Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Medicare Advantage (MA), Medicare’s managed care program, is quickly expanding, yet little is known about diabetes care quality delivered under MA compared with traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old enrolled in the Diabetes Collaborative Registry from 2014 to 2019 with type 2 diabetes treated with one or more antihyperglycemic therapies. Quality measures, cardiometabolic risk factor control, and antihyperglycemic prescription patterns were compared between Medicare plan groups, adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical factors.

RESULTS

Among 345,911 Medicare beneficiaries, 229,598 (66%) were enrolled in FFS and 116,313 (34%) in MA plans (for ≥1 month). MA beneficiaries were more likely to receive ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers for coronary artery disease, tobacco cessation counseling, and screening for retinopathy, foot care, and kidney disease (adjusted P ≤ 0.001 for all). MA beneficiaries had modestly but significantly higher systolic blood pressure (+0.2 mmHg), LDL cholesterol (+2.6 mg/dL), and HbA1c (+0.1%) (adjusted P < 0.01 for all). MA beneficiaries were independently less likely to receive glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (6.9% vs. 9.0%; adjusted odds ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.77–0.84) and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (5.4% vs. 6.7%; adjusted odds ratio 0.91, 95% CI 0.87–0.95). When integrating Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-linked data from 2014 to 2017 and more recent unlinked data from the Diabetes Collaborative Registry through 2019 (total N = 411,465), these therapeutic differences persisted, including among subgroups with established cardiovascular and kidney disease.

CONCLUSIONS

While MA plans enable greater access to preventive care, this may not translate to improved intermediate health outcomes. MA beneficiaries are also less likely to receive newer antihyperglycemic therapies with proven outcome benefits in high-risk individuals. Long-term health outcomes under various Medicare plans requires surveillance.

Introduction

Diabetes is reported in one in five Medicare beneficiaries aged ≥65 years and is associated with >60% higher out-of-pocket prescription expenditures compared with those without diabetes (1). With increasing costs and complexity of diabetes care, insurance structures may be strong determinants of the provision of and access and adherence to select therapies in clinical practice (2,3). Medicare Advantage (MA), the managed care alternative to traditional “fee-for-service” (FFS) Medicare, is growing rapidly and now provides health insurance coverage to nearly 40% of Medicare beneficiaries in the U.S. (4). As MA enrollment increases, so too have efforts to understand the association of MA with the quality of care received by patients with chronic diseases (5,6).

MA plans often leverage incentive structures to maintain care quality while limiting excessive health care utilization. Many MA plans provide broad access to supplemental benefits, such as telehealth services and transportation resources, not potentially available to traditional FFS Medicare, which may in turn theoretically improve care quality (7,8). However, since MA oversees total patient costs, these plans may also use various strategies to limit therapeutic expenditures and potentially introduce barriers to access to newer expensive therapies, including in diabetes management (9–11). On the other hand, MA plans may have longer-term incentives to use more expensive therapies if they can avoid more costly downstream care due to diabetes-related complications. Limited data are available examining how variations in Medicare plan designs may influence access, care quality, and prescription use, including of newer guideline-recommended therapies such as sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) for clinically high-risk patients, among individuals with diabetes in the U.S. Understanding these patterns is important given the rapid growth in MA enrollment over the last decade and ongoing policy debate about whether these plans result in the delivery of higher-value care, particularly for patients with chronic conditions.

The Diabetes Collaborative Registry (DCR) presents a unique opportunity to explore overall quality of care and use of antihyperglycemic therapies among patients with type 2 diabetes under MA versus FFS Medicare plans. Using this national registry, we sought to examine the association of MA versus FFS insurance status with 1) diabetes quality measures (e.g., appropriate screening and access to specialty care), 2) intermediate health outcomes (e.g., metabolic risk factor control), and 3) antihyperglycemic prescription patterns, including among high-risk individuals with established cardiovascular and kidney disease.

Research Design and Methods

Data Sources

The DCR is a U.S.-based outpatient quality improvement registry of >5,000 clinicians from 374 interdisciplinary practices, including 89 primary care, 275 cardiology, and 8 endocrinology clinics (12). As previously described, patient data, including demographics, clinical characteristics, vital signs, laboratory values, and medications, are collected through an automated system integration solution that extracts relevant data elements from electronic health records (13,14). These elements include discrete data fields, billing data, and physician notes. Data collection is standardized using established definitions, uniform data entry and transmission, and quality checks. In addition, rigorous back-end data quality checks are performed on the extracted data, and any data not meeting predefined statistical or clinical plausibility thresholds are quarantined from analyses and flagged for manual review and follow-up with individual practices (14).

Adults ≥65 years in the DCR were linked to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) claims data using the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File. We used these linked data sources to determine Medicare plan status, as described below. The Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri-Kansas City served as the data analysis center. Informed consent was not required given collection of usual care data, and Institutional Review Board approval was granted to analyze aggregate deidentified data for research by Chesapeake Research Review Inc. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

We identified all patients ≥65 years diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes (and not prediabetes or type 1 diabetes). To improve diagnostic accuracy of diabetes and given the focus on therapeutic use and access, we included those who were prescribed at least one antihyperglycemic therapy. For the primary analysis, from 2014 to 2017, we selected only patients with confirmed MA or FFS Medicare enrollment after linkage to the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File (Supplementary Fig. 1) (15). Consistent with prior work, patients enrolled in MA for at least 1 month were classified as MA patients (5). Of note, 92.9% of patients enrolled in MA for at least 1 month maintained that enrollment over the next 12 months. The remainder were considered FFS patients. Since Medicare linkage was not available for more recent years, in the secondary analysis, we evaluated treatment patterns through 2019 (relying on registry data alone for 2018 and 2019 to ascertain Medicare MA or FFS status). Among participants who were enrolled in FFS, 80% self-reported concordant enrollment in DCR registry data. Among participants who were enrolled in MA, only 54% self-reported concordant enrollment in DCR registry data. Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were collected at the last patient encounter.

Outcome Measures

We examined three sets of outcomes related to diabetes care: quality of care metrics, intermediate health outcomes, and antihyperglycemic prescription patterns using clinical and medication data available from the DCR only (Medicare prescription data were not available). Quality of care metrics included seven metrics as defined by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System, a Task Force that informs the clinical guidelines used to manage diabetes (16). These include 1) glycemic control within the past year (defined as patients ≤75 years with diabetes who had glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1c]) checked and ≤9.0%, 2) blood pressure (BP) control at most recent visit (defined as patients with hypertension who have a BP <140/90 mmHg or who have a BP ≥140/90 mmHg and were prescribed two or more antihypertensive medications), 3) receipt of a prescription for ACE inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in beneficiaries with coronary artery disease (CAD) at the most recent visit, 4–6) diabetic screening for nephropathy, retinopathy, and foot care within the past year, and 7) counseling for tobacco cessation within the previous 2 years. We examined intermediate outcomes, including systolic and diastolic BP, LDL cholesterol (LDL-c) concentration, and HbA1c level at the most recent visit. We used data from the most recent visit to examine receipt of a prescription for seven antihyperglycemic medication classes, including insulin, metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, GLP-1RAs, and SGLT2i, as described for use in diabetes treatment guidelines (17,18).

Statistical Analysis

We first compared differences in patient characteristics of Medicare enrollees with MA versus FFS using standardized differences (>10% difference considered clinically relevant). We then compared rates of achievement of quality metrics, intermediate outcomes, and individual antihyperglycemic classes between eligible patients enrolled in MA and FFS Medicare.

We used multivariable hierarchical logistic regression models with patient characteristics as fixed effects and practice sites as a random effect to account for correlation of patients within the same practice. For the continuous intermediate health measures, we used hierarchical linear regression models. For select evidence-based antihyperglycemic therapies (GLP-1RA and SGLT2i) that may more closely reflect care quality, we built multivariable hierarchical logistic regression models. All models were adjusted for patient-level demographic factors shown to be associated with diabetes care quality, including age, sex, and race and ethnicity (i.e., White or other), key medical comorbidities that may influence therapeutic decision making (i.e., atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease), median household income of ZIP Code (obtained from U.S. Census data from the 2018 American Community Survey) (19–21), number of antihyperglycemic therapies, and clinician-level factors (i.e., geographic region and clinical specialty). In addition, in sensitivity analyses, a second model was built adjusting for all patient- and clinician-level factors in the main model together with dual eligibility status. Dual Medicare and Medicaid eligibility was determined using CMS claims files, and both partial and full dual eligibility were counted. Dual eligibility was not available for 2014, and thus, this sensitivity analysis encompassed a smaller sample size (2015–2017) with complete covariate adjustment. Owing to failure of convergence and problematic parameterizations of certain models, we fit a mixed model by maximum likelihood with Laplace approximation using the PROC GLIMMIX command in SAS software (SAS Institute).

We finally evaluated trends in antihyperglycemic therapy use by Medicare MA versus FFS in high-risk clinical subsets, in which GLP-1RA or SGLT2i are recommended in current national and international clinical practice guidelines (17,22). In secondary analyses, we evaluated more recent trends in use of various antihyperglycemic therapies among Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in MA versus FFS plans, overall and among high-risk subsets. Since CMS claims data were not available for more recent years, we relied on investigator reported insurance status in the DCR registry alone to classify patients in 2018 and 2019.

All P values were 2-sided, and statistical significance was set at a P value <0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software. Data were analyzed from March 2020 to 1 April 2021.

Results

Clinical Profiles

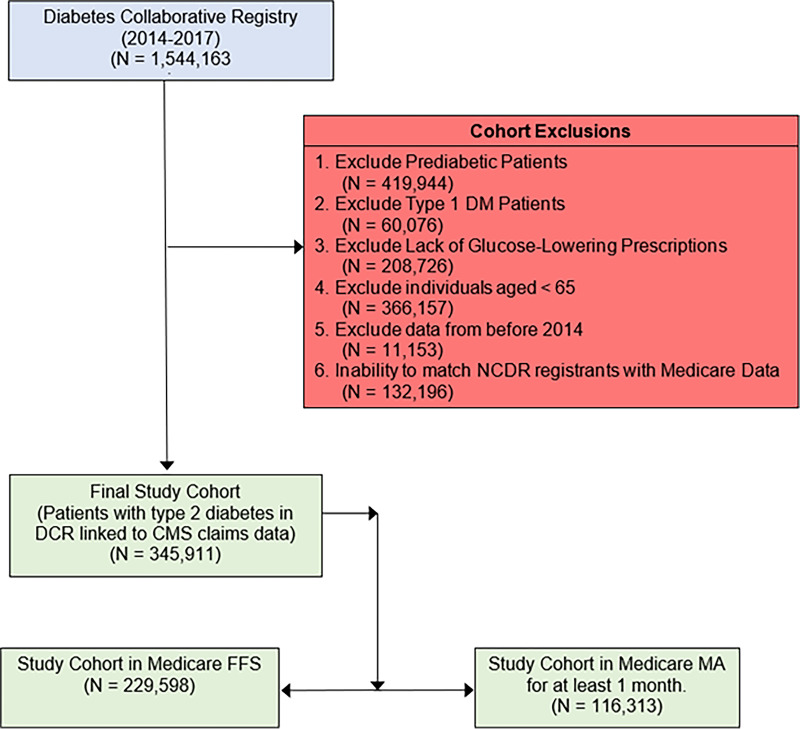

There were 478,107 patients with type 2 diabetes from January 2014 to December 2017 in the DCR registry treated with at least one antihyperglycemic therapy. Of these, 345,911 patients were linked to CMS claims data, including 116,313 (33.6%) enrolled in MA and 229,598 (66.4%) enrolled in FFS Medicare (Fig. 1). Medicare MA and FFS beneficiaries had similar age (74.6 ± 6.7 years vs. 74.7 ± 7.0 years) and proportions of women (50.4% vs. 46.1%); both standardized differences ≤10% (Table 1). MA enrollees were less likely to be White (80.5% vs. 87.8%), more likely to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (20.4% vs. 11.9%), and lived in areas of lower median income level ($52,700 vs. $56,200); all standardized differences >10%. MA beneficiaries were less likely to be treated by a cardiologist (41.2% vs. 44.7%) or endocrinologist (7.1% vs. 9.8%); both standardized differences >10%. On average, there were no substantial differences in the burden of clinical comorbidities between enrollees with MA and FFS. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in vital signs and laboratory values between MA and FFS beneficiaries (Fig. 2). Missing variables of key baseline characteristics are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Identification of study cohorts. We started with 1,544,163 individuals in the DCR, and after exclusions, our final study cohort was 345,911 Medicare beneficiaries, including 229,598 individuals in Medicare FFS and 116,313 individuals in MA. DM, diabetes mellitus; NCDR, National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

Table 1.

Clinical profiles in those enrolled in MA versus Medicare FFS

| Patient characteristics | MA (n = 116,313) | Medicare FFS (n = 229,598) | Standardized differencea (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 74.6 ± 6.7 | 74.7 ± 7.0 | 2.6 |

| Women | 58,658 (50.4) | 105,926 (46.1) | 8.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | 20.1 | ||

| White | 66,575 (80.5) | 146,662 (87.8) | |

| Other | 16,170 (19.5) | 20,419 (12.2) | |

| Household income (per $1,000) | 52.7 (43.4, 66.8) | 56.2 (46.3, 73.8) | 24.8 |

| Dual eligible status | 22,887 (20.4) | 26,131 (11.9) | 23.2 |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension | 105,138 (90.4) | 203,251 (88.5) | 6.1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 96,884 (83.3) | 189,036 (82.3) | 2.6 |

| Heart failure | 26,074 (22.4) | 48,829 (21.3) | 2.8 |

| CAD | 57,915 (49.8) | 118,399 (51.6) | 3.6 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23,375 (20.1) | 52,861 (23.0) | 7.1 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 28,828 (24.8) | 50,967 (22.2) | 6.1 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 24,710 (21.2) | 44,947 (19.6) | 4.1 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11,678 (10.0) | 21,513 (9.4) | 2.3 |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 72,521 (62.3) | 142,259 (62.0) | 0.8 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 1,411 (1.2) | 3,118 (1.4) | 1.3 |

| Depression | 14,226 (12.2) | 23,060 (10.0) | 7.0 |

| Infection–pulmonary | 7,445 (6.4) | 12,286 (5.4) | 4.5 |

| Tobacco use | 10.2 | ||

| Never | 48,771 (43.8) | 100,628 (45.6) | |

| Current | 34,644 (31.1) | 58,857 (26.7) | |

| Quit >12 months ago | 27,712 (24.9) | 60,833 (27.6) | |

| Lipid-lowering medications | |||

| Lipid-lowering nonstatin (any) | 37,594 (32.3) | 78,913 (34.4) | 6.4 |

| Ezetimibe | 8,088 (7.0) | 19,708 (8.6) | 6.8 |

| Fibrates | 12,122 (10.4) | 24,278 (10.6) | 2.4 |

| Niacin | 5,250 (4.5) | 10,832 (4.7) | 5.0 |

| Statin | 83,770 (72.0) | 162,041 (70.6) | 32.0 |

| PCSK9 Inhibitor | 358 (0.3) | 844 (0.4) | 1.0 |

| Lipid-lowering therapies, n | 3.2 | ||

| 0 | 22,582 (19.4) | 45,619 (19.9) | |

| 1 | 65,852 (56.6) | 126,451 (55.1) | |

| 2 | 27,738 (23.8) | 57,202 (24.9) | |

| 3 | 141 (0.1) | 326 (0.1) | |

| Antihypertensive medications | |||

| ACEi | 60,186 (51.7) | 106,795 (46.5) | 10.5 |

| ARB | 40,797 (35.1) | 80,053 (34.9) | 2.7 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 60,933 (52.4) | 114,145 (49.8) | 5.5 |

| β-Blocker | 74,161 (63.8) | 148,375 (64.6) | 3.0 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 2,772 (2.4) | 4,903 (2.1) | 2.3 |

| Loop diuretic | 36,220 (31.1) | 71,630 (31.2) | 4.4 |

| Antihypertensive therapies, n | 6.0 | ||

| 0 | 7,751 (6.7) | 18,047 (7.9) | |

| 1 | 31,126 (26.8) | 63,387 (27.6) | |

| 2 | 45,287 (38.9) | 88,654 (38.6) | |

| 3 | 25,534 (22.0) | 46,691 (20.3) | |

| 4 | 6,310 (5.4) | 12,303 (5.4) | |

| 5 | 305 (0.3) | 516 (0.2) | |

| Hospital /clinician characteristics | |||

| Geographic region | 9.3 | ||

| Northeast | 13,193 (11.3) | 31,897 (13.9) | |

| Midwest | 16,884 (14.5) | 35,016 (15.3) | |

| South | 74,279 (63.9) | 142,789 (62.2) | |

| West | 11,957 (10.3) | 19,896 (8.7) | |

| Clinical specialty | 17.0 | ||

| Cardiology | 47,912 (41.2) | 102,539 (44.7) | |

| Internal medicine | 22,462 (19.3) | 36,370 (15.9) | |

| Primary care | 23,493 (20.2) | 36,994 (16.1) | |

| Endocrinology | 8,306 (7.1) | 22,406 (9.8) | |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 143 (0.1) | 289 (0.1) | |

| Nephrology | 353 (0.3) | 944 (0.4) | |

| Other | 13,554 (11.7) | 29,869 (13.0) | |

| Objective measures | |||

| Vital signs | |||

| Weight (kg) | 86.5 (73.8, 101.2) | 88.2 (75.3, 102.7) | 6.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.5 (26.8, 35.1) | 30.6 (26.8, 35.1) | 0.5 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.0 (77.0, 102.0) | 90.0 (77.0, 102.0) | 0.5 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72.0 (65.0, 80.0) | 71.0 (64.0, 80.0) | 3.1 |

| Lipids | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 154.5 (132.0, 182.0) | 151.0 (128.3, 179.0) | 8.1 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 45.0 (37.0, 55.0) | 44.0 (37.0, 54.1) | 5.0 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 133.0 (97.0, 187.0) | 134.0 (97.0, 188.0) | 1.6 |

| Laboratory measures | |||

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 139.0 (117.0, 170.4) | 139.4 (117.5, 168.5) | 2.4 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) | 4.2 |

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 17.0 (8.0, 47.0) | 15.6 (7.4, 42.0) | 4.6 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 (12.0, 14.1) | 13.2 (12.1, 14.2) | 3.4 |

Data are presented as a mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range).

Standardized differences >10% are considered clinically relevant.

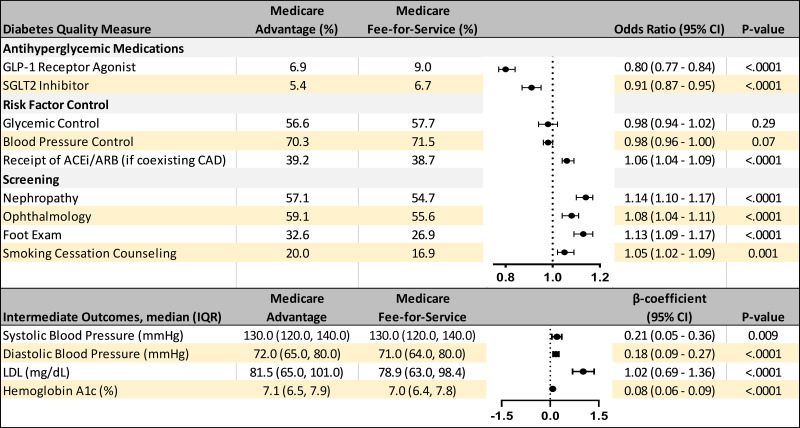

Figure 2.

Risk-adjusted associations of MA vs. Medicare FFS and diabetes care quality measures. We present risk-adjusted associations between Medicare plan type and quality measures, including GLP-1RAs and SGLT2i receipt, as well as risk factor control, receipt of ACEi or ARBs in beneficiaries with CAD, counseling for tobacco cessation, and screening for nephropathy, retinopathy, and foot care. Intermediate measures of HbA1c, BP, and LDL-c were also compared. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, median household income of ZIP Code, number of antihyperglycemic therapies, geographic region, and clinician specialty.

Diabetes Quality of Care Metrics and Intermediate Outcomes

No differences were observed in glycemic or BP control between MA and FFS Medicare beneficiaries (Fig. 2). MA beneficiaries were more likely than FFS Medicare enrollees to receive ACEi/ARBs for CAD (39.2% vs. 38.7%; adjusted odds ratio 1.06, 95% CI 1.04–1.09), tobacco cessation counseling (20.0% vs. 16.9%; adjusted odds ratio 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.09), and screening for retinopathy (59.1% vs. 55.6%; adjusted odds ratio 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.11), foot care (32.6% vs. 26.9%; adjusted odds ratio 1.13, 95% CI 1.09–1.17), and nephropathy (57.1% vs. 54.7%; adjusted odds ratio 1.14, 95% CI 1.10–1.17) (Fig. 2). MA beneficiaries had independently higher systolic BP (+0.2 mmHg), LDL-c (+2.6 mg/dL), and HbA1c (+0.1%) (P < 0.01 for all outcomes) (Fig. 2). Similar findings were observed when models were additionally adjusted for dual eligibility status for Medicare and Medicaid (Supplementary Fig. 1).

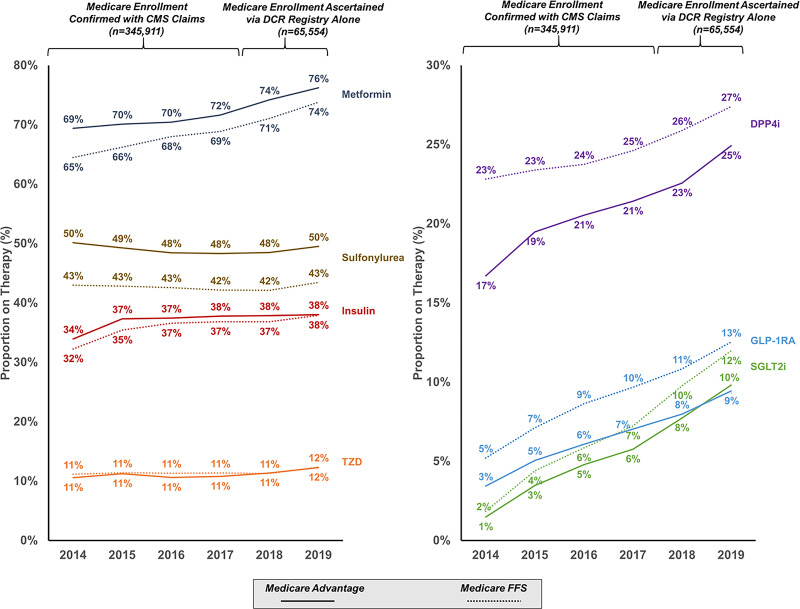

Antihyperglycemic Therapy Use

Compared with Medicare FFS beneficiaries, MA beneficiaries had higher relative use of metformin and sulfonylureas and lower use of DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1RAs, and SGLT2i (Fig. 3). After accounting for variable risk profiles, MA beneficiaries remained less likely to receive GLP-1RAs (6.9% vs. 9.0%; adjusted odds ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.77–0.84) and SGLT2 inhibitors (5.4% vs. 6.7%; adjusted odds ratio 0.91, 95% CI 0.87–0.95). When integrating CMS-linked data from 2014–2017 and more recent unlinked data from DCR through 2019 (total n = 411,465), differences in receipt of newer antihyperglycemic therapies persisted over time (Fig. 3). These differences also extended across high-risk clinical subgroups such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Trends in use of antihyperglycemic therapies over time. Enrollment status in MA or FFS was confirmed with CMS claims data for 2014–2017 and was obtained from investigator-reported DCR entries for 2018–2019.

Conclusions

In a contemporary national registry of older adults with type 2 diabetes, we observed notable differences in the quality of care delivered and drug treatment patterns for patients enrolled in MA compared with Medicare FFS. First, after accounting for differences in clinical profiles, patients enrolled in MA had higher rates of preventive care, including receipt of ACEi/ARBs for CAD, screening for retinopathy, foot care, and nephropathy, and tobacco cessation counseling. Despite this, MA beneficiaries had significantly higher BP, cholesterol, and glycemia, although the magnitude of these differences was modest. In addition, Medicare enrollees had overall low use of evidence-based antihyperglycemic therapies such as GLP-1RAs and SGLT2i, with MA beneficiaries significantly less likely to receive these agents, including those with high-risk comorbidities, such as established cardiovascular or kidney disease, in which these therapies are guideline recommended.

Managed Care Approaches to Diabetes Care

Prior studies have examined the association between Medicare plan structures and care patterns in conditions such as heart failure and CAD (5,6), but limited data exist in diabetes care. As a highly prevalent, chronic medical condition with established guideline-directed best practices as well as high therapeutic costs and health care utilization, type 2 diabetes is well-suited for potential managed care approaches. An older study using the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey found higher rates of health care utilization in Medicare FFS enrollees compared with those enrolled in MA, although with minimal differences in the process of diabetes care or care satisfaction (23). In our study, MA beneficiaries were more likely to achieve select quality measures, including screening and appropriate receipt of ACEi/ARBs. Together, these data suggest MA plans appear to be meeting key, generally lower-cost measures of quality compared with FFS Medicare plans.

Prescription Drug Therapy for Diabetes Under Medicare Plans

Our contemporary observations of differential medication use in MA versus Medicare FFS enrollees are congruent with prior assessments, including an analysis of MA beneficiaries compared with commercially insured enrollees that observed MA beneficiaries were less likely to initiate newer antihyperglycemic medications, including DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1RAs, and SGLT2i (24). The finding of differential prescribing of newer antihyperglycemic therapies among MA enrollees was also observed in an analysis of Medicare Part D claims from 2015 to 2016, which reported a 5 percentage point higher prescription rate in traditional Medicare beneficiaries compared with MA enrollees (25). These data are consistent with historical observations from Medicare data that reported higher use of established, mostly generic oral antihyperglycemic therapies in MA compared with stand-alone prescription drug plans (26).

Several potential explanations may underlie the observed differences in prescription drug use across Medicare plans. Under MA plans, utilization control mechanisms and cost containment strategies may steer clinicians and patients toward using lower-cost, generic therapies in diabetes care (27,28). At the clinician level, we observed differential access to specialty care (e.g., cardiologists and endocrinologists), with beneficiaries with MA plans reporting lesser access, which may in turn limit opportunities for care optimization with newer antihyperglycemic therapies among higher-risk subgroups. Furthermore, physicians who are more likely to prescribe high-cost antihyperglycemic therapies may be excluded from the coverage network, further impacting pharmacoequity (29). Whereas prior reports suggest that MA plans attract healthier individuals than FFS Medicare (30,31), MA enrollees in our study had greater social risk factors (i.e., greater dual eligibility and living in areas with lower median household incomes) compared with Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Even though risk-adjusted associations were largely unchanged after more detailed accounting of demographics and dual eligibility status, these data highlight the need to implement strategies for equitable access to evidence-based antihyperglycemic therapies (12). Moreover, a better understanding of the role of patient factors, such as cost-related nonadherence, intermittent prescription filling rates, and how clinical risk may influence preferential enrollment in one insurance program over the other, is warranted.

Promoting High Diabetes Care Quality Under Medicare Plans

Achieving high diabetes care quality, such as timely screening for microvascular complications and receipt of preventative therapies, are linked with fewer diabetes-related complications (32). Future work is needed to determine whether the mixed results we observed in improved preventive measures in MA compared with FFS Medicare beneficiaries but lower use of newer antihyperglycemic therapies ultimately results in differential long-term health outcomes for patients with diabetes. Similarly, surveillance of total health system costs is required. While our study did not evaluate health care expenditures, prior investigations have corroborated that Medicare FFS plans spend more per beneficiary on diabetes care, potentially related to increased observed short-term spending on higher-cost antihyperglycemic therapies (33). This observation may be expected, given the strong incentive for MA plans to control cost for their patients. However, assuring that these incentive structures in MA plans are evidence-based and promote intermediate and long-term health is a high priority. Indeed, despite these incentives, patients with diabetes enrolled in MA had slightly higher measures of blood pressure, lipids, and glycemia, suggesting that a better understanding is needed of the role of such incentives in this patient population (34,35).

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this analysis include its linkage to a detailed ambulatory care registry with administrative claims data, which simultaneously allows for understanding dimensions of diabetes care quality, laboratory-based risk factor control, and prescription therapies. Similarly, registry-based analyses allowed for assessment of treatment patterns in high-risk patient subsets that prior studies were unable to evaluate. Finally, while linked CMS claims data were only available through 2017, we confirmed similar therapeutic patterns in more contemporary data through 2019 with data ascertained in the DCR registry.

There are limitations of this study to note. First, the DCR is a voluntary registry, thus participating practices (and treated patients) may differ from those that do not join, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings.

Second, while the DCR is a detailed clinical registry, residual confounding may explain some differential therapeutic patterns in this analysis. Furthermore, there is potential for selection bias in our analysis, both due to actions of MA and FFS plans and the characteristics of individuals who chose to enroll in one or the other plan (36,37). While we conducted a robust risk-adjusted analysis, there may still be unmeasured differences between the patient populations we studied.

Third, MA plans may vary substantially in plan structures, but they were considered as a single entity in our analysis.

Fourth, we were able to examine median household income and insurance status, yet the DCR contains limited granular patient-level social determinants, such as a broader, disaggregated definition of race and ethnicity, employment status, or individual income level as well as limited clinician- and practice-level demographic characteristics, which may affect receipt of high-quality diabetes care (38,39).

Fifth, we were limited in our assessment of certain outcomes, including patient-reported outcomes measures, long-term diabetes complications, out-of-pocket and total expenditures, or health care utilization related to diabetes care. Similarly, we were not able to account for formulary status, patient preferences, or measures of frailty and functional status, which may influence therapeutic decision making. Additionally, we did not have data regarding medication dosing and adherence or sequencing of medical therapies (e.g., as first or second line) or use of advanced management techniques such as continuous glucose monitoring.

Sixth, follow-up HbA1c measurements were missing in many beneficiaries, which limited our assessment of glycemic control.

Seventh, our reliance on registry data to ascertain MA and FFS status for our secondary analyses was limited by lower self-report of enrollment status compared with CMS-derived data.

Finally, as with all observational studies, we can only report associations and do not prove a causal relationship between enrollment in MA or FFS and diabetes quality measures.

Conclusion

Leveraging data from >300,000 older adults with diabetes in a national outpatient registry, we found that those enrolled in MA had greater access to preventive care compared with Medicare FFS enrollees. However, MA beneficiaries had modestly but significantly poorer intermediate health outcomes and were less likely to be treated with newer, evidence-based antihyperglycemic therapies compared Medicare FFS beneficiaries. These therapeutic patterns extended to adults with established cardiovascular and kidney disease and persisted through 2019 after interval trials and guidelines affirmed their role in these settings. These data reinforce the need for surveillance of long-term outcomes under various Medicare plan structures and for program evaluation to ensure that indicated but more costly care is not stinted among at-risk beneficiaries under managed care approaches. Identifying strategies to ensure equitable access to high-quality diabetes care across population segments remains a high priority.

Article Information

Funding. U.R.E. has received grant support from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Division (CDA-20-049). J.F.F. has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR002542) and the Commonwealth Fund. R.P. reports support from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001424). R.K.W. reported receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant K23HL148525-1).

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Duality of Interest. The Diabetes Collaborative Registry (DCR) was formed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Diabetes Association, the American College of Physicians, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Joslin Diabetes Center, with funding support by AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. R.K.W. previously served as a consultant for Regeneron. B.R.D. reports grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Relypsa, Novartis, and SC Pharmaceuticals. M.N.K. reports grant/research support from Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca, honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Novo Nordisk, and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck (Diabetes), Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Vifor Pharma. M.V. has received research grant support or served on advisory boards for American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Baxter Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pharmacosmos, Relypsa, Roche Diagnostics, and Sanofi, speaker engagements with Novartis and Roche Diagnostics, and participates on clinical trial committees for studies sponsored by Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. U.R.E. and T.M.A.L. wrote the manuscript. Y.T., F.T., and P.G.J. performed statistical analyses. M.V. supervised the work. U.R.E., Y.T, J.F.F., T.M.A.L., F.T., P.G.J., R.P., R.K.W., N.R.D., S.N.M., M.N.K., and M.V. contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. M.V. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented as an oral presentation and selected for a Young Investigator Award at the 81st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, virtual meeting, 25–29 June 2021.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.19660854.

References

- 1. Hasche J, Ward C, Schluterman N. Diabetes Occurrence, Costs, and Access to Care among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years and Over. In Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Office of Enterprise Data & Analytics, 2017. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/Downloads/Diabetes_DataBrief_2017.pdf

- 2. Herkert D, Vijayakumar P, Luo J, et al. Cost-related insulin underuse among patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:112–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou X, Shrestha SS, Shao H, Zhang P. Factors contributing to the rising national cost of glucose-lowering medicines for diabetes during 2005-2007 and 2015-2017. Diabetes Care 2020;43:2396–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freed M, Damico A, Neuman T. A Dozen Facts about Medicare Advantage in 2020. Kaiser Family Foundation; 13 January 2021. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-dozen-facts-about-medicare-advantage-in-2020/

- 5. Figueroa JF, Blumenthal DM, Feyman Y, et al. Differences in management of coronary artery disease in patients with Medicare Advantage vs traditional fee-for-service Medicare among cardiology practices. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:265–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Frakt AB, et al. Quality of care and outcomes among Medicare Advantage vs fee-for-service Medicare patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1349–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kornfield T, Kazan M, Frieder M, Duddy-Tenbrunsel R, Donthi S, Fix A. Medicare Advantage Plans Offering Expanded Supplemental Benefits: A Look at Availability and Enrollment. The Commonwealth Fund, 10 February 2021. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/feb/medicare-advantage-plans-supplemental-benefits

- 8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . CMS finalizes policies to bring innovative telehealth benefit to Medicare Advantage. 5 April 2019. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-finalizes-policies-bring-innovative-telehealth-benefit-medicare-advantage

- 9. Slabaugh SL, Xu Y, Stacy JN, et al. Antidiabetic treatment patterns in a Medicare Advantage population in the United States. Drugs Aging 2015;32:169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costantino ME, Stacy JN, Song F, Xu Y, Bouchard JR. The burden of diabetes mellitus for Medicare beneficiaries. Popul Health Manag 2014;17:272–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosenzweig JL, Taitel MS, Norman GK, Moore TJ, Turenne W, Tang P. Diabetes disease management in Medicare Advantage reduces hospitalizations and costs. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:e157–e162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arnold SV, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Lam CSP, et al.; Insights from the Diabetes Collaborative Registry (DCR) . Patterns of glucose-lowering medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes and heart failure. Am Heart J 2018;203:25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arnold SV, Inzucchi SE, McGuire DK, et al. Evaluating the quality of comprehensive cardiometabolic care for patients with type 2 diabetes in the U.S.: the Diabetes Collaborative Registry. Diabetes Care 2016;39:e99–e101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arnold SV, Goyal A, Inzucchi SE, et al. Quality of care of the initial patient cohort of the Diabetes Collaborative Registry®. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brennan JM, Peterson ED, Messenger JC, et al.; Duke Clinical Research Institute DEcIDE Team . Linking the National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry with Medicare claims data: validation of a longitudinal cohort of elderly patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diabetes Collaborative Registry Program Measures & Metrics . Diabetes Collaborative Registry, 2020. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://veradigm.com/img/diabetes-registry-program-metrics-2021.pdf

- 17. Doyle-Delgado K, Chamberlain JJ, Shubrook JH, Skolnik N, Trujillo J. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment of type 2 diabetes: synopsis of the 2020 American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:813–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Diabetes Association . 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl. 1):S98–S110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. United States Census Bureau . 2018 Median Household Income in the United States, 2019. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2018-median-household-income.html

- 20. Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res 2015;50:398–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liberatos P, Link BG, Kelsey JL. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev 1988;10:87–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:5–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park S, Larson EB, Fishman P, White L, Coe NB. Differences in health care utilization, process of diabetes care, care satisfaction, and health status in patients with diabetes in Medicare Advantage versus traditional Medicare. Med Care 2020;58:1004–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Deng Y, et al. Comparison of diabetes medications used by adults with commercial insurance vs Medicare Advantage, 2016 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2035792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Souza J, Ayanian JZ. Use of diabetes medications in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Am J Manag Care 2021;27:e80–e88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erten MZ, Stuart B, Davidoff AJ, Shoemaker JS, Bryant-Comstock L, Shenolikar R. How does drug treatment for diabetes compare between Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MAPDs) and stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs)? Health Serv Res 2013;48:1057–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Less intense postacute care, better outcomes for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than those in fee-for-service. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:91–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bergeson JG, Worley K, Louder A, Ward M, Graham J. Retrospective database analysis of the impact of prior authorization for type 2 diabetes medications on health care costs in a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plan population. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:374–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jacobson G, Rae M, Neuman T, Orgera K, Boccuti C. Medicare Advantage: How Robust Are Plans’ Physician Networks? The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017. Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicare-Advantage-How-Robust-Are-Plans-Physician-Networks

- 30. Morgan RO, Virnig BA, DeVito CA, Persily NA. The Medicare-HMO revolving door--the healthy go in and the sick go out. N Engl J Med 1997;337:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . Improving risk adjustment in the Medicare program. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, 2014, p. 19-36 Accessed 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/jun14_entirereport.pdf

- 32. Saundankar V, Ellis J, Moretz C, et al. A historical retrospective analysis of the impact of diabetes quality measure attainment on outcomes in Medicare Advantage members. Popul Health Manag 2017;20:146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders R, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP, Ayanian JZ. A comparison of relative resource use and quality in Medicare Advantage health plans versus traditional Medicare. Am J Manag Care 2015;21:559–566 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T, Gold M. Medicare Advantage 2015 Data Spotlight: Overview of Plan Changes. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014. Accessed 1 April 2022. Available from https://files.kff.org/attachment/data-spotlight-medicare-advantage-2015-data-spotlight-overview-of-plan-changes

- 35. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . 2017 Star Ratings. 12 October 2016. Accessed 1 April 2022. Available from https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2017-star-ratings

- 36. Johnston KJ, Hammond G, Meyers DJ, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of race and ethnicity and Medicare program type with ambulatory care access and quality measures. JAMA 2021;326:628–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Growth in Medicare Advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40:945–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM. Racial and ethnic disparities among enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2288–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rivera-Hernandez M, Leyva B, Keohane LM, Trivedi AN. Quality of care for white and Hispanic Medicare Advantage enrollees in the United States and Puerto Rico. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:787–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]