Abstract

This paper presents results of a unique stated choice (SC) experiment to uncover the determinants of grocery shopping channel choice during the first wave of COVID-19 infections, where the most restrictive containment measures were in place. The choice sets were framed under regular and pandemic conditions, allowing for the estimation of pandemic-specific effects for each of the choice attributes. Our results show a significant overall increase of about 13%-points in online grocery shopping under pandemic conditions. Shopping and delivery costs were found to be the major decision drivers in both experimental settings, while the waiting time in front of the grocery store and risk of infection only played an secondary role. The value of delivery time savings (VDTS) decreases from about 10.8 CHF/day in the regular to 7.4 CHF/day in the pandemic case, indicating that respondents show an increased patience when waiting for the delivery of the ordered groceries. However, choice attributes related to the shopping trip, i.e. travel time and cost, do not show any notable effects. The COVID-19 death risk was valued rather low by the respondents and the relatively unrestricted Swiss containment measures are in line with the respondents’ average preferences, as shown by a relatively low value of statistical life (VSL) of about 800,000 CHF.

1. Introduction

Following the first death from the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland on March 5th, 2020, the Swiss Federal Council classified the outbreak of the SARS-COV-2 virus as an “extraordinary situation” under the Federal Epidemics Act (FDHA, 2020). This led to the closure of all non-essential businesses and public institutions, as well as the prohibition of gatherings of more than five people. Though no general curfew was put in place as in neighboring countries like France or Italy, the everyday life of the Swiss population has changed in unprecedented ways. For just over one month until mid-April 2020, Swiss residents were recommended to only leave the house for essential activities such as visiting a doctor or to go grocery shopping (FDHA, 2020). Hygienic regulations such as capacity constraints as well as the use of hand disinfectant and face masks were implemented at grocery stores in order to minimize the chances of customers infecting one another. The risk of becoming infected during a visit to the grocery store is especially relevant for high-risk individuals who represent a non-negligible segment of society and include adults of older age groups and those with medical preconditions (BAG, 2020).

Over the last decade, the online market for groceries has been growing steadily in Switzerland: in 2019 it accounted for 1.1 billion CHF yearly, representing 2.8% of the online shopping market, compared to only 1.8% in 2012 (VSV, 2020). Although there is a rich body of revealed-preference (RP) literature on shopping channel choice decisions, RP data is often problematic due to the high correlations between choice attributes and its limited trade-off information (e.g., Train, 2009, Schmid, 2019). Only little work has been done to date applying stated choice (SC) methods to explicitly model this decision process (Hsiao, 2009, Schmid et al., 2019). Sophisticated statistical methods like SC experiments and discrete choice models however allow to better understand the trade-offs individuals make in this regard, and allow to obtain meaningful attribute importance measures and willingness-to-pay indicators. To date, only Grashuis et al. (2020) have looked at these (similar) decisions under pandemic conditions. We designed a SC experiment to model the pandemic-related behavioral response regarding shopping channel choice for groceries in Switzerland. The experiment was performed with two different hypothetical settings to investigate a potential change in attribute sensitivities: one experiment is framing grocery shopping decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic with containment measures in place, and the other is considering shopping channel choice prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. We used an integrated choice and latent variable (ICLV) model including general risk aversion and shopping channel attitudes to obtain deeper behavioral insights on consumer heterogeneity. Our framework simultaneously estimates the pandemic-related effects on the decision-driving attributes, the direct and indirect effects of socio-demographic characteristics on these factors, as well as additional respondent heterogeneity that arises from different attitudes.

The reminder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents relevant work and the latest findings regarding behavioral models for online grocery shopping. Section 3 gives an overview about our survey tool, the experimental design and the modeling methodology. Section 4 describes the modeling results. Section 5 provides a conclusion and critical reflection.

2. Literature Review

Grocery shopping is a rather unique form of shopping for several reasons, and its effects on related demand for transportation and mobility have been studied thoroughly. Shopping for groceries is firstly the most common and frequent shopping trip purpose (Suel and Polak, 2017). Groceries are considered to be experience goods, as their physical attributes are best inspected in person. They do not require separate visits for information gathering and are therefore less likely to be bought online compared to search goods, such as electronics or furniture (Peterson et al., 1997, Rudolph et al., 2015, Schmid and Axhausen, 2019). The effects of information and communication technologies (ICT) have been of interest to the field of online shopping, especially in the last 25 years, and they are assumed to either substitute, complement, modify, or not at all alter travel behavior to physical stores (Mokhtarian, 2004). Since groceries are predominately still purchased in-store, online shopping can be seen as a shopping channel with great potential, implying possible substitution effects (Farag, 2006, Suel and Polak, 2018, Dias et al., 2019, Zhai et al., 2017).

Concerning in-store and online grocery shopping during the pandemic, many studies have reported substantial increases and large potentials in online market shares among different consumer segments (e.g., Bezirgani and Lachapelle, 2021, Guzman et al., 2021, Pawar et al., 2021, Colaço and Silva, 2022). In case of Switzerland, the Swiss Retailer Survey for 2020 shows a remarkable 75% increase in sales for online grocery shoppers (Zumstein and Oswald, 2020). The question that follows is what factors motivated this stark increase in online grocery shopping behaviors and what role pandemic effects play in this decision-making process. A shift toward online grocery shopping was even evident in Asian countries where the norm is to purchase fruits and vegetables daily at outdoor markets; the reason being, unsurprisingly, that individuals do not want to take the unnecessary risk of potentially becoming infected (Chang, 2020). According to Wang et al., 2020, the main reason individuals reported stockpiling groceries was actually to ”go out less” and not foremost out of worry that products would run out or that prices would increase dramatically. Their estimates of willingness to pay for fresh foods are in line with an increase of 60% during COVID-19. A similar increase was identified by Wang et al., 2021, who saw the number of people ordering groceries online grow by 113% during the pandemic, though only about 50% would continue to do so afterwards. Almost all studies that consider these choices pre-pandemic tend to simply highlight the importance and sensitivity of cost as opposed to time (e.g., (Schmid and Axhausen, 2019, Rossolov et al., 2021, Marcucci et al., 2021)). The pandemic clearly added new attributes into the choice situation that cannot be neglected when investigating shopping channel preferences.

Few studies to date have taken shopping channel choice behavior into a stated choice experiment survey. Hsiao, 2009 focused on travel time and delivery time valuation in the context of books, a typical search good, and found that physically visiting a bookstore to purchase a book provided by far more disutility than having to wait for a book to be delivered. Similarly, Schmid and Axhausen, 2019 used SC experiments to investigate how individuals trade off attributes related to shopping channel choice for both experience and search goods, in their case in a hypothetical setting in which private vehicles did not exist. A major conclusion drawn was that respondents with a higher education typically exhibit a more positive attitude toward online shopping and are hence those who more often choose the online alternative for grocery purchases. In another study out of Norway, Marcucci et al., 2021 also took a stated preference approach to understand consumer channel choice and found the main drivers steering this choice to again be related to cost: product price and service cost. With the dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic, Grashuis et al., 2020 implemented a SC experiment to investigate grocery shopping channel choice using an online panel with 900 participants. They looked at the attributes of purchasing method (online purchase, in-store pickup, or in-store purchase), fees, minimum order amount, and time window. They found that participants in the scenario in which COVID-19 rates in their area were increasing were the least willing to purchase groceries in-store and no preference for purchasing method in a scenario in which COVID-19 rates were decreasing in an area. The option to opt-out of going shopping in person shared similar importance to the purchasing method, and the fees associated with the shopping method contributed to respondents’ disutility to an even larger extent. Though these findings are important, their approach was limited as they did not account for potential effects of socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics on these decisions.

3. Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

We implemented two different SC experiments, one positing regular (pre-COVID-19) conditions and the other in a pandemic context. The SC experiments were implemented in a within-subject design, i.e. both treatment conditions were shown to each respondent. The hypothetical scenario descriptions for both experiments were designed to ensure realistic and intuitive consequences of the decisions, as well as logical and understandable relationships between the traded goods (see Table A1, Table A2). Table 1 shows an overview of the attributes of the alternatives in both experiments. In the regular setting, the in-store alternative is described by shopping cost and shopping time, as well as travel cost and travel time. The online alternative is characterized by shopping cost and shopping time, as well as delivery cost and delivery time. In the pandemic setting, the in-store alternative additionally includes attributes of waiting time in front of the store and risk of infection.

Table 1.

Choice set composition and overview about the relevant attributes for both experiments.

| attributes | treatment |

alternatives |

levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pandemic | regular | in-store | online | |||

| shopping cost [CHF] | x | x | x | x | Appendix, Table A3 | |

| shopping time [min] | x | x | x | x | Appendix, Table A4 | |

| travel cost [CHF] | x | x | x | Appendix, Table A7 | ||

| travel time [min] | x | x | x | Appendix, Table A8 | ||

| delivery cost [CHF] | x | x | x | 10, 25, 50 | ||

| delivery time [h] | x | x | x | 6, 24, 48 | ||

| waiting time [min] | x | x | 0, 10, 20 | |||

| risk [-] | x | x | low, mid, high | |||

The shopping costs for the in-store alternative are based on three different basket sizes (small, medium, large) for typical Swiss grocery shopping quantities (Schmid et al., 2019). The shopping costs for the online alternative were derived using a fixed discount compared to in-store prices, which we set to 10%. Moreover, shopping costs for the in-store and online alternatives were further varied over three levels according to Table A3. The shopping duration is linked to the basket sizes according to Table A4. The average values for each basket in the in-store alternative are based on Schmid et al., 2019, whereas those for the online alternative were set to be five minutes shorter. The travel times are based on the respondents’ typical mode of transport when going grocery shopping. The travel costs are also based on the mode of transport and further depend on whether respondents have a local public transport (PT) subscription. Respondents were able to choose between PT, on foot/bike and car (including motorbike) resulting in four different classes of choice sets. The average travel time and travel cost values for those four choice set classes are based on the Swiss Mobility and Transport Microcensus (MTMC) and vary over three levels according to Table A7, Table A8. The delivery times and delivery costs are both based on current market values in Switzerland. The typical value for the former is delivery within the same day or 24 hours after ordering. The corresponding attribute levels are shown in Table 1. Delivery within 48 hours is typically not offered in context of grocery shopping, but was included in the experiment to cover potentially longer delivery times due to pandemic-related delays (Queiroz et al., 2020). The delivery costs typically range around 10 CHF and the attribute levels were set to range from 10 CHF to 50 CHF in order to capture a high willingness-to-pay.

The two final attributes are only included in the pandemic treatment. The waiting time accounts for any queues forming in front of grocery stores. The risk attribute is used to frame three different stages (low, moderate, high) of the pandemic spreading with three different risks of becoming infected. The stages are defined according to Table A1, with the numbers of infections and recoveries based on an Susceptible, Infected and Recovered (SIR) infection model from April 2020 (Noll et al., 2020), using different assumptions for the basic reproduction number . Additionally to Table A1, respondents were shown Table A2 depicting the probabilities of different COVID-19 symptoms to better contextualize the actual risks that come with a SARS-COV-2 infection. Those probabilities are based on an early study of Verity et al., 2020 and valid for a person of 43 years of age. The design resulted in twelve different classes. In each class, the levels of relevant attributes yielded 729 possible combinations for the pandemic experiment, and 81 possible combinations for the regular one. For each class, we extracted 40 choice sets from the candidate sets using a D-efficient design (Rose and Bliemer, 2009) in Ngene (ChoiceMetrics, 2014). The 40 choice sets were split into ten blocks to which respondents were randomly allocated to. Within a single block, participants had four experimental situations to evaluate. The order and graphical presentation of the choice sets, were randomly varied throughout the sample in order to eliminate potential order effects (Farrar and Ryan, 1999, de et al., 2012).

After respondents passed the SC section of the survey, an additional set of questions were asked in order to obtain an idea of respondents’ attitudes towards online shopping and risk behavior. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted in order to determine how many latent constructs should be derived. Based on the Kaiser criterion (Yeomans and Golder, 1982), a single latent construct was derived for each set of items. The questions related to online shopping preferences consisted of nine Likert scale items, see Appendix A5, based on Schmid and Axhausen (2019). Each item’s factor loading (based on a previously conducted factor analysis) is provided in brackets, defining a latent construct that we define as pro-online shopping attitudes. The attitudes towards risk behavior were assessed using six different seven-point Likert scale items (low vs. high chance of engaging in certain activity), which are based on Blais and Weber (2006),see Appendix A6. Each item’s factor loading is provided in brackets, defining a latent construct that we define as pro-risk attitudes

3.2. Modelling Framework

The ICLV model consists of three main components: a choice model, a LV measurement and a LV structural model. The LV measurement model estimates the LV that explains the answers to the attitudinal items, while the choice model uses the LV in addition to other common explanatory variables like choice attributes and socio-demographic characteristics to explain the respondents’ choices. Furthermore, the structural model defines the LV based on socio-demographic characteristics and an error component. Estimating all three components sequentially forces to first fit the LV which comes with reduced statistical modelling flexibility and has shown to provide inconsistent parameter estimates (Bouscasse, 2018, Bhat and Dubey, 2014).

Choice Model

The utility equations of the most exhaustive choice (ICLV) model are presented in Eqs. 1 to 3. The two shopping channels are denoted as for in-store (S) and online (O). Respondents are denoted as and the choice set by . Both LVs are denoted as with for the pro-online (PO) and the pro-risk (PR) attitudes.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

is a vector of alternative-specific choice attributes with dimensions holding all K choice attributes while the first column has an entry of 1 to account for the alternative-specific constant (ASC). While both functions include the same set of choice attributes in the regular experiment, the in-store alternative additionally includes the waiting time and risk attribute in the pandemic experiment. The risk attribute was incorporated in a discrete manner, as we did not assume a linear relationship between the characteristics that define the different risk levels (see Table A1, Table A2). All cost parameters were modeled by applying negative log-normal distributions (i.e. ; see Eq. 3) to ensure negative utility weights. Based on previous tests, both LVs were only added to the ASC of the online shopping utility function (note that the in-store alternative is set as reference alternative; first column of is set to zero). The vector refers to the corresponding alternative-specific parameters and has the dimensions . It is defined according to Eq. 3, and consists of each choice attribute’s main effect parameter and additional interaction parameters. Those include respondent-specific socio-demographic characteristics that are represented through the vector with its parameters , as well as choice set-specific dummy variables that indicate the basket size and reported mode of transport, represented through the vector and its parameters . Each of the parameter vectors ( and ) in Eq. 3 vary according to the pandemic situation. To investigate the differences in attribute sensitivities and socio-demographic effects before and during the pandemic, interaction effects with the pandemic situation (included as dummy variable ) were also included, where pre-pandemic is the reference (i.e. all parameters with subscript P were added to the pre-pandemic effects to obtain the actual effects; see also Table 2 ).1 The values in and were transformed using weighted effect coding, which centers each variable in such way that the weighted mean equals zero (Grotenhuis et al., 2017). This enables a straightforward interpretation of socio-demographic interaction effects as deviations from the sample mean, leaving the main effect unaffected.

Table 2.

Model estimation results.

| Reference alternative: In-store shopping (S) | Coef. | Coef. | Coef. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | |||

| –0.05 | |||

| 0.09 | |||

| –0.09 | |||

| –0.04 | |||

| –0.02 | |||

| 0.16 | |||

| 0.40 | |||

| –0.06 | |||

| 0.21 | |||

| –0.20 | |||

| 0.33 | |||

| Estimated parameters | 57 | 71 | 79 |

| Respondents | 1009 | 1009 | 1009 |

| Choice observations | 8072 | 8072 | 8072 |

| Draws | 5000 | 5000 | 5000 |

| LL(null) | -5082.75 | -5082.75 | – |

| LL(choicemodel) | -2613.80 | -2576.94 | -2615.26 |

| AICc(choicemodel) | 5348.55 | 5306.79 | 5353.72 |

, ,

Note: Shopping and delivery cost are scaled down by factor 100.

Note: Waiting time is scaled down by factor 60, delivery time by factor 24.

In order to account for unobserved heterogeneity and correlations across choices, we added independent normally distributed random components to the ASC of the online shopping utility. The random components were further added to each choice attribute to capture unobserved taste heterogeneity on an attribute level (Greene et al., 2006). The components capture the remaining alternative-specific error terms that are assumed to be independently and identically distributed (IID) extreme value type I.

Latent Variable Model

The structural equation of the LVs is given in Eq. 5 and is a linear functions of observable socio-demographic characteristics and a random error component. The vector represents the socio-demographic characteristics as used for the parameter interaction terms in Eq. 3 of the choice model, but does not necessarily include the exact same characteristics. represents the matrix of corresponding parameters (one row per LV and sufficient columns for all ). The term represents a normally distributed zero-mean random error term.

| (5) |

| (6) |

The measurement model for the attitudinal indicator questions is given in Eq. 6. For each respondent n the w-th attitudinal indicator/item with is defined as the mean value of each indicator over all respondents plus the explanatory part of the LV with its corresponding parameters . The mean indicator values were calculated beforehand and allowed to center each indicator around 0, thus avoiding to estimate a constant for each (Kløjgaard and Hess, 2014). Finally, the term represents a normally-distributed zero-mean random error term. For each LV, the first (i.e. shop1 and risk1) is normalized to one for identification purposes.

Estimation

The models are estimated using simulation of the joint likelihood function (choice and latent variable model; for more details see e.g., Walker and Ben-Akiva, 2002, Vij and Walker, 2016) which was evaluated for a large number of Sobol draws (Czajkowski and Budzinski, 2019) from independent multivariate normal distributions. We investigated the numerical stability of the models using increasing number of draws, reaching a stable solution with 5,000 draws. The models are estimated in R using the mixl package (Molloy et al., 2019) using cluster-robust (at the individual-level) standard errors.

4. Results

The survey was conducted in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. We only considered individuals who regularly go grocery shopping themselves. We used an internet access panel provider for the survey distribution that applied sampling quotas based on the MTMC, and collected a sample of 1,009 respondents. The survey distribution lasted from April 21st, 2020, by which time the Swiss population had already spent five weeks in self-isolation, to May 25th, 2020. Approximately 80% of the responses were collected within the first week. The survey hence covers the period in which the most restrictive containment measures were in place, making our dataset unique due to these likely never reoccurring experimental conditions. An overview about the dataset’s descriptives is shown in Table A9, including the MTMC data as reference whenever applicable. The final dataset contains a total of 8,072 choice observations, thereof half are described under regular (pre-pandemic) conditions and the other half under pandemic conditions. The distribution of gender, education, household size and household income approximately match the representative MTMC data. The collected sample is biased towards retired, older age groups, as the panel provider does not differentiate between age groups over 60. Approximately two thirds of the sample have never shopped online for groceries.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Choice Behavior

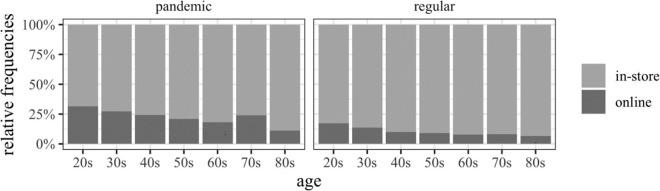

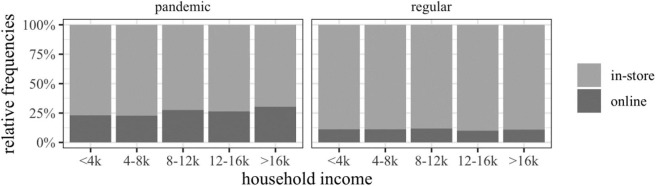

Table A9 in the Appendix describes the choice behavior for the two different experiment settings at the most aggregate level and differentiated between respondents with and without previous grocery online shopping (GOS) experience. On the one hand, these numbers are consistent with the previously mentioned low penetration rate of online grocery services in Switzerland (VSV, 2020). On the other hand, it can be seen that the pandemic setting clearly influences the choice behavior, where 13%-points of shopping choices are substituted by the online channel. This increase is evenly distributed in the groups with and without previous GOS experience. Fig. 1, Fig. 2 show the choice behavior (i.e., the market shares of online and in-store shopping) for different age and income categories, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Choice behavior by age groups for pandemic (left) and regular (right) experiment setting.

Fig. 2.

Choice behavior by income for pandemic (left) and regular (right) experiment setting.

Both show clear signs of a behavioral change in favor of the online alternative induced through the pandemic conditions. All age and income groups show an increased frequency of online choices, an increase that seems to be negatively correlated with age, potentially related to ICT-aversion. Only the age group of 70-80 does not follow this pattern, which may be explained by the disproportionately higher health risk that individuals of that group have. Household income appears to be positively related to the choice of the online channel in the pandemic case, likely attributable to a higher purchasing power and frequency. However, no such trend could be observed in the regular case.

4.2. Model Estimation Results

We applied a bottom-up modeling approach in which we started with a simple multinomial logit model, , that served as base model. We then gradually increased the model complexity over multiple model formulations and only kept the parameters which are statistically significant at the 10% level after each modeling iteration in order to keep the model complexity manageable. The second model and third model add dummy variables which indicate the choice set shown to the respondent (dependent on randomly assigned basket size and reported mode of transport for the usual shopping trip), as well as socio-demographic interaction effects, respectively. The fourth model, MIXL, is a reduced-form mixed logit model that adds multiple random components to account for unobserved heterogeneity in respondents’ choices (e.g., Vij and Walker, 2016). The fifth and sixth models, and ICLV, additionally incorporate the effects of respondents’ attitudes on the individual decisions. The directly uses factor scores of the previously conducted factor analysis. Although this is known to be inappropriate because the factor scores enter the model as exogenous variables, estimating such simplified models helps for the subsequent development of the ICLV model (Schmid and Axhausen, 2019). ICLV models are considered common practice as they account for measurement error and endogeneity issues as opposed to directly incorporating the factor scores (Ben-Akiva et al., 2002, Kløjgaard and Hess, 2014, Hess and Beharr-Borg, 2011). The estimation results for the (basic MNL model with regular vs. pandemic main effects), (adding the choice set indicators) and (adding the socio-demographic characteristics) model are provided in Table A10 in the Appendix. The parameter estimates for the and ICLV model are shown in Table 2.

After evaluating different model formulations regarding the main effects , previous investigations have shown that the shopping time, travel cost and travel time parameters were always insignificant with values close to zero. This is most likely because of two reasons: the experimental setting had a strong emphasis on the pandemic context and the attribute values were negligible compared to their mutual counterparts (e.g. shopping cost vs. travel cost). The remaining main effect parameters are consistent and significant throughout all model formulations. However, they show a distinct change in scale when comparing the models with and without random components (i.e. Table 2 vs. Table A10, respectively). Moreover, multiple interaction effects lose their significance when introducing the random components in the MIXL model.

The model includes the (ASC and interaction with choice attributes) effects of the pro-online shopping and pro-risk factor scores. This model mainly serves a pre-step to the ICLV model by investigating the actual benefit of including attitudes in the choice model. Importantly, none of the interaction effects is significant (except a less negative high risk effect for respondents with a higher pro-risk score, which was only significant at the 10% level). Overall, the pro-risk factor scores are only adding marginal explanatory power, while the pro-online shopping factor scores have a strong and positive effect on the utility of online shopping. Therefore, the LV capturing risk behavior is excluded in the final ICLV model, since it did not add any substantial explanatory power, and all interaction effects between the pro-online shopping LV and choice attributes were excluded as well.

The following section focuses on the most exhaustive ICLV model results and discusses the parameter estimates in detail. Important to note is that all random components are highly significant, indicating a substantial amount of unobserved heterogeneity between participants, and that the parameter estimates (same signs and magnitudes) are consistent between the different model formulations. Focusing on observable characteristics, results indicate that male respondents exhibit a higher choice probability of online shopping than female respondents, as shown by the increased ASC. This is in line with literature about preferences towards online shopping in general, but not necessarily groceries, e.g. Ramachandran et al., 2011, Schmid et al., 2019. We also obtain the expected effect of age, indicating that older respondents experience online shopping more negatively than younger respondents. This seems reasonable as older respondents may be more reluctant to order groceries online because it’s not something they are as familiar with. When looking at the effects on the ASC during the pandemic case, we only found a positive effect of income: Higher-income individuals experience an increased utility from online grocery shopping, as already shown in Fig. 2. This is in line with studies that remark that online shoppers are typically higher-income individuals, as shown in e.g. Farag et al. (2003) and Schmid et al. (2019). Being Swiss imposes a certain reluctance towards online grocery shopping, which could be reflective of Swiss individuals’ cult-like preferences for one grocery store chain over another, and/or just more traditional shopping preferences as their foreign counterparts.

When looking the effects of shopping and delivery cost, it is important to keep in mind that they were modeled using a negative log-normal distribution, i.e. their effects on the utility are always negative although corresponding main effect parameters may have signs in both directions. Importantly, a significant change in the cost sensitivities during the pandemic could not be found, although the effect of shopping cost becomes substantially less strong as indicated by the negative sign of the pandemic interaction effect (e.g. ICLV model: pre-pandemic/regular main effect = –exp(1.80); pandemic main effect = –exp(1.80 – 0.32)). Importantly, a smaller sensitivity of shopping and delivery costs for higher income could not be not found, which may be explained by the relatively low share of grocery expenditures and the wealthy Swiss population (Schmid et al., 2019). There is a significant interaction effect of large basket size on shopping cost, reflecting a higher sensitivity to cost when spending larger amounts. The coefficient of delivery cost is similar in magnitude to that of shopping cost and not significantly different during the pandemic, indicating a context-independent disutility of money. Importantly, however, this does not hold for travel costs (i.e. they are not affecting choice behavior significantly; a similar result was found in Schmid and Axhausen (2019)). The interaction effect for individuals who go grocery shopping by public transport as opposed to active modes or car is interesting. Individuals do not mind paying more to have groceries delivered because the in-store alternative is associated with a potentially risky PT trip to the grocery store (see the positive safety perception associated with active modes during the pandemic reported in Pawar et al. (2021)). The coefficient of delivery time has the expected negative effect on utility, however this effect decreases under pandemic conditions, i.e. waiting longer for groceries to arrive is perceived less negatively. One may simply be grateful that groceries will arrive at their doorstep without having to leave home. Interaction effects of medium basket size and respondents who use public transport to go grocery shopping do not offer clear explanations. The interaction effect of delivery time and retired respondents could potentially be explained by the fact that they have less time-pressure than non-retired individuals.

There is a significant negative effect of waiting time, as waiting to enter a grocery store during the pandemic entails both wasting time in an uncomfortable situation and potentially becoming exposed to COVID-19. Waiting time also did not show any significant interaction effects with income or age, which was surprising since older adults have a substantially higher risk of a fatal disease course. There is, however, a significant negative interaction effect for individuals who go grocery shopping with their cars. Car users likely feel safe in their private car on the way to buy groceries but then become particularly sensitive when waiting an extended period of time among other people. The interaction effect of household size on waiting time reflects a decreasing sensitivity for larger households, leaving room for speculation why this is exactly the case.

With low risk as a reference level, medium and high risk levels of becoming infected both show significant and negative effects on the utility of in-store shopping. Notably, the magnitude of the coefficient for a high risk level is almost five times larger than that of a medium risk level, which goes in line with the ratio of risk magnitudes described in the framing of the experiment. The interactions with education level are highly significant for both risk levels and indicate that having completed some form of higher education after compulsory schooling reflects a substantially higher risk sensitivity, probably because higher educated individuals better understand the actual health implications of a COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, the ratio of the effects of both education levels for the two different risk levels are intuitive, consistent and significant for all model specifications. The interaction effect with income, even though only significant for the medium risk level, is positive, which is consistent with the positive correlation of the pro-risk LV and income in Fig. 1. However, other interaction effects, as e.g. with age, could not be found.

As expected, the LV capturing pro-online shopping attitudes has a strong positive and significant effect on the ASC, as mentioned above. The coefficients of attitudinal items as well as the respective of the LV measurement model are all highly significant, and the former confirm the signs of the previously conducted factor analysis. A positive value of the LV hence indicates that respondents exhibit positive attitudes towards online shopping. The parameters of the LV structural model reveal that only income (p < 0.01) and retirement (p < 0.05; positively correlated with age) have significant explanatory power. Both effects are as expected: income has a positive effect while retirement has a negative one, a similar result that has been found in Schmid and Axhausen (2019). The latter is also in line with findings from Bezirgani and Lachapelle (2021), where the online shopping behavior of elderly people was studied. It must be noted that the LV is mainly defined by the random component, such that most available socio-demographic characteristics cannot be used for forecasting choice behavior via the LV.

Finally, a parameter decomposition is conducted for those socio-demographic characteristics that have a significant effect on the LV (i.e. income and retirement). While in the reduced-form MIXL model, we directly measure the total effects of socio-demographic characteristics on the utility, in the ICLV model we allow for a mediation via the attitudes (in the current case by only affecting the ASC, since the interaction effects were all negligible), which are the indirect effects. The sum of direct and indirect effect is the total effect (Vij and Walker, 2016, Schmid et al., 2019). It is interesting to see that retirement only has an indirect effect (i.e. 2.79 –0.09 = –0.25; p < 0.05); the direct effect was not significantly different from zero in both the regular and pandemic setting. Thus, retired respondents exhibit lower pro-online shopping attitudes, which decreases the utility of online shopping indirectly. The direct effect of income (0.77; p < 0.01) is only significant and positive in the pandemic case (and not significant in the regular setting), while the indirect effect is significant and positive in both (i.e. 2.79 0.07 = 0.20; p < 0.01). The total effect of income in the pandemic case (0.97; p < 0.01) is thus strengthened by the indirect one, while the total effect in the regular case (0.2; p < 0.01) is substantially smaller.

4.3. Partworth Analysis

The partworth analysis allows to quantify the relative weight of each choice attribute within the decision making process of respondents (e.g., Kuhfeld, 2010, Schmid et al., 2022). As opposed to just considering individual parameter estimates, the partworth analysis takes into account the parameter as well as the values of each attribute to measure their actual relevance in the utility function. Based on the ICLV model, we calculate the individual-level taste parameters from the posterior distributions by applying Bayes’ rule (using 5,000 draws) (e.g., Revelt and Train, 2011) and multiply those with the average of the corresponding attribute values of the respondents’ choice sets. This dimensionless measure provides information on the attributes’ average importance in the utility function of each respondent, which we then average over all respondents. To calculate the relative partworth of each attribute, we further take the absolute values and calculate the %-share of the total partworth. This procedure is conducted for both experimental settings separately in order to show the pandemic-related changes of the attributes’ importance, as presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Relative importance of choice attributes ( model).

| attribute | relative partworths [%] |

|

|---|---|---|

| regular | pandemic | |

| shopping cost | ||

| delivery cost | ||

| delivery time | ||

| waiting time | ||

| medium risk | ||

| high risk | ||

Under regular conditions, it can be seen that the shopping and delivery costs are the two main decision drivers, while the effect of delivery time is comparably small. Considering the pandemic context reveals interesting insights. The cost attributes are still the major decision drivers, but shopping cost is not perceived as important as in the regular case, losing approximately 15% of importance. Delivery time only accounts for around 6% of the relative partworth, slightly less than under regular conditions. The waiting time is of negligible importance, and for the risk-related attributes, only the high risk has a notable effect on the decision making process, which is, however, still small compared to the cost attributes. This result is in line with the relatively relaxed perception of the COVID-19 pandemic by the Swiss population and the generally less restrictive containment measures taken by the Swiss government compared to its neighboring countries (e.g., Swissinfo.ch, 2020), indicating that economic factors still play a dominant role in the respondents’ decision making process.

4.4. Marginal Probability Effects

The marginal probability effects (MPE) describe the change in choice probabilities when attribute is changed while all others are kept unchanged (e.g., Winkelmann, 2006). Following Schmid et al. (2022) we approximate the MPE by calculating the difference in initial probabilities with those obtained when the variables of interest are changed by a certain amount. For continuous variables we impose a 10% increase, while for pseudo-continuous (i.e. linearized; age and income) and discrete variables, we impose a discrete change. The resulting MPE are shown in Table 4 . Analog to the previously mentioned pattern of parameter estimates between models with and without random components, the MPEs show similar patterns and are consistent within and between their model class. Table 4 hence provides the MPE for the (without random components) and the ICLV model (with random components).

Table 4.

Marginal probability effects.

| online choice increase [%-points] |

||

|---|---|---|

| pandemic (dummy) | ||

| basket size: medium (dummy) | ||

| basket size: large (dummy) | ||

| mode: public transport (dummy) | ||

| mode: car (dummy) | ||

| shopping cost, online (+10%) | ||

| shopping cost, in-store (+10%) | ||

| delivery cost (+10%) | ||

| delivery time (+10%) | ||

| waiting time (+10%) | ||

| medium risk (dummy) | ||

| high risk (dummy) | ||

| age (+10 years) | ||

| male (dummy) | ||

| income (+2k CHF) | ||

| medium education (dummy) | ||

| high education (dummy) | ||

| working (dummy) | ||

| retired (dummy) | ||

| swiss (dummy) | ||

The MPE in both models are qualitatively comparable for most variables, yet with small differences in magnitudes. The most distinct difference applies to the treatment effect, which differentiates between the regular and pandemic experimental settings with an MPE more than twice as large in the ICLV model (10.2%-points increase in the pandemic case). Clearly, the latter result is more accurate and better reflects the observed market shares discussed in the descriptive analysis (13%-points increase). Considering the socio-demographic characteristics, the largest effects arise for Swiss citizens as well as public transport users, each with a decrease and increase of around 7%-points, respectively. The latter goes in line with the interaction effects of public transport users in Table 2 which indicate a lower sensitivity for online shopping related attributes like delivery cost and delivery time. The relatively large effect of being Swiss may be due to the fact that Swiss citizens are more reluctant towards new technologies and/or have more traditional shopping preferences, as discussed in Section 4.2. Further notable effects are found for education and working status, where all four variables are in line with previous patterns discussed in Section 4.2.

When first looking at the continuous choice attributes, shopping cost (both online and in-store) is the strongest predictor for shopping channel choice, while the delivery related attributes only have small effects. Importantly, the MPE of regular (non-pandemic) choice attributes such as shopping cost, delivery cost and delivery time are similar to the results presented in Schmid and Axhausen (2019) for the Canton of Zurich, where shopping cost also exhibited the strongest effect with an MPE of about 3%-points (for a 10% increase). Waiting time has the smallest effect of all continuous choice attributes, which goes in line with the rather low importance found in the partworth analysis (Section 4.3). For the pandemic-related attributes, a high risk of infection shows a substantial MPE of about 13.5%-points compared to the reference category (low risk), which is more than four times larger compared to a medium risk of infection (3%-points increase).

4.5. Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) Indicators

The estimated model parameters allow to derive WTP indicators for the different choice attributes. We show the resulting WTP indicators for the and the ICLV model, each being chosen as representative for models with and without random components, respectively. The WTP indicators are obtained by calculating the ratio between the posterior parameter estimates (see also Section 4.3) of the attribute of interest and the generalized cost parameter (Hole, 2007, Schmid et al., 2019). Following Hensher (2011) we apply a weighted average to both cost parameters (shopping and delivery cost) in order to obtain one generalized cost parameter. Table 5 shows the resulting WTP indicators. It can be seen that the magnitudes of the different measures differ considerably between the both model types, considering those from the ICLV model to be more accurate estimates, given the more dedicated treatment of respondent heterogeneity.2

Table 5.

Mean valuation indicators.

| indicator/attribute | willingness-to-pay |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| delivery time (VDTS), regular | [CHF/day] | ||

| delivery time (VDTS), pandemic | [CHF/day] | ||

| waiting time | [CHF/h] | ||

| medium risk | [CHF] | ||

| high risk | [CHF] | ||

Given our unique experimental design, we can derive the Value of Delivery Time Savings (VDTS) under regular and pandemic conditions. While the pandemic conditions do not show a large difference in the model, they clearly do so in the ICLV model, where the VDTS in the pandemic case decreases by around 30%. This reflects the previously mentioned finding that the delivery time sensitivity decreases under pandemic conditions. The VDTS under regular conditions of 10.8 CHF/day for groceries are comparable with those found in Schmid and Axhausen (2019) of around 10 CHF/day and underpin the validity of our data and modeling approach. The WTP to reduce the waiting time in front of grocery stores cannot directly be compared to previous findings, as our experimental design is the first of its kind allowing the estimation of this measure. Allon et al. (2011) have estimated the value of waiting time in queues for drive-through restaurants with lower bound values reaching 40 USD/h which are comparable to the 33 CHF/h obtained in the model, while Schmid (2019) have estimated a rather high value of waiting time at the checkout in supermarkets of about 65 EUR/h.

The WTP measures for a risk reduction allow to derive a rough estimate of the Value of Statistical Life (VSL). The VSL measures the aggregated WTP for a collective marginal risk reduction that adds up to 100%, i.e. one statistical life. Using the death risks which are inherent in the risk attributes of our experimental design (see Table A1, Table A2 in the Appendix) and the obtained generalized cost parameter, for the ICLV model we obtain a VSL estimate of about 800,000 CHF (which is consistent for both risk levels). In the context of COVID-19 related VSL studies, this value is substantially lower than estimates from e.g. Chorus et al. (2020) of around 2 Million EUR which results from data recorded under similar pandemic conditions, as well as general values of approximately 6.5 Million CHF which are used for accident and health risk reduction valuations in Switzerland (ARE, 2019).

5. Conclusion

This paper presents results of a stated choice (SC) experiment to elicit the decision drivers of grocery shopping channel choice. The survey was conducted in Switzerland during the early phase of the lockdown period in April 2020 after the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The data were modeled using an ICLV model to account for observed and unobserved taste heterogeneity as well as attitudes towards online shopping. The descriptive analysis of the choice behavior indicates that in either case (pandemic and regular), respondents prefer to shop groceries in-store. However, there is a clear substitution effect in favor of online shopping in the pandemic case, which is also well reproduced by the marginal probability effect (MPE) in the ICLV model. This increase is in line with the numbers reported from retailers in Switzerland (Zumstein and Oswald, 2020) and the general observation that people try to avoid crowded places such as grocery stores to reduce the risk of a COVID-19 infection. Also, when considering the pandemic-specific choice attributes, a high risk level has a very strong effect, which goes in line with the findings of Grashuis et al. (2020).

Choice attributes related to the shopping trip, i.e. travel time and cost, do not show any notable effects throughout either of the model formulations, which we believe is mostly related to the experimental setting that had a focus on the pandemic-related attributes such as infection risk and waiting time in front of the grocery store. Said attributes exhibit strong and expected effects, with their absolute and relative values being consistent with the expectations. Strong and persistent effects are also found for shopping and delivery costs, both showing similar (i.e. context-independent) cost sensitivities of respondents. Accounting for random heterogeneity again increases the estimated cost sensitivity, which directly translates into decreased WTP indicators for a decrease in delivery time, waiting time and risk of infection. Interestingly, results of a partworth analysis show that shopping and delivery cost are the most important choice attributes also in the pandemic case, while the risk of infection is perceived as rather unimportant, underlining the relatively relaxed attitudes of the Swiss population in context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results also suggest that the COVID-19 death risk as presented in our experimental framing was valued rather low by the respondents, and that the relatively unrestricted Swiss containment measures are in line with the respondents’ average preferences (i.e. value of statistical life; VSL) – at least as far as we can conclude it from the current experimental context on shopping channel choice.

In the models with random components, the pandemic condition only exhibits a significant effect on the delivery time sensitivity, but not on shopping and delivery cost sensitivity. Results show that the value of delivery time savings (VDTS) decreases from about 10.8 CHF/day in the regular to 7.4 CHF/day in the pandemic case, indicating that respondents show an increased patience when waiting for the delivery of the ordered groceries. Results are comparable to a similar study conducted in Zurich, Switzerland, where the WTP and MPE in the non-pandemic case lie in similar range (Schmid and Axhausen, 2019). The attitudes towards online shopping exhibit a strong effect on utility, but the corresponding LV structural equation is mostly driven by random heterogeneity, where only income (positive) and retirement (negative) show a significant effect on the LV. Compared to the reduced-form MIXL model, including attitudes in the choice model does not affect results substantially, concluding that in the current case incorporating the LV did not add a substantial improvement of behavioral insights.

This paper contributes to the general body of knowledge regarding behavioral adaptions of shopping channel choice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While the generated insights cannot be generally applied to any place or population in the world, they are of specific relevance to countries similar to Switzerland, i.e. western, highly developed countries. In this context, marketing experts can use our results to adapt current offerings and delivery services, and better tailor them to individual preferences. The findings suggest that older, and hence more vulnerable, population segments should be specifically addressed, as these can benefit the most of grocery deliveries, and are yet those who adopt it the least. From a transport perspective, the increasing trend of online grocery shopping will translate into increasing number of delivery trips. As observable in many cities around the globe, these trips are often done using slow modes like electrified bicycles, scooters, or similar vehicles specialized for delivery. Transport regulators need to evaluate whether these patterns are desired and efficient, and whether the current infrastructure supports this shift. Finally, multiple statistical effects as well as derived indicators like the VSL suggest that the Swiss population is not as concerned with the infection risk as one would have thought. This supports the governmental strategy of applying substantially less strict measures than compared to other European countries, and provides a scientific basis for future similar situations.

All the generated insights, however, need to be assessed carefully when used for actual policy and product/service design. Apart from the methodological limitations like potential hypothetical bias, strategic behavior and anchoring effects that might lead to indicators that deviate from the actual (”true”) values (e.g., Hultkrantz and Svensson, 2012, Fosgerau et al., 2010), the collected data do not allow for drawing conclusions on how behavior might change again after the pandemic can be considered over. Whether COVID-19 had a persistent effect on online grocery shopping adoption in Switzerland requires further empirical work, especially to disentangle the pandemic effects from the general trend of increasing adoption.

Footnotes

Note that if a pandemic interaction effect was not significant/excluded, it was excluded from the model. This also holds for the (interaction) effects of socio-demographic and choice-set specific characteristics.

Note that the MIXL model would yield similar results as the ICLV model.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Hypothetical pandemic scenarios with varying spreading.

| scenarios | low: sporadic cases | moderate: clusters of cases | high: community transmission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reported infections | 4,000 | 80,000 | 200,000 | ||

| reported recoveries | 500 | 4,000 | 80,000 | ||

| risk of infection | 0.1% | 1% | 5% |

Table A2.

Probabilities for COVID-19 courses of varying severity.

| course | symptoms | probability |

|---|---|---|

| asymptomatic | none | 80% |

| mild course | (including influenza-like symptoms like cough, fever, fatigue, headache, as well as mild pneumonia) | 15% |

| critical course | (including severe pneumonia, respiratory failure and septic shocks) | 4.85% |

| fatal course | death | 0.15% |

Table A3.

Shopping costs (in-store/online).

| basket size | levels (in-store/online) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| () | () | ||

| small [CHF] | 36 / 32 | 40 / 36 | 44 / 40 |

| medium [CHF] | 72 / 65 | 80 / 72 | 88 / 79 |

| large [CHF] | 108 / 97 | 120 / 108 | 132 / 119 |

Table A4.

Shopping times (in-store/online).

| basket size | levels (in-store/online) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| () | () | ||

| small [min] | 10 / 5 | 15 / 10 | 20 / 15 |

| medium [min] | 25 / 20 | 30 / 25 | 35 / 30 |

| large [min] | 45 / 40 | 50 / 45 | 55 / 50 |

Table A5.

Attitudinal items, shopping.

| shop1 | I often shop for products online (+) |

| shop2 | Online shopping is associated with risk (-) |

| shop3 | Credit card fraud is one of the reasons why I do not like to shop online (-) |

| shop4 | The internet has more disadvantages than advantages (-) |

| shop5 | A disadvantage of online shopping is that I cannot physically inspect the products (-) |

| shop6 | Online shopping facilitates the comparison of products and prices (+) |

| shop7 | Receiving the wrong product is one of the reasons why I do not like online shopping (-) |

| shop8 | I like to follow the latest technological developments (+) |

| shop9 | I find everything that I need in physical shops (-) |

Table A6.

Attitudinal items, risk.

| risk1 | Would you drink more than five alcoholic drinks during one evening? (+) | |

|---|---|---|

| risk2 | Would you have unprotected intercourse with a stranger? (+) | |

| risk3 | Would you not wear your seat belt as sidecar passenger? (+) | |

| risk4 | Would you drive a motorbike without wearing a helmet? (+) | |

| risk5 | Would you expose yourself to the sun without using sun screen? (+) | |

| risk6 | Would you walk home alone at night through an unsafe part of town? (+) |

Table A7.

Travel costs (in-store).

| transport mode | levels |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| () | () | ||

| bike/foot [CHF] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| public transport (with local subscription) [CHF] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| public transport [CHF] | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| motorized individual transport [CHF] | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 |

Table A8.

Travel times (in-store).

| transport mode | levels |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| () | |||

| bike/foot [min] | 7 | 10 | 13 |

| public transport [min] | 6 | 9 | 12 |

| motorized individual transport [min] | 5 | 8 | 11 |

Table A9.

Descriptive analysis of sample compared to the Swiss MTMC.

| variable | value | % MTMC | % dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| age | 20-29 years | 11.3 | 18.5 |

| * | 30-39 years | 14.6 | 17.8 |

| 40-49 years | 19.7 | 17.7 | |

| * | 50-59 years | 20.1 | 18.0 |

| * | 60-69 years | 16.4 | 18.8 |

| * | 70-79 years | 12.3 | 7.9 |

| * | over 80 years | 5.2 | 1.0 |

| gender | female | 48.2 | 50.5 |

| * | male | 51.7 | 48.9 |

| * | other | - | 0.4 |

| education | compulsory education | 14.9 | 4.7 |

| * | further education | 52.0 | 67.3 |

| * | university | 33.0 | 27.8 |

| occupation | employed | 63.6 | 60.2 |

| * | student/apprentice | 2.8 | 5.0 |

| * | unemployed/household duties | 30.5 | 11.0 |

| * | searching for job | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| * | retired | 2.2 | 17.6 |

| household size | 1 | 15.3 | 29.3 |

| * | 2 | 33.7 | 36.0 |

| * | ⩾3 | 50.9 | 34.5 |

| household income | under 2,000 CHF | 1.5 | 7.0 |

| 2,001 - 4,000 CHF | 9.6 | 18.0 | |

| 4,001 - 6,000 CHF | 14.1 | 25.2 | |

| 6,001 - 8,000 CHF | 13.6 | 20.1 | |

| 8,001 - 10,000 CHF | 10.7 | 12.6 | |

| 10,001 - 16,000 CHF | 15.6 | 14.3 | |

| more than 16,000 CHF | 5.4 | 2.6 | |

| not provided | 29.0 | - | |

| citizenship | swiss | - | 90.0 |

| other | - | 9.9 | |

| online shopping behavior | never | - | 61.9 |

| once per week | - | 8.4 | |

| multiple times per week | - | 1.6 | |

| 2-3 times per month | - | 7.9 | |

| once a month or less | - | 19.9 | |

| shopping transport mode | PT | - | 23.6 |

| car | - | 42.2 | |

| foot/bike | - | 34.0 | |

| SARS-COV-2 infection | yes, tested positive | - | 1.2 |

| probably yes | - | 2.9 | |

| I don’t know | - | 26.8 | |

| probably no | - | 68.6 | |

| choices (pandemic, ) | in-store | - | 75.6 |

| online | - | 24.3 | |

| choices (pandemic, ) | with GOS experience | - | 38.0 |

| in-store | - | 65.8 | |

| * | online | - | 34.1 |

| * | without GOS experience | - | 61.9 |

| * | in-store | - | 81.6 |

| * | online | - | 18.3 |

| choices (regular, ) | in-store | - | 88.6 |

| * | online | - | 11.4 |

| choices (regular, ) | with GOS experience | - | 38.0 |

| in-store | - | 79.3 | |

| online | - | 20.6 | |

| without GOS experience | - | 61.9 | |

| in-store | - | 94.3 | |

| online | - | 5.6 | |

Table A10.

Estimation results for the MNL model specifications.

| Reference alternative: In-store shopping (S) | Coef. | Coef. | Coef. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated parameters | 10 | 22 | 50 |

| Respondents | 1009 | 1009 | 1009 |

| Choice observations | 8072 | 8072 | 8072 |

| LL(null) | -5082.75 | -5082.75 | -5082.75 |

| LL(choicemodel) | -3376.68 | -3339.25 | -3212.16 |

| AICc(choicemodel) | 6773.57 | 6723.53 | 6529.64 |

, , .

Note: Shopping and delivery cost are scaled down by factor 100.

Note: Waiting time is scaled down by factor 60, delivery time by factor 24.

References

- Allon G., Federgruen A., Pierson M. How much is a reduction of your customers’ wait worth? An empirical study of the fast-food drive-thru industry based on structural estimation methods. Manuf. Service Operations Management. 2011;13(4):489–507. [Google Scholar]

- ARE (2019) Value of statistical life (vosl): Empfohlener Wert der Zahlungsbereitschaft fuer die Verminderung des Unfall- und Gesundheitsrisikos in der Schweiz, Technical Report, Bundesamt fuer Raumentwicklung.

- BAG (2020) Situationsbericht zur epidemiologischen Lage in der Schweiz und im Fuerstentum Liechtenstein (08. Juni 2020), Technical Report, Bundesamt fuer Gesundheit.

- Ben-Akiva, M., J. Walker, A. Bernardino, D. Gopinath, T. Morikawa and A. Polydoropoulou (2002) Integration of choice and latent variable models, Perpetual Motion: Travel Behaviour Research Opportunities and Application Challenges, 431-470.

- Bezirgani A., Lachapelle U. Online grocery shopping for the elderly in Quebec, Canada: The role of mobility impediments and past online shopping experience. Travel Behaviour Soc. 2021;25:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat C., Dubey S. A new estimation approach to integrate latent psychological constructs in choice modeling. Transp. Res. Part B: Methodological. 2014;67:68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Blais A.-R., Weber E.U. A domain-specific risk-taking (dospert) scale for adult populations. Judgment Decision making. 2006;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Bouscasse, H. (2018) Integrated choice and latent variable models: A literature review on mode choice, Working Papers, Grenoble Applied Economics Laboratory (GAEL).

- Chang H.-H., Meyerhoefer C. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Covid-19 and the demand for online food shopping services: Empirical evidence from Taiwan. Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- ChoiceMetrics (2014) Ngene 1.1.2 user manual: The Cutting Edge in Experimental Design, Choice Metrics.

- Chorus C., Sandorf E.D., Mouter N. Diabolical dilemmas of Covid-19: An empirical study into Dutch societys trade-offs between health impacts and other effects of the lockdown. Plos one. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaço, R. and J. d. A. e Silva (2022) Exploring the e-shopping geography of Lisbon: Assessing online shopping adoption for retail purchases and food deliveries using a 7-day shopping survey, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65,102859.

- Czajkowski M., Budzinski W. Simulation error in maximum likelihood estimation of discrete choice models. J. Choice Modelling. 2019;31:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- de Bekker-Grob E.W., Ryan M., Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–172. doi: 10.1002/hec.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias, F.F., P.S. Lavieri, C.R. Bhat, R.M. Pendyala and W.H. Lam (2019) The interplay between virtual and in-person activity engagement: The case of shopping and eating meals, paper presented at the International Choice Modelling Conference 2019.

- Farag S. Utrecht University; 2006. E-shopping and its interactions with in-store shopping. [Google Scholar]

- Farag S., Dijst M., Lanzendorf M. Exploring the use of e-shopping and its impact on personal travel behavior in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003;1858(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar S., Ryan M. Response-ordering effects: a methodological issue in conjoint analysis. Health Econ. 1999;8(1):75–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199902)8:1<75::aid-hec400>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDHA (2020) Coronavirus: Federal council declares ’extraordinary situation’ and introduces more stringent measures, www.edi.admin.ch/edi/en/home/dokumentation/ medienmittei iunen html.msg-id-78 454. htm.

- Fosgerau M., Hjorth K., Lyk-Jensen S.V. Between-mode-differences in the value of travel time: Self-selection or strategic behaviour? Transp. Res. Part D: Transport Environ. 2010;15(7):370–381. [Google Scholar]

- Grashuis J., Skevas T., Segovia M.S. Grocery shopping preferences during the Covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2020;12(13):53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Greene W.H., Hensher D.A., Rose J. Accounting for heterogeneity in the variance of unobserved effects in mixed logit models. Transp. Res. Part B: Methodological. 2006;40(1):75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L.A., Arellana J., Oviedo D., Aristizábal C.A.M. COVID-19, activity and mobility patterns in Bogotá. Are we ready for a 15-minute city? Travel Behaviour and Society. 2021;24:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher D. A practical note on calculating a behaviourally meaningful generalised cost when there are two cost parameters in a utility expression. Road Transport Res. 2011;20(3):74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hess S., Beharry-Borg N. Accounting for latent attitudes in willingness-to-pay studies: the case of coastal water quality improvements in Tobago. Environ. Resource Econ. 2011;52(1):109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hole A.R. A comparison of approaches to estimating confidence intervals for willingness to pay measures. Health Econ. 2007;16(8):827–840. doi: 10.1002/hec.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao M.-H. Shopping mode choice: Physical store shopping versus e-shopping. Transp. Res. Part E: Logistics Transp. Rev. 2009;45(1):86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hultkrantz L., Svensson M. The value of a statistical life in Sweden: A review of the empirical literature. Health Policy. 2012;108(2–3):302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløjgaard M.E., Hess S. Understanding the formation and influence of attitudes in patients’ treatment choices for lower back pain: Testing the benefits of a hybrid choice model approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;114:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, W.F. (2010) Marketing research methods in SAS: Experimental design, choice, conjoint, and graphical techniques, SAS 9.2 Edition, MR 2010.

- Marcucci E., Gatta V., Le Pira M., Chao T., Li S. Bricks or clicks? consumer channel choice and its transport and environmental implications for the grocery market in norway. Cities. 2021;110 [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtarian P.L. A conceptual analysis of the transportation impacts of b2c e-commerce. Transportation. 2004;31(3):257–284. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy J., Schmid B., Becker F., Axhausen K.W. Institute for Transport Planning and Systems (IVT) ETH Zurich; Zurich: 2019. mixl: An open-source R package for estimating complex choice models on large datasets, Working Paper, 1408. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, N.B., I. Aksamentov, V. Druelle, A. Badenhorst, B. Ronzani, G. Jefferies, J. Albert and R. Neher (2020) Covid-19 scenarios: an interactive tool to explore the spread and associated morbidity and mortality of Sars-cov-2.

- Pawar D.S., Yadav A.K., Choudhary P., Velaga N.R. Modelling work-and non-workbased trip patterns during transition to lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic in India. Travel Behaviour and Society. 2021;24:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tbs.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R.A., Balasubramanian S., Bronnenberg B.J. Exploring the implications of the internet for consumer marketing. J. Acad. Marketing Sci. 1997;25(4):329. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz M.M., Ivanov D., Dolgui A., Wamba S.F. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: mapping a research agenda amid the Covid-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, K., K. Karthick and M.S. Kumar (2011) Online shopping in the UK, International Business & Economics Research Journal, 10 (12) 23–36.

- Revelt, D. and K. Train (2000) Customer-specific taste parameters and Mixed Logit: Households’ choice of electricity supplier, Working Paper, University of Berkeley, California.

- Rose J.M., Bliemer M.C.J. Constructing efficient stated choice experimental designs. Transp. Rev. 2009;29(5):587–617. [Google Scholar]

- Rossolov A., Rossolova H., Holguín-Veras J. Online and in-store purchase behavior: shopping channel choice in a developing economy. Transportation. 2021;48(6):3143–3179. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, T., O. Emrich, T. Böttger, K. Kleinlercher and T. Pfrang (2015) Der Schweizer Online-Handel: Internetnutzung Schweiz 2015, Universität St Gallen, Forschungszentrum für Handelsmanagement.

- Schmid, B. (2019) Connecting time-use, travel and shopping behavior: Results of a multi-stage household survey, Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich.

- Schmid B., Aschauer F., Jokubauskaite S., Peer S., Hössinger R., Gerike R., Jara-Diaz S.R., Axhausen K.W. A pooled RP/SP mode, route and destination choice model to investigate mode and user-type effects in the value of travel time savings. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Practice. 2019;124:262–294. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B., Axhausen K.W. In-store or online shopping of search and experience goods: A hybrid choice approach. J. Choice Modelling. 2019;31:156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B., Becker F., Molloy J., Axhausen K.W., Lüdering J., Hagen J., Blome A. Modeling train route decisions during track works. J. Rail Transport Planning Manage. 2022;22 [Google Scholar]

- Suel E., Polak J.W. Development of joint models for channel, store, and travel mode choice: Grocery shopping in London. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Practice. 2017;99:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Suel E., Polak J.W. Incorporating online shopping into travel demand modelling: challenges, progress, and opportunities. Transport Reviews. 2018;38(5):576–601. [Google Scholar]

- Swissinfo.ch (2020) Are the latest Swiss measures enough to fight the second covid wave?, www.swissinfo.ch/eng/are-the-latest-swiss-measures/: enough-to-fight-the-second-covid-wave-146135900.

- Te Grotenhuis M., Pelzer B., Eisinga R., Nieuwenhuis R., Schmidt-Catran A., Konig R. When size matters: advantages of weighted effect coding in observational studies. Int. J. Public Health. 2017;62(1):163–167. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0901-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Train, K. (2009) Discrete Choice Methods With Simulation, vol. 2009.

- Verity R., Okell L., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Thompson H., Walker P., Fu H., Dighe A., Griffin J., Baguelin M., Bhatia S., Boonyasiri A., Cori A., Cucunuba Z.M., FitzJohn R., Gaythorpe K., Ferguson N. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij A., Walker J.L. How, when and why integrated choice and latent variable models are latently useful. Transp. Res. Part B: Methodological. 2016;90:192–217. [Google Scholar]

- VSV (2020) Medienmitteilung, https://wWW.vsv-versandhandel.ch/:wp-content/uploads/2020/03/DE-2020.03.11-Medienmitteilung -VSV-GeK_Online_und_Versandhandel-2019.pdf.

- Walker J., Ben-Akiva M. Generalized random utility model. Math. Social Sci. 2002;43(3):303–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wang E., An N., Gao Z., Kiprop E., Geng X. Consumer food stockpiling behavior and willingness to pay for food reserves in Covid-19. Food Security. 2020;12(4):739–747. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01092-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.C., Kim W., Holguín-Veras J., Schmid J. Adoption of delivery services in light of the covid pandemic: Who and how long? Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Practice. 2021;154:270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann R., Boes S. Springer Science and Business Media; Berlin Heidelberg: 2006. Analysis of Microdata. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans, K.A. and P.A. Golder (1982) The Guttman-Kaiser criterion as a predictor of the number of common factors, The Statistician, 221–229.

- Zhai Q., Cao X., Mokhtarian P.L., Zhen F. The interactions between e-shopping and store shopping in the shopping process for search goods and experience goods. Transportation. 2017;44(5):885–904. [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein, D. and C. Oswald (2020) Onlinehändlerbefragung 2020: nachhaltiges Wachstum des E-Commerce und Herausforderungen in Krisenzeiten, Technical Report, ZHAW Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften.