Abstract

Carbon monoxide (CO) has long been considered a toxic gas but is now a recognized bioactive gasotransmitter with potent immunomodulatory effects. Although inhaled CO is currently under investigation for use in patients with lung disease, this mode of administration can present clinical challenges. The capacity to deliver CO directly and safely to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract could transform the management of diseases affecting the GI mucosa such as inflammatory bowel disease or radiation injury. To address this unmet need, inspired by molecular gastronomy techniques, we have developed a family of gas-entrapping materials (GEMs) for delivery of CO to the GI tract. We show highly tunable and potent delivery of CO, achieving clinically relevant CO concentrations in vivo in rodent and swine models. To support the potential range of applications of foam GEMs, we evaluated the system in three distinct disease models. We show that a GEM containing CO dose-dependently reduced acetaminophen-induced hepatocellular injury, dampened colitis-associated inflammation and oxidative tissue injury, and mitigated radiation-induced gut epithelial damage in rodents. Collectively, foam GEMs have potential paradigm-shifting implications for the safe therapeutic use of CO across a range of indications.

INTRODUCTION

Carbon monoxide (CO), an odorless and colorless gas, has long been recognized as a silent killer because of its strong affinity to hemoglobin (Hb). Carbon monoxide competitively displaces oxygen to form carboxyhemoglobin (COHb), thereby decreasing the body’s oxygen-carrying capacity. In general, if COHb reaches 50%, then it may result in coma, convulsions, depressed respiration, and cardiovascular status compromise or even fatal consequences. Conversely, at lower concentrations, CO acts as a gasotransmitter with beneficial properties akin to nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide and has been implicated in a range of diverse physiological and pathological processes. Carbon monoxide has well-established immunomodulatory effects exerted through the heme oxygenase-1 (Hmox1; HO-1) pathway, which is implicated in adaptive cellular responses to stressful stimuli and injury (1–5). Exogenous administration of CO has been beneficial for the treatment of many diseases in preclinical models, including cardiovascular disorders, sepsis and shock, acute lung, kidney and liver injury, infection, and cancer (6).

Given the demonstrated preclinical benefit, therapeutic CO delivery by the inhalation route has been evaluated in clinical trials (7, 8). Inhalational delivery, however, presents profound challenges because of the variability in patient ventilation, environmental safety concerns for patients and healthcare workers, and the need for large amounts of compressed CO gas in cylinders that pose a health hazard due to the potential for cylinder leak or rapid depressurization (9). Therefore, other methods of administration have been developed including CO-releasing molecules (CORMs) and COHb infusions (10, 11). These alternatives are limited either because of toxicity of transition metals or potency. An oral liquid with dissolved CO is also being developed to deliver CO primarily through the stomach and upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but the tunability of the formulation is unclear (12). Delivery through the GI tract is particularly promising because of the high diffusivity of CO across the epithelial barrier of the stomach and intestines (12). Moreover, the potential for local anti-inflammatory effects could enhance the application of CO for diseases affecting the GI mucosa.

The discipline of molecular gastronomy has inspired delectable gas-filled materials over the past 40 years (13). Chefs across the world, including F. Adriá, have used foams and meringues to capture unique tastes and textures that appeal to the senses. Using whipping siphons, hand blenders, and mixers, these culinary artists create a deluge of different froths including shaving cream–like billows or light delicate aerated foams (9, 13). The techniques from molecular gastronomy have seldom been translated for pharmacologic intent and provide a unique opportunity to enable delivery of CO and other gasotransmitters across the epithelium of the GI tract.

Here, inspired by molecular gastronomy, we present the development and preclinical evaluation of gas-entrapping materials (GEMs) for the delivery of CO through the GI tract. These simple systems were designed using Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–classified generally regarded as safe (GRAS) components to support rapid clinical translation. We tested our formulations in three small animal models associated with inflammation and oxidative stress–induced tissue injury: acetaminophen (APAP)–induced acute liver injury, experimental colitis, and radiation-induced proctitis (14–16). We also selected models based on reported efficacy of inhaled CO (17, 18). Foam GEMs delivered high therapeutic amounts of carbon monoxide locally and systemically and reduced inflammation-associated damage in each animal model. These foam GEMs offer alternative modalities for the delivery of CO, enabling a spectrum of safe, effective, and potent delivery methods for enhanced translatability.

RESULTS

Design and fabrication of GEMs

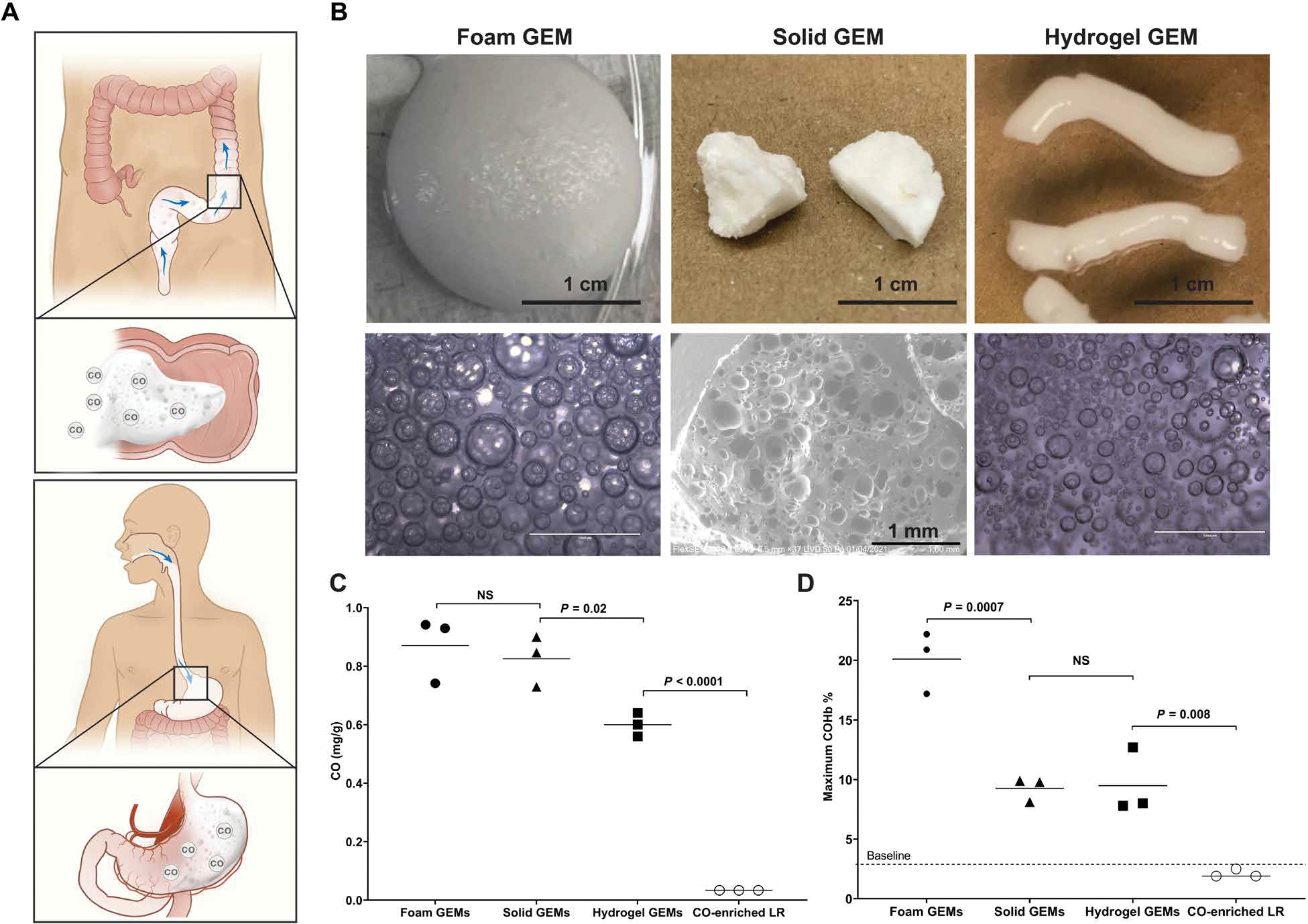

Pressurized vessels were used to physically entrap CO in GRAS materials that can be easily administered to the GI tract through the oral cavity or rectum (Fig. 1A). Specifically, whipping siphons were adapted to generate robust foams and hydrogels (Fig. 1B and figs. S1 and S2). The whipping siphons were rated for pressures near 500 psi, which provided a sufficiently large pressure range for operation. A custom-made high-pressure stirring reactor enabled the creation of solid gas–filled materials (Fig. 1B and figs. S1 and S3) in a process similar to that used for the candy, Pop Rocks. These pressurized vessels generated GEMs that can be rapidly dissolved based on the GEM composition and diluent (figs. S2 and S3). In particular, the solid GEMs rapidly dissolved in aqueous media, whereas the hydrogel GEMs used an EDTA solution to dissolve the ionic cross-linking.

Fig. 1. GRAS materials for GI delivery of CO.

(A) Schematic depicting oral and rectal routes of administration for GEMs. (B) Macroscopic and microscopic images of three GEMs, including foam GEMs, solid GEMS, and hydrogel GEMs. (C) Quantity of CO in each formulation compared to CO-enriched lactated Ringer’s solution (LR). (D) Maximum COHb achieved for each GEM administered through the GI tract. The foam GEMs were rectally administered (5 g/kg), and the solid GEMs (5 g/kg) and hydrogel GEMs (5 g/kg) were surgically placed in the stomach. The CO-enriched LR was administered via oral gavage (5 g/kg). The maximum COHb for solid GEMs was 30 min, hydrogel GEMs at 45 min, and foam GEMs at 15 min. Data are means (n = 3 mice per group). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. NS, not significant.

These materials were then evaluated using gas chromatography to quantify the amount of CO entrapped within the GEMs. The foam, solid, and hydrogel GEMs encapsulated about 25 times more CO than CO-enriched lactated Ringer’s (Fig. 1C) (19). Next, we evaluated the peak COHb percentages after a single GI administration of each GEM in mice; foam GEMs were given rectally, whereas the solid and hydrogel GEMs were placed in the stomach through a laparotomy at equivalent doses (5 g/kg). A single dose of these materials resulted in higher peak COHb percentages than those previously reported for GI formulations of CO (Fig. 1D and table S1) (10, 11, 17, 20–22). The pharmacodynamics of the GEMs demonstrated different CO exposures by each formulation (fig. S4). Given the maximum COHb and ease of rectal administration of the foams, the foams were further optimized and subsequently evaluated in experimental animal models of disease.

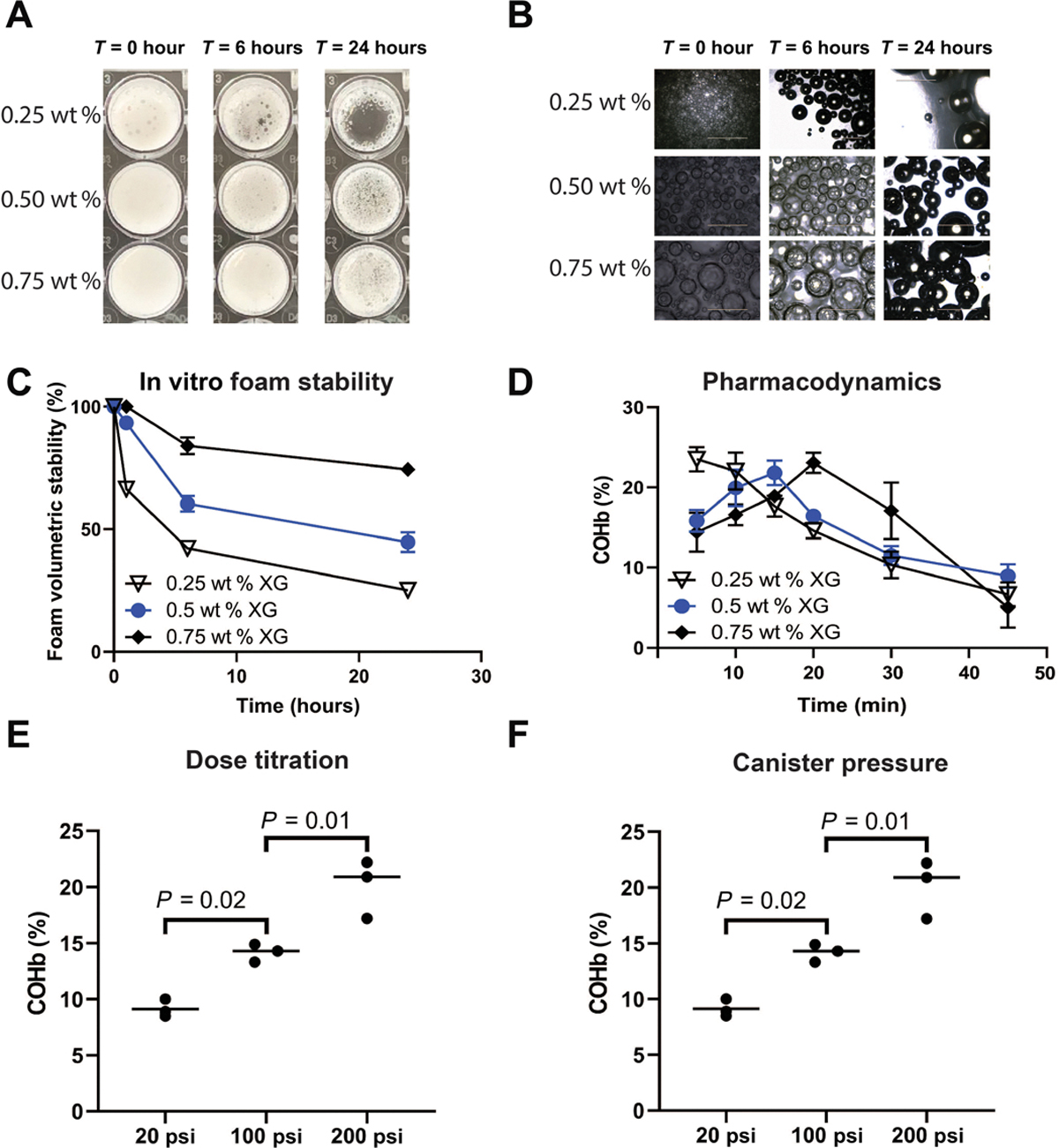

CO delivery optimization from rectally administered foams

Excipient concentrations, dosing, and pressure within the whipping siphon were evaluated to optimize CO delivery from foams. To study these parameters, we assessed visual differences in the macroscopic and microscopic appearance of the foams, volumetric foam stability, and CO release kinetics, as well as maximum COHb percentages in mice in vivo (Fig. 2 and figs. S4 to S6). Among the excipients within the foams, xanthan gum was found to have the greatest influence on foam stability (Fig. 2, A to C, and fig. S5). The higher the xanthan gum concentration, the more stable the foam and the more prolonged the COHb maxima; the 0.25 weight % (wt %) xanthan gum formulation was the least stable and showed the fastest COHb peak among the different formulations tested (Fig. 2, C and D, and fig. S6). Xanthan gum concentration had no influence on the amount of CO encapsulation (fig. S7). The COHb percentages were found to be directly correlated with dosing of the foams (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the amount of CO encapsulated in the foam GEMs increased with higher pressures within the whipping siphon (fig. S8). COHb percentages correlated with increasing pressures in the whipping siphon after a single rectal administration of equivalent dosing (5 g/kg; Fig. 2F). Benefits of the foams are long shelf life and the ability to formulate with other pharmaceutical agents (figs. S9 and S10). Last, rectal dosing of foams over multiple dosing schedules spanning hours and days show stability of COHb with no compounding effect observed with these regimens (fig. S11).

Fig. 2. Foam GEMs enable tunable delivery of CO.

(A) Photographs of foam stability in vitro at 0, 6, and 24 hours using different concentrations of xanthan gum (XG). (B) Representative images of foam GEMs with different concentrations of xanthan gum at 0, 6, and 24 hours. (C) Volumetric stability over 24 hours. (D) Pharmacodynamics of a single dose of rectally administered foam GEMs in mice over 45 min. Three foam GEMs with different concentrations of xanthan gum were evaluated and demonstrated different pharmacodynamics profiles (n = 5 mice per time point). (E) Carboxyhemoglobin after rectal administration in mice. (F) Carboxyhemoglobin as a function of canister pressure. Data are means (n = 3). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

We next evaluated the behavior of the foams under flow conditions. The foams behaved similar to viscoelastic solids, with storage moduli (G′) increasing with xanthan gum concentration and exceeding loss moduli (G″) for all formulations (fig. S12A). In addition, all formulations were highly shear thinning, indicative of their ease of deployment with spraying or injection (fig. S12, B and C). The 0.5 wt % xanthan gum foam was able to rapidly alternate between flowable and solid-like behavior at high and low shear strains, respectively (fig. S12D), and was therefore chosen for further testing in small and large animals.

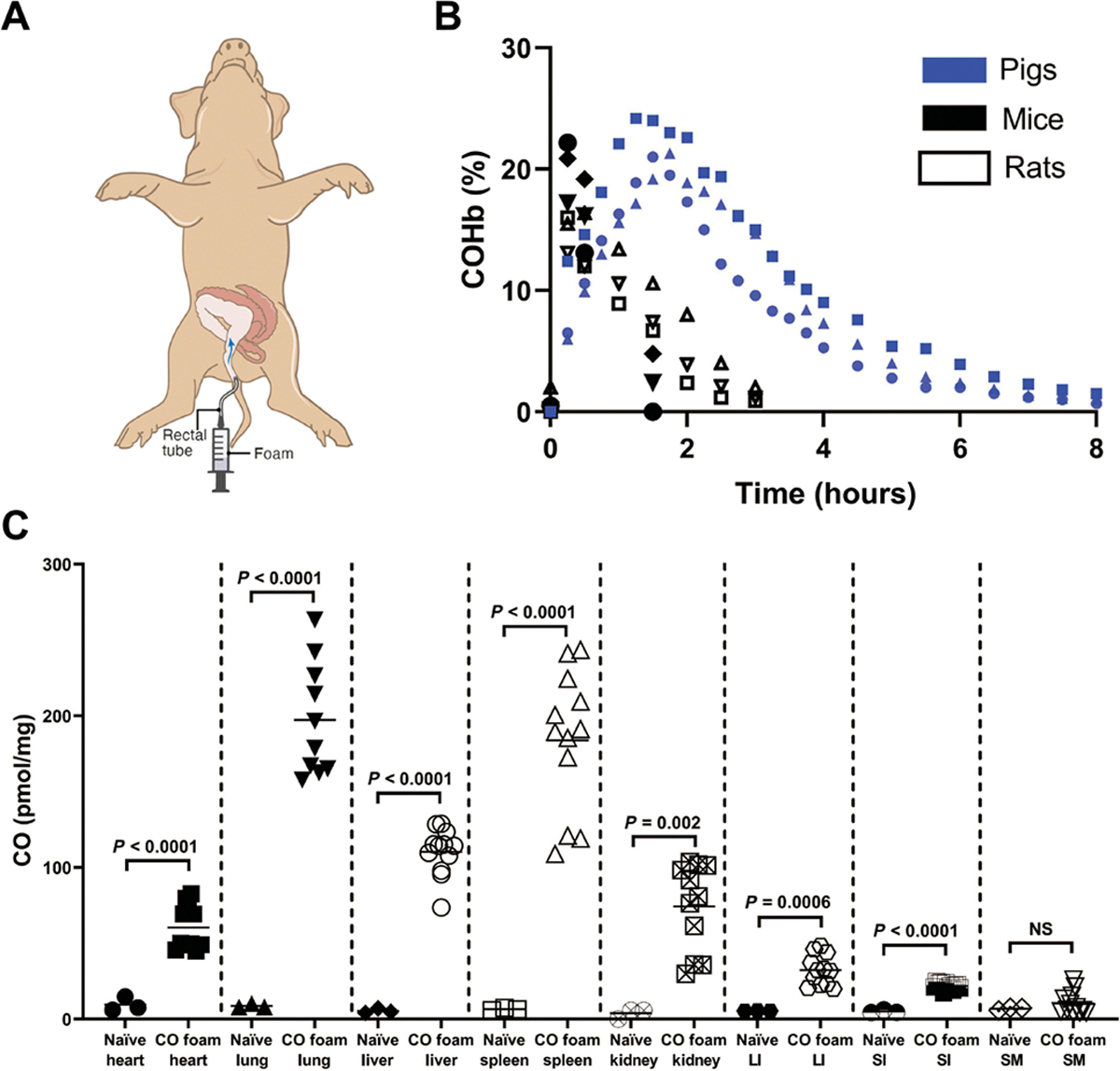

Characterization of local and systemic delivery of CO in small and large animals

The pharmacokinetics of rectal administration of CO-GEMs (5 g/kg) were characterized in both small and large animals (Fig. 3, A and B). COHb percentages in mice and rats reached a maximum directly after foam administration and rapidly decreased over 2 hours, paralleling the half-life observed with inhaled CO (23). Similarly, COHb percentages increased in nonventilated-anesthetized pigs over 2 hours after a single dose was administered intrarectally. Intestinal amounts of CO were higher for rectal foams (5 g/kg) compared to inhaled CO [250 parts per million (ppm) for 1 hour] (fig. S13).

Fig. 3. CO-GEMs achieve sustained, elevated COHb percentages in small and large animals.

(A) Schematic of rectal administration of foam to swine. (B) COHb percentages in mice, rats, and swine after rectal foam GEM administration (n = 3 animals per group). (C) Organ-specific concentrations of CO at 15 min after foam administration intrarectally in mice (5 g/kg). Data are means (n = 4 animals per arm, with each sample evaluated in triplicate as represented by a circle, square, or triangle). P values were determined by unpaired t test. LI, large intestine. SI, small intestine. SM, skeletal muscle.

Tissue amounts of CO were determined in mice that were rectally administered foam GEMs (Fig. 3, B and C). Greater amounts of CO were detected in multiple tissues 15 min after administration, particularly blood-filled organs that included the liver, heart, spleen, lungs, and kidney. The small and large intestines were also found to have higher CO amounts compared to naïve controls.

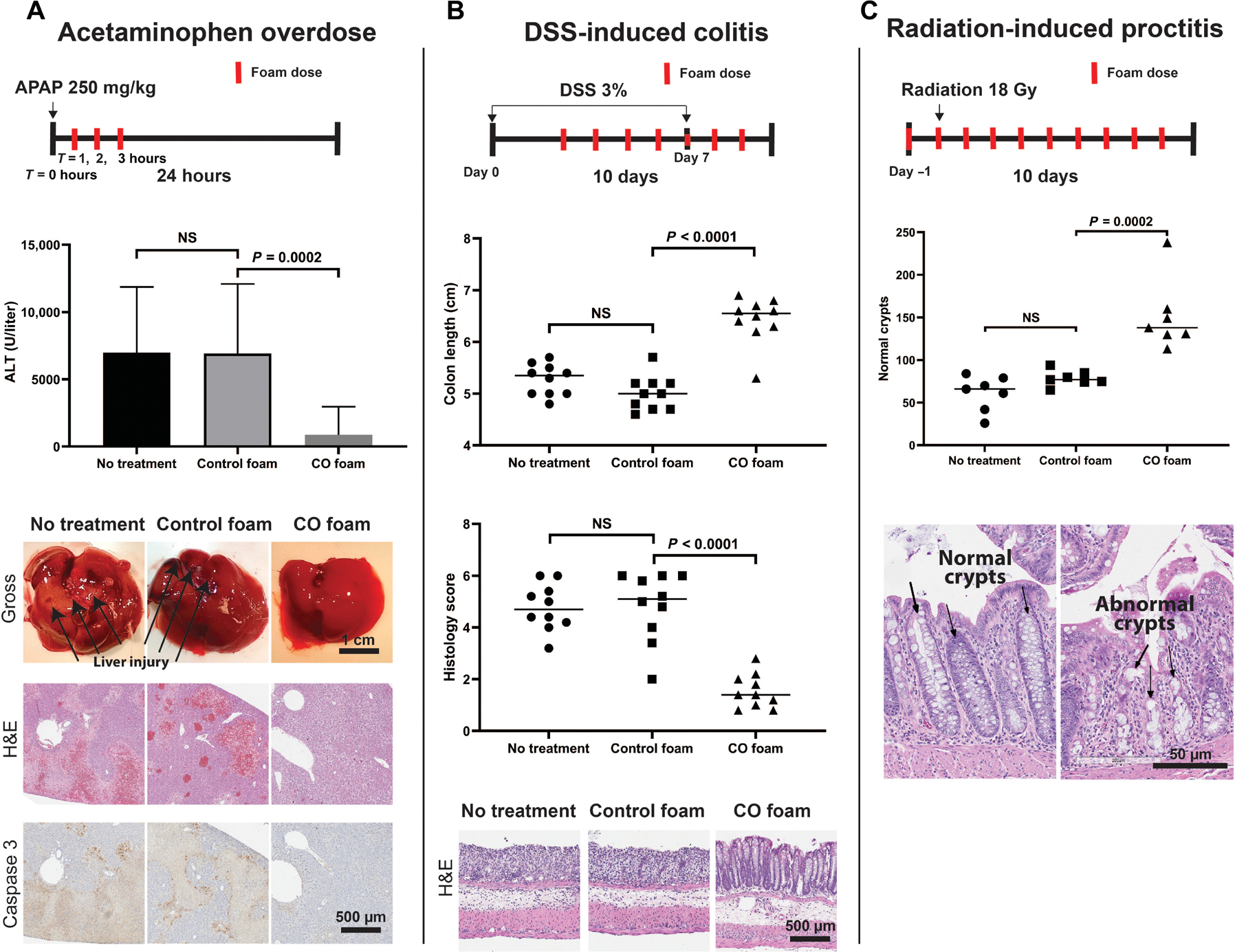

Rectal delivery of foam GEM inhibits APAP-induced hepatocellular injury

To characterize the efficacy of foam GEMs on dampening inflammatory responses in a disease model, we tested the foams in a well-characterized APAP overdose model (18, 24). In this model, fasted mice administered APAP intraperitoneally showed an expected radical-mediated hepatocyte cell death and a rapid proinflammatory response, resulting in acute liver failure. Mice were dosed with foam GEMs 1 hour after APAP and then hourly for a total of three doses (Fig. 4A). These animals were compared to control mice that received air GEM or no treatment. Animals that received foam GEM were found to have a dose-dependent reduction in hepatocellular injury as measured by serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentration compared to controls that received air GEM or no treatment (Fig. 4A and fig. S14). Reduced ALT concentrations were associated with less caspase 3 staining, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed reduced apoptosis, liver necrosis, and congestion compared to controls (Fig. 4). Liver from foam GEM–treated mice appeared histologically normal compared to controls. Collectively, these data demonstrate the protective effects of a foam GEM in preventing APAP-induced centrilobular congestion, hepatocellular degeneration, and coagulative necrosis.

Fig. 4. Rectally administered GEMs reduce inflammation in vivo.

(A) Schematic of experimental timeline. CO-GEMs (5 g/kg) was administered to mice at 1, 2, and 3 hours after injection of APAP (250 mg/kg, i.p.) to cause acute liver failure. ALT was assessed 24 hours after APAP. Controls included no treatment and air-GEM (P < 0.0001). Data represent means (n = 15 to 17 per arm). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Histopathology of liver sections showing hepatocyte cell death in controls (air-GEM, naïve) as measured by activated caspase 3 and H&E staining compared to liver sections from mice treated with APAP and CO-GEMs showed less activated caspase 3 and normal architecture. (B) In a model of DSS-induced experimental colitis, foam GEMs (5 g/kg) were administered to mice beginning on day 3 after DSS treatment was started and then daily for 10 days. Colon length and histology scores of DSS-treated animals administered CO-GEMs were compared to air-GEM and no treatment. H&E staining of liver tissue is shown below. Data represent means (n = 10 per arm). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. (C) In a model of radiation-induced proctitis, rats were treated with CO-GEMs rectally 1 day prior (5 g/kg), within 1 hour before irradiation (5 g/kg), and once daily for 8 days (5 g/kg) after exposure to 18 Gy of radiation directed to the rectum. H&E staining of rectal tissue depicts the quantity of normal intestinal crypts in animals treated with CO-GEMs was compared to no-treatment and air-GEM–treated control rats. Data represent mean (n = 7 per arm). P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

Rectally administered foam GEMs protect against experimental colitis

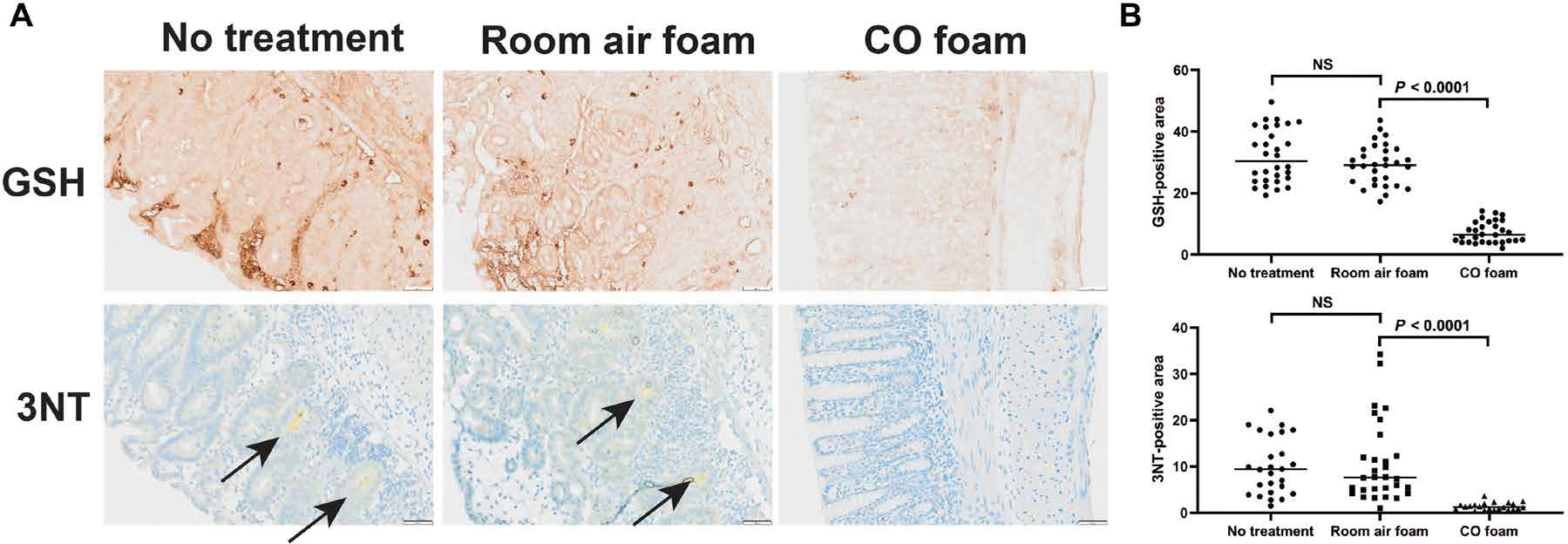

GEMs were next evaluated in the well-described experimental model of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)–induced colitis in mice. In this model, mice were exposed to DSS for 3 days to induce colitis before initiation of CO foam treatment. Animals were maintained on DSS-containing water, and GEMs (air or CO) were administered once a day for an additional 4 days. DSS water was then stopped, and daily administration of foam GEM, air GEM, or no treatment was continued for an additional 3 days (Fig. 4B). Foam GEM–treated mice showed reduced inflammation and tissue injury as evidenced by inhibition of DSS-induced colonic length shortening and reduced histological scores (Fig. 4B). Further analyses showed reduced crypt injury, edema, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils seen by histological staining (Fig. 4B). Staining for 3-nitrotyrosine (3NT) adduct as a marker of oxidative damage to proteins mediated by peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and glutathione-adducted proteins, common markers of oxidative stress, showed increased oxidation of proteins in the large intestine in animals treated with air GEM or DSS controls. This increase in expression of oxidative stress markers was significantly suppressed in foam GEM–treated mice (Fig. 5) (25, 26). In addition, analyses of the intestinal microbiome using 16S sequencing showed increased presence of Romboutsia and Muricomes spp. in CO-GEM–treated animals compared to controls (fig. S15) and may represent a mechanism by which CO limits intestinal injury and promote healing as reported by (27). These data support the therapeutic benefits of CO in limiting tissue damage in the colon after injury.

Fig. 5. CO-GEMs reduce DSS-induced increases in protein oxidation in large intestine in mice.

(A) In the model of DSS-induced experimental colitis, foam GEMs were administered to mice beginning on day 3 of DSS treatment and daily until day 10, and the tissues were collected, fixed with formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Representative images of large intestine stained for glutathione (GSH)–adducted proteins under nonreducing conditions and 3-nitrotyrosine (3NT) are shown as markers of oxidative damage. Arrows point to foci of 3NT within the large intestine. (B) Quantification of GSH-adducted proteins and 3NT-positive areas analyzed from randomly selected 600 μm by 600 μm sections of full thickness tissue (×8 magnification). Data represent means (n = 10 mice per arm, three replicates per mouse). P values were determined by unpaired t test.

CO-GEMs reduce crypt injury in radiation-induced proctitis model

The efficacy of CO-GEMs in dampening inflammation and tissue damage was next evaluated in a radiation-induced proctitis model. Rats were administered a single 18-Gy dose of radiation previously shown to induce acute proctitis within 2 weeks (28). Doses of this magnitude are routinely used for cancer therapy within the pelvis for definitive or palliative intent (29, 30). Compared to air GEM and no-treatment controls, CO-GEMs administered rectally before and after radiation resulted in a reduction in intestinal crypt injury (Fig. 4C). Moreover, there was a twofold increase in the number of normal crypts in rats treated with CO-GEMs compared to both air-GEMs and no treatment. Weight gain was similar among all groups (fig. S16).

DISCUSSION

The highly permeable nature of the GI tract epithelium allows for rapid absorption of gases, thereby positioning it as an attractive delivery pathway for the therapeutic use of CO. However, the translation of therapeutic gases from basic research into everyday treatments has remained a challenge due to numerous safety and dosing constraints (31). To address this problem, we physically entrapped CO gas in GRAS materials for delivery across the GI epithelium and termed them as GEMs. The physical methods of entrapment were inspired by existing technologies currently used in the culinary arts (32). Because of their ease of use, the GEM systems may be adapted to a variety of gasotransmitters, such as oxygen, nitric oxide, and hydrogen sulfide, for various disease-related applications.

Here, we showed that administration of CO through foam, solid, and hydrogel GEMs can deliver titratable amounts of CO locally and systemically. We demonstrated that formulations enabling the administration of CO through noninhaled routes are tunable and not limited by delivery materials, toxicity, or potency. Our preclinical results suggest that delivery of CO through these materials is dose dependent and tunable and very amenable to rectal administration. Our results confirm the benefits of CO in part through direct modulation of tissue free radicals and secondary oxidative species that not only contribute to tissue injury but also elucidate a new potential mechanism involving effects on intestinal commensal bacteria, including CO-induced increases in Romboutsia spp., a taxon known to be decreased in patients with Crohn’s disease (33). Although CO-specific global microbiome diversity changes were not detected, alterations among select taxa may provide additional benefit of the CO foams in DSS-induced colitis and is the focus of ongoing experimentation. In addition, our systems are amenable to coadministration with other therapies to improve treatment efficacy, such as in concert with powdered drug formulations.

Carbon monoxide has well-established cytoprotective effects first identified through studies of HO-1, which is implicated in adaptive cellular responses to stressful stimuli and injury (1–5). Administration of CO can mimic the benefits of inducing HO-1 activity and thus endogenous CO generation during heme catalysis. This enzymatic function of HO-1 naturally produces CO endogenously that regulates a variety of intra- and extracellular cytoprotective and homeostatic effects (6, 34). Although CO has been shown to be beneficial for multiple disease states, it may be particularly well suited for use in regulating GI inflammation because the dense capillary network of the intestinal mucosa allows for rapid, direct delivery and uptake of CO for remote organ effects such as the liver (35). In addition, HO-1 has been shown to play a key role in modulating intestinal inflammation and innate immunity, and activation of this pathway through delivery of CO has already demonstrated benefit in the treatment of intestinal disease in animal models of colitis (17, 36). Because of our ability to locally deliver CO, our GEMs could expand treatment options for other inflammatory pathologies of the GI tract that involve chronic oxidative stress and tissue damage, such as inflammatory bowel diseases, radiation-induced injury, colon cancer, and gastroparesis (37–40). Moreover, GI administration per os or per rectum can provide simpler and potentially more effective modalities of administering CO for the management of non-GI disorders given the high diffusivity of CO. Ingestion of CORMs or CO-saturated solutions have been shown to effectively treat sickle cell anemia, ischemia-reperfusion injury of the kidney, and prevention of gastric ulcer formation (12, 41–44). The challenges associated with these treatment strategies are potency and safety.

Although we achieved improvement in multiple small animal models of inflammation-mediated disease with these GEMs, the efficacy of these materials may be further improved by manipulating the materials to increase CO content or expand the utility of this approach with other gases such as nitric oxide or hydrogen sulfide. The pressure in the whipping siphons used to create foam and hydrogel GEMs was less than half of the pressure rating. Thus, increasing the pressure may further enhance entrapment of CO, thereby maximizing loading efficiency and reducing the volume of material needed to be delivered to achieve a therapeutic benefit. Alternative materials beyond those tested here may enhance the volume fraction of the gas, which would also reduce the total dosing volume. Although rectal delivery of the foams was evaluated, oral delivery of the foam, solid, and hydrogel GEMs may increase the translatability of the materials given the ease and comfort associated with oral administration. Moreover, the materials enable tunable release of CO that could broaden the number of disease indications for which GEMs may be effective.

Further research is required to better understand the safety and tolerability of GI delivery of CO. The FDA placed a maximum safe COHb of 14% for inhalational CO; however, it is possible that GI delivery may enable a different therapeutic index for CO delivery based on differing pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (10). There are reports that route of administration leads to marked differences in toxicology. Insufflation of the abdomen of dogs with CO to achieve COHb percentages comparable to CO administered by inhalation showed no toxicity as otherwise seen in dogs that inhaled CO (45). This strongly supports investigating alternative modes and routes of CO administration. Understanding person-to-person variability of COHb achieved between delivery modalities will be important to ensure patient safety and to maximize therapeutic benefit (31). Last, toxicity evaluation of the different materials and CO release kinetics will help determine safe formulation candidates to advance clinically.

For clinical translation of the GEMs, testing of these materials in large animal disease models will help determine the effectiveness in animals that more closely approximate the human condition. Our swine data confirm similar pharmacokinetics and feasibility for further translation into humans. Upon successful GEM optimization as a means to dampen the inflammatory response in large animal models, we will next evaluate these materials in healthy individuals to determine appropriate dosing, safety, and stability. Manufacturing of individual delivery devices that are recyclable and scalable will be required to facilitate safe handling for use in hospitals, clinics, in the field in ambulances, and helicopters as well as for in-home use.

Given the broad therapeutic benefits of CO, the GEMs described may be adopted for not only many different clinical applications, particularly inflammation-mediated GI conditions, but also pathologies as diverse as cancer, ileus, trauma, and organ transplant, among others (10). Furthermore, these materials could be extended to concomitant delivery of other pharmacologic agents for synergistic benefit, such as analgesics or antibiotics. In summary, our innovative approach using safe materials will offer modalities for the administration of therapeutic gases and treatment of acute and chronic inflammatory disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The overall goal of this work was to develop a simple, translational method for delivery of CO through the GI tract and to test in models of acute inflammation. We generated the GEMs using pressurized systems and assessed the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of these materials in normal healthy mice, rats, and swine (n = 3 to 5 mice per group). Upon identifying the COHb from GEMs, we selected a single GEM and tested the impact of CO exposure through GI administration of the GEM on liver injury in a mouse model of APAP overdose (n = 15 to 17 mice per arm), colitis in a chemical-induced mouse colitis model (n = 10 mice per arm), and rectal injury in a radiation proctitis rat model (n = 7 rats per arm). Investigators and animal technicians were not blinded to arms of the study. The pathologist was blinded before and during histological analysis. No animals were excluded from analysis. Each study was replicated two to four times, and the data described here are biological replicates of a single study.

Formulation development

To generate the foam GEMs, a prefoam solution was created by dissolving 0.5 wt % xanthan gum (Modernist Pantry), 0.8 wt % methylcellulose (Modernist Pantry), and 1.0 wt % maltodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and heating to 100°C while stirring at 700 rotations per minute. The solution was cooled to room temperature and placed under vacuum to degas for 12 hours. The solution was then placed into a modified iSi 1 Pint 100 stainless steel whipping siphon with a custom-made aluminum connector to enable pressurization with any gas cylinder, including carbon monoxide and room air. The aluminum connector was fabricated using a lathe to cut the part to size, and threads were created using an M22 tap and ¼ NPT die (fig. S1). The whipping siphon was purged with carbon monoxide before pressurizing up to 200 psi with 99.3% carbon monoxide (Airgas). The whipping siphon was then shaken for 30 s before use and actuated into a syringe.

The hydrogel GEMs were generated using a prefoam solution consisting of 1.0 wt % alginate (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25 wt % xanthan gum, 0.8 wt % methylcellulose, and 1.0 wt % maltodextrin dissolved in 1× PBS and heated to 100°C. The cooled prefoam solution was degassed for 12 hours and then placed into the modified whipping siphon. The hydrogels were cross-linked by actuating the foam into 100 mM calcium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) solution and subsequently removed.

The solid GEMs were formulated using a custom-fabricated high-pressure stirring reactor. A sugar solution was generated by dissolving 42.6 wt % sucrose, 42.6 wt % lactose, and 15.2 wt % corn syrup in water and heated to 132°C while stirring. The viscous sugar solution was placed in the high-pressure reactor heated to 135°C, the vessel was closed, and the pressure was increased to 600 psi of 99.3% CO. The system was stirred at 750 rotations per minute for 5 min. Subsequently, the pressure was increased to 650 psi, and the vessel rapidly cooled using ice water and allowed to sit for 30 min. The solid GEMs were removed and stored with a desiccant at room temperature.

Material characterization

The materials were initially characterized macroscopically and microscopically. Bubbles in the foam and hydrogel GEMs were studied using an EVOS microscope at ×10 magnification. The solid GEMs were cut using a razor blade and visualized using a Hitachi FlexSEM 1000 II scanning electron microscope. Bubble size distribution was assessed on the foams by placement of 1 ml of foam in a 24-well plate and performing serial microscopy at designated times to assess the bubble size. Furthermore, foam volumetric stability studies involved placement of 100 ml of foam into a 250-ml graduated cylinder, which were maintained in a humidified chamber at 37°C. The foam volume and liquid volume fractions were recorded after visual inspection at designated times.

CO quantification in the materials was performed using an Agilent gas chromatography–thermal conductivity detector (GC-TCD). Samples were evaluated in borosilicate glass GC vials that underwent three vacuum-nitrogen purge cycles before use. Foam samples were placed in vials after vacuum-nitrogen purge cycles and allowed to shake at 37°C for 24 hours to release CO completely. Solid GEMs were placed in vials before vacuum-nitrogen purge cycles, and 1 ml of deionized water was added to dissolve the solid GEMs; hydrogel GEMs were placed in vials before vacuum-nitrogen purge cycles, and 1 ml of 0.5 M EDTA solution was added to dissolve the hydrogels. The samples were subsequently run in triplicate on the GC-TCD. Calibration curves were generated using the same 99.3% CO cylinders used to generate each GEM.

Rheology measurements were performed on a TA Instruments DHR-3 Rheometer using 40-mm parallel plates. All measurements were conducted at 37°C with data averaged over three samples. Frequency sweeps were conducted at 1% strain, and amplitude sweeps at 10 rad/s.

Animal studies

All procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Care at MIT (protocol no. 0519–023-22, radiation protection), by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee at BIDMC [protocol no. 106–2015 (APAP) and protocol no. 068–2015 (DSS colitis)], and by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa (protocol no. 1092429–008, therapeutic foams), before initiation and all procedures described here, conform to the committee’s regulatory standards. The mice used in this study were 7- to 8-week-old male CD-1 or C57BL6/J mice, and rats were 8-week-old female Sprague-Dawley rats. Experiments were conducted at MIT Koch Institute animal facilities and BIDMC after at least 72 hours (rodents) and 7 days (swine) of acclimation. The swine used in this study were healthy female Yorkshire pigs between 65 and 80 kg. Animals were exposed to a 12-hour light/dark cycle and received food and water ad libitum through the studies, except when designated for experiments.

Evaluation of pharmacokinetics of CO

Isoflurane-anesthetized mice and rats were rectally administered foams through a 5-ml syringe attached to polyethylene tubing (1.2 mm in optical diameter) with tubing inserted ~1.5 cm. In addition, isoflurane-anesthetized swine were rectally administered foams through an inflated Electroplast SA pediatric rectal tube inserted 5 cm. In mice, blood was obtained from a lethal cardiac puncture under anesthesia; in rats, blood was obtained via tail vein; and in swine, blood was obtained from a central line accessing a jugular vein. All blood was placed into 1-ml BD syringes filled with 100 U of heparin and run on ABL80 FLEX CO-OX blood gas analyzer. For assessment of solid and hydrogel GEMs, isoflurane-anesthetized mice underwent a laparotomy with gastric incision for direct placement of preweighed materials (5 g/kg) into the stomach. Animals underwent a cardiac puncture at 15 min after direct placement of solid and hydrogel GEMs, and blood was collected in 1-ml syringes filled with 100 U of heparin and run on the ABL80 FLEX CO-OX blood gas analyzer. Heparinized blood and tissues were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen for analysis.

Methods for CO extraction and quantification from tissues followed previously established methods (46, 47). The quantity of CO extracted from the blood and tissue samples was measured using a reducing compound photometer GC system (GC Reducing Compound Photometer, Peak Performer 1, Peak Laboratories LLC). A certified calibration gas (1.02 ppm CO balanced with nitrogen) was purchased from Airgas and used to generate a daily standard curve before experiments. Amber borosilicate glass chromatography vials (2 ml) with gas-tight silicone septa were used for all experiments and were purged of CO using a custom catalytic converter before the addition of calibration gas or samples. The vial headspace was flushed with CO-free carrier gas into the gas chromatography system via a custom-made double-needle assembly attached to the front of the instrument.

Frozen aliquots of heparinized whole blood stored in sealed cryovials were thawed, and 1 μl was injected into a purged amber chromatography vial along with 20 μl of K3Fe(CN)6 using gas-tight syringes attached to repeating dispensers (Hamilton). The contents in the vial were mixed thoroughly and stored on ice for a minimum of 15 min before CO analysis. Blood CO quantitation was reported as VolCO, the amount of CO (in milliliters) bound to 100 ml of whole blood. Hb concentration (in grams per deciliter) was determined with the cyanmethemoglobin method using Drabkin’s reagent (RICCA Chemical Company, Arlington, TX). A standard curve was generated using a commercially available Hb standard (Pointe Specific H7506STD, Canton, MI). The VolCO and Hb concentration values were used to calculate the COHb using the following equation: COHb (% sat) = [(Vol)CO × 100%/([Hb] × 1.34)]. Mouse tissues were rinsed gently of external blood with chilled KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.4) and placed into 50-ml conical tubes. Tissues were diluted to 10% (w/w) with water. With the tube submerged in ice, the tissue was diced with surgical scissors then homogenized using the Ultra-Turrax T8 grinder (IKA Works Inc., Wilmington, NC) for six to eight 1-s pulses, followed by 8 to 10 1-s pulses from an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Branson, Danbury, CT). Once completely homogenized, 10 μl of tissue homogenate and 20 μl of 20% sulfosalicylic acid were injected into the purged 2-ml amber vials with a gas-tight syringe connected to a repeating dispenser. Once injected, vials were treated as described above. CO values were reported as CO (in picomol) per milligram wet weight tissue.

Efficacy studies

APAP overdose mouse model

Male CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories) were fasted for 18 hours to deplete hepatocytic glutathione concentrations and then subsequently intraperitoneally injected with APAP (Sigma-Aldrich) at 250 mg/kg (18). The mice were randomized into the different conditions (n = 15 to 17 per arm), including experimental (CO foam rectally administered at 5.0, 2.5, 1.0, and 0.5 g/kg) and controls (room air control foam rectally administered at 5 g/kg and no treatment). One hour after the intraperitoneal dose of APAP, mice under isoflurane were treated every hour for 3 hours with CO foam, room air control foam, or no treatment. The mice were euthanized 24 hours after the intraperitoneal injection, and serum and livers were collected for evaluation. ALT analysis was performed using a Catalyst DX from IDEXX. The tissues were subsequently formalin-fixed, processed, H&E-stained, and immunohistochemically stained for caspase 3.

DSS colitis

Male C57BL/6 mice (Taconic Biosciences) were randomized into the different conditions (n = 10 per arm), including experimental (foam GEMs rectally administered at 5 g/kg) and controls (room air control foam rectally administered at 5 g/kg and no treatment). Mice were administered 3 wt % DSS water continuously on days 1 to 7. Starting on day 3, the mice were rectally administered CO foam, room air control foam, or no treatment under isoflurane. Mice were weighed daily before treatment and assessed for signs of morbidity. If there was greater than 20% weight loss, then the mice were euthanized, and the large intestines were collected and measured. The tissues were subsequently formalin-fixed, processed, and H&E-stained. H&E sections were scored in a blinded fashion.

Radiation-induced proctitis

Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) were randomized into CO foam, room air control foam, and no treatment (n = 7 per arm). One day before irradiation, the rats were anesthetized using 1 to 3% isoflurane and administered rectal foams (5 g/kg). Within 1 hour before irradiation, the rats were rectally administered a dose of foam (5 g/kg). For irradiation, rats were anesthetized using 1 to 3% isoflurane with room air and monitored using pulse oximetry. Rats were exposed to 18 Gy directed to the rectum from a single x-ray radiation source from an X-RAD 320. The rats were then rectally administered CO foam, air control foam, or no treatment under isoflurane daily up until euthanasia. After completion of radiation, the animals were evaluated twice daily. Any animal that exhibited signs of morbidity or weight loss was administered buprenorphine. The animals were euthanized 9 days after completion of radiation, and tissue was formalin-fixed, processed, and H&E-stained. Outcome measures were defined as an extent of radiation-induced rectal injury defined as crypt injury.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Graphs were created with GraphPad Prism software. All analyses were done using SAS v9.3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) methods were used for multiple comparisons of continuous values between three and more groups. Unpaired t tests were used to analyze two groups. Unadjusted P values were reported for pairwise comparisons when an overall difference was detected. To compare the mass of CO per mass of material between different materials, ANOVA tests were used, and exact nominal P values were reported, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank A. Hupalowska for illustrations, B. Krasnow from the Applied Science YouTube channel for fabrication of the high-pressure stirring reactor, and C. Unger from the MIT Hobby Shop for welding of a stir rod. We thank M. Jimenez for discussions. We also thank the BIDMC, MIT Koch Institute, and University of Iowa Orthopedic Histopathology cores for rapid and detailed work on the histology.

Funding:

This work was funded in part by grants from the following: the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award, Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Program Early Investigator Award, Hope Funds for Cancer Research fellowship, and Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Iowa (to J.D.B.); the National Science Foundation 1927616 (to M.T.); the Players Association of the National Football League and Department of Defense W81XWH-16–0464 (to L.E.O.); the Department of Mechanical Engineering, MIT (to G.T.); and the National Institutes of Health grants R00AR070914 (to M.C.C.), R01DK108894 and R01DK124408 (to M.S.L.), and P01CA217797 and P30CA086862 (to D.R.S.).

Footnotes

Competing interests: L.E.O. is a scientific advisor to Hillhurst Biopharmaceuticals. J.D.B., D.G., H.B., L.E.O., and G.T. are co-inventors on a patent application (WO2022055991A1) submitted by Brigham and Women’s Hospital, MIT, and BIDMC that covers therapeutic carbon monoxide formulations. C.S. is an employee of Bayer AG and is co-inventor of multiple patents and patent applications describing carbon monoxide delivery systems. Complete details of all relationships for profit and not for profit for G.T. can found at www.dropbox.com/sh/szi7vnr4a2ajb56/AABs5N5i0q9AfT1IqIJAE-T5a?dl=0. Complete details for R.L. can be found at www.dropbox.com/s/yc3xqb5s8s94v7x/Rev%20Langer%20COI.pdf?dl=0. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Materials are available upon request through the corresponding authors.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Otterbein LE, Lee PJ, Chin BY, Petrache I, Camhi SL, Alam J, Choi AM, Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest 116, 61S–63S (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soares MP, Lin Y, Anrather J, Csizmadia E, Takigami K, Sato K, Grey ST, Colvin RB, Choi AM, Poss KD, Bach FH, Expression of heme oxygenase-1 can determine cardiac xenograft survival. Nat. Med. 4, 1073–1077 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryter SW, Choi AM, Cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory actions of carbon monoxide in organ injury and sepsis models. Novartis Found. Symp. 280, 165–175 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, Soares M, Tao Lu H, Wysk M, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Choi AM, Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat. Med. 6, 422–428 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM, Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol. Rev. 86, 583–650 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motterlini R, Otterbein LE, The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 728–743 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredenburgh LE, Perrella MA, Barragan-Bradford D, Hess DR, Peters E, Welty-Wolf KE, Kraft BD, Harris RS, Maurer R, Nakahira K, Oromendia C, Davies JD, Higuera A, Schiffer KT, Englert JA, Dieffenbach PB, Berlin DA, Lagambina S, Bouthot M, Sullivan AI, Nuccio PF, Kone MT, Malik MJ, Porras MAP, Finkelsztein E, Winkler T, Hurwitz S, Serhan CN, Piantadosi CA, Baron RM, Thompson BT, Choi AM, A phase I trial of low-dose inhaled carbon monoxide in sepsis-induced ARDS. JCI Insight 3, e124039 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosas IO, Goldberg HJ, Collard HR, El-Chemaly S, Flaherty K, Hunninghake GM, Lasky JA, Lederer DJ, Machado R, Martinez FJ, Maurer R, Teller D, Noth I, Peters E, Raghu G, Garcia JGN, Choi AMK, A phase II clinical trial of low-dose inhaled carbon monoxide in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 153, 94–104 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji X, Damera K, Zheng Y, Yu B, Otterbein LE, Wang B, Toward carbon monoxide-based therapeutics: Critical drug delivery and developability issues. J. Pharm. Sci. 105, 406–416 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magierowska K, Magierowski M, Surmiak M, Adamski J, Mazur-Bialy AI, Pajdo R, Sliwowski Z, Kwiecien S, Brzozowski T, The protective role of carbon monoxide (CO) produced by heme oxygenases and derived from the co-releasing molecule CORM-2 in the pathogenesis of stress-induced gastric lesions: Evidence for non-involvement of nitric oxide (NO). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 442 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belcher JD, Gomperts E, Nguyen J, Chen C, Abdulla F, Kiser ZM, Gallo D, Levy H, Otterbein LE, Vercellotti GM, Oral carbon monoxide therapy in murine sickle cell disease: Beneficial effects on vaso-occlusion, inflammation and anemia. PLOS ONE 13, e0205194 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishan L, T Magazine - The New York Times. (2019) Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 13.McLaughlin K, The Wall Street Journal 10, (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amrouche-Mekkioui I, Djerdjouri B, N-acetylcysteine improves redox status, mitochondrial dysfunction, mucin-depleted crypts and epithelial hyperplasia in dextran sulfate sodium-induced oxidative colitis in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 691, 209–217 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla PK, Gangwar R, Manda B, Meena AS, Yadav N, Szabo E, Balogh A, Lee SC, Tigyi G, Rao R, Rapid disruption of intestinal epithelial tight junction and barrier dysfunction by ionizing radiation in mouse colon in vivo: Protection by N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 310, G705–G715 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGill MR, Hinson JA, The development and hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen: Reviewing over a century of progress. Drug Metab. Rev. 52, 472–500 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiger C, Uchiyama K, Takagi T, Mizushima K, Higashimura Y, Gutmann M, Hermann C, Botov S, Schmalz HG, Naito Y, Meinel L, Prevention of colitis by controlled oral drug delivery of carbon monoxide. J. Control. Release 239, 128–136 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y, Ji X, Yu B, Ji K, Gallo D, Csizmadia E, Zhu M, Choudhury MR, De La Cruz LKC, Chittavong V, Pan Z, Yuan Z, Otterbein LE, Wang B, Enrichment-triggered prodrug activation demonstrated through mitochondria-targeted delivery of doxorubicin and carbon monoxide. Nat. Chem. 10, 787–794 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao A, Schmidt J, Harada T, Tsung A, Stoffels B, Cruz RJ Jr., Kohmoto J, Peng X, Tomiyama K, Murase N, Bauer AJ, Fink MP, A single intraperitoneal dose of carbon monoxide-saturated ringer’s lactate solution ameliorates postoperative ileus in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 1265–1275 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braud L, Pini M, Muchova L, Manin S, Kitagishi H, Sawaki D, Czibik G, Ternacle J, Derumeaux G, Foresti R, Motterlini R, Carbon monoxide-induced metabolic switch in adipocytes improves insulin resistance in obese mice. JCI Insight 3, e123485 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pena AC, Penacho N, Mancio-Silva L, Neres R, Seixas JD, Fernandes AC, Romao CC, Mota MM, Bernardes GJ, Pamplona A, A novel carbon monoxide-releasing molecule fully protects mice from severe malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1281–1290 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dingenen J, Steiger C, Zehe M, Meinel L, Lefebvre RA, Investigation of orally delivered carbon monoxide for postoperative ileus. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 130, 306–313 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson ES, Jones AB, Ashfaq MK, Barrett JT, Spectrophotometric evaluation of carboxyhemoglobin in blood of mice after exposure to marijuana or tobacco smoke in a modified Walton horizontal smoke exposure machine. J. Anal. Toxicol. 11, 19–23 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan M, Huo Y, Yin S, Hu H, Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver injury and its implications for therapeutic interventions. Redox Biol. 17, 274–283 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman MC, Goetz JE, Brouillette MJ, Seol D, Willey MC, Petersen EB, Anderson HD, Hendrickson NR, Compton J, Khorsand B, Morris AS, Salem AK, Fredericks DC, McKinley TO, Martin JA, Targeting mitochondrial responses to intra-articular fracture to prevent posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaan5372 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas DD, Espey MG, Vitek MP, Miranda KM, Wink DA, Protein nitration is mediated by heme and free metals through Fenton-type chemistry: An alternative to the NO/O2− reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12691–12696 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegazi RA, Rao KN, Mayle A, Sepulveda AR, Otterbein LE, Plevy SE, Carbon monoxide ameliorates chronic murine colitis through a heme oxygenase 1-dependent pathway. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1703–1713 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sezer A, Usta U, Kocak Z, Yagci MA, The effect of a flavonoid fractions diosmin + hesperidin on radiation-induced acute proctitis in a rat model. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 7, 152–156 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zilli T, Franzese C, Bottero M, Giaj-Levra N, Forster R, Zwahlen D, Koutsouvelis N, Bertaut A, Blanc J, Roberto D’agostino G, Alongi F, Guckenberger M, Scorsetti M, Miralbell R, Single fraction urethra-sparing prostate cancer SBRT: Phase I results of the ONE SHOT trial. Radiother. Oncol. 139, 83–86 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reshko LB, Baliga S, Crandley EF, Harry Lomas IV, Richardson MK, Spencer K, Bennion N, Mikdachi HE, Irvin W, Kersh CR, Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in recurrent, persistent or oligometastatic gynecological cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 159, 611–617 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopper CP, Meinel L, Steiger C, Otterbein LE, Where is the clinical breakthrough of heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide therapeutics? Curr. Pharm. Des. 24, 2264–2282 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myhrvold N, Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking (The Cooking Lab, ed. 1, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu X, Zhao X, Cui X, Mao X, Tang N, Jiao C, Wang D, Zhang Y, Ye Z, Zhang H, Characterization of fungal and bacterial dysbiosis in young adult Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 13, 1756284820971202 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R, The enzymatic conversion of heme to bilirubin by microsomal heme oxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 61, 748–755 (1968). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coburn RF, Carbon monoxide uptake in the gut. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 150, 13–21 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onyiah JC, Sheikh SZ, Maharshak N, Otterbein LE, Plevy SE, Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide regulate intestinal homeostasis and mucosal immune responses to the enteric microbiota. Gut Microbes 5, 220–224 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association, American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 127, 1592–1622 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neurath M, Current and emerging therapeutic targets for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 688 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shadad AK, Sullivan FJ, Martin JD, Egan LJ, Gastrointestinal radiation injury: Symptoms, risk factors and mechanisms. World J. Gastroenterol. 19, 185–198 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irrazabal T, Thakur BK, Kang M, Malaise Y, Streutker C, Wong EOY, Copeland J, Gryfe R, Guttman DS, Navarre WW, Martin A, Limiting oxidative DNA damage reduces microbe-induced colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 11, 1802 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Correa-Costa M, Gallo D, Csizmadia E, Gomperts E, Lieberum JL, Hauser CJ, Ji X, Wang B, Camara NOS, Robson SC, Otterbein LE, Carbon monoxide protects the kidney through the central circadian clock and CD39. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E2302–E2310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magierowski M, Magierowska K, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Sliwowski Z, Ginter G, Pajdo R, Chmura A, Kwiecien S, Brzozowski T, Carbon monoxide released from its pharmacological donor, tricarbonyldichlororuthenium (II) dimer, accelerates the healing of pre-existing gastric ulcers. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 3654–3668 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakalarz D, Surmiak M, Yang X, Wojcik D, Korbut E, Sliwowski Z, Ginter G, Buszewicz G, Brzozowski T, Cieszkowski J, Glowacka U, Magierowska K, Pan Z, Wang B, Magierowski M, Organic carbon monoxide prodrug, BW-CO-111, in protection against chemically-induced gastric mucosal damage. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 456–475 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takagi T, Naito Y, Uchiyama K, Mizuhima K, Suzuki T, Horie R, Hirata I, Tsuboi H, Yoshikawa T, Carbon monoxide promotes gastric wound healing in mice via the protein kinase C pathway. Free Radic. Res. 50, 1098–1105 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez G, Rotman HH, Reid CM, Dantzker DR, Comparison of canine cardiovascular response to inhaled and intraperitoneally infused CO. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 58, 558–563 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vreman HJ, Kwong LK, Stevenson DK, Carbon monoxide in blood: An improved microliter blood-sample collection system, with rapid analysis by gas chromatography. Clin. Chem. 30, 1382–1386 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vreman HJ, Wong RJ, Kadotani T, Stevenson DK, Determination of carbon monoxide (CO) in rodent tissue: Effect of heme administration and environmental CO exposure. Anal. Biochem. 341, 280–289 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Materials are available upon request through the corresponding authors.