Abstract

Objectives

We investigated serum neutralizing activity against BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron sublineages and T cell response before and 3 months after administration of the booster vaccine in healthcare workers (HCWs).

Methods

HCWs aged 18–65 years who were vaccinated and received booster doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine were included. Anti–SARS coronavirus 2 IgG levels and cellular response (through interferon γ ELISpot assay) were evaluated in all participants, and neutralizing antibodies against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 were evaluated in participants with at least one follow-up visit 1 or 3 months after the administration of the booster dose.

Results

Among 118 HCWs who received the booster dose, 102 and 84 participants attended the 1-month and 3-month visits, respectively. Before the booster vaccine dose, a low serum neutralizing activity against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 was detectable in only 39/102 (38.2%), 8/102 (7.8%), and 12/102 (11.8%) participants, respectively. At 3 months, neutralizing antibodies against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 were detected in 84/84 (100%), 79/84 (94%), and 77/84 (92%) participants, respectively. Geometric mean titres of neutralizing antibodies against BA.1 and BA.2 were 2.2-fold and 2.8-fold reduced compared with those for Delta. From 1 to 3 months after the administration of the booster dose, participants with a recent history of SARS coronavirus 2 infection (n = 21/84) had persistent levels of S1 reactive specific T cells and neutralizing antibodies against Delta and BA.2 and 2.2-fold increase in neutralizing antibodies against BA.1 (p 0.014). Conversely, neutralizing antibody titres against Delta (2.5-fold decrease, p < 0.0001), BA.1 (1.5-fold, p 0.02), and BA.2 (2-fold, p < 0.0001) declined from 1 to 3 months after the administration of the booster dose in individuals without any recent infection.

Discussion

The booster vaccine dose provided significant and similar response against BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron sublineages; however, the immune response declined in the absence of recent infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, Neutralizing antibodies, Omicron, T cells

Introduction

The Omicron (B.1.1.529) SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variant emerged in the late 2021 and rapidly outcompeted the already highly transmissible Delta variant.

The first sublineage of this variant, BA.1, became dominant in Europe between December 2021 and January 2022 and generated serious concern about the efficacy of vaccines owing to the substantial escape from neutralizing antibodies. Indeed, Omicron displayed numerous epitopic modifications of the spike protein, and because the available coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines were prepared with the original lineage, neutralizing activity against Omicron was absent or very low even in vaccinated people [1,2].

The subsequent sublineage BA.2 rapidly replaced the previous one in Europe around March 2022 to April 2022, and the rates of new sublineages BA.4 and BA.5 increased by June 2022 [3]. BA.2 has shown a selective advantage over BA.1, especially enhanced transmissibility, and can reinfect previously BA.1-infected individuals [4,5].

Recent data have shown that beyond 6 months after the primary vaccination course, neutralizing antibodies against Omicron sublineages were undetectable or at very low levels; however, neutralizing antibody titres increased significantly few weeks after the administration of booster vaccination (third dose) [[6], [7], [8]].

In this study, we evaluated the neutralizing antibody responses against BA.1 and BA.2 sublineages of the Omicron variant in parallel with the previous Delta variant in a cohort of healthcare workers (HCWs) who were vaccinated and received booster doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer–BioNTech). In addition, cellular responses to SARS-CoV-2 were investigated, and the occurrence of infection after the booster dose was analysed.

Methods

This study is part of the MONITOCOV-Aging project (Monitoring the immune response to BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in older people), in which the protocol amendments concerning the present data were approved by the Ile-De-France V (ID-CRB 2021-A00119-32) ethics committee.

HCWs were consecutively included in the study if they had no significant chronic disease and no medication that could influence their immune responses (including steroids and immunosuppressive therapies), and were aged 18–65 years. All participants initially received two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine at a 3-week dosing interval. The booster dose was administered to the participants in accordance with French national guidelines (at least 6 months after primary vaccination course). Data from the samples collected before and 3 months after the primary vaccination have been reported previously [9], and data from the samples collected before the administration of the booster as well as at 1 and 3 months after the administration of the booster doses are reported in this study.

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels and neutralizing antibodies (using a live virus neutralization assay) against Delta variant and BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron sublineages were evaluated. Cellular responses were evaluated through interferon γ ELISpot assay.

Please see supplementary material for detailed methods.

Results

A total of 118 individuals who received the booster dose were included. Samples were collected at 1 month after administration of the booster dose for 102 subjects, and only 84 participants attended the 3-month visit. The median (interquartile range) time between the initial vaccination (second dose) and the booster dose was 254 (248–265) days.

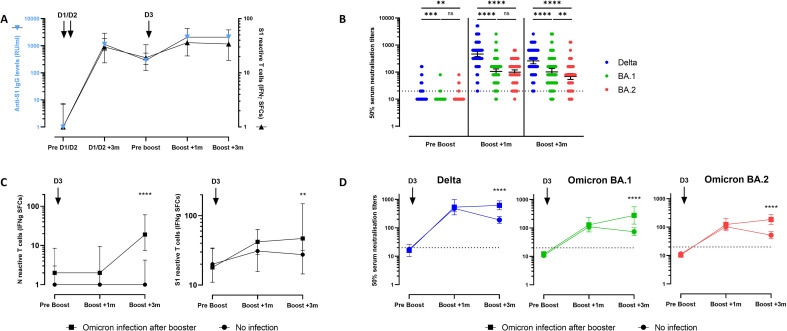

Three months after the primary vaccination course (doses 1 and 2), the median level (interquartile range) of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG was 1125 (653–1828) BAU/mL. This value declined to 290 (200–534) BAU/mL before the third dose and then peaked to more than 2080 BAU/mL 1 and 3 months after administration of the booster dose (Fig. 1 a). The counts of S1 reactive T cells also increased 1 and 3 months after administration of the booster dose (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Specific antibody and T cell response 1 month and 3 months after administration of the BNT162b2 mRNA booster vaccine. (a) Anti-S1 IgG levels (blue, left Y axis) and S1-specific reactive T cells (black, right Y axis) from before initial vaccination (before doses 1 and 2) to 3 months after administration of the booster vaccine dose. (b) Neutralization of the Delta, BA.1 Omicron and BA.2 Omicron variants before and 1 month and 3 months after administration of the booster BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine dose. Positive threshold (titre ≥20) is shown with a dotted line. Individual values, geometric mean neutralization titres, and 95% CIs are shown. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for within-subject comparisons. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. (c) Specific reactive T cells counts before and 1 month and 3 months after administration of the booster BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. Individual values and median (interquartile range) are shown. N (left panel) and S1 (right panel) specific reactive T cells in healthcare workers without (circle) or with (square) COVID-19 after administration of the booster dose. Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare T cell counts between both groups. ∗∗p 0.006; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. (d) Neutralization of the Delta, BA.1 Omicron, and BA.2 Omicron variants in healthcare workers without (circle) or with (square) COVID-19 after administration of the booster dose. Positive threshold (titre ≥20) is shown with a dotted line. Geometric mean neutralization titres and 95% CIs are shown. A mixed model analysis of variance was performed to compare both groups. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. IFN, interferon; ns, not significant; SFCs, spot forming cells.

As shown in Fig. 1b, before administration of the booster vaccine dose, serum neutralizing activity against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 was detectable in only 39/102 (38.2%), 8/102 (7.8%), and 12/102 (11.8%) participants, respectively, with low neutralizing antibody titres ranging from 20 to 160. Geometric mean titres (GMTs) were below the limit of detection of 20 for all variants.

One month after administration of the booster dose, a neutralizing activity against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 was observed in 102/102 (100%), 99/102 (97%), and 101/102 (99%) tested sera, respectively. In addition, the GMTs of neutralizing antibodies (95% CI) significantly increased to 465 (373–579) for Delta, 105 (85–131) for BA.1, and 99 (82–121) for BA.2, indicating that the GMTs against Delta were 4.4-fold and 4.7-fold higher than those against BA.1 (p < 0.0001) and BA.2 (p < 0.0001), respectively.

Three months after administration of the booster dose, neutralizing antibodies against Delta, BA.1, and BA.2 were detected in 100% (n = 84/84), 94% (n = 79/84), and 92% (n = 77/84) of the participants, respectively, and the GMTs were 260 (203–334), 102 (76–136), and 69 (54–88), respectively. GMTs against BA.1 and BA.2 were 2.6-fold and 3.8-fold reduced compared with those against Delta 3 months after administration of the booster dose (p < 0.0001 in both comparisons).

Within 3 months after administration of the booster dose, a SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed or strongly suspected in 21 subjects (presumably Omicron infections because this variant represented >95% of cases during this period). The infection was confirmed by a positive RT-PCR test result in ten individuals, with the infection occurring during the first 4 weeks (1 subject) or during the next 8 weeks (9 subjects) after administration of the booster vaccination. An asymptomatic infection, not confirmed by RT-PCR for this reason [10] and not detectable by serological tests using antigens from the spike protein, was strongly suspected in the remaining 11 individuals by a significant increase of N reactive specific T cells in the interferon γ ELISpot assay because the N protein is not an antigen targeted by BNT162b2 (Fig. 1c).

Subgroup analysis showed that 3 months after administration of the booster dose, S1 reactive specific T cells (Fig. 1c) and neutralizing antibody levels against all variants were higher in the group with a history of post–booster dose infection than in participants without recent infection (Fig. 1d and Table S1). Indeed, the GMT (95% CI) of neutralizing titres declined from 1 to 3 months after administration of the booster dose in individuals without any recent infection with the Delta (482 [366–635] vs. 190 [143–252]; 2.5-fold decrease; p < 0.0001), BA.1 (110 [85–142] vs. 74 [85–142]; 1.5-fold decrease; p 0.02), or BA.2 variant (104 [81–133] vs. 52 [39–69]; 2-fold decrease; p < 0.0001). Conversely, participants with a recent history of SARS-CoV-2 infection had persistent levels of S1 reactive specific T cells and neutralizing antibodies against Delta and BA.2, and neutralizing antibodies against BA.1 increased from 128.5 (72–229) to 277 (137–557) (2.2-fold increase; p 0.014). (Fig. 1d and Table S1).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the vaccine-induced response against Omicron sub-variants. We found that 8.5 months (median) after the primary vaccination course with two doses of an mRNA vaccine, HCWs showed minimal neutralization antibody response to the Delta variant and BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron sublineages. After administration of the booster dose, the participants exhibited a stronger neutralizing capacity not only against the Delta variant but also against BA.1 and BA.2. This is consistent with the findings in previous reports regarding BA.1 [2,[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]] and BA.2 [[6], [7], [8]]. However, the median neutralizing antibody titres against BA.1 and BA.2 at 1 and 3 months after administration of the booster dose were significantly reduced compared with those of the previous Delta variant, indicating a reduced effectiveness of booster vaccination against the Omicron variant.

Interestingly, at 1 month after administration of the booster dose, we observed similar neutralizing antibody levels against BA.1 and BA.2, highlighting that the immune response induced by the BNT162b2 vaccine was similar for both variants. This finding of the early weeks after administration of the booster dose is in agreement with those in other reports [6,7]. However, the decline over time seemed to be more pronounced for the neutralizing activity against BA.2. This observation, which needs to be confirmed, could partially explain the surge of BA.2 and the replacement of BA.1, which probably depends on several factors.

As expected, the occurrence of a SARS-CoV-2 infection after administration of the booster dose leads to a strong immune response [9]. The maintenance or even increase in the activity of neutralizing antibodies against the Omicron variant in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection after administration of the booster dose suggests that additional antigen exposure can enhance a memory response. This observation is likely due to expanded B cell repertoire and increased affinity maturation after additional antigen exposure, as previously suggested [16,17].

The main strength of our study is the evaluation of cellular responses along with the humoral response 3 months after administration of the booster dose and the positive effect of an early post–booster dose infection on the persistence of the immune response. The main weakness of our study is that we are not able to compare the effectiveness of BNT162b2 with that of other mRNA vaccines or COVID-19 vaccine combinations.

In conclusion, booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines, as additional antigen exposure, provided a strong response against BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron sublineages. Nevertheless, the response will likely decline over time, and this is one of the factors to consider for the future of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine strategies. The public health implication of these findings is that additional boost might be needed to maintain consistent immune response in individuals who are at risk of severe COVID-19 with the recent emergence of new sublineages (BA.4 and BA.5).

Author contributions

EKA, JD, BCS, ML, and GL conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, performed the data analysis, and wrote and revised the manuscript. EKA, JD, BCS, ML, and GL take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JL, AG, JT, DL, SM, FV, ArD, DHG, JP, DaD, KF, DoD, LB, AlD, AS, DH, MH, FP, BA, and YY participated in the data analysis and revision of the manuscript. ML and GL contributed equally to this work and share similar authorship. All authors gave final approval for the version to be submitted.

Transparency declaration

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This study received the Label of COVID-19 National Research Priority, awarded by the National Steering Committee on Therapeutic Trials and Other COVID-19 Research (CAPNET). This work was supported by the French government through the Programme Investissement d’Avenir (I-SITE ULNE/ANR-16-IDEX-0004 ULNE) managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche and was also supported by a sponsorship from GMF under the aegis of the ANRS-MIE (Agence nationale de recherche sur le sida et les hépatites, Maladies Infectieuses Emergentes).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Véronique Betrancourt, Virginie Dutriez, Anne Guigo, Coralie Lefebvre, Véronique Lekeux, Marie-Thérèse Meleszka, Catherine Mortka, and Anthony Rabat for their technical support and Bertrand Accart for his contribution (Centre de Ressources Biologiques, BRIF number BB 0033-00030). We are also grateful to Séverine Duflos, Marie Broyez, Peggy Bouquet, Clémentine Rolland, Marion Lecorche, Abeer Shaikh Al Arab, Isabelle Tonnerre, Floriane Mirgot, Japhete Elenga Koanga, Laurent Schwarb, Emilie Rambaut, and all the nurses implicated in patient sampling and Mathieu Tronchon for data collection.

Editor: M. Cevik

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.10.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Garcia-Beltran W.F., St Denis K.J., Hoelzemer A., Lam E.C., Nitido A.D., Sheehan M.L., et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. 2022;185:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Planas D., Saunders N., Maes P., Guivel-Benhassine F., Planchais C., Buchrieser J., et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022;602:671–675. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 25 August 2022. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Accessed 31 August 2022. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern.

- 4.Lyngse FP, Kirkeby CT, Denwood M, Christiansen LE, Mølbak K, Møller CH, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron VOC subvariants BA.1 and BA.2: evidence from Danish households. medRxiv [Preprint] Posted 30 January 2022 10.1101/2022.01.28.22270044. [DOI]

- 5.Stegger M, Edslev SM, Sieber RN, Ingham AC, Ng KL, Tang MHE, et al. Occurrence and significance of Omicron BA.1 infection followed by BA.2 reinfection. medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted 22 February 2022 10.1101/2022.02.19.22271112. [DOI]

- 6.Yu J., Collier A.Y., Rowe M., Mardas F., Ventura J.D., Wan H., et al. Neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1579–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2201849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen R.M., Bang L.L., Madsen L.W., Sydenham T.V., Johansen I.S., Jensen T.G., et al. Serum neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 after BNT162b2 booster vaccination. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1274–1275. doi: 10.3201/eid2806.220503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans J.P., Zeng C., Qu P., Faraone J., Zheng Y.M., Carlin C., et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sub-lineages BA.1, BA.1.1, and BA.2. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demaret J., Lefèvre G., Vuotto F., Trauet J., Duhamel A., Labreuche J., et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 patients develop a higher specific T-cell response. Clin Transl Immunol. 2020;9:e1217. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vimercati L., Stefanizzi P., De Maria L., Caputi A., Cavone D., Quarato M., et al. Large-scale IgM and IgG SARS-CoV-2 serological screening among healthcare workers with a low infection prevalence based on nasopharyngeal swab tests in an Italian university hospital: perspectives for public health. Environ Res. 2021;195 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen H, Strengert M, Maaß H, Durand MAY, Kessel B, Harries M, et al. Diminished neutralization responses towards SARS-CoV-2 Omicron VoC after mRNA or vector-based COVID-19 vaccinations medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted 21 December 2021 10.1101/2021.12.21.21267898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Pérez-Then E., Lucas C., Monteiro V.S., Miric M., Brache V., Cochon L., et al. Neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants following heterologous CoronaVac plus BNT162b2 booster vaccination. Nat Med. 2022;28:481–485. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01705-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt F., Muecksch F., Weisblum Y., Da Silva J., Bednarski E., Cho A., et al. Plasma neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:599–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2119641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., Zhao X., Song J., Wu J., Zhu Y., Li M., et al. Homologous or heterologous booster of inactivated vaccine reduces SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant escape from neutralizing antibodies. Emerg Microbe. Infect. 2022;11:477–481. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2030200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia H., Zou J., Kurhade C., Cai H., Yang Q., Cutler M., et al. Neutralization and durability of 2 or 3 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine against Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muecksch F., Weisblum Y., Barnes C.O., Schmidt F., Schaefer-Babajew D., Wang Z., et al. Affinity maturation of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies confers potency, breadth, and resilience to viral escape mutations. Immunity. 2021;54:1853–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muecksch F, Wang Z, Cho A, Gaebler C, Tanfous TB, DaSilva J, et al. Increased potency and breadth of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies after a third mRNA vaccine dose. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Posted 15 February 2022 10.1101/2022.02.14.480394. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.