Abstract

Policy Points.

As a consequence of mass incarceration and related social inequities in the United States, jails annually incarcerate millions of people who have profound and expensive health care needs.

Resources allocated for jail health care are scarce, likely resulting in treatment delays, limited access to care, lower‐quality care, unnecessary use of emergency medical services (EMS) and emergency departments (EDs), and limited services to support continuity of care upon release.

Potential policy solutions include alternative models for jail health care oversight and financing, and providing alternatives to incarceration, particularly for those with mental illness and substance use disorders.

Context

Millions of people are incarcerated in US jails annually. These individuals commonly have ongoing medical needs, and most are released back to their communities within days or weeks. Jails are required to provide health care but have substantial discretion in how they provide care, and a thorough overview of jail health care is lacking. In response, we sought to generate a comprehensive description of jails’ health care structures, resources, and delivery across the entire incarceration experience from jail entry to release.

Methods

We conducted in‐depth interviews with jail personnel in five southeastern states from August 2018 to February 2019. We purposefully targeted recruitment from 34 jails reflecting a diversity of sizes, rurality, and locations, and we interviewed personnel most knowledgeable about health care delivery within each facility. We coded transcripts for salient themes and summarized content by and across participants. Domains included staffing, prebooking clearance, intake screening and care initiation, withdrawal management, history and physicals, sick calls, urgent care, external health care resources, and transitional care at release.

Findings

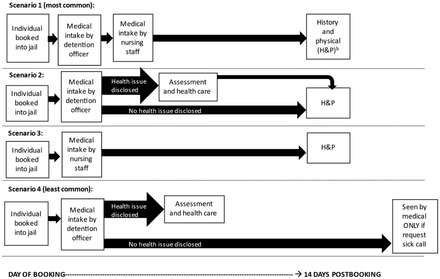

Ninety percent of jails contracted with private companies to provide health care. We identified two broad staffing models and four variations of the medical intake process. Detention officers often had medical duties, and jails routinely used community resources (e.g., emergency departments) to fill gaps in on‐site care. Reentry transitional services were uncommon.

Conclusions

Jails’ strategies for delivering health care were often influenced by a scarcity of on‐site resources, particularly in the smaller facilities. Some strategies (e.g., officers performing medical duties) have not been well documented previously and raise immediate questions about safety and effectiveness, and broader questions about the adequacy of jail funding and impact of contracting with private health care companies. Beyond these findings, our description of jail health care newly provides researchers and policymakers a common foundation from which to understand and study the delivery of jail health care.

Keywords: jails, detention centers, prisoners, inmates, access, health care, health care system, emergency departments

Local jails in the united states incarcerate millions of people each year. In 2019, the nearly 3,000 local jail jurisdictions reported 10.3 million admissions. 1 Unlike prisons, which are operated within the context of state and federal prison systems and generally incarcerate persons with sentences of one year or longer, jails are typically operated by individual county or city law enforcement agencies and predominantly incarcerate individuals awaiting trial or those sentenced to less than one year. 1 , 2 The average length of stay in jail is 26 days, although roughly half are released within 2 days; a small proportion is held for years while awaiting trial. 1

On average, people incarcerated in jail have substantially higher levels of medical need than individuals in the general population. This need, in part, reflects the disproportionate incarceration of Black persons and other persons of color who have less community health care access and worse health outcomes than their White counterparts. 1 , 3 Incarceration is also associated with social conditions such as poverty and homelessness, which are themselves markers of limited health care access and poor health outcomes. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 National surveys have found that jailed persons are 5 times more likely to have a serious mental illness and approximately 12 times more likely to have a substance use disorder than those in the general population. 8 , 9 Those incarcerated in jails also have higher rates of infectious disease, other chronic illnesses, and traumatic brain injury than those in the general population. 10 , 11 , 12 Incarcerated individuals also have lower rates of health literacy than those not incarcerated. 13 , 14

All jails are required to provide health care to individuals in their custody, a right that has been affirmed by the Supreme Court. However, how jails provide care—for example, the specific services provided and the types of health care providers employed—and the amount of funding allocated for health care are typically determined by county officials and jail leadership. 15 Although health care standards and accreditation programs have been developed by both the National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) and the American Correctional Association (ACA), the standards are broad and accreditation is voluntary; existing data suggest that fewer than 20% of jails are accredited by either organization (Amy Panagopoulos, email communication, May 2021). 16

With most jailed individuals returning to their communities within days or weeks, it is well recognized that jail health care can have an impact on the health of both incarcerated persons and the communities to which they return. 17 Yet the relatively short lengths of stay, incarcerated persons’ heavy burden of health problems, and jails’ reliance on local resources and funding pose many challenges to providing health care to jailed persons. In this context, there is a conspicuous absence of research providing a thorough overview of jail health care. Most existing jail health care studies focus on a single jail or are limited to specific elements of care (e.g., screening) or disease entities (e.g., HIV). 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 In response, our objective for this study was to generate a comprehensive description of jails’ health care structures, resources, and delivery across the entire incarceration experience, from jail entry to release. We undertook this effort in the Southeast, which has some of the highest rates of incarceration of any region in the United States and relatively high levels of community need stemming from low rates of state Medicaid expansion and substantial shortages of community health professionals. 24 , 25 , 26

Methods

To develop a comprehensive understanding of health care in local jails, we conducted in‐depth interviews with jail personnel in five southeastern states: Alabama (AL), Georgia (GA), North Carolina (NC), South Carolina (SC), and West Virginia (WV). West Virginia uses a regional jail system (i.e., one jail serves multiple counties), while the remaining states have county‐operated jails. In the following sections we briefly describe sampling, data collection, interview guide development, and analysis. The institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved this study.

Sample and Data Collection

We identified the universe of jails based on those documented in the 2006 and 2013 Bureau of Justice Statistics Census of Jails, and we added and subtracted from this list based on internet searches for jail closings and openings. We categorized jails by size and classified jails’ rurality based on the county in which they are located. 27 We purposefully targeted recruitment of personnel at jails that reflected a diversity of jail sizes, rurality, and geographic locations within our study states. We called top jail administrators and health care staff at targeted jails to identify potential respondents, seeking the person recognized by jail personnel to be most knowledgeable about health care delivery within that facility. As reflected in our results, in a few instances we interviewed (together) two respondents from a single jail, but all results were reported by individual jails.

We conducted interviews with 38 participants in 34 jails from August 2018 to February 2019. The majority of interviews were conducted in person, with 20% conducted by phone. Interviews were typically completed in one to two hours. The interviewers (JCA and ED) had experience conducting qualitative interviews with health care providers and in carceral settings.

Interview Guide Development

We developed the interview guide by conducting a detailed review of the scientific literature, including previous jail‐based surveys, and eliciting input from an expert team of seven people with more than 75 years combined carceral health services research experience. Prior to initiating the interviews, we piloted a draft of the guide with two jails and made revisions based on their feedback. During the study, we iteratively modified the guide to be responsive to emerging themes. The final version of the interview guide is available in the online Appendix.

Data Analysis

We audio‐recorded interviews and had them professionally transcribed; personal identifiers were removed. We used a coding‐based thematic analysis approach and the Framework Method to identify themes within and across the in‐depth interviews. 28 To begin, members of the analytic team (JCA, ED, SBB, CB, MB, PS) independently read the transcripts and produced summaries of each interview, using a template to organize main themes of interest. The team then developed a codebook, with coding categories derived a priori from the study aims and from themes that emerged during transcript review. We piloted the codebook with a subset of initial interviews, iteratively editing the codebook to refine codes and code definitions to facilitate their consistent application. Using Dedoose, two analytic team members independently read and deductively coded each transcript. The team then met to reconcile any discrepancies by consensus. Once coding was complete, we created detailed matrices for relevant codes and summarized content relevant to each code by and across participants.

We have presented findings on the following ten topics, which we determined to be most salient to understanding health care provision within jails: health care staffing, medical clearance and medical intake screening, intake screening to guide initiation of health care, management of drug and alcohol detoxification, history and physical exam, sick call system, urgent care, nonurgent emergency department (ED) use, use of other external medical resources, and transitioning health care at time of release. Across themes, we describe findings common across jails and notable exceptions, along with illustrative quotes. Responses related to staffing, medical intake, and detention officers’ delivery of health care followed broad patterns based on jail size; accordingly, we presented these results stratified by size.

Results

We conducted interviews with 38 participants in 34 jails. Most participants were health care administrators (58%), nurses (21%), or regional health care managers (11%). More than half (58%) had been in their position for less than five years and nearly 20% for more than ten years (Table 1). Our sample included 11% (n = 7) of county jails in AL, 6% (n = 9) in GA, 13% (n = 12) in NC, and 9% (n = 4) in SC, and 18% (n = 2) of regional jails in WV. Most jails were medium‐sized, with a capacity of 100‐999 incarcerated individuals. Roughly 20% were large (1,000+) and 20% were small (0‐99), with jail capacity ranging from 45 to 2,500. Nearly 20% were overcapacity at the time of the interview, and about half were in rural counties. Roughly one‐quarter were voluntarily accredited by the ACA or NCCHC, and another quarter were not accredited but reported that they followed accreditation guidelines (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics

| Participants (n = 38) | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 66 | 25 |

| Male | 8 | 3 |

| Missinga | 26 | 10 |

| Race | ||

| White | 55 | 21 |

| Black | 18 | 7 |

| Missinga | 26 | 10 |

| Age | ||

| <35 | 13 | 5 |

| 35‐55 | 42 | 16 |

| >55 | 16 | 6 |

| Missinga | 29 | 11 |

| Role | ||

| Regional health care manager | 11 | 4 |

| Local nurse/health care administrator | 79 | 30 |

| Jail administrator | 11 | 4 |

| Educational degree | ||

| Registered nurse | 39 | 15 |

| Licensed practical nurse | 37 | 14 |

| Other | 11 | 4 |

| Missinga | 13 | 5 |

| Years in current position | ||

| <1 | 13 | 5 |

| 15 | 45 | 17 |

| 6‐10 | 16 | 6 |

| 10+ | 18 | 7 |

| Missinga | 8 | 3 |

Data not collected at time of interview.

Table 2.

Jail Characteristics

| Jails (n = 34) | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Jail capacity | ||

| Large (999+) | 18 | 6 |

| Medium (100‐998) | 62 | 21 |

| Small (0‐99) | 21 | 7 |

| Overcapacitya | 18 | 6 |

| County rurality | ||

| Urban | 50 | 17 |

| Rural | 44 | 15 |

| Completely rural | 9 | 3 |

| Accreditation | ||

| Yes | 25 | 8 |

| No, follow guidelines | 24 | 8 |

| No or unsure | 27 | 10 |

| Missing | 24 | 8 |

Overcapacity defined as daily population (at time of interview) that exceeds jail capacity.

Health Care Staffing

From the interviews, we characterized the provision of health care in jails, including variations across jail types (Table 3). Among the 34 jails, more than 90% (n = 31) contracted with 12 distinct private companies to provide primary health care services. Among the remaining three jails without private company contracts, health care staff were contracted directly by the county or through the local community health center, and one jail had no health care staff on‐site.

Table 3.

Staffing Models Commonly Seen in Jails

| Health Care Staff | Staffing Model 1: Small‐Medium Jails (Capacity < 250) | Staffing Model 2: Medium‐Large Jails (Capacity ≥ 250) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical providers (MD, PA, NP) | On‐site ≤ 1 day per week | On‐site 3‐7 days per week |

| Nurses (RN, LPN) |

|

|

| Assistants (nursing assistants, medical assistants, medical technicians) | Typically not on‐site | Sometimes on‐site to assist with screening, testing, and medication administration |

| Dentists, dental hygienists, dental assistants | Typically no dentist on‐site or very minimal presence (e.g., once every 2 months) |

|

| Mental health providers (psychiatrists, psychiatric NPs, psychologists, counselors, social workers) |

|

|

| Detention officer support for health care provision |

|

|

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice provider; LPN, licensed practical nurse; MD, medical doctor; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant; RN, registered nurse.

We asked interviewees to describe the types and numbers of health care staff and on‐site health care staffing coverage at their jail. We reviewed data on the types of health care staff most frequently employed by the jails, including medical providers—physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs) like physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs); nurses—licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and registered nurses (RNs); medical and nursing assistants; dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants; and mental health providers—prescribing providers, like psychiatrists and psychiatric NPs, and those providing assessment, counseling, and referrals. We assessed health care staffing availability and on‐site hours in a typical week, then compared this across jails. Although there was considerable variation between jails, we discovered two broad staffing models that generally aligned with size. Of the 33 jails with on‐site health care staff, we categorized 14 as medium‐large (capacity equal to or greater than 250) jails, which had more robust health care staffing, and 19 as small‐medium (capacity under 250) jails, which had fewer on‐site health care staff.

Medical Providers

In medium‐large jails, there was typically greater on‐site presence from medical providers. Medical providers were usually in the jail from three to seven days per week, seeing individuals with chronic care needs, handling medical issues that are beyond the scope of nursing practice, and signing off on charts and medication orders. In contrast, small‐medium jails tended to have less on‐site presence from medical providers, who were present at the jail generally only once a week or once every two weeks. When not on‐site, medical providers were often available by phone to provide guidance to the nursing and jail staff.

Nurses and Assistants

Another key difference between the health care staffing models in small‐medium and medium‐large jails was the nursing coverage. Larger jails tended to have around‐the‐clock RN or LPN presence, and some had medical assistants, nursing assistants, and/or medical technicians who assumed tasks such as drawing blood samples, administering medications, and conducting medical intake screening. In smaller jails, nurses were typically on‐site only weekdays—anywhere from 20 to 40 hours per week—which meant that many of these jails did not have any health care staff on‐site during nights and weekends. Nearly all jails reported having some health care staff—either a provider, nurse, or both—on call to answer questions about individuals’ medical needs when health care staff were not on‐site, and some had staff available to come on‐site after hours, as needed.

Detention Officer Support for Health Care Provision

Regardless of jail size and health care staffing availability, detention officers played a critical role in the provision of health care. It was common for detention officers to transport and accompany individuals to health care appointments (on‐ and off‐site); accompany nurses during “pill pass” (i.e., medication administration); conduct suicide watch; and serve as the “eyes and ears” in the housing units to identify and respond to medical emergencies, including contacting the health care team and providing basic care and first aid.

When health care staff were not on‐site—something more typical in small‐medium jails—it was common for detention officers to assume responsibility for additional tasks related to an individual's health care needs. These responsibilities could include identifying medical emergencies and making the decision to call emergency medical services (EMS); following detox protocols to monitor and care for individuals withdrawing from substances; taking blood pressure and/or blood sugar readings; conducting pill pass; administering insulin injections or observing individuals during self‐administration; triaging requests for health care; and following standing orders to provide basic health care.

Dentists, Dental Hygienists, and Dental Assistants

Medium‐large jails commonly also had a dentist on‐site who attended to individuals one to three days per week, and in some jails, a dental assistant or hygienist accompanied the dentist. In contrast, smaller jails typically had a dentist on‐site less frequently—on a monthly or quarterly basis—or sent individuals to a dentist in the community for care instead of providing on‐site dental care.

Mental Health Providers

Medium‐large jails also had more mental health staffing, usually with a prescribing provider like a psychiatrist or APP with mental health training who saw individuals at least once per week, and also psychologists and social workers who were at the jail daily to provide counseling and, in some cases, referrals for individuals. Some very large jails also employed a separate director or coordinator for mental health services. In small‐medium jails, it was common for on‐site doctors of medicine (MDs) or APPs working as primary care providers to prescribe mental health medications, for individuals to be sent to an off‐site agency for mental health care, and for individuals to receive care solely via telemedicine. In some small‐medium jails, mental health providers were available on‐site to individuals to offer assessment, counseling, or psychiatric services, but this was typically for only a few hours a week or only on an as‐needed basis.

Medical Clearance and Medical Intake Screening

Medical Clearance Prior to Booking

Upon entry into the jail, nurses or detention officers decided whether the arrested individual had any medical needs (typically immediate, severe needs such as major wounds or risk of overdose due to severe intoxication) that would prevent their safe housing in the jail. If such conditions were identified, the arresting officer was required to take the individual to the ED to obtain care and “medical clearance” (i.e., a statement from a health care provider that a person's health status does not preclude incarceration) prior to returning the arrested person to the jail. Respondents reported two purposes for this initial medical screening: first, to provide timely health care, and second, to help ensure that the jails are not financially responsible for serious injuries or medical complications resulting from an incident that occurred prior to incarceration. While this initial medical screening occurred universally for all individuals entering the jails that were interviewed, the frequency with which medical clearance was required varied by jail, and it typically corresponded with the jail's availability of on‐site health care resources, such as staff, to handle needed medical concerns.

Medical Intake Screening: Information Collected

Shortly after being booked into the jail—and sometimes during the booking process—individuals were typically screened about their health and medical history. This process was commonly referred to as “medical intake,” “medical screening,” or “intake screening.” Although screeners varied by jail and health care company, they often queried about current or past medical conditions and treatment, recent surgeries or hospitalizations, exposure to or diagnosis of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, hepatitis), prescribed medications, allergies, illicit substance use, health issues that may affect mobility or diet, dental problems, pregnancy, and history of abuse or victimization. Individuals were also typically screened for tuberculosis (TB), mental illness, and suicidality, with questions assessing the presence of symptoms or risk (e.g., currently experiencing persistent cough or night sweats). Finally, the detention officer or health care staff conducting the screening typically observed the individual and noted the presence of recent injuries, signs of physical distress, or abnormal behaviors (e.g., confusion, grandiosity). Some also noted factors they perceived to be predictive of victimization during incarceration (e.g., small stature, cognitively impaired).

The two clinical screening tests most frequently administered during the intake process were the tuberculin skin test and a pregnancy test. While some jails performed TB tests on all individuals, most jails first asked a series of questions about TB risk during the intake screening, then administered a tuberculin skin test only to individuals deemed to be high‐risk. Similarly, some jails tested all females for pregnancy, but most administered pregnancy tests only for females who either disclosed that they were likely to be pregnant or who used illicit substances.

An individual's vital signs were often taken during medical intake, and some jails conducted full physical exams at this time. Individuals were commonly asked to sign release forms granting the jail permission to obtain their medical records from other health care providers or pharmacies and were provided with information about how to access care and file a health care grievance while incarcerated.

Medical Intake Screening: Four Variations on the Process

We identified four variations of the medical intake process (Figure 1). In nearly three‐quarters of the jails interviewed, detention officers conducted the medical intake screening during booking (scenarios 1, 2, and 4 in Figure 1). If they found an immediate health concern during this screening and the jail had on‐site health care staff, the health care staff were notified and initiated care. If no immediate health needs were disclosed to officers, information collected during the intake screening was often still shared with health care staff and was used to triage or inform care provision. Some jails always—regardless of whether a health need was found—followed the intake screening conducted by the detention officer with another screening conducted by a member of the health care team, and this was usually done within a couple of days and typically by a nurse (scenario 1). As one participant explained:

Figure 1.

Four Variations of Medical Intake and Assessment Process in Jailsa

aPresented in order of most common to least common. For unlabeled arrows, scenario moves forward regardless of health issue disclosure.

bAssessment and health care and H&P are conducted by health care staff (i.e., nurses or medical providers).

They do one at booking, the officers do, and then I do one within 24 hours. I see them within 24 hours. . . . There is no difference in what the officer asks and what I ask. . . . Mine's just more in‐depth, more medically in‐depth. . . . It has to be within 24 hours unless it falls on the weekend. Then we get them that Monday when we come in. (Jail 32, Medium)

In a little less than half of jails interviewed, only individuals that disclosed a health problem to a detention officer during the intake screening received a follow‐up screening or evaluation by health care personnel (scenario 2). In these jails, those who did not disclose a health problem to the detention officer were typically seen 10‐14 days after booking for what is commonly known as a “history and physical,” or “H&P.” As one participant described, the result is that many individuals never see a health care staff member before they are released from jail: “You don't have to see them right when they come in, unless they have medical problems. . . . They're in and out so much, usually they're gone within the 10 days. . . . We often don't see ’em, but if they're still here, then that's when we do the H&P” (Jail 10, Medium).

In one jail, individuals who did not disclose a health problem to a detention officer at booking were seen by health care staff only if they submitted a request for medical attention (i.e., sick call request, discussed in detail later in the paper) (scenario 4). While having detention officers conduct the intake screening appeared to be common practice and was often necessary in the many jails lacking around‐the‐clock nursing coverage, some participants expressed concerns that if it was not followed by a second screening by nursing staff, officers could miss important health issues such as withdrawal, overdose, or the potential for self‐injury. Further, these outcomes could occur within minutes or hours after entering the jail. As one participant described:

The officers actually ask the inmates as they come in some health questions. If they answer no to everything, then they don't necessarily see the nurse. I have an issue with that. I think everybody should be seen by the nurse. . . . The problem we have is there's so many people come through the door here, like hundreds a day. The nurse can't possibly see hundreds of people a day. Plus, a lot of them come in and, basically, are turned around. . . . It's just volume, really, is the problem. They're either trying to screen out the people who are absolutely fine and anybody who's not fine. I don't like it. . . . Even if they're sittin’ in the holding cell for six hours, they can still be suicidal. A lot of people come in here off the street, and they have significant mental health issues anyway because they don't have any care. They're still sittin’ in a cell for six hours before they're bailed out or before whatever happens to them, happens to them, and they get put back out. (Jail 5, Large)

In roughly a quarter of jails interviewed, detention officers did not conduct the intake screening and it was instead conducted by a nurse, nursing assistant, or medical assistant, typically anywhere from a few hours to 24 hours after booking (scenario 3). Most of the jails that had only health care staff conducting the intake screening were medium‐large, and most had 24‐hour‐a‐day nursing coverage. One participant described the rationale and typical process in the following way:

They [detention officers] don't do any kind of health screening because they're not medical, and I just don't think they need to be involved in it. What they do is they book’em in. Then a sheet is produced that has their picture on it, what their charges are, which we don't care. We pick up that sheet, go out and get’ em, and bring’ em into our office, where we do the health assessment. . . . Absolutely. It's an RN. (Jail 22, Large)

Intake Screening to Guide Initiation of Health Care

The information collected by detention officers and health care staff during the intake screening process served several functions, typically guiding decisions about housing and diet and determining whether additional testing was needed, how soon the individual needed to be seen by a nurse or medical provider, and if and when medications were initiated. For example, as described by the following participant, a pregnant person would typically be placed on a high‐calorie diet, someone with a seizure disorder would be assigned a bottom bunk, and a person with diabetes would have their blood glucose level checked:

We're making referrals out to mental health if they have mental health history. If they're suicidal, then we're puttin’ ’em on suicide watch and different things like that. If they're high blood pressure, then we're checkin’ their blood pressure regularly and referring ’em, again, to the doctor. If they're seizure, we're put ’em on the bottom bunk. It's just a whole lot of little steps you have to take based on what you find in intake. (Jail 11, Medium)

If someone had a health condition that required medication, jails typically tried to obtain medical records that documented a current prescription, provided the medications or similar medications as soon as possible, and scheduled an appointment with a medical provider, if needed. Some jails permitted individuals or their family members to bring medications from home for use during incarceration. As one participant described, if the person did not have a current prescription but reported having a health care condition that needed immediate attention, they typically saw the nurse or medical provider for an evaluation, and then medications were administered, if deemed necessary:

It depends on the medication itself. But yes, any medication that they say they're on, even if they don't—but sometimes they'll even bring some in, but if they say they're on medication, we try to get the pharmacy that they're going through and then verify it through the pharmacy. . . . If for some reason we can't verify it, or if it's outdated or expired or whatever, then they're—we give them the assessment. Especially—we want to make sure that they have their diabetic medication, their chronic medication. . . . We want to make sure that if you're on metformin or Coumadin or something like that, that it doesn't lapse. So, we—even if we don't get a verification on that, we have the nurse practitioner assess them and then write an order for that type medication. (Jail 3, Medium)

In addition to receiving medication, individuals with chronic health care conditions like diabetes or hypertension were commonly placed on a care plan that included periodic lab work, frequent monitoring of blood glucose or blood pressure, an initial visit with a doctor or APP within 30 days of booking (though often sooner), and follow‐up visits every three to six months, unless more frequent care was needed. An example of one jail's system and the types of health conditions that required chronic care management were described by one participant in the following way:

If they report any diabetes, seizures, asthma, ulcers, any heart conditions, HIV, any thyroid, renal problems, any hepatitis . . . then it automatically triggers a task for the nurse practitioner. That's within the first 30 days that they are here. They will see her for what we call our chronic care clinic to see what type of plan of care that we need to do for them. (Jail 27, Medium)

Information collected during the intake screening also prompted referrals to mental health providers, if available at the jail or through an agency in the community. Mental health providers would sometimes do a follow‐up assessment to determine the extent of the condition and, depending on available resources, schedule the individual to receive one‐on‐one or group counseling or to speak with a prescribing medical or mental health provider about mental health medications. In jails that did not have mental health providers on‐site, it was common for the medical provider to prescribe mental health medications. In some cases, those who were taking medications prior to incarceration were able to continue taking the same medications. In other cases, individuals were prescribed a different medication from what they were taking previously, as many jails use a formulary or restrict the use of certain medications.

An individual's responses to the suicide‐screening questions, along with the officer or health care staff's observation of the person, determined their level of risk and could lead to placement on suicide watch. This usually entailed housing the individual in a highly visible cell (e.g., in the booking area in the officers’ line of sight or in a cell with a camera), limiting access to anything the individual could use to harm themselves (including clothing, blankets, and utensils), restricting free movement, and having routine checks performed by detention officers and health care staff. One participant described the typical process in the following way:

They are stripped down. They have nothing in their cell but a bare mat. They get a—what they call the turtle suit, which is a gown, Velcro gown that's made out of a quilted material. I say horse blanket material ’cause that's exactly what it's made out of. They get a blanket made out of the same stuff so that they can't shred it or tear it and use it to hang their self or anything. They're not allowed any kind of utensils. They have to eat with their hands. They get 15‐minute cell checks. Every 15 minutes, they're checked by the officers. I check them twice a day. (Jail 32, Medium)

In some jails after the intake screening, jail officials may also facilitate the early release or transfer of an individual with a health care condition that is expensive or resource‐intensive, such as a high‐risk pregnancy or dialysis, or a condition requiring an extended hospital stay or expensive medication, like HIV. There are a number of ways that jails might expedite the release or facilitate the transfer of individuals to another jail or prison, including allowing special privileges like extra phone time to facilitate bail payment, or working with the courts to unsecure the bond, release on supervision, expedite the trial, or release the individual to the ED via involuntary commitment. In one state in our sample (NC), jails also had the option of sending individuals with high medical needs to the state prisons for more comprehensive care via a mechanism referred to as “safekeeping.” The following participant described some common reasons for releasing individuals early:

If I get a patient in, a hospice patient or something like that that's on the MS Contin and takes the oxycodone for breakthrough and that sort of stuff, I gotta get that person out of here, ’cause we're not gonna be able to give them those medicines. . . . I go to the jail admin and try and get them out of custody. . . . Yeah, if they're on that kind of medication and they're on hospice care, then they're sicker than we wanna deal with. We try and get rid of dialysis patients as quickly as we can too, because they don't wanna have to transport them three days a week to dialysis. (Jail 29, Medium)

Management of Drug and Alcohol Detoxification

If an individual disclosed recent drug or alcohol use or appeared to be intoxicated during intake screening, this typically prompted further observation and placement on “detox protocols.” Many jails housed those detoxing in cells that facilitated frequent monitoring, such as holding cells or a medical isolation or detox unit. Standardized tools like the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) and Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) were commonly used to assess and manage detoxification from alcohol or drugs. With these tools, nurses—and sometimes detention officers—assessed the individuals at regular intervals, observing their behavior and asking questions to detect and respond to concerning symptoms such as tremors, sweating, and tactile, auditory, or visual disturbances. The following participant described one example in which both health care staff and detention officers were involved in this monitoring:

That is me [who keeps an eye on detoxing individuals]. I have to see them. I think it's three times a day, I do. I usually do it morning, noon, and right before I leave. Officers do keep the watch on them too, and they will give medications if they need to as far as the protocol goes. (Jail 32, Medium)

Guided by internal policies and information gathered from these assessments, jails made decisions about the level of care that individuals received. As described by the following participant, approaches to withdrawal treatment ranged from hydration with ice water or Gatorade drinks to provision of medications that eased symptoms and prevented potentially life‐threatening complications:

The alcohol and benzos get the Librium, and the opiates get their Tylenol and their meclizine and their antinausea and stuff like that. They all get Gatorade, as much Gatorade as we can give them. We give Gatorade because that's [laughter] like the cure‐all, apparently. (Jail 5, Large)

Jails typically took a different approach toward pregnant persons at risk of withdrawing from drugs or alcohol, particularly those with opioid addiction, as preventing harm to the pregnancy requires an additional level of care that many jails were unable to provide. Most were unable to provide care for these women on‐site, and either facilitated early release from the jail or arranged for medication‐assisted treatment (MAT) by sending them to a local methadone clinic or, in one study state mentioned earlier, by transferring them to a prison for MAT via “safekeeping.” As one participant said, “Before we initiate the COWS protocol, any female that needs it, they have to have a pregnancy test because if they're addicted to heroin, and they're pregnant, then we have to set them up to go outside to the methadone clinic for methadone dosing” (Jail 2, Large).

History and Physical Exam

Nearly all jails interviewed conducted a routine physical examination on every individual within the first month of incarceration. As noted, this was often referred to as a “history and physical,” “H&P,” or “health assessment,” and it usually occurred 10 to 14 days after booking. While the H&P can be similar to the intake screening, in most facilities it was conducted by a nurse, involved a physical evaluation and assessment of vital signs, and gave the individuals an opportunity to disclose additional information about medical history or health needs that they may not have disclosed during the intake process. One participant described the purpose of the H&P in the following way:

The thought process is the inmates come in, they're tired, they're coming off of a high, or whatever. They've been fighting their spouse or girlfriend, boyfriend. They've been running from the dog. Sometimes they'll give you some information, but they may not give you all the information. What the 14‐day physical does is give them the opportunity to go upstairs, rest, then they'll come back down to the 14‐day physical and be like, “Oh, yeah. I didn't tell you that I had”—[laughter] It's just another opportunity to try to identify any problem that the patient has. (Jail 11, Medium)

Sick Call System

Outside of the H&P and chronic care management system, to obtain nonurgent health care, individuals were required to place a sick call request. They either completed a paper form and handed this to a detention officer or to health care staff, placed the paper form in a drop box to be collected by health care staff, or, as described by the following participant, entered information into an electronic kiosk: “Well, everything's computerized, so they go to the kiosk, just like you would go to rent your Redbox movies, and they put in a medical request . . . and it comes to me” (Jail 4, Medium).

Most jails charged a copay for sick calls, which ranged from $3 to $20. Jails did not typically deny health care if the individual was unable to pay the fee, but, as described by one participant, they often deducted the amount from the individual's jail savings account: “They get charged $5. . . . [If they can't pay] it still goes on their account and it doesn't leave their account. When they come back, it's still there. If somebody puts money on their books, the first thing that's satisfied is their medical charges” (Jail 6, Large). Typically, care related to a chronic condition (e.g., diabetes or HIV) and mental health care did not incur copays. Similarly, while many jails charged individuals for medications, there was typically not a fee if the medication was prescribed for a chronic condition or mental illness.

In some jails, particularly those with more health care staff available, sick call requests were reviewed periodically throughout the day, but in other jails, health care staff reviewed them one or two times each day, often first thing in the morning. One participant described this in the following way:

It's a computer kiosk in each one of the dorms. When they put that in, it comes directly to my [nurse's] computer. I check that every morning. I always tell ’em when I do their medical assessment, “Look, I check emails—I check sick calls once a day. That's at 8:30 in the morning. I don't have time to be runnin’ back and forth. It doesn't have a little bell that dings and tells me I got a new one.” If it's not in there before then, I will not see it ’til the next day. I always tell ’em if it's an emergency, by all means, let the staff know immediately. If it's on a Friday, I won't see it ’til Monday. It won't do you any good to put in three more over the weekend—which I've had people do. (Jail 7, Small)

Once nurses reviewed the requests, they triaged them, prioritizing those with time‐sensitive health care needs. In most jails, those who placed sick call requests were typically seen by a nurse within 24‐48 hours. As described by the following participant, in jails without health care staff on‐site during evenings and weekends, an individual with a nonurgent health care need was typically not seen until the next business day: “The ultimate goal is within 24 hours. Doesn't work like that on the weekends. If they send me anything after Friday at 4:30, it's gonna—generally speakin’, gonna be Monday before they get seen” (Jail 34, Medium).

Urgent Care

Detention officers stationed in the housing pods typically observed or received a verbal request when someone needed urgent health care. As described by one participant, detention officers then notified health care staff of the situation and sometimes began providing first aid or CPR while waiting for health care personnel to arrive: “They also assist in‐house. Say if there's an emergency that goes on, all of the staff are CPR and first‐aid certified. They respond to an emergency. They provide whatever care's needed, as far as—just like basic first aid or CPR if needed until medical gets there. Then medical takes over” (Jail 18, Medium). If health care staff were not on‐site, detention officers either contacted the on‐call medical provider or nurse for guidance or, if the situation was very urgent, called 911.

When urgent health care needs exceeded what the jail was able to manage, jails typically sent individuals to the ED. The most commonly cited reasons for sending an individual to the ED included injuries like broken bones or lacerations, chest pains or other indication of potential cardiac issues, loss of consciousness, and severe withdrawal from drugs or alcohol. Other frequently cited reasons included psychotic episodes or severe suicidality, seizures, suspected drug overdose, unmanageable blood sugar in diabetics, and childbirth. As described by one participant, depending on the level of urgency, jails used EMS or county vehicles like deputy or patrol cars to transport individuals to the ED:

If he's not responding, then y'all gonna—they automatically know, hey, we have to call the ambulance. If he just has, say, for instance, sprained his ankle, a lot of the times, what we can do is, they will call and get—or they'll be like, “Hey. Can you get a deputy to come through and pick him up and transport him to the hospital?” (Jail 28, Small)

Some jails called EMS to assess individuals, and others relied on EMS solely for the purpose of transporting them to emergency medical care. Some of the differences in the ways that jails were using EMS appeared to be related to the jail's financial arrangement with EMS. In some counties, a jail was billed if EMS transported the individual, but was not billed if EMS only conducted an on‐site assessment without transporting the individual. In other counties, EMS billed the jail for both assessments and transports to the ED, while in other counties, the jail was not billed at all by EMS. One participant described the jail's rationale for trying to avoid EMS transport:

Then the doctor would tell them, “Okay. Well, have EMS check him out first before you transport”—’cause our priority is we wanna provide good care, but we also want to save the county from havin’ to pay an unnecessary ER bill, and especially some of ’em—if they're cardiac, that can be a big bill. (Jail 7, Small)

Nonurgent Emergency Department Use

Some jails relied on EDs to provide nonurgent care for individuals, especially jails that lacked the on‐site resources—staffing, equipment, or appropriate space—to manage the health issue. For example, while some jails had X‐ray, ultrasound, or EKG machines on‐site, others relied on the ED for this type of diagnostic equipment, or contracted with a company to provide the service on‐site during business hours, but relied on the ED for after‐hours diagnostics. One participant described this in the following way: “Normally, most things, we can treat in‐house here ’cause we're so small—but there are times like folks that got in a fight, and maybe it was on a weekend, so they've had to go to the emergency room because—to get an X‐ray or something” (Jail 33, Small).

Alternately, jails may have had the necessary equipment, like an X‐ray machine, but did not have medical providers on‐site to operate the equipment or interpret the results at the time that this was needed. Similarly, jails of all sizes frequently sent individuals to the ED for simple laceration repairs when medical providers were not on‐site. This is described by the following participant, who works in one of the largest jails in our sample: “We don't have a provider here today, so if there were injuries that needed like sutures or something like that, we'd have to send them out” (Jail 2, Large).

In some jails, the ED was used when the facility did not have the appropriate space to house sick individuals. For example, as described by the following participant, an individual who is positive for TB in a jail without a negative pressure room would be sent to the ED:

If the PPD is positive [for TB], then we get a chest X‐ray. Then if the chest X‐ray is positive, and then they got symptoms, and then of course they go. We [do] send ’em to the ER, ’cause we don't have a negative pressure room, so they have to go out. (Jail 13, Large)

The extent to which jails used EDs varied widely and depended both on the availability of on‐site resources (as described earlier) and on the jail or decision maker's aversion to risk. While some jails erred on the side of caution and made decisions that would both protect the individual from serious injury or illness and protect the jail from liability, others had more tolerance for risk and were more hesitant about sending individuals to the ED. Such hesitancy was often related to the high cost of sending individuals to the ED and, as referenced by the following participant, to experiences with individuals being untruthful about medical conditions in order to have time outside of the jail:

Only if I have to. It's just simply for that because a lotta times, you send ’em over there [to the ED], and they don't need—they don't really need to go. We try not to send—if they need to go, we're gonna send ’em, but you know these people that say they're havin’ chest pain, and they're—if we sent everybody out who said they had chest pain, we'd be . . . (Jail 17, Medium)

To avoid expensive ED bills, jails used a variety of strategies on‐site to assess and triage individuals with health concerns. These strategies relied on staffing and diagnostic resources, a number of which were more common in larger jails, such as around‐the‐clock on‐site presence of RNs and after‐hours on‐call presence of providers to assess and triage, as well as on‐site X‐rays and EKGs. Jails also provided training for health care staff to recognize the signs and symptoms of cardiac arrest (often to discern between falsified claims and true medical emergencies), trained officers as first responders, and established protocols to guide whether to send someone to the ED or not. One participant described a couple of the strategies used by her jail:

If somebody complains of chest pain, okay, “What kind of chest pain is it? Does it hurt if you take a deep breath? Yes. Then it's not your heart. You're not having a heart attack.”. . . Previously, they would have gone to the emergency room because they complained of chest pain. . . . We can do an EKG here. . . . That's real easy. The computer, the program on the EKG machine will tell us whether it's normal or abnormal. . . . I've been doing this long enough, I know if somebody's having a heart attack. (Jail 15, Small)

Use of Other External Medical Resources

In addition to EDs, jails utilized a number of other external resources—most commonly, mobile diagnostic companies, health departments, hospitals, and specialty clinics—to provide health care to individuals. In some cases, medical providers from the external company or clinic came on‐site to provide a service, but jails often transported individuals off‐site for care.

As noted previously, if individuals needed an X‐ray, most jails had access to a company that came on‐site to provide this service, and many used the same company to provide ultrasounds. Jails that did not work with a company like this typically sent individuals to the hospital, urgent care center, or a local doctor's office for diagnostic assessments.

Most jails relied on relationships with local health departments (LHDs) to facilitate provision of health care services. Services provided by LHDs most commonly included prenatal care and testing and/or treatment for communicable diseases like HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and hepatitis C. Some also provided assistance with applications for the HIV Medication Assistance Program (HMAP), contact tracing for communicable diseases, health education, TB treatment, and hepatitis A vaccinations.

Jails also sent individuals off‐site for specialty care, though use of specialists tended to happen more frequently in larger jails with more resources. As noted, some jails expedited the release or transfer of inmates to avoid providing high‐cost or resource‐intensive health care, and this was often for conditions requiring specialty care. In jails that did send individuals off‐site for specialty care, the most frequently accessed specialists were obstetricians and orthopedists, for pregnant or injured individuals. Other specialty care utilized by jails included dental, infectious disease, cardiology, ophthalmology, wound care, dermatology, urology, nephrology/dialysis, oncology, hematology, immunology, podiatry, psychiatry, addiction support services, and physical therapy. As one participant noted, jails are not equipped to provide specialty care:

Anything that's specialized that—we're not specialists in anything particularly. We're jack‐of‐all‐trades, but we send them out to the people who can do the care. If the nurse practitioner or the doctor feels that they really need to be assessed by a surgeon or whoever out in the community, then we refer them out. (Jail 5, Large)

Transitioning Health Care at Time of Release

Some jails took steps to support released persons’ continuity of health care and access to community social services upon their release. Several jails identified significant challenges to supporting transitional care. Most commonly, these included a lack of information about the timing of release (impeding the provision of the postrelease medications or other resources), insufficient staffing to support the transition (e.g., social workers to assist with applications for Medicaid), and inadequate community safety‐net resources and affordable health care.

When jails did support transitional care, they most commonly provided released persons a small supply of their prescribed medication and a resource list that contained contact information for health and social service providers, though some jails released individuals without these resources and others provided additional support.

In most jails, if an individual brought a medication into the jail, they were permitted to take the remainder home. It was also common for jails to release individuals with a supply of medications, and this was typically a 7‐day supply, though it ranged from a 2‐ to a 30‐day supply. Although some jails had a policy of sending individuals home with a standard supply of medications, a number of them reported giving releasees more medication—typically, the remainder of what had been ordered for them—since they had already been paid for and the jail was unable to use the medication for other inmates.

Some jails had additional policies to facilitate medication adherence after release. For example, in addition to sending the individual home with a supply of medication, some jails called the prescription into a local pharmacy so that it was available once the initial supply was finished. Some jails also gave a greater supply of medication to those with mental illness or those who had been incarcerated for longer periods, based on the assumption (described by the following participant) that it might take these individuals longer to make an appointment with a medical provider:

We have some long‐term inmates that have been here for a year or more. At that point, they're not gonna have that rapport with their doctor, so it's gonna take ’em a while to get to see somebody. If they've been here that long, I try and send as much medication as I can home with them, just to get over that initial three weeks or so until she can see the doctor, kind of a thing. (Jail 15, Small)

Alternately, some jails had policies that could impede continuity of medications, with a few reporting that they never provided medications at release. Others only sometimes provided medications at release, and this was typically for certain health care conditions (e.g., some chronic conditions) or for indigent persons. Additionally, rather than providing medications at release, some jails provided only a prescription to the local pharmacy, creating uncertainty as to whether the released person would be able to quickly retrieve and pay for their medication.

Jails reported several ways that they supported released persons’ access to community health care providers. Most commonly, jails simply released individuals with a list of community resources. Some jails also informed released persons of upcoming medical appointments, provided health care referrals to community providers, or strongly encouraged released persons to seek care for a specific medical condition. A few jails went further by contracting with providers who cared for individuals both during incarceration and after release (typically for mental illness or substance abuse), further helping to ensure care continuity.

Beyond health care, some jails collaborated with a community agency to initiate enrollment applications for postrelease benefits such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (commonly called WIC) or Medicaid for pregnant persons, the HMAP for people living with HIV, or Veterans Affairs benefits. A couple of jails had transitional care coordinators to help prepare individuals for release, including assistance with accessing benefits.

Some jails also arranged for released persons to access necessities (such as food and shelter) or coordinated with local agencies that provided these services. Other jails and their partners provided assistance applying for community substance use programs. One jail gave those with a history of opioid use a supply of Narcan and instructions on use to prevent overdose.

Discussion

In the United States, jails have become a major de facto provider in the US health care safety net for many of society's most vulnerable, infirm, and impoverished. Although jails are responsible for providing health care to millions of people each year, existing jail health care studies are limited in their scope. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 To our knowledge, the current study provides the only description to date of all major jail health care processes from entry to release.

We identified wide variability in health care staffing and resources, but overall, the provision of jail health care reflected a scarcity of resources; in response, jails relied on a patchwork of strategies to mitigate that scarcity. Further, some of these strategies, such as the use of detention officers to provide health care, can have a substantial impact on health, and yet have remained largely unacknowledged in the public health/biomedical literature.

Foremost, we identified marked differences in health care staffing between smaller and larger jails. Compared to larger jails, which typically reported a continual presence of on‐site nursing staff, nursing at jails with under 250 incarcerated persons was often limited to a few hours of coverage on weekdays only. When nurses are not on‐site, individuals either reportedly wait until the next business day to receive medical attention or receive screening and triage from detention officers, who then rely on on‐call medical providers, EMS, and EDs for care. Both scenarios—waiting until the next business day and relying on on‐call or outside providers—likely result in treatment delays and, more generally, limit access to care.

Our findings also highlight the insufficient availability of behavioral health staffing. Behavioral health needs outpaced capacity in even the most well‐staffed jails. Among smaller jails, we found that the best staffing scenario was the availability of a single mental health clinician—a situation that respondents found grossly insufficient. In fact, it was most common in small jails for mental health services to be provided by off‐site agencies, which were often used only when an individual was in crisis.

Further, we found that detention officers were responsible for a host of health care‐related duties. Detention officers’ lack of health care training, along with the position of power they hold over those in custody, may limit their ability to ascertain sensitive or vital medical information and to respond accordingly. These challenges may be most prevalent at jail entry, when officers are commonly responsible for the intake screening. If a detention officer misses a time‐sensitive health care issue at the intake screening, the person in custody could languish for days or longer without medical intervention. Among other conditions, such lapses may be most relevant for alcohol and drug withdrawals and overdoses; half of jail deaths related to withdrawal or overdose occur within the first day of incarceration. 29

Medical intake screening was just one of many ways that detention officers reportedly performed health care duties without professional training. Although not universal among respondents, other commonly reported health care responsibilities included monitoring individuals withdrawing from alcohol and other substances, administering prescription medications, observing individuals self‐administering insulin, and triaging requests for health care. Saddling detention officers with health care responsibilities poses risks to the health and safety of incarcerated individuals and is a liability for jails and detention staff.

Another key finding in our research was the extensive use of EMS and EDs by jails for nonemergent assessment and care provision. While jails are using these resources for their intended purpose—medical emergencies—they are also using EMS and EDs when they lack on‐site resources needed to provide basic assessment and care.

The scarcity of resources for health care provision in jails has the potential to result in treatment delays, limited access to care, lower‐quality care, unnecessary use of EMS and EDs, and limited services to support continuity of care upon release. Just as jails disproportionately incarcerate people who are Black and economically impoverished, these populations are disproportionately impacted by the health services available—or absent—during periods of incarceration. Currently, a variety of stakeholders—prosecutors, county commissioners, jail administrators, the private health care companies with whom jails frequently contract, among others—can influence decisions about who is incarcerated in jail, how jail health care resources are allocated, and the availability of and access to social services. Their collective decisions are most often described as the sum of a political, economic, and logistical calculus—with, perhaps, a growing acknowledgment of public health considerations, spurred by the opioid crisis and the COVID‐19 pandemic. Yet the implications for and undercurrents of race and class in these decisions cannot be ignored. Indeed, for many of those who are incarcerated, insufficient access to health care in jail is just one of numerous structural barriers to health, longevity, and prosperity that they encounter routinely. Further, the COVID‐19 pandemic serves as a stark reminder that the allocation of resources during incarceration can affect not only the health of jailed persons but also that of the often‐vulnerable communities to which they return.

Policy options vary widely in regard to political will, expense, needed resources, and effectiveness. These options include piecemeal approaches to increasing jails’ ability to provide health care, such as providing health care training to detention officers (e.g., cross‐training as emergency medical technicians—EMTs), or improving partnerships between jails and community agencies to provide health care and behavioral health care to incarcerated persons. 15 Other strategies require substantially more investment and stakeholder buy‐in, such as increasing allocation of financial resources for jail health care, shifting oversight from local jail and community leaders to state or federal agencies, and establishing mandatory national standards for jail health care provision and staffing. Additional funding would enable jails to hire—directly or through contracts—sufficient medical or behavioral health staff. As suggested by the World Health Organization and others, moving from voluntary to mandatory standards with state or federal oversight would ensure that care meets minimum requirements for content and quality. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34

One possible mechanism for increasing funding, shifting oversight, and implementing national standards is to fully expand Medicaid and remove the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP), at minimum for pretrial detainees. 35 Medicaid expansion has been demonstrated to improve access to care, quality of care, and health outcomes, and many of those incarcerated in jails would be eligible under current income guidelines; yet, 12 states, most of which are in the Southeast, have elected not to expand Medicaid. 4 , 26 , 36 , 37 The MIEP bars the use of Medicaid funds for incarcerated persons. Removal of this policy for pretrial detainees—which comprise approximately two‐thirds of all jail detainees—has been endorsed by a joint task force of the National Association of Counties (NACo) and the National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA) and could improve jails’ willingness and ability to provide needed care. 1 , 38 Additionally, shifting oversight to the Medicaid program could establish the expectation that jails follow the health care guidelines prescribed by the program. 30

Another possible mechanism is restructuring the jail system in a way that mirrors the public school system, with oversight and funding from local, state, and federal levels. National standards could be developed and incorporated into this system, with financial incentives for meeting or exceeding standards and repercussions for failing to do so. Given the wide diversity of jail populations and resources, a one‐size‐fits‐all approach may not be feasible, but standards could be tiered based on jail size and possibly other factors, such as typical length of incarceration. 39

Incarcerated individuals also need legal recourse against inadequate treatment in jail. Historically, litigation has been a powerful tool for the reform of health conditions in jails. 40 , 41 However, the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA), which was passed in 1996, creates barriers to filing and winning federal civil rights lawsuits. As such, repeal of the PLRA is another important step toward ensuring that jails provide adequate health care. 42

Regardless of financial and oversight models, the high proportion of jailed persons with substance use and other behavioral health disorders suggests that hiring enough psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors would require a substantial investment. Although jails do need additional mental health staff, jail environments can be particularly counterproductive for treating those with behavioral health disorders. 43 In response, advocacy groups such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness recommend reducing the number of individuals with behavioral health disorders who are arrested and incarcerated in jails. 44 To achieve this reduction, communities must support robust treatment options, social services, and diversion policies. Jails should also utilize the guidance for treatment, service, and policy decisions that is increasingly available through the National Institute on Drug Abuse Justice Community Opioid Intervention Network initiative, which funds research to identify best practices to address drug use among justice‐involved populations. 45

Similarly, the high incarceration rates in the United States compared to other countries suggest that incarceration could be used much more sparingly without endangering public safety. This possibility was largely substantiated with the 2020 reductions in jail populations in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. 46 Reducing jail populations is possible through strategies such as ending the use of money bail and eliminating many of the legal system fines and fees, which disproportionately punish those who have few financial resources. Using alternatives to arrest and prosecution for minor charges and investing in community resources are other ways to decrease jail populations. 47 , 48

There are a number of potential ways to strengthen the health of incarcerated individuals and the communities to which they return. Some approaches require investment and change at the level of an individual jail, while others require changes at a county, state, or even national level. Our research highlights how little is known about the delivery of jail health care and the need for more systematic evaluations. To understand the most effective approaches, there is a need for greater data collection and evaluation of jail health services. Future research should also incorporate the perspectives of state and federal regulators and policymakers, private health care contractors, and local health department staff, as their input is critical to understanding the myriad factors that shape or have the potential to influence jail health care. With buy‐in from jails and other stakeholders, the diversity of practices across US jails and their surrounding communities could present an opportunity for identifying best practices regarding, among others, staffing models, screening, triaging for emergency care, and release.

This study has a few limitations. First, we focused on a single region of the country and our participant jails were not randomly selected. Nevertheless, we purposefully included jails that were likely to reflect a broad set of experiences and practices. In retrospect, jails that lack health care staffing are likely underrepresented in our sample. This issue will likely be resolved in the future as we are currently using findings from this study to develop and deploy a survey that aims to be representative of jails in our target population of southern states. Second, given the dearth of existing knowledge about jail health care delivery, we were unable to address the entirety of health care delivery issues. For example, our interviews focused mostly on implementation of services and less on the development of policy and health care financing, particularly in the context of widespread jail health care contracting with private companies. Finally, our findings do not reflect the perspectives of incarcerated individuals. Their perspective is critical to developing patient‐centered recommendations for jail health care delivery.

Conclusion

This research sheds light on the scarcity of resources available for health care provision in jails and on the challenges this poses to the provision of high‐quality, timely, equitable care for incarcerated persons. However, much remains unknown about the effectiveness of current strategies for jail health care provision, the adequacy of jail funding, the impact of contracting with private health care companies, and the optimal role of community service providers and diversion programs in providing alternatives to incarceration. Our description of jail health care provides researchers and policymakers a common foundation from which to understand and study the delivery of jail health care and the crucial role that jails hold in the greater system of community health care providers.

Funding/Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD012469. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

Acknowledgments: We thank the study participants who made this project possible. We would like to acknowledge Marisa Domino for her feedback on study design and interview guide development, Sheila Burns for her assistance with data collection, and Priya Sridhar for her assistance with data analysis.

Supporting information

Appendix. Southern Jail Health Care Project: Semistructured Interview Guide

References

- 1. Zeng Z, Minton TD. Jail Inmates in 2019. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji19.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corrections. Bureau of Justice Statistics website. https://www.bjs.ojp.gov/topics/corrections. Published February 18, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare quality and disparities report. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2021qdr.pdf. Published December 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 4. James DJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2004. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/pji02.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones A. New data: the revolving door between homeless shelters and prisons in Connecticut. Prison Policy Initiative website. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/02/10/homelessness. Published February 10, 2021. Accessed January 31, 2022.

- 6. Schoen C, Radley D, Riley P, et al. Health Care in the Two Americas: Findings From the Scorecard on State Health System Performance for Low‐Income Populations, 2013. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2013. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2013_sep_1700_schoen_low_income_scorecard_full_report_final_v4.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high‐income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529‐1540. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):761‐765. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, Berzofsky M. Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse Among State Prisoners and Jail Inmates 2007‐2009. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2017. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/drug‐use‐dependence‐and‐abuse‐among‐state‐prisoners‐and‐jail‐inmates‐2007‐2009. Updated August 10, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. Nov 2009;63(11):912‐919. 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J. Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011‐12, Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf. Updated October 4, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Traumatic brain injury in prisons and jails: an unrecognized problem. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/prisoner_tbi_prof‐a.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2021.

- 13. Hadden KB, Puglisi L, Prince L, et al. Health literacy among a formerly incarcerated population using data from the transitions clinic network. J Urban Health. 2018;95(4):547‐555. 10.1007/s11524-018-0276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramaswamy M, Lee J, Wickliffe J, Allison M, Emerson A, Kelly PJ. Impact of a brief intervention on cervical health literacy: a waitlist control study with jailed women. Prev Med Rep. 2017;6:314‐321. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schaenman PS, Davies E, Jordan R, Chakraborty R. Opportunities for Cost Savings in Corrections Without Sacrificing Service Quality: Inmate Health Care. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2013. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/opportunities‐cost‐savings‐corrections‐without‐sacrificing‐service‐quality‐inmate‐health‐care. Accessed April 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Search ACA accredited facilities. American Correctional Association website. https://www.aca.org/ACA/ACA_Member/Standards_and_Accreditation/SAC_AccFacHome.aspx?WebsiteKey=139f6b09‐e150‐4c56‐9c66‐284b92f21e51&hkey=f53cf206‐2285‐490e‐98b7‐66b5ecf4927a&5940f470ebf4=2#5940f470ebf4. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- 17. James N. Offender Reentry: Correctional Statistics, Reintegration Into the Community, and Recidivism. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2015. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL34287.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelsey CM, Medel N, Mullins C, Dallaire D, Forestell C. An examination of care practices of pregnant women incarcerated in jail facilities in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(6):1260‐1266. 10.1007/s10995-016-2224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shalev N, Chiasson MA, Dobkin JF, Lee G. Characterizing medical providers for jail inmates in New York state. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):693‐698. 10.2105/ajph.2010.198762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rohrer B, Stratton TP. Continuum of care for inmates taking psychiatric medications while incarcerated in Minnesota County jails. J Correct Health Care. 2017;23(4):412‐420. 10.1177/1078345817727283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solomon L, Montague BT, Beckwith CG, et al. Survey finds that many prisons and jails have room to improve HIV testing and coordination of postrelease treatment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3):434‐442. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamath J, Temporini H, Quarti S, et al. Best practices: disseminating best practices for bipolar disorder treatment in a correctional population. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(9):865‐867. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.9.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]