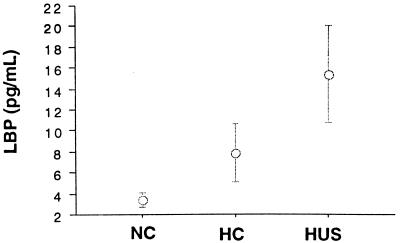

We report double-determinant sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measurements (4) of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding protein (LBP) in children with uncomplicated Escherichia coli O157:H7 hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and those with O157:H7-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Characteristics of these children have been previously reported (5). The analytical sensitivity of LBP measurement was 1 ng/ml, and assay precision was 14%. Figure 1 shows that elevated levels of LBP in plasma were noted for children with O157:H7 infections (HC versus normal controls, P < 0.0001) and that concentrations were increased twofold among those who developed HUS (uncomplicated HC versus HUS, P < 0.005). Levels of circulating LPB in HUS were comparable to those preivously noted for patients with inflammatory bowel disease and approximately half those of patients with sepsis (1). In our population, LBP measurements were not correlated to the leukocyte count, interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8, or soluble L-, E-, or P-selectin but were significantly correlated with levels of IL-10 (r = 0.6, P < 0.0008), IL-1 receptor antagonist (r = 0.6; P < 0.0005), and soluble intercellular adhesion molecular 1 (ICAM) (R = 0.4; P < 0.02).

FIG. 1.

—Circulating LBP concentrations in E. coli O157:H7 infections (mean ± 95% confidence intervals [CI]). LBP levels in plasma among 10 normal controls (NC), 15 children with uncomplicated HC, and 10 children with HUS. Subjects were matched for the time interval elapsed between onset of enteritis and blood sample collection (6.5 ± 3.3 versus 6.8 ± 3.8 days, respectively [not a significant difference]). Twofold-increased LBP concentrations were noted for children with HUS compared to those with uncomplicated HC (P < 0.005 [Mann-Whitney U test]). Among 9 children with uncomplicated HC, serial LBP measurements were as follows (means ± 95% CI): first sample, 8.7 ± 6.2 pg’ml; second sample, 4.0 ± 3.4 pg/ml (P <MEASUREME0.01). LBP concentrations remained lower than those among children with HUS (P < 0.009).

LBP is a 60-kDa acute-phase response protein synthesized by hepatocytes which potentiates the LPS-induced stimulation of CD14+ cells such as macrophages and neutrophils; LBP may also activate CD14− epithelial or endothelial cells through the binding with soluble CD14 (6). Secretion of cytokines and adhesion molecules induced by LPS results in neutrophil activation. Interestingly, we detected an association between circulating LBP levels and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and IL-1 receptor antagonist) which are classically produced by macrophages (5).

Circulating endotoxin immune complexes have been demonstrated in HUS due to shigellosis only (3). Nevertheless, the involvement of LPS in the pathophysiology of verotoxigenic E. coli infections has been hypothesized (2). Our data indicate that the acute-phase response to LPS is associated with the severity of illness during O157:H7 infections. It remains to be determined if the amount of bacterial inoculum or the effect of renal reabsorption of LBP may account for the increased levels noted during HUS. However, only one child received antibiotic therapy before blood sample collection. Consequently, our data should not have been affected by this parameter. Further studies are needed to determine the role of endotoxin in the pathophysiology of E. coli O157:H7 infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caroll S F, Dedrick R L, White M L. Plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide binding protein correlate with outcome in sepsis and other patients. Shock. 1997;8:101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karpman D, connell H, Svensson M, Scheutz A, Alm P, Svanborg The role of lipopolysaccharides and Shiga-like toxin in a model of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:611–620. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koster F, Levin J, Walker L, Tung K S K, Gilman R H, Rahaman M M, Majid M A, Islam S, Williams R C. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome after shigellosis. Relation to endotoxemia and circulating immune complexes. N Engl J Med. 1979;298:927–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197804272981702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meszaros K, Aberle S, White M, Parent J B. Immunoreactivity and bioactivity of lipopolysaqccharide-binding protein in normal and heat-inactivated sera. Infect Immun. 1995;63:363–365. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.363-365.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Proulx F, Litalien C, Turgeon J P, Mariscalco M M, Seidman E. Inflammatory mediators in hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Inf dis J. 1998;17:899–904. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199810000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Write S D. CD14 and immune response to lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1991;252:1321–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1718034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]