Abstract

We aimed to investigate the prevalence of probable depression and anxiety and their correlates during later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries. Longitudinal data (wave 7 in June/July 2021: n=8,032; wave 8 in September 2021: n=8,250; wave 9 in December 2021/January 2022: n=8,319) were used from the European COvid Survey – a representative sample of community-dwelling adults from several European countries (Germany, United Kingdom, Denmark, Netherlands, France, Portugal, Italy and Spain). In wave 7 (wave 8; wave 9), 23.8% (22.0%; 24.3%) of all respondents had probable depression and 22.6% (22.1%; 23.7%) had probable anxiety. These prevalence rates substantially differed between the European countries. Regressions showed that emerging difficulties with the income were associated with both increases in depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. An increase in one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the SARS-CoV-2, the birth of a child and an increase in the Covid-19 stringency index were associated with increases in depressive symptoms. The significance of probable depression and anxiety during later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries was highlighted. Avoiding income difficulties may also contribute to mental health.

Keywords: Depression, Anxiety, COVID-19, Longitudinal, Representative, Mental health, Corona, SARS-CoV-2, Europe, Income, Stringency Index

1. Introduction

Various countries have reported high prevalence rates of depression and anxiety in recent decades Alonso et al., 2004. The current Covid-19 pandemic confronts individuals with several challenges for their mental well-being including financial hardship (e.g., with a particular high risk for certain professional groups such as the event industry) and social distancing. A recent meta-analysis showed a prevalence of anxiety of 38.1% (depression: 34.3%) among general populations in different countries during the pandemic Necho et al., 2021. However, thus far, most of the existing studies examined the prevalence during earlier stages of the pandemic and only in one specific country (as an overview: Necho et al., 2021). Only some studies compared two countries. For example, one study compared representative data from the United Kingdom and Austria Budimir et al., 2021 and another study compared representative data from the United States and Australia Czeisler et al., 2021.

Additionally, there is limited knowledge using data from representative longitudinal studies in times of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Daly and Robinson, 2021; Hyland et al., 2021; Gilbar et al., 2022. Consequently, the purpose of our current study was to show data on the prevalence of probable depression and anxiety and to identify the correlates in eight European countries during later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., June 2021 to January 2022)) longitudinally. For this purpose, longitudinal data from the European COvid Survey (ECOS) covering Germany, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Portugal, Italy and Spain were used. Knowledge of the factors that were linked to probable depression and anxiety over time during the COVID-19 pandemic may aid health professionals in identifying people at risk for these mental illnesses. Moreover, such knowledge may help to mitigate the projected rise in mental illnesses (Riedel-Heller and Richter, 2020).

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

Longitudinal data were collected from the European COvid Survey (ECOS) (wave 7 in June/July 2021: n=8,032; wave 8 in September 2021: n=8,250; wave 9 in December 2021/January 2022: n=8,319), which included Germany, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Portugal, Italy, and Spain.

Data from a sample of about 1,000 adult individuals was collected in each country by the market research firm Dynata. Several recruiting techniques were used to reach the general population (open recruitment, affiliate networks, mobile apps or loyalty programs). Quotas were used to ensure gender, age, region, and education representation (based on national census data) within each country. Sabat et al. provided additional information Sabat et al., 2020.

Dynata obtained written informed consent from each individual participant. The participants' confidentiality and anonymity were protected. The University of Hamburg in Germany provided ethical approval for this study (clearance approved at 10th July 2020; under the umbrella project "Countering COVID-19: A European survey on the acceptability and commitment to preventive measures"). It was not necessary to obtain ethical approval from all countries because patients were not involved, among other things.

2.2. Dependent variables

The validated Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4, 2-item depression scale, PHQ-2 Kroenke et al., 2003; Löwe et al., 2005 and 2-item anxiety scale, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2)) Kroenke et al., 2007 were used to assess probable depression and anxiety. While the PHQ-2 includes the two DSM-V diagnostic main criteria for depressive disorders Association AP 2013, the GAD-2 includes the two main criteria for GAD Association AP 2013. The GAD-2 has been shown to be a screening tool for post-traumatic stress disorder (specificity: 0.81; sensitivity: 0.59), social anxiety disorder (specificity: 0.81; sensitivity: 0.70), and panic disorder (specificity: 0.81; sensitivity: 0.76) Kroenke et al., 2007. The PHQ-2 can be used to screen for major depressive disorder (specificity: 0.78; sensitivity: 0.87) and any depressive disorder (specificity: 0.86; sensitivity: 0.79) Löwe et al., 2005.

These two measures are combined into a four-item scale by the PHQ-4. As previously recommended [11,10], sum scores of 3 (for both tools, PHQ-2 and GAD-2) were used as cut-off points for probable depression and anxiety, respectively. More information is provided elsewhere Kroenke et al., 2009; Löwe et al., 2010. In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 (GAD-2: 0.87; PHQ-2: 0.83) in wave 7. It was 0.90 (GAD-2: 0.87; PHQ-2: 0.81) in wave 8 and also 0.90 (GAD-2: 0.87; PHQ-2: 0.82) in wave 9. In sum, a good internal consistency was demonstrated. Additionally, for the PHQ-4, McDonald's omega McDonald, 1999 was .91 in wave 7, .90 in wave 8, and .91 in wave 9, respectively Shaw, 2021.

2.3. Independent variables

The following time-varying factors were used in regressions: age, family status (married/registered partnership; living together (relationship); living alone (single); living alone (in a relationship); widowed; other), education (low education; medium education; high education; using the country specific education system; see Varghese et al. Varghese et al., 2021), professional group (health-related sector; education; food retail; research; other), perceived difficulties with income (“Thinking of your household's total monthly income, would you say that your household is able to make ends meet…“: with great difficulty; with some difficulties; fairly easily; easily), having children (absence of a child below 18 years; having one or more children aged below 18 years), infection with the novel coronavirus (no; yes, confirmed; yes, but not yet confirmed; don't know), one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the coronavirus (single item from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk), perceived risk to one's own health from Covid-19 (single item from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk), perceived risk to the health of one's own family members from Covid-19 (single item from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk), perceived risk to the health of people in one's own community from Covid-19 (single item from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk) and the country-specific Oxford Covid-19 stringency index Hale et al., 2021. It consists of 19 indicators focusing on actions and behavioral interventions referring to health system, economic response, closure and containment. In this index, each indicator is scored based on an ordinal score (0 – 2, 3, 4 or 5), resulting in a sum score ranging from 0 to 100 (strictest).

Moreover, for descriptive purposes, the time-constant factors (which means factors that do not vary within individuals over time) sex (men; women) and country (Germany; United Kingdom; Denmark; Netherlands; France; Portugal; Italy; Spain) were used.

2.4. Statistical analysis

First, we showed the prevalence rates for probable depression and anxiety in the total sample and for various subgroups. Subsequently, the longitudinal correlates of depressive symptoms (first outcome measure) and anxiety symptoms (second outcome measure) were estimated using linear fixed effects (FE) regressions. This assists in exploiting within-information (i.e., changes within individuals over time) Cameron and Trivedi, 2005. Contrary to other popular methods such as linear random effects (RE) regressions, such linear FE regressions deliver consistent estimates even when time-constant factors (both, unobserved and observed) are systematically correlated with time-varying regressors (under the assumption of strict exogeneity) Cameron and Trivedi, 2005. This analytical choice was backed up by Sargan-Hansen tests (which corresponds to Hausman-tests with cluster-robust standard errors: Sargan-Hansen statistic was 207.6, p<.001 with depressive symptoms as outcome measure and it was 283.4, p<.001 with anxiety symptoms as outcome measure) Schaffer and Stillman, 2006.

Such linear FE regressions exclusively exploit changes within individuals over time such as intraindividual transitions in depressive symptoms from wave 7 to wave 9. Thus, the estimates only refer to individuals with such intraindividual changes over time. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that this is not a weakness of FE estimates rather it mirrors the fact that only some individuals had these changes over time Cameron and Trivedi, 2005. The significance level was set at =.05. To conduct statistical analysis, Stata 16.1 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of probable depression and anxiety stratified by various characteristics

In Table 1 , prevalence rates of probable depression and probable anxiety are given. In wave 7, (wave 8; wave 9), 23.8% (22.0%; 24.3%) of all respondents had probable depression and 22.6% (22.1%; 23.7%) had probable anxiety. Both probable depression and probable anxiety had 16.8% (15.6%; 17.4%) of the individuals. No consistent trend could be identified regarding the prevalence rates from wave 7 to wave 9.

Table 1.

Prevalence rate for probable depression and probable anxiety stratified by various groups in wave 7 in June/July 2021, wave 8 in September 2021, and wave 9 in December 2021/January 2022 (N and %).

| Wave 7 | Wave 8 | Wave 9 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Presence of probable depression | Presence of probable anxiety | Sample size | Presence of probable depression | Presence of probable anxiety | Sample size | Presence of probable depression | Presence of probable anxiety | |

| Total sample | N=8032 | 23.8% | 22.6% | N=8250 | 22.0% | 22.1% | N=8319 | 24.3% | 23.7% |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | N=3888 | 21.0% | 20.0% | N=3970 | 20.1% | 19.8% | N=3999 | 22.1% | 21.1% |

| Female | N=4144 | 26.4% | 25.0% | N=4280 | 23.7% | 24.3% | N=4320 | 26.4% | 26.0% |

| Country | |||||||||

| Germany | N=1015 | 23.6% | 22.8% | N=1027 | 20.8% | 19.5% | N=1007 | 24.5% | 22.6% |

| United Kingdom | N=1019 | 30.0% | 26.6% | N=1038 | 28.7% | 28.0% | N=1023 | 29.4% | 28.7% |

| Denmark | N=1008 | 28.6% | 22.2% | N=1035 | 24.1% | 20.5% | N=1016 | 27.2% | 22.3% |

| Netherlands | N=1004 | 19.2% | 17.0% | N=1037 | 18.8% | 17.4% | N=1022 | 18.1% | 14.7% |

| France | N=1013 | 19.8% | 21.4% | N=1011 | 21.4% | 19.9% | N=1139 | 23.6% | 23.7% |

| Portugal | N=1001 | 19.7% | 20.9% | N=1045 | 19.0% | 22.5% | N=1036 | 21.2% | 24.3% |

| Italy | N=1013 | 23.2% | 24.5% | N=1039 | 21.1% | 25.5% | N=1057 | 28.2% | 28.3% |

| Spain | N=959 | 26.2% | 25.1% | N=1018 | 21.8% | 23.9% | N=1019 | 22.4% | 24.3% |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 18-29 | N=1311 | 41.2% | 40.3% | N=1363 | 38.3% | 40.2% | N=1228 | 44.6% | 45.6% |

| 30-49 | N=3080 | 28.1% | 27.6% | N=3071 | 25.3% | 26.1% | N=3138 | 28.6% | 27.9% |

| 50-64 | N=2066 | 17.1% | 15.8% | N=2115 | 16.4% | 15.5% | N=2181 | 16.6% | 15.7% |

| 65-74 | N=1441 | 11.0% | 8.4% | N=1431 | 8.8% | 8.7% | N=1473 | 12.2% | 10.7% |

| 75+ | N=243 | 8.3% | 4.5% | N=262 | 13.7% | 9.2% | N=299 | 13.0% | 10.7% |

| Children | |||||||||

| No children aged below 18 | N=5581 | 20.2% | 18.8% | N=5689 | 18.6% | 18.8% | N=5820 | 20.9% | 20.7% |

| Yes, one or more aged below 18 | N=2451 | 31.9% | 31.0% | N=2561 | 29.4% | 29.5% | N=2499 | 32.3% | 30.6% |

| Education | |||||||||

| Low education | N=1348 | 24.0% | 23.0% | N=1296 | 21.6% | 21.1% | N=1232 | 22.2% | 22.1% |

| Middle education | N=3173 | 21.7% | 20.8% | N=3179 | 20.3% | 21.8% | N=3157 | 23.4% | 22.9% |

| High education | N=3511 | 25.6% | 24.0% | N=3775 | 23.5% | 22.8% | N=3930 | 25.7% | 24.8% |

| Professional group | |||||||||

| Health-related sector | N=576 | 30.4% | 30.6% | N=614 | 29.8% | 28.0% | N=640 | 28.8% | 29.1% |

| Education | N=551 | 28.7% | 27.0% | N=543 | 25.8% | 25.6% | N=594 | 29.6% | 27.6% |

| Food retail | N=246 | 30.9% | 28.9% | N=239 | 30.5% | 31.4% | N=216 | 36.6% | 34.3% |

| Research | N=151 | 30.5% | 25.8% | N=137 | 28.5% | 32.1% | N=142 | 32.4% | 35.2% |

| Other | N=6508 | 22.4% | 21.2% | N=6717 | 20.5% | 20.8% | N=6727 | 22.9% | 22.2% |

| Infection with the novel coronavirus | |||||||||

| Yes, confirmed | N=617 | 42.3% | 43.9% | N=737 | 38.5% | 39.2% | N=1021 | 34.9% | 36.1% |

| Yes, but not yet confirmed | N=243 | 35.8% | 35.0% | N=209 | 39.2% | 37.3% | N=220 | 41.4% | 43.6% |

| No | N=6804 | 21.6% | 20.1% | N=6897 | 19.6% | 19.7% | N=6657 | 21.9% | 20.8% |

| Don't know | N=368 | 25.3% | 24.7% | N=407 | 23.6% | 24.6% | N=421 | 27.8% | 27.6% |

| Income | |||||||||

| With great difficulty | N=660 | 41.8% | 45.6% | N=646 | 39.5% | 42.6% | N=640 | 43.6% | 46.4% |

| With some difficulty | N=2783 | 27.9% | 26.4% | N=2861 | 26.7% | 26.3% | N=3024 | 28.6% | 28.9% |

| Fairly easily | N=3374 | 19.7% | 18.1% | N=3458 | 17.0% | 17.9% | N=3449 | 19.9% | 18.4% |

| Easily | N=1215 | 15.9% | 13.6% | N=1285 | 16.1% | 14.1% | N=1206 | 15.9% | 13.6% |

| Vaccination status (Covid-19) | |||||||||

| No | N=1441 | 24.6% | 22.4% | N=931 | 20.8% | 22.1% | N=775 | 23.1% | 19.7% |

| Not yet, but intended to vaccinate | N=1211 | 32.0% | 31.5% | N=284 | 29.2% | 32.4% | N=159 | 30.2% | 33.3% |

| Yes, at least one shot | N=5380 | 21.8% | 20.6% | N=7035 | 21.8% | 21.7% | N=7385 | 24.3% | 23.9% |

Notes: In bivariate (cross-sectional) analysis, probable depression and probable anxiety were significantly associated with all variables listed in each of the three waves, except for the (non-significant) association between educational level and probable anxiety (in wave 8 and 9) and the (non-significant) association between vaccination status and probable depression (wave 9).

Particularly individuals aged 18 to 29 years, individuals being infected with the SARS-CoV-2 and individuals with great income difficulties reported very high prevalence rates for probable depression and probable anxiety in all three waves. Some examples: In wave 7, 41.2% of the individuals aged 18 to 29 years had probable depression (probable anxiety: 40.3%), 42.3% of individuals with a confirmed infection with the novel coronavirus had probable depression (probable anxiety: 43.9%) and 41.8% of the individuals with great income difficulties had probable depression (probable anxiety: 45.6%). Bivariate (cross-sectional) analysis revealed that both outcome measures were associated with nearly all independent variables. Further details are shown in Table 1.

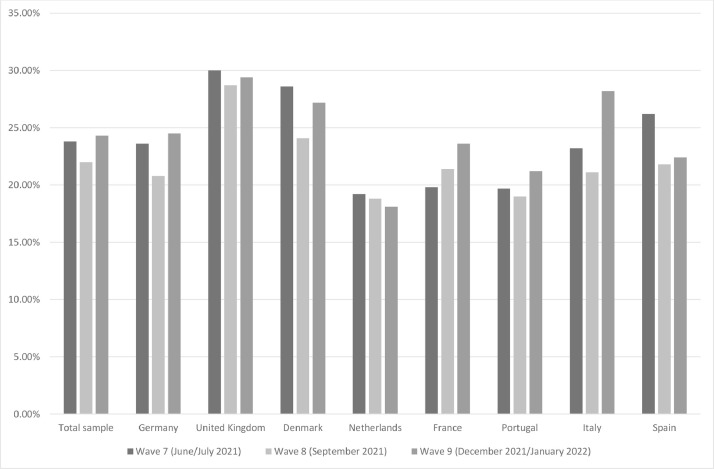

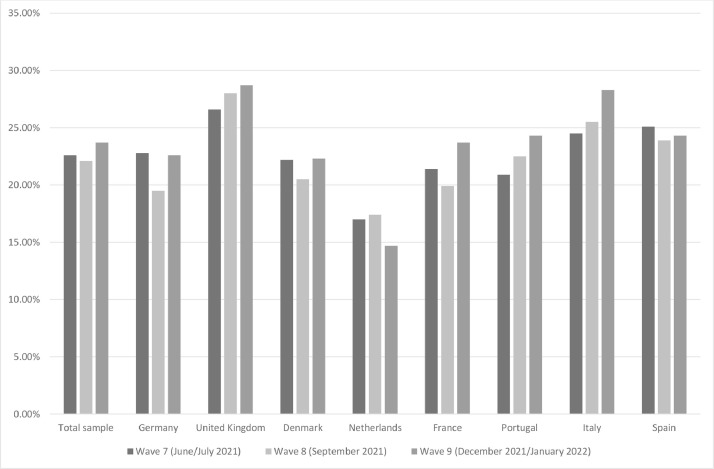

In Fig. 1 (probable depression) and Fig. 2 (probable anxiety), we displayed the prevalence rates in the eight European countries from wave 7 to wave 9. In most of these countries, the prevalence rates for both probable depression and probable anxiety decreased from wave 7 to wave 8 and increased from wave 8 to wave 9.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of probable depression among European countries from June/July 2021 to December 2021/January 2022.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of probable anxiety among European countries from June/July 2021 to December 2021/January 2022.

3.2. Longitudinal regression analysis

Results of linear FE regressions are depicted in Table 2 . These regressions showed that an increase in depressive symptoms was associated with changes from ‘easily’ to ‘some’ (β=.20, p<.01) or ‘great’ income difficulties (β=.21, p<.05), an increase in one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the coronavirus (β=.04, p<.05), a change from no child below 18 years to at least one child below 18 years (β=.19, p<.05) and an increase in the Covid-19 stringency index (β=.003, p<.001).

Table 2.

Determinants of depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. Results of linear FE regressions (ECOS; wave 7 to wave 9).

| Independent variables | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Marital status: - Living together (relationship) (Ref.: - married / registered partnership) | -0.00 | 0.05 |

| (0.09) | (0.09) | |

| - Living alone (single) | 0.07 | -0.08 |

| (0.13) | (0.14) | |

| - Living alone (in a relationship) | -0.09 | -0.15 |

| (0.13) | (0.14) | |

| - Widowed | -0.03 | -0.14 |

| (0.22) | (0.21) | |

| - Other | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| (0.14) | (0.14) | |

| Children: Having one or more children aged below 18 years (Ref.: Absence of a child aged below 18 years) | 0.19* | -0.00 |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Education: - Middle (Ref.: low education) | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| (0.07) | (0.07) | |

| - High | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | |

| Professional group: - Education (Ref.: Health-related sector) | -0.06 | -0.06 |

| (0.13) | (0.12) | |

| - Food retail | -0.02 | 0.11 |

| (0.16) | (0.16) | |

| - Research | -0.11 | 0.00 |

| (0.18) | (0.17) | |

| - Other | -0.12 | -0.02 |

| (0.10) | (0.09) | |

| Own risk of getting infected with the coronavirus (from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk) | 0.04* | 0.04+ |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Risk to one's own health from Covid-19 (from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk) | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Risk to the health of one's own family members from Covid-19 (from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk) | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Risk to the health of people in one's own community from Covid-19 (from 1 = no risk at all to 5 = very high risk) | -0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Income (ability to make ends meet): - With great difficulty (Ref.: easily) | 0.21* | 0.24* |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | |

| - With some difficulty | 0.20** | 0.14* |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| - Fairly easily | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | |

| Infection with the novel coronavirus: - Yes, confirmed (Ref.: no) | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | |

| - Yes, but not yet confirmed | 0.10 | -0.08 |

| (0.10) | (0.11) | |

| - Don't know | -0.02 | -0.04 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Covid-19 Stringency Index (from 0 to 100, with 100 = strictest)) | 0.003*** | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Covid-19 vaccination: - Intention to vaccinate against Covid-19 (Ref.: not vaccinated against Covid-19) | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| (0.07) | (0.07) | |

| - At least one vaccination against Covid-19 | -0.03 | 0.08 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Observations | 15,410 | 15,410 |

| Number of Individuals | 6,153 | 6,153 |

| Pseudo R² | 0.008 | 0.005 |

Comments: Unstandardized beta-coefficients are reported; 95% confidence intervals in parentheses; *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, + p<0.10

Additionally, an increase in anxiety symptoms was associated with changes from ‘easily’ to ‘some’ (β=.14, p<.05) or ‘great’ income difficulties (β=.24, p<.05), whereas it was not associated with any of the other time-varying independent variables.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The main goal of this study, which used longitudinal data from the ECOS, was to investigate the prevalence of probable depression and probable anxiety and their correlates - in eight European countries during later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study revealed the extent of probable depression and anxiety in June/July 2021, September 2021 and December 2021/January 2022 - with some notable differences between these European countries. Particularly, individuals in specific countries such as the United Kingdom, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, individuals with an infection with the SARS-CoV-2 and individuals with great income difficulties had high prevalence rates for probable depression and probable anxiety in all of these waves. Linear FE regressions revealed that emerging difficulties with the income are associated with both increases in depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, an increase in one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the coronavirus, the birth of a child and an increase in the Covid-19 stringency index were also associated with increases in depressive symptoms.

4.2. Previous research and possible explanations

Our study showed that probable depression and anxiety are quite common in the general adult population in eight European countries from Mid-2021 to early 2022. In comparison to the pre-pandemic era (e.g., Alonso et al., 2004), the prevalence rates identified in our study were considerably higher. For example, based on data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (covering six European countries; data collection from 2001 to 2003), Alonso et al. Alonso et al., 2004 showed that 3.9% of the individuals reported a major depressive disorder in the past 12 months (lifetime prevalence: 12.8%) and 1.0% of the individuals reported a generalized anxiety disorder in the past 12 months (lifetime prevalence: 2.8%). Another example: Based on data from the German health interview and examination survey for adults (data collection from 2008 to 2011), Jacobi et al. Jacobi et al., 2014 reported that 6.0% of the individuals had a major depressive disorder in the preceding 12 months and 2.2% of the individuals had a generalized anxiety disorder in the preceding 12 months among the general adult population in Germany (aged 18 to 79 years).

Such increase (prior compared to during the pandemic) is often explained by social distancing, income difficulties and concerns about one's own health as well as the health of others Hajek et al., 2022. It should be noted that higher prevalence rates during the pandemic were already reported by various other studies (e.g., Hajek et al., 2022; MacDonald et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022 and were thus in accordance with our expectations. Nevertheless, our study adds to our current knowledge by using (i) representative and (ii) longitudinal data from (iii) various European countries collected during (iv) later stages of the pandemic.

With regard to the prevalence rates of probable depression and anxiety, quite large cross-country differences were identified, for instance, when comparing the United Kingdom with the Netherlands. Such notable discrepancies were also identified prior to the pandemic (e.g., Alonso et al., 2004) and are frequently explained by cultural differences Simon et al., 2002. Differences in locus of control Steptoe et al., 2007; Steptoe and Wardle, 2001 or changes in cultural and wealth may also contribute to cross-country differences Juhasz et al., 2012. Moreover, discrepancies in recognition or identification of mental illnesses between the countries may exist Kirmayer, 2001.

While the prevalence rates for both probable depression and probable anxiety decreased from wave 7 (June/July 2021) to wave 8 (September 2021) in most countries, they often increased from wave 8 to wave 9 (December 2021/January 2022). The identified drop in prevalence rates from wave 7 to wave 8 may be mainly explained by improvements in vaccination coverage, whereas the rise in prevalence rates from wave 8 to wave 9 could be the result of increasing incidence rates (Winter 2021/2022), pandemic fatigue and a frequently higher Covid-19 stringency index.

In accordance with recent research Hajek et al., 2022, particularly high prevalence rates for both probable depression and probable anxiety have been identified among individuals aged 18 to 29 years in our study. We assume that being confronted with several challenges including financial obstacles, entering the labor market, worries about the future and filling multiple roles could explicate such remarkably high prevalence rates Hajek et al., 2022. Moreover, factors such as feelings of not really having experienced formative years may also explain the prevalence rates among individuals aged 18 to 29 years.

Additionally, individuals being infected with the SARS-CoV-2 also reported quite high prevalence rates in our study. While we assume that discrimination or Covid-19 related stigma Bagcchi, 2020; Duan et al., 2020 may only play a minor or negligible role more than one year after the beginning of the pandemic, we do assume that concerns about long-term health consequences of Covid-19 and concerns about (already) infecting relative or acquaintances may explain these prevalence rates in this group.

Moreover, individuals with great income difficulties reported very high prevalence rates in our study. Worsening living conditions, nutritional deficiencies, or harmful housing conditions Heflin and Iceland, 2009 caused by these income difficulties may explain these prevalence rates. Furthermore, worries about one's own future and the future of one's own family may also heavily contribute to these prevalence rates. Another way to explain such findings is that such individuals compare their income with others who are better off during the pandemic. These negative income comparisons may also explain these high prevalence rates Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2005.

Our longitudinal regression analyses also confirmed that increasing income difficulties can contribute to both increases in depressive symptoms and in anxiety symptoms – which may be explained by the aforementioned factors. Furthermore, our regressions showed that an increase in one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the coronavirus, the birth of a child and an increase in the Covid-19 stringency index were associated with increases in depressive symptoms. While an increase in the number of children (i.e., birth of a child) – at least in the short-term - commonly increases well-being (among women) prior to the pandemic Clark et al., 2008, the increase in depressive symptoms in our study may be explained by factors such as worries about infecting the child or feelings of overload due to the missing grandparents as a consequence of social distancing. Additionally, the association between an increase in the Covid-19 stringency index and increases in depressive symptoms could be explained by the perceived loss of freedom (and associated restrictions in social life or feelings of loneliness) due to the government measures. Lastly, the association between an increase in one's own perceived risk of getting infected with the coronavirus and increases in depressive symptoms in our study may be explained by the factors associated with such an infection (e.g., concerns about infecting others, or feelings of guilt when they may have already infected others).

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This current study substantially extends our knowledge regarding the prevalence of probable depression and anxiety during the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in various European countries. We used longitudinal data from the established and representative ECOS. The challenge of unobserved heterogeneity was reduced using linear FE regressions Cameron and Trivedi, 2005. It should be noted that good psychometric properties of the PHQ-4 have been shown by various studies [Kroenke et al., 2007; Kroenke et al., 2007; Kroenke et al., 2007; Löwe et al., 2005; Löwe et al., 2005. Additionally, Kroenke et al. declared that “because of its excellent operating characteristics, the PHQ–4 may well substitute for its parent scales (the GAD–7 and PHQ–9)” Kroenke et al., 2007. However, future research using clinical interviews would be useful to confirm our results. Moreover, future studies examining the prevalence of depression and anxiety among institutionalized individuals during later stages of the pandemic would be desirable. Moreover, it should be noted that the high risk group of individuals aged 80 years and above is underrepresented in such an online sample. In the present study, it was only distinguished between women and men. Future research among other gender identities ("diverse") may be of great interest during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.4. Conclusion

Our study is the first cross-country comparative analysis of mental health burden of COVID-19, with particular focus on later stages of the pandemic. In addition to shedding light on geographical differences, we find that younger individuals, those with income difficulties as well infected cases report major rates. These findings provide useful insights to inform policies aimed to heal fractures exacerbated by the pandemic.

Funding

This project has received funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) under project number 466310982 and the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 721402, the work was funding under the Excellence Strategy by the German federal and state governments, as well as by the University of Hamburg, Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management and Nova School of Business and Economics Lisbon–Chair BPI | “Fundação La Caixa” on Health Economics.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

André Hajek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Sebastian Neumann-Böhme: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Iryna Sabat: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Aleksandra Torbica: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jonas Schreyögg: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Pedro Pita Barros: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Tom Stargardt: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Hans-Helmut König: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Acknowledgments

None

References

- Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, Haro JM, Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Lépine JP, Ormel J, Polidori G, Russo LJ, Vilagut G, Almansa J, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Autonell J, Bernal M, Buist-Bouwman MA, Codony M, Domingo-Salvany A, Ferrer M, Joo SS, Martínez-Alonso M, Matschinger H, Mazzi F, Morgan Z, Morosini P, Palacín C, Romera B, Taub N, Vollebergh WAM. 12-Month comorbidity patterns and associated factors in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004;109(s420):28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association AP (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC.

- Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(7):782. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budimir S, Pieh C, Dale R, Probst T Severe Mental Health Symptoms during COVID-19: A Comparison of the United Kingdom and Austria. In: Healthcare, 2021. vol 2. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, p 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. Microeconometrics: methods and applications. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas RE. Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal. 2008;118(529):F222–F243. [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler MÉ, Howard ME, Robbins R, Barger LK, Facer-Childs ER, Rajaratnam SM, Czeisler CA. Early public adherence with and support for stay-at-home COVID-19 mitigation strategies despite adverse life impact: a transnational cross-sectional survey study in the United States and Australia. BMC public health. 2021;21(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10410-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;286:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, Bu H, Chen Z. COVID-19-related stigma profiles and risk factors among people who are at high risk of contagion. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell A. Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of public economics. 2005;89(5-6):997–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbar O, Gelkopf M, Berger R, Greene T. Stress and Health; 2022. Risk Factors for Depression and Anxiety During COVID-19 in Israel: A Two-Wave Study Before and During the Pandemic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek A, Sabat I, Neumann-Böhme S, Schreyögg J, Barros PP, Stargardt T, König H-H. Prevalence and determinants of probable depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in seven countries: Longitudinal evidence from the European COvid Survey (ECOS) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;299:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T, Angrist N, Goldszmidt R, Kira B, Petherick A, Phillips T, Webster S, Cameron-Blake E, Hallas L, Majumdar S. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, Iceland J. Poverty, material hardship, and depression. Social science quarterly. 2009;90(5):1051–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland P, Vallières F, McBride O, Murphy J, Shevlin M, Bentall RP, Butter S, Hartman TK, Karatzias T, MacLachlan M. Mental health of adults in Ireland during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a nationally representative, longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine. 2021:1–3. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721004360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F, Höfler M, Strehle J, Mack S, Gerschler A, Scholl L, Busch MA, Maske U, Hapke U, Gaebel W, Maier W, Wagner M, Zielasek J, Wittchen HU. Psychische Störungen in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. Der Nervenarzt. 2014;85(1):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3961-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Eszlari N, Pap D, Gonda X. Cultural differences in the development and characteristics of depression. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2012;14(4):259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2001;62:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care. 2003:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(5):317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-y, Choi D, Lee JJ. Depression, anxiety, and stress in South Korea general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology and Health. 2022 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2022018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) Journal of psychosomatic research. 2005;58(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, Schneider A, Brähler E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of affective disorders. 2010;122(1-2):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JJ, Baxter-King R, Vavreck L, Naeim A, Wenger N, Sepucha K, Stanton AL. Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Large, Longitudinal, Cross-sectional Survey. JMIR Mental Health. 2022;9(2):e33585. doi: 10.2196/33585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1999. Test theory: A unified treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Necho M, Tsehay M, Birkie M, Biset G, Tadesse E. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2021;67(7):892–906. doi: 10.1177/00207640211003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat I, Neuman-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Schreyögg J, Stargardt T. United but divided: Policy responses and people's perceptions in the EU during the COVID-19 outbreak. Health Policy. 2020;124(9):909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer ME, Stillman S (2006) XTOVERID: Stata module to calculate tests of overidentifying restrictions after xtreg, xtivreg, xtivreg2, xthtaylor.

- Shaw BP. Meeting assumptions in the estimation of reliability. The Stata Journal. 2021;21(4):1021–1027. doi: 10.1177/1536867x211063407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Goldberg D, Von Korff M, Üstün T. Understanding cross-national differences in depression prevalence. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(4):585–594. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Tsuda A, Tanaka Y. Depressive symptoms, socio-economic background, sense of control, and cultural factors in university students from 23 countries. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2007;14(2):97–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03004175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Wardle J. Health behaviour, risk awareness and emotional well-being in students from Eastern Europe and Western Europe. Social science & medicine. 2001;53(12):1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese NE, Sabat I, Neumann-Böhme S, Schreyögg J, Stargardt T, Torbica A, van Exel J, Barros PP, Brouwer W. Risk communication during COVID-19: A descriptive study on familiarity with, adherence to and trust in the WHO preventive measures. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]