Abstract

In Ethiopia, urban areas are defined basically as places having a minimum population of 2,000. The current coverage of urban areas in the country is less than 20%, and even the majorities are small towns that account more than 85% of the urbanized areas in the country. However, urbanization in the country is increasing rapidly, at a rate of 4.63% annually. Spatially, the highest urbanization ratios occur in small towns surrounding the Ethiopia's capital city, Addis Ababa. Still, the recently urbanized areas are characterized as shanty, slum and spontaneous. On the other hand, the current rate of urbanization in the country indicates that there will be more urbanized areas in the future, which need better urban planning and management. Therefore, the purpose of this research was to identify the key drivers of the development of Ethiopia's urbanization, and to identify the management gaps that could help to predict future urbanization hotspots and trends from their early stages. Methodologically, both primary and secondary data sources were systematically applied: current urban planning and related documents, as well as land-use plans, and furthermore, high resolution historical satellite imageries of 2005, 2008 and 2018 from Google Earth Pro were analyzed. Complementary, and for validation purposes interviews and focus group discussions with experts were carried out between 2018–2021, together with on-site investigation. The results show that the drivers for the emergence of spontaneous urban development in Ethiopia relate primarily to socio-cultural components, such as in the case of worshiping places, local markets, educational and administrative centers. Physical infrastructure, such as roads played also a significant but subordinate role in the intensification of such developments. Our results demonstrate how an ineffective management of these factors has contributed to a dysfunctional urban growth. Finally, a green field level proactive planning approach is proposed and commented.

Keywords: Haphazard urbanization, Land-cover changes, Planning approach, Sebeta, Spatial drivers, Spontaneous development

Haphazard urbanization; Land-cover changes; Planning approach; Sebeta; Spatial drivers; Spontaneous development.

1. Introduction

Globally, human settlements tend to increase in population size and physical development gradually (Antrop, 2004; Babalola, 2012; Wu, 2014), from scattered rural settlements to more concentrated and agglomerated built-up spaces of urban areas, roughly in the order of the following succession:

Hamlet → Village → Town → City → Conurbation (A. Girma, 2013; OECD, 2016; Young, 1999). This transformation process and the consequences from rural to urban denotes urbanization (Cohen, 2006; Farrell, 2017)and it has long been associated with human development and progress (Kuddus et al., 2020).

The World Bank report (2021) on urban development indicates that about 80% of global GDP is generated in cities, and if managed well, urbanization can contribute to sustainable growth by increasing productivity, allowing innovation and new ideas to emerge (UN-Habitat, 2022; World Bank Group, 2022). Besides its multidimensional advantages, urbanization is also associated with negative environmental impacts and exacerbates socio-cultural problems. It largely contributes to the decline of ecosystem services, among them air and soil pollution and loss of biodiversity (Zhao et al., 2006; Li et al., 2016; Du and Huang, 2017), as well as loss in arable and forest areas, and degradation of wetlands and water bodies (Fazal, 2000; Hu et al., 2007; Islam et al., 2014).

Urbanization also creates energy dependent society due to high standard of living and it is an indicator of energy-inefficient society (Streimikiene et al., 2021), it usually expose peri-urban farmers to loss agricultural land as urban expansion changes land available for agriculture (Ayele and Tarekegn, 2020). The best example of urbanization trends that contribute to unmanaged land use change specially to farm land is spontaneous development, which is a type of urban growth that leads to an increase in the number of urban patches and acts as a diffusion mechanism (Benti et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2011).

At all scales, the sustainable urbanization necessitates of planned urban development, established competent institutional frameworks, and proactive management and governance strategies (Dube, 2013). However, the severity of impacts of urbanization are manageable in small urban areas compared to large cities as the scale of impacts tend to be limited (Abou-korin, 2014) and basically small towns are an inherent component of urbanization, and in the future, most of globalization is expected to occur in them (Alaci, 2010; Tola et al., 2021). In addition, small cities/towns have a limited physical and demographic footprints and contribute relatively less to the national economic agglomeration, but they have important ecological impacts (Terfa et al., 2020). As a result, understanding urban growth and the associated effects at their early stage of development is crucial to propose appropriate measures help for sustainable urban planning (Haregeweyn et al., 2012).

The urbanization process has increased rapidly in the last few decades, and large numbers of small urban centers have emerged, particularly in the global south (Cohen, 2006). In Ethiopia, urban areas are basically defined as places having a minimum population of 2,000 (Ministry of Urban Development and Construction (MUDCo), 2012; National Labour Force Survey (NLFS), 2005; Schmidt and Kedir, 2009) and areas having a population from 2,000 to 20,000 are classified as small towns that account more than 85 percent of the urbanized areas in the country (MUDCo, 2012). The small urban areas are the bridge between the rural-urban and urban-urban linkages by serving as the production and distribution centers for goods and services (MUDCo, 2012). At the small town scale a minimum of ‘basic plan’ (i.e. the initial urban plan in Ethiopia) is required to manage the effective growth of small urban areas (MUDCo, 2010). However, most urban developments in the country are characterized by spontaneity and rapidity (Matt Burdett, 2018) usually emerging from informal settlements (Terfa et al., 2017).

In Africa, urbanization is leading to significant land use changes since the continent is undergoing rapid urbanization and population growth in recent decades (Arsiso et al., 2018). In particular, small towns in sub-Saharan African countries', including Ethiopia, usually face challenges by the absence of land-use planning, eg, designated space for food production and unfavorable land-use changes (Tola et al., 2021). Most research on urban expansion in Ethiopia was primarily focused on the analysis of urban growth and urban land use changes in the capital city and other regional capitals, but studies on the spatial growth of small cities/towns and their influences were quite limited (Terfa et al., 2020).

The Oromia Special Zone surrounding Finfinnee/or Addis Ababa/experienced an accelerated growth in the built-up areas and scattered spatial growth in Ethiopia (Terfa et al., 2020). For example, in the towns of Sebeta, Burayu, Gelan and Dukem, Legatafo, and Sululta, informal settlements have expand at an alarming rate, occupying more than 30% of the existing settlements (Lirebo, 2006; ORAAMP, 2002). In the case of Sebeta, our case study, more than 51 percent of the residential area is covered by informal settlements (Chaka, 2018), and also exhibits informal patterns of land use: unplanned and dispersed developments and sprawling growth over farmlands and natural landscapes (Solomon B. and Hailu W., 2015).

In general, spontaneously emerging settlements in Ethiopia contributed to the random urban growth, and undesirable changes to the natural, agricultural and related landscapes (Benti et al., 2021). In order to manage the growth of spontaneous settlements from their early stages and reduce their impacts on natural and working landscapes, the driving factors, particularly the spatial drivers behind their formation, were largely overlooked and mostly spoken by urban historians. However, the factors that drive the formation of urban areas are a major issue in urban development, making proactive management approaches necessary (Kantakumar et al., 2020). In addition, the previous studies show that identifying the driving factors for urban development help to predict future urbanization hotspots and direction of urban expansion (Benti et al., 2021; X. Li et al., 2021).

Ethiopia has experienced rapid urbanization over the past three decades. Several cities expanded rapidly and many satellite towns sprung up around the major cities (Koroso et al., 2021). The study by Jenberu and Admasu (2020) revealed that one of the driving factor for the rapid urbanization in the country is migration. However, in Ethiopia, the driving factors behind the formation and spontaneous development of the Ethiopia's existing urban areas were overlooked, and their associated consequences are less understood and identified. Overlooking the drivers of spontaneous urban development from their inception hampered the country's ability to implement appropriate urbanization management approaches that can guide the sustainability of future urban centers from their early stages. As a result, urban expansion and growth are influenced by spontaneously emerging settlements, which, in the long run, result in the formation of slum-like urban areas.

Therefore, the primary objective of this research is to identify key drivers for the inception of spontaneous settlements in Ethiopia, with a focus on spatial determinants, and to contribute proactive planning and policy recommendations that can improve sustainable urban development that help for large audiences interested in the topic and to the science at local, regional and global scales.

2. Materials and methodology

2.1. Location and description of the study area

The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey of the CSA-Ethiopia (2017) shows that around 80% of the 95 million inhabitants of the country live in rural areas (CSA-Ethiopia, 2017). Most of these rural communities share health care, schools, markets, electricity and similar services from their nearby small towns, but such towns usually face challenges related to capacity, management, and immigrations to provide the services effectively (CSA- Ethiopia, 2017; MUDCo, 2012).

The selection of the study area aimed to identify small towns that confront the challenges of arbitrary growth of settlements and aims to represent the drivers and the magnitude of spontaneous urban development in the fast emerging small towns in Ethiopia. In this regard, Addis Ababa, with its rapid urbanization, is under constant pressure from the surrounding towns (Meskerem et al., 2017), and inversely, the city also challenges the development of nearby towns in the Oromia Special Zone Surrounding Addis Ababa (OSZSA), through urban sprawl and boundary overlapping (Girma et al., 2019; OWWDSE, 2011).

The special zone (Figure 1a and b) covers an area of 4,300 km2 and consists of six districts and eight (7) large towns with 7,000 to 50,000 inhabitants (Mohamed and Worku, 2019; OWWDSE, 2011). These towns are Sebeta, Burayu, Holeta, Sululta, Lega Tafo, Sandafa & Bake, Gelan & Dukem, and the boundaries of three (3) towns, Sebeta, Burayu, and Gelan & Dukem, overlap with the Addis Ababa city (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area: the OSZSA in relation to Ethiopia and the Oromia regional state (a); the OSZSA, towns in the OSZSA and the capital city of the country (b); towns of the OSZSA that overlaps with the capital (c).

Sebeta town is located at latitude 8◦52′30″–8◦59′30″ North and longitude 38◦34′00″–38◦42′30″ East (Terfa et al., 2020), and about 25 km away the southwestern fringe of Addis Ababa city (Girma et al., 2019). It was selected as a study area because of its large boundary overlap with the capital city, and containing large natural environments affected by spontaneous urbanization (Benti et al., 2021; Y. Girma et al., 2019; Gutema, 1997).

Due to its proximity to Addis Ababa, the Sebeta town is also become the home for many people who work in the capital (Andualem, 2019) and the factors that triggered the development of the capital also contributed to the emergence of the Sebeta town (Benti et al., 2021; Chaka, 2018; Girma et al., 2019; OWWDSE, 2011).

Sebeta is also one among the top industrial hub in Ethiopia. There are 418 manufacturing companies in the town, from breweries, steel, liquor, cement factories, and water bottling companies. In addition, there are hundreds of agro-industrial initiatives, including flower farms and other companies in various sectors, and around 20 real estate developers (Chaka, 2018; OWWDSE, 2011; Taye M., 2013).

Sebeta has experienced high rural immigration and the expected population growth is high (Chaka, 2018; Y. Girma et al., 2019), which contributed to different population figures indicated various data sources. The Sebeta town had a population of 14,100 in 1994 and 49,331 in 2007 (CSA-Ethiopia, 2007), and was estimated in more than 167,000 for 2017 (CSA, 2013; Terfa et al., 2020). On the other hand, the municipality of Sebeta has documented that the town population is around 336,975 inhabitants, with a growth rate of 4.5% in 2020. This has made it even more attractive for investors, as they can easily access employees from the town (Andualem, 2019).

Furthemore, the town is also in an area known for its natural resources endowment, surrounded by mountains, hills, seasonal marshy plains, rivers and streams, some of them of importance for the Oromo culture and religion -‘Waaqefataa’ (OUPI, 2018; Sebeta City, 2019; Gutema, 1997). For instance, the spring of the Wachacha Mountain served as a water supply for Addis Ababa city, which continued until the Italian occupation, and still some water is being bottled and shipped from there (Mahiteme, 2007).

Therefore, the selected study area is not only represent the nature of small towns, but also represent the largest expansion zone of the Ethiopian capital that have significant impacts on its nearby towns sharing borders. Consequently, it can be a good learning example for urban areas in the country having equal or lesser impact on each other than the study area. Although the case study area is used to show the contribution of the spatial drivers in the emergence of spontaneous settlements, the finding of the study area can largely contribute to the urban and regional planning related science at local, regional and global scales in indicating the possible pull factors for such settlements mostly for countries under fast emerging towns.

2.2. Data types and sources

The absence of pre-formulated data types and sources that help to identify the spatial driving factors for the emergence of spontaneous urban development in Ethiopia, both the primary and secondary data types and sources indicated in the naration below were used for the qualitative and quantitative data analysis approach. Opinions and views of key experts and officials; Experiences of urban historians, and members of the Sebeta town's elder community, and the experience of the researchers were the main sources of primary data. These types of data sources were recently applied by the other researchers (Alem, 2021; A. Girma, 2013; Y. Girma et al., 2019; Sahle et al., 2019). The secondary data used in this study came from urban planning documents, published and unpublished research and working papers, and free satellite imagery, and such types of data were also used by (Alem, 2021).

The Ethiopian urban planning documents such as standards and manuals of 2012, the 2008 proclamations were collected from the Ministry of Urban Development and Construction (MUDCo). The 2002, 2016 urban plan documents related to the city of Addis Ababa were collected from the Addis Ababa City Master Plan Project Office. Urban planning documents (manual and standard) of the towns of the OSZSA in the regional state of Oromia which was prepared in 2008, were collected and compiled from the Oromia Urban Planning Institute (OUPI) in 2018–2019.

In addition, the drawings and reports of the first structure plan (SP) of the town of Sebeta that served for 2008–2018, and the recent proposal for 2018–2028 were collected from its municipality and the OUPI in 2019–2020. The other secondary data sources were cloud-free historical satellite imagery of the 2005, 2008 and 2018 containing the Sebeta town and its surrounding that were downloaded from Google Earth Pro. The Geographical Information System (GIS) was used to show the spatial drivers, which was similarly applied by (Gebeyehu, 2015; Kindu et al., 2018) behind the emergence and development of the spontaneous settlements of the town of Sebeta.

2.3. Sample selection criteria

The expert workshop was conducted during the structure plan (SP) revision process of the town in 2018–2019 years, and the corresponding author was participating in the plan making process. 12 experts were purposively selected and the experts involved in the interview were those who had specialized and had profiles, including urban and regional planning (4), environmental planning and landscape design (2), urban historian (4) and urban sociology (2). Most of the respondents were affiliated from the Oromia Urban planning Institute (OUPI) and the municipality of Sebeta town.

Focus Group Discussions (FGD) were conducted in 2018–2019 with the elders who had already known to the Sebeta town municipality, and the urban historians who had prepared documents about the town's history in the past SPs that prepared for the 2008–2018 and 2018–2028 planning years. Altogether 10 people, 4 Urban Historian and 6 Elders of the town including ‘Abaa Gadaa’, were participated in the FGD and the Elders were identified through nomination method as used by Krueger and Casey (2009) and only to include those who were involved in the revision and previous plans of the town in telling the history of the town.

The 2018 satellite image was chosen to map recent settlement patterns and land uses/land cover; 2008 is the year when the town's first SP was prepared and also the year when the OSZSA was established. The 2005 image was used to identify the nature of settlement patterns of pre-SP and represents the year when the 2008 SP was initiated. Reasons for using Google Earth Pro images are lack of high-resolution historical images (Fenta et al., 2017) of the study area and high cloud cover on other freely available satellite images on the specified years.

Finally, the concept of spatial determinants used in this paper is any human-made or natural elements exist physically and triggered the formation of settlements in an urbanization process.

2.4. Data collection and analysis method

Expert interviews, FGD with elders and experts, and physical assessments of the study area were the primary data collection methods. First, interactive interview with key experts was carried out until the achievement of theoretical (idea) saturation (Benti et al., 2021). Then, the contents of secondary data, including urban planning, management, and monitoring documents were systematically reviewed (Heymans et al., 2019), analyzed, and finally compared with primary data.

The 2005, 2008, and 2018 historical satellite imagery were extracted and downloaded from Google Earth Pro. Next, the images were georeferenced and rectified with control points (Techniques, 2017; Tehrany and Pradhan, 2013), and then coordinates were redefined and transformed into the projected Ethiopian coordinate system (WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_37N). Finally land use/land cover changes in the town of Sebeta, which were used to show their implications for planning, were analyzed in ArcMap 10.4 of the Geographical Information Systems (GIS).

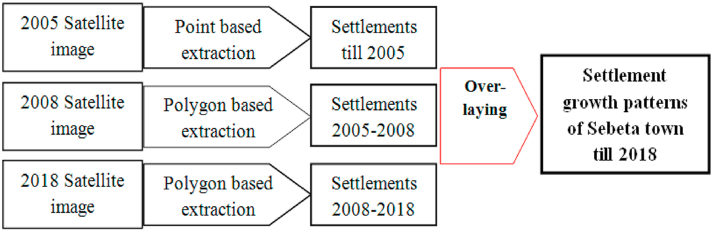

The 2005 image was used as the starting year and point-based settlement digitization (Benti et al., 2021) was carried out in the Arc GIS. Parcel (plot)-based built-up areas in 2008 and 2018 from the non-built-up land cover was differentiated using the supervised classification of the GIS spatial analysis tool (Y. Girma et al., 2019; Mohamed et al., 2019). The spatial changes and the degree of settlement intensification were analyzed by overlaying the settlements of 2005 with the land cover results of the 2008 and 2018 (Figure 2). In addition, several spots of spontaneous settlement intensification processes were shown through the illustration on historical images of Google Earth Pro (Benti et al., 2021; Fenta et al., 2017).

Figure 2.

Satellite images used in the process of identifying settlement growth patterns in Sebeta town.

In general, most of the spatial drivers for the spontaneous settlement intensification in the town were analyzed as follows: First, the historical sections of the town's SP documents were reviewed. Later, urban historians who participated in the Sebeta town SPs were interviewed and the results were compared with the results of the review and verified. Additionally, historians were also asked to locate the spatial drivers on satellite images.

Second, the other driving factors and causes for the intensification of built-up spaces in the town were collected from documented videos, which were recorded throughout the process of the 2018 Structure plan revision of the town. General overviews and discussion points suiting to the research objective were collected from the videos. Further specific details and explanations regarding the factors and causes were obtained through focus group discussion (FGD) with experts. Finally, the spatial drivers were checked and verified through physical observations and mapped using Arc GIS tools (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The process of identifying and verifying the driving factors.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Factors for the development of urban settlements in Ethiopia

According to Davis (2012), communication networks, transport facilities, cultural and ethnic attractions and political pressure are the driving factors for the growth of urban centers.

In the country, however, urban areas have mostly grown spontaneously due to the pre-establishing socio-cultural services and physical infrastructures and pleasant ecological surroundings. Initial settlements usually follow basic social services such as: worshiping areas, education and health centers, and market places and political administrative areas like Palace (Benti et al., 2021; Fasil Giorghis, 2013; Oromia Urban Planning Institute (OUPI), 2010). In addition, settlements usually emerge in areas surrounded by favorable ecological conditions, e.g., abundant water bodies, forests, good climatic conditions and friendly landscapes (Cherenet, 2015) and also environmental conditions play a pivotal role in shaping landscape-scale site patterning (Harrower and Andrea, 2014).

In the earlier Ethiopian cities that served as the seat of government, three institutions: the palace, the market place and the church played the roles of centers for political, economic and socio-cultural activities, respectively. Consequently, the urban planning pattern was also directed and influenced by at least one of these institutions (Office for the Revision of Addis Ababa Master Plan (ORAAMP), 2002). For instance, the Addis Ababa city, from its inception as Government seat of Ethiopia, the city grew around three nodes: the current Palace of the Ethiopian government, worshiping area like the St. George Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Arada building both located around office of the mayor of Addis Ababa, which were the respective political, religious and commercial centers (ORAAMP, 2002). Hence, a congruent pattern of large and scattered settlements started to sprawl around these nodes.

In the case of the Sebeta town, these conditions were met. Before its formal plan, the main socio-cultural facilities and physical infrastructure were already in place, i.e., a local weekly market, schools, and places for worship. Nevertheless, there were precedents of previous activities, like a truck workshop (Figure 4) built in Alemgena (now the 02 Kebele of the town) during the Italian occupation (1935–1941) and after 1956, the basis for the Imperial Haile Selassie Road Training Center (Ethiopian Road Authority (ERA), 2001; OUPI, 2008, 2018), where some residential houses were built as well as shops in the area. The Ethiopian Agricultural Research Institute (EARI) also opened a research station in Sebeta in 1967, which operates as the national center for research into improving fishing yields (Figure 4) and contributes to the town's emergence (EARI, 2009).

Figure 4.

Location of road training and old fishery centers enhanced the establishment of settlements around their vicinity.

3.2. Main spontaneous urbanization drivers

3.2.1. Unclear criteria in defining urban areas and related challenges

In Ethiopia, urban is defined primary as an area having 2000 and above population (MUDCo, 2010, 2012). A summarized experts’ opinion show that “the spontaneous urban developments in Ethiopia are related to the inability of the commencement of urban entitlement and preparing basic plans for areas attained the lowest population required (2000 inhabitants)”. A research conducted by Benti et al. (2021) strengthen this idea and they stated that the major reason for the inability of preparing urban plans as early as possible is lack of sufficient and appropriately trained manpower in the field of urban planning.

Similarly, the definition of urban set in the planning documents of the country is also the other issue for the increment of spontaneous urban developments. The definition request that to get an urban entitlement three-fourth (75%) of the residents of an area should be engaged in non-agricultural activities (MUDCo, 2012). Experts pointed out that “In its most basic aspect, this definition is impractical in the case of Ethiopia, where agricultural activities are the backbone of the economy and about 80% of the population lives in rural areas” [Key Informant Interview (KII), 2020]. In addition, it was mentioned that “It is difficult to define an urban area in terms of non-agricultural economic activities in Ethiopia, as most of the residents of small urban areas in the country operate in multiple locations and multi-purpose economic activities, most of whom are both resident in urban and rural areas” ([Key Informant Interview (KII), 2020)].

Therefore, non-early respond to the minimum population threshold and expecting to gain the specified non-agricultural activities to be an urban area have resulted the emergence and intensification of large spontaneous settlements in the country before the attainment of their basic plans. For instance, the Addis Ababa city has been shaped by history of spontaneous growth. The unplanned mushrooming of micro-dynamic elements in every corner of the city still reinforces the trend of spontaneity against the continuous attempts made to reverse it through planning interventions (MUDCo, 2012; ORAAMP, 2002). As a result, the initial urban plans in the country usually rely on the spontaneously emerging housing conditions, physical infrastructures, and existing patterns in general, which influence the subsequent urban planning. In supporting this idea, Benti, Terefe, & Callo-concha (2021) stated as poor management of spontaneous settlements as early as possible is the greatest planning challenge and usually lead to the formation of slums.

3.2.2. Limited attention given to segregated pioneer settlements

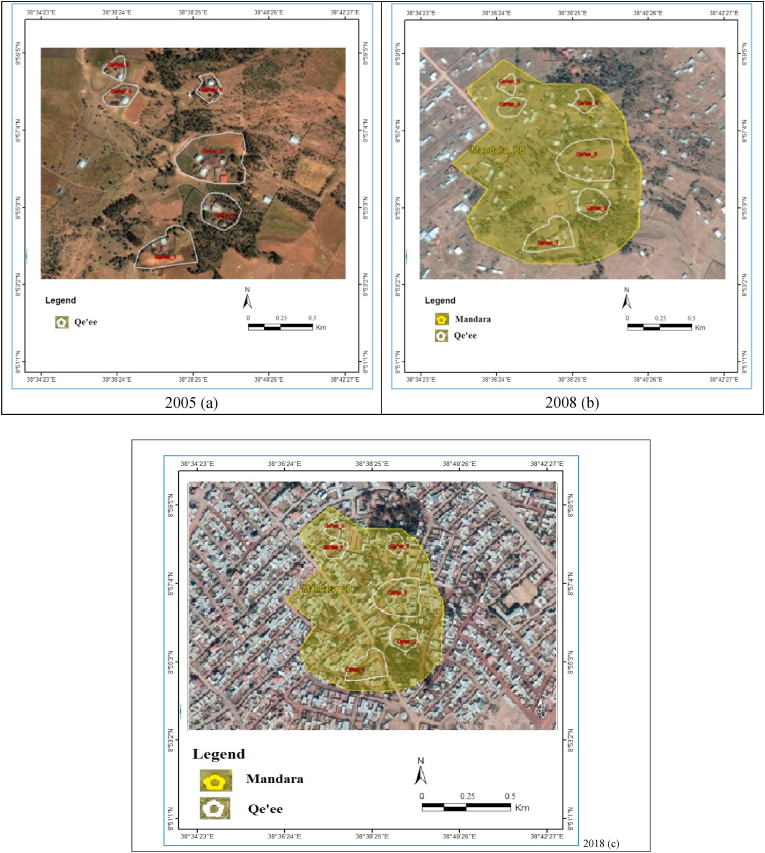

According to the interviewed elders and some urban historians, the traditional and consuetudinary rules in emergence of spontaneous development, and the process of settlement intensification operates as follows: the pioneer settlers, who mostly had land tenure rights in rural areas, built their residences on their land usually exist at segregate locations. As their families grew, farmer households tended to subdivide their land, primarily for their sons, who get married and usually live near their parents' homes. This rural neighborhood from the same family is called ‘Qe'ee’. When different Qe'ees get closer to each other, they become a ‘Mandara’. Predictably, a Mandara is not uniform, mostly conformed by people of different origins who have bought land around the pioneer settlements and settlement intensification process continues (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A typical Qe'ee (a) and Mandara (b) and spontaneously intensified settlements (c) in Sebeta town.

Non-availability of information on land ownership and associated resource and lack of available recorded data on the family members of pioneer settlers are the major handicaps for early distinctions of the pioneer settlements from later settlers, which in turn increased the transfer of land ownership right with false information (Document review, 2019; KII, 2020).

According to Dubbale D. et al., (2010), the indiscriminate growth is the main driver of slum development, which affects most of Ethiopia's urban areas. Similarly, Benti et al. (2021) stated spontaneous settlement growth due to limited attention given to pioneer settlements when building their social infrastructures lead to haphazard urban growth in Ethiopia.

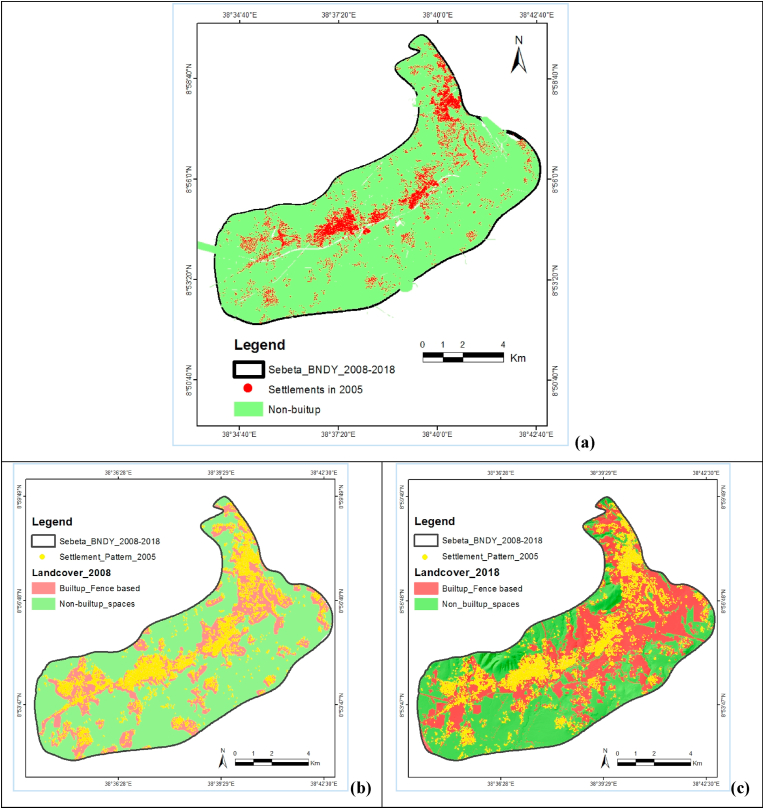

For instance, the major contribution of pioneer settlements and related spontanoues growth on spatial land cover changes and their consequences on planning have shown as follows: The 2005 point-based settlement map of the Sebeta town show the town had patchy, segregated and spontaneous settlement patterns, and development (Figure 6a). This indicate that such types of settlements had emerged prior to the 2008 first structure plan of the town. Three years later, in 2008, the segregated settlements were intensified and additional patches of settlements were formed (Figure 6b), and undoubtedly the 2008 structure plan of the town was prepared in presence of spontaneouly emerged settlements. Moreover, the 2018 land cover shows that the settlement coverage has increased in number and more intensified (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Settlement patterns and land cover changes of the Sebeta town in 2005, 2008 and 2018.

In general, the segregated points represent the majority of the pioneer settlements (‘Qe'ee’) while the patches represent settlement intensified and laterly joined communities of different ethnic backgrounds who owned land through various mechanisms of landownership (‘Mandara’).

The yellow spots in Figure 7 more clarify how urban settlements spontaneously emerge and intensify around the pioneer homesteads in a later phase. Therefore, the segregated pioneer settlements are determinants of an urban growth patterns and morphologies, and have consequences on planning.

Figure 7.

Settlements in 2005 (1a, 2a) and relative settlement growth patterns in 2018 (1b, 2b).

3.2.3. Pre plan availing socio-cultural services and physical infrastructures

Pre plan established socio-cultural services such as worshiping places, particularly Orthodox Tewahedo churches, local weekly markets, educational services and local administrative centers were also majorly contribute for the emergence of spontaneous settlements in the Sebeta town, specifically in the areas currently characterized as slum while physical infrastructures such as roads played a significant role in the expansion and intensification of such developments.

The first socio-economic service related drivers for the emergence of spontaneous settlement is the establishment of traditional weekly market area. The area was followed by settling retailer shops, small bars, and small factories, which led to the town's economic growth (OUPI, 2008). According to the information gathered from the local elders, the first constructions around the market were traditional mud huts, which offered merchants and market visitors homemade drinks such as 'Tella ' and ' Katikala '. These huts were built initially near the houses of pioneer settlers (‘Abbaa Lafaa’) and later in neighboring new settlements as land market and the demand for better facilities increased. This urbanization process was continued around the market area that is currently known as ‘Arat be Arat’ (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The map shows the locations of the local market of Sebeta, the first settlements in the so-called 'Arat be Arat ', and the subsequent intensification of the settlements illustrated on the 2005 Satellite image.

Figure 8 illustrates the patterns and intensification of the first and subsequent settlers around the market in 2005 (about 16 years of growth to now). This pattern is confirmed by observing the development of the footpaths, initially driven by rural residents on their way to the market and back to their homes, and then the gradual construction of roads linking the town center with neighboring rural Kebeles. Later, as it intensified along the streets from Addis Ababa to Jimma and Alemgena to Butajira, where settlements mushroomed after land traders offered farmland for housing (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Driving factors for the establishment of the Sebeta town and the emergence of spontaneous settlements (Illustrated based on the document review and historian interview, 2020).

The second social services that led to the consolidation of the town of Sebeta (Figure 9) were educational facilities, originally built to serve the first settlers in current Sebeta town and surrounding areas. The pioneer schools are the Mulugeta Gadle Primary school opened in 1950, the Sataba Merha Euran School founded in 1951 and which provided boarding schools to blind children from all over the country (OUPI, 2008; Local Elders, 2018; OUPI, 2018; Urban historian, 2018). The Sebeta High School, founded in 1968 (OUPI, 2008). Information compiled from the town elders indicate that due to the scarcity of high school at that time, it also served for students coming from very distant areas. This enforced students to rent houses around the school, which greatly encouraged the construction of rental houses in the surrounding and such construction contributed significantly to the intensification of spontaneous settlements in the area.

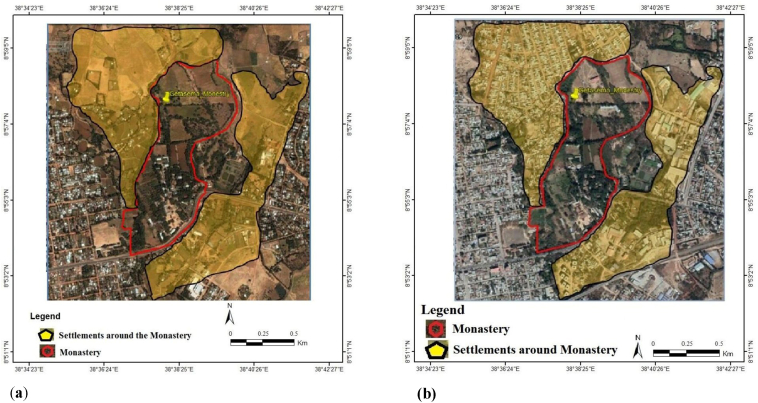

The third pole of attraction for the emergence of settlements to the region was the construction of the Sebeta Palace in 1942 by the emperor Haile Sellassie. In 1960 the emperor handed the palace to his wife Empress Menen AsfawShe then converted it into a monastery called Sebata Getsemany Betedenagel Tebabat. This event attracted several people from different regions of Ethiopia who had settled there (OUPI, 2008). The Palace is still serves as the Monastery. Besides a stream called ‘Burqaa Qeerroo’ originates from its compound and has been used as drinking water for the nearby settlements and some local elders argue that the presence of this stream also attracted people to settle around.

Although the Monastery area contributes to the town's establishment in attracting people to settle around, people were afraid to build their houses near it and take the site as sacred and a place of the Holy Spirit till the last decade. The limited development around the Monastery can be seen on the satellite image of 2008, the year when the first SP (2008–2018) of the town was prepared (Figure 10a). However, following this plan, which assigned all areas outside the Monastery to residential and other land uses, the built-up areas in surrounding increased (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Satellite images show settlements intensification layers around the former Palace (now Monastery) of Sebeta till 2008): Settlements were constructed far from the Monastery (a) In 2018: High settlement intensification around the Monastery (b).

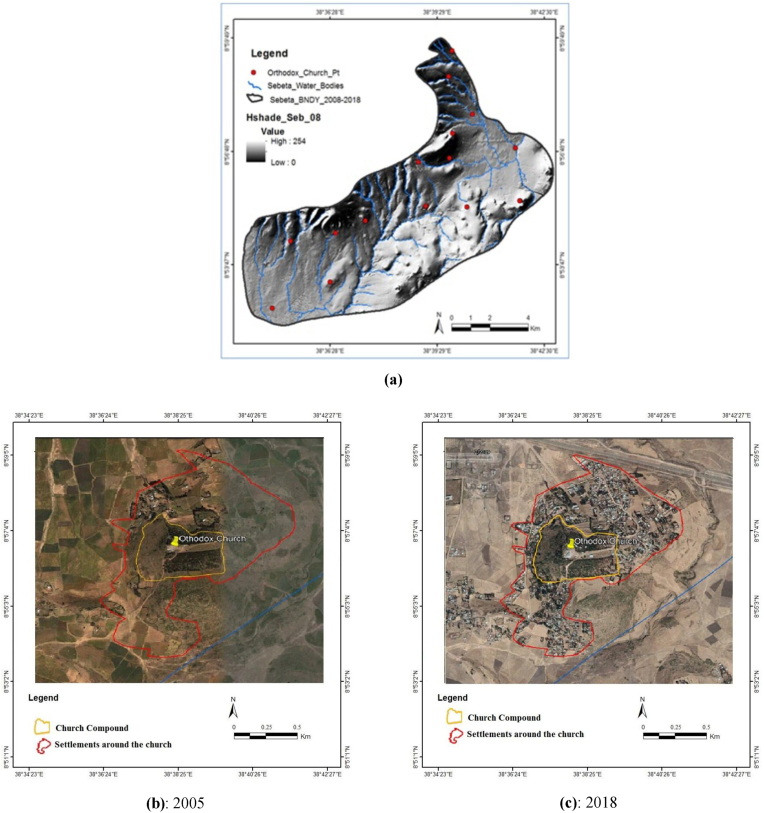

The fourth social service contributed significantly to the development of the spontaneous settlements in the town is Orthodox churches. In most cases, the churches were built on hilltops and near rivers (Figure 11a) in the absence of any settlements, but other worshiping places, such as Mosques and Protestant churches were mostly emerge after settlement consolidate and less contributed for the emergence of such settlements.

Figure 11.

Preferred location of Orthodox churches on hills and Rivers banks (a) and illustration showing how an Orthodox church derives and intensify settlements around its compound (b, c) in the Sebeta town.

In terms of land uses allocations, the urban planning in Ethiopia does not allow settlements on hilltops and nearby Rivers (MUDCo, 2012). In Addis Ababa for instance, it is mostly the river ecosystems, wetlands and highland areas that has fallen prey to informal activities. Such land parcels are usually associated with pockets of land that is lowly priced (Gondo, 2011). However, according to the church elders, the Orthodox churches usually prefer to establish on hilltops for the following major reasons: to make the church visible from afar and to prepare the devotee spiritually while hiking on the hills.

In fact, researches show that the churches have been protecting various vegetation and other natural elements within their compounds, but in terms of urbanization, it has attracted informal settlers and caused the depletion of the surrounding vegetation in the Sebeta town (Figure 11(b and c)).

A similar phenomenon is observed following the churches established on the riverbanks, which are also placed there for searching holy water for spiritual cleansing. In these cases, churches protect rivers from pollution. However, spontaneous and informal settlements tend to follow the establishment of churches and subsequently pollute the rivers with solid and liquid waste.

In addition to the identified hotspots that derived the inception of settlements in the Sebeta town, physical infrastructures like the Addis Ababa - Jimma main road crossing the Sebeta town, and the main road connecting Alemgena (Kebele 02 of Sebeta town) with Butajira (Figure 9) largely contributed for the intensification of settlements in the town. This finding comply with a research conducted by Meskerem et al. (2017) which proves proximity to existing road and other infrastructures like water and electricity were the priority driving factors when planning new settlements in Addis Ababa city in the Pre-1991 as those infrastructures had highly influenced the urban land use change of the city from its early stages development.

3.3. Consequences on the first structure plan of the Sebeta town

The traditional weekly market area which was served as the center for goods and product exchanges, educational facilities which was largely serving as a center of trained manpower, palace that served as the seat of government and center of command, Orthodox churches which have been serving as areas of worshiping for the large number of Ethiopian population were the main pull hotspots for the emergence of settlements in the Sebeta town.

In addition to the above social services related driving factors for the emergence of spontaneous settlements in the town, the physical infrastructures aggravated the intensification of settlements in the town. Incapable of early management of the driving factors for the genesis of spontaneous settlements contributed largely to the emergence of haphazard settlements (Figure 12a). These in turn led to the formation of slums like the settlements around the first local weekly market area of the town (Figure 12b).

Figure 12.

Settlements patterns and land use/cover of Sebeta town in 2008 (a) and a typical slum area in the built-up spaces around the Sebeta Market (b), which were used as the basis for the preparation of the 2008–2018 structure plan for the Sebeta town (c).

The areas are characterized with unorganized settlement patterns, unclear morphological aspects, dilapidated houses built with poor materials, and narrowed and bottlenecked access roads. Such slum characterized settlement patterns affected the plan making processes of the town as the areas forced urban planners to keep the irregularities to avoid the economic and social costs of demolishing houses and related infrastructures such as roads, waterlines, and electricity. Consequently, the first structure plan (2008–2018) of the town (Figure 12c), which was prepared in 2008, was based on such kinds of settlements that established before the plan, and the plan making process were affected negatively.

In addition, the newly emerging spontaneous urban developments following the driving factors will potentially show the character of the current slum areas existing in old and central areas of the town. The consequences of such development continue if appropriate planning measurements will not be considered.

The trend has stalled in the long run, creating the current slums in urban areas of the country that range from the capital city of Ethiopia to emerging towns like Sebeta.

3.4. Challenges ahead and implications

The findings show that unmanaged spontaneous urban development is a major factor for the formation of haphazard urban growth, which potentially lead to slum developments. In line with this, a previous study by Badmos et al. (2019) indicated as the factors for slum development are distance to markets, distance to shoreline, distance to local government administrative buildings and land prices. This research argues with these findings, but the identified factors are not the root causes for the initiation of slum development rather they are the facilitators for the expansion of the slums.

The situation of Sebeta town elicits the following challenges that planners should proactively consider for the town and other similar cases, mostly for urban areas in the developing countries as they are currently experiencing rapid urbanization trends. (i) Morphological and technical challenges: Formation of slum area is the character of unhealthy urban growth (Badmos et al., 2019). It prevents proper parcelation of the land and creates difficulties for an adequate layout of physical infrastructure such as roads, water, and sanitatary lines as well as increasing difficulty in integrating the natural and working landscapes in urban areas. Spontaneously developing settlements and informal land ownership are also the major causes for a segregated and chaotic urban development that contribute to the preparation of ineffective plans and inadequate implementation of the plans. (ii) Economical challenges: Unplanned urban growth also increases the costs of subsequent formalization processes. It can lead to an increase in the demolition of informal settlements that have higher compensation costs after the destruction. For example, the demolition and rehabilitation of settlements are often noticed during the implementation and construction of basic infrastructures, like widening of roads. All of these activities become an economic burden on society and governments. Most of these financial challenges arose during the implementation of plans like in the case study town, Sebeta. (iii) Social-ecological challenges: Haphazardly growing settlements tend to deplete natural and working landscapes as they arbitrarily occupy public spaces where they grow unplanned, resulting in unsanitary and overcrowded settlements. For example, the degradation of hilltop vegetation, the invasion of farmland and the pollution of the riverbanks like in the town of Sebeta.

4. Conclusion and outlook

Ethiopia has experienced the fastest rates of urbanization, and one of the major challenges of urban development in the country has been spontaneously emerging settlements, which have contributed to the country's increasing and unplanned urban growth trends, but spatial drivers for the spontaneity were overlooked. The presence of settlement patches in rural areas is the primary cause of this, and such trends usually intensify between the time an area receives urban entitlement and the preparation of its first formal plan centered on social-cultural services and physical infrastructures, hastening the haphazard urbanization process.

The social-cultural services are more prevalent at the inception of urbanization, typically forming patches of spontaneously emerging settlements. Physical infrastructures, on the other hand, drive patch connectivity and increase the intensity of the built up spaces, and determine the growth directions of urban areas.

Non-trace out and ineffective management of such spatial determinates eventually resulted in the country's haphazard urban growth. This is because non-early consideration of those drivers in the process of urban transformation incapacitates urban planners and forces them to plan on early slum areas, which further increases unplanned urban developments. The presence of the unplanned areas from their inception contributes to inner-city decay and is a major challenge to the sustainability of natural and working landscapes. As a result, integrative and early management of urban growth that focuses on these overlooked spatial drivers has the potential to reduce slum formations and improve urban sustainable development. Therefore, this paper proposes the use of a new urban planning approach that should begin at the Greenfield level in order to effectively identify the intrinsic values of natural and working landscapes that can be guided by land information systems for areas that help to plan based on the suitability of each land for the intended purpose.

This paper has contributed to a new body of global knowledge by demonstrating how traditional societal activities and ways of life of rural communities, the places where socio-cultural services such as worshiping areas, educational facilities, and traditional local markets are established play a significant role in the establishment and development of urban areas, as well as determining their growth patterns.

Therefore, this research paper has demonstrated, in terms of its implications for urban policies and planning that the curse of spontaneous urbanization process are the emergence of unexpected social and physical service factors. Underestimating and failing to recognize the triggering factors for the emergence of settlements has long-term consequences that are costly.

Dube (2013) who examined the challenges of land management in Arba Minch, an emerging regional town in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), suggested “Emerging towns need urgent planning approaches and management systems of urban land before things get out of control, as it is the case with the oldest urban centers of varying size in Ethiopia”. It is indicated in the introduction section of this research that the coverage of urbanized areas in the country is still small and most of them are at their early stages of development. Therefore, this research recommends a proactive urban management approach to control developments potentially emerge around the socio-cultural services and the development following physical infrastructures. As a result, proactive urban policies and planning measures help to alleviate the curse, because "prevention is better than cure."

Finally, because this study is more focused on spatial determinants, the authors recommend that future researchers can consider a detailed analysis of the country's social-economic related drivers of urbanization and combine it with the findings of this study. In addition, alternative approaches for spatial analysis using the combination of ERDAS IMAGINE, ENVI, GIS, R and other geospatial analysis and statistical software can be applied in the availability of other high-resolution satellite images rather than of Google Earth images. In the unlimited spatial data, spatial changes and Morphological characterization of settlements around the spatial drivers can be mapped and analyzed from the year when each drivers in place to the current spontaneity.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Solomon Benti: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Heyaw Terefe; Daniel Callo-Concha: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abou-korin A.A. Small-size urban settlements : proposed approach for managing urban future in developing countries of increasing technological capabilities , the case of Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2014;5(2):377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Alaci D.S.A. Regulating urbanisation in Sub-Saharan Africa through cluster settlements: lessons for urban mangers in Ethiopia. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2010;5(5):20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alem G. Urban plans and conflicting interests in sustainable cross-boundary land governance, the case of national urban and regional plans in Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2021;13(6) [Google Scholar]

- Andualem From Rural Town to Ethiopia’s Industrial Hub. 2019. https://newbusinessethiopia.com/nbe-blog/from-rural-town-to-ethiopias-industrial-hub/ Retrieved from.

- Antrop M. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2004. Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Arsiso B.K., Mengistu Tsidu G., Stoffberg G.H., Tadesse T. Influence of urbanization-driven land use/cover change on climate: the case of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Phys. Chem. Earth. 2018;105:212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele A., Tarekegn K. The impact of urbanization expansion on agricultural land in Ethiopia: a review. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2020;8(4) [Google Scholar]

- Babalola D.O. Vol. 2. 2012. Rural urban transformations in the developing countries; pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- Badmos O.S., Rienow A., Callo-Concha D., Greve K., Jürgens C. Simulating slum growth in Lagos: an integration of rule based and empirical based model. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019;77 [Google Scholar]

- Benti S., Terefe H., Callo-concha D. Challenges and prospects to sustain natural and working landscapes in the urban areas in Ethiopia. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustainabil. 2021;3 [Google Scholar]

- Burdett Matt. Characteristics of Urban Places – GeographyCaseStudy. 2018. https://geographycasestudysite.wordpress.com/characteristics-of-urban-places/ Retrieved from.

- Chaka S. Addis Ababa University; 2018. Impacts of Informal Settlement on Development of Sebeta City.http://213.55.95.56/bitstream/handle/123456789/15612/60. Shibru Chaka.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cherenet Z. 2015. DESIGNING the ‘ INFORMAL ’. Spatial Design Strategies for the Emerging Urbanization Around Water Bodies in Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. Urbanization in developing countries: current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technol. Soc. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- CSA . Addis Ababa.; 2013. Central Statistical Agency Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Wereda Level from 2014-2017. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; pp. 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- CSA-Ethiopia . Vol. 1. Addis Ababa . Ethiopia; 2007. 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Oromia Region. [Google Scholar]

- CSA-Ethiopia . 2017. The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Huang Z. Ecological and environmental effects of land use change in rapid urbanization: the case of hangzhou, China. Ecol. Indicat. 2017;81:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Dubbale D., et al. Urban environmental challenges in developing cities: the case of Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. Eng. Technol. 2010;4(6):397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Dube E.E. Urban planning & land management challenges in emerging towns of Ethiopia: the case of Arba Minch. J. Urban Environ. Eng. 2013;7(2):340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopian Agricultural Research Institute (EARI) No Title. 2009. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sebeta Retrieved June 4, 2021, from.

- Ethiopian Road Authority (ERA) Ethiopian Road and transport Bureau; 2001. Roads in the history. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell K. 1–19. 2017. The Rapid Urban Growth Triad : A New Conceptual Framework for Examining the Urban Transition in Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Fazal S. Urban expansion and loss of agricultural land - a GIS based study of Saharanpur City, India. Environ. Urbanization. 2000;12(2):133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fenta A.A., Yasuda H., Haregeweyn N., Belay A.S., Hadush Z., Gebremedhin M.A., Mekonnen G. The dynamics of urban expansion and land use/land cover changes using remote sensing and spatial metrics: the case of Mekelle city of northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Rem. Sens. 2017;38(14):4107–4129. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeyehu Admasu T. Urban land use dynamics, the nexus between land use pattern and its challenges: the case of Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia. Land Use Pol. 2015;45:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Giorghis Fasil. 2013. Issues Facing Addis Ababa and its Rapid Transformation. [Google Scholar]

- Girma A. South West Shewa Zone, Oromia Regional State; 2013. Urban Growth and Development in Ethiopia: a Case Study of Bantu Town. [Google Scholar]

- Girma Y., Terefe H., Pauleit S., Kindu M. Urban green spaces supply in rapidly urbanizing countries : the case of Sebeta Town, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Appl.: Soc. Environ. 2019;13:138–149. [Google Scholar]

- Gondo T. 2011. Linking non-urbanized areas and eco-sustainable planning : realities and Challenges from urban Ethiopia; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gutema Tesfaye. Addis Ababa University; 1997. Agricultural Land Use in Almgena Woreda, BA Senior Essay. [Google Scholar]

- Haregeweyn N., Fikadu G., Tsunekawa A., Tsubo M., Meshesha D.T. The dynamics of urban expansion and its impacts on land use/land cover change and smHaregeweyn. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2012;106(2):149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Harrower M.J., Andrea A.C.D. 2014. Landscapes of State Formation : Geospatial Analysis of Aksumite Settlement Patterns (Ethiopia) pp. 513–541. [Google Scholar]

- Heymans A., Breadsell J., Morrison G.M., Byrne J.J., Eon C. 2019. Ecological Urban Planning and Design : A Systematic Literature Review. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Du P., Guo D. Analysis of urban expansion and driving forces in xuzhou city based on remote sensing. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2007;17(2):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.S., Rana M.M.P., Ahmed R. Environmental perception during rapid population growth and urbanization: a case study of Dhaka city. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014;16(2):443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jenberu A.A., Admasu T.G. Urbanization and land use pattern in Arba Minch town, Ethiopia: driving forces and challenges. Geojournal. 2020;85(3) [Google Scholar]

- Kantakumar L.N., Kumar S., Schneider K. What drives urban growth in Pune? A logistic regression and relative importance analysis perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;60 [Google Scholar]

- Kindu M., Schneider T., Döllerer M., Teketay D., Knoke T. Scenario modelling of land use/land cover changes in Munessa-Shashemene landscape of the Ethiopian highlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroso N.H., Lengoiboni M., Zevenbergen J.A. Urbanization and urban land use efficiency: evidence from regional and Addis Ababa satellite cities, Ethiopia. Habitat Int. 2021;117 [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R.a., Casey M.a. Participants in a focus group. Focus Groups: A Pract. Guid. Appl. Res. 2009:63–84. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/24056_Chapter4.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kuddus M.A., Tynan E., McBryde E. Urbanization: a problem for the rich and the poor? Publ. Health Rev. 2020;41(1) doi: 10.1186/s40985-019-0116-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Chen D., Wu S., Zhou S., Wang T., Chen H. Spatio-temporal assessment of urbanization impacts on ecosystem services: case study of Nanjing City, China. Ecol. Indicat. 2016;71:416–427. [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Stringer L.C., Dallimer M. The spatial and temporal characteristics of urban heat island intensity: implications for east africa’s urban development. Climate. 2021;9(4) [Google Scholar]

- Lirebo D. 1–45. 2006. UDP-705 Housing In Urban Context. [Google Scholar]

- Mahiteme Y. 2007. Carrying the Burden of Long-Term Ineffective Urban Planning ’ an Overview of Addis Ababa’s Successive Master Plans and Their Implications on the Growth of the City. [Google Scholar]

- Meskerem Temporal dynamics of the driving factors of urban landscape change of Addis Ababa during the past three decades. Environ. Manag. 2017;56(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0953-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Urban Development and Construction (MUDCo) Addis Ababa; 2012. Structure Plan Manual (Revised Version) [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A., Worku H. Quantification of the land use/land cover dynamics and the degree of urban growth goodness for sustainable urban land use planning in Addis Ababa and the surrounding Oromia special zone. J. Urban Manag. 2019;8(1):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A., Worku H., Kindu M. Quantification and mapping of the spatial landscape pattern and its planning and management implications a case study in Addis Ababa and the surrounding area, Ethiopia. Geol. Ecol. Landscap. 2019:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- MUDCo . Addis Ababa; Ethiopia: 2010. Manual for the preparation and implementation of basic plans (structure plans) of small towns of Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- MUDCo, M. of U. D. and C. Sanitation and Beautification Bureau; 2012. Urban Planning , Sanitation and Beautification Bureau Urban Planning. [Google Scholar]

- National Labour Force Survey (NLFS) Inventory of Official National-Level Statistical Definitions for Rural/Urban Areas, 10. 2005. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/genericdocument/wcms_389373.pdf Retrieved from.

- OECD . Vol. 397. 2016. African Economic Outlook 2016. Sustainable Cities and Structural Transformation. [Google Scholar]

- Office for the Revision of Addis Ababa Master Plan (ORAAMP) Addis Ababa; Ethiopia: 2002. Development Plan of the City of Addis Ababa. [Google Scholar]

- Oromia Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise (OWWDSE) I. Addis Ababa; Ethiopia: 2011. Final Report Section III : Regional Planning. [Google Scholar]

- OUPI . 2008. Structural Plan Document of Sebeta Town. [Google Scholar]

- OUPI . 2018. Structural Plan Document of Sebeta Town. [Google Scholar]

- Sahle M., Saito O., Fürst C., Demissew S., Yeshitela K. Future land use management effects on ecosystem services under different scenarios in the Wabe River catchment of Gurage Mountain chain landscape, Ethiopia. Sustain. Sci. 2019;14(1):175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E., Kedir M. Urbanization and spatial connectivity in Ethiopia: urban growth analysis using GIS. 2009. http://essp.ifpri.info/publications/ ESSP II Working Paper, 3. Retrieved from.

- Sebeta city Sebeta City Administration Profile. 2019. http://www.sebetacity.com/index.php Retrieved August 22, 2019, from.

- Solomon Benti, Worku Hailu. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing; 2015. Impacts of Urban Sprawl on Environment: the Case of Sebeta, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene D., Kyriakopoulos G.L., Lekavicius V. Social Indicators Research. Vol. 158. Springer Netherlands; 2021. Energy poverty and low carbon just energy transition : comparative study in Lithuania and Greece. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Techniques G.I.S. 2017. Measuring and Mapping Urban Growth Patterns Using Remote Sensing and Measuring and Mapping Urban Growth Patterns Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrany M.S., Pradhan B. 2013. Remote Sensing Data Reveals Eco-Environmental Changes in Urban Areas of Klang Valley , Malaysia : Contribution from Object Based Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Terfa B.K., Chen N., Liu D., Zhang X., Niyogi D. 1–21. 2017. Urban Expansion in Ethiopia from 1987 to 2017 : Characteristics , Spatial Patterns , and Driving Forces. [Google Scholar]

- Terfa B.K., Chen N., Zhang X. Urbanization in small cities and their significant implications on landscape structures : the case in Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2020:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tian G., Jiang J., Yang Z., Zhang Y. The urban growth , size distribution and spatio-temporal dynamic pattern of the Yangtze River Delta megalopolitan region , China. Ecol. Model. 2011;222(3):865–878. [Google Scholar]

- Tola T.T., Khan A.Z., Wegayehu F. Urban Book Series. Springer Nature; 2021. Urban resilience and the question of food in Ethiopian urbanisation: the case of a small town in Ethiopia—amdework; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat What is urban resilience? 2022. https://urbanresiliencehub.org/what-is-urban-resilience/ Retrieved from.

- Oromia Urban Planning Institute (OUPI) Addis Ababa; 2010. Norms and Standards for Preparation, Monitoring and Evaluation of Implementation of Structure Plan. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group Urban Development Overview: Development News, Research, Data. 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview#1 Retrieved from.

- Wu J. Urban ecology and sustainability: the state-of-the-science and future directions. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2014;125:209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Young R. Landscapes of settlement: prehistory to the present. J. Rural Stud. 1999;15 [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Da L., Tang Z., Fang H., Song K., Fang J. Ecological consequences of rapid urban expansion: shanghai, China. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006;4(7):341–346. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.