.

Aims and Methods

We searched EMBASE OVID and Medline databases for observational (cross-sectional and longitudinal) studies that examined the prevalence of tobacco coupon receipt and coupon redemption across different subpopulations, as well as studies of the association between coupon receipt and redemption with tobacco initiation and cessation at follow-up. We extracted unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the associations between coupon exposure (receipt, redemption) and tobacco use outcomes (initiation, cessation) and assessed each studies’ potential risk of bias.

Results

Twenty-seven studies met the criteria for inclusion. Of 60 observations extracted, 37 measured coupon receipt, nine measured coupon redemption, eight assessed tobacco use initiation, and six assessed cessation. Tobacco product coupon receipt and redemption tended to be more prevalent among younger adults, women, lower education individuals, members of sexual and gender minorities, and more frequent tobacco users. Coupon receipt at baseline was associated with greater initiation. Coupon receipt and redemption at baseline were associated with lower cessation at follow-up among tobacco users. Results in high-quality studies did not generally differ from all studies.

Conclusions

Tobacco product coupon receipt and redemption are often more prevalent among price-sensitive subpopulations. Most concerning, our results suggest coupon receipt may be associated with higher tobacco initiation and lower tobacco cessation. Couponing thereby increases the toll of tobacco use and could prove to be a viable public health policy intervention point.

Implications

A systematic review was conducted of the scientific literature about the receipt, redemption, and effects on tobacco initiation and cessation of tobacco product couponing. This review found that tobacco coupons are more often received by price-sensitive persons and these coupons serve to increase tobacco initiation and decrease tobacco cessation. Policy efforts to address these consequences may help curb tobacco’s harms and address health inequities.

Introduction

The marketing of tobacco products under contemporary US regulatory policy is led not by billboard imagery or even social media hashtags, but by distributing monies that make tobacco products cheaper to purchase.1 These monies represent the vast majority of the contemporary tobacco industry’s marketing efforts in the United States.2–5 The strategy takes on added importance since tobacco taxes are often considered the most effective tobacco control strategy in reducing cigarette use6 and their impact on smoking occurs through increased prices.7–9

Tobacco companies directly reduce the prices faced by consumers through various strategies (eg, quantity discounts, geographic price variations), but here we focus on the use of coupons. Coupons provide consumers a voucher via direct mail, magazines, e-mail, internet, or smartphone app that can be used to reduce the cost of a tobacco product from a retailer.10–12 Tobacco manufacturers build customer databases to, among other things, ensure that the distribution of these coupons maximizes sales to current and potential customers.5,13 Coupons represent a key point of contact between modern tobacco marketing and the consumer and are a useful proxy for the reach and effects of tobacco marketing.

Companies raise prices and then price discriminate to avoid losing the most price-sensitive smokers.14,15 Specifically, manufacturers may employ price discrimination, whereby they reduce prices to those consumers who are most price-sensitive (such as youth and low-income individuals) while selling products at a higher price to less price-sensitive consumers.16–18 This practice is not only profitable but also helps tobacco companies to maintain their customer base in the face of increasing prices and taxes.19

Tobacco coupons have been the subject of many scientific studies, but a systematic review of their (1) receipt, (2) redemption, and (3) associations with tobacco initiation and cessation is lacking. We address this research gap and provide an overview of the consistency of the distributional and behavioral impact of this mainstay of tobacco marketing, from which we can begin to understand the effects of price discount regulation. In this paper, we review the evidence of exposure to and the effects of couponing on smoking initiation and cessation, broken down by product category and sociodemographic subpopulation groups.

Methods

Study Protocol

This systematic review focused on peer-reviewed studies examining tobacco coupons. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.20 The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42021244653). No amendments to the original protocol were filed with PROSPERO.

Search Strategy and Search Terms

We searched EMBASE OVID and Medline databases on January 5 and September 20, 2021, to identify articles published from January 2002 to December 2020 reporting on tobacco products and exposure to price-reducing marketing tactics. Search terms were developed with the aid of a scientific librarian and are listed in Appendix I. We then also screened the cited references in all relevant identified articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included observational studies that examined differences in tobacco coupon receipt or redemption across subpopulation groups (sex, age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, tobacco use intensity, and sexual minority). Studies were also included and used to examine tobacco use behavioral outcomes if they used longitudinal data to examine the association between baseline exposure to couponing (receipt or redemption) and tobacco initiation at follow-up among baseline nonusers or tobacco cessation among baseline tobacco users. The exclusion criteria of this systematic review were animal studies, clinical studies, modeling studies, policy pieces, reviews, qualitative studies, focus group studies, and a lack of data on the three outcomes of interest: (1) receiving coupons, (2) redeeming coupons, and (3) the association between coupon receipt or redemption and tobacco product initiation (never users starting tobacco use) or cessation (tobacco users attempting to quit or succeeding at quitting tobacco use).

Study Selection

One author (ACL) conducted the primary literature search. Using the systematic reviewing software, Rayyan, duplicates were deleted and two authors (ACL and LMS-R) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility before completing the full-text review.21 In instances of disagreement between the authors, a consensus was reached through discussion.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We developed a data abstraction template in Google Sheets. Data extracted included: the location of the study, years of data collection, sampling strategy, sample size, data collection method, sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco products covered, statistical approach, outcomes, and results. Results in the form of unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and confidence intervals for each subgroup and price-reducing marketing tactic (coupon receipt or redemption) and tobacco product type were extracted. When results were presented in the original articles that used different referent and comparison groups than the systematic review, we performed appropriate statistical transformations to extract comparable results to other studies. We did not combine results across stratified populations (as chosen by the original study authors) and authors occasionally reported single findings (observations) for multiple outcomes of interest. This led to the extraction of a varying number of observations from each study.

Studies were categorized by the three main outcomes (listed above). Studies of the receipt or redemption of coupons, either cross-sectional or longitudinal, examined the percent of the population receiving or using coupons, and the sociodemographic characteristics of the population. The studies that examined initiation or cessation of tobacco use were longitudinal and considered behaviors at follow-up after exposure to couponing (receipt or redemption) at baseline.

The collected odds ratios examined differences in the three outcomes across the following subpopulations: (1) Sex, male (referent) or female, (2) Age, young or old (referent), (3) Race/Ethnicity, Black, Indigenous or Person of Color [BIPOC] (referent) or non-BIPOC, (4) Educational Attainment, high (referent) or low, (5) Intensity of Tobacco Use, high or low (referent) (variously measured), and (6) Sexual and Gender Minority, LGBTQ+ (referent) or non-LGBTQ+. Details about the categories used for each study are described in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 in Appendix III.

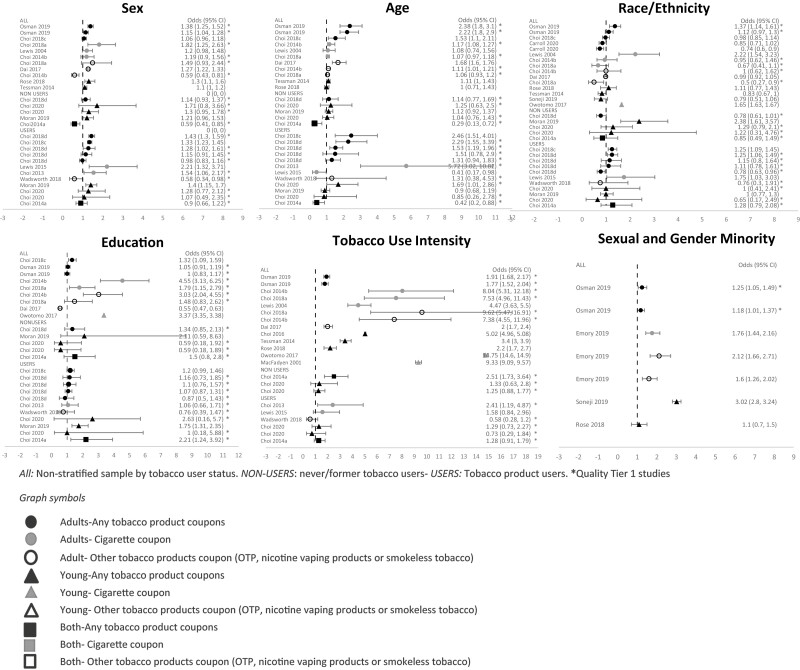

We summarized the results and extracted patterns of statistical associations from the identified studies, and designated those findings with odds ratios whose 95% confidence intervals do not overlap 1 were significant.22 We decided against performing a meta-analysis because the studies were too heterogeneous (using different definitions of tobacco couponing, classification variables, and drawing from different samples) and had overlapping samples. We reported patterns of consistency across outcome and subpopulation, distinguished by the type of population (adults [18+ years], youth [18 years or less], or both [12+ years]), the type of tobacco product coupon (any product [including an unspecified type], cigarettes, or other tobacco products [including cigars, smokeless tobacco, snus, and nicotine vaping products (NVPs)]), and the type of tobacco users (tobacco users, nonusers, or both) in any given sample. We also analyzed patterns among only the highest quality studies to test the sensitivity of the results to study quality (detailed below). When we do not report results across a particular subpopulation or observation type, those findings are included in Appendix IV. Forest plots summarizing the magnitude of the association (Figures 2–7) for receipt studies were created.23 All analyses were performed using Stata/MP 16.1.24

Quality Assessment

Two researchers (ACL and LMS-R) independently assessed the studies’ potential risk of bias by using the National Toxicology Program Office for Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating.25 The results of the bias assessment comprised seven domains regarding selection, confounding, attrition/exclusion, confidence in exposure and outcome, and internal validity threats. Each domain was rated as definitely low risk, probably low risk, probably high risk, or definitely high risk. Studies that were rated as being definitely or probably low risk of bias across all domains were classified as top quality (Tier 1). Studies that had one or two domains at probably high or definitely high risk of bias were classified as the middle tier in quality (Tier 2), while studies with three or more such domains at probably or definitely high risk of bias were classified as the bottom tier in quality (Tier 3). Discrepancies were resolved by a consensus among the researchers (ACL and LMS-R) (Supplementary Table 2 in Appendix II).

Results

Study Characteristics

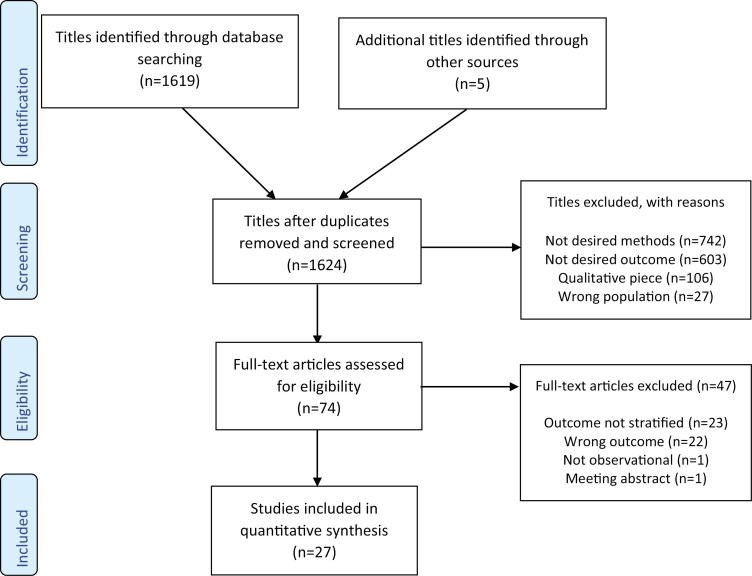

As shown in Figure 1, our initial search identified 1624 studies, and a total of 27 studies were selected for inclusion in the synthesis. From those 27 studies, we extracted 60 observations, of which 37 measured coupon receipt (21 studies) and nine measured coupon redemption (nine studies). In addition, initiation among nonusers and cessation among tobacco users following coupon exposure at baseline were evaluated in eight and six observations, respectively, from four studies each.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection. To see the reason that full-text articles were excluded from the study, please see Supplementary Table 6 in Appendix V.

Regarding country of origin, 25 studies (representing 58 observations) were conducted using data drawn exclusively from the United States. One study26 drew data from four countries (United States, England, Canada, and Australia), while another study27 focused on Northeast England. Appendix II details information of the included studies, including the results of the quality assessment. Of the 27 studies, 11 were rated highest quality (Tier 1), 14 were rated middle quality (Tier 2), and two were rated low quality (Tier 3).

Receipt of Coupons

The findings from the 21 studies that produced 37 observations are listed in Supplementary Table 5 in Appendix IV. Broadly, coupon receipt was found to be higher among individuals who are high-intensity tobacco users or sexual and gender minorities relative to their counterparts. The median prevalence of coupon receipt in the samples from 16 studies where it was reported was 10.6% (min 5.4%, max 49.4%), but when restricted to samples of tobacco users the mean prevalence of coupon receipt was 23.3%. Below we report the top-level findings in each subpopulation, additional details examining the heterogeneity of outcomes for coupon receipt within each subpopulation are included in Appendix IV.

Sex

Of the 28 observations that examined coupon receipt by sex (Figure 2, Panel A), half found a gender effect and half did not: 11 found that females had significantly higher odds of coupon receipt than males (AORs from 1.15 to 2.21), while three found that females had significantly lower odds of coupon receipt (AORs from 0.58 to 0.59). The remaining 14 found no statistically significant association. When restricted to the 19 observations from the highest quality studies (Tier 1), six observations found that females had significantly higher odds of coupon receipt than males (AORs from 1.15 to 1.82), three found that females had lower odds (AORs from 0.58 to 0.59), and five found no association. Females generally received more tobacco product coupons than males in the majority of cases, although the association was nonsignificant in some cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association of the receipt of tobacco product coupons by tobacco product use status across Sex, Age, Race/Ethnicity, Education, Tobacco Use Intensity, and Sexual and Gender Minority Status. All: nonstratified sample by tobacco user status. NON-USERS: never/former tobacco user. USERS: tobacco product users. *Quality Tier 1 studies.

Observations from adult-only samples found an association between being female and significantly higher odds of coupon receipt more often (nine of 18, AORs from 1.15 to 2.21) than in youth-only samples (two of eight, AORs from 1.30 to 1.40). No clear differences in patterns of coupon receipt by sex appeared when compared across the type of tobacco product coupon and by tobacco use status.

Age

Among the 28 observations that examined coupon receipt by age, 11 found that younger (primarily adult) respondents had significantly higher odds of coupon receipt than older respondents (AORs from 1.11 to 5.72), while three found an inverse association (AORs from 0.29 to 0.42) and 14 observations found no significant association. When findings were restricted to the 19 observations from the highest quality studies (Tier 1), eight found younger (vs. older) respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt (AORs from 1.11 to 5.72) while two observations from a single study28 found an inverse association (AORs from 0.29 to 0.42). Of note, four of the observations from two studies29,30 coded age as a continuous variable, rather than a categorical variable as used in the other 24 observations. Overall, younger respondents received more coupons than older respondents more often than the inverse, but the association is not significant across some studies. However, the association between age and coupon receipt was more consistent among higher-quality studies (Figure 2, Panel B).

The age gradient observed in coupon receipt was concentrated among adults. For the 18 adult-only observations, 10 found that younger respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt than older respondents (AORs from 1.11 to 5.72), compared with just one31 which found an inverse association (AOR = 0.41), with seven finding no statistically significant association. By contrast, only one observation30 (AOR = 1.69) of the eight observations from youth-only samples found a positive association, compared with seven that found no statistically significant association. Overall, no major differences between age gradients were observed across the type of tobacco product coupon received or by tobacco use status.

Race/Ethnicity

Race/ethnicity was reported as a comparison between Black, Indigenous, and People Of Color (BIPOC) as the reference group and non-BIPOC. Of the 31 observations (Figure 2, Panel C), 21 found no association, seven found that non-BIPOC had higher odds of coupon receipt than BIPOC (AORs from 1.25 to 2.38) while three found non-BIPOC had lower odds of coupon receipt than BIPOC (AORs from 0.50 to 0.78). When limiting to the 18 observations from highest quality studies, two found higher32,33 (AORs from 1.25 to 1.37) and two found lower32,34 (AORs from 0.50 to 0.78) odds of coupon receipt for non-BIPOC. The association between race/ethnicity and coupon receipt was predominantly nonsignificant and different among higher-quality studies. In addition, no clear association was found between race/ethnicity to coupon receipt across age-and-sample makeup, by tobacco use, or the type of tobacco product coupon.

Educational Attainment

Our review resulted in 12 studies that produced 25 observations evaluating the association between coupon receipt and educational attainment (Figure 2, Panel E). Across 16 observations that assessed adult-only samples, this was consistently coded as the respondents’ level of education. For the nine observations of youth, the level of a parent’s education served as a proxy. Of the total 25 observations, seven found that low educational attainment respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt than high education respondents (AORs from 1.32 to 4.55), compared with only one,35 focusing on coupons for nicotine vaping products, that reported lower odds of coupon receipt among those of low education (AOR = 0.55), while 17 found no association. When restricted to the 19 observations from the highest quality studies (Tier 1), four found low education respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt (AORs from 1.79 to 4.55) while the remaining 15 showed no significant association.

The results for education were not systematically related to whether the sample surveyed youth or adults. When considering the type of tobacco product coupon, three of four studies that focused on cigarette users found that low education had significantly higher exposure to coupon receipt than high education (AORs from 1.79 to 4.55), one study35 found a negative association with low education for NVPs, while 14 of 17 observations for any tobacco coupon found null results. Nonusers did not show significant results.

Tobacco Use Intensity

The measure of tobacco use intensity varied across the studies and sometimes differed within studies, including living with tobacco users, daily versus nondaily use, and the number of cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days. We defined the reference category for our analysis as the group of lowest intensity (see Supplementary Table 3 in Appendix III). Fifteen of the 22 observations found high-intensity respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt than low-intensity respondents (AORs from 1.77 to 14.75), while seven observations found no difference in the odds of coupon receipt by intensity (Figure 2, Panel E). When limited to the 14 observations from high-quality studies, eight observations found the high-intensity group had higher odds of coupon receipt while six found no significant association. This indicates that tobacco use intensity is on average positively associated with coupon receipt.

All 13 observations that did not stratify by tobacco use status found that high-intensity respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt than low-intensity respondents (AORs from 1.77 to 14.75). No significant association was seen among observations stratified by tobacco use status. The results for tobacco use intensity were also not sensitive to age or type of tobacco product coupon.

Sexual and Gender Minority

Among the seven observations that considered sexual and gender minorities, all five observations from adult-only and one from youth-only samples found sexual and gender minority respondents had higher odds of coupon receipt than non-LGBTQ+ respondents (AORs from 1.18 to 3.02). Just one study33 was considered high quality, which also found that LGBTQ+ respondents had higher exposure to receipt of coupons (AOR = 1.21) (Figure 2, Panel F). However, no clear association between LGBTQ+ versus non-LGBTQ+ individuals and coupon receipt across age, tobacco user type, and tobacco product coupon was observed.

Redemption of Coupons

The odds ratios of the nine studies included for coupon redemption are listed in Table 1 (comparator groups listed in Supplementary Table 4 in Appendix III). Each study of coupon redemption reported the overall prevalence of coupon redemption in their samples. On average 26.7% (min = 15.0%, max = 50.0%) of the samples reported redeeming coupons. Only one study36 examined non-cigarette coupon redemption and found that 15% of NVP users (n = 282) reported redeeming coupons for NVPs.

Table 1.

Tobacco Product Coupon Redemption Across Subpopulations

| Study name | Location | Period | Sample method | Size/strata | % Using coupons | AOR sex | AOR age | AOR race | AOR SES | AOR intensity | AOR sexual minority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redemption of cigarette coupons | |||||||||||

| Choi 201237 | Minnesota, United States | 2009 | Telephone longitudinal | 18+ smokers (n = 718) | 48.5% | 1.32 [0.95–1.85] |

8.33 [4.35–100.0] |

2.38 [1.41–4.00] |

1.25 [0.59–2.62] |

2.23 [1.48–3.38] |

|

| Choi 201838 | Minnesota, United States | 2010–2014 | Telephone longitudinal | 18+ smokers (n = 2177) | 50.0% | 1.30 [0.93–1.82] |

5.23 [2.45–11.19] |

1.92 [1.18–3.13] |

1.18 [0.59–2.34] |

1.24 [0.64–2.40] |

|

| Lewis 200439 | New Jersey, United States | 2002 | Telephone cross-sectional | 18+ smokers and recent quitters (n = 1401) | 21.1% | 1.83 [1.32–2.54] |

0.60 [0.32–1.09] |

2.27 [1.23–4.17] |

1.80 [0.89–3.46] |

||

| Jane Lewis 201531 | Nationwide, United States | 2011 | Telephone cross-sectional | 18–34 smokers (n = 699) | 24.2% | 1.87 [1.08–3.24] |

0.93 [0.28–3.03] |

2.08 [1.15–3.85] |

2.97 [1.41–6.24] |

||

| Osman 201933 | Nationwide, United States | 2013–2014 | PATH cross-sectional | 18+ all (n = 10 994) | 22.0% | 1.23 [1.09–1.40] |

2.94 [2.10–4.00] |

1.45 [1.20–1.72] |

1.23 [1.06–1.43] |

2.01 [1.79–2.26] |

1.18 [1.01–1.39] |

| Xu 201340 | Nationwide, United States | 2009–2010 | NATS cross-sectional | 18+ smokers (n = 14 891) | 19.8% | 3.19 [3.00–3.38] |

|||||

| Xu 201441 | Nationwide, United States | 2009–2010 | NATS cross-sectional | 18+ smokers (n = 16 542) | 19.6% | 1.14 [1.06–1.23] |

4.19 [4.05–4.34] |

1.33 [1.22–1.43] |

1.53 [1.42–1.65] |

1.07 [0.96–1.19] |

|

| Xu 201642 | Nationwide, United States | 2009–2010 | NATS cross-sectional | 18+ smokers (n = 15 536) | 19.6% | 1.20 [1.00–1.40] |

2.00 [1.43–3.33] |

1.43 [1.11–2.00] |

1.43 [1.00–2.00] |

1.10 [0.90–1.50] |

|

| Redemption of nicotine vaping product coupons | |||||||||||

| Ali 201836 | Nationwide, United States | 2015–2016 | Internet cross-sectional | 18+ NVP users (n = 282) | 15.0% | 0.76 [0.37–1.58] |

1.19 [0.57–2.50] |

0.69 [0.30–1.56] |

1.04 [0.48–2.23] |

2.57 [1.18–5.56] |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; NATS = National Adult Tobacco Survey; PATH = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health. Reference categories for each subgroup: (1) Sex, male (ref) or female, (2) Age, old (ref) or young, (3) Race/Ethnicity, Black, Indigenous or Person of Color [BIPOC] (ref) or non-BIPOC, (4) Educational Attainment, high (ref) or low, (5) Intensity of Tobacco Use, high or low (ref) (variously measured), and (6) Sexual Minority, LGBTQ+(ref) or non-LGBTQ.

Sex differences in the redemption of coupons were assessed in eight observations. Four reported that females had significantly higher odds of using coupons than males (AORs from 1.14 to 1.87), while the other four found no statistically significant association. When restricted to the three highest quality studies, two33,42 found that females had higher odds of coupon redemption than males (AORs from 1.20 to 1.23), and the third found no association.

Age differences in the redemption of coupons were assessed in eight observations. Five found that younger respondents had significantly higher odds of coupon redemption than older respondents (AORs from 2.00 to 8.33), and three found no association. When restricted to the three observations from highest quality studies, all found that younger respondents were significantly more likely to have redeemed coupons than older respondents (AORs from 2.00 to 8.33).

Race/ethnicity differences in the redemption of coupons were assessed in eight observations. Seven found that non-BIPOC respondents had higher odds of coupon redemption than BIPOC respondents (AORs from 1.33 to 2.38), while one36 found no association. When restricted to the three observations from the highest quality studies, all found non-BIPOC were significantly more likely to redeem coupons than BIPOC (AORs from 1.43 to 2.38).

Educational attainment or parental education differences in the redemption of coupons were assessed in six observations. Three found that lower education respondents had significantly higher odds of coupon redemption than higher education respondents (AORs from 1.23 to 1.53), while the remainder had a positive, but nonsignificant association for lower education. When restricted to the three observations from the highest quality studies, two33,42 found a significant association between coupon redemption and higher educational attainment (AORs from 1.23 to 1.43), and one found no association.

Tobacco use intensity differences in the redemption of coupons were assessed in nine observations. Five observations reported that high-intensity respondents had higher odds of coupon redemption than low-intensity respondents (AORs from 2.01 to 3.19). When restricted to the three high-quality studies, two33,37 reported a significant association between tobacco use intensity and coupon redemption (AORs from 2.01 and 2.23).

Just one (high quality) study considered coupon redemption by sexual and gender minority status,33 finding that LGBTQ+ respondents had a higher rate of cigarette coupon redemption than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts (AOR = 1.18).

Impact on Tobacco Initiation and Smoking Cessation

Table 2 shows the result of longitudinal studies that assessed the association between coupon receipt or redemption at baseline and tobacco (mostly cigarette smoking) initiation and cessation at follow-up. Initiation was generally defined as past 30-day tobacco use at follow-up after never using tobacco at baseline, while cessation was generally defined as no tobacco use in the past 30 days at follow-up after using tobacco at baseline, but studies collected did deviate from these definitions, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies of the Effects of Price-Reducing Marketing Exposure at Baseline on Tobacco Cessation or Initiation at Follow-up

| Study name | Location | Period | Sample method | Size/strata | Baseline exposure | Follow-up outcome | AOR effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on cessation | |||||||

| Any tobacco product | |||||||

| Choi 201843 | Nationwide, United States | 2013–2015 | PATH longitudinal | 18+ current smokers (n = 9282) | Receipt | Not smoking in past 6 months | 0.71 [0.58−0.88] |

| Cigarettes | |||||||

| Choi 201237 | Minnesota, United States | 2009 | Telephone longitudinal | 18+ smokers (n = 718) | Redemption | Not smoking in past 30 days | 1.10 [0.64−1.89] |

| Choi 20134 | Minnesota, United States | 2007–2009 | MATS longitudinal | 20+ current or former smokers (n = 352) | Receipt not redemption | Not smoking in past 30 days | 2.90 [1.20−7.03] |

| 20+ current or former smokers (n = 529) | Redemption | Not smoking in past 30 days | 0.16 [0.06−0.60] | ||||

| Choi 201429 | Midwest, United States | 2010–2012 | Telephone longitudinal | 20–28 users (n = 284) | Receipt | Cessation attempt in past 12 months | 0.53 [0.32−0.89] |

| 20–28 users (n = 109) | Receipt | Not smoking in past 30 days | 0.51 [0.26−0.99] | ||||

| Effect on initiation | |||||||

| Any tobacco product | |||||||

| Choi 201843 | Nationwide, United States | 2013–2015 | PATH longitudinal | 18+ never smokers (n = 5775) | Receipt | Ever smoking | 2.28 [1.36−3.83] |

| Rose 201844 | Nationwide, United States | 2013–2015 | PATH longitudinal | 12–17 never users (n = 8251) | Receipt | Ever smoking | 1.40 [1.10−1.90] |

| Choi 202030 | Nationwide, United States | 2013–2015 | PATH longitudinal | 12–18 nonusers (n = 8993) | Receipt | Past 30-day cigarette use | 2.24 [0.96−5.25] |

| Past 30-day NVP use | 1.05 [0.27−4.04] | ||||||

| Past 30-day cigar use | 4.55 [1.54−13.46] | ||||||

| Past 30-day smokeless use | 7.63 [1.22−47.64] | ||||||

| Past 30-day hookah use | 6.27 [2.63−14.93] | ||||||

| Cigarettes | |||||||

| Choi 201429 | Midwest, United States | 2010–2012 | Telephone longitudinal | 20–28 nonusers (n = 99) | Receipt | 100+ lifetime cigs and past 30-day use | 2.29 [1.11−4.75] |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; MATS = Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey; PATH = Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health.

Overall, coupon receipt among nonusers at baseline was associated with tobacco use initiation at follow-up in all four studies and five of eight observations. A Minnesota study28 found that nonuser young adults receiving direct mail promotions at baseline had higher odds of becoming smokers at follow-up (AOR = 2.29). A similar association was observed in an adult sample (AOR = 2.28).32 Similar findings were observed nationally for youth using the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study (PATH),30,44 which found that never users who received coupons had higher odds of reporting past 30-day tobacco use across a variety of products at follow-up (AORs from 1.05 to 7.63). One of these PATH studies30 with five observations did not find a significant association between coupon receipt and either cigarette or NVP use at follow-up while finding significant results for cigar, smokeless tobacco, and hookah use. No study was found during the systematic review that examined coupon redemption and initiation.

Six observations from four studies examined the associations between coupon receipt or redemption on cessation. Four studies assessed coupon receipt while two studies assessed the association of coupon redemption in relation to cessation. A Minnesota Adolescent Community Cohort study29 reported that young adult smokers receiving direct mail promotions had lower odds of reporting a quit attempt (AOR = 0.53) or successfully quitting (AOR = 0.51) compared with those who did not. Two studies using the same population survey (Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey Cohort Study) found contrasting results; one37 reported no association between any tobacco coupon redemption and cessation and the other4 reported that coupon redemptions were associated with lower odds of smoking in the past 30 days (AOR = 0.16). Overall, most studies reported that people who received or redeemed coupons at baseline had lower odds of cessation.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review focused on the receipt and redemption of tobacco coupons and the effects of those marketing activities on tobacco use. This systematic review found evidence that tobacco product coupons were received more often by persons of lower educational attainment, higher intensity tobacco users, and people who identify as sexual and gender minorities. The redemption of coupons, especially in conjunction with receipt, provides evidence of effectiveness in targeting particular customers. Like coupon receipt, the literature also reports greater coupon redemption by sexual and gender minorities, low educational attainment, and more frequent tobacco users, but also evidence of higher redemption among younger age groups, women, and non-BIPOC. The literature on the receipt and redemption of coupons provides evidence of the targeting of female, low socioeconomic status, and BIPOC customers by tobacco companies.2,45–48 Finally, our review found that coupon receipt or redemption is consistently associated with increased tobacco initiation among nonusers29,30,43,44 and reduced smoking cessation among current users.4,29,37,43

The results for both receipt and redemption of coupons are consistent with coupons as a tobacco industry strategy to price discriminate and that could reduce the impact of taxes.49 Young people and individuals of lower socioeconomic status are known to be most price-sensitive,7–9,50 so coupons could potentially encourage tobacco use initiation and discourage cessation. Studies also indicate that people who smoke at a higher intensity are more price-sensitive than people who smoke at a lower intensity,50,51 and thus, tobacco companies have more incentive to send coupons to these groups.

While our review provides an overview of the effects and exposures to tobacco product coupons, coupons made up only 3% for cigarettes and 7% for smokeless tobacco of total industry marketing expenditures in 2019.52 A recent systematic review53 of geographic variations in cigarette prices found consistent evidence that prices are lower in low socioeconomic status areas and areas with a higher proportion of young inhabitants, with suggestive evidence that menthol cigarettes are sold at lower prices in areas with higher concentrations of African Americans. Most of these discounts in prices likely occur through price promotions, the result of store specials and multipack discounts. These activities constitute the vast bulk of tobacco marketing expenditures and are less studied than couponing, likely due to difficulties in collecting the relevant data. However, due to the sheer scale of this form of price-reducing marketing and the documented effects of exposure to coupons, further research is warranted on its effects on tobacco use.

Our review indicates that couponing may target the most vulnerable groups, including those who are most price-sensitive (eg, low educational attainment and young adults), and could undermine the goals of tobacco taxation. This review was dominated by literature from the United States, and its policy implication flow most directly toward that country. At the subnational level in the United States, where preemption does not exist, further efforts at state and local levels to eliminate coupon redemption and evaluate compliance and impact are needed. At the federal level, the US Food and Drug Administration could eliminate coupon redemption at the point of sales via their authority to restrict the promotion of covered tobacco products under the Tobacco Control Act of 2009,54 just as states (eg, Massachusetts, New York) and localities have done.55 From the reviewed studies, only a few asked specific questions about the channel (mail, e-mail, or social media) by which the respondent received the coupons.33,35,39,56,57

Limitations

Our findings are subject to limitations. Almost all the studies applied data drawn exclusively from the United States, so it is unclear whether the results apply to other jurisdictions. Additionally, we excluded gray-literature articles from the scope of our search, potentially allowing us to miss some contributions to the couponing literature. Most of the effort in this area has been focused on determining patterns of receipt of coupons across population subgroups. While some of this work identifies subgroup differences in rates of coupon receipt, the literature limits us from determining if these associations are due to preexisting disparities in a variable like smoking status that is not distributed equally across educational attainment. The lack of results for coupon receipt for observations that stratified their samples by tobacco use status certainly speak to the possibility of a confounded common cause across two potential explanatory factors for elevated coupon receipt.

Further study should be directed at coupon redemption, as this was found to be associated with decreased tobacco cessation,4,29,37,43 especially among youth and for non-cigarette products. A notable omission from the systematic review were studies examining links between coupon receipt, coupon redemption, and prices paid,58 as prices paid ultimately influence demand for tobacco. Further consideration should be given to coupons for NVPs since recent literature indicates that firms have an incentive to reduce the price of the device and raise the price of liquids.59 In addition, nine studies out of 27 used the PATH survey. Other surveys with data on couponing exposure should be studied.

Most studies were cross-sectional, which raises the question of causality. Eight longitudinal studies were identified, which consider the impact on smoking behaviors. However, these studies may be subject to selection bias, eg, if tobacco companies target those individuals who are most likely to redeem coupons to reduce initiation or increase cessation or if those who redeem coupons are the individuals who are least likely to quit or most likely to initiate. Additionally, no study has yet examined cessation in excess of 1 year, suggesting the need for examining longer-term health-relevant follow-up work. More longitudinal and experimental analyses that control for these factors should be conducted to determine the directionality of these associations.

Finally, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis of our collected data, as the studies were too heterogeneous in composition and analytical strategy, and in multiple instances used overlapping samples. We advise readers to cautiously interpret our results, especially when sample characteristics determine whether such an association is observed, as is the case for education and tobacco use intensity. Further, the determination of what is considered “statistically significant” is fundamentally an arbitrary exercise and significance cutoffs should not be granted too much importance over assessing which trends are consistent and which are not. Despite these limitations, we believe that our synthesis without meta-analysis provides useful insights for tobacco control researchers without violating the assumptions that underpin a proper meta-analysis.

Conclusion

We find that receipt and redemption of tobacco product coupons were more prevalent in young adults, sexual and gender minority populations, people with lower educational attainment, or people with higher tobacco use intensity. Some evidence indicates that coupon redemption is associated with increased initiation of smoking among nonusers and decreased cessation among current users, but further study is needed. It appears that couponing is used to lower the price of tobacco in those who are most price-sensitive, thereby potentially undermining the impact of taxes on reducing tobacco use.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Jamie Tam, Cliff Douglas, Marie Knoll, and Nargiz Travis for their comments during the creation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Alex C Liber, Department of Oncology, Georgetown University-Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Luz María Sánchez-Romero, Department of Oncology, Georgetown University-Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Christopher J Cadham, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Zhe Yuan, Department of Oncology, Georgetown University-Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Yameng Li, Department of Oncology, Georgetown University-Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Hayoung Oh, Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Steven Cook, Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Kenneth E Warner, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Lisa Henriksen, Department of Oncology, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, USA.

Ritesh Mistry, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Rafael Meza, Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Nancy L Fleischer, Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

David T Levy, Department of Oncology, Georgetown University-Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through TCORS grant U54CA229974. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Authors’ Contribution

ACL and DTL conceived of the study. ACL and LMS-R screened and selected abstracts and full-text articles, extracted data, and performed the data analysis. ACL, LMS-R, and DTL wrote the initial manuscript draft. CJC, ZY, YL, HO, SC, KEW, LH, RM, and NLT aided the creation of the analytical strategy and edited the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Data extracted from studies and used for analysis, the data collection template, and the analytic code are available upon request from the authors.

References

- 1. Hiilamo H, Glantz S. FCTC followed by accelerated implementation of tobacco advertising bans. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):428–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 1):i62–i72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M. State variation in retail promotions and advertising for Marlboro cigarettes. Tob Control. 2001;10(4):337–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi K, Hennrikus DJ, Forster JL, Moilanen M. Receipt and redemption of cigarette coupons, perceptions of cigarette companies and smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis MJ, Ling PM. “Gone are the days of mass-media marketing plans and short term customer relationships”: tobacco industry direct mail and database marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2016;25(4):430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control. 2011;20(3):235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levy DT, Tam J, Kuo C, Fong GT, Chaloupka F. The impact of implementing tobacco control policies: the 2017 Tobacco Control Policy Scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(5):448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cancer Institute. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control (NCI Tobacco Control Monograph Series #21) [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2016. [accessed June 3, 2021]. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/m21_complete.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. National Cancer Institute. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2017. [accessed June 1, 2021]. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/monograph-22 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seidenberg AB, Jo CL. Cigarette couponing goes mobile. Tob Control. 2017;26(2):233–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navarro MA, O’Brien EK, Hoffman L. Cigarette and smokeless tobacco company smartphone applications. Tob Control. 2019;28(4):462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Brien EK, Navarro MA, Hoffman L. Mobile website characteristics of leading tobacco product brands: cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookah and cigars. Tob Control. 2019;28(5):532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sfekas A, Lillard DR. Do Firms Use Coupons and In-store Discounts to Strategically Market Experience Goods Over the Consumption Life-Cycle? The Case of Cigarettes [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. [accessed December 14, 2020]. https://www.nber.org/papers/w19310 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross H, Tesche J, Vellios N. Undermining government tax policies: common legal strategies employed by the tobacco industry in response to tobacco tax increases. Prev Med. 2017;105(Suppl):S19–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levy DT, Sánchez-Romero LM, Douglas CE, Sweanor DT. An analysis of the Altria-Juul Labs deal: antitrust and population health implications. J Competition Law Econ. 2021;17(2):458–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Varian HR. Chapter 10 Price discrimination [Internet]. In: Schmalensee R, Willig R (eds.), Handbook of Industrial Organization. Elsevier; 1989:597–654 [accessed January 4, 2021]. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1573448X89010137 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross H, Chaloupka FJ. The effect of cigarette prices on youth smoking. Health Econ. 2003;12(3):217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallet CA, List JA. Cigarette demand: a meta-analysis of elasticities. Health Econ. 2003;12(10):821–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orzechowski and Walker. The Tax Burden on Tobacco, 2019. Arlington, VA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4#article-info. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:16890. https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogilvie D, Fayter D, Petticrew M, et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. StataCorp. STATA. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT). Handbook for Conducting a Literature-Based Health Assessment Using OHAT Approach for Systematic Review and Evidence Integration [Internet]. Division of the National Toxicology Program National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; 2019. [accessed April 6, 2021]. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pubs/handbookmarch2019_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wadsworth E, McNeill A, Li L, et al. Reported exposure to E-cigarette advertising and promotion in different regulatory environments: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country (ITC-4C) Survey. Prev Med. 2018;112(July):130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacFadyen L, Hastings G, MacKintosh AM. Cross sectional study of young people’s awareness of and involvement with tobacco marketing. BMJ. 2001;322(7285):513–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Choi K, Forster J. Tobacco direct mail marketing and smoking behaviors in a cohort of adolescents and young adults from the U.S. upper Midwest: a prospective analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(6):886–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi K, Forster JL. Frequency and characteristics associated with exposure to tobacco direct mail marketing and its prospective effect on smoking behaviors among young adults from the US Midwest. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2179–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi K, Rose SW, Zhou Y, Rahman B, Hair E. Exposure to multimedia tobacco marketing and product use among youth: a longitudinal analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(6):1036–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jane Lewis M, Bover Manderski MT, Delnevo CD. Tobacco industry direct mail receipt and coupon use among young adult smokers. Prev Med. 2015;71(pm4, 0322116):37–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Choi K, Soneji S, Tan ASL. Receipt of tobacco direct mail coupons and changes in smoking status in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(9):1095–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Osman A, Queen T, Choi K, Goldstein AO. Receipt of direct tobacco mail/email coupons and coupon redemption: demographic and socioeconomic disparities among adult smokers in the United States. Prev Med. 2019;126(pm4, 0322116):105778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi K, Taylor N, Forster J. Sources and number of coupons for cigarettes and snus received by a cohort of young adults. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(1):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dai H, Hao J. Direct marketing promotion and electronic cigarette use among US adults, National Adult Tobacco Survey, 2013–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14(101205018):E84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ali FRM, Xu X, Tynan MA, King BA. Use of price promotions among U.S. adults who use electronic vapor products. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):240–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, St Claire AW. Use of price-minimizing strategies by smokers and their effects on subsequent smoking behaviors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(7):864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choi K, Boyle RG. Changes in cigarette expenditure minimising strategies before and after a cigarette tax increase. Tob Control. 2018;27(1):99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Slade J. Tobacco industry direct mail marketing and participation by New Jersey adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu X, Pesko MF, Tynan MA, et al. Cigarette price-minimization strategies by U.S. smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(5):472–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu X, Malarcher A, O’Halloran A, Kruger J. Does every US smoker bear the same cigarette tax? Addiction. 2014;109(10):1741–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu X, Wang X, Caraballo RS. Is every smoker interested in price promotions? An evaluation of price-related discounts by cigarette brands. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(1):20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi K, Chen JC, Tan ASL, Soneji S, Moran MB. Receipt of tobacco direct mail/email discount coupons and trajectories of cigarette smoking behaviours in a nationally representative longitudinal cohort of US adults. Tob Control. 2018;28(3):282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rose SW, Glasser AM, Zhou Y, et al. Adolescent tobacco coupon receipt, vulnerability characteristics and subsequent tobacco use: analysis of PATH Study, Waves 1 and 2. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e50–e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee JGL, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the USA. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e139–e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry promotional strategies targeting American Indians/Alaska Natives and exploiting Tribal sovereignty. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(7):940–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cruz TB, Wright LT, Crawford G. The menthol marketing mix: targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 2):S147–S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sheikh ZD, Branston JR, Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry pricing strategies in response to excise tax policies: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2021. [accessed August 12, 2021]. http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/08/01/tobaccocontrol-2021-056630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Differential effects of cigarette price changes on adult smoking behaviours. Tob Control. 2014;23(2):113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen C-M, Chang K-L, Lin L. Re-examining the price sensitivity of demand for cigarettes with quantile regression. Addict Behav. 2013;38(12):2801–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2019 and Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2019 [Internet]. Federal Trade Commission; 2021. [accessed June 18, 2021]. https://www.ftc.gov/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2019-smokeless-tobacco-report-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guindon GE, Fatima T, Abbat B, Bhons P, Garasia S. Area-level differences in the prices of tobacco and electronic nicotine delivery systems—a systematic review. Health Place. 2020;65(September):102395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Doogan NJ, Wewers ME, Berman M. The impact of a federal cigarette minimum pack price policy on cigarette use in the USA. Tob Control. 2018;27(2):203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tobacco Coupon Regulations and Sampling Restrictions [Internet]. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; 2011. [accessed June 21, 2021]. https://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-tobcouponregsandsampling-2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carroll DM, Soto C, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. Tobacco industry marketing exposure and commercial tobacco product use disparities among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(2):261–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Choi K. The associations between exposure to tobacco coupons and predictors of smoking behaviours among US youth. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pesko MF, Xu X, Tynan MA, et al. Per-pack price reductions available from different cigarette purchasing strategies: United States, 2009–2010. Prev Med. 2014;63(pm4, 0322116):13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tattan-Birch H, Brown J, Jackson SE. ‘Give ‘em the vape, sell ‘em the pods’: Razor-and-Blades Methods of pod e-cigarette pricing. Tob Control. 2021. [cited April 12, 2021]. https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/03/24/tobaccocontrol-2020-056354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from studies and used for analysis, the data collection template, and the analytic code are available upon request from the authors.