Abstract

Introduction

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) provides a path for individuals who are undocumented to join the physician workforce. Indeed, recipients of DACA can play an important role in addressing health inequities in medicine. Although DACA has been in place since 2012, many medical schools remain unaware of it or are hesitant to consider recipients for admission. In a similar vein, the premedical community, including those with DACA status, may be unaware of their eligibility and the steps necessary to pursue medicine. Further education and outreach are needed to achieve institutional policies conducive to the inclusion and success of those undocumented in medicine.

Methods

We created an hour-long workshop to empower learners with key knowledge relevant to DACA policy and its impact on medicine. We evaluated the workshop through pre- and postworkshop questionnaires assessing participant knowledge and attitudes based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB).

Results

A total of 112 participants engaged in our workshop. Ninety-one pretests and 61 posttests were completed by attendees. Data revealed a significant increase in performance on all knowledge-based and TPB questions, including intention to participate in future policy development. Moreover, participants reported appreciating the interactive nature of the session and expressed feelings of empowerment by their newfound knowledge base.

Discussion

This workshop provides a promising foundation from which conversations and progress regarding DACA-related medical education policy can begin. Specifically, the workshop engages participants in the process of identifying actionable steps for overcoming barriers to inclusion and support.

Keywords: Case-Based Learning, Cultural Competence, Diversity & Inclusion, Health Care Workforce, Health Equity, Health Policy/Health Care Reform, Recruitment, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

Educational Objectives

By the end of this workshop, participants will be able to:

-

1.

Describe the history, status, and effects of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) legislation on students pursuing medical education.

-

2.

Discuss the impacts of DACA and its recipients on medical education and health care.

-

3.

State examples of challenges faced by DACA recipients when applying and matriculating into medical school.

-

4.

List specific barriers that DACA recipients face in becoming practicing physicians.

-

5.

Identify actionable steps that schools considering admission of DACA recipients can take to achieve policy that fosters success and equity for DACA recipients.

Introduction

In June of 2012, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was introduced as a policy to protect those brought to the United States as minors.1 Under DACA, individuals who entered the US at age 16 or younger receive protection from deportation and work authorization. In 2019, when the Supreme Court heard a case involving the Trump administration's rescinding of DACA, the Association of American Medical Colleges released an amicus brief advocating for DACA as continued legislation.2 This statement explicitly supported recipients as an important part of the health care and physician workforce.

It is estimated that a recipient of DACA who becomes a physician will care for approximately 10,000 patients throughout their career.3 Moreover, most with DACA status are bilingual and come from medically underserved communities.3 Additional literature has reported that individuals from underserved communities are more likely than those not from underserved communities to work in areas of similar need.4 Therefore, physician recipients of DACA are likely to fill critical gaps in medical care. Nonetheless, there remain multiple barriers to matriculation as well as shortcomings in support systems necessary to allow these individuals to thrive in medical education.1 Examples of such barriers include the limited number of medical schools that accept DACA status, ineligibility for federal loans, and limited institutional support.

As of 2021, 65 of the 154 US allopathic medical schools consider recipients of DACA for admission. The limited number of medical schools that do so includes schools that give preference to in-state applicants, further narrowing options nationwide. Moreover, a disproportionate number of schools that offer considerable financial support are highly competitive private institutions with low acceptance rates.5 Those with DACA status are ineligible for federal assistance programs or federal loans.6,7 These restrictions add financial stress during undergraduate studies, and many students must work to cover costs while attending school.7 Medical education tuition is particularly expensive and may present financial strain for many regardless of immigration status. Without the ability to apply for federal loans, those with DACA status must explore alternatives that are limited, inconsistent, and more expensive to acquire (e.g., private loans).6 There are presently a limited number of DACA-friendly institutions offering assistance in navigating these options.4

Although these numbers are promising, more must be done to enhance medical educators’ and administrators’ understanding of DACA.8 Prior efforts to improve diversity and inclusion at the medical education admissions level have been shown to improve confidence in addressing DACA generally.9 However, similar sessions aimed at diversity in academia have prompted specific calls for discussion that more explicitly centers this policy.10 Indeed, to integrate and support those with DACA status in medicine, it is pivotal to implement more intentional efforts to ensure adequate understanding and support from medical institutions looking to welcome these students.

This workshop provides an educational resource that can inform, motivate, and empower participants to include DACA recipients in medical education. Through learning and increased awareness, participants can begin to pursue and more effectively build policy that maximizes the success of DACA recipients throughout medical education and beyond. This session is specifically designed to engage individuals who contribute to institutional decision-making (e.g., administration, faculty, admissions staff) and those who contribute to the overall environment of medical education communities (e.g., students).

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) provided a theoretical framework for the development of the workshop.11 TPB states that a person's behavior is largely related to and predicted by their intentions. TPB posits that three major components contribute to a person's intention to act: attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms. The goal of the workshop was to address these three tenets (e.g., improving a participant's personal attitudes towards DACA in medicine), thereby theoretically impacting participants’ intentions to engage in the development of DACA-related policy at their institutions. Consistent with Kern's six-step model of curriculum development, our team conducted a literature review after identifying the overall problem.12 That review revealed no prior MedEdPORTAL publications specifically dedicated to this topic. Again, following Kern, the team subsequently outlined learning objectives and created a PowerPoint presentation with case studies.12

Methods

Background

In developing this 60-minute workshop, we used a literature review and firsthand conversations with administrators at various medical institutions to gather information and build a workshop that would both inform and act as a starting point for policy development. Much of the workshop was developed after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in-person and virtual versions of the workshop were created.

Workshop Presentation

We held the workshop six times—once in person and five times virtually. Participants attended from 17 different academic institutions. Each workshop was led by a minimum of two facilitators. Participant learners were recruited by email and word-of-mouth invitations. For example, as facilitators, we announced workshops through student-led organizations within our schools (e.g., the Latino Medical Student Association).

Participant and Facilitator Preparation

The workshop addressed DACA policy logistics, the impact of those with DACA status in medicine, challenges in pursuing medical education and practicing medicine with DACA status, and potential solutions to these challenges. No previous knowledge of DACA was necessary to engage in the workshop. However, facilitators needed to have familiarized themselves with any policy in place at their respective institutions as well as with the general content discussed in the curriculum to adapt the presentation as needed. The workshop consisted of an interactive PowerPoint-based presentation that included opportunities for audience response, small-group discussions, and collaborative brainstorming.

Summary of Workshop Flow

Prior to the start of the workshop, participants completed a preworkshop evaluation (Appendix A). We began the session with a PowerPoint (Appendix B) teaching the particulars of DACA, including its history and current state. Using the facilitator guide (Appendix C), we then defined DACA, detailed relevant court rulings, presented recipient demographics, and explained examples of various barriers faced by students with DACA status in their paths to medical school. After the initial presentation, we divided into groups preferably no larger than 10 people including the facilitator. Each facilitator guided a case discussion concerning an experience relevant to either medical students with DACA, premedical students, or medical school administrators. There were four possible cases (Appendices D–G) to choose from depending on group size. Attendees were encouraged to integrate information from personal experience and the presentation to answer corresponding questions. Participants then reconvened as a large group, and a spokesperson from each small group shared their takeaways.

In the second part of the workshop, we discussed solutions that have been implemented to combat the issues discussed earlier. This was followed by a large-group brainstorming opportunity in which participants discussed feasible paths forward to develop/improve DACA-related policy at their schools. The workshop closed with a general question-and-answer session as well as an invitation to complete a postworkshop survey (Appendix H).

Pre- and Postworkshop Surveys

All study and evaluation protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albany Medical College (IRB 4999, July 2018, deemed exempt). Prior to engaging in the workshop, participants completed a 13-item preworkshop survey consisting of demographic items, 7-point Likert ratings of attitudes surrounding DACA/perceived knowledge of DACA, and multiple-choice questions assessing actual knowledge of DACA (Appendix A). Immediately following the workshop, participants completed a 10-item postworkshop survey with the same 7-point Likert items and multiple-choice questions as well as additional general feedback questions (Appendix H). We developed all items based on our learning objectives and TPB framework.11 No formal validity assessment was done. However, we reviewed all survey responses after completion of each individual session. The workshop was then iteratively edited to incorporate feedback. We determined the efficacy of the module by comparing relative (i.e., pre- vs. posttest) scores on perceived knowledge as well as actual knowledge about DACA in medicine and relative responses (i.e., pre- vs. posttest) on a series of items based on TPB.11

Statistical Analysis

We used a standard Levene's test for equality of variances to conduct between-groups comparisons (i.e., post- vs. pretest) for 12 of 13 measures. One question did not violate the assumption of homogeneity, and a normal t test was used. Because we did not find homogeneity of variance, we used a nonparametric t test.

We performed Welch's t tests to determine if there was a statistically significant increase in mean correct responses, attitudes, and reported understanding from before to after the workshop for the 12 measures violating the assumption of homogeneity. We performed a standard Student t test to determine if there was an increase in positive attitude towards subjective norms as this measure met the assumption of homogeneity of variance. We conducted all statistical analyses on STATA 17.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Pre- and Postworkshop Survey Completion

One hundred twelve preworkshop surveys were filled in. Of these, 16 were incomplete, and five had missing responses, leaving a total of 91 complete preworkshop surveys.

Seventy-one postworkshop surveys were filled in. Of these, eight were incomplete, and two had missing responses, for a total of 61 complete postworkshop surveys.

Participant Demographics

The final sample consisted of 91 participants, with 61 (67%) completing the postworkshop survey. Sixty medical students composed 66% of the sample. The majority of participants identified as either Latinx/Hispanic (24%) or White (26%). Participants reported affiliations with institutions in eight different states, including New York (36%), California (25%), and Pennsylvania (16%). Most respondents (56%) were unsure whether their institution considered applicants who were DACA recipients for admission. Demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Workshop Participants (N = 91).

Reported Understanding of DACA

Participants reported a significant overall increase in their perceived understanding of DACA in medicine after participating in the workshop relative to before attending. The biggest increase was seen in self-reported ability to list barriers recipients of DACA face in practicing medicine (mean difference = 2.5, p < .001). Specifically, participants went from generally neither agreeing nor disagreeing they were capable of this to moderately agreeing they could. Similar changes were seen across all four reported understanding items, which notably assessed Educational Objectives 1–4. The comprehensive findings are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Participants’ Reported Understanding of DACA in Medicine Before and After Participation in the Workshop (Pretest N = 91, Posttest N = 61).

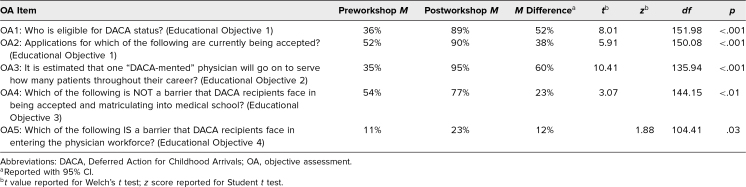

Actual Knowledge of DACA

There was a significant increase in total study sample accuracy on all items objectively assessing knowledge of DACA after participating in the workshop compared to prior. Full comparisons of mean correct response rate on items assessing actual knowledge of DACA can be found in Table 3. The largest increase was on the item assessing understanding of the impact recipients of DACA can have in health care (mean difference = 60%, p < .001), whereas the least substantial shift occurred on the item requiring participants to identify barriers to practicing medicine as a recipient of DACA (mean difference = 12%, p = .03).

Table 3. Participants’ Performance on Multiple-Choice Items Assessing Knowledge of DACA in Medicine Before and After Participation in the Workshop (Pretest N = 91, Posttest N = 61).

Theory of Planned Behavior

Participants collectively exhibited significant gains on all TPB items after the workshop. Notably, the largest shift was in perceived behavioral control. Prior to the workshop, participants generally reported somewhat disagreeing that they could identify strategies towards building DACA-related policy at their institutions, whereas afterward, they moderately agreed that they were capable of doing this (mean difference = 2.8, p < .001). The smallest increase was in subjective norms. Specifically, participants initially believed that attitudes towards DACA amongst people in medicine were neither positive nor negative but reported them to be somewhat positive after the workshop (mean difference = 0.7, p < .01). Pre- and postworkshop responses to TPB items are found in Table 4.

Table 4. Participants’ Response to TPB Items Before and After Participation in the Workshop (Pretest N = 91, Posttest N = 61).

General Feedback

Participants throughout expressed extensive satisfaction with the amount of information covered as well as with the interactive nature of the workshop. They similarly praised the integration of anecdotes and experiences, whether personal or reported. Early iterations received comments about transitions between small- and large-group components taking excessive time. Additionally, early attendees requested that future presentations integrate more information on the demographics of DACA recipients (e.g., country of origin, US location) both overall and within the field of medicine. Importantly, later attendees expressed satisfaction with the inclusion of a “Who is DACA?” slide and moreover commented enjoying the large-group format of final brainstorming.

Discussion

The purpose of this workshop was to create a setting in which members of the medical education community nationwide could gain the knowledge and empowerment necessary to include DACA recipients in medical education. Postworkshop results indicate more favorable attitudes toward DACA recipients and more favorable opinions about whether inclusion at respective institutions is possible. Overall, findings affirmed the workshop to be relatively effective, informative, and motivational, thus achieving the goal of increasing knowledge and awareness that can lead to policy change. Importantly, participants provided consistent feedback noting extensive knowledge gained during the session as well as powerful takeaways from collaborating with their peers during breakout sessions. Also reported was an appreciation of the workshop flow culminating in opportunities to develop actionable ideas. Indeed, many participants expressed an overall desire to move toward change at their respective schools. The analysis of pre- and postworkshop items did not assess whether participants enacted changes, created new policies, or otherwise made changes at their respective institutions. This is a limitation of the scope of the workshop and its learning objectives.

Anecdotal comments about intention for action are supported by the results of the TPB items on the surveys. For example, compared to before our workshop, participants exhibited significantly more positive attitudes towards the impact of DACA in medicine after completing the session. Participants also perceived more positive attitudes amongst their peers, potentially due to collaboration during the workshop. Lastly, the workshop resulted in increased self-reported abilities to develop DACA-related policy and increased intention to develop actual policy after engaging in active brainstorming. Again, assessment of whether participants enacted change was not studied long term.

The workshop was presented successfully both in person and virtually. Due to COVID-19, all sessions but one were virtual. The facilitator guide (Appendix C) included instructions on variations of the presentation in both settings. Breakout group functions in online platforms allowed easy transitions into case study sessions. Similarly, the use of question-and-answer features (e.g., Poll Everywhere in person, Zoom Questions online) allowed for interaction throughout the presentation.

There were several challenges in the development of this workshop. For example, it was difficult maintaining audience participation while communicating the relevant information in a timely manner. We therefore shortened the extent of other background information to place more time and priority on discussion. Virtual sessions often ran long, and so, timing was further refined. Additionally, the format of the questions (embedded in the presentation vs. using applications) had to be adjusted based on mode of presentation (virtual vs. in person, respectively). Based on participant feedback, it was also necessary to add information on demographic data to improve context. Finally, throughout the development process, the ongoing pandemic created obstacles with recruiting participants and organizing virtual events while maintaining intended objectives. The efficacy of a virtual format for this presentation nonetheless demonstrates that virtual options, such as those necessitated by COVID-19, can increase accessibility.

After the above challenges were overcome, several limitations remained. Despite postworkshop questionnaires being offered directly after the session's conclusion, some participants did not complete them. The workshops’ online delivery further impacted the response rate as participants often exited prematurely. The audience members’ knowledge of DACA and their institutions’ policies was an additional potential limitation. Many of the workshops were presented to audiences with prior knowledge of DACA, such as those from institutions with existing DACA-related admissions policies. This may have confounded reported intention to engage with future policy development. Indeed, only one host institution had no prior DACA policy in place. More data should be acquired from institutions that currently have no policy in place to properly assess whether perceived prior knowledge of DACA influences the effectiveness of the workshop.

Pre- and posttests exhibited several limitations as well. For example, question items were not able to fully capture the breadth of information presented during the workshop. Similarly, multiple-choice evaluation of the impact of DACA in medicine likely did not accurately reflect participants’ changes in awareness. However, identifying shifts in participants’ attitudes towards DACA in medicine, as well their perception of the attitudes of others (i.e., subjective norms), may have provided a more comprehensive measure of this understanding via TPB.11 Notably, we also evaluated participants’ abilities to list challenges faced by recipients of DACA when pursuing education and ultimately practicing medicine via multiple-choice questions. It may be more effective to have participants list barriers in a free-response format. Questionnaires moreover did not require participants to explicitly identify steps towards improving DACA policy. However, through the lens of TPB, by yielding a general increase in participants’ self-reported ability to identify these steps (i.e., their perceived behavioral control), we may have captured a proxy for a genuine ability to do so.11

Lastly, the project was limited in scope as the workshop measured intent to engage, rather than actual engagement, in policy development. Furthermore, the workshop did not address broader issues impacting undocumented students as whole, including those without DACA protections. The workshop therefore did not cover many issues and questions likely to arise in discussing immigration. Thus, presenters may need to be prepared for some follow-up, particularly at institutions with no policies in place.

The ideal long-term outcome of the workshop is increased implementation of policies that allow DACA recipients to apply to, and ultimately thrive at, medical schools across the country. It follows that this workshop would best serve presenters in the setting of educational development for institutional decision-makers and faculty (e.g., as part of inclusion training). Additionally, the workshop may be effective for those seeking to foster a more culturally competent educational environment (e.g., amongst medical students). Emphasis should be placed on participant engagement and the broader context of DACA policy, including its impact and current status. Future work could investigate tangibly measuring the effectiveness of the workshop and similar tools by assessing long-term change. For example, follow-up with institutions at which the workshop was/is presented might allow for qualitative observation of the development of policy advancement, or lack of same. The framework of the workshop and evaluation of its efficacy (i.e., via TPB) may offer an example that other medical education policy initiatives can follow. Our findings provide a promising foundation on which to incorporate working toward integration and inclusion of DACA recipients for the betterment of medicine.

Appendices

- Preworkshop Survey.docx

- DACA Workshop Slides.pptx

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Case 1.docx

- Case 2.docx

- Case 3.docx

- Case 4.docx

- Postworkshop Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Latino Medical Student Association (LMSA) Northeast regional organization, as well as LMSA chapters at Albany Medical College and Upstate Medical University, for their assistance in promoting our workshop to participants. We similarly would like to thank Jennifer Welch, Ann Botash, Krystal Ripa, Kelly Donovan, and Nakeia Chambers for helping bring the presentation to a wider audience of medical education administrators. We also thank Dr. Branden Eggan for her advice on building a productive and progressive curriculum. Lastly, we would like to thank Gloria Munayco for her help in presenting early iterations of the workshop.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Prior Presentations

Garcia A, Lapidus A, Lorenzana De Witt M, et al. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA): maximizing impacts in medical education & healthcare. Poster presented virtually at: AAMC Group on Student Affairs & Organization of Student Representatives Spring Meeting; April 14–17, 2021.

Ethical Approval

The Albany Medical College Institutional Review Board approved this project.

References

- 1.Nakae S, Rojas Marquez D, Di Bartolo IM, Rodriguez R. Considerations for residency programs regarding accepting undocumented students who are DACA recipients. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1549–1554. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brief for Amici Curiae Association of American Medical Colleges et al., in Support of Respondents, Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, 140 S Ct 1891 (2020) (Nos. 18-587, 18-858, 18-859).

- 3.Ramos JC, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Gillezeau C, et al. The impact of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) medical students—a scarce resource to US health care. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):429–431. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuczewski MG, Brubaker L. Medical education as mission: why one medical school chose to accept DREAMers. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;43(6):21–24. 10.1002/hast.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh R. Applying to medical school as a DACA recipient. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1064. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arias FD. The barriers to medical school for DACA students continue. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1072. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regan E, McDaniel A. Examining DACA students’ financial experiences in college. Educ Res. 2019;48(8):564–567. 10.3102/0013189X19875452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talamantes E, Bribiesca Y, Rangel-Alvarez B, et al. The termination of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) protections and medical education in the U.S. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;22(2):353–358. 10.1007/s10903-019-00891-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakae S, Kothari P, Johnson K, Figueroa E, Sánchez JP. Office of Admissions: engagement and leadership opportunities for trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:11018. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto-Greene M, Culbreath K, Guzman DE, Sánchez JP, Romero-Leggott V. Diversity and inclusion in the academic medicine workforce: encouraging medical students and residents to consider academic careers. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10689. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT, eds. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. 2nd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Preworkshop Survey.docx

- DACA Workshop Slides.pptx

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Case 1.docx

- Case 2.docx

- Case 3.docx

- Case 4.docx

- Postworkshop Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.