Abstract

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has not been managed and controlled globally. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to determine the global pro-vaccination attitude and associated factors towards COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers (HCWs) and nonhealthcare workers (non-HCWs).

Methods

Different databases such as PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, and Google Scholar were used. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flowchart diagram and PRISMA checklist were used for study screening, selection, and inclusion into this systematic review and meta-analysis. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment criteria for cross-sectional studies were used to assess the included articles.

Results

A total of 51 studies were included into this systematic review and meta-analysis. The meta-analysis revealed that the global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 61.30% (95%CI: 56.12, 66.47, I2 = 99.8%: p=0.000). Subgroup analysis showed that the global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine was the lowest (59.77%, 95%CI (51.56, 67.98); I2 = 99.6%, p=0.000) among the HCWs participants and the highest (62.53%, 95%CI (55.39, 69.67); I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) among the non-HCWs participants and the lowest (54.31%, 95%CI (43, 65.63); I2 = 99.5%, p=0.000) for sample size <700 and the highest (66.49%, 95%CI (60.01, 72.98); I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for sample size >700; the lowest (60.70%, 95%CI (54.08, 67.44); I2 = 93.0%, p=0.000) for studies published in 2020 year and the highest (61.31%, 95%CI (55.93, 66.70); I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for the studies published after 2020 years. From this systematic review, factors significantly associated with pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs were such as age, gender, race, work experience, home location, having no fear of injections, being a non-smoker, profession, presence of chronic illnesses, allergies, confidence in pharmaceutical companies, history of taking influenza vaccine, vaccine recommendation, perceived risk of new vaccines, perceived utility of vaccine, receiving a seasonal flu vaccination in the last 5 years, working in a private hospital, a high perceived pandemic risk index, low vaccine harm index, high pro-socialness index, being in close contact with a high-risk group, knowledge about the virus, confidence in and expectations about personal protective equipment, and behaviors. The level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs ranged from 21.40% to 91.99%. Factors associated with the attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs were such as age, gender, educational level, occupation, marital status, residency, income, ethnicity, risk for severe course of COVID-19, direct contact with COVID-19 at work, being a health profession, being vaccinated against seasonal flu, perceived benefits, cues to actions, having previous history of vaccination, fear of passing on the disease to relatives, and the year of medical study, studying health-related courses, COVID-19 concern, adherence level to social distancing guidelines, history of chronic disease, being pregnant, perceived vaccine safety, having more information about vaccine effectiveness, mandatory vaccination, being recommended to be vaccinated, lack of confidence in the healthcare system to control epidemic, and belief in COVID-19 vaccines protection from COVID-19 infection.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that the global estimated pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was unsatisfactory. Globally, there is a need for a call for action to cease the crisis of this pandemic.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic has spread quickly over all countries. This pandemic affects all age categories of the population globally [1]. COVID-19 remains as a large burden to the world, and it continues to ravage the world [2]. This pandemic has put a challenge across all countries [3], since it was stated as a pandemic [4]. COVID-19 is a disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a worldwide public emergency [5]. COVID-19 pandemic has become one of the central health crises of a generation. This pandemic has affected all persons globally [6].

COVID-19 puts a significant burden comprising morbidity and mortality [7, 8]. It has also led to substantial economic disasters besides mortality and morbidity [9]. This pandemic has also led to mental health worsening of the families who had children [10], the entire population [11], and an enormous effect on mental health of the youth [12]. It has also affected the development of children [13] and interrupted the vaccination of children [14]. Furthermore, this pandemic also has momentous stress on patients, healthcare systems, and HCWs [15]. It has also affected the treatment and prevention of chronic cases such as tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus [16]. COVID-19 had put an extensive problem on the African continent [17], a poor and susceptible population [9].

Thus, urgent measures across all countries have been necessitated because of the substantial morbidity and socioeconomics of this pandemic [18]. Because of a lack of vaccine, diverse prevention approaches were executed. Testing, contact tracing, and social restrictions are among the most powerful approaches adopted globally [19]. For instance, several measures are being implemented by the African countries, including school closures, travel bans, limits to large gatherings, increased testing, and country lockdown [9].

In high-income countries or regions, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy remains a highly prevalent problem. Being younger, females, non-Whites, and having lower education or income level were more prone to vaccine hesitancy. Furthermore, factors associated with vaccine hesitancy were history of not receiving influenza vaccination, a lower self-perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, a lesser fear for health outcomes or COVID-19, not believing in the severity of COVID-19, having concerns about the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines as well as disbeliefs in the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines [20].

A vaccine offers the greatest hope for a permanent solution to control it [2]. Since COVID-19 is continuing its impact all over the country, the government should be equipped to distribute a COVID-19 vaccine accordingly [21]. The intention for a vaccine against COVID-19 is determined by the information concerning to the people variety, vaccine efficacy, and vaccine development [22]. Since there are controversies regarding the safety and efficacy of this vaccine, this may decline the vaccination rates [23]. Vaccine hesitancy may lead to the decrement in the need of the population for a COVID-19 vaccine [24]. Besides, people unwillingness for this vaccine will determine the COVID-19 response and public health benefits of an effective vaccine [25]. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine will be tested by vaccine hesitancy [26]. Only a small proportion of the parents had agreed to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 [27]. About one-third of the caregivers were reluctant to vaccinate their children [28]. The parents are not agreed to join their child, even in a clinical trial for this vaccine [29]. This would delay the time of the pandemic, because all these factors affect the attainment of herd immunity to this pandemic [30].

Knowing the intention of this vaccine will assist in the application of effective methods to improve this vaccination [31]. Lessening vaccination hesitancy concerning COVID-19 to control it may be as notable as determining a safe and effective vaccine [32]. It is an ethical and humanistic responsibility to approve that this vaccine is safe for the public [33]. It is vital to permit HCWs and the community to have access to reliable and satisfactory evidence about this vaccine to increase its acceptance rate [34]. The attitude of the HCWs regarding COVID-19 vaccine affects themselves to use the vaccine and their willingness to recommend for the patients. Therefore, future education should prioritize for HCWs to the population to accept it [35]. HCWs who refuse to have vaccination are often accused of exposing their patients to a lethal infection [36]. It is acceptable that vaccines are very significant population health measures to defend individuals from this pandemic. Besides, HCWs accounted for a considerable figure of infected individuals [37].

The development of SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine puts in itself a new test for governments and health authorities [38]. HCWs are at high risk of COVID-19 [39, 40]. The pandemic among these populations is a main worry for health authorities worldwide. While COVID-19 infection in HCWs would have an instant consequence on their occupation and the whole healthcare system [39]. Protecting the HCWs from COVID-19 would be critical to preserve healthcare systems [37]. A vaccine must be acknowledged and used by the population to be effective [2]. Developing trust between communities and the intention to take COVID-19 vaccine is as significant as producing a safe and effective vaccine to control this pandemic [41]. The study revealed that the decrease in COVID-19 cases among HCWs started after anti-COVID-19 vaccination, which reveals that COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing infection [42].

1.1. Research Questions

What is the global pooled prevalence of positive pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs?

What are the factors associated with the level of positive pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting

Studies done across worldwide were included in to this systematic review and meta-analysis.

2.2. Search Strategies

Different databases such as PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were used to search the related articles. During this, the search was done for articles published until August 31, 2022. Search terms used were; COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, novel coronavirus, nCoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, coronavirus disease 2019 virus, 2019-nCoV, 2019 novel coronavirus, coronavirus, attitude, factors, associated factors, healthcare workers, nurses, midwives, physician, health professional, healthcare providers, and vaccine. Boolean operators' strings were used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search databases and strategies about the HCWs and non-HCWs Pro-vaccination Attitude and Its Associated Factors Towards COVID-19 Vaccine.

| Database | Search strategies |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“COVID-19”[All fields] OR “COVID-19”[MeSH terms] OR “COVID-19 vaccines”[All fields] OR “COVID-19 vaccines”[MeSH terms] OR “COVID-19 serotherapy”[All fields] OR “COVID-19 serotherapy”[Supplementary concept] OR “COVID-19 nucleic acid testing”[All fields] OR “COVID-19 nucleic acid testing”[MeSH terms] OR “COVID-19 serological testing”[All fields] OR “COVID-19 serological testing”[MeSH terms] OR “COVID-19 testing”[All fields] OR “COVID-19 testing”[MeSH terms] OR “SARS CoV 2”[All fields] OR “SARS CoV 2”[MeSH terms] OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[All fields] OR “nCoV”[All fields] OR “2019 nCoV”[All fields] OR ((“coronavirus”[MeSH terms] OR “coronavirus”[All fields] OR “CoV”[All fields]) AND 2019/11/01 : 3000/12/31[date - publication])) AND (“attitude”[MeSH terms] OR “attitude”[All fields] OR “attitudes”[All fields] OR “attitude s”[All fields])) OR (“factor”[All fields] OR “factor s”[All fields] OR “factors”[All fields])) AND (“health personnel”[MeSH terms] OR (“health”[All fields] AND “personnel”[All fields]) OR “health personnel”[All fields] OR (“healthcare”[All fields] AND “workers”[All fields]) OR “healthcare workers”[All fields]) AND (“vaccine”[Supplementary concept] OR “vaccine”[All fields] OR “vaccination”[MeSH terms] OR “vaccination”[All fields] OR “vaccinable”[All fields] OR “vaccinal”[All fields] OR “vaccinate”[All fields] OR “vaccinated”[All fields] OR “vaccinates”[All fields] OR “vaccinating”[All fields] OR “vaccinations”[All fields] OR “vaccination s”[All fields] OR “vaccinator”[All fields] OR “vaccinators”[All fields] OR “vaccine s”[All fields] OR “vaccinated”[All fields] OR “vaccines”[MeSH terms] OR “vaccines”[All fields] OR “vaccine”[All fields] OR “vaccines”[All fields]) |

|

| |

| EMBASE | “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “nCoV” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “coronavirus disease 2019 virus” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “2019 novel coronavirus” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR “coronavirus AND “attitude” OR “factors” OR “associated factors” AND “healthcare workers” OR “nurses” OR “midwifes” OR “physician” OR “health professional” OR “healthcare providers” AND “vaccine” |

|

| |

| Scopus | “COVID-19∗” OR “SARS-CoV-2∗” OR “novel coronavirus∗” OR “nCoV∗” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2∗” OR “coronavirus disease 2019 virus∗” OR “2019-nCoV∗” OR “2019 novel coronavirus∗” OR “coronavirus∗” AND “attitude∗” OR “factors∗” OR “associated factors∗” AND “healthcare workers∗” OR “nurses∗” OR “midwifes∗” OR “physician∗” OR “health professional∗” OR “healthcare providers∗” AND “vaccine∗” |

|

| |

| Web of Science | (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR novel coronavirus OR nCoV OR severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR coronavirus disease 2019 virus OR 2019-nCoV OR 2019 novel coronavirus OR severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR coronavirus) AND attitude AND factors OR associated factors AND (healthcare workers OR nurses OR midwives OR physician OR health professional OR healthcare providers) AND vaccine |

|

| |

| Google Scholar | COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR novel coronavirus OR nCoV OR severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR coronavirus disease 2019 virus OR 2019-nCoV OR 2019 novel coronavirus OR coronavirus AND attitude AND factors OR associated factors AND healthcare workers OR nurses OR midwives OR physician OR health professional OR healthcare providers AND vaccine |

3. Eligibility Criteria

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included into the systematic review and meta-analysis if they fulfil: cross-sectional studies which reported outcome variables, articles done among adults, and articles published in English language, and articles published up to August 31, 2022, across all countries.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles which did not assess the outcome variables, articles which were not fully accessible, articles published in non-English language, and articles with poor quality were excluded from this systematic review and meta-analysis.

3.3. Outcome Interest

In this systematic review, the primary outcome was the prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs. Pro-vaccination attitude refers to the attitudes of the participants regarding to the COVID-19 vaccine, whether or not they take it if available. Pro-vaccination attitude was measured by using an “Yes” or “No” question. “Do you intend to have a COVID-19 vaccine in the future?” was the question asked to the participants. The secondary outcome was factors associated with pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs which was reported within the included studies.

3.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The retrieved articles from all databases were exported to Thomson Reuters EndNote version 8. The titles and abstract of all possible articles to be included in this systematic review were checked. The standardized data extraction format prepared in a Microsoft Excel worksheet was used to extract the data from the selected articles according to the preset inclusion criteria. The names of the authors, publication year, study period, study country, participants, sample size, study design, prevalence, and factors were used for the extraction of data from each article.

This systematic review has only included cross-sectional studies. The NOS quality assessment criteria for cross-sectional studies were used to assess the included articles [43, 44], and the modified NOS for cross-sectional studies was used to include the articles. Whereas, all articles with ≥5 out of 10 were considered as a high-quality score [45], and included in to this systematic review and given as (supplementary 12 file). The NOS methodological quality assessment score has been included for each article (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis on the level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs over different countries.

| S. N | Authors | Year | SP | Country | Participants | SS | SD | Level (%) | Factors | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Vignier et al. [46] | 2021 | January 22 to March 26, 2021 | France | HCWs | 579 | CS | 65.6 | Confidence in pharmaceutical companies, and confidence in the management of the epidemic. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2. | Alle and Oumer [47] | 2021 | February 5 to March 20, 2021 | Ethiopia | Health professions | 319 | CS | 42.3 | Age and profession. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 3. | Kaur et al. [48] | 2021 | Not explained | India | Medical and dental professionals | 520 | CS | 65 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 4. | Verger et al. [49] | 2021 | October and November 2020 | France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada | HCWs | 2,678 | CS | 48.6 | Age, history of taking influenza vaccine, vaccine recommendation, perceived risk of new vaccines, and perceived utility of vaccine. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 5. | Ahmed et al. [50] | 2021 | Not explained | Saudi Arabia | Healthcare providers | 236 | CS | 55.5 | Sex, age, presence of chronic illnesses, and allergy. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6. | Fakonti et al. [51] | 2021 | December 8 to 28, 2020 | Cyprus | Nurses and midwives | 437 | CS | 30 | Receiving a seasonal flu vaccination in the last 5 years, recommended vaccines for health professionals, and working in a private hospital. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 7. | Chew et al. [52] | 2021 | December 12 to 21, 2020 | Asia-Pacific | HCWs | 1720 | CS | 95 | A high perceived pandemic risk index, low vaccine harm index and high pro-socialness index. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 8. | Guangul et al. [53] | 2021 | Not explained | Ethiopia | HCWs | 668 | CS | 72.2 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 9. | Nasir et al. [54] | 2021 | In February 2021 | Bangladesh | HCWs | 550 | CS | 70.23 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 10. | Paudel et al. [55] | 2021 | January 27 to February 3, 2021. | Nepal | HCWs | 266 | CS | 38.3 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 11. | Baghdadi et al. [56] | 2021 | July to September 2020 | Saudi Arabia | HCWs | 356 | CS | 61.16 | Gender, age (middle aged), work experience (<5 years), having no fear of injections, and being a non-smoker. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 12. | Di Gennaro et al. [57] | 2021 | 1 October to 1 November 2020 | Italy | HCWs | 1723 | CS | 67 | Being a non-MD health professional, using Facebook as main information source about antiSARS-CoV-2 vaccination, being a younger, age (<30 years), being in close contact with a high-risk group, and having undertaken seasonal flu vaccine during the 2019–2020 season. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 13. | Elhadi et al. [58] | 2021 | December 1 to 18, 2020 | Libya | Physicians and paramedic | 2215 | CS | 58.19 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 14. | Ciardi et al. [59] | 2021 | December 10, 2020 to January 5, 2021 | New York | HCWs | 428 | CS | 64 | Gender, age, race, home location, role within the hospital, knowledge about the virus, and confidence in and expectations about personal protective equipment and behaviors. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 15. | Fares et al. [60] | 2021 | December 2020 to January 2021 | Egypt | HCWs | 385 | CS | 21 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 16. | Harsch et al. [61] | 2021 | Not explained | Germany | HCWs | 200 | CS | 37.5 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 17. | Szmyd et al. [62] | 2021 | December 22, 2020 to January 8, 2021 | Poland | HCWs | 2300 | CS | 82.95 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 18. | Ledda et al. [63] | 2021 | September to December 20, 2020 | Italy | Healthcare personnel | 787 | CS | 75 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 19. | Shaw et al. [64] | 2021 | November 23 to December 5, 2020 | US | Healthcare personnel | 5287 | CS | 57.5 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 20. | Bauernfeind et al. [65] | 2021 | December 12 to 21, 2020 | Germany | Hospital employees | 2454 | CS | 59.5 | Age, gender, educational level, risk for severe course of COVID-19, occupation, direct contact with COVID-19 at work, flu shot in influenza 2019/2020, and flu shot in influenza 2020/2021. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 21. | Spinewine et al. [66] | 2021 | January 6 to 20, 2021 | Belgium | Hospital staffs | 1132 | CS | 62.9 | Being older, being a physician, being vaccinated against seasonal flu, perceived benefits, and cues to actions. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 22. | Mesesle [67] | 2021 | March 13 to April 10, 2021 | Ethiopia | Adult population | 425 | CS | 24.2 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 23. | Islam et al. [68] | 2021 | December 2020 to February 2021 | Bangladesh | Adult population | 1658 | CS | 78 | Being female, and having previous history vaccination. | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 24. | Kasrine Al Halabi et al. [69] | 2021 | November to December 2020 | Lebanon | Adult population | 579 | CS | 21.4 | Gender and marital status. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25. | Szmyd et al. [70] | 2021 | December 22 to 25, 2020 | Poland | Medical students | 632 | CS | 91.99 | Fear of passing on the disease to relatives, and the year of medical study. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 26. | Bai et al. [71] | 2021 | December 27, 2020 to January 18, 2021 | China | College students | 2,881 | CS | 76.3 | Residency (urban), and studying health-related courses. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 27. | Brodziak et al. [72] | 2021 | Not explained | Poland | Cancer patients | 635 | CS | 73.7 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 28. | Akarsu et al. [73] | 2021 | 10/06/2020 and 10/07/2020 | Turkey | Adult population | 759 | CS | 49.7 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 29. | Ward et al. [74] | 2020 | Each week of April 2020 | France | Adult population | 5018 | CS | 76 | Gender, age, COVID-19 concern, and HICU. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 30. | Szmyd et al. [70] | 2021 | December 22 to 25, 2020 | Poland | Nonmedical students | 763 | CS | 59.42 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 31. | Freeman et al. [75] | 2021 | September 24 to October 17, 2020 | UK | Adult population | 5,114 | CS | 71.7 | Younger age, female gender, lower income, ethnicity, and lower adherence to social distancing guidelines. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 32. | Pogue et al. [76] | 2020 | Not explained | United States | Adult population | 316 | CS | 68 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 33. | Paul et al. [77] | 2021 | March 21/2020 | UK | Adult population | 32,361 | CS | 84 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 34. | Cordina et al. [78] | 2021 | 30/10/2020 to 16/11/2020 | Malta | Adult population | 2529 | CS | 50 | Gender(male), and being health profession. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 35. | Alabdulla et al. [79] | 2021 | October 15 to November 15, 2020 | Qatar | Adult population | 7821 | CS | 79.8 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 36. | Chen et al. [80] | 2021 | Not explained | China | Adult population | 3195 | CS | 76.6 | NA | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 37. | La Vecchia et al. [81] | 2020 | September 16 to 28, 2020 | Italy | 15–85 years population | 1055 | CS | 53.7 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 38. | Largent et al. [82] | 2020 | September 14 to 27, 2020 | US | Adult population | 2730 | CS | 61.4 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 39. | El-Elimat et al. [83] | 2021 | November 2020 | Jordan | Adult population | 3,100 | CS | 66.5 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 40. | Graeber et al. [84] | 2021 | June and July 2020 | Germany | Adult population | 851 | CS | 70 | NA | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 41. | Al-Marshoudi et al. [85] | 2021 | December15 to 31, 2020 | Oman | Adult population | 3000 | CS | 59.3 | Gender (male), history of chronic disease, pregnancy, perceived vaccine safety, education levels, and occupation. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 42. | Villarreal-Garza et al. [86] | 2021 | March 12 to 26, 2021 | Mexico | Breast cancer patients | 540 | CS | 66 | Age, having a close acquaintance who did not experience a vaccine-related adverse reaction, having more information about vaccine effectiveness, mandatory vaccination, and being recommended by their oncologist to be vaccinated. | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 43. | Jiang et al. [87] | 2021 | Mid-March 2021 | China | Nursing college students | 1,488 | CS | 70.07 | NA | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 44. | Omar and Hani [88] | 2021 | January 7 to March 30, 2021 | Egypt | Adult population | 1011 | CS | 46 | Gender (female), residence (urban), educational level (university/post graduate), marital status (married), having flu vaccine, and lack of the confidence in the healthcare system to control epidemic. | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 45. | Cai et al. [89] | 2021 | November 27, 2020 and March 12, 2021 | China | Adolescent population | 1,057 | CS | 75.59 | Age (younger), heard about COVID-19 vaccines, believe in COVID-19 vaccines protection from COVID-19 infection, and those who encouraged their family members and friends to get vaccinated, and believing that vaccines are safe. | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 46. | Kuhn et al. [90] | 2021 | December 2020 to January 2021 | USA | PEH | 90 | CS | 52 | NA | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 47. | Petravić et al. [91] | 2021 | December 17 to 27, 2020 | Slovenia | Residents >15 years | 12,042 | CS | 33 | NA | 8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 48. | Kumari et al. [92] | 2021 | March 13 to 25, 2021 | India | ≥18 years population | 1294 | CS | 83.6 | NA | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 49. | Koh et al. [93] | 2022 | May to June | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2021 | Singapore | Primary healthcare workers | 528 | CS | 94.9% | NA | 7 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 50. | AW et al. [94] | 2022 | March to July 2021 | Singapore | HCWs | 241 | CS | 48.5 | Being female, a younger age, not having had a loved one or friend infected with COVID-19 and obtaining information from newspapers | 7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 51. | Kanyike et al. [95] | 2021 | March 15 to 21 2021 | Uganda | Medical students | 600 | CS | 30.7 | NA | 7 |

Notice: SP, study period; SS, sample size; SD, study design; CS, cross-sectional; HCWs, healthcare workers; NA, not applicable; HICU, household income per consumption unit; PEH, people experiencing homelessness.

3.5. Data Processing and Analysis

Random effect model was used to estimate the global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs. The analysis was done by using STATA version 11 statistical software. The heterogeneity of the included articles was assessed by using I2 statistics. The publication bias was measured by using Egger's test. Subgroup analysis was done based on the study participant, publication year, and sample size. Forest plot was used to show the pooled prevalence with 95%Cl.

3.6. Data Synthesis and Reporting

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted on global pro-vaccination attitude and associated factors towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs. During this, PRISMA 2020 flowchart diagram [96], and PRISMA 2020 checklist [96] were used for the study screening, selection, and inclusion in to this systematic review. PRISMA 2020 checklist is given as (supplementary 2 file).

4. Results

4.1. Search Results

All related studies done across the world were identified by using diverse databases. From the search made through the mentioned databases, 10,227 studies were found. From this, only 51 studies were meeting the predefined eligibility criteria and included in to this systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart diagram of the study selection for systematic review on pro-vaccination attitude and associated factors towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and Non-HCWs globally. Note: adopted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. Reference [96].

4.2. Study Characteristics

This systematic review focused on the studies conducted on attitude regarding COVID-19 vaccine and its associated factors among the two major population categories, HCWs and non-HCWs. In this systematic review, a total of 48 studies were included, comprising of studies done on both HCWs and non-HCWs participants. There have been substantial differences concerning the level of attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both populations (Table 2).

4.3. Attitude towards COVID-19 Vaccine among HCWs

From the total of 51 studies included in to this systematic review and meta-analysis, only 23 studies were conducted among HCWs. The smallest and the largest sample sizes were reported from Germany (200) [61], and the United States (US) (5,287) [64], respectively. The smallest prevalence of a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs were reported as 21% from Egypt [60], while the largest prevalence was 95%, which was reported from Asia-Pacific [52]. Thus, the prevalence of a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs ranged from 21% [60] to 95% [52].

Factors significantly associated with the pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs were age, gender, race, work experience, home location, having no fear of injections, being a non-smoker, profession, presence of chronic illnesses, allergies, confidence in pharmaceutical companies, confidence in the management of the epidemic, history of taking influenza vaccine, vaccine recommendation, perceived risk of new vaccines, perceived utility of vaccine, receiving a seasonal flu vaccination in the last 5 years, working in a private hospital, a high perceived pandemic risk index, low vaccine harm index, high pro-socialness index, using Facebook as main information source about antiSARS-CoV-2 vaccination, being in close contact with a high-risk group, having undertaken seasonal flu vaccine during the 2019–2020 season, role within the hospital, knowledge about the virus, confidence in and expectations about personal protective equipment, and behaviors (Table 2).

4.4. Attitude towards COVID-19 Vaccine among Non-HCWs

Concerning to the non-HCWs, a total of 28 studies were conducted among non-HCWs from 48 studies included in to this systematic review. The smallest and the largest sample sizes were reported, 90 from the United States of America [90], and 32,361 from the United Kingdom [77], respectively. The smallest prevalence of a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs were reported as 21.4% from Lebanon [69], while the largest prevalence was 91.99%, which was reported from Poland [70]. Thus, the prevalence of a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs ranged from 21.4% [69] to 91.99% [70].

Factors associated with the attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs were age, gender, educational level, occupation, marital status, residency, income, ethnicity, risk for severe course of COVID-19, direct contact with COVID-19 at work, being a health profession, being vaccinated against seasonal flu, perceived benefits, cues to actions, having previous history of vaccination, fear of passing on the disease to relatives, and the year of medical study, studying health-related courses, COVID-19 concern, adherence level to social distancing guidelines, history of chronic disease, being pregnant, perceived vaccine safety, having a close acquaintance who did not experience a vaccine-related adverse reaction, having more information about vaccine effectiveness, mandatory vaccination, being recommended to be vaccinated, lack of the confidence in the healthcare system to control epidemic, heard about COVID-19 vaccines, belief in COVID-19 vaccines protection from COVID-19 infection, those who encouraged their family members and friends to get vaccinated (Table 2).

4.5. Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

The heterogeneity and publication bias of the included studies in this meta-analysis were evaluated. There was a significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000). The publication bias was determined by using Egger's test and the p-value was 0.003. Egger's test was statistically significant and the funnel plot showed the asymmetrical distribution of the included articles. Both of them suggest that there was publication bias (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot with 95% confidence limits of the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

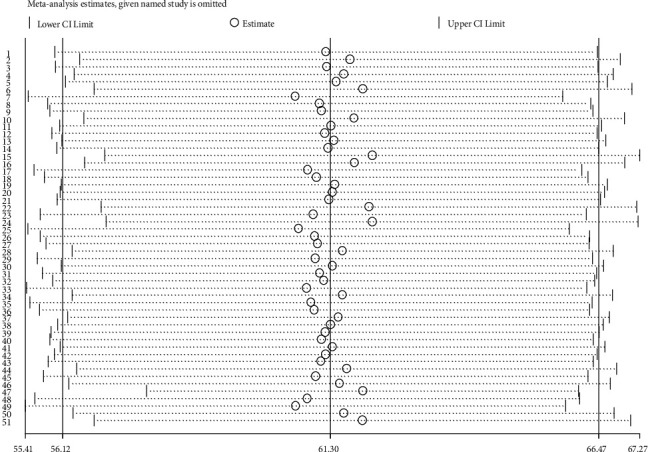

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis

Using the random effects model, the results of a sensitivity analysis revealed that no single study influenced the overall prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The results of sensitivity analysis of 51 studies conducted on pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

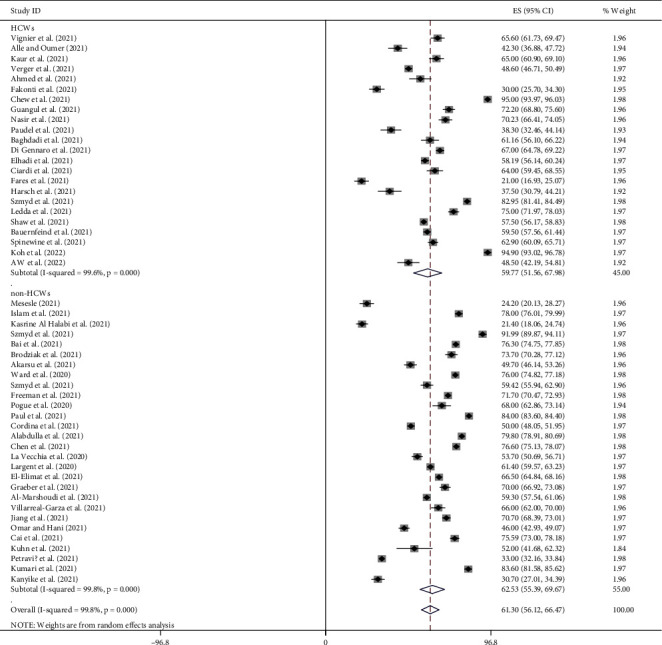

4.7. Pro-Vaccination Attitude towards COVID-19 Vaccine

Random effect model was used in this meta-analysis to estimate the global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs. It was found to be 61.30% (95%CI: 56.12, 66.47). The level of heterogeneity was I2 = 99.8%: p=0.000 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

4.8. Subgroup Analysis

Due to the presence of a significant level of heterogeneity among the included studies, subgroup analysis was needed to identify the sources of heterogeneity. Therefore, subgroup analysis was done by using study participants, publication year, and sample size to determine the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

4.9. Subgroup Analysis through the Study Participants

The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine was 59.77% (95%CI [51.56, 67.98]; I2 = 99.6%, p=0.000) among HCWs participants, and 62.53% (95%CI [55.39, 69.67]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) among non-HCWs participants (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis through study participants on the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

4.10. Subgroup Analysis by Sample Size

The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 54.31% (95%CI [43, 65.63]; I2 = 99.5%, p=0.000) for sample size <700 and 66.49% (95%CI [60.01, 72.98]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for sample size >700 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis by sample size on the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

4.11. Subgroup Analysis by Year of Publication

The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 60.70% (95%CI [54.08, 67.44]; I2 = 93.0%, p=0.000) for studies published in 2020 year and 61.31% (95%CI [55.93, 66.70]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for the studies published after 2020 years (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis by year of publication on the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally.

5. Discussion

Despite the fact that more than a year has passed since the WHO stated a COVID-19 pandemic, there is no effective treatment yet. The only strategy to halt the virus from spreading is the vaccination of the population as per the recent evidence. However, more populations should be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. This is a substantial contest for healthcare systems. Having an effective vaccine is not equivalent to using it, public acceptance is crucial [97]. Besides, despite the consideration of vaccination good achievements of the twentieth century, there are remaining public health issues including insufficient, delayed, and unstable vaccination uptake [98]. Generally, the willingness to take the vaccine against COVID-19 will be the next main phase in fighting this pandemic. However, achieving high uptake will be a challenge and may be impeded by online misinformation and attaining significant uptake will be a contest [99].

Hence, this systematic review was intended to determine the pro-vaccination attitude and associated factors towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs globally. Recognizing the level of attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine and its associated factors among concerning these two major populations would have a substantial role in managing and controlling this pandemic. This is due to the fact that this study provides critical evidences at the time of this global crisis, which is because of the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is supported by the study which explains that knowing the public needs and factors determining their attitude towards vaccines would assist to plan for multilevel interventions depending on the evidence to improve vaccine uptake globally [100]. Generally, to predict and be ready for the future epidemic and pandemic reply, it would be crucial to understand how populations approach emerging infectious diseases [101].

This systematic review and meta-analysis were done by using comprehensive search strategies. It was done based on PRISMA 2020 guidelines and checklists. The quality of the included studies was determined by using the modified NOS assessment. All included studies were cross-sectional. Publication bias was assessed by using Egger's test and funnel plots.

This meta-analysis revealed that the global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 61.30% (95%CI: 56.12, 66.47, I2 = 99.8%: p=0.000). Due to the presence of a significant level of heterogeneity among the included studies, subgroup analysis was needed to identify the sources of heterogeneity. Therefore, subgroup analysis was done by using study participants, publication year, and sample size to determine the pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs globally. The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine was 59.77% (95%CI [51.56, 67.98]; I2 = 99.6%, p=0.000) among HCWs participants, and 62.53% (95%CI [55.39, 69.67]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) among non-HCWs participants. The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 54.31% (95%CI [43, 65.63]; I2 = 99.5%, p=0.000) for sample size <700 and 66.49% (95%CI [60.01, 72.98]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for sample size >700. The global pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was 60.70% (95%CI [54.08, 67.44]; I2 = 93.0%, p=0.000) for studies published in 2020 year and 61.31% (95%CI [55.93, 66.70]; I2 = 99.8%, p=0.000) for the studies published after 2020 years.

The results of this systematic review showed that there was a substantial discrepancy on the level of attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs globally. The level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs ranged from 21% [60] to 95% [52]. This finding demonstrates that there is a crucial problem that needs to be addressed on high priority to cease the era of the current pandemic. This is due to the fact that HCWs are at a high risk of COVID-19 [40]. This infection in HCWs would have an instant consequence on their occupation and the entire healthcare system [39]. Evidences revealed that greater than 50% of the global population have not been vaccinated. The vaccine coverage is less than 20% in some low- and middle-income countries [102]. The study conducted on acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination at different hypothetical efficacy and safety levels in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America revealed a higher possibility of side effects caused a large drop in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate at the same efficacy level. This showed the importance of accurate communication regarding vaccine safety and efficacy on attitude towards the vaccine and intentions to get vaccinated [103].

Factors associated with attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs were age [47, 49, 50, 56, 57, 59], gender [50, 56, 59], race [59], work experience [56], home location [59], having no fear of injections [56], being a non-smoker [56], profession [47, 57], presence of chronic illnesses [50], allergy [50], confidence in pharmaceutical companies [46], confidence in the management of the epidemic [46], history of taking influenza vaccine [49], vaccine recommendation [49, 51], perceived risk of new vaccines [49], perceived utility of vaccine [49], receiving a seasonal flu vaccination in the last 5 years [51], working in a private hospital [51], a high perceived pandemic risk index [52], low vaccine harm index [52], high pro-socialness index [52], using Facebook as main information source about antiSARS-CoV-2 vaccination [57], being in close contact with a high-risk group [57], having undertaken seasonal flu vaccine during the 2019–2020 season [57], role within the hospital [59], knowledge about the virus [59], confidence in and expectations about personal protective equipment, and behaviors [59].

Concerning to non-HCWs, the level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs was ranged from 21.4% [69] to 91.99% [70]. Factors associated with attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs were age [65, 66, 74, 75, 86, 89], gender [65, 68, 69, 74, 75, 78, 85, 88], educational level [65, 88], occupation [65, 85], marital status [69, 88], residency [71, 88], income [74, 75], ethnicity [75], risk for severe course of COVID-19 [65], direct contact with COVID-19 at work [65], being a health profession [66, 78], being vaccinated against seasonal flu [65, 66, 88], perceived benefits [66], cues to actions [66], having previous history vaccination [68], fear of passing on the disease to relatives [70], and the year of medical study [70], studying health-related courses [71], COVID-19 concern [74], adherence level to social distancing guidelines [75], history of chronic disease [85], being pregnant [85], perceived vaccine safety [89], having a close acquaintance who did not experience a vaccine-related adverse reaction [86], having more information about vaccine effectiveness [86], mandatory vaccination [86], being recommended to be vaccinated [86], lack of the confidence in the healthcare system to control epidemic [88], heard about COVID-19 vaccines [89], believe in COVID-19 vaccines protection from COVID-19 infection [89], those who encouraged their family members and friends to get vaccinated [89].

Generally, the findings of this systematic review showed that several factors have been associated with the attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs. This is because of the fact that even though the immunization coverage is stated administratively across the world, no likewise vigorous monitoring system occurs for vaccine confidence. There is rising evidence of vaccine denial because of the lack of trust in the benefits, safety, and effectiveness of vaccines [104]. The acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine was vastly affected by the effectiveness of the vaccine [105]. Besides, if people lack enough knowledge towards the vaccine, this might lead to a negative attitude about it, which will avoid it to accept the vaccine. If communication efforts fail to address vaccine-negative persons', liberty-associated concerns may not be successful [106]. Even, the political talk was found to have a significant effect on the attitude of individuals. For instance, this study showed that political talk plays a considerable role in shaping and polarizing attitude on stem cell research [107]. The intention to accept this vaccine maybe affected by online misinformation, which is significantly associated with failure in vaccination intent [99]. Furthermore, vaccine-related conspiracy theories could affect the attitude of individuals towards the vaccine. This is supported by the experimental study conducted in China [108]. Moreover, according to the planned behavior theory, attitude regarding to behavior, subjective norms of behavior, and perceived control over behavior forecast behavioral willingness, while this willingness together with perceived behavioral control accounts for a substantial proportion of variance in behavior [109].

5.1. Limitations of the Study

It was difficult to consider some of the articles conducted on pro-vaccination attitude and associated factors towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs and non-HCWs, because they had not clearly measured the outcome variables. Moreover, some of those studies did not address factors associated with pro-vaccination attitude.

5.2. Recommendations

The acceptance of vaccines against COVID-19 is vital to fight this pandemic [110]. Hence, to rise the vaccination, considering the psychological science of action is suggested. It can be applied through: thoughts and feelings, social processes, and interventions, which can facilitate vaccination [98]. In the theory of normative conduct, norms have a substantial role in shaping human behavior. Thus, improving the probability of socially beneficial behavior in others via norm activation would be well advised [111]. Vaccination against COVID-19 pandemic might be a significant element of public health and fighting anti-vaccination attitude may assist this effort [112]. Preventing the attack on science, trust in scientists, and using nonconservative media for the better perception of COVID-19 vaccine is advised. The use of nonconservative media would rise the trust in scientists, whereas this would rise the certainty that COVID-19 vaccine could be a good solution for this pandemic. This is supported by the study conducted in the United States of America [113]. Considering the power and impact of media usage on social trust and risk perception, more efforts are required to confirm a correct and balanced information is being spread, while the social media in particular [114]. Social norms and family discussion might be fundamental in qualifying the community for the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine. This is supported by the study done among Asian-Americans in the United States of America [115]. The coupled monitoring vaccine attitude and vaccination rates at the nationwide and subnational levels could support in identifying individuals with diminishing confidence and acceptance towards the vaccine [116]. Applying the protection motivation theory is also suggested for this pandemic. This is because, in the context of this theory, the individuals under threat made their protection decisions and coping judgements. According to the protection motivation theory, individuals under threat base their protection decisions on threat and coping appraisals. In the case of preventable communicable diseases, the theory holds that motivation for vaccination will be higher the more alarming a person's threat appraisals and the more promising her coping appraisals are [117]. Lastly, since rumors and conspiracy theories may bring mistrust which contributes to vaccine hesitancy, following the misinformation regarding a COVID-19 vaccine in real-time and using social media to distribute accurate information can support to protect the population from misinformation [118]. The campaigns and messaging concerning to take the vaccine against COVID-19 should consider the risk of COVID-19 to others and the requirement for everybody to take the vaccine [119]. Evolving communication to avoid vaccine hesitancy is significant to control COVID-19. Forwarding the effective messages to the public concerning this vaccine is crucial to promote the acceptance of this vaccine [120]. Campaigns to disseminate information are also vital to promote participation in the immunization of COVID-19 pandemic [121].

6. Conclusions

Despite the substantial crisis made by COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, it has not been managed and controlled effectively. The vaccines against COVID-19 have been developed, after a long wait and worldwide anxiety, as the best solution for this pandemic. The acceptance of vaccines against COVID-19 is vital to fight this pandemic. This meta-analysis revealed that the global estimated pooled prevalence of pro-vaccination attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs was unsatisfactory. Whereas, according to this systematic review finding, the level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs ranged from 21% to 95%. Age, gender, race, work experience, home location, having no fear of injections, being a non-smoker, presence of chronic illnesses, profession, allergies, confidence in pharmaceutical companies, confidence in the management of the epidemic, history of taking influenza vaccine, vaccine recommendation, perceived risk of new vaccines, perceived utility of vaccine, receiving a seasonal flu vaccination in the last 5 years, working in a private hospital, a high perceived pandemic risk index, low vaccine harm index, high pro-socialness index, using Facebook as main information source about antiSARS-CoV-2 vaccination, being in close contact with a high-risk group, having undertaken seasonal flu vaccine during the 2019–2020 season, role within the hospital, knowledge about the virus, confidence in and expectations about personal protective equipment, and behaviors were factors significantly associated with the attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among HCWs.

The level of positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs ranged from 21.4% to 91.99%. Factors associated with attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine among non-HCWs were age, gender, educational level, occupation, marital status, residency, income, ethnicity, risk for severe course of COVID-19, direct contact with COVID-19 at work, being a health profession, being vaccinated against seasonal flu, perceived benefits, cues to actions, having previous history of vaccination, fear of passing on the disease to relatives, and the year of medical study, studying health-related courses, COVID-19 concern, adherence level to social distancing guidelines, history of chronic disease, being pregnant, perceived vaccine safety, having a close acquaintance who did not experience a vaccine-related adverse reaction, having more information about vaccine effectiveness, mandatory vaccination, being recommended to be vaccinated, lack of the confidence in the healthcare system to control epidemic, heard about COVID-19 vaccines, believe in COVID-19 vaccines protection from COVID-19 infection, those who encouraged their family members and friends to get vaccinated.

The unfavorable attitude regarding COVID-19 vaccine among both HCWs and non-HCWs would significantly reduce the role of vaccination in dropping the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the community. Globally, there is a need for a call for action to cease the time and the associated crisis of this pandemic. This is because HCWs are the major source of health-related information for their communities. Thus, we need to equip them with the most truthful and reliable knowledge to improve their attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

Coronavirus disease 2019

- HCWs:

Healthcare workers

- non-HCWs:

Nonhealthcare worker

- PRISMA:

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- US:

the United States

- NOS:

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Disclosure

Since this is a systematic review and meta-analysis, there was no data collected from the people. Besides, this manuscript is posted as a preprint on Research Square [122].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest for this work.

Authors' Contributions

The author has contributed to the conception of the study, drafting or revising the article, writing the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary 1 file: Methodological quality assessment of cross-sectional studies using modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Supplementary 2 file: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

References

- 1.The impact of covid-19 on children in west and central Africa: learning from 2020; save the children. resource centre. 2021. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/18647/pdf/rapport_covid_anglais.pdf .

- 2.Mannan K. A., Farhana K. M. Knowledge, attitude and acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: a global cross-sectional study. SSRN Electronic Journal . 2020;6 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3763373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lotfi M., Hamblin M. R., Rezaei N. COVID-19: transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clinica Chimica Acta . 2020;508:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Y., Yang H., Ji W., et al. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of COVID-19. Viruses . 2020;12(4):p. 372. doi: 10.3390/v12040372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Wang Y., Ye D., Liu Q. Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents . 2020;55(6) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948.105948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA . 2020;323(21):p. 2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dariya B., Nagaraju G. P. Understanding novel COVID-19: its impact on organ failure and risk assessment for diabetic and cancer patients. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews . 2020;53:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Q., Shi Y. Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) and neonate: what neonatologist need to know. Journal of Medical Virology . 2020;92(6):564–567. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ataguba J. E. COVID-19 pandemic, a war to be won: understanding its economic implications for Africa. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy . 2020;18(3):325–328. doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadermann A. C., Thomson K. C., Richardson C. G., et al. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open . 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871.e042871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kajdy A., Feduniw S., Ajdacka U., et al. Risk factors for anxiety and depression among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2020;99(30) doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000021279.e21279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang L., Ren H., Cao R., et al. The effect of covid-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly . 2020;91 doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshikawa H., Wuermli A. J., Britto P. R., et al. Effects of the global coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic on early childhood development: short- and long-term risks and mitigating program and policy actions. The Journal of Pediatrics . 2020;223:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahriani M., Anwar S., Yufika A., et al. Disruption of childhood vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Narrative Journal . 2021;1 doi: 10.52225/narraj.v1i1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deprest J., Choolani M., Chervenak F., et al. Fetal diagnosis and therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance on behalf of the international fetal medicine and surgery society. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy . 2020;47(9):689–698. doi: 10.1159/000508254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachega J. B., Kapata N., Sam-Agudu N. A., et al. Minimizing the impact of the triple burden of COVID-19, tuberculosis and HIV on health services in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2021;113(Suppl 1):S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogunbiyi O. The disproportionate burden of COVID-19 in Africa. COVID-19 Pandemic . 2022;2022:179–187. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-323-82860-4.00021-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dashraath P., Wong J. L. J., Lim M. X. K., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology . 2020;222(6):521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borriello A., Master D., Pellegrini A., Rose J. M. Preferences for a COVID-19 vaccine in Australia. Vaccine . 2021;39(3):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aw J., Seng J. J. B., Seah S. S. Y., Low L. L. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—a scoping review of literature in high-income countries. Vaccines . 2021;9(8):p. 900. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarus J. V., Ratzan S. C., Palayew A., et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine . 2021;27(2):225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hursh S. R., Strickland J. C., Schwartz L. P., Reed D. D. Quantifying the impact of public perceptions on vaccine acceptance using behavioral economics. Frontiers in Public Health . 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.608852.608852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alley S. J., Stanton R., Browne M., et al. As the pandemic progresses, how does willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 evolve? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2021;18(2):p. 797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palamenghi L., Barello S., Boccia S., Graffigna G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: the forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. European Journal of Epidemiology . 2020;35:785–788. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daly M., Robinson E. Willingness to Vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US: Longitudinal Evidence from a Nationally Representative Sample of Adults from April–October 2020 . New Haven, CT, USA: medRxiv; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graffigna G., Palamenghi L., Boccia S., Barello S. Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine in Italy: a mediation analysis. Vaccines . 2020;8(4):p. 576. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell S., Clarke R., Mounier-Jack S., Walker J. L., Paterson P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine . 2020;38(49):7789–7798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldman R. D., Yan T. D., Seiler M., et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: cross sectional survey. Vaccine . 2020;38(48):7668–7673. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman R. D., Staubli G., Cotanda C. P., et al. Factors associated with parents’ willingness to enroll their children in trials for COVID-19 vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics . 2021;17(6):1607–1611. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1834325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcec R., Majta M., Likic R. Will vaccination refusal prolong the war on SARS-CoV-2? Postgraduate Medical Journal . 2021;97(1145):143–149. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao S., Tam C. C., Li X. Risk exposures, risk perceptions, negative attitudes toward general vaccination, and covid-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in south carolina. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) . 2020;2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.26.20239483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann-Böhme S., Varghese N. E., Sabat I., et al. Once we have it, will we use it? a European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The European Journal of Health Economics . 2020;21(7):977–982. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuppalli K., Brett-Major D. M., Smith T. C. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: we need to start now. Open Forum Infectious Diseases . 2021;8(2) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa658.ofaa658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Küçükkarapınar M., Karadag F., Budakoğlu I., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its relationship with illness risk perceptions, affect, worry, and public trust: an online serial cross-sectional survey from Turkey. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology . 2021;31(1):98–109. doi: 10.5152/pcp.2021.21017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngoyi J. M., Mbuyu L. K., Kibwe D. N., et al. Covid-19 vaccination acceptance among students of the higher institute of medical techniques of lubumbashi, democratic republic of Congo. Rev L’Infirmier Congo . 2020;4:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maroudy D. Vaccination of healthcare workers against COVID-19. Soins . 2021;66(855):10–13. doi: 10.1016/s0038-0814(21)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pean De Ponfilly G., Pilmis B., El Kaibi I., Castreau N., Laplanche S., Le Monnier A. Is the second dose of vaccination useful in previously SARS-CoV-2-infected healthcare workers? Infectious Disease News . 2021;51(21):424–433. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez J., Patón M., Acuña J. M. COVID-19 vaccination rate and protection attitudes can determine the best prioritisation strategy to reduce fatalities. medRxiv . 2021;2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.12.20211094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amit S., Beni S. A., Biber A., Grinberg A., Leshem E., Regev-Yochay G. Postvaccination COVID-19 among healthcare workers, Israel. Emerging Infectious Diseases . 2021;27(4):1220–1222. doi: 10.3201/eid2704.210016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamacooko O., Kitonsa J., Bahemuka U. M., et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2021;18(13):p. 7004. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18137004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thaker J. Planning for a covid-19 vaccination campaign: the role of social norms, trust, knowledge, and vaccine attitudes. 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/q8mz6/

- 42.Mateo-Urdiales A., Del Manso M., Andrianou X., Spuri M., D’Ancona F., Filia A. Initial impact of SARS-Cov-2 vaccination on healthcare workers in italy-update on the 28th of march 2021. Vaccine . 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modesti P. A., Reboldi G., Cappuccio F. P., et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One . 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601.e0147601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells G. A., Shea B., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses . Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yazew K. G., Walle T. A., Azagew A. W. Prevalence of anti-diabetic medication adherence and determinant factors in Ethiopia: a systemic review and meta-analysis, 2019. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences . 2019;11 doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2019.100167.100167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vignier N., Brureau K., Granier S., et al. Attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to get vaccinated among healthcare workers in French guiana: the influence of geographical origin. Vaccines . 2021;9(6):p. 682. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alle Y. F., Oumer K. E. Attitude and associated factors of covid-19 vaccine acceptance among health professionals in debre tabor comprehensive specialized hospital. VirusDisease . 2021;32 doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur A., Kaur G., Kashyap A., et al. Attitude and acceptance of Covid-19 vaccine amongst medical and dental fraternity - a questionnaire survey. Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny . 2021;72(2):185–191. doi: 10.32394/rpzh.2021.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., et al. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Euro Surveillance . 2021;26(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es.2021.26.3.2002047.2002047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmed G., Almoosa Z., Mohamed D., et al. Healthcare provider attitudes toward the newly developed COVID-19 vaccine: cross-sectional study. Nursing Reports . 2021;11(1):187–194. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fakonti G., Kyprianidou M., Toumbis G., Giannakou K. Attitudes and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among nurses and midwives in Cyprus: a cross-sectional survey. Frontiers in Public Health . 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.656138.656138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chew N. W. S., Cheong C., Kong G., et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. International Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2021;106:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bereket A. G., Georgiana G., Mensur O., et al. Healthcare workers attitude towards SARS-COVID-2 Vaccine, Ethiopia. Global Journal of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Research . 2021;7:043–048. doi: 10.17352/2455-5363.000045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nasir M., Perveen R. A., Saha S. K., et al. Vaccination against COVID-19 in Bangladesh: perception and attitude of healthcare workers in COVID-dedicated hospitals. Mymensingh Medical Journal: Maryland Medical Journal . 2021;30(3):808–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paudel S., Palaian S., Shankar P. R., Subedi N. Risk perception and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers and staff at a medical college in Nepal. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy . 2021;14:2253–2261. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.s310289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baghdadi L. R., Alghaihb S. G., Abuhaimed A. A., Alkelabi D. M., Alqahtani R. S. Healthcare workers’ perspectives on the upcoming COVID-19 vaccine in terms of their exposure to the influenza vaccine in riyadh, Saudi arabia: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines . 2021;9(5):p. 465. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Gennaro F., Murri R., Segala F. V., et al. Attitudes towards anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination among healthcare workers: results from a national survey in Italy. Viruses . 2021;13(3):p. 371. doi: 10.3390/v13030371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elhadi M., Alsoufi A., Alhadi A., et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:955–1021. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciardi F., Menon V., Jensen J. L., et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers of an inner-city hospital in New York. Vaccines . 2021;9(5):p. 516. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fares S., Elmnyer M. M., Mohamed S. S., Elsayed R. COVID-19 vaccination perception and attitude among healthcare workers in Egypt. Primary Care & Community Health . 2021;12 doi: 10.1177/21501327211013303.215013272110133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harsch I. A., Ortloff A., Reinhöfer M., Epstude J. Symptoms, antibody levels and vaccination attitude after asymptomatic to moderate COVID-19 infection in 200 healthcare workers. GMS Hyg Infect Control . 2021;16:p. Doc15. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szmyd B., Karuga F. F., Bartoszek A., et al. Attitude and behaviors towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study from Poland. Vaccines . 2021;9(3):p. 218. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ledda C., Costantino C., Cuccia M., Maltezou H. C., Rapisarda V. Attitudes of healthcare personnel towards vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2021;18(5):p. 2703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw J., Stewart T., Anderson K. B., Hanley S., Thomas S. J., Salmon D. A. Assessment of U.S. health care personnel (HCP) attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination in a large university health care system. Infectious Diseases Society of America . 2021;6 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab054.ciab054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bauernfeind S., Hitzenbichler F., Huppertz G., et al. Brief report: attitudes towards covid-19 vaccination among hospital employees in a tertiary care university hospital in germany in December 2020. Infection . 2021;49 doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spinewine A., Pétein C., Evrard P., et al. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination among hospital staff-understanding what matters to hesitant people. Vaccines . 2021;9(5):p. 469. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mesesle M. Awareness and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors in Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Infection and Drug Resistance . 2021;14:2193–2199. doi: 10.2147/idr.s316461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Islam M. S., Siddique A. B., Akter R., et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccinations: a cross-sectional community survey in Bangladesh. medRxiv . 2021 doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kasrine Al Halabi C., Obeid S., Sacre H., et al. Attitudes of Lebanese adults regarding COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Public Health . 2021;21(1):p. 998. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10902-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szmyd B., Bartoszek A., Karuga F. F., Staniecka K., Błaszczyk M., Radek M. Medical students and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: attitude and behaviors. Vaccines . 2021;9(2):p. 128. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bai W., Cai H., Liu S., et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Chinese college students. International Journal of Biological Sciences . 2021;17(6):1469–1475. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.58835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brodziak A., Sigorski D., Osmola M., et al. Attitudes of patients with cancer towards vaccinations-results of online survey with special focus on the vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines . 2021;9(5):p. 411. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Akarsu B., Canbay Özdemir D., Ayhan Baser D., Aksoy H., Fidancı İ, Cankurtaran M. While studies on COVID-19 vaccine is ongoing, the public’s thoughts and attitudes to the future COVID-19 vaccine. International Journal of Clinical Practice . 2021;75(4) doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13891.e13891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ward J. K., Alleaume C., Peretti-Watel P., et al. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: the politicization of a public health issue. Social Science & Medicine . 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414.113414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Freeman D., Loe B. S., Chadwick A., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychological Medicine . 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pogue K., Jensen J. L., Stancil C. K., et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines . 2020;8(4):p. 582. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paul E., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe . 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012.100012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cordina M., Lauri M. A., Lauri J., Cordina M., Lauri M. A., Lauri J. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharmacy Practice . 2021;19(1):p. 2317. doi: 10.18549/pharmpract.2021.1.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alabdulla M., Reagu S. M., Al-Khal A., Elzain M., Jones R. M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: a national cross-sectional survey of a migrant-majority population. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses . 2021;15(3):361–370. doi: 10.1111/irv.12847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen M., Li Y., Chen J., et al. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics . 2021;17(7):2279–2288. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1853449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.La Vecchia C., Negri E., Alicandro G., Scarpino V. Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy and differences across occupational groups, September 2020. Medicina del Lavoro . 2020;111(6):445–448. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v111i6.10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Largent E. A., Persad G., Sangenito S., Glickman A., Boyle C., Emanuel E. J. US public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine mandates. JAMA Network Open . 2020;3(12) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33324.e2033324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.El-Elimat T., AbuAlSamen M. M., Almomani B. A., Al-Sawalha N. A., Alali F. Q. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS One . 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250555.e0250555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Graeber D., Schmidt-Petri C., Schröder C. Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: evidence from Germany. PLoS One . 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248372.e0248372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al-Marshoudi S., Al-Balushi H., Al-Wahaibi A., et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (kap) toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Oman: a pre-campaign cross-sectional study. Vaccines . 2021;9(6):p. 602. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Villarreal-Garza C., Vaca-Cartagena B. F., Becerril-Gaitan A., et al. Attitudes and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncology . 2021;7(8):p. 1242. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jiang N., Wei B., Lin H., Wang Y., Chai S., Liu W. Nursing students’ attitudes, knowledge, and willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Nursing education in Practice . 2021;55 doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Omar D. I., Hani B. M. Attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among Egyptian adults. Journal of Infection and Public Health . 2021;14(10):1481–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cai H., Bai W., Liu S., et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Chinese adolescents. Frontiers of Medicine . 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.691079.691079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuhn R., Henwood B., Lawton A., et al. Covid-19 vaccine access and attitudes among people experiencing homelessness from pilot mobile phone survey in Los Angeles, CA. PloS One . 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Petravić L., Arh R., Gabrovec T., et al. Factors affecting attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: an online survey in Slovenia. Vaccines . 2021;9(3):p. 247. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]