Abstract

Effective models focused on pertinent low-energy degrees of freedom have substantially contributed to our qualitative understanding of quantum materials. An iconic example, the Kondo model, was key to demonstrating that the rich phase diagrams of correlated metals originate from the interplay of localized and itinerant electrons. Modern electronic structure calculations suggest that to achieve quantitative material-specific models, accurate consideration of the crystal field and spin-orbit interactions is imperative. This poses the question of how local high-energy degrees of freedom become incorporated into a collective electronic state. Here, we use resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (RIXS) on CePd3 to clarify the fate of all relevant energy scales. We find that even spin-orbit excited states acquire pronounced momentum-dependence at low temperature—the telltale sign of hybridization with the underlying metallic state. Our results demonstrate how localized electronic degrees of freedom endow correlated metals with new properties, which is critical for a microscopic understanding of superconducting, electronic nematic, and topological states.

Subject terms: Electronic properties and materials, Magnetic properties and materials, Electronic structure

The fate of high-energy degrees of freedom, such as spin-orbit interactions, in the coherent state of Kondo lattice materials remains unclear. Here, the authors use resonant inelastic x-ray scattering in CePd3 to show how Kondo-quasiparticle excitations are renormalized and develop a pronounced momentum dependence, while maintaining a largely unchanged spin-orbit gap.

Introduction

Metals containing lanthanides are optimally suited to study the Kondo lattice problem, owing to highly localized 4f-electrons, which at low temperature form a strongly-correlated many-body state1,2. The Kondo lattice model is characterized by two effective low-energy scales3 (see Fig. 1a–c): the Kondo temperature TK, below which local f-electron magnetic moments become effectively coupled to the surrounding conduction electrons, and the coherence temperature Tcoh, below which these states are coherently incorporated into the underlying band structure as dispersive, albeit heavy, electronic quasiparticles. A large body of experiments has shown that real materials can indeed be qualitatively characterized by these two energy scales. Modern angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)4, quasiparticle interference5, and inelastic neutron scattering (INS)6 have even directly observed the formation of coherent heavy quasiparticle bands. Frustrated magnetism7, unconventional superconductivity8, hidden order9, as well as topologically non-trivial10–12 and electronic-nematic states13,14 are all known to emerge from this Kondo lattice state.

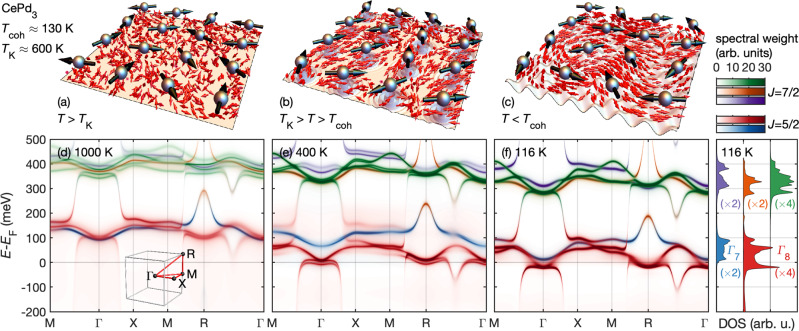

Fig. 1. Emergence of a coherent Kondo lattice state as a function of temperature in CePd3.

a–c Real-space impressions of the increasingly coherent screening of Ce moments (black arrows) across the temperature scales TK and Tcoh. Spins of itinerant electrons are represented by red arrows (see text for details). d–f Electronic spectral function A(k, ω) of CePd3 obtained from the combination of density functional and dynamical mean field theory (DFT+DMFT) at 1000 K, 400 K, and 116 K. The fourteen 4f orbitals of cerium form seven Kramers doublets, separated into a J = 5/2 sextuplet and a J = 7/2 octuplet by ESO ≈ 280 meV. A cubic crystal field (CF) further induces a ESO ≈ 10 meV splitting between a J = 5/2Γ7 doublet (blue) and the Γ8 quartet (red). The J = 7/2 states are split into two doublets (purple and orange) and one quartet (green). a, d Above the Kondo temperature, TK ≈ 600 K, local f-electron moments are uncorrelated. The corresponding electronic structure only shows weak hybridization with the incoherent f-states. b, e For T < TK, local f-electron magnetic moments effectively couple to the surrounding conduction electrons, forming virtual-bound states in the vicinity of the Fermi energy EF (suggested as ripples in b). The f spectral weight close to the Fermi surface remains predominantly incoherent. c, f Below the coherence temperature Tcoh ≈ 130 K, the f-states are coherently incorporated (suggested by the lattice-coherent modulation in Panel c) into the underlying band structure as dispersive, albeit heavy, electronic quasiparticles. The right panel shows the density of states (DOS) summed over the displayed high-symmetry directions, projected onto the different CF characters.

The two phenomenological energy scales (TK, Tcoh) clearly do not suffice to account for this variety of experimental discoveries. Instead, material-specific knowledge of the quasiparticle fine structure will be required to disentangle the underlying interaction channels and achieve a guided design of emergent functional properties. Magnetic, thermodynamic15, and X-ray spectroscopic16 studies of crystal-field (CF) ground states in Kondo lattices have indeed demonstrated that the anisotropic hybridization of the f-electron wave function strongly influences the ground state properties, even for materials with the same crystal structure. Moreover, bulk measurements as a function of external tuning parameters like magnetotransport and magnetostriction suggest that the structure of unoccupied crystal field levels cannot be disregarded in these investigations17,18. Realistic models of these circumstances can be achieved by the combination of density functional and dynamical mean field theory (DFT+DMFT). And indeed, such calculations have recently confirmed that high energy scales like CF and SO splitting must be taken into account to quantitatively reproduce low-energy ground states4,19,20.

Clarifying the mechanisms by which the properties of localized f-electrons blend into an itinerant environment is an outstanding experimental challenge. While local probes capture the overall energy scales of CF and SO excited states, they cannot observe their momentum dependence—the telltale sign of hybridization with the underlying metallic state. This crucial microscopic knowledge requires low-energy momentum-resolved spectroscopic methods like quasiparticle interference or INS. Recent pioneering ARPES studies4,21,22 have directly mapped anisotropic hybridization close to the Fermi energy in CeMIn5 and CeM2X2 heavy fermion materials (M = transition metal; X = Si, Ge). This new level of material-specific microscopic insights has shone a light on the relevance of crystal field and magnetic degrees of freedom, and has called into question widely accepted concepts like the direct relation between the temperature scale Tcoh and the formation a “large” Fermi surface22. One common constraint of these techniques is that they lack sensitivity to the unoccupied f-electronic structure at higher energies23. To overcome this limitation, we take advantage of instrumental advances that have made resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) a powerful probe of Kondo lattices24,25.

M-edge RIXS is a photon-in/photon-out process in which 3d core electrons are resonantly excited and recombine by dipole-transitions after interacting with 4f valence states. Like INS, this serves as a probe of two-particle correlations, providing a complementary perspective on the single-particle spectral function measured by ARPES. It has the advantage of true bulk-sensitivity at good energy resolution, but, in contrast to INS, the observation of inter-/intraband transitions by X-rays is not restricted to the spin-flip channel. RIXS also has major experimental advantages, as it is not dominated by phonon scattering, and does not require large single crystals and long counting times. Crucially for the present context, the insights are neither limited by the instrumental energy resolution, nor in the range of energy transfer, and the resonant character and polarization dependence allow to separate different excitation channels25.

We focus on the archetypal Kondo lattice material CePd3, with an effective f-occupation of nf ≈ 0.75 (from X-ray absorption spectroscopy26), and kBTK ≈ 55 meV. The Kondo energy of this system is thus intermediate to the bare SO coupling ESO ≈ 280 meV of Ce and the coherence energy scale kBTcoh ≈ 11 meV (derived from transport data)27 and CF splitting ECF ≈ 10 meV (from comparison to the isostructural material CeIn328 and the present DFT calculation). This cascade of energy scales makes CePd3 ideally suited to address both our experimental and computational objectives, i.e., to understand how crystal field and spin-orbit interactions become coherently incorporated into the Kondo lattice state. The relatively large Tcoh and TK ensure that temperatures accessible by DFT+DMFT are sufficient to simulate coherence6, and the quasiparticle bandwidth is large compared to the energy resolution dE ~ 35 meV of RIXS.

Results

Figure 1 shows the correlated band structure of CePd3 at 1000 K, 400 K, and 116 K, as obtained via DFT+DMFT calculations to visualize the emergence of a coherent Kondo lattice in CePd3. Cerium features fourteen 4f orbitals corresponding to seven Kramers doublets, separated into a J = 5/2 sextuplet and a J = 7/2 octuplet by ESO. The cubic CF further splits the J = 5/2 and J = 7/2 states into a total of five CF multiplets indicated in Fig. 1 in distinct colors. Figure 1d illustrates that even at T = 1000 K > TK, the modulation of the 4f states due to the onset of anisotropic hybridization outweighs the weak CF splitting, which underscores the importance of momentum-resolved data. Below TK ≈ 600 K, the increasing hybridization renormalizes all 4f-states. However, their spectral weight close to the Fermi surface remains predominantly incoherent (Fig. 1e). For T < Tcoh ≈ 130 K, coherence sets in, and well-defined quasiparticle bands that cross the Fermi level form pockets at the Γ and R points (Fig. 1f). Our calculations emphasize the amount of information encoded in the unoccupied states. Instead of the Γ7 CF ground state of isostructural (and more localized) CeIn329, we find that the hybridization with Pd d bands endows the quasiparticle pockets with Γ8-like character akin to CeB630 (for CePd3 at 116 K we obtain occupation numbers nΓ7 = 0.08 and nΓ8 = 0.68). The SO excited states are similarly modified due to hybridization. Figure 1f shows the summed density of states of different orbital characters. We find that the J = 7/2-like states retain an occupation number of 0.17, even at low temperatures (116 K). This indicates that, aside from the mixing of CF states, strictly speaking, even J cannot be considered a good quantum number (EK ≈ 0.2 ESO).

Recently, Goremychkin et al.6 used state-of-the-art DFT+DMFT calculations, like those presented here, to quantitatively model their neutron spectra of magnetic inter-band transitions and conclusively demonstrate the formation of coherent quasiparticle bands in CePd3. This pioneering work has raised several remaining key issues on the nature of the coherent state: (i) To date, the phenomenological temperature scale Tcoh has only been inferred from bulk properties like maxima in resistivity and magnetic susceptibility27 and the onset of phase-coherence remains to be explored microscopically. (ii) The INS study6 was limited to energy transfers between 20 and 65 meV, but also predicted excitations within the putative SO gap, which calls into question how coherence impacts the coupling of spin and orbital momentum. (iii) To clarify the fate of CF ground states assigned to heavier Ce systems, it would be crucial to resolve the fine structure of the quasiparticle bands.

To address these challenges, our study has to overcome the limitations of INS as a probe of electronic structure and encompass all energy scales relevant for DFT+DMFT. To complement RIXS, we present first single-crystal ARPES data of CePd3, resolving electronic structure within few meV of the Fermi level. Moreover, we corroborate the two-particle dynamics in the 50–250 meV regime by higher-energy INS (see Section 3 of the Supplementary Information (SI)31 file), and use X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to probe the RIXS intermediate states in the presence of a Ce 3d5/2 core hole. This provides fixed points for a global, realistic model of the inter-band transitions.

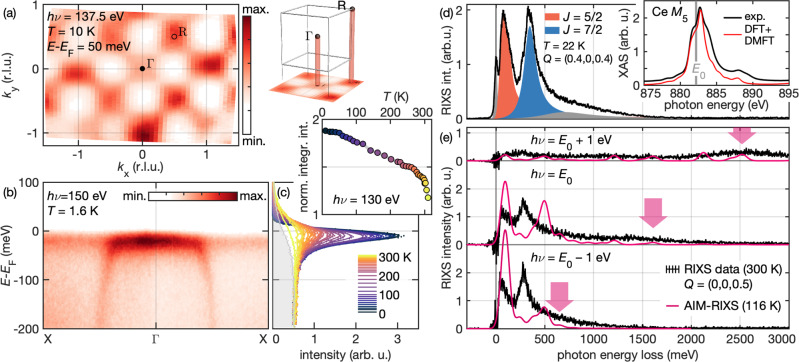

Figure 2a, b shows the occupied quasiparticle states in the vicinity of the Fermi level of a [1, 0, 0]-fractured sample at low temperatures obtained via single-crystal vacuum ultraviolet ARPES measurements. As predicted by DFT+DMFT, quasiparticle Fermi pockets form at the Γ and R points. Since the electron momentum perpendicular to the sample surface (kz) is not resolved in these measurements, both Γ and R hot spots are projected onto the kx–ky plane. The observed characteristic checkerboard-pattern of the dispersion around the Γ point confirm that DFT+DMFT yields an adequate model of the coherent Kondo lattice state with regard to the quasiparticles below the Fermi energy. Figure 2c illustrates how spectral weight due to increasing hybridization of f-states continuously rises at low temperatures and forms a ~30 meV wide Kondo peak at the Fermi surface, which is closely reminiscent of Fig. 1d–f.

Fig. 2. Comparison of our model with spectroscopic data, covering the electronic structure of CePd3 from the meV to the eV scale.

For a global comparison of the DFT+DMFT calculation with the prototypical Kondo lattice material, we employ three spectroscopic methods. a–c Vacuum ultraviolet angle-resolved photo emission spectroscopy (ARPES) reveals the electronic spectral function A(k, ω) with meV resolution. a Low-temperature quasiparticle Fermi surface observed by ARPES. As the momentum along the surface normal is not resolved, the pockets Γ and R are projected onto the kx–ky plane (cf. illustration of the Brillouin zone). b High-resolution ARPES spectrum highlighting the hybridization of the almost vertical Pd 4d bands with the Ce 4f states at the Γ point. c Temperature dependence of energy distribution curves of this Kondo resonance. The gray shaded area is the reference spectrum of a gold foil at 310 K. The inset shows the integrated intensity of f-electronic density of states normalized to the integrated intensity of the metallic background, as approximated by the gold spectrum. d, e Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) covering energy transfers of several eV. d Overview of the characteristic features of CePd3 RIXS at E0 = 882.2 eV, here shown for Q = (0.4, 0, 0.4), at 22 K. Spectral weight assigned to excitations of either spin orbit state is marked by colored Lorentzian lineshapes. The resolution-limited elastic peak and a sloping background due to excitations into the continuum of Pd 4d states are shaded gray. The inset shows a comparison of the low-temperature Ce M5 X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) spectrum with our DFT+DMFT calculation. e Comparison of a Q = (0, 0, 0.5) RIXS spectrum at E0 with data recorded 1 eV above/below this resonance (elastic line subtracted). Pink lines show the respective results of the AIM-RIXS calculation at 116 K. Aside from the Raman-like J = 5/2 and J = 7/2 peaks, the calculation captures the shift of continuum excitations to higher energy transfers at higher photon energies hν (indicated by arrows). Due to the necessarily coarse discretization, the SO gap is consistently overestimated and the continuum is mapped onto a series of peaks.

Now we turn to discuss our RIXS measurements. Figure 2d shows a typical M5 RIXS spectrum of CePd3, recorded at 22 K (i.e., well below the coherence temperature), at a photon energy of E0 = 882.2 eV, where excitations of f-quasiparticles with J = 5/2 and J = 7/2-like character carry similar spectral weight (as indicated by phenomenological colored Lorentzian line shapes). The two SO bands are much wider than the instrumental energy resolution, which can be inferred from the elastic line, a Gaussian peak of 32 meV full-width at half-maximum. Their intensity appears in the crossed () polarization channel and is likely of magnetic character (see Supplementary Note 631). We find no additional two-particle excitation in the ~200 meV regime. Instead, up to this energy, RIXS is in quantitative agreement with the dynamic magnetic susceptibility χ″(Q, ω) probed by INS (see our detailed discussion in Supplementary Note 331). However, neutron excitations across the spin-orbit gap are suppressed by a factor ~200 23, which makes it de facto impossible to probe momentum dependence of excited f-electron states with INS. As a combination of two consecutive dipole transitions, RIXS breaks free of these constraints. Moreover, by selecting the intermediate state and using polarization analysis, it is possible to separate the J = 5/2 and J = 7/2 RIXS spectral weight31.

For a realistic model of RIXS in CePd3 going beyond the comparison to INS, we compute the Kramers-Heisenberg cross section in an Anderson impurity model based on the DFT+DMFT electronic structure31. Notably, this AIM-RIXS calculation relies on a single parameter, the double-counting correction μdc, which shifts the energy of the 4f states to take into account the f−f interaction present in the DFT calculation. The value of μdc was chosen to reproduce the XAS characteristics, shown in the inset to Fig. 2d, and the density of states observed in direct and inverse photoemission31. It is further corroborated by the favorable comparison with ARPES. We thus achieve a reliable model of the electronic structure spanning three orders of magnitude in energy, from the f−f interaction (Uff = 6 eV) down to the width of the occupied f-states at the Fermi surface (~30 meV) and CF splitting (10 meV).

The exact evaluation of the Kramers-Heisenberg term in the AIM comes at the price of losing the momentum-resolution and of discretizing the DFT+DMFT bath (we use a set of 20 levels31). Subtle aspects of the electronic structure, like an accurate reproduction of the renormalized spin-orbit gap are lost in this necessarily coarse model of local-itinerant hybridization. On the other hand, AIM-RIXS does capture the resonant creation of the excited states. In Fig. 2e, we compare calculated spectra with experimental data above and below the resonance at E0. Both quasiparticle excitations behave Raman-like, i.e., the energy transfer is independent of hν. Excitations of f-quasiparticles that escape into the wide Pd 4d bands contribute a fluorescence tail that shifts to higher energies at higher photon energies. This effect is well captured in Fig. 2d, even if the continuum is mapped onto a set of discrete peaks. Thorough discussions of the photon-energy dependence, polarization dependence, and XAS characteristics are provided in the SI31.

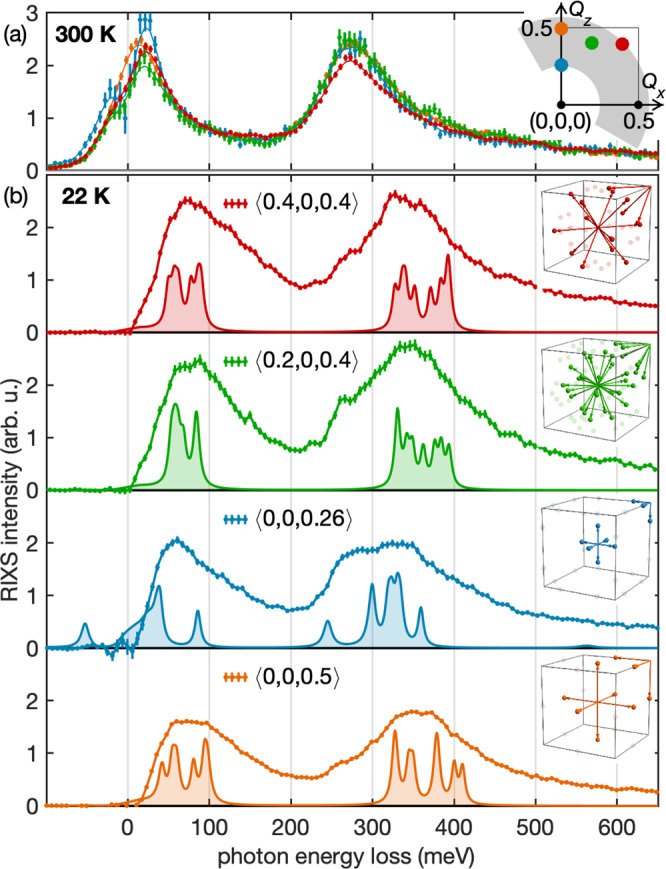

To probe the momentum-dependence of these f-states for T < Tcoh, as predicted in Fig. 1, we recorded RIXS spectra at four different points in the Brillouin zone, at 300 K and at 22 K. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, the response at T > Tcoh is close to isotropic. By contrast, the corresponding spectra in the lattice-coherent state [Fig. 3b] vary dramatically in both spectral weight and energy. Surprisingly, these observations are most pronounced among the spin-orbit excited quasiparticles, with a dispersion of ≈40 meV between Q = (0, 0, 0.26) and (0, 0, 0.5). In the absence of momentum-resolved RIXS calculations, it is instructive to relate these observations to the DFT+DMFT spectra. Because the occupied f-quasiparticles are constrained to narrow hot-spots at Γ and R, a simple argument can be made: For each of the investigated momentum transfers, symmetry-equivalent excitation paths within the Brillouin zone are illustrated in the insets to Fig. 3b. For instance, Q = (0, 0, 0.5) probes transitions (Γ → X, R → M), which should be comparable to Q = (0.5, 0, 0.5) (Γ → M, R → X). This is consistent with the observation of similar spectra at Q = (0, 0, 0.5) and Q = (0.4, 0, 0.4), and significant variations between Q = (0, 0, 0.26) and (0, 0, 0.5). For direct comparison, the sum of the 116 K DFT+DMFT density of states at the respectively relevant positions in the Brillouin zone is drawn as shaded line shapes in Fig. 3b. Despite EK ≫ ECF, RIXS is clearly able to resolve the fine structure of the hybridized spin-orbit multiplets.

Fig. 3. Fingerprint of a coherent Kondo lattice state in CePd3 as observed by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS).

RIXS spectra are shown at four different momentum transfers Q, at a 300 K and b 22 K. For better comparison, the quasielastic peak has been subtracted. The positions of Q are indicated in the reciprocal space map inset, where the Q range accessible to M5-edge RIXS is shaded gray. While at T = 300 K, well above the coherence temperature Tcoh ≈ 130 K, the signal is almost invariant with regard to Q, for T = 22 K a pronounced momentum-dependence emerges. The inset views of the cubic Brillouin zone in b illustrate how the Q positions probed with RIXS correspond to momentum transfers exciting heavy quasiparticles from electron pockets at Γ and R into unoccupied parts of the electronic structure. For reference, the shaded spectra in each panel show the DFT+DMFT density of states, as shown in Fig. 1c, summed over the relevant positions of quasiparticle momentum-transfers in the Brillouin zone.

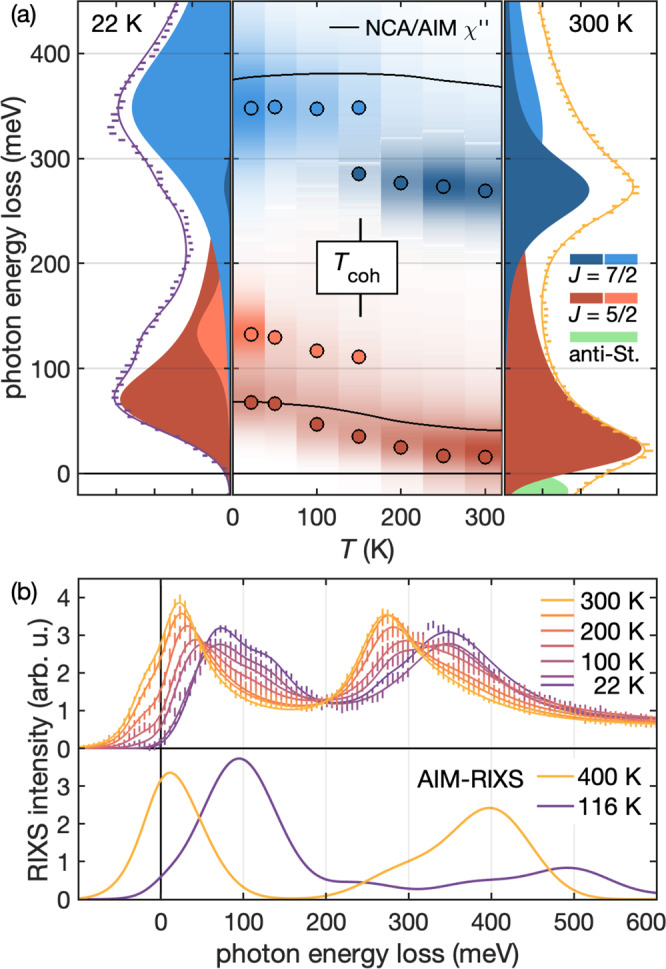

As shown in Fig. 4, the characteristics of the RIXS Kondo excitations change dramatically when thermal fluctuations destroy the lattice-coherence. Figure 4a shows spectra at momentum transfer Q = (0.4, 0, 0.4), at 22 K and at 300 K [left and right panels]. Colored lineshapes illustrate phenomenological fits of Lorentzian lineshapes (for better comparison with AIM-RIXS spectra, the elastic line has been subtracted). The center panel shows how, at low temperatures, both excitations continuously shift to higher energies. The black lines indicate the maxima of the momentum averaged dynamic magnetic susceptibility χ″(ω) of the Anderson impurity model in the non-crossing approximation (NCA/AIM, see Supplementary Note 131). It is thus evident that even phenomenological models reproduce the basic thermal trend of the J = 5/2 excitations. However, at intermediate temperatures, both J = 5/2 and 7/2 bands develop the momentum-dependent substructure discussed above, which corresponds to the onset of coherence. This microscopic observation of Tcoh ≈ 130 K is consistent with bulk methods27. Figure 4b shows that our AIM-RIXS approach does indeed capture the parallel thermal shift of both SO states by ≈ 80 meV. The apparent overestimation of the SO gap is due to the limited number of bath levels determined by computational cost, which does not allow to accurately capture the renormalization of J = 7/2 and 5/2 due to hybridization with conduction bands.

Fig. 4. Onset of coherence in CePd3 as observed by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS).

a Detailed thermal variation of RIXS spectra between 22 K and 300 K. For clarity, the elastic lines have been subtracted from the data. The emergence of the coherent state at Tcoh appears as a transfer of intensity between distinct excitations. We phenomenologically model this by Lorentzian fits of the data, as indicated in the left (22 K) and right (300 K) panels. Colored markers in the center panel indicate the centroids of these features. As the J = 5/2 quasiparticles become thermally populated, an anti-Stokes peak (green) appears on the photon-energy-gain side. The black lines show the thermal evolution of the J = 5/2 and J = 7/2 peaks in our NCA/AIM calculation of χ″ (see text for details). b Comparison of temperature-dependent RIXS (top) with the exact AIM-RIXS calculation (bottom). This model accurately captures the parallel shift of J = 5/2 and J = 7/2 features. The overestimation of the SO gap is an artifact of the necessary discretization (see text for details).

Discussion

Our study showcases that RIXS provides a comprehensive picture of the emergent coherent Kondo lattice state, enabling a detailed comparison with material-specific state-of-the-art band structure calculations on all relevant energy scales. Crucially, RIXS reveals the exact position of all f-electron levels and how they blend into the underlying metallic state. We have used this capability to clarify the characteristic energy scales of the model Kondo lattice material CePd3. The fine structure and momentum dependence of the observed spectra is consistent with the five CF multiplets inferred from our DFT+DMFT calculation [Fig. 1a]. Below the coherence temperature Tcoh ≈ 130 K, which we have determined microscopically, the hybridization with the conduction electrons impacts all f states on the scale of EK ≈ 55 meV. Even though the overall 80 meV renormalization of the J = 5/2 peak as a function of temperature in Fig. 4a amounts to 30% of the free-ion spin-orbit coupling (280 meV), the SO gap remains unchanged in the coherent Kondo lattice state. This implies that the strength of the SO interaction determined by L ⋅ S is not impacted by the substantial renormalization of the electronic state that is evidenced by overall shifts of the f-levels (cf. Fig. 4) and their variation throughout the Brillouin zone (cf. Fig. 1), both of which are on the order of EK. Interestingly, this observation is contrary to the interpretation by Murani et al.32, who expected that f band formation should lead to at least a partial quenching of orbital momentum and a reduction of L ⋅ S.

In conclusion, our study reveals in unprecedented detail how the full manifold of localized f-electron states becomes hybridized with the underlying band structure in the archetypal Kondo metal CePd3. Such insight is crucial for the development of fully microscopic and material-specific models of quantum-coherency and to understand how it drives the emergence of novel order parameters. The remarkable discovery that f-electron band formation below the coherence temperature does not quench the spin-orbit interaction showcases how—via the mechanism of hybridization—even excited f-electron states can endow a material with novel properties that cannot be derived simply from the symmetry of the underlying crystal lattice. This is key to a growing number of topical phenomena such as p-wave superconductivity, electronic-nematic order, and topologically non-trivial phases. Given that the present insights were not limited by the experimental energy resolution, similar studies are already feasible in materials with lower Kondo energy scales or in systems where Kondo dynamics can be tuned by external parameters. They can also be performed on microscopic single crystals not accessible to INS and will benefit from continuous improvements in brilliance and energy resolution33.

Methods

Samples

An ingot of cubic CePd3 (AuCu3 structure, space group , lattice parameter a = 4.13 Å) was grown from a self-contained melt using a modified Czochralski method in a tri-arc furnace. Single-crystalline grains were identified and oriented by backscattering Laue X-ray diffraction. Cuboid samples with faces parallel to [100] planes were then cut from this grain. Incisions were made around the circumference of these samples to favor fracturing parallel to these planes.

Photoemission spectroscopy

Vacuum ultraviolet angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy was performed at a BL5-2, SSRL (Stanford), beamline 4.0.3, ALS (Berkeley), and one-cube, BESSY-II (Berlin). The samples were fractured under ultra-high vacuum conditions of <5 × 10−11 Torr. The best contrast from the Ce 4f states was obtained above the N (4d → 4f) absorption edge, at photon energies of 130–150 eV. The electrons were analyzed using Scienta R8000 (4.0.3) and Scienta DA30L (BL5-2, one-cube) spectrometers.

X-ray spectroscopy

Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering experiments were carried out at endstation ID32-ERIXS, ESRF (Grenoble), with a combined energy resolution of 34 meV at the Ce M5 resonance (hν ≈ 882 eV)34. The samples were fractured in situ under ultra-high vacuum conditions. Data was collected in cycles of 5 min for 7–8 h per spectrum and processed using the RIXS Toolbox suite35. Data shown in the main text is measured with incident polarization in the scattering plane, without polarization analysis of the scattered beam. The polarization analysis of the scattered beam36 is demonstrated in Supplementary Note 631. Ce M edge X-ray absorption spectra were obtained during the RIXS experiment (total electron yield mode) and were confirmed by additional measurements in fluorescence yield mode measured at BL29/BOREAS, ALBA (Barcelona), see ref. 31.

Inelastic neutron scattering

Neutron time-of-flight neutron spectra of CePd3 were obtained on ARCS, SNS (Oak Ridge) at an incident energy of Ei = 400 meV. The same 20 g single crystal and experimental procedures were used as in ref. 6.

Computational models

The temperature evolution of the 2F5/2 and 2F7/2 excitations (Fig. 4a, black solid lines) was inferred by the momentum-averaged dynamic susceptibility χ″(ω) in the Anderson impurity model (AIM) computed with the non-crossing approximation37, as described in our earlier work38 and discussed in ref. 31. The NCA/AIM description assumes a single f-level (with large orbital degeneracy), a constant hybridization with a Gaussian shape (fixed width) of the conduction band.

The DFT+DMFT electronic structures of CePd3 shown in Fig. 1 were obtained using the Wien2K package39,40 and the strong-coupling continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo impurity solver41–44, details can be found in ref. 31. The cerium site energy was shifted by the double-counting term μdc, which corrects for the f–f interaction inherent in the LDA results. The μdc value was chosen to reproduce the experimental XAS [cf. Fig. 2d], as well as the electronic spectral function A(k, ω) observed in direct/inverse photoemission and ARPES data of CePd3, as illustrated in Figs. 1f and 2b and refs. 31, 45, 46. We employed a diagonalization solver with a configuration-interaction scheme for evaluating the RIXS intensities using the Kramers-Heisenberg term from the AIM with the DFT+DMFT hybridization densities (Fig. 2d, e). The AIM-RIXS calculations of the density of states, XAS and RIXS spectra were performed in analogy to our earlier work47 and are discussed in detail in ref. 31.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for provision of experimental time at beamline ID32 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), Grenoble, France, at beamline BL5-2 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) of the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, operated by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515, at beamline 4.0.3. of the Advanced Light Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231, at beamline UE112_PGM-2b-1^3 of the BESSY-II electron storage ring operated by the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie (HZB), at beamline BL29 of the ALBA Synchrotron, Spain, and at the ARCS spectrometer at the Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Work at Los Alamos National Laboratory was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering. M.C.R. is grateful for support through the LANL Director’s Fund and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. J.-X.Z. was supported by the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, a DOE BES user facility. J.K. was supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF) through QUAST-FOR5249 (project I 5868-N). A.H. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21K13884 and 21H01003. K.-H.A. was supported by the Czech Science Foundation Project Grant Number 19-06433S. A.D.C. was partially supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. A.A. acknowledges the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG under project SE1441/5-2. Work at TU Dresden was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the CRC 1143 and the Würzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat (EXC2147, Project ID 390858490). The work by F.H. and M.J. was supported through a Hans Fischer fellowship of the Technische Universität München-Institute for Advanced Study, funded by the German Excellence Initiative and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme under Grant agreement No. 291763. Special thanks are due to Daniel Mazzone, Johan Chang, Pascoal Pagliuso, Jason Hancock, and Peter Riseborough for insightful discussions.

Author contributions

M.C.R., M.J., F.R., and J.M.L. designed the research. M.C.R., E.B., D.D.B., and K.J.M. synthesized the samples. M.C.R. planned and conducted the RIXS and ARPES measurements, with assistance from M.J., A.A., and F.H.; K.K. and J.D.D. performed additional RIXS, XAS, and ARPES measurements. A.D.C. and J.M.L. planned and performed the neutron measurement. Instrument scientists K.K., J.D.D., D.-H.L., M.H., E.R., and M.V. enabled and assisted in experiments. A.H., J.K., K.-H.A., J.-X.Z., and C.H.B. performed calculations and advised on the theoretical interpretation of the data. M.C.R. analyzed the data. M.C.R. and M.J. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the OpARA database of TU Dresden under accession code 123456789/5706.

Code availability

All numerical codes in this paper are available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. C. Rahn, Email: marein.rahn@tu-dresden.de

M. Janoschek, Email: marc.janoschek@psi.ch

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-33468-6.

References

- 1.Paschen S, Si Q. Quantum phases driven by strong correlations. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021;3:9–26. doi: 10.1038/s42254-020-00262-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence JM. Intermediate valence metals. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 2008;22:1273–1295. doi: 10.1142/S0217984908016042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burdin S, Georges A, Grempel DR. Coherence scale of the Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:1048–1051. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang S, et al. Evolution of the Kondo lattice electronic structure above the transport coherence temperature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:23467–23476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001778117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aynajian P, et al. Visualizing heavy fermions emerging in a quantum critical Kondo lattice. Nature. 2012;486:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goremychkin EA, et al. Coherent band excitations in CePd3: a comparison of neutron scattering and ab initio theory. Science. 2018;359:186–191. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fobes DM, et al. Tunable emergent heterostructures in a prototypical correlated metal. Nat. Phys. 2018;14:456–460. doi: 10.1038/s41567-018-0060-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfleiderer C. Superconducting phases of f-electron compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009;81:1551–1624. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mydosh JA, Oppeneer PM, Riseborough PS. Hidden order and beyond: an experimental—theoretical overview of the multifaceted behavior of URu2Si2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2020;32:143002. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/ab5eba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirie H, et al. Imaging emergent heavy Dirac fermions of a topological Kondo insulator. Nat. Phys. 2020;16:52–56. doi: 10.1038/s41567-019-0700-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurumaji T, et al. Skyrmion lattice with a giant topological Hall effect in a frustrated triangular-lattice magnet. Science. 2019;365:914–918. doi: 10.1126/science.aau0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiao L, et al. Chiral superconductivity in heavy-fermion metal UTe2. Nature. 2020;579:523–527. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronning F, et al. Electronic in-plane symmetry breaking at field-tuned quantum criticality in CeRhIn5. Nature. 2017;548:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature23315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo S, et al. Nematic state in CeAuSb2. Phys. Rev. X. 2020;10:011035. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagliuso P, et al. Structurally tuned superconductivity in heavy-fermion CeMIn5 (M = Co, Ir, Rh) Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 2002;320:370–375. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4526(02)00751-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willers T, et al. Correlation between ground state and orbital anisotropy in heavy fermion materials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2384–2388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415657112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moll PJW, et al. Emergent magnetic anisotropy in the cubic heavy-fermion metal CeIn3. npj Quant. Mater. 2017;2:46. doi: 10.1038/s41535-017-0052-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosa PFS, et al. Enhanced hybridization sets the stage for electronic nematicity in CeRhIn5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;122:016402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.016402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shim JH, Haule K, Kotliar G. Modeling the localized-to-itinerant electronic transition in the heavy fermion system CeIrIn5. Science. 2007;318:1615–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.1149064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haule K, Yee C-H, Kim K. Dynamical mean-field theory within the full-potential methods: electronic structure of CeIrIn5, CeCoIn5, and CeRhIn5. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;81:195107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.195107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S, et al. Arpes view on surface and bulk hybridization phenomena in the antiferromagnetic kondo lattice CeRh2Si2. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11029. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kummer K, et al. Temperature-independent Fermi surface in the Kondo lattice YbRh2Si2. Phys. Rev. X. 2015;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murani AP, Raphel R, Bowden ZA, Eccleston RS. Kondo resonance energies in CePd3. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;53:8188–8191. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.53.8188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock JN, et al. Kondo lattice excitation observed using resonant inelastic x-ray scattering at the Yb M5 edge. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;98:075158. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.075158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amorese A, et al. Crystal electric field in CeRh2Si2 studied with high-resolution resonant inelastic soft x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:245130. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.245130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fanelli VR, et al. Q-dependence of the spin fluctuations in the intermediate valence compound CePd3. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2014;26:225602. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/26/22/225602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence JM, Thompson JD, Chen YY. Two energy scales in CePd3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985;54:2537–2540. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knafo W, et al. Study of low-energy magnetic excitations in single-crystalline CeIn3 by inelastic neutron scattering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2003;15:3741–3749. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/15/22/308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thalmeier P. Bound state of phonons and a crystal field excitation in CeAl2. J. Appl. Phys. 1984;55:1916–1920. doi: 10.1063/1.333518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundermann M, et al. The quartet ground state in CeB6: an inelastic x-ray scattering study. Europhys. Lett. 2017;117:17003. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/117/17003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Supplemental Information available online at 10.1038/s41467-022-33468-6.

- 32.Murani AP, Reske J, Ivanov AS, Palleau P. Evolution of the spin-orbit excitation across the gamma-alpha transition in Ce. Phys. Rev. B. 2002;65:094416. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.094416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dvorak J, Jarrige I, Bisogni V, Coburn S, Leonhardt W. Towards 10 meV resolution: the design of an ultrahigh resolution soft X-ray RIXS spectrometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016;87:115109. doi: 10.1063/1.4964847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brookes N, et al. The beamline ID32 at the ESRF for soft x-ray high energy resolution resonant inelastic x-ray scattering and polarisation dependent x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res. B. 2018;903:175–192. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2018.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kummer K, et al. RixsToolBox: software for the analysis of soft X-ray RIXS data acquired with 2D detectors. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2017;24:531–536. doi: 10.1107/S1600577517000832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braicovich L, et al. The simultaneous measurement of energy and linear polarization of the scattered radiation in resonant inelastic soft x-ray scattering. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014;85:115104. doi: 10.1063/1.4900959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bickers NE. Review of techniques in the large-N expansion for dilute magnetic alloys. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1987;59:845. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.59.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawrence JM, et al. Slow crossover in YbXCu4 (X = Ag, Cd, In, Mg, Tl, Zn) intermediate-valence compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 2001;63:054427. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.63.054427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blaha, P. et al. An Augmented Plane Wave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties (Karlheinz Schwarz, Techn. Universität Wien, Austria, 2018).

- 40.Blaha P, et al. WIEN2k: an APW+lo program for calculating the properties of solids. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:074101. doi: 10.1063/1.5143061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werner P, Comanac A, de’ Medici L, Troyer M, Millis AJ. Continuous-time solver for quantum impurity models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:076405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.076405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boehnke L, Hafermann H, Ferrero M, Lechermann F, Parcollet O. Orthogonal polynomial representation of imaginary-time Green’s functions. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:075145. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.075145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hafermann H, Patton KR, Werner P. Improved estimators for the self-energy and vertex function in hybridization-expansion continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:205106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.205106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hariki A, Yamanaka A, Uozumi T. Theory of spin-state selective nonlocal screening in Co 2p x-ray photoemission spectrum of LaCoO3. J. Phys. Soc. Japan. 2015;84:073706. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.84.073706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malterre D, Grioni M, Weibel P, Dardel B, Baer Y. Evidence of a Kondo scale from the temperature dependence of inverse photoemission spectroscopy of CePd3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992;68:2656–2659. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souma S, Kumigashira H, Ito T, Takahashi T, Kasaya M. Ultrahigh-resolution photoemission study of CePd3: absence of Kondo insulator gap. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2001;114-116:735 – 740. doi: 10.1016/S0368-2048(00)00386-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hariki A, Winder M, Uozumi T, Kuneš J. LDA + DMFT approach to resonant inelastic x-ray scattering in correlated materials. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;101:115130. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.115130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the OpARA database of TU Dresden under accession code 123456789/5706.

All numerical codes in this paper are available upon reasonable request to the authors.