Abstract

The isolation and identification of the 87A strain of epidemic hepatitis E virus (HEV) by means of cell culturing have been described previously. This paper reports the successful isolation of a sporadic HEV strain (G93-2) in human lung carcinoma cell (A549) cultures. The etiology, molecular and biological properties, and serological relationship of this new strain to other, epidemic HEV strains are described. The propagation of both sporadic and epidemic HEV strains in a cell culture system will facilitate vaccine research.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the causative agent of hepatitis E (HE). HE occurs in sporadic and epidemic outbreak forms, mainly in developing nations (2), while occurrence is rare in developed nations (14). In China, a large epidemic occurred between 1986 and 1988 in Xinjiang (7), and sporadic cases were found in other regions. HEV is a nonenveloped virus, is approximately 27 to 34 nm in diameter, and has a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 7.2 kb. The viral genome consists of three discontinuous, partially overlapping open reading frames (ORFs); ORF1 encodes nonstructural gene products, ORF2 encodes the putative capsid protein, and ORF3 encodes a small protein of unknown function (6, 15). HEV is tentatively classified as a member of the Caliciviridae (12).

Since the molecular cloning and sequencing of HEV were described (15), several genomic analyses of HEV strains obtained from different geographic areas have been reported (6). It was reported that there were about 7% nucleotide variations among HEV strains obtained from different countries in Asia (2) and about 25% nucleotide variations between the Asian strains and the Mexican strain (6). It was reported that there was 98.5% nucleotide sequence homology between sporadic and epidemic HEV strains in Myanmar (1). However, existing variations in the gene structure of HEV strains from some regions of China were reported by us (10). Recently, results similar to ours were reported in other studies (5, 17, 18).

Since we found that the genomes of HEV strains in the Guangzhou region contained variations, we carried out further identification of viruses isolated from patients with sporadic HE in the Guangzhou region. Understanding of the characteristics of these strains with regard to biological properties, molecular properties, and serological relationships will lay a foundation for HE vaccine research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains.

Four virus strains, designated G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4, were originally isolated in the A549 cell line from the feces of four patients with acute HE at Guangzhou Municipal Infectious Diseases Hospital in 1993. Detailed information has been reported elsewhere (17).

Cells.

The A549 cell line was prepared in aseptic bottles. The cells were grown in mixed medium (50% medium 199 and 50% Dulbecco modified Eagle medium) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 50 U of kanamycin per ml at 37°C. The medium used for virus culturing was 5 ml of maintenance medium containing 2% inactivated calf serum and 30 mM MgCl2 (final concentration); other components were the same as in growth medium (9). In addition, strain 2BS, a diploid strain of human fetal lung fibroblasts, was obtained from the Beijing Institute of Biological Products and used for passages 26 to 33 in this study. The LLC-MK2 continuous cell line was also used. Culture media and methods used for these cells were the same as those described elsewhere (9).

Antibodies.

Anti-HEV rabbit serum and mouse ascitic fluid were prepared in our laboratory. Titers of polyclonal antibodies obtained by 4 weeks postimmunization were 1:640 and 1:2,560, and those of monoclonal antibodies (e.g., B4C) were 1:1,600 and 1:12,800, as determined by an indirect immunofluorescence assay and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, respectively.

Virus passage.

Briefly, viruses were inoculated onto a monolayer of A549 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.025, and then maintenance medium was added. The inoculated cell monolayer was incubated at 37°C and observed for cytopathic effect (CPE) daily. When the CPE reached +++, both cells and supernatants were harvested and stored.

Virus titration.

After serial 10-fold dilutions were made in growth medium, 0.025 ml of each different dilution was inoculated into four wells each containing 0.025 ml of growth medium, and then 0.5 ml of a cell suspension was added. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere and observed for CPE daily for 7 days. Viral titers were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (13a) and expressed as 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/0.025 ml.

Conditions for virus culturing and the cell sensitivity test.

To select the best propagation conditions, we used an L9(34) positive-cross design. Three factors and three levels were selected to conduct the test: the final concentration of Mg2+ was 0, 30, or 60 mM; the pH value was 6.8, 7.2, or 7.6; and the inoculum dose had an MOI of 0.25, 0.025, or 0.0025. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 72 h and observed for CPE, and viral titers were determined by microculturing after the cell suspension had been frozen and thawed. The results were analysed with SAS software.

For a comparison of sensitivity in different cells, viruses were inoculated into 2BS, A549, and LLC-MK2 cells at an MOI of 0.025. The cells were cultivated in series for three generations and harvested when the CPE reached +++ or on day 7 if the cells were negative for CPE. Viral titers prepassage and postpassage were determined with A549 cells.

Physical and chemical tests.

Passage 8 suspensions of strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 were tested for resistance to acid (pH 3.0), ether, and heat (56°C) and for nucleic acid type. The methods used were the same as those reported previously (19).

Electron microscopy.

Passage 4 of HEV strain G93-2 was inoculated into A549 cell monolayers. Thin sections were prepared as previously described (7). Briefly, HEV strain G93-2 was inoculated into A549 cells at 0.1 ml of virus stock per flask. After the appearance of CPE in infected cell cultures, the medium was harvested, frozen-thawed five times, and centrifuged at 2,600 × g for 40 min to remove debris. After centrifugation (6,000 × g, 30 min), the suspension was precipitated with 8% polyethylene glycol (PEG) at 4°C overnight. The bottom sediment was suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The viral suspension was incubated at 37°C for 1 h with an equal volume of ascitic fluid (1:8 or 1:16) and then at 4°C overnight, with centrifugation (12,500 × g, 30 min) pre- and postincubation. The virus-antibody complex was suspended once more in pure water, applied to carbon-coated grids, negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstate (pH 7.2), and observed and photographed with a Philips CM 120 electron microscope (12).

Identification of the partial genome.

Cell cultures (10 ml) of strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 (passage 5) were concentrated to 0.1 ml with PEG. RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described (13). After denaturation for 10 min at 70°C, reverse transcription and PCR were performed. Two sets of sense and antisense synthetic oligonucleotide primers for the HEV ET1.1 region were used for detection of the HEV genome. The sequences of the primers used in this study were as follows: F1, 5′-GCT ATT AGT GAG GAG TGT GG-3′ (positions 4459 to 4478); R1, 5′-CAG GGC CCC AAT TCT TCT-3′ (positions 4876 to 4859); F2, 5′-GCG TGG ATC TTG CAG GCC-3′ (positions 4522 to 4539); and R2, 5′-TTC AAC TTC AAG CCA CAG CC-3′ (positions 4760 to 4741). The other reactions were the same as those previously described (10). The PCR products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. In order to confirm the specificity of the segments amplified by PCR, Southern blotting was carried out with a 239-bp DNA fragment obtained from HEV strain 87A as a probe. The recovered DNA was ligated with the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega) and transformed in JM109. Positive clones were screened by PCR and identified with EcoRI and HindIII. Positive recombinants were analyzed with an ABI model 373A DNA sequencer. The homology of this part of the nucleotide sequence was compared among strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 and Xinjiang strain 87A (7).

RESULTS

Virus passage.

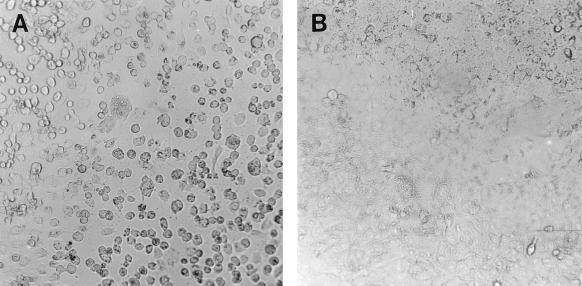

Cell isolation stocks (0.1 ml; passage 1) of strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 were inoculated into A549 cells and incubated at 37°C. CPE was visible at day 2 postinoculation for all four strains. The cell rounding and monolayer destruction were typical characteristics of the CPE produced by the viruses (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(A) CPE produced by HEV strain G93-2 in monolayers of A549 cells at 48 h postinfection. (B) Control A549 cells at 48 h. Magnification, ×200.

Conditions for virus culturing.

Analysis with SAS software of virus propagation in A549 cells revealed that the best propagation conditions were 30 mM Mg2+, pH 7.2, and related to the virus inoculation dose (Table 1). Mg2+ at 30 mM was necessary and very important.

TABLE 1.

Best conditions for propagating HEV strain G93-2 in A549 cells

| Test group | Culture

conditions

|

CPEa | TCID50/0.025 ml | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg2+ concn (mmol/liter) | pH | Inoculum dose (MOI) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 6.8 | 0.25 | ++ | 4.2 |

| 2 | 0 | 7.2 | 0.025 | + | 3.5 |

| 3 | 0 | 7.6 | 0.0025 | − | 1.5 |

| 4 | 30 | 6.8 | 0.025 | ++++ | 5.67 |

| 5 | 30 | 7.2 | 0.0025 | ++++ | 5.83 |

| 6 | 30 | 7.6 | 0.25 | ++++ | 5.23 |

| 7 | 60 | 6.8 | 0.0025 | − | 2.0 |

| 8 | 60 | 7.2 | 0.25 | +++ | 5.0 |

| 9 | 60 | 7.6 | 0.025 | − | 2.5 |

−, no cells showing CPE; +, 25% of the cells show CPE; ++, 50% of the cells show CPE; +++, 75% of the cells show CPE; ++++, 100% of the cells show CPE.

Cell sensitivity.

Results of cell sensitivity testing revealed that 2BS and A549 cells were sensitive to strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 but that LLC-MK2 cells were not (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cell sensitivity testing of the four Guangzhou HEV strains

| Virus strain (passage) | Viral titer

(TCID50/0.025 ml)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepassage | Postpassage in the following cells:

|

|||

| A549 | 2BS | LLC-MK2 | ||

| G93-1 (4) | 5.5 | 5.83 | 5.5 | 0 |

| G93-2 (4) | 4.67 | 5.67 | 5.33 | 0 |

| G93-3 (4) | 5.5 | 5.67 | 6.0 | 0 |

| G93-4 (4) | 5.5 | 5.22 | 5.77 | 0 |

The titer was determined before and after three generations in A549 cells.

Physicochemical properties.

Nucleic acid type, ether sensitivity, acid (pH 3.0) resistance, and heat (56°C, 30 min) stability for passage 8 strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 were determined by a microculture titration method with A549 cells (Table 3). The results for strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 were similar; the viruses are unenveloped RNA virus particles not resistant to acid (pH 3.0) or heat (56°C, 30 min).

TABLE 3.

Results of physicochemical testing of the four Guangzhou HEV strains

| Test group | Titer (TCID50/0.025 ml) of

the following virus straina:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G93-1 | G93-2 | G93-3 | G93-4 | |

| Nucleic acid | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 6.5 |

| Ether | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 |

| Acid (pH 3.0) | 1.3 | <1.0 | 1.3 | <1.0 |

| Heat (56°C, 30 min) | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| Virus control | 6.3 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 6.7 |

The titer was determined in A549 cells.

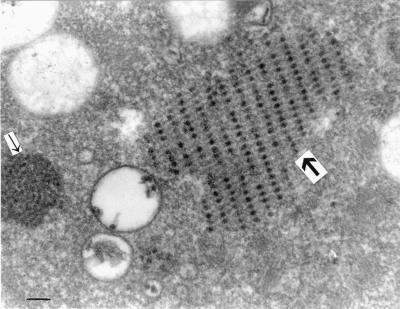

Electron microscopy observations.

Ultrastructural changes were mainly found in the cytoplasm of an infected cell. Virus particles of the four strains examined were arranged in the form of a crystal. Clusters contained several to hundreds of particles. The virion was round, approximately 25 to 36 nm in diameter. The surface of the virus was irregular. Empty particles were embedded in the crystal structure of completely mature viruses. Viral inclusion bodies and vacuoles were observed near the crystal (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Electron micrograph of cells infected by strain G93-2 showing a typical crystalline array of virus particles (large arrow) in infected cellular cytoplasm, vacuoles, and a viral inclusion body nearby (small arrow). Bar, 100 nm.

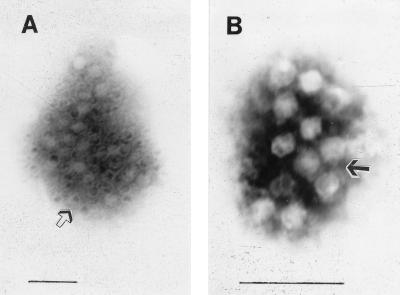

Immunoelectron microscopy.

The virus particles of strain G93-2 could be identified by use of serum from a rabbit immunized with strain G93-2 or 87A and mouse hybridoma ascitic fluid derived from strain 87A (Fig. 3). The virus particles were all aggregated into clusters. Antibody bridge and antibody coat were found occasionally in some particles. Although aggregates of virus particles could occur in both HEV strains with polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, the numbers in clusters of strain G93-2 were smaller than those in clusters of strain 87A. The efficiency of capture of virus particles by monoclonal antibodies was also lower than that by polyclonal antibodies. A 1:40 dilution of serum could be used for the capture of particles, while only a 1:16 dilution of ascitic fluid could be used. These results showed that strain G93-2 in Guangzhou and epidemic strain 87A in Xinjiang are closely related serologically.

FIG. 3.

Immunoelectron micrograph of HEV strain G93-2 captured by antibody. Virus particles were aggregated into clusters captured by B4C ascitic fluid (A) and captured by immunized-rabbit serum (B). Empty particles (open arrow) and antibody coat (filled arrow) are also shown. Staining was done with 2% phosphotungstate (pH 7.4). Bars, 100 nm.

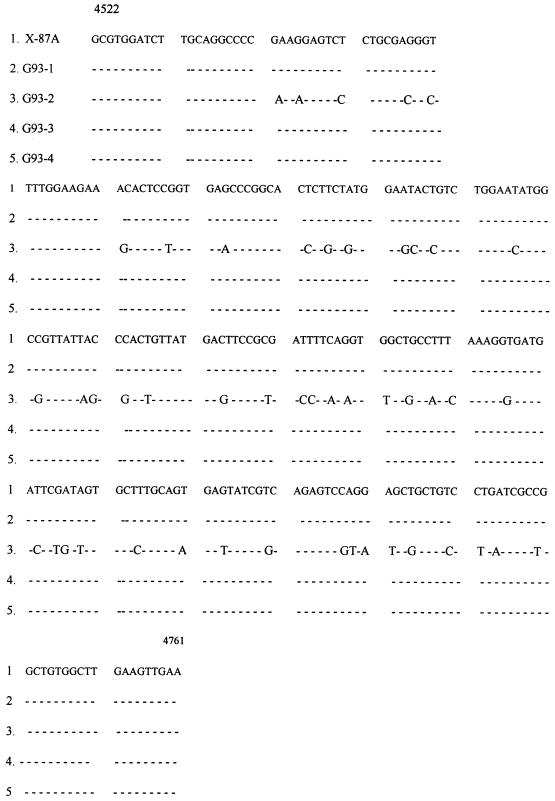

Partial genome determination.

When RNA from strains G93-1, G93-2, G93-3, and G93-4 as the template was amplified with primers for the HEV ET1.1 region, a band of approximately 239 bp was observed by gel electrophoresis. The PCR results for these four strains were confirmed by Southern blotting with a 239-bp probe from HEV strain 87A. After cloning, nucleotide sequencing analysis of the PCR fragments derived from the virus strains was done (Fig. 4). The nucleotide sequence homologies in this part of the genome were 79.9% between strains G93-2 and 87A and 100% among strains G93-1, G93-3, and G93-4 and strain 87A.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of partial nucleotide sequences of the four Guangzhou strains and strain 87A. Dashes indicate identity.

DISCUSSION

Four HEV strains were isolated from four patients with sporadic HE in Guangzhou, China. The results suggested that A549 cells could be used to isolate and cultivate HEV. In addition, some continuous cell lines, such as 2BS, Hep-G2, and PLC-PRF-5, derived from human lung or liver, are susceptible to HEV (4, 7, 11, 13). The CPEs in both the 2BS and the A549 cell lines were certainly produced by the HEV infection. Those CPEs could be specifically neutralized by antibodies derived from sera from patients with HE, antibody from immunized-rabbit serum, and mouse ascitic fluid (data not shown). HEV also could be cultivated in in vivo-infected primary macaque hepatocytes, but no CPE was observed (16). CPE occurrence may be mainly related to the in vitro cell culture system used for HEV.

There are two reasons for the successful culturing of HEV in both 2BS and A549 cells. First, the stool suspension should be precipitated with PEG. Second, 30 mM MgCl2 must be added to the culture medium in order to increase the titers of virus and protect viral infectivity from inactivating factors. This is a very important approach to resolving the problem of few HEV particles in acute-phase specimens. Therefore, the high level of isolation of HEV (four of eight) is mostly attribute to PEG and Mg2+. In addition, specimens should be isolated within 6 months of collection; otherwise, isolation will not succeed because of the lengthy preservation time (data not shown).

Four HEV strains from Guangzhou, southern China, were similar to strain 87A from Xinjiang, western China, in physical, chemical, and biological properties and morphology. Strain G93-2, isolated in southern China, could be recognized by both polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against HEV strain 87A, isolated from an epidemic in western China, by immunoelectron microscopy. Therefore, these virus strains are closely related serologically.

On the basis of full-length or partial nucleotide sequences of HEV reported in many developing countries or areas in Asia since 1990, many scientists consider that the homology of HEV strains in Asia is comparatively high and that there is 75% homology between HEV strains in Asia and Mexico. Therefore, HEV may have two different subtypes or genotypes. In this report, a portion of the sequence of HEV strains G93-1, G93-3, and G93-4 was similar to those of Xinjiang strain 87A in China and a Burmese strain, but strain G93-2 was different from Xinjiang strain 87A, the Burmese strain, and a Mexican strain, with homologies of 79.9, 79.9, and 77.4%, respectively. A recent study suggested that a portion of the sequence of strain G93-2 has 99.2% homology with fragments from serum from a patient with HE (China X-S1) in Xiamen, which is near Guangzhou (8). Thus, there is a new HEV genotype in China besides the Burmese and Mexican genotypes. We expressed this view in 1995 (10). Later, other investigators reported similar results (5, 17, 18). Recently, American scientists reported that strain US-1 was not similar to Asian strains or to the Mexican strain (14) and that Moroccan strains were close to Asian strains (3). Consequently, the sequences of HEV from various areas showed that the differences among HEV strains correlate with geographic location.

HEV has been provisionally described as a Calicivirus-like virus (12, 15). The size, morphology, and physicochemical properties reported in this study strongly support the notion that it is a member of the Caliciviridae.

Our results may provide candidate strains for the study of a Chinese HE vaccine. On the assumption that there might be only one serotype of HEV in Asia, selecting strain 87A or the four Guangzhou strains as candidate strains for a vaccine will be of significance for the prophylaxis and treatment of HE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank N. Q. Chen, J. J. Wang, and X. B. Xia, Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, for assistance in this study and X. K. Ma for proofreading.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aye T T, Uchida T, Ma X, Iida F, Shikata T, Ichikama M, Rikihisa T, Win K M. Sequence and gene structure of the hepatitis E virus isolated from Myanmar. Virus Genes. 1993;7:95–110. doi: 10.1007/BF01702352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley D W. Hepatitis E: epidemiology, aetiology and molecular biology. Rev Med Virol. 1992;2:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chattenjee R, Tsarev S, Pillot J, Coursagat P, Emeron S U, Purell R H. African strains of hepatitis E virus that are distinct from Asian strains. J Med Virol. 1997;5:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W R, Tian X, Bao Z Y, Li J Y, Deng D R. Partial genome sequence analysis of hepatitis E virus isolated by cell culture. Chin Virol. 1994;9:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh S Y, Yang P Y, Ho Y P, Chu C M, Liaw Y F. Identification of a novel strain of hepatitis E virus responsible for sporadic acute hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1998;55:300–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<300::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C C, Nguyen D, Fernandez J, Yun K Y, Fry K E, Bradley D W, Tam A W, Reyes G R. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the Mexico isolate of hepatitis E virus (HEV) Virology. 1992;191:550–558. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90230-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang R T, Li D R, Wei J, Huang X R, Yuan X T, Tian X. Isolation and identification of hepatitis E virus in Xinjiang, China. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1143–1148. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang R T, Li X Y, Xia X B, Yuan X T, Li D R. Antibody detection and genome analysis of sporadic HEV in Xiaman region. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:270–272. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang R T, Nakazono N, Ishii K, Li D R, Kawamata O, Kawaguch R, Tsukada Y. Hepatitis E virus (87A strain) propagated in A549 cells. J Med Virol. 1995;47:299–302. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang R T, Nakazono N, Ishii K, Kawamata O, Kawaguch R, Tsukada Y. Existing variations on the gene structure of hepatitis E virus from some regions of China. J Med Virol. 1995;47:303–308. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D R, Huang R T, Pang J J, Yuan X T, Li X Y. Biological feature and genome analysis of HEV isolated by cell-culture. In: Coursaget P, Buisson Y, Kane M, editors. Enterically-transmitted hepatitis viruses. 1996. pp. 349–361. La Simarre, Tours, France. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D R, Huang R T, Tian X, Yin S R, Wei J, Huang X R, Wang B Z, Li R X, Li Y C. Morphology and morphogenesis of hepatitis E virus (strain 87A) Chin Med J. 1995;108:126–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng J H, Dubreuil P, Pillot J. A new PCR-based seroneutralization assay in cell culture for diagnosis of hepatitis E. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1373–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1373-1377.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Reed L, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent end point. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–495. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlauder G G, Dawson G J, Erker J C, Kwo P Y, Kningge F, Smalley D L, Rosenblatt J E, Desai S M, Mushahwar I K. The sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a novel hepatitis E virus isolated from a patient with acute hepatitis reported in the United States. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:447–456. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-3-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam A W, Smith M M, Guerra M E, Huang C C, Bradley D W, Fry K E, Reyes G R. Hepatitis E virus (HEV): molecular cloning and sequencing of the full length viral genome. Virology. 1991;185:120–131. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90760-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam A W, White R, Reed E, Short M, Zhang Y, Fuerst T R, Lanford R E. In vitro propagation and production of hepatitis E virus from in vivo-infected primary macaque hepatocytes. Virology. 1996;215:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei S J, Walsh P, Yangbo T, Dong H Q, Cai X L. Nucleic acid sequence analysis of the sporadic hepatitis E virus strains in Guangzhou. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1998;18:92–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J C, Sheen I J, Chiang T Y, Sheng W Y, Wang Y J, Chan C Y, Lee S D. The impact of traveling to endemic areas on the spread of hepatitis E virus infection: epidemiological and molecular analyses. Hepatology. 1998;27:1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu G F, Huang R T, Ding J H, Li D R, Jiang G R, Wang J. Micro cell culture for the detection of dengue viruses. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1982;2:219–222. [Google Scholar]